A HISTORY OF THE STUDY OF CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

DEPARTMENT OF MARKETING, UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA, TUCSON, AZ, USA

When Michael Solomon invited me to contribute to this volume, he suggested that I might tell what I think a scholar in the field of Consumer Behavior (CB) should know about what has been done, and what needs to be done in the future. I appreciate the generosity of the invitation. I will take his suggestion as a mandate and try to fulfill it. In doing so I will explain what I think is the domain of the study of consumer behavior, how it has been studied in the past, and how my own awareness and study of consumption came about. Then I will note the current nature of such study and where it might go.

My interest in history was stimulated and inspired by my World History class in high school and exposure in college to Herodotus, known as the “father of history” and Thucydides, known as the “father of scientific history.” Both wrote in the 5th century BCE about war, among the Greeks and between the Greeks and the non-Greek, telling of their travels and data-gathering. I have thus similarly written about the field of marketing and consumer behavior and my role in thinking about it, given different contexts and purposes, including my travels and methods of data-gathering (Levy 2015a, 2014a,b, 2006, 2003).

When we speak of consumer behavior, we commonly have in mind the things that people buy for food, shelter, and clothing, with consuming especially meaning using something up as in eating. But modern understanding of consumption does not actually exclude anything that is consumed by the body or mind. That is to say, all behavior is a form of consumption of some kind. Given that fact, it is of interest to explore how thinkers have conceived of it in the past. We can distinguish among such ideas as the nature of consumption, thoughts about it, attitudes toward it, and perhaps theories about it. One way to come at it is to focus on the consumption of food, as it is clear that the topic of the consumption of food is a primary issue in the study of marketing and of consumer behavior.

Consuming as Cooking and Eating

I like to go back and see what the literature and artifacts of early days tell us about what people consumed and how it was perceived. Scholars may not have studied it specifically as they do today, but they inevitably thought about it from whatever might be the perspective of their role at the time. With that in mind, I asked what we know about the eating and drinking of the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans, which is quite a bit. In Egypt, a lot of data comes from paintings of banquet scenes, from the contents of tombs, and writing on stelae and papyrus. There were strong influences from both Asia and Africa and a quite varied diet was available in meat, vegetables, and fruit, with the use of barley to make beer. Although not “scientific studies,” the early literature gives us significant reports of what was consumed, its symbolic meaning, and its important relationships to the culture of the community. For example, one story from over 3000 years ago in The Literature of Ancient Egypt (Simpson 1973), tells us that the king, presumably in sympathy and to comfort, rewarded a priest lector, husband of an adulterous wife, “a large cake, a jug of beer, a joint of meat [ox], and one cone of incense.” For a summary of ideas about food in ancient times, I refer the reader to an excellent, relevant website: www.cooksinfo.com/food-in-ancient-greece. There, and elsewhere, in the original writings, we can learn what Homer and Aristotle thought, and that Archestratus was a gastronome who wrote poems about food (as in the current vein of the Consumer Culture Theory poets) that were controversial and said to corrupt the reader with ideas about luxury rather than a more virtuous austerity. Plato thought that consuming the arts was so strong in shaping character that they had to be severely controlled in his ideal Republic.

The Greeks distinguished their civilized ways from those of barbarians whose use of butter, for instance, was frowned upon, and considered the Persians self-indulgent. The relation of food and alcohol to their potential for carousing is well documented: Dionysus was the god of orgies and drunkenness. As an aside: I have a special affection for Dionysus. His name was sanctified as St. Dion to make Christianity more palatable to Greek pagans. St. Dion morphed into the French St. Denis (pronounced Sahndahny), which crossed the English Channel to become Sidney. I relate this to change the perception of my brand.

The Satyrican of Petronius (1st century A.D.) includes a fabulous celebration of the bacchanalian approach to eating at elite Roman banquets, and reflects the consumption of wealth, indolence, hedonism, and vulgarity. Jumping the centuries, that brings to mind the vision of Henry VIII pork-gorging himself on a large roasted leg, portrayed by Charles Laughton in the 1933 film of The Private Life of Henry VIII. The sheer pleasurable greedy aspect of eating may be a neglected topic in recent studies perhaps because of our concern with obesity and an ambivalence about criticizing heavier people. Historically, among thin poor people a stout wife was prized as a sign of a man’s success; and the obese King Farouk of Egypt was rewarded with his weight in gold on his birthday. In the 1920s, passersby were said to admire (envy?) a millionaire, the large Diamond Jim Brady and voluptuous actress Lillian Russell stuffing themselves conspicuously in the windows of Delmonico’s restaurant, also demonstrating a link between wealth and gluttony.

The literature of the Middle Ages is also highly informative. For example, this website, www.lordsandladies.org/middle-ages-food.htm, describes the cultural diffusion of more than food due to the travels of Crusaders: “The elegance of the Far East, with its silks, tapestries, precious stones, perfumes, spices, pearls, and ivory, was so enchanting that an enthusiastic crusader called it ‘the vestibule of Paradise’.” Travel certainly broadened the mind of the Crusaders, who developed a new and unprecedented interest in beautiful objects and elegant manners. The website notes that:

the preparation of Middle Ages food was of special interest to the women of the era, many of whom accompanied men on the Crusades. The preparation and content of Middle Ages food underwent a sea change – into something rich and strange.

(www.lordsandladies.org/middle-ages-food.htm)

A wonderful contribution comes from Stephen Mennell (1985). All Manners of Food presents eating and taste in England and France from the Middle Ages onward. It is a richly detailed treatise, informative and stimulating in its variety and breadth of topics. The traditional perception of the superiority of French cuisine is exemplified by the work of Brilliat-Savarin (1825), The Physiology of Taste. It is probably the most famous historic work by a gastronome, with gastronomy defined as “the art and science of delicate eating.” As Mennell notes, although designed for the elite, gastronomic writing has served to democratize these ideas.

More recent cookbook writing by the lively Julia Childs and the thoughtful, sensitive essays by M.F.K. Fisher (The Art of Eating 1954) have spread the word about the way food and its preparation are to be experienced and appreciated and have affected the contemporary interest in chefs, cookery, and restaurant attendance. Fisher writes about “Cultural issues, differences between social classes and eating customs, attitudes toward diet, etc.” Her thoughts are echoed by the impressive volume, Larousse Gastronomique, which says,

Dining partners, regardless of gender, social standing, or the years they’ve lived, should be chosen for their ability to eat – and drink! – with the right mixture of abandon and restraint. They should enjoy food, and look upon its preparation and its degustation as one of the human arts.

Its advertisement says that “it presents the history of foods, eating, and restaurants; cooking terms; techniques from elementary to advanced; a review of basic ingredients with advice on recognizing, buying, storing, and using them; biographies of important culinary figures.”

Also significant to this history of the promotion of good eating, is the famed chef Escoffier whose consumers included kings and presidents at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel. I visited his museum in Villeneuve-Loubet, France, collected menus, and used his Sauce Diable when making devilled eggs. I was irked when the Nabisco Company evinced some mystique marketing strategy when it acquired Sauce Diable and Sauce Robert and then killed them both.

Consuming by Wearing Clothes

The history of clothing may be similarly examined to show how consumer behavior has become known to us. While food is necessary to sustain all vital life among animals, clothing is almost totally customarily consumed by human beings, with various degrees of coverage ranging from some naked groups to women covered totally by a burqa. There is a lot of history about clothing behavior, including theories that place its origins with estimates from 170,000 to 540,000 years ago. Compared to the study of food consumption, CB scholars seem less given to analyzing behavior with clothing despite Michael Solomon’s innovative doctoral dissertation on the phenomenon of “dress for success.” However, the International Textile and Apparel Association publishes its own journals that focus on (among other topics) how consumers use clothing symbolism to regulate their lives and self-concepts. Also, an interesting background volume may be found on the internet at www.amazon.com/Psychology-Fashion-Advances-Retailing. Another exception is the work by one of my former doctoral students in his e-volume on The Luxury Strategy (Kapferer and Bastien 2009). As a comprehensive analysis for marketers, it touches on diverse realms of luxury consumption, including transportation, which seems another area neglected by CB scholars.

A concern with fashion is of course a concern with the effects of the passage of time and changing circumstances. The consumption of both food and clothing shows the basic influences of the local environments, the climate, and the substances available to feed and cover the body: that is, what is essential and what is possible. But there are always choices to be made, and implications, ramifications, and complications naturally arise. Over time changes in consumption are created by innumerable variables of age, gender, social status, laws, religious belief, aesthetics, and the cultural effects of these, such as technology, education, war, and so on. The same is true of shelter, with the many architectural variations from stone cliff-dwellings of Pueblo Indians (Benedict 1934) to so-called McMansions of the suburbs (Craven 2016). Curiously, again, the study of shelter appears rarely in journals of consumer behavior, despite the widespread attention given it by other media that illustrates its importance to consumers. Still, a valuable background resource is available on the web at Amazon.com that concerns the psychology and sociology of home decoration.

Studying Consumer Behavior, the Grand Topic

An influential treatise such as Max Weber’s (1905) The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism explores relationships between economics and spirituality and while it does not speak about the minutiae of consumption in everyday life, the principles and grand guides radiate into desirable and undesirable choices of behavior, as most religions bring along ideas about what foods should be eaten, what clothes should be worn, and strictures about whatever is forbidden.

All these issues result in how people think about their conformity to custom and their presentation of themselves as individuals, thus radiating into grooming, cosmetics, and the endless ways in which they develop their daily consumption. I say all this mainly to set the stage for the more personal view that the editor asked of me. It is a way of saying what a grand topic I consider the subject of consumer behavior to be. It becomes an excuse to study whatever comes to mind, as I have done with the subjects of the arts, death, the telling of lies, and the enjoyment of poetry, as well as the conventions of eating and drinking (Levy 1963, 1996). I will not go into the same detail I have given in several articles and a couple of autobiographical books (One Man in His Time 2014b, A Marketing Educator’s Career 2015b), and will focus mainly on the way consumer behavior has been studied and is being studied, by me and by others.

There is probably no specific point at which the study of consumer behavior began, since observing it has obviously gone on since it started, and I will not belabor the point by citing any more of the early observers throughout history. However, in more recent modern times there have been thoughtful scholars who studied and reflected on consumption in various ways, whether or not as “scientific fathers.” Before coming to the 20th century, a most remarkable work should be recognized. That is The Theory of the Leisure Class by Thorstein Veblen (1899). It is defined as a study in economics, a wonderful exploration of a segment of society described as nonproductive and devoted to “conspicuous consumption.” As often happens with original work, it was severely criticized. “Such books as this bring sociology into disrepute among careful and scientific thinkers” and the references to economics are “ill-considered and vicious” (quoted from the Yale Review on the 1945 book jacket). Veblen’s work has outlived that of his critics, a fact that gives me comfort when my work is disparaged or misunderstood by reviewers.

A study that might be regarded as a follow-up on Veblen is Leisure in America by Max Kaplan (1960) where he says Veblen’s work is “famous and important,” and discusses the concept of leisure in a highly ramified way, and is not confined to the upper class. It is an excellent example of how sociologists have studied consumer behavior although Kaplan tends not to refer to it that way. Kaplan also finds scholarly criticism. The anthropologist, W. Lloyd Warner, was one of my professors, mentors, and a colleague at Social Research, Inc. (SRI). He is roundly denounced for his work on social stratification: Pfautz and Duncan (1950) call it irrelevant, technically deficient, weak, inadequate, theoretically uninformed, and ideologically suspect. Despite those “ill-considered and vicious” comments, Warner’s work was useful to us at SRI, helping in the study of consumer behavior among social class groups. We used Warner’s Index of Status Characteristics to measure the social positions of all our respondents, thus being able to show important similarities and differences in their consumption patterns. We wrote about them in several publications: Living with Television (Glick and Levy 1962), Workingman’s Wife (Rainwater, Coleman, and Handel 1962), And the Poor Get Children (Rainwater 1963), “Social Class and Consumer Behavior” (Levy 1966).

Another notable anthropological contribution is the work of Audrey Richards (1932) who studied consumption among the Bantu people of Africa during the late 1920s and early 1930s. Her great classic report, Hunger and Work in a Savage Community was considered ground-breaking work in anthropology. In homage, I wrote “Hunger and Work in a Civilized Tribe, The Anthropology of Market Transactions.” (Levy 1978). A similar modern full-scale work is Consumer Passions: The Anthropology of Eating, by Farb and Armelagos (1980). And Ruth Benedict’s Patters of Culture (1934) should be a basic source for students of Consumer Culture Theory. Along this line of studying society in the context of the time is the writing of Richard Tawney (1921). He discussed the relationship between economics and spirituality in The Acquisitive Society, serving as an updated discussion of Max Weber. He is also more judgmental about his analysis, titling his book originally as The Sickness of the Acquisitive Society.

The Consumer World After World War II

In the late 1940s and 1950s, with the post-war upsurge of prosperity, competition, and consumer choice, several social commentaries appeared. Riesman (1950), in The Lovely Crowd, compared the behavior of inner-directed and outer-directed people. Galbraith (1958), in The Affluent Society, argued against wasteful advertising and urged spending on the public good. Lewis (1959), in Five Families used a case study approach to theorize about what he termed The Culture of Poverty. McClelland (1961), in The Achieving Society studied the force of the achievement motive and other factors that brought about successful results. These works were all ways of studying consumer behavior, depending on their circumstances and their motivations.

Most rewarding and illuminating in a more specific and focused vein is Daniel Horowitz’s (1985) study of The Morality of Spending, Attitudes Toward the Consumer Society in America, 1875–1940. I wrote an article (Levy 2014a) called “Olio and Intègraphy as Method” that recommended gathering, interpreting, and integrating data from different sources to arrive at an analysis of a situation. I was referring to a procedure, an olio, that includes curating an exhibit or collection, creating a montage, using a recipe, and so on, but was criticized for creating a mere hodgepodge. I was pleased that Horowitz’s book was admired in the American Historical Review, which said that he “has made creative use of diverse sources in order to integrate several fascinating strands of American culture history.”

At the other end of a spectrum from such studies characterizing the behavior in whole societies are full intensive studies of specific products and their use. The Bathroom by architect Alexander Kira (1966) is one example, as he analyzes the design of a commode that would be better for consumers (or eliminators in this case). A delightful book is William A. Rossi’s (1976) The Sex Life of the Foot and the Shoe. Rossi’s complete devotion to his subject matter is exhilarating and attests to the value of such specialization, analogous to the more recent way Brian Wansink concentrates on the conception and consumption of food; and as I have obsessed about the practical and symbolic significance of branding (Levy 2016).

A Personal Role in Consumer Research

I have covered this topic in “Marketing Management and Marketing Research” (2012), and will summarize it here. Social Research Inc. was created in 1946. I joined it in 1948, working part time while a doctoral student. Shortly afterwards I joined and worked full time until 1961 when I became a professor at Northwestern University. Along the way, I became a principal in the company. Although full time at Kellogg School I continued to handle projects at SRI as we more or less flourished through the 1960s and 1970s. But then we had trouble staffing with people who could do sophisticated qualitative research and top people had gone off. Lee Rainwater went to Harvard, Richard Coleman to Kansas State, Gerald Handel to CCNY, and Ira Glick to his own firm, and so on. Burleigh B. Gardner, famed for his major work, Human Relations in Industry and our company head, was aging but he and I held things together for clients up into the 1980s.

The company had sort of petered out, but we worked independently for people who knew us personally as we did no formal promotion. Burleigh died in 1984. By then the office was closed, all the files were moved to an office in my house where I continued to work on projects (with some helpers) while devotedly doing my job at the university as head of the doctoral program (1962–1980) and then head of the department (1980–1992). Here is a partial list of proprietary studies I did in SRI’s name during that time that shows the variety of subject matter that enabled me to learn a lot about consumer behavior as we interviewed many people about these several issues.

The Meanings of Milk (J. Walter Thompson, 1981)

A Qualitative Study of Apparel Emblems (Sears, 1981)

Hotel Attitudes and Images (JWT, 1982)

Home Video Games: Motivations, Perceptions, Satisfactions (JWT, 1982)

Communications from Philadelphia Cream Cheese, (Kraft, 1982)

Acne: Concerns and Regimens (Abbott Laboratories, 1982)

The Home Computer Market (Activision, 1983)

The Meaning of Wine (JWT, 1983)

The Image of Archivists: (Society of American Archivists, 1984)

Physician Attitudes toward Pain and Pain Relief (Upjohn, 1987)

The Meaning of Flowers (D’Arcy Masius Benton & Bowles, 1987)

You can see how I had such a great opportunity to learn about the managerial issues of relating to consumers. Also, because we did work for associations, hospitals, newspapers, schools, and so on, I learned that consumers and those managers are everywhere. That led to my writing about “Broadening the Concept of Marketing” (Kotler and Levy 1969) and to my book The Theory of the Brand (2016), to reflect on their universal applications. The many interviews we gathered in the course of conducting all these projects kept showing how consumers found meaning in the people, objects, and experiences in their lives, intensifying my appreciation of the role of symbols that I wrote about in “Symbols for Sale” (1959) after expressing those ideas in a talk called “Symbols by Which We Live,” at the American Marketing Association Summer Educators’ Conference in Chicago in 1958. As part of this broadening, I studied consumers of government agency services (Levy 1963). I met with groups of museum personnel who began to think of their members, donors, visitors, program attenders, as consumers also, in addition to the gift shop customers; and the Art Institute of Chicago for the first time sought a director of marketing.

As the study of consumer behavior grew so notably in the field, it also gained academic attention. At Northwestern University School of Business Marketing Department, which I joined in 1961, I was preceded by Steuart Henderson Britt. He started there in 1957 and taught one of the first courses in consumer behavior. He was a remarkable scholar with an astonishing vita as a lawyer, psychologist, sociologist, business executive, consultant, and so on. He edited the Journal of Marketing for ten years. He conducted many studies of consumer behavior and was a strong believer in the value of empirical inquiry and the role of advertising; and he wrote a little book about The Consumer as King. I saw him as a model for a comprehensive, multidisciplinary understanding of marketing and the study of consumer behavior.

The Entrenchment of Consumer Research

It took a while for consumer study and instruction to become fully established through the 1950s and 1960s. Although Division 23 of the American Psychological Association focused on consumers, it did not start the Journal of Consumer Psychology until 1992. But 1970 and 1974 saw the birth of the Association for Consumer Research and the Journal of Consumer Research, making the study of consumer behavior full scale and front and center, with the journal having a policy board with representations from the anthropological, sociological, psychological, and statistical associations. By then most academic marketing programs had courses focused on consumer behavior.

At present, the study of consumer behavior is diverse and multi-faceted although the Journal of Consumer Research and the Journal of Consumer Psychology and their associations appear concentrated on the psychology of consumer decision-making and engage increasingly in abstract language. Mainly housed in academic marketing departments, the researchers seem primarily engaged in experiments that are remote from dialogue with marketing practitioners and their problems. As a consequence, other entities arose with interest in a broader understanding of consumer life. Thus, we now have the journal of Consumption Markets Culture, the vigorous international membership of the Consumer Culture Theory and the new Journal of the Association for Consumer Research. Personally, I applaud these developments because my work has always derived closely from my experience with empirical and pragmatic studies of consumers in their everyday lives. My thinking these days is guided by two general perspectives that I will share as a source of recommendations for future study of consumers.

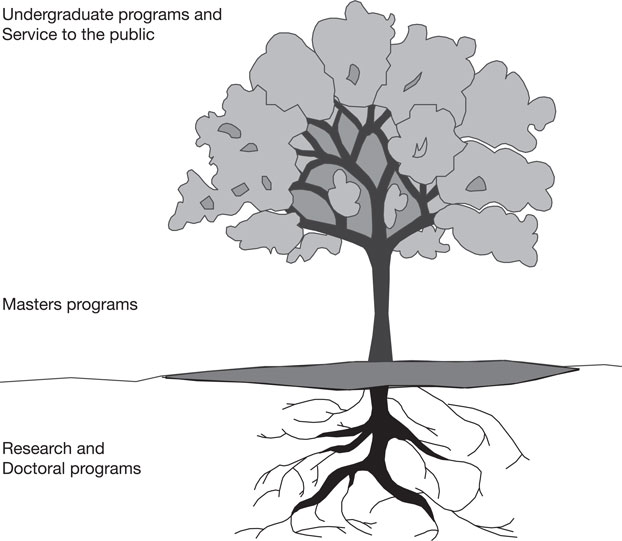

Levy’s Academic Tree

In this organic metaphor, the roots are the research program and what it implies for faculty participation in the academic community of scholars, journals, and conferences, preparing researchers and teachers, being part of the international scene, and so on, even if, like roots, they are not so visible to the casual observer or understood by the practitioners. The roots are not apparent and not visibly beautiful and attractive, like the enjoyable proliferation of leaves, flowers, and fruit, but are essential to the nourishment and growth of the tree. So, too, the necessity for the doctoral program and all that it implies in basic inputs, growth of knowledge, training for the future, and a natural and critical investment for a significant educational program. Without a strong and well-fertilized root system (funded by “rainmakers,” and respected by supporters among the public, alumni, legislators, etc.), the academic tree will be stunted in its personnel, richness of insight, and quality of product. To deny the need for this support is a foolish “know-nothing,” anti-intellectual attitude that does not understand the role and necessity of basic research whose practical value may not be immediately apparent. Some schools recognize the necessity for a doctoral program and even in the U.S. the system pays graduate students with tuition and stipends to work toward their doctorates. It is a marketing system in which schools woo students to apply and students woo schools for admission.

The trunk is the Masters programs, MBAs, executive education seminars, and consultancies, whereby the esoteric studies and abstractions that root the tree are translated into theories of strategy and practice. The trunk is sturdy, branching into different areas of specialization, determining policy and the shape of the enterprise. Fed by the root system, the managerial trunk is important for carrying leadership and direction to the world of action and application.

The foliage, flowers, and fruit are the undergraduate programs and service to the public. These products of the academic tree benefit the general community, providing knowledge and experience for the everyday labor market. Through direct instruction in the classroom and via the training of higher level managers, the research faculty disseminates their learning.

I like to use Levy’s Academic Tree (Figure 1.1) to think about roles within schools dealing with their many required and related tasks. At every level the participants may be viewed as consumers of their education. I studied students as such and also as consumers of my courses, as we marketed ourselves to each other. I helped graduates of the doctoral program get jobs at other schools, writing letters to advertise their merits on the labor market. In these various situations, we all engage in exchanges of our services, supplying and receiving as providers and consumers. Sometimes we study as participant/observers and sometimes conduct formal studies. I asked students in the “subject pool” what behavior they did that they knew was wrong but did it anyway; and why they did that. Another time, I studied alumni of the University of Michigan for an officer of the university about their attitudes and actions toward giving. After Philip Kotler and I wrote “Broadening the Concept of Marketing,” in 1969 more schools created directors of marketing or of advancement, and study their students as consumers in detail, despite those who dislike thinking of students in that way and debate whether students are consumers or products. They are certainly customers when they borrow large sums to pay for their instruction.

Figure 1.1 Levy’s Academic Tree

The Ideal Brand Pyramid

The Ideal Brand Pyramid (IBP, Figure 1.2) is a diagram that I use to sum up all the inputs into the creation of a brand, a brand being any identified and named offering. I have detailed what I consider the nature of branding in the text, The Theory of the Brand (2016). There I define branding as more than just the name of a trademarked product, but as the character and reputation of an offering that are gained by its purpose and actions, whether in commercial exchanges or other spheres of providing and consuming.

The IBP builds on Aristotle’s analysis of Rhetoric as ethos, pathos, and logos. In the diagram, the lower left corner refers to all the elements that have to do with the nature of the offering. The offering may be a commercial product, a person in the labor market, or individual in a social setting. The IBP tells its technology, its function, its attributes and benefits, including its value and validity; and the means by which it is made available, whether in the marketplace, the workplace, or the home. All that is summed up as its function, its character, its ethos. Historically, this is the realm of traditional marketing concerns with product and distribution. It also represents the recent stress on innovation as well as the conflicts about the effects on the environment and the treatment of suppliers that animate the Critical Theorists.

The right corner of the IBP refers to all the elements that have to do with the human interactions of the exchanges between the providers and the receivers. That then entails the social relationships of the participants, their cultural customs, and their individual motivations, cognitions, and emotions, thus their pathos. These are the issues of consumer behavior and the activity of consumer research, as well as the contemporary idea of co-creation (Lusch and Vargo 2006).

Figure 1.2 The Ideal Brand Pyramid

The world of marketing has grown with globalization, as the interest in segments of the populations has risen, as the complexities of relating to individuals, social groups, and different cultures have all become more challenging. As a consequence, there is increased concern with how to present the offering. This concern is fundamentally a concern with aesthetics, summarized here as the logos. The logo refers to the word, and then to the logo, that is what to say and what to show, ultimately, how to appeal to the senses of the audience, whomever the consumer may be. The thoughtful presenter – manager or any individual – has to think, wherever relevant, how the offering and its surroundings should look, feel, taste, sound, and smell. These aesthetic elements bring forward the role of art, design, of music, and the character of the environment. Thus, the task of modern managers at the peak of the IBP is to integrate these three basic realms of marketing to communicate to and interact with their chosen audiences, to define, portray, and proclaim their purpose, what they have to offer and what they want to receive.

Suggestions for Future Work

The study of consumer behavior is flourishing. The growth of the adherents to Consumer Culture Theory and the creation of The Journal of the Association for Consumer Research are testimony to that. From my overview here, I derived these suggestions.

To a history-minded fellow such as I, there seems never enough historical study. Brian Jones and Mark Tadajewski labor assiduously in that vineyard, as does Jagdish Sheth; and I recommend others should join them in enhancing our knowledge of what has been done. The study of history is itself a form of research method. Much more might be done to increase our understanding of research method; the various ways science expresses itself. That might help to counteract the parochialism that appears to afflict scholars overly devoted to their tools and hostile to others.

Some areas of study do seem to be slighted by scholars in our field. Since so much contemporary research seems addressed to the psychology of consumers, attention tends to focus on motives as variables, both dependent and independent. Often, their abstract character tends to obscure the effects on daily life of consumers and the actualities of their consuming. One factor that seems to contribute is the over-use of the word “brand” to refer to any and all products rather than naming them and the specific context for marketing interaction.

In aiming for generality, we tend to lose specificity. It is a way of pretending that specific contexts do not matter, whereas contexts are often what people care about. A study that quotes the purchase categories at issue as including “groceries, gasoline, apparel,” is of interest to us grand theoreticians, but needs some more offsetting by the importance of what is often shunted aside as “individual differences.”

I cannot know the total literature, but if I am correct the contexts of clothing and shelter do seem underplayed, and could afford more attention along the lines of Guliz Ger (Sandikei & Ger 2010) on head scarves and why gatherings of business people on formal occasions look like a group of penguins in their black suits. And speaking of gatherings, does our literature give sufficient attention to the consumers of conferences, protests, rallies, funerals, concerts, and the roles of economics and technology besides the pervasive absorption with “social media.” The intellectual opportunities abound.

References

Benedict, R. (1934). Patters of culture. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Brilliat-Savarin, J. (1825). The physiology of taste. Paris: Courier Corporation.

13Craven, J. (2016). Architecture. Online (www.thoughtco.com/styles-of-architecture-4132951) accessed May 2017.

Farb, P., & Armelagos, G. (1980). Consuming passions. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Fisher, M.F.K. (1954). The art of eating. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Galbraith, J.K. (1958). The affluent society. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin Co.

Glick, I., & Levy, S.J. (1962). Living with television. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Horowitz, D. (1985). The morality of spending. Chicago, IL: Ivan R. Dee, Publisher.

Kapferer, J.N., & Bastien, V. (2009). The luxury strategy. London: Kogan Page.

Kaplan, M. (1960). Leisure in America. New York: NY: Wiley & Sons.

Kira, A. (1966). The bathroom. New York, NY: Viking.

Kotler, P. & Levy, S.J. (1969). Broadening the concept of marketing. Journal of Marketing, 33, 10–15.

Levy, S.J. (1959). “Symbols for sale,” Harvard Business Review, 37, 117–124.

—— (1963). “Symbolism and life style,” Proceedings, American Marketing Assn, 140–150.

—— (1966). “Social class and consumer behavior,” in Joseph Newman (ed.), On knowing the consumer, New York, NY: Wiley & Sons.

—— (1978). “Hunger and work in a civilized tribe,” American Behavioral Scientist, 21, 557–570.

—— (1996). “Stalking the Amphis baena,” Journal of Consumer Research, 23(3), 163–176.

—— (2003). “Roots of marketing and consumer research at the University of Chicago,” Consumption, Markets, Culture, 99–114.

—— (2006). “History of qualitative research methods in marketing,” in Russell Belk (ed.), Handbook of qualitative research methods in marketing, 3–16.

—— (2012). “Marketing management and marketing research,” Journal of Marketing Management, 28, 8–13.

—— (2014a). “Olio and intègraphy as method,” Consumption, Markets, Culture, 18(2), http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2014.968756.

—— (2014b). One man in his time. Tucson, AZ: Amazon.com.

—— (2015a). Roots and development of consumer culture theory. In A.E. Thyroff, J.B. Murry, & R.W. Belk (Eds.), Consumer culture theory (pp. 47–60). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

—— (2015b). A marketing educator’s career. Evanston, IL: DecaBook.

—— (2016). The theory of the brand. Evanston, IL: DecaBooks.

Lewis, O. (1959). Five families: Mexican case studies in the culture of poverty. New York: Basic Books.

Lusch, R.F., & S.L. Vargo (eds.), (2006). The service dominant logic of marketing. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

McClelland, D.C. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton, NJ: Nostrand.

Mennell, S. (1985). All manners of food. New York, NY: Basil Black, Inc.

Pfautz, H.W., & O.D. Duncan (1950). “A critical evaluation of Warner's work in stratification,” American Sociological Review, 15(2), 205–215.

Rainwater, L. (1963). And the poor get children. Chicago, IL: Quadrangle Books.

Rainwater, L., R. Coleman, & G. Handel (1962). Workingman’s wife. New York, NY: Oceana Publications.

Richards, A. (1932). Hunger and work in a savage community. London: Psychology Press.

Riesman, D. (1950). The lovely crowd. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Rossi, W.A. (1976). The sex life of the foot and shoe. New York, NY: Dutton.

Sandikei, O., & G. Ger (2010). “Veiling in style: How does a stigmatized practice become fashionable?” Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 15–36.

Simpson, W.K. (1973). The literature of Ancient Egypt. New Haven, CT: Yale University.

Tawney, R. (1921). The sickness of the acquisitive society. London: The Fabian Society.

Veblen, T. (1899). The theory of the leisure class. New York, NY: Viking Press.

Weber, M. (1905). The Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. London: Unwin Hyman.