THE CASE FOR EXPLORING CULTURAL RITUALS AS CONSUMPTION CONTEXTS

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN, CHAMPAIGN, IL, USA

During the summer of 2016, the world’s citizens were awash with opportunities to engage with and participate in many captivating cultural rituals, here defined as aesthetic, performative, and symbolic public events occurring on a grand scale that are broadly accessible to consumers via mass and/or social media. From weeks-long celebrations that marked the 90th birthday of Queen Elizabeth II throughout the Commonwealth, to the opening ceremony of the 2016 Rio Olympics, to regional events such as the Running of the Bulls in Pamplona, these symbol-laden, performative events connect consumers to sociocultural discourses, institutions, and values at the most macro level. Yet as popular as they can be (e.g., over 900 million people viewed or streamed the Opening Ceremony of the London Olympics; Ormsby 2012), ritual studies within consumer research overwhelmingly emphasize those occurring between dyads (e.g., gift giving; Belk and Coon, 1993; Otnes, Lowrey and Kim 1993), within family and/or friendship groups (e.g., Bradford 2009; Epp and Price 2008; Wallendorf and Arnould 1991; Wooten 2000), or within self-contained social units such as brand or consumption subcultures (Belk and Costa 1998; Bradford and Sherry 2015; Kozinets 2002).

These studies affirm that rituals can facilitate important individual and relational goals. For example, gift giving and receipt can signal changes in relationship trajectories (Ruth, Otnes and Brunel 1999), and help consumers express filial piety and support social order in kinship and friendship networks (Joy 2001). Ritualistic behavior within subcultures can help consumers escape from the strictures of daily life (Kozinets 2002; Schouten and McAlexander, 1995), or even foster survival in crisis contexts (Klein, Lowrey, and Otnes 2015). Equally revealing are studies of the downsides of ritual participation for dyads, families, or social groups – such as the social obligations that gifts of time and physical effort impose (Marcoux 2009), the ways ritual boredom or even “ritual death” can occur within the family (Otnes, et al., 2009) and how consumers resist ritual participation (Weinberger 2015). In short, Weinberger and Wallendorf’s (2012) observation that most gift-giving research focuses on micro-level behavior and neglects the activity on a broader sociocultural level rings true about ritual scholarship in general.

Granted, exploring well-practiced rituals on micro- and meso-levels, especially those that link to calendric occurrences such as annual holidays – is typically easier than plumbing this behavior on a more macro level. This is because predicting and gaining access to cultural rituals may be difficult, since they may occur infrequently and unpredictably. For example, funerals for beloved citizens or leaders obviously occur on very short notice, and often in locales that may be difficult to access quickly. Nevertheless, I believe if ritual research is to remain salient to the consumer-behavior discipline, scholars must incorporate cultural rituals into the field of study. Stated more bluntly, with few exceptions (e.g., Weinberger and Wallendorf 2012), our field has effectively ceded the study of cultural rituals (sometimes described as “spectacles”) to anthropology, cinema/media/visual studies, history, and sociology (Beeman 1993; Marshall 2002; Morreale 2000).

Recently, some scholars have begun to examine how understanding consumption rooted at the cultural level – and in particular, ritual-related topics – can inform marketing practice. For example, studies explore how marketers incorporate rituals into customer interactions and commercial offerings (e.g., Bradford and Sherry 2013; Dobscha and Foxman 2012; Otnes, Ilhan, and Kulkarni 2012). This cross-pollination of theoretical approaches toward ritual study and perspectives and problems emanating from retailing and services marketing are important to the field. Indeed, as events are often supported by substantial financial and human capital from commercial sources, cultural rituals afford scholars unique opportunities to continue deepening our understanding of applied consumer behavior.

I structure this chapter as follows: first, I make my case for the importance of broadening the scope of consumer scholarship to include cultural rituals, and for illuminating the impact of ritualized consumption on a sociocultural level. In doing so, I focus on recent cultural rituals staged by one institution – the British monarchy. After explicating how cultural rituals can illuminate our understanding of several key topics, I delve into the relevance of illuminating a key strategic marketing element – the brand. In sum, I seek to coax scholarship on rituals from within well-mined settings (e.g., under the Christmas tree; around the family dinner table), and into more public, spectacle-laden arenas.

Context: Monarchy and the British Royal Family Brand

Many cultural institutions, especially those embedded within the political and religious spheres, rely on rituals to remain viable and visible. Across the world, the institution of monarchy – or the political system that typically features one ruler – has retained its dominant cultural influence, even as the political power of many royal dynasties has dissipated. The creation myths of many monarchies emanate from ancient beliefs that those ascending to power do so through the will of divine providence. Most royal families also boast long lines of relatively continuous descent; for example, the Imperial House of Japan, which claims to be the longest monarchic dynasty, traces its roots to 660 B.C. Thus, monarchs and their families typically reside atop the apex of the social-class hierarchies within their realms.

For centuries, many of the world’s royal families of Europe, Asia, and Africa have relied on lavish and public cultural rituals to reaffirm their power and status at home or abroad, and/or to instill or reignite national pride in their subjects, as typified here:

In an overwhelming show of royal power, the procession of [France’s] Henry II into Rouen in 1551 included 50 Norman knights, horse-drawn chariots [symbolizing] Fame, Religion, Majesty, Virtue, and Good Fortune, 57 armored men representing the kings of France, musicians, military and regional groups, six elephants and a band of slaves and captives, all of whom moved through the Roman Arch of Triumph … [It also] included public shows at other arches, and an elaborate river triumph with mock battles, boats, and mermen with tridents riding fish.

(Cole 1999, 16–17)

Within their home countries, monarchs typically take center stage during cultural rituals that celebrate royal births, royal birthdays, investitures, coronations, lengths of reigns (e.g., Silver, Golden, and Diamond Jubilees), the ends of wars, and of course, royal weddings. Royal-rooted rituals also commemorate more somber occasions, such as acknowledging a nation’s war dead, or commemorating the passing of monarchs. In October 2016, King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand died after a 70-year reign. Cultural commemorations included a 30-day moratorium on entertainment by citizens, a yearlong mourning period during which citizens and even tourists were urged to wear “respectful colors,” and a parade with hundreds of thousands of spectators as the King’s body was transported to lie in state. Furthermore, “the government … set up a telephone hotline to help people cope … Google Thailand set its homepage to black and white … all TV channels … including … [foreign ones like] BBC and CNN, have been replaced with black-and-white royal broadcasts” (Holmes 2016).

Public-relations arms of monarchies often export carefully crafted spectacles to foreign shores, and participate in well-publicized events during their royal tours. Such occasions allow host countries both to valorize visiting monarchs and to shine the spotlight on their own locales, providing free exposure that can spark economic boosts. After the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge visited India in 2016, Travelocity saw a 25 percent increase in website bookings in the country, and a 200 percent boost in searches for hotel rooms in Mumbai, the royal couple’s first stop on the tour (Lippe-McGraw, 2016).

To illuminate the importance of including cultural rituals in the stable of consumer research, I focus on the contributions of three recent events staged by the British Royal Family Brand (or BRFB; Otnes and Maclaran, 2015) from 2011 to 2016. These are: the Royal wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton, the celebration(s) of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012, and the Queen’s 90th birthday celebration(s) in 2016. Balmer and his colleagues first conceptualized monarchy as a corporate brand, one specifically rooted in heritage and relying on pomp and pageantry to bolster equity (e.g., Balmer, Greyser and Urde, 2006). In our recent exploration of the role of the BRFB in consumer culture, we argue that the potency and appeal of the brand stems from its representation of five highly salient categories of brands – namely, global, family, heritage, human, and luxury. The BRFB is essentially devoid of political power; nevertheless, the touristic and heritage pull of the British monarchy, fueled by strong currents of Anglophilia around the world, is undeniable. VisitBritain asserts “the royal family generates … about $767 million every year in tourism revenue, drawing visitors to historic royal sites like the Tower of London, Windsor Castle, and Buckingham Palace” (Khazan, 2013).

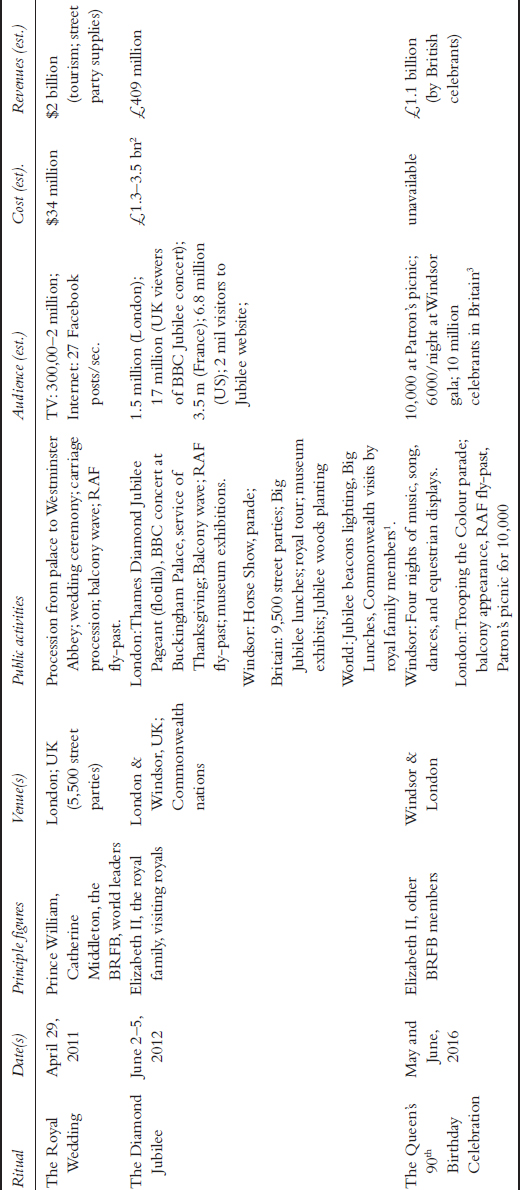

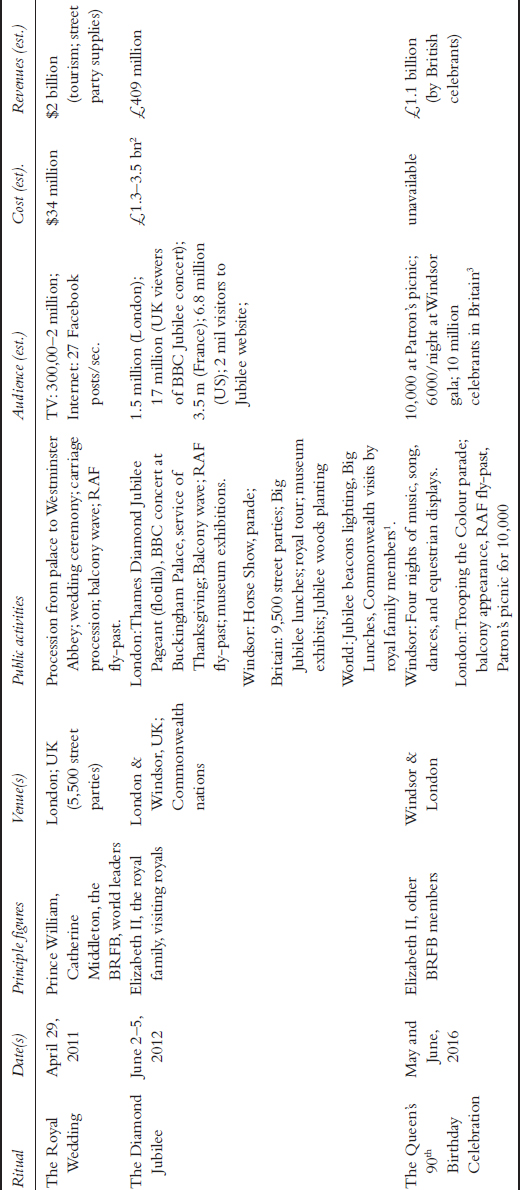

These three BRFB exemplars differ in grandiosity and uniqueness from more “micro,” but nevertheless anticipated and highly orchestrated, rituals associated with the monarchy. These range from daily events such as the Changing of the Guard ceremonies at Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle, to annual pageants like the Queen’s “Trooping the Colour” parade or the Opening of Parliament by the monarch in full regalia. Table 30.1 contains details on these three events. Two other hugely significant occasions to the BRFB during this period, the births of Prince George and Princess Charlotte in 2013 and 2015, also generated tremendous public excitement. But beyond palace officials placing the traditional notices of the births in the forecourt of Buckingham Palace, and quick public viewings of the families when they left the hospital, no widespread spectacles marked these occasions.

Table 30.1 Summary of BRFB cultural rituals: 2011–2016

1 https://www.royal.uk/60-facts-about-diamond-jubilee-celebrations-uk

3 http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/queen-elizabeth-90th-birthday-1.3620788

I leverage these three events, and occasional references to others, to demonstrate how cultural rituals can accomplish the following: (1) showcase the singularity of iconic elements and practices; (2) illuminate the efficacy of supporting sub-rituals; (3) probe linkages between consumption and emotional display; and (4) unpack the salience of spectacular showmanship. I follow the discussion of these benefits by deeply interrogating the reflexive relationship between brands and cultural rituals.

What Cultural Rituals Can Illuminate

Showcasing the Singularity of Iconic Elements and Practices

The three BRFB rituals in Table 30.1 all incorporate exceptional goods, services, and experiences in their design. Some of these clearly meet Belk, Wallendorf, and Sherry’s (1989) definition of “quintessence,” or elements that seem to embody all of the desired, “right” combination of elements within an entity, and in so doing transcend their commercial origins and rise to the status of the sacred and iconic. For example, Catherine Middleton’s wedding gown by the British design firm Alexander McQueen reportedly cost around $400,000. It featured hand-sewn English and French lace, and a nine-foot train designed to imitate an opening flower (Moss 2011). Echoing the Queen’s choice in 1953 to incorporate symbols of the Commonwealth members into the design of her coronation gown, Ms. Middleton’s gown featured hand-appliqued symbols of the four nations within the United Kingdom. Likewise, the Queen’s State Coach created for her Diamond Jubilee includes fragments from iconic British landmarks such as the Royal Yacht Britannia; St. Paul’s, Canterbury, and Durham Cathedrals; Henry VIII’s flagship the Mary Rose; No. 10 Downing Street, and a piece of the apple tree under which Isaac Newton purportedly discovered gravity (Abdulaziz 2014).

Even the world’s wealthiest citizens would have difficulty competing with the BRFB in acquiring items possessing similar cultural caché, because they lack the requisite genetic and historic capital that contribute to the provenance and bolster the mystique of these artifacts. Such unattainability not only imbues these quintessential items with a singular cultural potency, but also enables them to extend the reach and resonance of the cultural rituals in which they are initially embedded. But to prolong these effects, these quintessential artifacts must themselves be emplaced within carefully crafted constructions of post-ritual display, in venues saturated with sacredness and singularity. For example, when Buckingham Palace exhibited Catherine, the Duchess of Cambridge’s wedding gown during the summer of 2012, over 625,000 people bought tickets, contributing to a 50% increase in palace-tour sales over the prior year (Raynor 2012). Likewise, Princess Diana’s bridal gown became the centerpiece of a multi-nation tour that conveyed her life story through photographs and possessions. Reminding visitors that Cinderella fairy tales can indeed come true, the 1981 Royal Wedding and the ensuing displays and discussions that followed reinvigorated consumers’ desires for lavish wedding ceremonies (Otnes and Pleck, 2003) and contributed to Diana’s glamorous image and elevation to the highest echelon of the fame-stratosphere.

Although these artifacts clearly wield cultural and commercial power, the scarcity and singularity of the rituals themselves are likely even more enticing than any particular artifact embedded within them. Rites of passage such as births, marriages, and deaths occur relatively infrequently within any social sphere, and when they do, they typically are marked as the most profound occurrences within the life history of a person or family. The ability to witness such rites as they incorporate pomp and pageantry, and within the context of what has historically been one of the most socially, economically, and politically powerful kinship networks in the world, means these events as a whole may also acquire a quintessence and once-in-a-lifetime aura. Consider too that certain factors of the human condition (e.g., longer life spans, fewer children) mean these occasions are becoming less frequent, while others (e.g., celebrating the 90th birthday of a monarch) spring up to meet the changing times. Thus, understanding what quintessence means with respect to cultural rituals as a whole, rather than with respect to their component parts such as artifacts, is an important research topic to address.

Illuminating the Efficacy of Supporting Sub-Rituals

Many cultural rituals feature myriad sub-rituals that emanate from focal artifacts or events. For example, the Christmas tree is often the center of gift giving, decorating and other family rituals (Otnes et al., 2009). As Table 30.1 demonstrates, the British monarchy devotes exorbitant sums to creating cultural rituals. While often garnering criticism as wasteful and elitist, there is no denying that these “one-off” events appeal to people wishing to witness history first-hand, and who enjoy the ensuing bragging rights associated with having done so. The amount of money spent on travel, hotels, meals, and royal commemoratives (from higher-end pieces sanctioned by the monarchy, to “tourist tat” like thimbles, pencils, bobbleheads, and so on) affirms the appeal of such occasions, and of their tangible representations. For the 2011 Royal Wedding, revenue from “memorabilia alone was estimated at £200m, with the total reaching £480m … when [adding] food and drink” (Gladwell 2011). Likewise, the Diamond Jubilee weekend contributed to an infusion of £120 million into the London economy (Martin 2012).

Yet often, financial assessments of cultural rituals do not accurately capture the impact of sub-rituals throughout the nation and the world that occur in conjunction with these occasions. In fact, some may acquire the status of becoming aspects of the focal iconic celebration. In particular, “street parties” began as part of the nationwide celebration within Britain in 1919 to mark the end of World War I. The website www.streetparty.org.uk describes these events as unique to the U.K., and notes they typically coincide with the occurrence of (happy) royal rituals. This event represents an interesting consumer-culture context because increasingly, participants rely on the marketplace to create specially prepared goods and services as core elements of the festivities. For the thousands of street parties held in the U.K. during the Diamond Jubilee (a period of deep recession in Britain), “Marks & Spencer … sold more than 200,000 jubilee teacakes, 50,000 commemorative cookie tins and … 31 miles of bunting” (“Queen’s Jubilee a Fiesta … ,” 2012). Commentators note that that because these events occur on a local level, they may accomplish more than offering communal expression of respect for the Queen, and in fact may reduce feelings of isolation associated with increasingly urban lifestyles.

Sub-rituals that spring up or become entrenched in larger cultural rituals are largely absent from the consumer-research landscape. As such, exploring the evolution of their meanings for participants, and the ties to the broader cultural ritual they support, represents ripe fodder for exploration. A related but broader topic pertains to understanding how consumers across the globe co-create, participate in, and communicate about cultural rituals when they live thousands of miles away from the focal event. Often, consumers may feel compelled to celebrate these events in real-time, altering their patterns of work or sleep as they navigate tricky time-zone adjustments to do so. Consider the activities of guests at the Ritz-Carlton in Washington, D.C., who gathered to watch the 2011 Royal Wedding:

more than 200 Americans assembled in … the ballroom, where the dress code appeared to be Ascot-inspired. Breakfast [included] scones and clotted cream, English rashers of bacon and a specially commissioned blend of tea with ingredients sourced in Berkshire, the county of the newly-titled Duchess of Cambridge.

(Geoghegan 2011)

In sum, exploring how sub-rituals enable participation in focal but distant occasions – especially in the age of Fear of Missing Out (FOMO; Hedges 2014) – could enrich our understanding of consumers’ and practitioners’ contemporary ritual engagement.

Probing Linkages between Consumption and Emotional Display

Engaging in shared celebration and commemoration means cultural rituals offer unique opportunities for scholars to explore how consumption-laden occasions spur the experience of emotions. In particular, Gopaldas (2014, 995) defines marketplace sentiments as “collectively shared emotional dispositions toward marketplace elements.” Public outpourings of emotion during cultural rituals such as Princess Diana’s funeral represent a unique and rare chance for citizens across the world to experience a shared sense of belonging to humanity – what Victor Turner (1975) terms “communitas” – in the broadest and often the most benign sense. Such sentiments may be increasingly important in a world where divisive and often hostile cultural, economic, social, and political differences dominate contemporary global discourses. At the very least, these occasions provide an opportunity to understand how emotional experiences occur outside of the more typical experimental contexts that dominate consumer research, and in more experiential ones.

The ways in which these visible and sensory-laden emotional displays impact consumers’ experiences of these occasions is also worth exploring. Some personality types (e.g., introverts; Cain 2013), may find outpourings of marketplace sentiments overwhelming or even traumatizing. Others may become anxious or fearful when large and diverse crowds contribute to the inversion of rules that often occurs during ritual enactment – rules that typically govern order and social structure. Thus, the ways the emotional components of cultural rituals impact consumer well-being also should interest researchers whose work aligns with the Transformational Consumer Research paradigm (e.g., Mick et al. 2012).

In addition, how consumers experience marketplace sentiments in cultures unaccepting of, unaccustomed to, or unprepared for mass positive and negative expressions of emotion may prove to be an intriguing research topic. The public outpouring of grief after Princess Diana’s death in Britain took many cultural observers by surprise, with scholars commenting on the incompatibility and incongruity of this experience in a nation whose character is perceived as synonymous with “keeping calm and carrying on” (Thomas 2008).

Unpacking the Salience of Spectacular Showmanship

Cultural rituals often showcase the best practices of spectacle creation, leveraging teams of talented culture-producers charged with dazzling audiences by orchestrating innovative, ludic, sensory-stimulating, and aesthetically-laden experiences. Consider the array of elements comprising the centerpiece of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee celebration, a 1000-strong flotilla down the Thames:

Ten “music herald barges” will unite each section of boats … They’ll include choirs, live bands and orchestras … the Ancient Academy of Music … will perform Handel’s “Water Music” [on] 18th century instruments … the final barge [contains] the entire London Philharmonic Orchestra [playing] pieces associated with [each building] it passes … [at] the headquarters of MI-6 … [its] maestro will cue James Bond’s theme song. Loudspeakers will broadcast … to those standing on the banks … The flotilla includes … a replica of an 18th-century barge, and the Dim Riv, a half-size replica of a Viking longboat … Venetian gondolas, a Hawaiian war canoe, and about 15 specially decorated dragon boats. Tug boats will follow, as will some 70 passenger boats, about 60 motorboats from yacht clubs, and a fleet of amphibious DKUW … boats used in tourists’ duck tours … . More solemn are the ships … that, in 1940 [helped] evacuate 385,000 Allied troops from Dunkirk. When the last boat sails under Tower Bridge … 1,800 energy-efficient LED lights and 2,000 meters of LED linear lights [on the Bridge] will gleam “diamond white” all weekend.

(Adams, 2012)

Given the often competitive aestheticism displayed in the celebration of meso-level consumer rituals (e.g., lavish weddings, bar/bat mitzvahs, quinceañera parties) it is surprising that ritual scholars have not paid more attention to the role of aesthetics within cultural rituals. In fact, few studies explore the benefits (e.g., experiencing positive emotions such as delight; Ball and Barnes, 2017), and consequences (e.g., sensory overload, guilt and regret from overindulgence) of consumer immersion in highly aestheticized cultural spectacles, although some research does explore the consequences of consumers being burdened by ritual preparedness (Wallendorf and Arnould, 1991).

Related to explaining how consumers capture, co-create, and cope with ritual aesthetics, attention should be paid to people’s increasing tendency to use social-media platforms to create their “spatial selves” – or relying on online and offline resources to “document, archive, and display their experience and/or mobility within space and place … to represent or perform aspects of their identity to others” (Schwartz and Halegoua, 2014, 2). The 21st-century version of showing vacation slides to the neighbors manifests itself in people’s ability to immediately disseminate their attendance at coveted cultural spectacles via social media, and bolster their social status, reaffirm their tastes, and flaunt their cultural and economic capital. However, we possess little understanding of how the ways consumer create spontaneous social selves impacts their experiences of the rituals unfolding before them.

Interrogating the Reflexive Relationship between Brands and Rituals

In the introduction to this chapter, I asserted that the relationship between brands and cultural rituals deserves special attention. Support for this claim is rooted in the fact that while rituals clearly act as conduits for culture, brands do so as well (Aaker, Benet-Martinez, and Garolera, 2001). Nevertheless, as is the case with ritual research, much of the research on consumers’ use of brands focuses on the cognitive and affective outcomes of brand use for individuals (e.g., as aspects of their identities or signals of cultural and economic capital; Kirmani 2009; Nelissen and Meijers 2011) and for meso-level groups such as “brand communities” (e.g., McAlexander, Schouten, and Koenig, 2002). But as is evidenced by brand-sponsorship tactics of highly ritualized sporting and media events (e.g., the Olympics, the Super Bowl, awards-show ceremonies) many manufacturers and marketers often seize the opportunities to showcase brands within the context of cultural rituals, and even to try and make brands inextricable elements within these events. In sum, both rituals and brands owe much of their vitality to relying on and reflecting cultural heritage, discourses, iconicity, and myths. Focusing on how brands influence cultural rituals – and vice versa – can help strengthen linkages between the sociological, anthropological, or historical approaches to both phenomena, and can revitalize the relevance of cultural rituals to contemporary marketing strategy and practice.

In this section, I delve more deeply into the reflexive relationship between brands and cultural rituals by exploring the following: (1) ritual brands as ideological symbols; (2) cultural rituals as portals for human brands; (3) the role of brands in commercializing cultural rituals; (4) cultural rituals and place branding; (5) brands and ritual subversion; and (6) rituals as contexts for brand revitalization.

Ritual Brands as Ideological Symbols. Within cultural rituals, branded goods can serve as ritual artifacts, or items Rook describes as communicating “specific symbolic messages … integral to the meaning of the total experience” (1985, 253). Belk, Wallendorf and Sherry (1989) observe some ritual artifacts considered so sacred, only one or a few key players (e.g., shamans) may possess the authority to handle or use them. Marketers are keenly aware that products and brands often play focal roles in rituals. Indeed, a plethora of branded goods is available in the form of memorabilia, special foods and beverages, and products offered by companies that specialize in cultural commemoration.

Consider the Bradford Exchange, a U.S.-based firm that began operations in 1973. Its website homepage touts itself as “the premier source for a vast array of unique limited-edition collectibles and fine gifts that offer an exceptionally high level of artistry, innovation, and enduring value.” Exploring the firm’s website reveals offerings in porcelain, coins, dolls, and other materials that tangibilize events many people might find culturally, pop-culturally, or historically significant. In that vein, it has been quick to issue items that commemorate all of the major rituals and milestones that emanate from the BRFB. Among its offerings to commemorate the 2011 Royal wedding is the “Royal Wedding Jeweled Plate.” Retailing for $49.95, it features a photo of the happy bride and groom exiting their ceremony at Westminster Abbey in the center, while its rim featured repeat motifs of the large blue sapphires and diamonds in the new Duchess of Cambridge’s (formerly, Princess Diana’s) engagement ring. Of course, one of the ultimate goals of commemorative firms such as the Bradford Exchange (and the brand of commemoratives actually produced by the British monarchy itself, the Royal Collection) is that ultimately, people will seek to collect the brand as well as the occasion. Such items may acquire their potency as harbingers of cultural rituals because they represent immediately recognizable and visible evidence that a person endorses and/or has indirectly or directly participated in a ritual. Furthermore, the growth of e-tailing means consumers who seek to engage with these rituals, but who live far from the focal events, can participate through commemorative consumption. Thus, these branded commemoratives that endure long after the streets have been swept of celebratory debris are proof positive that ritual observers have participated in, and perhaps even perceive themselves as a part of, history.

Cultural Rituals as Portals for Human Brands. At their core, cultural rituals often exist to celebrate or commemorate human brands (Thomson 2006). Typically, these are famous people (celebrities, politicians, sports figures) who retain professional image-managers and who themselves strive to become the focus or face of marketing or revenue-generating effort for their organizations or for advertisers. Exploring how heritage-based human brands such as monarchs, renowned spiritual leaders, beloved artists, and literary figures resonate with consumers affords researchers an opportunity to expand the understanding of their potency, as well as their interconnection to cultural rituals.

The British monarchy is the very definition of a human brand: at any given point in history (with the exception of the joint reign of William III and Mary II from 1689–1694), its face has been either one king or one queen since 1066. The outpouring of respect and admiration for the Queen during her 90th birthday celebration also served as a delayed commemoration (at her insistence) of her record as the U.K.’s longest-reigning monarch. As I will demonstrate, this event (among many others involving her and her family during her reign) reveals just how resonant human brands, especially those playing symbolic roles as harbingers of past and present cultural values, can remain within a culture.

Within the BRFB, one of the most famous human brands to emerge in recent years is Princess Diana – and her elevation to cult status still fascinates scholars two decades after her death. Like many successful human (Oprah Winfrey) and non-human brands (e.g., Apple; Volkswagen), Diana’s narrative often focused on her triumph over adversity as an “underdog brand” (Paharia et al., 2011). In the same fashion, Kate Middleton’s coal-mining ancestors and air-hostess mother became crucial threads within her own underdog narrative. Her propulsion from a young woman with a barely-there claim to the aristocracy into the stratosphere of the global social hierarchy wields a massive halo effect for most of the non-human brands she chooses to display (Logan, Hamilton, and Hewer 2013). Furthermore, her underdog narrative enabled commentators to capitalize incessantly on the similarities of her fairy-tale wedding to the Disney version of the Cinderella story – right down to the eerily-similar resemblances of William and Catherine to the animated Prince Charming and Cinderella.

However, one area of potentially fertile research for practitioners is exploring how to balance the two key elements of human brands – namely, the “human” and the “brand.” Obviously, the massive budgets and scale cultural rituals entail require management by professional marketers, event planners, and image consultants, who promote their human brands through tried-and-true techniques. Yet a marketing-savvy and even cynical public may find many of these tactics to be too transparent, leading to a possible tainting of the occasion as more commercial than authentically cultural. For the BRFB, one key task is to balance the accessibility to the monarchy that cultural rituals and their incessant media/social media coverage provide, with maintaining the mystique of the monarchic brand. In other words, the BRFB’s handlers must strive to maintain an appropriate distance for the brand from the “mere celebrities” that populate the pages of tabloid newspapers, magazines such as Hello and People, Facebook and Instagram pages, and Twitter feeds ad nauseam. If the distinction between royals and “mere” celebrities collapses, the legitimacy of maintaining (and funding) the brand may be threatened (even as technically, the BRFB now pays for itself through revenues it generates from the “Crown Estate”). However, other human brands could benefit from explorations of how to create and communicate brand mystique and charisma, and of how the public portrayals of human brands through ritual participation or social media contribute to or detract from desired brand outcomes.

Relatedly, associating established brands with iconic human variants clearly can drive sales – as the “Kate effect” (now expanded to the “Cambridge effect”) clearly demonstrates. This term captures the impact of the Duchess of Cambridge and her children appearing in “High Street” (e.g., off-the-rack) brands that are accessible to many royal fans. After social-media images appear of the family wearing certain brands, sales of these items often skyrocket, and can even cause retailers’ websites to crash, and merchandise stocks to quickly deplete. Although Catherine’s choice of more mainstream brands no doubt exacerbates this effect, in truth the brand choices of the BRFB have spurred such emulative practices for decades. Consider that the corgi was a working dog breed found mainly on farms until Princess Elizabeth received her first one as a pet. However, the actual benefits for consumers of purchasing such mainstream brands that the BRFB endorses through usage remain undertheorized.

Roles of Brands in Commercializing Cultural Rituals. The typically off-the-chart media/social media exposure that cultural rituals enjoy means marketers often aggressively devise ways to insinuate their brands into these activities. These strategies range from serving as official sponsors of rituals and touting this status throughout the events (e.g., in myriad ads during the Olympic games; ensuring athletes wear apparel that prominently features branded logos) to merely appearing on lists of sponsors or suppliers of focal goods and services. The general public may even remain unaware of how extensively rituals such as the Queen’s 90th birthday celebrations relied on commercial support. However, the official website for the event(s) names 29 sponsors, including high-end and stalwart British “heritage” brands such as Jaguar (actually owned by India’s Tata Motors since 2008), Land Rover and the supermarket chain Waitrose.

Nevertheless, ritual organizers may find the concept of blatant brand connections undesirable, or even crass. Tasked with staging the flotilla for the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee (described previously), Phil Smith described the delicate balancing act between creating an event designed to represent history, and enabling his sponsors to take visible parts:

This isn’t an ordinary opportunity for sponsorship. It has to be handled with decorum and taste, as well as sensibility. It won’t be a question of a brand extravaganza on the river by festooning boats with brand names. The … overwhelming majority of brand-owners … appreciate that this is a national event with historic significance and that brands must behave with sensitivity.

(Barnes and Chapman, 2012)

Interestingly, throughout history the British monarchy has demonstrated that it understands how branding practices can contribute to its salience and legacy. In a three-volume study of how different royal houses within Britain promoted themselves to its court and its subjects, the historian Kevin Sharpe (2009, 2010, 2013) traces such practices to the Tudor monarchy in the 1500s. For example, he describes how Elizabeth I relied on branding techniques (such as requiring members of her court to wear cameos with her image) to demonstrate their loyalty, and how she served as the model for the Virgin Mary in illustrations of the earliest printed Bibles. However, contemporary consumer scholars do not plumb the ways brands contribute to consumers’ perceptions of cultural rituals. As noted earlier, many brands themselves rely on consumers’ desires to tangibilize their memories of cultural rituals by acquiring key commemoratives.

Even ordinary brands, or those consumers encounter on a more everyday basis, often take center stage at cultural rituals. The Patron’s Lunch for 10,000 held as part of the Queen’s 90th birthday party (and modeled after the street-party sub-ritual) resembled a British “brandfest” (McAlexander and Schouten 1998) in many ways. It was replete with commemorative hampers provided by the mainstream retailer Marks & Spencer, products and volunteers from brands such as the now-global British pharmacy chain Boots, the iconic alcohol brand Pimm’s, BT, and Unilever. Although the commercial success of these brands stems from their embeddedness into people’s ordinary lives, participants and collectors clearly hungered for these limited-edition brand variants: unused picnic hampers from the event now fetch up to £250 on eBay (Wilgress, 2016).

Cultural Rituals and Place Branding. Since the inception of cultural rituals, both their creators, and spectators expect these events to be chockablock with aesthetics, and many times the ritual venue is a crucial contributor to achieving this outcome. Fortunately for the BRFB, it is inextricably tied to what is considered one of the most historic and picturesque cities in the world – London. Home to iconic sites that teem with royal heritage such as Westminster Abbey (site of all coronations, many royal weddings and monarchic tombs), the Houses of Parliament and those skillfully managed by the national charity Historic Royal Palaces (e.g., Tower of London, Hampton Court Palace, and Diana’s former home Kensington Palace), London offers the perfect backdrop for monarchic cultural rituals. Citizens and tourists alike who experienced the three BRFB rituals discussed here could seamlessly experience an admixture of contemporary, historic, and perhaps even ancient traditions. For example, during the 2012 Diamond Jubilee, they could transition from watching a parade of military might on the Mall in front of Buckingham Palace, to visiting exhibits of Andy Warhol’s portraits of the Queen at the National Portrait Gallery, to taking in theatrical productions about past, present, and even future monarchs in London’s West End.

Many of London’s retail establishments also contribute to and benefit from this fortuitous place branding by creating ties to the BRFB’s rituals in the form of window displays, special menu items, and themed products and services (Figure 30.1). Place branding also extends to locations beyond London; during May and June 2016, the shops in Windsor, England – site of the Queen’s favorite residence and epicenter of her 90th birthday celebration – were festooned with birthday messages and displays of attire such as the broad-brimmed, colorful hats the Queen favors on her ritual walkabouts through the town (Figure 30.2). Yet how such synergies between place and pomp impact consumers’ experiences of cultural rituals – and their subsequent attitudes toward and experiences of the places where they are staged – remains undertheorized.

Figure 30.1 Diamond Jubilee merchandise window display, June 2012

Source: Photo by the author.

Figure 30.2 Queen’s 90th birthday celebration store window, Windsor, England, 2016

Source: Photo by the author.

Brands and Ritual Subversion. Just as brands can serve as harbingers of unity during cultural rituals, they can also provide consumers with vehicles through which to express their displeasure with these occasions. With respect to BRFB-related rituals, countercultural branded goods enable consumers to embrace and express an anti-monarchical ideology when they display, refuse to display, purchase altered goods, or even alter branded goods themselves. As such, subversive ritual brands offer scholars opportunities to explore key discourses related to ideologies and values that rituals and or/brands can express.

At such times, people may create new products that particular subcultures may adopt to undercut what they perceive as an uncritical acceptance of cultural rituals. If successful, some of these one-off products may even result in the creation of a brand. Prior to the 2011 Royal Wedding, the artist Lydia Leith created her “Royal Wedding Sick Bag.” Although initially created “as a joke around the dinner table,” it became hugely popular with those disgusted and fatigued with royal rituals (“Royal Wedding Barf Bags…,” 2011). This variant sold so well that Leith expanded her line to include bags branded for the Diamond Jubilee and the births of Prince George and Princess Charlotte, allowing anti-royalists to thematically express their distaste for the BRFB (and no doubt spurring a new line of collectibles in the process). The success of Leith’s new brand and its extensions points to the need for critical explorations of the sociocultural benefits and consequences of cultural rituals, and the roles of subversive brands within them. Put another way, while marketers may strategically arrange for brands to play active roles in these events, consumers may seek entrepreneurial output that enables them to leverage brands as they engage in activist roles.

Rituals as Contexts for Brand Revitalization. Like many rituals, the three BRFB variants I highlight represent rare historical occurrences that are widely anticipated and motivated by people who wish to have their “ritual longing” satisfied (Arnould, Price, and Curasi, 1999). Such occasions can revitalize well-established brands by providing their manufacturers with opportunities to generate potentially cherished commemoratives, especially if these take the forms of luxury, limited editions that leverage their scarcity (Park, Jaworski, and MacInnis, 1986). As I note earlier, the often-irresistible pull of these cultural spectacles means heritage-brand variants can extend the time span and impact of ritual occasions to include times before and after the core performative activities of the rituals. Research on holidays supports the salience of brands as key ritual artifacts (Rook 1985), and the assumption that they can act as iconic tradition conduits at holiday meals (Wallendorf and Arnould 1991), or during annual gift-giving traditions (Otnes, Lowrey, and Kim 1993).

Yet what remains underexplored is the impact of embedding brands within cultural rituals on metrics such as short- and long-term brand image. One global advertising agency, BBDO, argues that embedding brands into cherished rituals can transform them into “fortress brands,” making it less likely that consumers will forgo them during economic downturns (BBDO: The Ritual Masters, 2007).

In summary, contemporary branding theory recognizes these entities as harbingers of culture, and as repositories of key cultural constructs such as myths and discourses. However, conceptual linkages between brands and rituals remain undertheorized, beyond general observations that marketers can infuse brands with cultural elements such as myths and values to enhance their resonance for consumers (Atkin 2004; Holt 2004; McCracken 1990).

Contemporary Challenges Facing Cultural Rituals

In this final section, I explore how some macro-elements can shape – and disrupt – consumers’ and practitioners’ perspectives about cultural rituals. In recent years, the contemporary global landscape has become increasingly unsettled due to increases in global terrorism, economic uncertainly, political upheaval, and contested debates about human rights and social justice. The staging of public and therefore potentially vulnerable cultural rituals reflects these underlying currents. Security costs to protect the British Royal family and the 50 attending heads of state during the 2011 Royal Wedding was approximated at £20 million. The recent massacre during the Bastille Day celebrations in Nice, France in the summer of 2016 also should encourage exploration of a key question: How can cultural rituals remain viable in a world that faces increasing vulnerability to violence in the public sphere? On the meso level, reactions to such vulnerability have already contributed to the shifting of previously public rituals to more private (and ostensibly secure) spaces. Consider that American Halloween celebrations, traditionally rooted in the nighttime visitation of neighbors’ homes, often now occur in more enclosed, supervised venues such as homes, and even retail stores.

The aesthetic competitiveness and cost of staging globally salient cultural rituals that bring status and regional-pride issues into high relief means debates about their salience increasingly incorporate issues pertaining to social justice and sustainability. Consider that the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games cost China $40 billion in new elements within the civic infrastructure, and renovations and removals of less desirable ones. Observers argue that an event lasting just over two weeks likens the Olympics to a modern-day potlatch (Broudehoux 2007) – one typified by a cycle of grand creation and display, followed by destruction, dismantling, and decay of its requisite components. Adopting a critical stance on cultural rituals – typically the purview of cultural-studies scholars – could also be of interest and value to scholars interested in the domains of sustainable, ethical, and civically responsible consumption.

Likewise, the impact of such viral social-media transmissions on the salience, efficacy and longevity of cultural rituals is an area ripe for exploration by scholars in communication and consumer research. The current grassroots movement of “Pantsuit Nation,” which fostered ritual participation in the form of posting acquisitions and wearing of pantsuits (by men, women, and children) in support of Hillary Clinton’s candidacy for U.S. president, offers an excellent example of a ritual that quickly achieved cultural status, but did not contribute to the desired outcome. In sum, even as the salience of causes or institutions that leverage cultural rituals may be questioned, what seems assured is that cultural rituals themselves will remain salient as viable enterprises involving focal institutions, consumers and commercial entities – and that these rituals retain meanings and importance for these stakeholders.

Conclusion

Incorporating the study of cultural rituals into consumer behavior scholarship is important because these events represent consumer culture writ large. They communicate the values of a culture to domestic and foreign audiences through sensory- and often luxury-laden spectacles, as their organizers seek to remind the world of revered accomplishments and icons entrenched within a specific heritage. Cultural-ritual orchestrators now include corporations that try and leverage the significance and visibility of these events to fulfill key marketing and public-relations goals. These ritual crafters offer up brands, celebrities, technologies, innovators/entrepreneurs, and cultural producers to create memorable, emotion-inducing experiences for participants and observers. Likewise, the often-commemorative consumption choices that members of the ritual audience make signify their valorization of these events, iconicize key components of the ritual, and help them visibly express their allegiance or resistance to the ideologies and themes underlying these occasions.

I hope this chapter offers persuasive evidence that consumer scholars should consider cultural rituals – and the often-localized satellite sub-rituals they support – as important and illuminating research contexts. Besides enabling us to explore the meanings of rituals, they will help us better understand key dimensions of the interplay between these broad cultural (and often global) phenomena, and the roles of the marketplace in creating meaningful experiences for contemporary consumer-citizens.

References

Aaker, J. L., Benet-Martinez, V., & Garolera, J. (2001). Consumption symbols as carriers of culture: A study of Japanese and Spanish brand personality constructs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(3), 492.

Abdulaziz, Z. (2014). History on wheels: 5 things to know about the queen’s new carriage. Retrieved from www.today.com/news/history-wheels-5-things-know-about-queens-new-carriage-2D79756846.

Adams, W. L. (2012). Diamond Jubilee river pageant: A thousand boats set sail in honor of Her Majesty. Retrieved from http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2114386_2114388_2116321,00.html?iid=sr-link1.

Atkin, D. (2004). The Culting of Brands: When Customers Become True Believers. New York, NY: Portfolio.

Arnould, E. J., Price, L. L., & Curasi, C. F. (1999). Ritual longing, ritual latitude: Shaping household descent. The Seventh Interdisciplinary Conference on Research in Consumption: Consumption Ritual.

Ball, J., & Barnes, D. (2017). Delight and the grateful customer: Beyond joy and surprise. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(5), 250–269.

Balmer, J. M. T., Greyser, S. A., & Urde, M. (2006). The Crown as a corporate brand: Insights from monarchies. Journal of Brand Management, 14(1), 137–161.

Barnes, R., & Chapman, M. (2012). Marketing the Queen: Brands face a Diamond Jubilee balancing act. Retrieved from www.campaignlive.co.uk/article/1125369/marketing-queen-brands-face-diamond-jubilee-balancing-act.

504BBDO: The Ritual Masters, Advertising Educational Foundation report, May 11, 2007, Retrieved from www.aef.com/on_campus/classroom/research/data/7000.

Beeman, W. O. (1993). The anthropology of theater and spectacle. Annual Review of Anthropology, 22, 369–393.

Belk, R. W., & Coon, G. S. (1993). Gift giving as agapic love: An alternative to the exchange paradigm based on dating experiences. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(3), 393–417.

Belk, R. W., & Costa, J. A. (1998). The mountain man myth: A contemporary consuming fantasy. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(3), 218–240.

Belk, R. W., Wallendorf, M., & Sherry, J. F., Jr. (1989). The sacred and the profane in consumer behavior: Theodicy on the odyssey. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(1), 1–38.

Bradford, T. W. (2009). Intergenerationally gifted asset dispositions. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(1), 93–111.

Bradford, T. W., & Sherry, J. F. (2013). Orchestrating rituals through retailers: An examination of gift registry. Journal of Retailing, 89(2), 158–175.

Bradford, T. W., & Sherry, J. F. (2015). Domesticating public space through ritual: Tailgating as vestaval. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(1), 130–151.

Broudehoux, A. (2007). Spectacular Beijing: The conspicuous construction of an Olympic metropolis. Journal of Urban Affairs 29(4), 383–399.

Cain, S. (2013). Quiet: The power of introverts in a world that can’t stop talking. New York, NY: Broadway Books.

Cole, M. H. (1999). The Portable Queen: Elizabeth I and the Politics of Ceremony. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Dobscha, S., & Foxman, E. (2012). Mythic agency and retail conquest. Journal of Retailing, 88(2), 291–307.

Epp, A. M., & Price, L. L. (2008). Family identity: A framework of identity interplay in consumption practices. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(1), 50–70.

Geoghegan, Tom (2011). Royal wedding: Breakfast parties in the U.S. Retrieved from www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-13232038.

Gladwell, A. (2011). £200m to be spent' on royal wedding souvenirs. Retrieved from www.bbc.co.uk/newsbeat/article/13157931/200m-to-be-spent-on-royal-wedding-souvenirs.

Gopaldas, A. (2014). Marketplace sentiments. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(4), 995–1014.

Hedges, K. (2014). Do you have FOMO: Fear of Missing Out? Retrieved from www.forbes.com/sites/work-in-progress/2014/03/27/do-you-have-fomo-fear-of-missing-out/#7bab33692391.

Holmes, O. (2016). Thai king’s funeral held at palace as mourners line streets of Bangkok. Retrieved from www.theguardian.com/world/2016/oct/14/thailand-year-of-mourning-death-king-bhumibol.

Holt, D.B. (2004). How Brands Become Icons. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Joy, A. (2001). Gift giving in Hong Kong and the continuum of social ties. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(2), 239–256.

Khazan, O. (2013). Is the British royal family worth the money? Retrieved from www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/07/is-the-british-royal-family-worth-the-money/278052/.

Kirmani, A., (2009). The self and the brand. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19(3), 271–275.

Klein, J. G., Lowrey, T. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2015). Identity-based motivations and anticipated reckoning: Contributions to gift-giving theory from an identity-stripping context. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(3), 431–448.

Kozinets, R. V. (2002). Can consumers escape the market? Emancipatory illuminations from Burning Man. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(1), 20–38.

Lippe-McGraw, J. (2016). After Will and Kate’s royal tour, travel interest in India has spiked. Retrieved from www.travelandleisure.com/travel-tips/travel-trends/will-kate-boost-india-tourism.

Logan, A., Hamilton, K., & Hewer, P. (2013). Re-Fashioning Kate: The making of a celebrity princess brand. NA-Advances in Consumer Research Volume, 41, 378–383.

Marcoux, J. S. (2009). Escaping the gift economy. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(4), 671–685.

Marshall, D. A. (2002). Behavior, belonging, and belief: A theory of ritual practice. Sociological Theory, 20(3), 360–380.

Martin, M. H. E. (2012). The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee weekend brings £120 million cash boost to London. Retrieved from www.standard.co.uk/news/london/the-queens-diamond-jubilee-weekend-brings-120-million-cash-boost-to-london-7819722.html.

McAlexander, J. H., & Schouten, J. W. (1998). Brandfests: Servicescapes for the cultivation of brand equity. Servicescapes: The concept of place in contemporary markets, 377–402.

505McAlexander, J. H., Schouten, J. W., & Koenig, H. F. (2002). Building brand community. Journal of Marketing, 66(1), 38–54.

McCracken, G. D. (1990). Culture and Consumption: New Approaches to the Symbolic Character of Consumer Goods and Activities. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Mick, D. G., Pettigrew, S., Pechmann, C. C., & Ozanne, J. L. (2012). (eds.). Transformative Consumer Research for Personal and Collective Well-Being. London, EN: Routledge.

Morreale, J. (2000). Sitcoms say goodbye: The cultural spectacle of Seinfeld’s last episode. Journal of Popular Film and Television, 28(3), 108–115.

Moss, H. (2011). Sarah Burton: Kate Middleton Wedding Dress Designer. Retrieved from www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/04/29/sarah-burton-kate-middleton-wedding-dress_n_855299.html.

Nelissen, R. M. A., & Meijers, M. H. C. (2011). Social benefits of luxury brands as costly signals of wealth and status. Evolution and Human Behavior, 32(5), 343–355.

Ormsby, A. (2012) London 2012 opening ceremony draws 900 million viewers. Retrieved from http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-oly-ratings-day-idUKBRE8760V820120807.

Otnes, C. C., Crosby, E., Kreuzbauer, R., & Ho, J. (2009). Tinsel, trimmings, and tensions. Explorations in Consumer Culture Theory, ed., John F. Sherry, Jr. and Eileen M. Fischer, London: Routledge, 171–189.

Otnes, C. C., Ilhan, B. E., & Kulkarni, A. (2012). The language of marketplace rituals: Implications for customer experience management. Journal of Retailing, 88(3), 367–383.

Otnes, C., Lowrey, T. M., & Kim, Y. C. (1993). Gift selection for easy and difficult recipients: A social roles interpretation. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(2), 229–244.

Otnes, C. C., & Maclaran, P. (2015). Royal Fever: The British Monarchy in Consumer Culture. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Otnes, C. C., & Pleck, E. H. (2003). Cinderella Dreams: The Allure of the Lavish Wedding. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Paharia, N., Keinan, A., Avery, J., & Schor, J. B. (2011). The underdog effect: The marketing of disadvantage and determination through brand biography. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(5), 775–790.

Park, C. W., Jaworski, B. J., & MacInnis, D. J. (1986). Strategic brand concept-image management. The Journal of Marketing, 50(4), 135–145.

Queen's Jubilee a Fiesta for Souvenir-Sellers. (2012). (AP) Retrieved from www.cbsnews.com/news/queen-elizabeth-iis-diamond-jubilee-a-fiesta-for-souvenir-sellers/.

Raynor, G. (2012). Duchess of Cambridge’s wedding dress helps raise £10 million as Buckingham Palace visitor numbers soar. Retrieved from www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/theroyalfamily/9409550/Duchess-of-Cambridges-wedding-dress-helps-raise-10-million-as-Buckingham-Palace-visitor-numbers-soar.html.

Rook, D. W. (1985). The ritual dimension of consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 251–264.

Royal wedding barf bags made by graphic designer Lydia Leith. (2011). Retrieved from www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/02/16/royal-wedding-barf-bags-m_n_824304.html.

Ruth, J. A., Otnes, C. C., & Brunel, F. F. (1999). Gift receipt and the reformulation of interpersonal relationships. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(4), 385–402.

Schouten, J. W., & McAlexander, J. H. (1995). Subcultures of consumption: An ethnography of the new bikers. Journal of Consumer Research, 22(1), 43–61.5

Schwartz, R., & Halegoua, G. R. (2014). The spatial self: Location-based identity performance on social media. New Media & Society, 1643–1660.

Sharpe, K. (2009). Selling the Tudor Monarchy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sharpe, K. (2010). Image Wars: Promoting Kings and Commonwealths in England 1603–1660. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sharpe, K. (2013). Rebranding Rule: The Restoration and Revolution Monarchy 1660–1714. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Thomas, J. (2008). From people power to mass hysteria Media and popular reactions to the death of Princess Diana. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 11(3), 362–376.

Thomson, M. (2006). Human brands: Investigating antecedents to consumers’ strong attachments to celebrities. Journal of Marketing, 70(3), 104–119.

Turner, V. (1975). Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society. Cornell University Press, 1975.

Wallendorf, M., & Arnould, E. J. (1991). “We gather together”: Consumption rituals of Thanksgiving Day. Journal of Consumer Research, 18(1), 13–31.

506Weinberger, M. F. (2015). Dominant consumption rituals and intragroup boundary work: How non-celebrants manage conflicting relational and identity goals. Journal of Consumer Research, ucv020.

Weinberger, M. F., & Wallendorf, M. (2012). Intracommunity gifting at the intersection of contemporary moral and market economies. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(1), 74–92.

Wilgress, L. (2016). Picnic hampers from Queen’s birthday street party go up for sale on eBay for more than £250. Retrieved from www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/06/14/picnic-hampers-from-queens-birthday-street-party-go-up-for-sale/.

Wooten, D. B. (2000). Qualitative steps toward an expanded model of anxiety in gift-giving. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(1), 84–95.