CO-CONSTRUCTING INSTITUTIONS ONE BRICK AT A TIME: APPROPRIATION AND DELIBERATION ON LEGO IDEAS

1DEPAUL UNIVERSITY, CHICAGO, IL, USA

2ESCP EUROPE BUSINESS SCHOOL, LONDON, UK

The LEGO Group offers thousands of model kits for sale globally, and one source of ideas for new kits is LEGO consumers. Firms that want to use consumer ideas can actively partner with consumers, they can borrow ideas from them, or they can even steal ideas from them. Consumer research has recently begun exploring how firms can effectively partner with consumers to develop products and brand experiences, a phenomenon frequently labeled as “cocreation.” In this chapter, we use the LEGO brand as a context to explore the rules and tensions of cocreation.

Consumer cocreation is a prominent topic in the contemporary marketing trade press and is commonly observed in the lives of brands and consumers. Technology has enabled the development of platforms on which different kinds of contributors can exchange ideas, and as a result, many firms have launched collaborative programs in which they encourage customers to suggest product ideas and other innovative inputs. While many firms understand the potential benefits of integrating external resources, they often confront significant challenges and obstacles in doing so. The logic motivating or guiding externally performed activities may be incompatible with internal processes, practices, and standards. The president of the crowdsourcing development firm Topcoder wrote for Wired magazine that a substantial number of firms will attempt and then abandon cocreation of innovation when it fails to engage consumers and/or improve firm innovation:

At the onset of 2014 we find crowdsourcing where cloud was just a few short years ago – widely discussed, unevenly adopted and on the cusp of widespread industry impact. Similarly, we will see crowdsourcing experience hypergrowth but also leave some damaged bystanders that were caught up in the hype and mislead [sic].

(Singh 2014)

As with many revolutionary changes, the hype might exceed practical understanding.

There are many potential sources of frustration in cocreation. Leveraging firm-led user communities is cost-intensive and difficult to manage, and it precipitates “a loss of control on the part of the producer firm” (Hienerth, Lettl, and Keinz 2014, 851). Managers may find customer ideas redundant, unattractive to mass markets, or otherwise impractical (Bayus 2013). They may find themselves overwhelmed by the volume of customer ideas (Gloor and Cooper 2007). Other challenges include designing appropriate interface mechanisms (Terwiesch and Xu 2008), recruiting qualified contributors (Jeppesen and Lakhani 2010), and managing the process (Füller, Hutter, and Faullant 2011; Singh 2014). It is not surprising that many of these ventures fail. Some prominent documented failures include the Campbell Soup Company (Phillips 2011), CrowdSpirit (Chanal and Caron-Fasan 2010), Genius Crowds (Crowdsourcing.org 2013), and Naked & Angry (Weingarten 2007). Many factors explain these failures, but a common element was creativity at the expense of marketability. Creativity does not necessarily translate into salability.

Despite the risks, however, ignoring cocreation opportunities is problematic for two reasons. First, customers tend to expect that their contributions to a brand or product will be met with gratitude or some form of recognition (Füller et al. 2009; Gebauer, Füller, and Pezzei 2013). This expectation may be more pronounced when contributions are made publicly and gather significant support from communities and other institutions (Muñiz and O’Guinn 2001). Second, evidence suggests that integrating stakeholders is favorable to change and innovation (Taillard et al. 2016; Von Hippel 2005).

Tension clearly exists between the drive to incorporate user input and the myriad challenges in doing so. A prerequisite to resolving this tension is a better understanding of the processes and outcomes of cocreation activities, particularly from an institutional perspective. In other words, we need a better understanding of how the two (or more) entities involved in the cocreation process operate and make decisions. Work on this front is progressing, albeit slowly.

The literature on cocreation is replete with examinations of cocreation practices (Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould 2009), their effects on community building, issues of control and fairness between consumers and firms (Cova, Pace, and Skålén 2015), the different roles that contribute to the cocreation of value (Hartmann, Wiertz, and Arnould 2015), and managerial approaches to cocreation (Payne, Storbacka, and Frow 2008). Much of the literature emphasizes the institutional nature of these activities, as they occur within communities of engaged consumers. What is missing is an account of how these communities emerge as institutions through their collaboration with firms and what these institutional processes mean for the firms and consumer communities.

In making a case for the endogenous role of consumers in cocreating value with a firm, much of the literature has glossed over the existing gap between the consumer community as an institution and the brand or firm as an institution. Consumer communities and firms operate separately, are driven by different purposes, and enact different practices (Skålén, Pace, and Cova 2015). However, evidence indicates that brands and consumers benefit from finding goal congruence (Healy and McDonagh 2013) or practice alignment (Skålén, Pace, and Cova 2015). These accounts are useful in discussing how collaborative practices develop, but they do not address the ongoing recursive effects of the institutionalization processes on the collaboration between consumers and firm (Barley and Tolbert 1997). In other words, while extant research recognizes more or less explicitly that two or more sets of institutional logics are at play, it does not provide a dynamic process-based account of the evolving relationship between the two institutions and their respective logics. This gap is significant: both consumer communities and firms (or their strategies) evolve as they collaborate with each other, and as a result, the consumer community and the firm can develop and exhibit new and/or different practices that, over time, can alter their relationship.

The LEGO Group has developed a strong reputation as a leader in community building and empowering fans to contribute their creativity and building skills to developing new products and fostering engagement (Antorini 2007; Antorini, Muñiz, and Askildsen 2012). In recent years, LEGO has developed a platform on which fans can propose their own models for production. In this chapter, we examine the evolution of practices on the LEGO Ideas platform by analyzing conversations about rules and purposes. These conversations constitute not just a representation of the ongoing collaboration but also the collaborative process itself (Phillips, Lawrence, and Hardy 2004). In other words, we use conversations and online posts as a source of data, a reflection of participants’ intentions and actions, but we are also aware that these posts are actions themselves and, as such, constitute performances of the practices and contribute to the institutionalization process. Thus, we explore the institutionalization process itself by analyzing the effects of participants’ posts on the overall evolution of practices.

Theoretical Foundations

The notion that consumers play a role in the cocreation of brands is well established in marketing. Muñiz and O’Guinn (2001, 412) note that members of brand communities affect perceived quality, brand loyalty, brand awareness, and brand associations: brand community members are coconspirators in the creation of the brand and “play a vital role in the brand’s ultimate legacy.” McAlexander, Schouten and Koenig (2002) build on this thinking and show the effect of other community members on creating excitement and a sense of community around a shared brand consumption event. Camp Jeep and H.O.G. Fests are cocreated between the respective marketers and brand enthusiasts. Kozinets (2002) shows how participants at Burning Man cocreate the event, going so far as to enforce the rules for performance, participation, and observation. Consider also the participants at Burning Man, who create a temporary community in which to practice divergent social logics and escape from aspects of the mainstream market. This sort of user cocreated experience has been soundly demonstrated (Muñiz and Schau 2005, 2007, 2011; Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould 2009).

Consumers can be particularly creative when embedded in communities, and marketers sometimes solicit and use the outputs of these activities (Antorini, Muñiz, and Askildsen 2012; Cova, Pace, and Skålén 2015). Sometimes, these consumers can help evaluate ideas that other consumers generate. Involving the community in the evaluation of consumer-generated ideas can have both positive and negative consequences. For example, the community can drastically reduce the number of ideas internal developers need to evaluate (Filieri 2013). At the same time, consumers might be evaluating ideas in a manner that is inconsistent with the criteria applied by internal developers. A host of positive and negative reactions can result from a community’s satisfaction and/or dissatisfaction with a cocreative process (Kozinets et al. 2010). Hell hath no fury like a cocreative consumer scorned. This is an important consideration, as consumers can hold firm ideas about what is appropriate for the brand, and these ideas need not align with those of the marketer (Muñiz and O’Guinn 2001).

Epp and Price (2011) and Skålén, Pace, and Cova (2015) offer valuable direction here when they note that different parties are likely to have overlapping and distinct goals, potentially leading to both accord and discord. Communities have their own ways of doing things, as do firms. The larger, more developed, and older the community, the more likely it is to be set in its ways. The same goes for the firm. Such entrenched differences can be problematic when they do not align.

Cocreation activities at a process level have received some recent attention in the literature (Epp and Price 2011; Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould 2009; Skålén, Pace, and Cova 2015), but examination of the social aspect of cocreation is still limited (Skålén, Pace, and Cova 2015). Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009) explore how members of nine brand communities created value through 12 practices. They demonstrate that these practices—“linked and implicit ways of understanding, saying, and doing things” (p. 31)—are intricate, pervasive, and organic, possessing trajectories or paths of development that play out over time. This is a valuable insight because it unpacks the cocreative social process, but it suffers from one noteworthy limitation: Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009) treat brand community practices independent of the marketer. They do not consider how community practices might interface with firm practices. In their study, Epp and Price (2011) find that family member relational goals and integration processes affect consumption choices, but they never explore the marketer response. This is a significant gap.

Skålén, Pace, and Cova (2015) successfully bridge this gap. Their netnographic study of the interaction between Alfa Romeo and its fans, the Alfisti (see Alfisti.com), identifies groups of collaborative practices that develop in the cocreation efforts between the firm and consumers: interacting, identity, and organizing. These practices are compelling but, as are those in the work of Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009), are contextually bound. Given that the primary activity on Alfisti.com at the time of the study was organizing the fledgling website as a site for collaboration and preparing for the brand centennial in the following year, it is not surprising that the organizing practice loomed so large here. This was the beginning of Alfa Romeo’s more explicit efforts to cocreate with its consumers. The authors’ assertion that cocreation succeeds when practices align is accurate for the context, but the three practice alignment strategies—compliance, interpretation, and orientation—do not lend themselves to a more established collaborative environment.

While the consumer community research stream shows that communities, as institutions, grow from cocreation actions, the nature of their institutionalization processes remains unclear. Collaboration between customers and firms is still a proverbial black box, with rather robust shortcomings across the disciplines that attempt to illuminate cocreation. This chapter aims to open the contents of that box. In doing so, we build on recent suggestions for further research on specific practices. For example, Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009) suggest that research should attempt to discern and unpack the operation of a broader set of practices. Refining this understanding, they assert, will prove useful in creating novel strategies to further leverage the creative tendencies of marketplace actors.

Practices are routinized actions (Hartmann, Wiertz, and Arnould 2015), and they constitute an aspect of institutions. While the consumer community school addresses some institutionalization processes by showing how communities emerge from consumer practices, it focuses on consumers rather than their relationship with firms and thus fails to answer how practices emerge. We are interested in how institutions such as a firm, a team, a department, or a community, each with their own “institutional logics” or “organizing principles” (Friedland and Alford 1991, 248) of shared understandings and practices, guide and constrain the actions of their members while being “created, altered and reproduced” by these same actions (Barley and Tolbert 1997, 93). Evidence from the public and nonprofit sectors shows that cocreation across institutional boundaries (governments and communities of constituents) indeed fosters the development of new institutions (Lawrence, Hardy, and Phillips 2002). Inclusive public engagement practices by local government institutions can lead to the creation of new institutions (Quick and Feldman 2011). Phillips, Lawrence, and Hardy (2004) also show the role of discourse in institutionalization, a point that is particularly relevant when considering online communities, for which most of the actions of participants are indeed discourse based.

Visconti et al.’s (2010) study of street art and public space is instrumental here. They argue that goods such as public space precipitate contemporaneous, interactive, convergent, and divergent forms of agency because of the multiple entitlements potentially claimed with respect to such goods. There is certainly a parallel between collaborative consumption platforms and these types of public spaces. For example, multiple entitlements can be claimed; that is, the firm and the consumer can lay claim to the nexus of value contained therein. Drawing from the work of Aubert-Gamet (1997), Visconti et al. (2010) identify street artists’ aesthetic space appropriation strategies to symbolically claim public spaces and prevent them from being appropriated by market forces. Similar appropriation strategies could be expected among consumers participating in firm-sponsored collaborative platforms. Consumers might develop strategies and practices that, in turn, allow them to stake a claim.

Method

Field Site

To address the research issues identified, we examine consumer and firm cocreation in an empirical context: the LEGO crowdsourcing platform LEGO Ideas (ideas.LEGO.com). The LEGO brand has been the subject of a great deal of analysis and theorizing. It has also been the topic of general-interest books (Baichtal and Meno 2011), blogs (LEGO.gizmodo.com), magazine articles (Koerner 2006), academic research (Antorini 2007), managerial books (Robertson and Breen 2013), and business school cases (Rivkin, Thomke, and Beyersdorfer 2013) and includes a massive library of design and technique-related writings. We assert that several aspects of the LEGO brand make it a compelling case for theoretical illumination.

First, it returned from the brink of failure by adapting to changes in the sociocultural environment and the ways children play (Robertson and Breen 2013). LEGO figured out how to market building blocks in the age of video games and widespread computing. Second, LEGO has inspired and fostered exceptional community and creativity among its users (Antorini 2007; Baichtal and Meno 2011). LEGO fans, adults in particular, congregate, collaborate, and innovate. They create a substantial amount of brand-related content in a variety of media. Third, LEGO has been successful in leveraging user creativity. Many observers have underscored the active and valuable work of adult LEGO users, supported by employees and managers at LEGO, as an example of successful cocreation (Antorini, Muñiz, and Askildsen 2012; Robertson and Breen 2013). LEGO’s adroit integration of user contributions is atypical and therefore illuminating and allows us to elaborate theory and inform subsequent cocreation efforts.

LEGO Ideas (formerly LEGO Cuusoo) is one of the consumer collaboration efforts by LEGO and one of seven community support programs. In LEGO Ideas, contributors outside the firm are involved in two discrete tasks: idea generation and idea evaluation. LEGO Ideas seeks user ideas for new LEGO kits, and contributors post proposals for new model sets. These include pictures of the fully assembled kit as well as descriptive text and video. Members of the open registration site can comment on the model and vote on whether LEGO should produce the kit. Much of the vote-accumulating process plays out in social media, as various entities advocate for the kits and attempt to drive votes. Proposed kits that receive 10,000 votes are considered by LEGO for official production and evaluated for their commercial potential. Kits chosen for production by LEGO are typically modified to suit in-house preferences and then are manufactured and marketed by LEGO. In return, contributors of the kits chosen for production receive a percentage of sales. In the typology of customer cocreation developed by O’Hern and Rindfleisch (2010), LEGO Ideas represents codesigning, or what Kozinets, Hemetsberger, and Schau (2008) term “elicitation-evaluation.” Analogous examples of codesigning/elicitation-evaluation include the open invention platform Quirky.com, the T-shirt platform Threadless, and watchmaker Tokyoflash.

Data

We drew methodological inspiration from prior work on cocreation practices (Epp and Price 2011; Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould 2009) and institutionalization processes (Barley and Tolbert 1997; Feldman 2004). We used the methods in these studies to structure and organize our observations and analysis. We sought data collection and interpretation approaches that would help us focus on processes and mechanisms. Similar to Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009), we endeavored to move the unit of analysis away from the individual consumer and the firm to the practices and processes evident throughout cocreation activities. Our sampling frame consists of the site guidelines, terms of service, official comments, the site blog, and some relevant threads in social media. Our data include naturalistic observation of firm, consumer, and community activities and archival netnographic research on relevant forums. We observed the forums, downloaded messages, and postings. Because our focus is on the development of processes, we chose to limit our exploration to data that specifically refer to rules, guidelines, practices, and norms. Although other types of interactions among fans and with the LEGO Ideas staff also contribute to the development of processes, they went beyond the primary focus of our analysis.

Analysis

Our analysis of the data proceeded along two complementary tracks. Our first goal was to document the collaborative practices at play on LEGO Ideas, and the second was to explore the underlying recursive dynamics of institutionalization. We coded interactions on the LEGO Ideas platform from the time of the platform’s inception to June 2016. The coding work was done both for fans and for platform administrators. In contrast with the typology of practices proposed by Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009), this list goes beyond consumer practices to include practices performed by both platform users and administrators. As such, it is closer to the typology proposed in Skålén, Pace, and Cova’s (2015) study, which recognizes the collaborative practices performed by members of both institutions. To understand and document the process of institutionalization that takes place as fans and the firm collaborate, we also performed a sequential analysis of interactions on the LEGO Ideas forum since its inception. This analysis was inspired by the methodology that Barley and Tolbert (1997) describe in their article on action and institutionalization.

Findings

Practices and their Trajectories

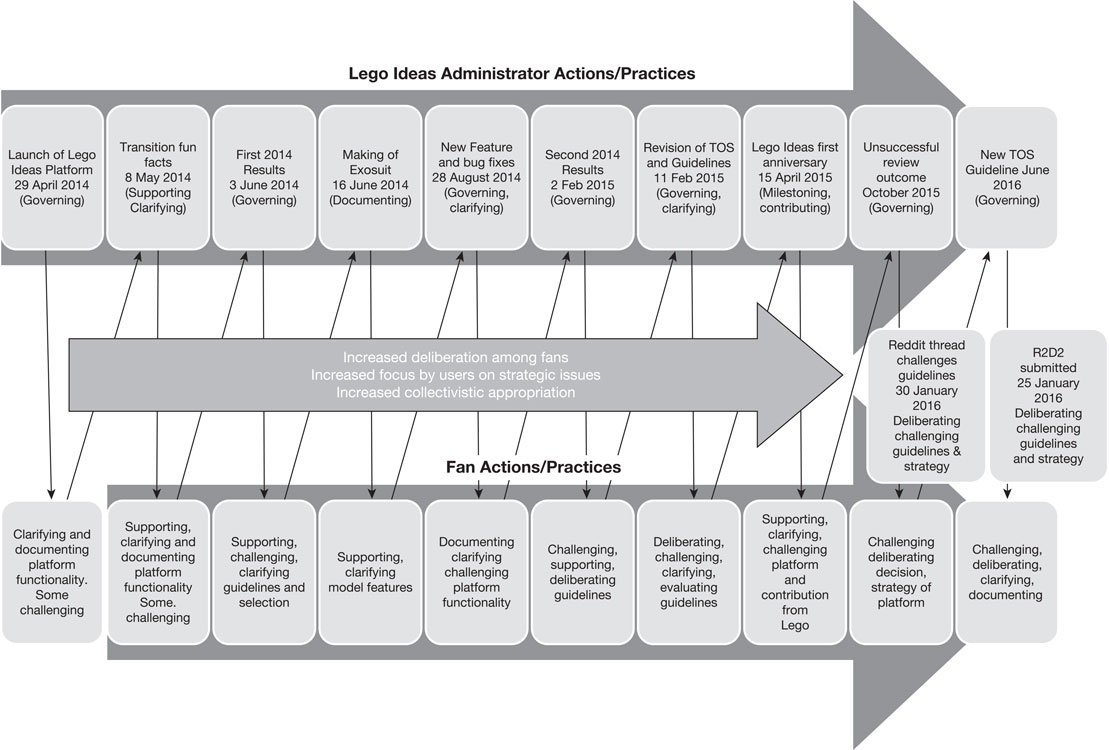

Our coding resulted in the compilation of a list of 13 practices (see Table 26.1). We identified ten main phases of development on the forum itself and two more critical phases (see Figure 26.1): one related to the posting of an R2D2 model on the LEGO Ideas platform (but not on the forum per se) on January 25, 2016, and one related to a Reddit post on January 30, 2016, vehemently challenging the guidelines in effect for LEGO Ideas at that time. Significantly, these two “nonforum” posts were the only ones originated by fans. Both triggered significant subsequent conversations and acted as catalysts for additional forum conversations. Together, these 12 phases reflect the evolution of the collaborative process on LEGO Ideas and provide an understanding of the resulting recursive process of institutionalization.

Table 26.1 Cocreation practice typology

Practice category |

Practice |

Definition |

Illustrative verbatim |

Community Engagement |

Challenging |

Offering critiques of actions by TLG, particularly as they relate to LEGO Ideas and its operation. Challenging the fact that TLG is not playing by the rules that the community is developing and believes they have a right to expect. It is a form of appropriation. The consumer contributor feels they have a right to expect change and or/an answer from TLG. |

Thanks for supporting anyway! I don’t subscribe to the “Lego will never make a different UCS model on the same theme” view. The UCS Artoo was pretty small – besides it wasn’t a Kenny Baker one :) - Besides they could just coin a new term/series if they wanted “Limited Edition Collectible” or whatever. That aside, this one’s going to be a serious challenge for them.” |

Community Engagement |

Clarifying |

Seeking clarification of the rules and purposes of the site. This is similar to what Skålén et al (2015) called “Questioning and Answering.” |

The guidelines say you can’t make level packs for lego dimensions, but can we make fun packs or team packs? |

Community Engagement |

Contributing |

Submitting a kit, voting on a kit, commenting on a kit or promoting a kit. The trajectory of this practice has become more complicated. As LEGO Ideas and its attendant communites have developed, notions of appropriate contributions have evolved. For example, in terms of submitting a kit, designs have become more elaborate. There is more percevied pressure to make something grandiose so as to get social media buzz to drive votes. There is alo more pressure to support kits and not be critical. The trajectory of this practice is creating problems for LEGO Ideas. |

The Kenny Baker Artoo is about 16,000 bricks. Wow! Think about that when supporting, it’s not going to be cheap. This will be the most expensive Lego set by far, but we all know how much fans want this set. Don’t hesitate to sell your car (or at least your spouse’s car) droids are better! |

Community Engagement |

Deliberation |

Frequently co occurs with documenting. Has different categories subsumed within it, these include: 1) the rules of the game, 2) the purpose of the platform 3) justice (is it fair or not)? 4) which of these models is relevant to LEGO’s market? 5) suggest specific additions to the platform. There is a trajectory within this practice to resolve some of the inherent conflicts/ambiguities in Lego Ideas. |

|

Rules of game |

Deliberating and debating the rules of the game |

One question. I have some ideas that are based on certain series and reality shows. The characters in them - at times - curses, smokes and drinks. The TV series and reality shows aren’t themed around cursing/smoking/drinking, but centers around the lives, ups-and-downs, and career advancement of these professionals. Understand that these are not allowed, but is there a way around it? For instance, not featuring cigarettes/cigars and the liquors in the sets? |

|

Purpose of platform |

Deliberating and debating the purpose of the platform |

Why not take some small losses in the name of fun and engagement? Because they are a for-profit business. Making money is their primary purpose. They are all for fun and engagement, but only if they can make a profit doing it. |

|

Justice |

Deliberating and debating the fairness of the outcomes for particular sets |

Still think it is crap the corvette didn’t get picked. That was an awesome model and they have nothing right now that compares. I’m not burying a big technic car. I don’t like vws or minis. How about something for a sports car enthusiast that isn’t a super car? They even have a license deal with GM. Wtf!? |

|

Which models |

Deliberating and debating the merits of a proposed model. This differs from evaluating in that rather than offering a set evaluation, the poster seeks to start an open ended discussion of the merits and faults of a propsed kit. As such, it might result in evaluating. |

While I agree with some of these new guidelines, they leave a lot of overlooked details, as well as inconveniences and problems. First of all I suggest they remove the piece limit, as Lego has, on several occasions, made official sets with 3000-6000 pieces. these include; 2 Death stars, UCS Star Executor, UCS Millenium falcon, Taj Mahal, UCS merry go round and others. |

|

Additions to platform |

Deliberating and debating potential additions to the platform |

How about we all ask Lego Ideas for a Creators Forum where we can exchange tips and ideas? We could all send them an email. There’s been a lot of discussion happening recently within some of the comments about what’s appropriate/not appropriate, how to get more supporters, how to do good renderings, etc, and that would work WAY better if Ideas had a forum. (I know of a few external places, but that’s not the same and not everyone participates in each one) |

|

Social Networking |

Documenting |

As defined by Schau, Muñiz and Arnould (2009), detailing the brand relationship journey in a narrative way anchored by and peppered with milestones. Here it includes efforts at relaying facts and information. |

Think this is the project you are talking about: 1966 Batmobile 50th Anniversary-https://ideas.lego.com/projects/63116 Archived due to overlap with 76052 Batman™ Classic TV Series – Batcave |

Social Networking |

Evaluating |

Offering critiques of user submitted kits, offering critiques of other comments on kits. |

But theres just so much of it that it drowns out everything else on Ideas. |

Social Networking |

Milestoning |

As defined by Schau, Muñiz and Arnould (2009), noting seminal events in brand ownership and consumption, it operates a little differently in this context. LEGO created several milestones for submitted projects. At 1,000 votes, a submission can no longer be deleted. At 5,000 votes, a project gets an additional six months to reach 10,000 votes. At 10,000 votes, the project is submitted for internal review |

Congratulations on 5,000 supporters! You’ve earned an extra 182 days. Wow! By passing 5,000 supporters, you’ve made it into the upper ranks on LEGO Ideas. Since you’ve passed the halfway point, here’s another 6 months (182 days) to reach the final milestone of 10,000 supporters. Best of luck as you aim to finish your journey strong.Contributors have accepted the value of these milestones and work toward them and congratulate others on reaching them |

Social Networking |

Supporting |

Related to what Schau, Muñiz and Arnould (2009) called empathizing: Lending emotional and/or physical support to other members, including support for brand-related trials (e.g., product failure, customizing) and/or for non-brand-related life issues (e.g., illness, death, job). |

I’ve been meaning to write something like this for a while. You’ve totally hit the nail on the head. At least 50% of what gets 10k votes has no chance of ever being made and it’s a complete waste of everyone’s time. |

Figure 26.1 Cocreation practice process (adapted from Barley and Tolbert, 1997)

Practices are dynamic and follow a certain trajectory as they are enacted (Boulaire and Cova 2013; Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould 2009; Warde 2005). We found evidence of 13 practices. Two (documenting and milestoning) were identified previously by Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009) in their list of 12 practices. Another, supporting practice was similar to their practice of empathizing. One was similar to what Skålén, Pace, and Cova (2015) term questioning and answering. The other nine practices were new practices that we discerned in this context. We validated practices proposed by Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009) and Skålén, Pace, and Cova (2015) but discovered that neither of these extant typologies fully captured the complex reality of the interactions herein. One user practice stands out for its frequency, and because it has not been documented in the extant literature; we labeled it as “deliberating.” Deliberating involves contributing to a collective problem-solving exercise, whether it is about crafting new rules, finding solutions to a dilemma, questioning fairness, or establishing purpose.

On LEGO Ideas, practices are authored by various actors at differing levels of aggregation and occupying diverse roles with respect to the brand and the market. We documented posts by two LEGO Ideas administrators, one of whom has a particularly strong reputation among fans. Other posts were by long-term fans whose reputation and influence are apparent. Some posts are the work of one-time participants who want to weigh in on a relevant topic. Others can be found repeatedly opining on one topic or another. Here, we note that the idea of a single brand community centered on the brand (Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould 2009; Skålén, Pace, and Cova 2015) obscures a great deal of community diversity and detail. There is not just one LEGO brand community; there are myriad collectives, temporary ad hoc communities that form and then dissolve, enduring tribes, and subcultures all interacting to create and realize value in the LEGO ecosystem. As a result, the landscape of participants on the LEGO Ideas platform is fragmented and complex. Whereas most participants are probably members of one or more LEGO-related communities, there is no one fan community specifically tied to the LEGO Ideas platform. Coupled with the lack of a LEGO Ideas forum per se (users can only comment on proposed models and in response to official LEGO Ideas blog posts), this fragmentation makes for an interesting paradox: on the one hand, users are acting independently; on the other hand, some have the power of strong fan communities behind them. This is an important consideration in our analysis.

Because our main purpose is to explore the institutional effects of interactions between the firm and consumers from a process perspective, we follow the lead of relevant extant literature. Channeling Warde (2005), Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009) note that practices have trajectories, that is, a history and path of development. They are socially constructed (Warde 2005) and evolve toward greater institutionalization. As Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009) note, practices that begin informally (e.g., creating Xena cosplay costumes) can evolve from simple actions (repurposing found items of clothing to fashion a crude outfit resembling a character) into complex actions (creating from scratch elaborate creative efforts that stress increasing levels of accuracy and professionalism). Their socially constructed nature makes these trajectories both autonomous from direct management efforts and indirectly responsive to management practices and the strategy they reflect. While the trajectory of these practices can be indirectly affected by individual or collective decisions (e.g., whether to allow a dialogue on the platform), they are the by-product, rather than the deliberate outcome, of the social processes of cocreation. As such, these trajectories could either create problems for firm/consumer cocreation or foster ever greater efficiency and harmony in the cocreation process. In the context of LEGO Ideas, we observed a clear evolution in the degrees and types of creativity on display, with both outcomes (increased friction and increased harmony in the cocreation process) resulting.

Figure 26.1 represents the time line from the inception of LEGO Ideas to June 2016, when a new set of guidelines was announced on the platform. We treated each of the identified phases as a specific event that included both an initial post and the conversation that ensued, either among fans or, at times, between fans and the LEGO Ideas administrators. While the administrators often do not actively engage in these conversations, their presence is strongly felt in several ways: they are often addressed or mentioned directly, and their selective responses are meaningful. By responding only to very specific questions, the administrators are clearly communicating their policy not to participate in broader conversations.

The sequential analysis reveals three overall trajectories in the practices of fans. First, fans gradually shift their deliberations more toward each other rather than the administrators. Together, the fans in the community consider issues such as how the platform should evolve. Second, fans gradually tend to address more strategic issues. They shift their concerns from evaluating particular proposed models to discussing how the LEGO Group should use the LEGO Ideas platform. Third, fans gradually exhibit greater evidence of appropriation—that is, they increasingly view the platform, and the contributions it yields, as theirs.

At the same time, our analysis of the two administrators shows three general responses. First, administrators gradually engage less in general conversations about the platform and its strategy. Over time, official comments shift toward specific models and particular posting rules rather than the platform itself. Second, administrators tend to respond only to very specific and direct questions. Over time, responses focus less on general issues and more on very discrete ones. Third, administrators strongly favor responding to model-specific questions.

These actions suggest that the two institutions of fans and administrators are evolving in opposite directions; whether this phenomenon is causal, however, is unclear. Our sequential analysis is based on Barley and Tolbert’s (1997) methodology, but it exhibits one crucial difference from their study—namely, we work across different institutions, the firm, and its fans. We suggest that users of the LEGO Ideas forum do not start out with much of an institutional logic and are, at first, loosely organized, if at all. Our claim is that through their interactions on the LEGO Ideas platform, fans form institutional bonds with one another. In other words, over time, an institution centered on LEGO Ideas forms among fans who follow and contribute to LEGO Ideas. Their discursive interactions (Phillips, Lawrence, and Hardy 2004) among themselves and with the LEGO Ideas platform and its administrators shape their practices. Effectively, then, we are demonstrating the institutionalization process that takes place through the actions and interactions of platform users and administrators.

A relevant point on this trajectory also comes from Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009), who note that practices endow participants with cultural capital. In the context of LEGO Ideas, the adroit performance of practices is a way for participants to claim status and have their voices heard. This could explain the drive toward increasingly complex and creative designs and greater deliberation. The competitive game surrounding the accrual of field-specific cultural capital can lead to a one-upmanship or ratchetting of efforts. This might explain a trend we have observed toward increasingly elaborate kits proposed on LEGO Ideas. Larger and more elaborate models are becoming more common. Members may be creating and submitting these increasingly sophisticated models as a way to compete with and top those that came before them, rather than creating models that LEGO can effectively sell to the mass market. This tendency seems to be a powerful driver in the movement to revise the platform rules, as some communities’ members recognize the tendency toward overcomplexity and resent it.

The adroit performance of practices is also a way of being heard, appropriating the space, and even staking a claim as a cobuilding partner. The fans are becoming increasingly vocal. The LEGO Group is also evolving in its practices (stated formally in its terms of service) to balance community preferences and practices with firm goals and practices. In the two-and-a-half years that LEGO Ideas has been running, the terms of service and guidelines have been revised multiple times. The most recent revision appears to respond to recent calls from the community.

Deliberating the Rules and Purpose of the Platform

One of the phases we identified functioned as a precipitating event in the deliberations over the rules and purpose of the LEGO Ideas platform. In late January 2016, a user proposed a model featuring a life-sized replica of the Star Wars robot R2D2. As an extreme instance of the trend toward larger and more complex models, this event triggered deliberation among LEGO Ideas followers and participants. The discussion on the proposed model’s LEGO Ideas page and a resulting off-site (Reddit.com) thread contribute to the three-pronged trajectories we described previously of increased deliberation, increased appropriation, and increased focus on strategy by fans. These discussions also represent a very real and sincere effort by fans to determine the purpose and rules of the site, including the best strategy for LEGO to follow. These threads represent an increased sense of appropriation of the site by fans.

Considering its size, the proposed R2D2 model would consist of thousands of bricks, it would be very expensive to package and ship, and consequently it would be impractical for most consumers. The designer recognizes this in his posting about the model (contributing practice):

The Kenny Baker Artoo is about 16,000 bricks. Wow! Think about that when supporting, it’s not going to be cheap. This will be the most expensive LEGO set by far, but we all know how much fans want this set. Don’t hesitate to sell your car (or at least your spouse’s car) droids are better! The only way we have to let LEGO know that we’re willing to buy sets of this scale is to share like mad and get 10K supporters faster than any project has ever done. We can do it! Even so, it’s likely going to have to be a very limited edition (& premium) run.

The creator of the proposed model knew it would be impractical and expensive but also believes that there is some real fan demand for such an elaborate model.

This model produced polarized reactions in the LEGO Ideas comments accompanying the proposal: users either loved the model (“supporting” practice) or challenged its viability and appropriateness (“challenging” practice). As one poster opined, “This, in its current size, will never be approved. The price would be outrageous. If it gains 10,000 votes, only a fraction of the supporters would ever be able to buy it. LEGO Ideas isn’t intended to cater to niche markets. The design is incredible and stunning. However, this is the wrong platform to showcase it.” Another poster summed up the naysayers’ position as follows: “It’s not going to happen, ever. This IDEAS platform seems to support the spread of false hopes.” Around the same time, this poster also initiated an off-platform discussion on Reddit that was highly critical of the current state of the LEGO Ideas platform and proposed sweeping guideline changes.

As the discussion about this proposed model continued, posters linked to other examples of indulgent, high-brick-count models, essentially “documenting” other excesses. The R2D2 model was viewed as symptomatic of a few broad trends. As one contributor posted,

I agree, something needs to be done. There should at least be a preliminary [evaluation to determine] ‘Is this even an idea’ step done by LEGO … I’ve seen some over the top submissions but I didn’t even realize that lord of the rings [sic] one even existed. How does the person ever expect to get that approved? How would anyone even begin to make instructions for that thing? … I just looked at the actual updates for the Rivendell one. The actual set is just 7 buildings and not his giant diorama? That seems super deceptive. The pictures should only be what he includes in the set.

Here, the poster is “deliberating” both the rules of the game and the purpose of the site. The Lord of the Rings set mentioned in this post is similarly large and complex, and the poster is taking issue with it. There is some similarity to previously documented practices of “governing” and “managing” (Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould 2009; Skålén, Cova, and Pace 2015), but here, the governing and managing are debated by users on behalf of LEGO.

Despite acknowledging its impracticality, the R2D2 designer is sincere in wanting to send a message to LEGO that fans are interested in larger models. In this way, he is actively engaging in the “challenging” practice. He responded defensively to questions by commenters regarding its impracticality.

Thanks for supporting anyway! I don’t subscribe to the ‘LEGO will never make a different UCS model on the same theme’ view. The UCS Artoo was pretty small—besides it wasn’t a Kenny Baker one :)—Besides they could just coin a new term/series if they wanted ‘Limited Edition Collectible’ or whatever. That aside, this one’s going to be a serious challenge for them.

Here, the designer is justifying his model relative to other models produced by the LEGO Group while recognizing the difficulty his model would present. This reaction only served to energize opponents of his model and the trend they felt it represented. The critical conversation moved off-site.

One of the more critical contributors to the R2D2 discussion simultaneously initiated a Reddit discussion titled “LEGO Ideas Sucks Right Now.” This thread was noteworthy for several reasons. It was initiated off-site because LEGO Ideas does not include an open forum. It also demonstrates the propensity of the users to think and reason (“deliberating”) on behalf of LEGO more prominently than in the R2D2 thread. The creator of this thread begins his first post with the following:

LEGO Ideas is a wonderful idea, giving fans a chance of getting their own set into production. However, LEGO is backing themselves into a corner with how things are going. This ‘everyone is a special little snowflake’ attitude that is widespread in the site shouldn’t be there, it let’s people post almost anything on the site. It has gone to the point where if you post actual valid criticism, stating facts such as “this set already exists” and “this is the size of a LEGOLAND display piece,” people will call you a hater and threaten you by saying you will get banned or flagged with that attitude … People seem to have forgotten that the platform is a place where you pretty much put up an essay to get your submission onto store shelves. Now it’s like a forum to post your builds (whatever they are), and humongous MOCs [My Own Creation, designating user-created LEGO models]. LEGO.com and other forums are for that kind of stuff, not LEGO IDEAS.

Multiple practices are evident in this quote, including “challenging,” “contributing,” and “deliberating.” The user wants LEGO Ideas to thrive and the LEGO Group to succeed as a business. His critique of rules, operation, and purpose is intended to be collaborative.

The post goes on to deliberate the rules and purpose of the platform and to offer some possible solutions:

So what the heck can we do about this? Here’s 3 things that should be done: -1- Put some actual quality control on the submission page. Besides the obvious stuff, you can post ANYTHING if the picture meets the guidelines. Stuff like this happens often, not as bad, but to a certain degree. -2- Implement a size limit. I can’t stress this enough, look at this and this, and tell me with a straight face that these have a chance. Do they look awesome? Yes. Would I like to have one? Yes. Will I get one? Probably not. When you click support, you get possible price options for: | 10$-49$ | 50$-99$ | 100$-199$ | +200$ | I think it should look a bit more like this: | 10$-40$ | 40$-70$ | 70$-100$ | +100$ | -3- Prohibit submissions from current licences LEGO is using. This goes along nicely with 2#, because there is so much stuff, mostly from Star Wars that is just HUGE, and even if they weren’t huge, If they have a licence, and you suggest something from that licence, chance is they have a prototype/project for it, and suggesting a possible set already in development isn’t going to take you far. It hasn’t worked so far for any LEGO Ideas project, and it will never work.

This poster is proposing new rules and procedures and clarifying the role of LEGO Ideas for both LEGO and users. He is fully supportive of LEGO’s commercial motives, and his proposed changes aim to eliminate the most common problematic elements.

This thread produced a vigorous conversation with more than 200 comments over the course of two weeks. Most comments are surprisingly supportive of LEGO’s efforts to encourage product marketability. This is interesting because it is at odds with the distancing-from-the-market practice that Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009) describe. One responder wrote the following, evincing the “supporting” practice:

Reading all this ranting and arguing makes my soup [sic] feel good! I agree that Ideas needs to be overhauled again. All the crap is keeping the real good ideas from being made. And it should be clear to people now what kind of sets will get made: ones that there is a substantial market for, ones that are between $20-$70 and between 200–700 pieces, and ones that don’t interfere with license that LEGO already holds (no star wars, super heroes, or lotr). Also if your idea is for a non-licensed set and it meets all the criteria I just listed, then you will have even better chances. All this seems so obvious to me. How is everyone having such a hard time not realizing that they won’t make a $600 sandcrawler or $1000 Rivendell? Or that, much as I would love one, they will not make a Legend of Zelda set! People just need to be more original with their submissions.

The poster proposes criteria consistent with ensuring the LEGO Group’s success and expresses amazement that all participants do not understand these criteria. This posting was not atypical. Most contributors to this thread expressed similar views.

Appropriation and Official Response

The conversations excerpted here show fans engaging in sophisticated deliberation over questions such as product relevance, marketability, positioning, community strategy, and more. Fans are claiming their role as comanagers of LEGO Ideas and want to appropriate the space (Visconti et al. 2010). Their practices indicate increasing appropriation of the process and its rules, an increasing focus on the rules of the game, the purpose of the platform, and the modes of communication. In other words, through their deliberative practices, fans are increasingly asking for a “way in,” for an opportunity to participate in a democratic process.

This finding echoes the work of Visconti et al. (2010), in that appropriation can take the form of either a dialectical or a dialogical process, depending on the individualist or collectivist appraisal each group of stakeholders has of the space. In the case of LEGO Ideas, we observe a collectivist appraisal by most of the fans who contribute and a somewhat ambivalent appraisal by LEGO Ideas administrators. While the very premise of the platform as a place of cocreation is collectivist, many of the administrator posts we analyzed are more individualist in nature. When the administrators provide clarifications or support, they tend to prefer addressing individual members; they discourage broad conversations. Indeed, such preference is built into the system. The platform does not provide a forum but rather a blog on which all conversations are initiated by administrators. By virtue of these actions, LEGO Ideas is managed primarily by its administrators as a platform on which individual fans interact with LEGO by submitting projects. Even the voting process constitutes an individual exercise in “representational democracy” rather than in the collective exercise of “deliberative democracy” (Guttman and Thompson 2004; Ozanne, Corus, and Saatcioglu 2009) that the users are trying to implement.

LEGO has adjusted its terms of service and site guidelines for LEGO Ideas several times over the course of its existence. In addition, both the terms of service and the guidelines changed from those used by the predecessor to LEGO Ideas, LEGO Cuusoo, a crowdsourcing experiment that ran from 2008 to April 2014 (LEGO Ideas Blog 2014). The terms of service and the guidelines for LEGO Ideas were designed with feedback from the Cuusoo experiment in mind. The greatest changes were giving projects one year to reach 10,000 supporters, extending submission eligibility to contributors ages 13–18 years, creating Clutch Power points (which facilitated the practices of milestoning and badging [Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould 2009]), eliminating edits after submission, and disallowing mock-ups of LEGO product boxes. Reactions to these changes were mostly positive, with most commenters trying to clarify their understanding of the new rules.

The most recent changes, announced in June 2016, nearly six months after the R2D2 and Reddit threads, represented the largest set of changes ever to the LEGO Ideas guidelines and its terms of service and closely reflected some of the changes advocated by community members in those threads. The principal change sought, in congruence with the Reddit thread, was to limit “submissions from current licenses LEGO is using.” Because many commenters had responded positively to this suggestion, this is perhaps not surprising. Changes also included a limit of 3,000 pieces per model, consistent with user suggestions to “implement a size limit.” Again, many commenters, on both the Reddit and the R2D2 threads, responded affirmatively to this suggestion, focusing on cost/price considerations.

Discussion and Conclusion

We have demonstrated clear evidence of institutionalization processes through practice trajectories that are themselves tied to the collaborative processes among fans and with the firm. Fans want in. They contribute a wide range of resources and are increasingly claiming a piece of the public space and an opportunity for democratic deliberation. However, while our time line starts at the inception of LEGO Ideas, we cannot ignore the overall context of a brand with a historically highly engaged and broad ecosystem.

A crucial aspect of the practice trajectories we have documented is users’ increasing focus on clarifying the purpose of the platform. This is appropriation gone strategic. Users deliberate issues such as pricing, go-to-market strategy, and licensing, virtually usurping the role of LEGO senior marketers. For LEGO and its LEGO Ideas team, this strategic appropriation process poses its own crucial strategic challenges. As fans engage in more deliberative practices, should LEGO embrace the democratic deliberative processes or maintain the platform’s more traditional mode of participation?

In the context of public policy management, a distinction has been made between two dimensions of public engagement: participation and inclusion (Quick and Feldman 2011). Participatory practices involve accessing a broad range of inputs, whereas inclusive practices facilitate the diversity and the strategic nature of inputs. In particular, inclusive practices exhibit three characteristics: they allow “different ways of knowing” (to include diverse participants), they “coproduce the process and content of decision making” (thereby adding strategic input), and they acknowledge “temporal openness” (accepting the long-term involvement of the community in a process that will continue to evolve over time) (Quick and Feldman 2011, 282). A comparative study of four public management projects with high/low participatory practices and high/low inclusive practices found that the highest levels of participant satisfaction were experienced under high-inclusive-practice conditions, with high participation scoring higher than low participation (Quick and Feldman 2011). While the public management study does not address the question of institutionalization, we can assume that the three facets of inclusive practices are conducive to institutionalization.

Our findings suggest that involvement at a strategic level not only meets user expectations but also may be beneficial in terms of customer satisfaction. While LEGO Ideas administrators refrain from explicit deliberation, we observe that they are both very attuned and responsive to fan deliberations, particularly when it comes to more strategic matters such as guidelines. As such, we could see a pattern develop in which fans continue to deliberate publicly until they get the attention of administrators. Fans make their case over time, patiently, with no real validation by LEGO, and then one day, a change is posted that addresses some of their points. They understand that LEGO operates according to a certain corporate machinery, and they simply try to find ways to make their case over time.

The issue is a broader one from simply a strategic perspective. Scholars have noted concerns about the fairness of cocreation. Cova, Pace, and Skålén (2015) consider two perspectives on consumer involvement and cocreation. One perspective views cocreating consumers as empowered and enabled in their efforts—it is a good thing because consumers are liberated. The critical perspective views cocreating consumers as being shaped and disciplined through marketing discourses—in this view, cocreating consumers are being exploited. We side with the former perspective because we consider the actions of appropriation evidence of awareness and agency. We believe that the critical perspective still relies on the trope of the consumer as a cultural dupe. It presupposes no self-awareness at either the individual or the institutional level, and it fails to take into account the very effects of institutionalization we have documented here.

In their work on community-embedded creative consumers, Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009) suggest that future research should attempt to discern and unpack the operation of a broader set of practices. Refining such understandings, they assert, will prove useful in creating novel strategies to further leverage the creative tendencies of marketplace actors. We have responded to this call and proposed inclusion as a novel strategy. While we validated the practices proposed in Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009) and Skålén, Pace, and Cova (2015), we also discovered that neither of these two extant typologies fully captures the complex reality of the interactions on the LEGO Ideas platform at this moment in time. This may reflect a reality that the identification of practices is an inherently idiosyncratic affair in which new contexts will require the divination of new practices.

Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009, 41) also assert that “ceding control to customers enhances consumer engagement and builds brand equity.” However, we believe that there is more complexity to this. Not only are the practices of the firm and consumers different, but crucially, they are constantly changing as well. In other words, understanding practices is simply not enough. As institutional logics develop between a firm and its customers, some level of appropriation on the part of customers is to be expected. The question for firms is whether they want to get ahead of the curve by adopting the collectivist, inclusive practices we have discussed. In either case, firms probably have much to gain from being transparent about some key strategic elements: the purpose of the cocreation activities or platform (e.g., product development, market research, customer engagement) and the degree and limits of customer involvement they are seeking. Acknowledging that these parameters may evolve would also be a positive signal.

Terwiesch and Xu (2008) note that one of the largest challenges in cocreation is designing appropriate interface mechanisms. Füller, Hutter, and Faullant (2011) and Singh (2014) similarly assert that another challenge is managing the process. We echo these concerns and unpack them. Managing the process involves establishing rules and expectations. We contend that a formidable approach would be to adopt the inclusive practices of public management by jointly and continually deliberating these points. This does not mean that the firm should abandon its goals or principles or, conversely, that members of the community should expect total and complete control. What we observe on the LEGO Ideas platform are highly appreciative and business-minded customers who have the best interest of the brand at heart; they are stakeholders in the truest sense. Of course, there are also risks: Schau, Muñiz, and Arnould (2009) assert that marketers should encourage greater diversity in practice. We agree, but with the following caveat: Be careful what you wish for. A proliferation of practices does not guarantee that the practices will be desirable to or compatible with the marketer.

References

Antorini, Yun Mi. 2007. “Brand Community Innovation: An Intrinsic Case Study.” Doctoral dissertation, Department of Innovation and Organizational Economics, Copenhagen Business School.

Antorini, Yun Mi, Albert M. Muñiz Jr., and Tormod Askildsen. 2012. “Collaborating with Customer Communities: Lessons from the LEGO Group.” MIT Sloan Management Review 53 (3): 73–95.

Aubert-Gamet, Véronique. 1997. “Twisting Servicescapes: Diversion of the Physical Environment in a Re-appropriation Process.” International Journal of Service Industry Management 8 (1): 26–41.

Baichtal, John, and Joe Meno. 2011. The Cult of LEGO. San Francisco: No Starch Press.

Barley, Stephen R., and Pamela S. Tolbert. 1997. “Institutionalization and Structuration: Studying the Links Between Action and Institution.” Organization Studies 18 (1): 93–117.

Bayus, Barry L. 2013. “Crowdsourcing New Product Ideas over Time: An Analysis of the Dell IdeaStorm Community.” Management Science 59 (1): 226–44.

440Boulaire, Christèle, and Bernard Cova. 2013. “The Dynamics and Trajectory of Creative Consumption Practices as Revealed by the Postmodern Game of Geocaching.” Consumption Markets & Culture 16 (1): 1–24.

Chanal, Valérie, and Marie-Laurence Caron-Fasan. 2010. “The Difficulties Involved in Developing Business Models Open to Innovation Communities: The Case of a Crowdsourcing Platform.” M@n@gement 13 (4): 318–40.

Cova, Bernard, Stefano Pace, and Per Skålén. 2015. “Brand Volunteering Value Co-creation with Unpaid Consumers.” Marketing Theory 15 (4): 465–85.

Crowdsourcing.org. 2013. “Genius Crowds Closes Its Doors,” accessed March 30, 2016, www.crowdsourcing.org/editorial/genius-crowds-closes-its-doors/25946.

Epp, Amber M., and Linda L. Price. 2011. “Designing Solutions Around Customer Network Identity Goals.” Journal of Marketing 75 (2): 36–54.

Feldman, Martha S. 2004. “Resources in Emerging Structures and Processes of Change.” Organization Science 15 (3): 295–309.

Filieri, Raffaele. 2013. “Consumer Co-creation and New Product Fevelopment.” Marketing Intelligence & Planning 31 (1): 40–53.

Friedland, Roger, and Robert R. Alford. 1991. “Bringing Society Back In: Symbols, Practices and Institutional Contradictions.” In The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, edited by W. W. Powell & P. H. DiMaggio, 232–63. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Füller, Johann, Katja Hutter, and Rita Faullant. 2011. “Why Co-Creation Experience Matters? Creative Experience and Its Impact on the Quantity and Quality of Creative Contributions.” R&D Management 41 (3): 259–73.

Füller, Johann, Hans Mühlbacher, Kurt Matzler, and Gregor Jawecki. 2009. “Consumer Empowerment Through Internet-Based Co-Creation.” Journal of Management Information Systems 26 (3): 71–102.

Gebauer, Johannes, Johann Füller, and Roland Pezzei. 2013. “The Dark and the Bright Side of Co-Creation: Triggers of Member Behavior in Online Innovation Communities.” Journal of Business Research, 66 (9): 1516–27.

Gloor, Peter, and Scott Cooper. 2007. “The New Principles of a Swarm Business.” MIT Sloan Management Review 48 (3): 81–84.

Guttman, Amy, and Dennis Thompson. 2004. Why Deliberative Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hartmann, Benjamin J., Caroline Wiertz, and Eric J. Arnould. 2015. “Exploring Consumptive Moments of Value-Creating Practice in Online Community.” Psychology & Marketing 32 (3): 319–40.

Healy, Jason C., and Pierre McDonagh 2013. “Consumer Roles in Brand Culture and Value Co-creation in Virtual Communities.” Journal of Business Research 66 (9): 1528–40.

Hienerth, Christoph, Christopher Lettl, and Peter Keinz. 2014. “Synergies Among Producer Firms, Lead Users, and User Communities.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 31 (4): 848–66.

Jeppesen, Lars Bo, and Karim R. Lakhani. 2010. “Marginality and Problem-Solving Effectiveness in Broadcast Search.” Organization Science 21 (5): 1016–33.

Koerner, Brendan I. 2006. “Geeks in Toyland.” Wired (February 1): 104.

Kozinets, Robert V. 2002. “Can Consumers Escape the Market? Emancipatory Illuminations from Burning Man.” Journal of Consumer Research 29 (1): 20–38.

Kozinets, Robert V., Andrea Hemetsberger, and Hope Jensen Schau. 2008. “The Wisdom of Consumer Crowds Collective Innovation in the Age of Networked Marketing.” Journal of Macromarketing 28 (4): 339–54.

Kozinets, Robert V., Kristine De Valck, Andrea C. Wojnicki, and Sarah J. S. Wilner. 2010. “Networked Narratives: Understanding Word-of-Mouth Marketing in Online Communities.” Journal of Marketing 74 (2): 71–89.

Lawrence, Thomas B., Cynthia Hardy, and Nelson Phillips. 2002. “Institutional Effects of Interorganizational Collaboration.” Academy of Management Journal 45 (1): 281–90.

LEGO Ideas Blog. 2014. “Welcome to LEGO Ideas!,” accessed June 2016, https://ideas.LEGO.com/blogs/1-blog/post/1.

McAlexander, James H., John W. Schouten, and Harold F. Koenig. 2002. “Building Brand Community.” Journal of Marketing 66 (1): 38–54.

Muñiz, Albert M., Jr., and Thomas C. O’Guinn. 2001. “Brand Community.” Journal of Consumer Research 27 (4): 412–32.

Muñiz, Albert M., Jr., and Hope Jensen Schau. 2005. “Religiosity in the Abandoned Apple Newton Brand Community.” Journal of Consumer Research 31 (4): 737–47.

441Muñiz, Albert M., Jr., and Hope Jensen Schau. 2007. “Vigilante Marketing and Consumer-Created Communications.” Journal of Advertising 36 (3): 35–50.

Muñiz, Albert M., Jr., and Hope Jensen Schau. 2011. “How to Inspire Value-Laden Collaborative Consumer-Generated Content.” Business Horizons 54 (3): 209–17.

O’Hern, M., and Aric Rindfleisch. 2010. “Customer Co-Creation,” in Review of Marketing Research, edited by Naresh K. Malhotra, 84–106. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Ozanne, Julie L., Canan Corus, and Bige Saatcioglu. 2009. “The Philosophy and Methods of Deliberative Democracy.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 28 (1): 29–40.

Payne, Adrian F., Kaj Storbacka, and Pennie Frow. 2008. “Managing the Co-creation of Value.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 36 (1): 83–96.

Phillips, J. 2011. “Open Innovation Typology.” in A Guide to Open Innovation and Crowdsourcing, edited by P. Sloane, 22–35. London: Kogan Page.

Phillips, Nelson, Thomas B. Lawrence, and Cynthia Hardy. 2004. “Discourse and Institutions.” Academy of Management Review 29 (4): 635–52.

Quick, Kathryn S., and Martha S. Feldman. 2011. “Distinguishing Participation and Inclusion.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 31 (3): 272–90.

Rivkin, Jan W., Stefan H. Thomke, and Daniela Beyersdorfer. 2013. “LEGO (A): The Crisis.” Harvard Business School Case 713–478, February 2013.

Robertson, David, and Bill Breen. 2013. Brick by Brick: How LEGO Rewrote the Rules of Innovation and Conquered the Global Toy Industry. New York: Crown Business.

Schau, Hope Jensen, Albert M. Muñiz Jr., and Eric J. Arnould. 2009. “How Brand Community Practices Create Value.” Journal of Marketing 73 (5): 30–51.

Singh, Narinder. 2014. “Crowdsourcing in 2014: With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility,” Wired (January): www.wired.com/insights/2014/01/crowdsourcing-2014-great-power-comes-great-responsibility/.

Skålén, Per, Stefano Pace, and Bernard Cova. 2015. “Firm-Brand Community Value Co-Creation as Alignment of Practices.” European Journal of Marketing 49 (3–4): 596–20.

Taillard, M., L. D. Peters, J. Pels, & C. Mele. 2016. “The Role of Shared Intentions in the Emergence of Service Ecosystems.” Journal of Business Research 69 (8): 2972–80.

Terwiesch, Christian, and Yi Xu. 2008. “Innovation Contests, Open Innovation, and Multiagent Problem Solving.” Management Science 54 (9): 1529–43.

Visconti, Luca M., John F. Sherry, Stefania Borghini, and Laurel Anderson. 2010. “Street Art, Sweet Art? Reclaiming the ‘Public’ in Public Place.” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (3): 511–29.

Von Hippel, Eric A. 2005. Democratizing Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press Books.

Warde, Alan. 2005. “Consumption and Theories of Practice.” Journal of Consumer Culture, 5 (2): 131–53.

Weingarten, Mark. 2007. “‘Project Runway’ for the T-shirt Crowd.” CNN Business 2.0 (June 18), accessed December 2016, http://money.cnn.com/magazines/business2/business2_archive/2007/06/01/100050978/index.htm?postversion=2007061806