MULTIPLE SHADES OF CULTURE: INSIGHTS FROM EXPERIMENTAL CONSUMER RESEARCH

1COLLEGE OF ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCES AND ECONOMICS AT KOÇ UNIVERSITY, ISTANBUL, TURKEY

2MARKETING DEPARTMENT AT BOCCONI UNIVERSITY, MILAN, ITALY

Even if you don’t like colors, you will end up having something red. For everyone who doesn’t like color, red is a symbol of a lot of culture. It has a different signification but never a bad one.

Christian Loubotin

In the past couple of decades, research investigating the role of culture on consumer preferences and choices has gained increased attention. It is important to investigate the role of culture as culture influences perception, behavior, inter-personal communication, and relations, and even helps one to develop a personality. It influences one’s way of thinking and living. With art, literature, language, and many other aspects, culture provides meaning to individuals. Hence, understanding the effects of culture on consumer behavior is important as it helps one to understand how different meaning makers in different cultures might influence the way consumers behave in the marketplace.

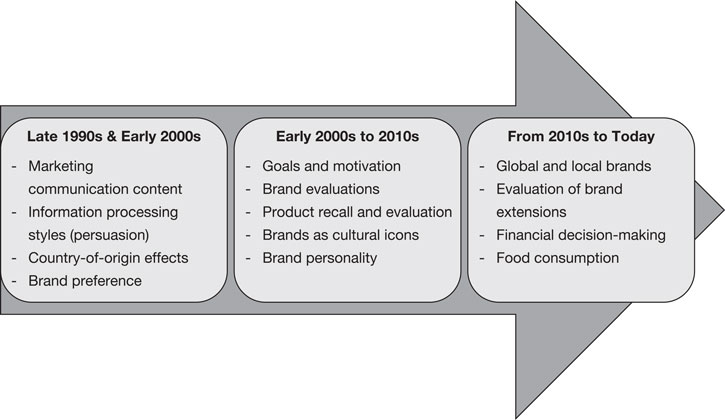

Our goal in this chapter is to provide a timeline for cross-cultural consumer research. We specifically suggest that cross-cultural consumer research has gone through three stages: (1) the introduction stage during the late 1990s, (2) a growth stage in the early 2000s, and (3) the maturity stage in the early 2010s. Acknowledging that there have been many different methods used to investigate the effects of culture on consumer behavior (e.g., qualitative research), in this chapter we only focus on experimental research conducted in these three time phases and suggest that there is still a lot of room for future research to investigate how culture might influence consumer preferences and choices.

Timeline of Cross-Cultural Consumer Research

Culture and Consumer Behavior Research in the

Late 1990s and Early 2000s

In reviewing the literature on culture and its influences on consumer behavior, it is important to emphasize research that has been conducted by Hofstede (1984) and Triandis and Gelfand (1998). In his influential work, Hofstede (1984) analyzed a database of employee value scores in IBM between 1967 and 1973. Analyzing data that covered more than 70 countries, he categorized country cultures based on four groups: power distance (i.e., the extent to which power is distributed unequally), individualism versus collectivism (i.e., the extent to which people in a society are integrated into groups), masculinity versus femininity (i.e., the extent to which there is a preference for achievement, assertiveness, material rewards for success or preference for cooperation, modesty), and uncertainty avoidance (i.e., the extent to which society has a tolerance for ambiguity). He named these four dimensions the dimensions of national culture, where each national culture would differ on these four different parameters. Although there have been additions to these dimensions (e.g., long-term orientation, indulgence versus restraint) in subsequent years, with more than 30,000 citations, Hofstede’s work still remains one of the most influential frameworks for cultural researchers.

Furthermore, Triandis and Gelfand (1998) distinguished four dimensions of individualism and collectivism (i.e., vertical individualism, horizontal individualism, vertical collectivism, and vertical individualism). They defined vertical individualism as seeing the self as fully autonomous, but acknowledging there are inequalities that exist among individuals, while they have defined horizontal individualism as seeing the self as fully autonomous but believing that equality between individuals is the ideal. On the other hand, they have defined vertical collectivism as seeing the self as a part of a group but recognizing that there are inequalities within that group, while they have defined horizontal collectivism as seeing the self as a part of a group but believing that everybody in a group has equal rights. Hence, they have distinguished among different cultures on two dimensions: (1) whether people perceive themselves as part of a group or as being autonomous and (2) whether people acknowledge inequalities or they perceive everybody as equal. Distinguishing among vertical and horizontal individualism/collectivism, Triandis and Gelfand (1998) lead individuals in social psychology to investigate differences among different cultures.

Despite the growing interest in cross-cultural psychology in the 1990s with these two frameworks, relatively little was known about the processes by which culture affects consumer behavior. The literature that investigated the effects of culture was based on frameworks developed using participants from Western cultures, primarily the ones from the United States (Gergen, Gulerce, Lock, & Misra, 1996). In the late 1990s and early 2000s, researchers in consumer psychology started to pay attention to the effects of culture on consumer behavior (Aaker & Maheswaran, 1997; Maheswaran & Shavitt, 2000; Gürhan-Canli & Maheswaran, 2000). In this section, we review the early empirical work on culture and consumer behavior that began in the late 1990s. We suggest that most of the earlier work primarily focused on: (1) marketing communication content that would be persuasive across different cultures and (2) different information processing styles across cultures. In this section, we further demonstrate that the earlier work on cross-cultural consumer psychology mainly focused on individualism-collectivism dimensions of culture and neglected the other cultural orientations.

In one of the earliest empirical works on culture and its effect on consumer behavior, Han and Shavitt (1994) demonstrated that advertisements emphasizing individualistic benefits were more persuasive in the United States than in Korea, while advertisements emphasizing in-group benefits or family were less persuasive in the United States than they were in Korea. Following Han and Shavitt (1994), Aaker and Maheswaran (1997) investigated the effect of cultural orientation on persuasion. The authors tested the impact of motivation, congruity of persuasive communication, and the diagnosticity of heuristic cues on the processing strategies. In two studies, they demonstrated that there were cross-cultural variations in the perceived diagnosticity of heuristic cues. In their study 1, in the high-motivation and incongruent conditions, only the consensus information guided the evaluations for collectivist participants (i.e., participants from Hong Kong). In study 2, when processing new information, processing strategies adopted by individualist participants mirrored those adopted by the collectivists. This was the first evidence of how culture might influence consumer behavior through diagnosticity.

Extending the research by Aaker and Maheswaran (1997), Aaker and Williams (1998) investigated the role of emotional appeals on persuasion across cultures. Their results demonstrated that other-focused (e.g., empathy, peacefulness) emotional appeals led to more favorable attitudes for members of an individualist (i.e., participants from US) culture, while the ego-focused (e.g., pride, happiness) appeals led to more favorable attitudes for members of a collectivist (i.e., participants from China) culture. Aaker and Williams (1998) suggested that the persuasive effects found in their study 1 were due to the differences in the generation of and elaboration on a relatively novel type of thought. More specifically, because individual thoughts were more novel for the members of a collectivist culture and because collectivist thoughts were more novel for the members of individualist culture, ego-focused emotional appeals were more effective for the collectivists and other-focused emotional appeals were more effective for the individualists.

Reconciling her research on culture and consumer behavior, Aaker (2000) investigated the extent to which differences in perceived diagnosticity (vs. accessibility) that were embedded in persuasion appeals account for the attitudinal differences. More specifically, when information elaboration was low (i.e., participants were asked to spontaneously read a text and evaluate a brand), diagnosticity and accessibility were both high and this led to positive attitudes toward the brand. When instead elaboration was high (i.e., participants were asked to carefully read a text and evaluate a brand in detail), the effect of diagnosticity was high but the effect of accessibility was low and this led to negative attitudes toward the brand. Furthermore, in a series of three studies, Aaker and Sengupta (2000) demonstrated that when faced with information incongruity, consumers in an individualist culture (i.e., United States) followed an attenuation strategy (i.e., relying on the more diagnostic information and attenuating the impact of less diagnostic information), whereas consumers from a collectivist culture (i.e., Hong Kong) followed an additive strategy (i.e., pieces of information are combined to make evaluations).

While there has been some movement in understanding how culture influences consumer behavior, which was mainly in the area of persuasion, Maheswaran and Shavitt (2000) provided a research agenda in cross-cultural research. The authors discussed the fact that much of the earlier work showing the relationship between culture and consumer behavior mainly differentiated individualist versus collectivist cultures (Aaker & Maheswaran, 1997; Aaker & Williams, 1998; Han & Shavitt, 1994; Zhang & Gelb, 1996). However, they suggested that there might be other cultural categories that would deserve attention in cross-cultural research. They called attention to the distinction between societies that are horizontal (i.e., valuing equality; Sweden, Norway, Australia) and those that are vertical (i.e., emphasizing hierarchy; USA, France). They have further suggested that what was investigated up until the 2000s mostly reflected vertical forms, neglecting the horizontal cultures. Furthermore, they have suggested that there are other dimensions of cultural variation (i.e., power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity/femininity) that might explain several differences across cultures besides from individualism and collectivism.

Wang, Bristol, Mowen, and Chakraborty (2000) investigated the effects of connected versus separated advertising appeals on Chinese versus American consumers. Their results demonstrated that, while a connected advertising appeal that stressed interdependence and togetherness resulted in more favorable attitudes among Chinese and women consumers, a separated appeal resulted in more favorable attitudes among American and male consumers. This result could be also related to the gender differences in personality traits within cultures. McCrae and Terracciano (2005) have demonstrated in a study across 50 cultures that the personality traits between women and men might vary widely (e.g., women were more emotional and warm, and men were more assertive).

Although most of the earlier work on culture and consumer behavior has focused on how culture influenced information processing, Gürhan-Canli and Maheswaran (2000) extended the research on culture to country-of-origin effects. The authors showed that, in collectivist countries (e.g., Japan), evaluations for products from one’s country of origin were more positive if they were familiar with the product, despite the superiority of it. This was mediated by vertical collectivism. On the contrary, in individualist countries (e.g., the US), the product from their country of origin got higher evaluations only if it was superior and innovative. Vertical individualism only mediated favorable product evaluations from their own country of origin. Following the research by Gürhan-Canli and Maheswaran (2000), other researchers started to investigate the effect of culture on different aspects of consumer behavior.

Summarizing the earlier work of cross-cultural consumer research, one might suggest that the earlier work on the effect of culture on consumer behavior could be explained through accessibility and diagnosticity accounts.

Culture and Consumer Behavior Research from

the Early 2000s to the 2010s

The late 1990s experienced heightened interest in investigating the effect of culture on consumer behavior. While most of the research on this stream focused on how the content of the marketing communications should differ across cultures and how culture influences information processing, researchers started to get more interested in multiple methods (e.g., surveys, content-analyses) in cross-cultural research in the early 2000s, which led them to investigate different topics in consumer psychology besides information processing differences across cultures.

In this section, we review the literature on cross-cultural consumer research that was conducted between the early 2000s and 2010. We provide evidence that most of the cross-cultural consumer research in this time period focused on (1) the effects of other cultural orientations (e.g., horizontal versus vertical) on consumer behavior, (2) the effects of culture on goals and motivation, and (3) the effects of cultural orientations on brand and product evaluations as well as the development of culture-related phenomena (e.g., cultural icons). We further provide evidence that in this period, cross-cultural consumer researchers used multiple methods to test their predictions across different cultures.

In one of the earliest papers using multiple methods, Nelson and Shavitt (2002) predicted differences in achievement values across people from Denmark and the United States. Across multiple methods (i.e., qualitative interviews, surveys), people from the United States were found to be more vertically oriented than Danish people and people from Denmark were found to be more horizontally oriented than the Americans. More importantly, people from the US discussed the importance of achievement goals more frequently and evaluated achievement values more highly than Danes did.

In the beginning of the 2000s, researchers continued to understand the characteristics of different consumers across different cultures. Employing a content analysis method, Zhang and Shavitt (2003) examined 463 ads in China with respect to the cultural values emphasized in those ads. Results of the content analysis demonstrated that both modernity and individualism values predominated the ads in China. More importantly, revealing the shifting values among the Generation X, these values were more pervasive in magazine advertisements, which targeted the Chinese Generation X, than in television commercials. On the other hand, more traditional values such as collectivism were found to be more pervasive on television commercials as opposed to magazine ads.

In an attempt to understand how response styles might differ across cultures, Johnson, Kulesa, Cho, and Shavitt (2005) investigated the effects of four cultural orientations identified by Hofstede on extreme and acquiescent response styles. Data from approximately 18,000 participants across 19 nations were collected. Using hierarchical linear modeling, authors demonstrated that power distance and masculinity were positively and independently associated with extreme response style. This was because extreme response styles were clearer, more precise, and more decisive, characteristics that are highly appreciated in masculine and high power distance cultures. Individualism, uncertainty avoidance, power distance, and masculinity were negatively associated with acquiescent response behavior. The reasons for this were less clear and obvious. However, the authors suggested that cultures that reject ambiguity and uncertainty would use and prefer a less acquiescent response style, because that style would go against their cultural traits.

While the early 2000s experienced the use of multiple methods on cross-cultural consumer research, there has been an interest in experimental research designs in cross-cultural research as well. In the beginning of the 2000s, some researchers focused on differentiating characteristics across cultures and some others focused on understanding how culture might influence variables related with consumer behavior other than information processing. Aaker and Schmitt (2001) investigated how differences in self-construal (i.e., independent and interdependent self-construal) might affect consumption through the process of self-expression. There were differential levels of recall for similar and distinct items across culturally encouraged selves and there was higher recall for schema-inconsistent information. More specifically, memory for individuals with dominant independent and interdependent selves differed: individuals with a dominant interdependent self had better recall for distinct than similar self-relevant items, while individuals with dominant independent self had better recall for items indicating similarity with others.

In the early 2000s, other researchers also focused on the effects of culture on consumer behavior. More specifically, Kacen and Lee (2002) investigated the influence of culture on impulsive buying behavior. Conducting a multi-country survey with consumers from the United States, Hong Kong, Australia, Singapore, and Malaysia, the authors demonstrated that both regional level factors (i.e., individualism and collectivism) and individual cultural difference factors (i.e., independent and interdependent self-concept) influenced impulsive buying behavior. Similarly, Chen, Ng, and Rao (2005) investigated cultural differences in consumer impatience. Participants from the US may value immediate consumption more than participants from Singapore. Furthermore, Westerners may be more apt to expend their monetary resources to achieve the desirable outcomes, while Easterners could be more prepared to expend their monetary resources to prevent undesirable outcomes. This could be because Eastern culture is more driven to future (vs. present) thinking (Confucian dynamism dimension of Hofstede) and, thus, Easterners tend to be more patient than Westerners.

While most of the research on cross-cultural psychology focused either on individualism or collectivism in the early 2000s, limited research has also focused on bicultural consumers. In an attempt to understand how biculturals (i.e., the ones who are influenced by an East Asian and Western cultural orientation) respond to various types of persuasion appeals, Lau-Gesk (2003) demonstrated that biculturals tended to react more favorably toward both individually and interpersonally focused persuasion appeals. However, Lau-Gesk (2003) showed that this effect was more pronounced among those who integrated the two cultures compared to those who tend to compartmentalize each culture.

During the beginning of the 2000s, cross-cultural research in consumer behavior extended its interest into brands. More specifically, Aaker, Benet-Martinez, and Garolera (2001) investigated the association between brand personality and culture. Aaker (1997) has demonstrated that brands could have salient personality traits (i.e. Sincerity, Excitement, Competence, Sophistication, and Ruggedness) just like people do (i.e. Big-Five personality traits). Extending her work on brand personality, Aaker and colleagues (2001) demonstrated that a set of brand personality dimensions were common in both Japanese and American cultures (i.e., sincerity, excitement, competence, and sophistication), but some of them were culture-specific (e.g., peacefulness for the Japanese and ruggedness for the American). Sincerity, excitement, and sophistication were shared by both Spanish and Americans, while passion was more important for the Spanish and competence and ruggedness were more important for the American consumers. In short, Aaker and colleagues (2001) suggested that the symbolic meaning and value that brands carry were not only affected by the individuals’ perceptions, but also by the cultural characteristics of the country where the consumers lived.

Similarly, Sung and Tinkham (2005) investigated brand personality structures in two different cultures (i.e., Korea and the United States). Passive likeableness and ascendancy were identified more with the Korean participants, which supported their prediction that the Confucian values of tradition and harmony were evident in Korean culture. On the other hand, white collar and androgyny were observed in participants from the United States, demonstrating that professional status and gender roles were more important for the Americans than for the Korean participants.

From 2005, research on culture and consumer behavior has accelerated. Researchers have not only focused on different information processing and response styles across cultures, but have also started to focus on the effects of culture on goals and motivations, on branding, and many other related consumer psychology variables. Briley and Aaker (2006a) first investigated the association between culture and motivation and goals, suggesting that subcultures should also be taken into consideration when considering the effects of culture on consumer behavior. Furthermore, they have argued that both cultural backgrounds and situational forces determine goals. More importantly, Briley and Aaker (2006a) demonstrated that culture influenced decision making as it influenced goal formation. Extending their research, Briley and Aaker (2006b) also demonstrated that culture-based differences in persuasion arose when individuals processed information in a cursory, spontaneous manner. However, the differences dissipated when one’s intuitions were supplemented by more deliberative processing. Furthermore, their results showed that North Americans were more persuaded by promotion-focused information, and Chinese were more persuaded by prevention-focused information. However, this was only valid when initial, automatic reaction to messages was given.

While Aaker and her colleagues studied boundary conditions under which culture might be influential on consumers in the beginning of the 2000s, other researchers responded to the call by Maheswaran and Shavitt (2000) and have started to investigate other cultural dimensions (e.g., vertical, horizontal) apart from individualism and collectivism. Shavitt, Lalwani, Zhang, and Torelli (2006a) tested the importance of horizontal (i.e., valuing equality) and vertical (i.e., valuing hierarchy) dimensions of culture. They highlighted several sources of value for the horizontal and vertical distinction of cultural orientations. Following the commentaries by Aaker (2006), Meyers-Levy (2006), and Oyserman (2006), the authors further conceptualized a new research agenda on culture and how it could be studied from the perspective of horizontal and vertical dimensions (Shavitt, Zhang, Torelli, & Lalwani 2006b).

Starting from 2005, research on culture and branding has gained more attention. More specifically, researchers in cross-cultural psychology investigated how culture influenced brand extension decisions and also how consumers responded to brand failures across different cultures. Monga and John (2007) investigated how consumers from Eastern and Western cultures might differ in terms of their styles of thinking (i.e., analytic versus holistic) and how these different styles of thinking might influence brand extension evaluations. Western (Eastern) consumers primed to engage in holistic (analytic) thinking perceived higher (lower) brand extension fit and evaluated extensions more (less) favorably than would otherwise be the case. Extending their research on culture and evaluations of brand extensions, Monga and John (2008) further tested the effects of analytic versus holistic thinking on negative brand publicity. Analytic thinkers were more susceptible to negative publicity information than holistic thinkers. Furthermore, they were more likely to consider external context-based explanations for the negative publicity, which resulted in little or no revision of beliefs for the parent brand. In contrast, analytic thinkers were less likely to consider contextual factors, which led them to attribute the negative information to the parent brand and hence update their beliefs about the parent brand accordingly.

Ng and Houston (2006) compared the attitudes of American and Singaporean consumers toward well-known brands to test the impact of consumers’ self-view on perception of consumer goods. Westerners, who tend to have a personality-oriented independent self-view, focused on the general qualities of the brand. However, Easterners, who tend to focus more interdependently on contextual factors and their relationship with others, associated a brand with its products. Swaminathan, Page, and Gürhan-Canli (2007) demonstrated that the self-concept connection and brand country-of-origin connection might vary based on self-construal. In a set of experimental studies, their results showed that under independent self-construal, self-concept connection was more important. However, under interdependent self-construal, brand country-of-origin connection was more important. Similarly, Ahluwalia (2008) tested the role of self-construal in enhancing a brand’s stretchability potential. The results of a set of experiments demonstrated that an interdependent self-construal led people to distinguish relationships among the stimuli (e.g., distinguishing the extension from the brand) and hence enhanced the perceived fit of the extension and likelihood of its acceptance. However, these effects hold only for those who were motivated to elaborate extensively on the extension information.

Brands can become mirrors of the cultural traits of individuals in individualistic or collectivistic societies (Holt, 2004). This happens because consumers may link brands to cultural traits (Aaker et al., 2001). Aaker and colleagues (2001) have shown that culture could affect brand personality dimensions. Some brands in the United States (i.e., individualistic culture) were perceived as rugged (e.g. Marlboro), and some in Japan (i.e., collectivistic society) were perceived as peaceful. Research suggested that the brands that embraced more cultural values had higher chances of becoming icons (e.g., Harley Davidson, Nike, Apple, Vodka, etc.) because they created a strong connection with culture (Holt, 2004). Holt (2004) explained that “iconization” was not about the brand performance, but more about the symbolic meaning that is carried with its brand personality traits. Iconic brands, similarly to iconic people, are idealized by consumers and desired to become part of consumers’ lives. Shavitt, Lee, and Johnson (2008) have summarized that culture could affect brand decisions. Their results showed that in individualistic cultures, consumers choose brands based on their attributes, advantages, and available information on the brand. In collectivistic cultures, instead, consumers are influenced by familiarity, friendliness, and perceived honesty of the brand.

Shavitt and colleagues (2006a) further proposed that consumers who belonged to the vertical individualistic culture might be more driven toward status symbols, such as prestige and possession, that transmit higher performance and achievement compared to others. In vertical-individualist societies or cultural countries (e.g., USA, Great Britain, France), individuals cared more about status, achievements, and demonstrating themselves to others. However, in horizontal-individualist societies or cultural countries (e.g., Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Australia), individuals were not prone to differentiation and they liked to view themselves as one group, with equal members (Nelson & Shavitt, 2002).

Apart from the research on brand evaluations, researchers also investigated the cultural influences on product evaluations. Hong and Kang (2006) tested the effect of country of origin (i.e., Germany or Japan) on judgments of quality and desirability of products. The results of their research demonstrated that when the product was typical of those manufactured in the country, identifying the country of origin increased its product evaluations regardless of whether industriousness or brutality was primed. The authors concluded that the animosity toward a product’s country of origin had a negative effect on product evaluations only when the product was not one on which the country’s reputation was based.

In short, research conducted between the early 2000s and 2010 mainly focused on (a) how different cultural orientations (e.g., horizontal vs. vertical) might influence consumer behavior, (b) product and brand evaluations across cultures, and (c) influence of culture on goals and motivations apart from their influence on information processing as well as development of culture-related phenomenon (e.g., cultural icons). Other than the diagnosticity and accessibility explanations, cultural norms, expectations, and motivation were also taken into account to explain the effects of culture on consumer behavior.

Culture and Consumer Behavior Research from the 2010s to Today

With the increasing trend for research investigating the effects of culture on consumer behavior in the early 2000s to 2010, the early 2010s experienced the maturity stage. Apart from a few papers on global and local branding and the effect of cultural orientation on brand extensions, in the early 2010s, researchers mostly focused on food consumption and spending tendencies as a function of cultural orientation.

Torelli and Shavitt (2011) demonstrated the influence of power (personalized vs. socialized) on information processing dependent on cultural orientation (individualism vs. collectivism). Vertical individualists had an increased tendency to stereotype products (i.e., recognize better information that is congruent to prior product expectations) when they were primed with personalized power. However, horizontal collectivists displayed a greater tendency to individuate products (i.e., recognize and recall better information that is incongruent with prior expectations), when they were primed with social power.

The early 2010s experienced the rise of cross-cultural consumer research on understanding global and local brands. Torelli, Özsomer, Carvalho, Keh, and Maehle (2012) focused on the impact of cultural traits on global brand concept. More specifically, the authors used the Schwartz’s Value Survey (1992) to define a globally accepted brand concept. They made a distinction between the cultures based on horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism, and linked this distinction with the branding concept. They suggested that a brand concept related to openness was more preferred by horizontal individualists. However, a brand concept related to self-enhancement was preferred more by vertical individualists.

Strizhakova, Coulter, and Price (2012) not only focused on how consumers’ culture affected global brand preference, but also acknowledged the importance of global brands’ identities in shaping the global identity of individuals. They investigated the mixture of global and local identities (referred to as “glocal” identity) and its effect on consumer behavior. The authors ended up identifying four groups of consumers: globally engaged, glocally engaged, nationally engaged, and unengaged consumer segments. Furthermore, they studied the effect of each one of these groups on involvement with local and global brands, use of local and global brands to signal their selves, and purchase of global and local brands. The results of their studies suggested that the globally engaged (vs. nationally engaged and unengaged) consumers had a stronger engagement and identification with both global and local brands. The globally engaged (vs. nationally) were more likely to purchase global brands. Moreover, the unengaged (vs. nationally engaged) consumer segments displayed lower interest for patriotic and national ideologies.

Research on brand extensions and the effect of culture on brand extensions have continued in the early 2010s. Torelli and Ahluwalia (2012) demonstrated that culture was important also in the congruity perceptions between a brand and a product as it could influence the evaluations over brand extensions. In a series of experiments, their studies showed that consumers had more favorable attitudes toward culturally congruent brand extensions (e.g., Sony electric car rather than Sony coffee machine) when both the parent brand and the product were culturally symbolic. Spiggle, Nguyen, and Caravella (2012) further suggested the brand extension authenticity (i.e., the extent that an extension carries the originality, uniqueness, heritage, and values of its parent brand) as a complementary concept to perceived fit in brand extension evaluations. They showed that authentic extensions enhanced consumers’ attitudes, purchase likelihood, and recommendation intentions of the extended product to others.

Kubat and Swaminathan (2015) have studied the brand preference of bicultural consumers. Results demonstrated that among bicultural consumers, the degree to which a brand symbolizes a certain culture moderated the impact of bilingual advertising (vs. English advertising) on brand preference. More specifically, brands that were low in cultural symbolism enhanced brand preference among bilinguals when advertised bilingually. This happened when bicultural consumers perceived their host culture and their ethnic culture identities as compatible (vs. incompatible). Hence, at high levels of bicultural identity integration, bicultural consumers preferred a bilingual ad more, compared to an ad only in English, but only for a less symbolic brand. Relatedly, Torelli, Chiu, Tam, Au, and Keh (2011) showed that concurrent exposure to symbols of two dissimilar cultures (e.g., American Batman toys with a made-in China label) drew the consumer’s attention to the defining characteristics of the two cultures. Hence, the authors suggested that this resulted in higher perceptibility of cultural differences for the same commercial product.

Research on culture and consumer behavior in the early 2010s has also focused on the way in which consumers considered the relation between the endorser in an ad and the content of it in terms of the fit between them. Kwon, Saluja, and Adaval (2015) empirically showed in a series of four studies that culture might affect the endorser-content fit perceived by the participants. More specifically, they showed that individuals in collectivist cultures expected a fit between the endorser’s message and the endorser. If there was no fit, individuals in collectivist cultures tended to evaluate the ads less favorably. Individuals in individualist cultures did not have such expectations and they treated the message and the endorser as separate information. Hence, they were insensitive to incongruences between them.

Research on cross-cultural consumer behavior also focused on how consumers across cultures responded to unsatisfactory experiences (Ng, Kim, & Rao, 2015). Ng et al. (2015) demonstrated that collectivists were more likely to switch brands if they regretted their group for not taking action to prevent product failure. Individualists were more likely to switch brands if the regret and the inaction to prevent product failure came from the individuals, rather than the group of belonging.

Research in the early 2010s extended cross-cultural consumer research on aspects other than brand and product evaluations. For example, Gomez and Torelli (2015) demonstrated that making a particular culture salient (e.g., French vs. American) caused people to be more sensitive to the presence (vs. absence) of nutrition information in food labels. Moreover, French consumers were less likely to prefer foods that displayed (vs. did not display) nutrition information. Gomez and Torelli (2015) suggested that this was because the information was incompatible with the cultural norm of hedonic food consumption for the French consumers.

Research on cross-cultural consumer research in the early 2010s has also considered the effect of national culture on consumers’ financial decision making. Petersen, Kushwaha, and Kumar (2015) showed that consumers’ financial decisions depended not only on prior experiences or firm’s characteristics, but also on cultural orientations. The authors focused on three of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions: long-term orientation, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity in the country of origin of the respondents, to understand the impact of those on savings rate tendency, credit card purchases, or general spending patterns. Their results demonstrated that individuals from countries with high long-term orientation were more affected by prevention-focused advertising messages to decide on their savings rate. Individuals from cultures with low uncertainty avoidance were more affected by promotion-driven ads and were more likely to use the credit card to make purchases. Finally, individuals from highly masculine cultures were more likely to overspend and react more positively to promotion-focused advertising addressed at extending their spending patterns.

More recently, DeMotta, Chao, and Kramer (2016) tested the effect of dialectical thinking on the integration of the contradictory information. Results demonstrated that low dialectical thinkers expressed more moderate attitudes when they processed contradictory information. Consumers low in dialectical thinking processed the contradictory product information less fluently, which reduced their judgmental confidence. As a result, these consumers had more moderate attitudes toward the contradictory information.

In short, research on cross-cultural consumer behavior has continued to investigate issues related with consumer behavior in the early 2010s. Although there has not been an increasing trend on cross-cultural consumer research in the early 2010s, most of the research focused on perception of global and local brands, brand extensions, and consumer behavior related with food consumption and spending tendencies. Furthermore, there has been some research investigating the other cultural orientations (e.g., masculinity, uncertainty avoidance, or strong national identity) apart from focusing only on individualism and collectivism orientations.

What Lies Ahead in Cross-Cultural Consumer Research

Throughout this chapter, we have proposed a timeline that the cross-cultural consumer research has gone through since its early findings in the late 1990s (see Figure 29.1). We have suggested that there have mainly been three phases that cross-cultural consumer research has gone through to the mid-2010s. Although the interest in cross-cultural consumer research has gained increased momentum in the 2000s, this increased momentum entered a maturity stage where there has been steady progress since. We suggest that researchers might further investigate the role of culture on (1) experiences, (2) coping with psychological threats, (3) consumption emotions, and (4) the use of digital and social media. In the following sections, we provide our call for research into each one of the previously mentioned concepts.

Figure 29.1 Timeline of cross-cultural consumer research

Culture and Experiences

Most of the research on culture has so far focused on branding and product evaluations (e.g., Hong & Kang, 2006; Kwon et al., 2015; Torelli & Ahluwalia, 2012). Culture surely has an important role in how consumers perceive the personality traits of brands (e.g., Aaker et al., 2001), or how responsive consumers are to marketing communications (Pauwels, Erguncu, & Yildirim, 2013).

However, most of the research seems to be driven toward the materialist side of what marketing offers (i.e., the product). We believe there is still a gap in the literature on culture and consumer behavior that might address the impact of culture on preferences for the materialistic versus experiential consumption. When would collectivists prefer experiential consumption to a materialistic one or a materialistic to an experiential one? Similarly, when would individualists prefer experiential consumption to a materialistic one, or a materialistic to an experiential one? Reviewing the literature, Gilovich, Kumar, and Jampol (2015) suggested that people get more satisfaction from experiential (vs. materialistic) purchases because: (1) experiential purchases enhance social relations, (2) experiential purchases develop a bigger part of one’s identity, and (3) they are evaluated more on their own terms than material purchases. We suggest that future research might further investigate the role of cultural orientations on satisfaction from experiential purchases.

Culture and Psychological Threats

Literature on psychological threats suggests that culture might be a source of relief for threatened individuals. The reason for this is that culture enriches individuals with meaning in life (Becker, 1971; Van den Bos, 2009). According to Becker (1971), culture imposes a set of rules, customs, and goals to individuals, which may boost their self-esteem and mitigate the meaning threats the individual is experiencing.

Previous literature has demonstrated that when consumers experience mortality threats, their reaction and preference for brands will be affected by the fear of death (e.g., they would be willing to pay significantly more for prestigious brands in mortality threat condition versus no-threat condition; Mandel & Heine, 1999). Instead, when consumers experience intelligence threats, they reflect the effects of this threat not only on their academic results but also on the brands they use, by choosing brands that signal intelligence. Moreover, under social identity threats (e.g., racial discrimination to Afro-Americans), people try to mitigate the threat by choosing for their children names that convey status (e.g., Harvard or Alexus; Rucker & Galinsky 2008). We suggest that future research might investigate how cultural orientations might influence the way consumers cope with different types of meaning threats.

Culture and Consumption Emotions

Culture is an important factor to influence how one experiences emotions. It provides meanings to many different emotions such as happiness, sadness, anger, and fear. While one might wear black to a funeral in one culture (e.g., Western culture), another person from another culture (e.g., Asian culture) might wear white to a funeral. Hence, we suggest that how culture influences how different emotions are experienced is an important area that deserves future investigation. In this chapter, we mainly focus on happiness as a consumption experience.

Happiness is defined as “a state of well-being and contentment; a pleasurable or satisfying experience” (Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary 2016). Research has identified time and money as some of the strongest predictors of happiness (Mogilner, 2010). Time can be spent either working (hence increasing money), or building social relationships. Research has shown that although working hours in the US have increased, individual happiness levels have remained unchanged. In Europe, instead, working hours have decreased and this has led to an increase in happiness (Easterlin, 1995). Mogilner (2010) demonstrated that focusing on money motivated people to work more, but that did not lead to higher levels of happiness. Reminding individuals of time motivated them to spend more of it with important others rather than working and this made them happier. Hence, priming people with the thought of time emphasized social connections and enhanced happiness.

We believe that culture has a strong impact as a predictor of happiness. Culture shapes the focus of goals and rules individuals stick to (Becker, 1971). For instance, in individualistic cultures, since focus is more on inequality and on being superior to others (Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002), happiness might be achieved by spending time working for individual goals rather than socializing. On the contrary, in collectivistic cultures, emphasis is on being similar to the others in the group. This might lead to the prediction that in collectivistic cultures, happiness is achieved by spending time socializing rather than working. However, we suggest that the effect might attenuate if those people in collectivistic cultures work toward a collectivistic goal.

We might also predict culture to moderate the pursuit of happiness gained from excitement versus calmness. Aaker et al. (2001) demonstrated that culture influenced preference for brand personality dimensions. For instance, in research conducted in Spain on brand personality traits, only Sincerity, Excitement, and Sophistication overlapped out of the five brand personality traits (Aaker et al., 2001). In Japan instead, Ruggedness was substituted with Peacefulness (Aaker et al., 2001). We predict that specific cultural dimensions (e.g., excitement vs. peacefulness) can determine happiness pursued from products. More specifically, in a culture characterized by calmness and peacefulness (vs. excitement) consumers would be happier by consuming brands and products characterized by calmness and peacefulness (vs. excitement).

Culture and Digital and Social Media

In 2016, more than 3.4 billion users were registered online, more than 300 million from the number of online registered users in 2015 and almost 500 million more compared to 2014 (www.internetlivestats.com/internet-users/). Toubia and Stephen (2013) recognized that in order for a company to attract customers, it has to incentivize them to be active online.

Research on knowledge creation and knowledge sharing suggested that cultural values had an important role in determining the extent to which individuals are willing to share (Hofstede, 1984). Bhagat, Kedia, Harveston, and Triandis (2002) suggested that in individualistic cultures, people tend to process information by focusing on each piece of it, rather than the whole. For instance, individualists were more accepting of the written and the codified information, while collectivists tended to disregard the written information and focused more on non-verbal content (Bhagat et al., 2002; Hall, 1979). Moreover, individualists were more prone to asking questions and interacting. While individualists preferred formal ways of communication and knowledge sharing, collectivists preferred more the informal ways (Hwang, Francesco, & Kessler, 2003).

All these previous findings demonstrate that cultural aspects are crucial to information and knowledge sharing. Toubia and Stephen (2013) suggested that for companies that were active online, it was not only important to have many user followers, but also to engage them to interact with the company. Hence, finding ways to motivate users to engage online is fundamental. We predict that in individualistic cultures, consumers would interact more with the company in knowledge and opinion sharing, in liking or sharing company content if the message is mostly written and concise, and if it allows the individual to publicly show their knowledge and opinion. On the contrary, in collectivistic cultures, customers engage more if the content is mostly visual, if it does not require the user to “put their face in,” and if it is designed in an informal and warm way. Hence, we expect a positive engagement of online users if the company takes into consideration the impact of culture on online content sharing.

Concluding Remarks

In this chapter, we have provided an overview of the development of cross-cultural consumer research since the late 1990s. We have reviewed the empirical work investigating the effects of culture on consumers. We have demonstrated that although there has been increased interest in investigating the effects of culture on consumer behavior in the early 2000s, cross-cultural consumer research has been in its maturity stage since 2010. We have provided calls for future research where researchers might investigate further topics in consumer behavior.

References

Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3), 347–356.

Aaker, J. L. (2000). Accessibility or diagnosticity? Disentangling the influence of culture on persuasion processes and attitudes. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(4), 340–357.

Aaker, J. L. (2006). Delineating culture. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 343–347.

Aaker, J. L., Benet-Martinez, V., & Garolera, J. (2001). Consumption symbols as carriers of culture: A study of Japanese and Spanish brand personality constructs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(3), 492.

Aaker, J. L., & Maheswaran, D. (1997). The effect of cultural orientation on persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(3), 315–328.

Aaker, J., & Schmitt, B. (2001). Culture-dependent assimilation and differentiation of the self preferences for consumption symbols in the United States and China. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 561–576.

486Aaker, J. L., & Sengupta, J. (2000). Additivity versus attenuation: The role of culture in the resolution of information incongruity. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 9(2), 67–82.

Aaker, J. L., & Williams, P. (1998). Empathy versus pride: The influence of emotional appeals across cultures. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(3), 241–261.

Ahluwalia, R. (2008). How far can a brand stretch? Understanding the role of self-construal. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(3), 337–350.

Becker, E. (1971). The birth and death of meaning: An interdisciplinary perspective on the problem of man. 2nd Ed. Free Press.

Bhagat, R. S., Kedia, B. L., Harveston, P. D., & Triandis, H. C. (2002). Cultural variations in the cross-border transfer of organizational knowledge: An integrative framework. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 204–221.

Briley, D. A., & Aaker, J. L. (2006a). Bridging the culture chasm: Ensuring that consumers are healthy, wealthy, and wise. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 25(1), 53–66.

Briley, D. A., & Aaker, J. L. (2006b). When does culture matter? Effects of personal knowledge on the correction of culture-based judgments. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(3), 395–408.

Chen, H., Ng, S., & Rao, A. R. (2005). Cultural differences in consumer impatience. Journal of Marketing Research, 42(3), 291–301.

DeMotta, Y., Chao, M. C. H., & Kramer, T. (2016). The effect of dialectical thinking on the integration of contradictory information. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 26(1), 40–52.

Easterlin, R. A. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 27(1), 35–47.

Gergen, K. J., Gulerce, A., Lock, A., & Misra, G. (1996). Psychological science in cultural context. American Psychologist, 51(5), 496.

Gilovich, T., Kumar, A., & Jampol, L. (2015). A wonderful life: Experiential consumption and the pursuit of happiness. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(1), 152–165.

Gomez, P., & Torelli, C. J. (2015). It’s not just numbers: Cultural identities influence how nutrition information influences the valuation of foods. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(3), 404–415.

Gürhan-Canli, Z., & Maheswaran, D. (2000). Cultural variations in country of origin effects. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(3), 309–317.

Hall, E. T. (1979). Au-delà de la culture, collection Points Essais, éditions du Seuil.

Han, S. P., & Shavitt, S. (1994). Persuasion and culture: Advertising appeals in individualistic and collectivistic societies. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 30(4), 326–350.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values (Vol. 5), Sage.

Holt, D. B. (2004). How brands become icons: The principles of cultural branding. Harvard Business Press.

Hong, S. T., & Kang, D. K. (2006). Country-of-origin influences on product evaluations: The impact of animosity and perceptions of industriousness brutality on judgments of typical and atypical products. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(3), 232–239.

Hwang, A., Francesco, A. M., & Kessler, E. (2003). The relationship between individualism-collectivism, face, and feedback and learning processes in Hong Kong, Singapore, and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34(1), 72–91.

Johnson, T. P., Kulesa, P., Cho, Y. I., & Shavitt, S. (2005). The relation between culture and response styles: Evidence from 19 countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36(2), 264–277.

Kacen, J. J., & Lee, J. A. (2002). The influence of culture on consumer impulsive buying behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 12(2), 163–176.

Kubat, U., & Swaminathan, V. (2015). Crossing the cultural divide through bilingual advertising: The moderating role of brand cultural symbolism. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 32(4), 354–362.

Kwon, M., Saluja, G., & Adaval, R. (2015). Who said what: The effects of cultural mindsets on perceptions of endorser-message relatedness. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 3(25), 389–403.

Lau-Gesk, L. G. (2003). Activating culture through persuasion appeals: An examination of the bicultural consumer. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(3), 301–315.

Maheswaran, D., & Shavitt, S. (2000). Issues and new directions in global consumer psychology. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 9(2), 59–66.

Mandel, N., & Heine, S. J. (1999). Terror management and marketing: He who dies with the most toys wins. NA-Advances in Consumer Research, 26, 527–532.

McCrae, R. R., & Terracciano, A. (2005). Personality profiles of cultures: Aggregate personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(3), 407.

487Merriam-Webster. Accessed July 30, 2016. www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/happiness.

Meyers-Levy, J. (2006). Using the horizontal/vertical distinction to advance insights into consumer psychology. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 347–351.

Mogilner, C. (2010). The pursuit of happiness time, money, and social connection. Psychological Science, 21(9), 1348–1354.

Monga, A. B., & John, D. R. (2007). Cultural differences in brand extension evaluation: The influence of analytic versus holistic thinking. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(4), 529–536.

Monga, A. B., & John, D. R. (2008). When does negative brand publicity hurt? The moderating influence of analytic versus holistic thinking. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 18(4), 320–332.

Nelson, M. R., & Shavitt, S. (2002). Horizontal and vertical individualism and achievement values: A multimethod examination of Denmark and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 439–458.

Ng, S., & Houston, M. J. (2006). Exemplars or beliefs? The impact of self-view on the nature and relative influence of brand associations. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(4), 519–529.

Ng, S., Kim, H., & Rao, A. R. (2015). Sins of omission versus commission: Cross-cultural differences in brand-switching due to dissatisfaction induced by individual versus group action and inaction. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(1), 89–100.

Oyserman, D. (2006). High power, low power, and equality: Culture beyond individualism and collectivism. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 352–356.

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128(1), 3.

Pauwels, K., Erguncu, S., & Yildirim, G. (2013). Winning hearts, minds and sales: How marketing communication enters the purchase process in emerging and mature markets. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 30(1), 57–68.

Petersen, J. A., Kushwaha, T., & Kumar, V. (2015). Marketing communication strategies and consumer financial decision making: The role of national culture. Journal of Marketing, 79(1), 44–63.

Rucker, D. D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Desire to acquire: Powerlessness and compensatory consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(2), 257–267.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65.

Shavitt, S., Lee, A., & Johnson, T. P. (2008). Cross-cultural consumer psychology. In C. Haugtvedt, P. Herr, and F. Kardes, (Eds.) Handbook of Consumer Psychology, 1103–1131. New York: Psychology Press.

Shavitt, S., Lalwani, A. K., Zhang, J., & Torelli, C. J. (2006a). The horizontal/vertical distinction in cross-cultural consumer research. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 325–342.

Shavitt, S., Zhang, J., Torelli, C. J., & Lalwani, A. K. (2006b). Reflections on the meaning and structure of the horizontal/vertical distinction. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 357–362.

Spiggle, S., Nguyen, H. T., & Caravella, M. (2012). More than fit: Brand extension authenticity. Journal of Marketing Research, 49(6), 967–983.

Strizhakova, Y., Coulter, R. A., & Price, L. L. (2012). The young adult cohort in emerging markets: Assessing their glocal cultural identity in a global marketplace. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(1), 43–54.

Sung, Y., & Tinkham, S. F. (2005). Brand personality structures in the United States and Korea: Common and culture-specific factors. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(4), 334–350.

Swaminathan, V., Page, K. L., & Gürhan-Canli, Z. (2007). “My” brand or “our” brand: The effects of brand relationship dimensions and self-construal on brand evaluations. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(2), 248–259.

Torelli, C. J., & Ahluwalia, R. (2012). Extending culturally symbolic brands: A blessing or a curse? Journal of Consumer Research, 38(5), 933–947.

Torelli, C. J., Chiu, C. Y., Tam, K. P., Au, A. K., & Keh, H. T. (2011). Exclusionary reactions to foreign cultures: Effects of simultaneous exposure to cultures in globalized space. Journal of Social Issues, 67(4), 716–742.

Torelli, C. J., Özsomer, A., Carvalho, S. W., Keh, H. T., & Maehle, N. (2012). Brand concepts as representations of human values: Do cultural congruity and compatibility between values matter? Journal of Marketing, 76(4), 92–108.

Torelli, C. J., & Shavitt, S. (2011). The impact of power on information processing depends on cultural orientation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(5), 959–967.

Toubia, O., & Stephen, A. T. (2013). Intrinsic vs. image-related utility in social media: Why do people contribute content to Twitter? Marketing Science, 32(3), 368–392.

488Triandis, H. C., & Gelfand, M. J. (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 118.

Van den Bos, K. (2009). Making sense of life: The existential self trying to deal with personal uncertainty. Psychological Inquiry, 20(4), 197–217.

Wang, C. L., Bristol, T., Mowen, J. C., & Chakraborty, G. (2000). Alternative modes of self construal: Dimensions of connectedness-separateness and advertising appeals to the cultural and gender-specific self. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 9, 107–115.

Zhang, J., & Shavitt, S. (2003). Cultural values in advertisements to the Chinese X-generation – promoting modernity and individualism. Journal of Advertising, 32(1), 23–33.

Zhang, Y., & Gelb, B. D. (1996). Matching advertising appeals to culture: The influence of products’ use conditions. Journal of Advertising, 25(3), 29–46.