Two

THE DUNBAR HOTEL

When the steeple bell says, ‘Goodnight, sleep well’

We’ll thank the small hotel

We’ll creep into our little shell

And we will thank the small hotel together.

—Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, composers

“There’s a Small Hotel”

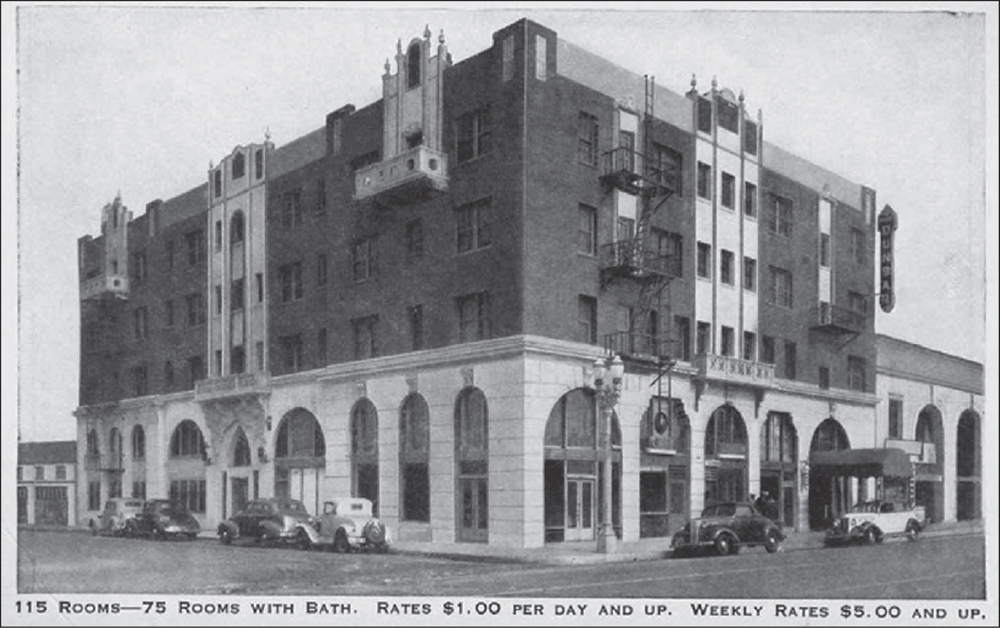

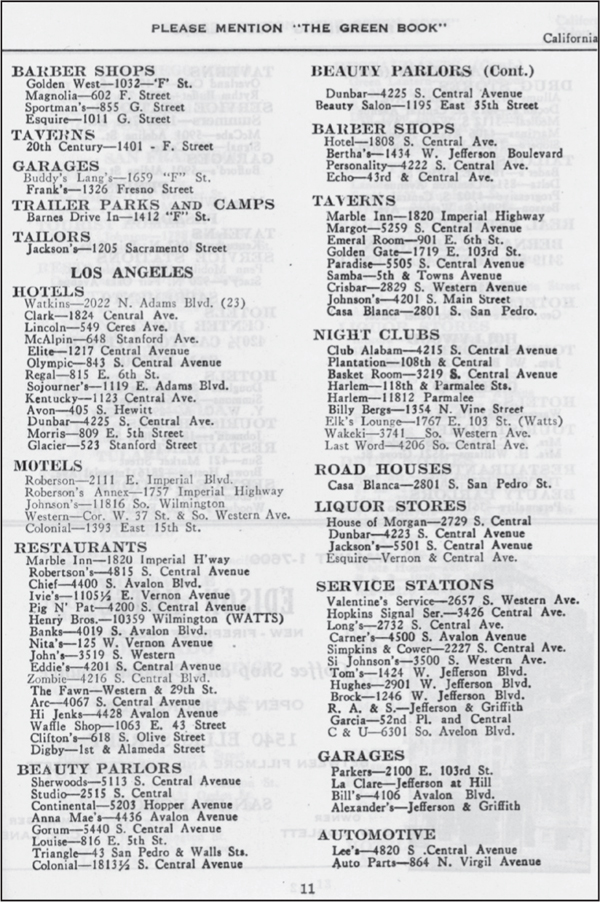

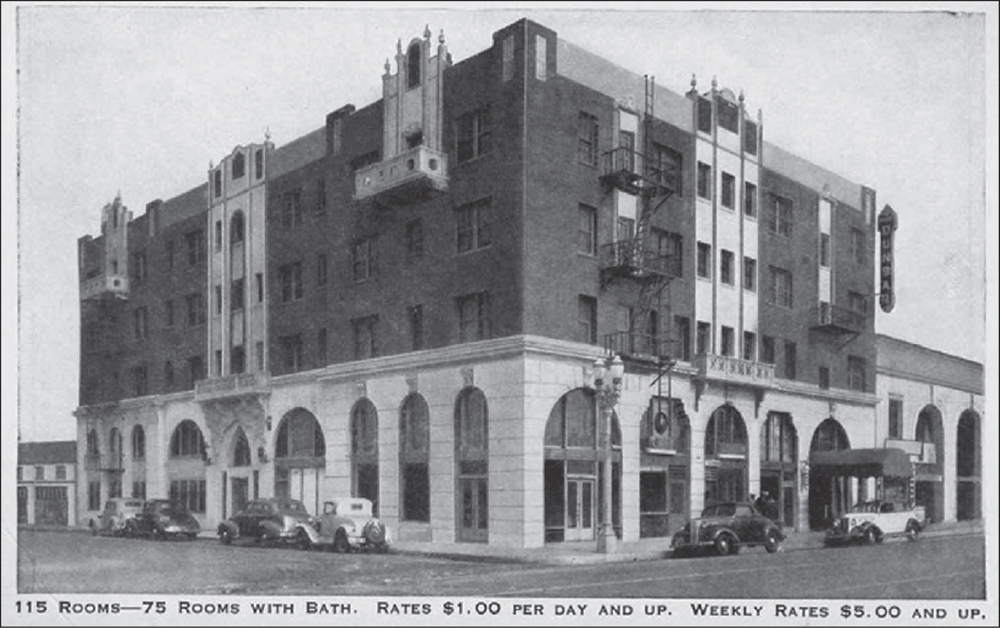

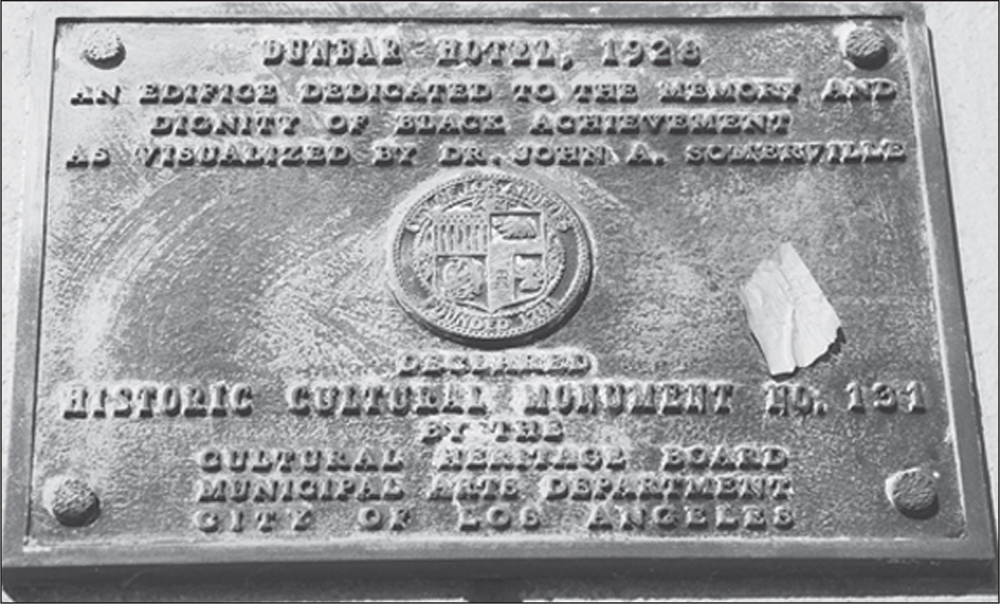

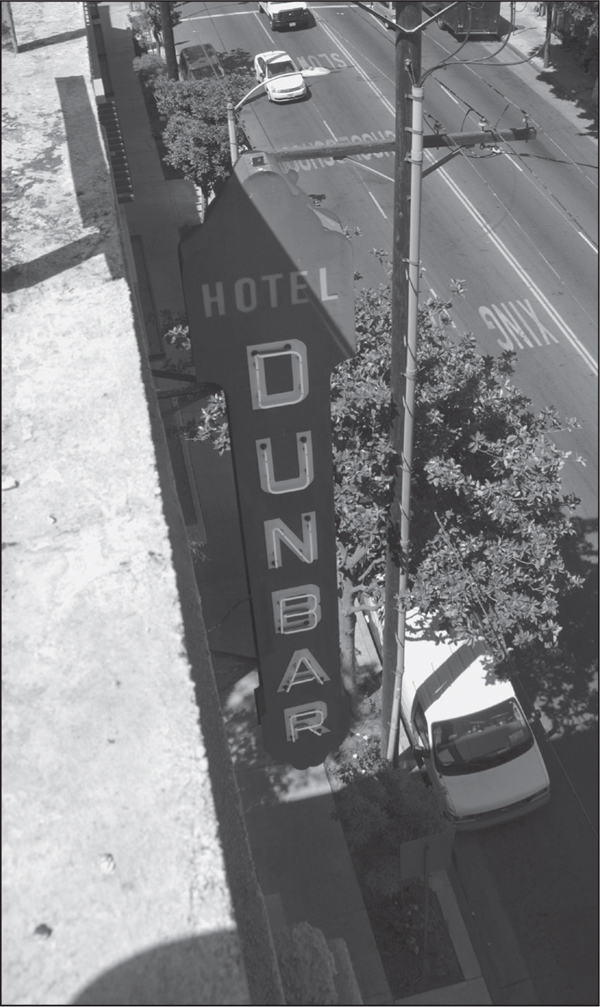

From the roof of the Dunbar Hotel, there is still an unobstructed 360-degree view of Los Angeles’s suburban sprawl. The five-story structure was built as the Hotel Somerville in 1928, the same year the City of Los Angeles completed its 32-story city hall (located 3.5 miles directly north in downtown). Located on the corner of Forty-second Place and South Central Avenue, the Dunbar Hotel changed owners and names in 1930. It quickly became the centerpiece of the Central Avenue scene, offering accommodations to out-of-towners while providing a beauty parlor, liquor store, messaging services, and a few communal spaces equipped with a bar and a bandstand. Well into the 1950s, a large number of Los Angeles hotels were segregated. Finding luxurious accommodations for African Americans was fairly limited; however, the Dunbar served as a jazz embassy for the road weary, welcoming swinging dignitaries with the warm reception they richly deserved.

The high-ceilinged lobby of the Hotel Somerville, located at 4225 South Central Avenue, seemed to have a piano tucked into every corner. Entertainment and leisure were the goals of the Somerville, and they were abundant. An advertising board on the mezzanine highlights an appearance by Alton Redd and his Tivoli Theater band, named after a venue located further down at 4319 Central Avenue. Delicate Spanish-style frescoes were painted above the lobby and light streamed in from the courtyard off East Forty-second Place, which provided ample space to sit and read while planning a night’s adventure. (Both, courtesy of the Quincy Inara Music Collection.)

Despite the hotel’s name change in 1930, the ghosts of the Somerville are still stamped into the entrance of the Dunbar Hotel today. The cracked slab sits on the sidewalk of Central Avenue in the middle of the structure. Imagine the many cigarette butts and shoe styles this sturdy floor mat has experienced from the hundreds of thousands of pairs to grace its entryway.

The Dunbar Hotel (not yet surrounded by giant trees in this photograph) boasted 115 rooms across five floors. While daily rates offered a break for those just passing through, weekly rates catered to artists and musicians looking to spend an extended stay on the avenue. (Courtesy of the Quincy Inara Music Collection.)

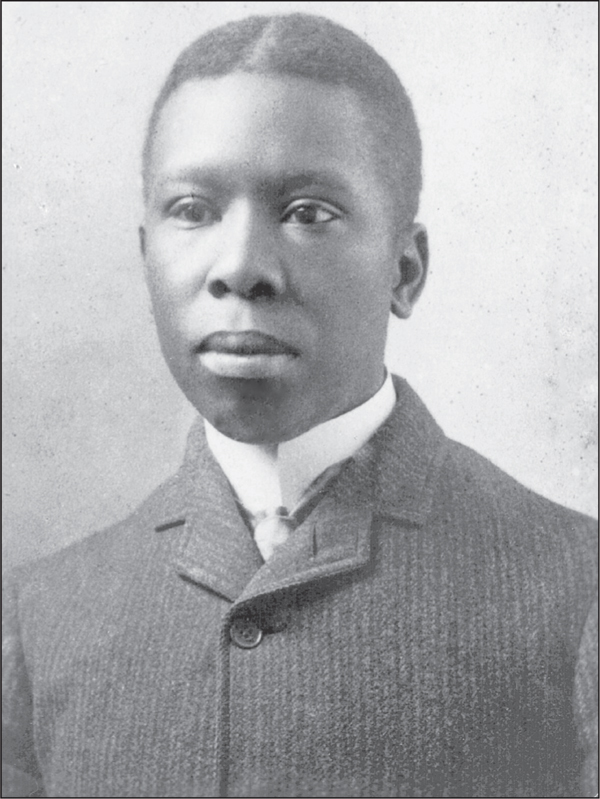

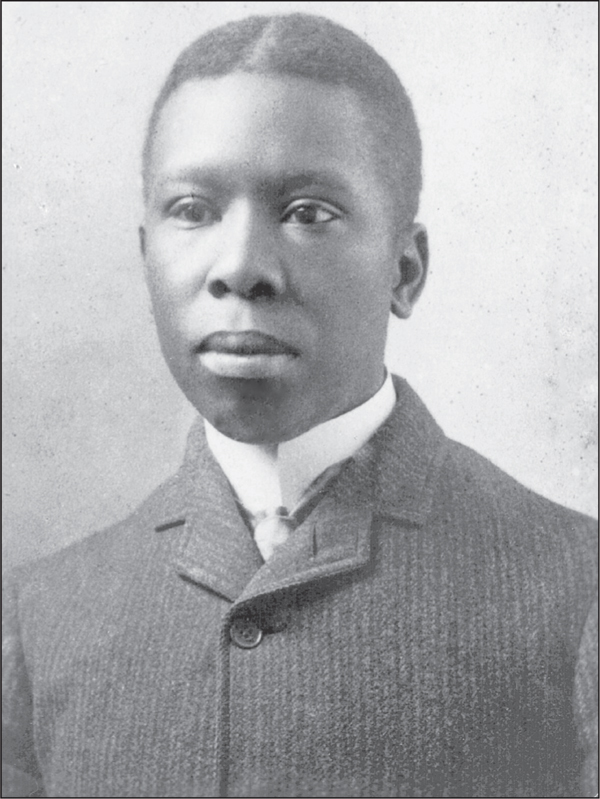

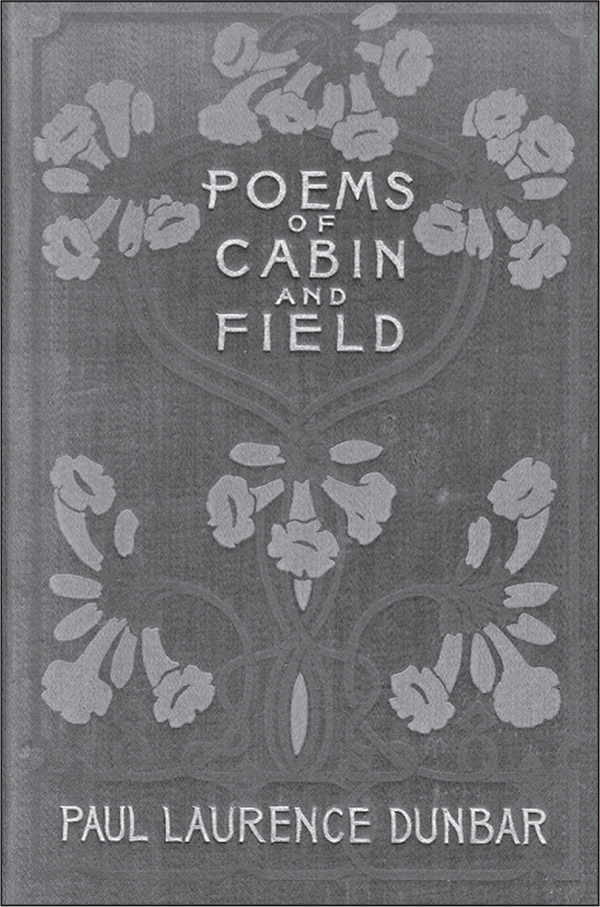

Paul Laurence Dunbar only lived to the age of 33 before succumbing to tuberculosis. He likely never visited California and would not have seen the Dunbar Hotel if he had; he died 24 years before it was dedicated to him. He was a poet, novelist, and playwright with close ties to the Wright brothers in his native Ohio. The title of Maya Angelou’s autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, immortalized one of Dunbar’s most enduring stanzas: “I know why the caged bird sings, ah me, / When his wing is bruised and his bosom sore– / When he beats his bars and he would be free; / It is not a carol of joy or glee, / But a prayer that he sends from his heart’s deep core, / But a plea that upward to Heaven he flings– / I know why the caged bird sings!”

Architect Steven Fader had the daunting task of restoring the Dunbar Hotel. It had fallen into disrepair before a group took over the facility and helped to turn it into a senior and low-income housing community. Comparisons to photographs from 85 years prior show just how exact the result is: the frescoes and light fixtures are restored, a piano cries for attention in the corner, and the same light streams in from above.

The lush outdoor courtyard has immaculate tile work with a bubbling fountain wrapped in Spanish tile. The skylights above keep the area bright while the plant life keeps things cool. A small balcony on the second floor opens onto the small public space. The next project is to fill the vacant corner of the building with a restaurant, thereby finally restoring the entire complex to its former glory.

Aside from the four-story tree towering above Central Avenue, not much has changed on the outside of the Dunbar Hotel. The car models have changed and the streetcar no longer rattles the windows; otherwise, the building is immaculately preserved.

Segregated businesses in Los Angeles made it extremely difficult for many to find a place where they could be comfortable. No matter how much money or respectability a person might have had, they were frequently turned away from the Hollywood hotels. Thus, the guest list at the Dunbar Hotel was an astounding collection of who’s who in the entertainment world. (Photograph by William Gottlieb.)

Vocalist Billie Holiday (above) was a regular guest and bandleader Cab Calloway (right) often hung his zoot suits in one of the 115 closets available. In order to catch a glimpse (and maybe a little career advice), young musicians would wait out front when they knew someone famous was in town. (Photograph by William Gottlieb.)

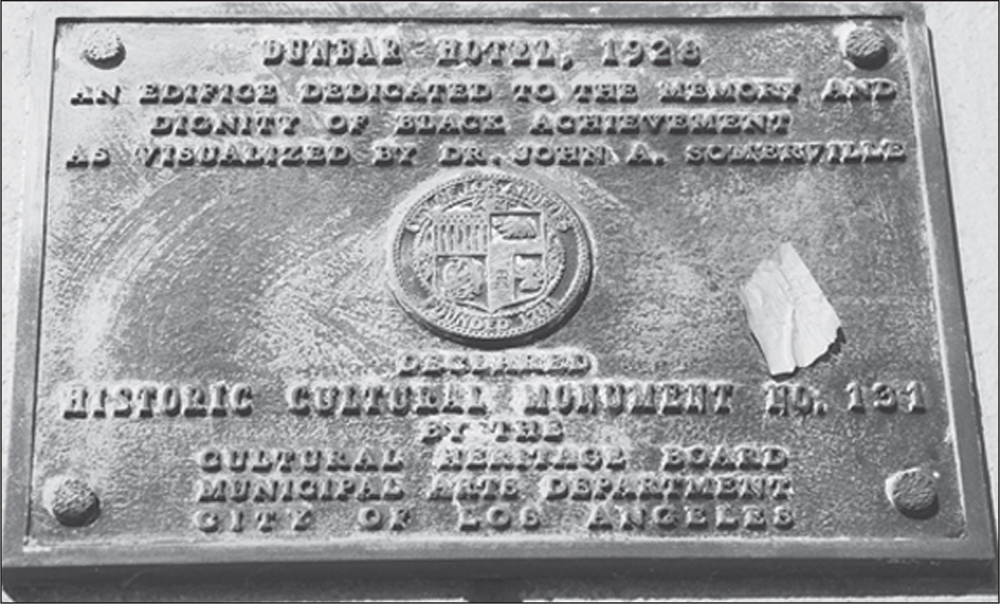

The Dunbar Hotel was placed in the National Register of Historic Places in January 1976. The building had become apartments after having been vacant for 13 years, suffering from neglect and vandalism. Owner Bernard Johnson briefly opened a museum of black culture in 1990, but the building was foreclosed on 18 years later. The project has seen a more promising rebuild in 2013, with a long-term plan for its rightful place in Los Angeles’s African American history.

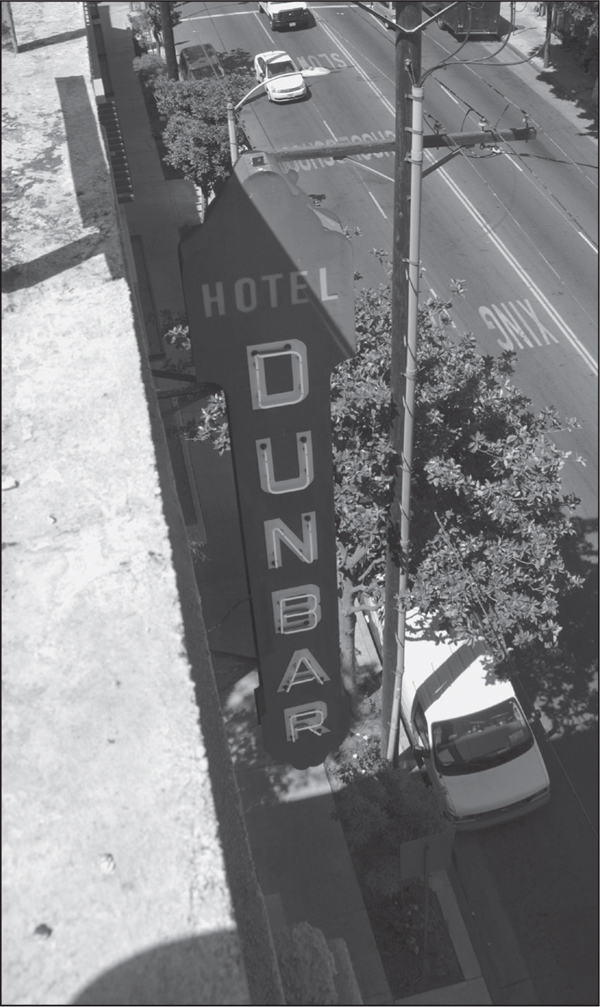

The same Dunbar sign has hung on the north corner of the building since the 1930s. It is visible on the postcard on page 26. The sign got a boost of new neon when the building was renovated, and it now glows nightly above Central Avenue.

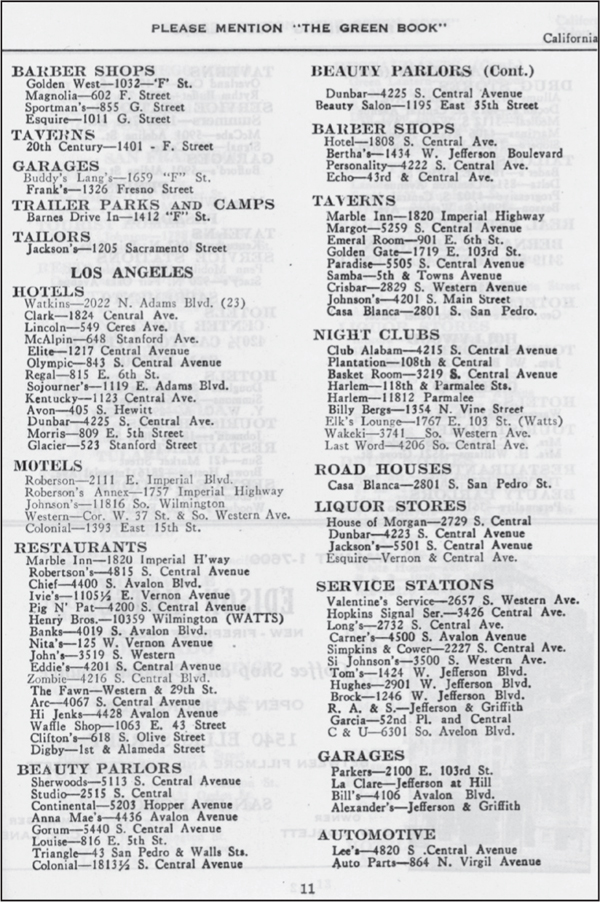

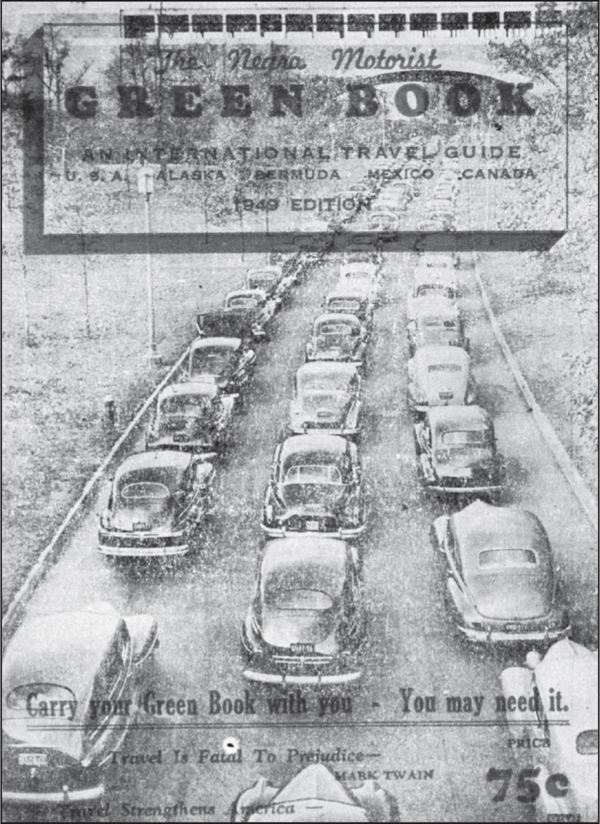

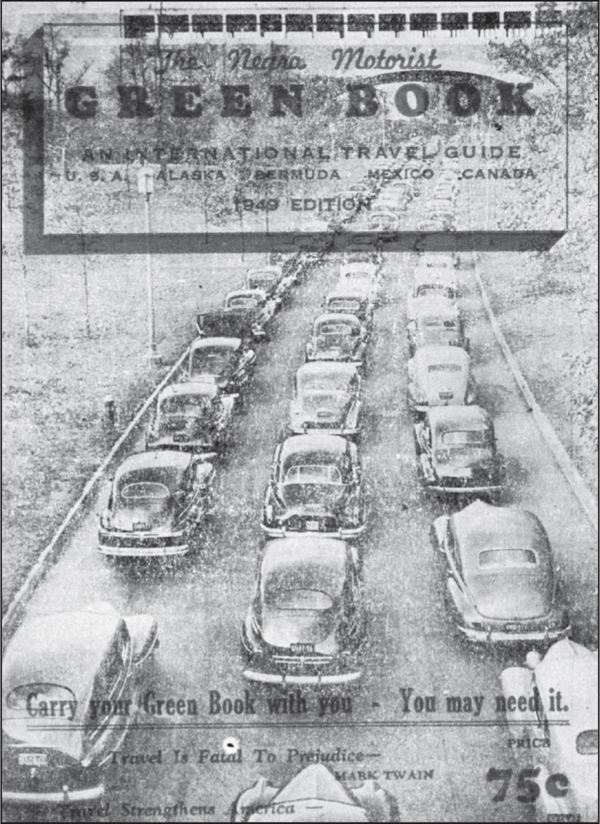

The Green Book was an essential guide for African American travelers in unknown and inhospitable areas of the United States. Independently compiled, the guide offered the locations of hairdressers, restaurants, nightclubs, and lodgings that were friendly to out-of-town African Americans. The listing for Los Angeles shows how many of these businesses were clustered around Central Avenue. The guide was indispensable in helping travelers to avoid confrontation and to maintain their dignity in the face of bigotry.