As we saw in Chapter 1, when we are depressed our brains, bodies and minds shift to different patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving. We can call this a depressed brain or mind state. A key question, then, is how and why this happens. After all, these depressed states are very unpleasant and don’t seem very helpful in our lives. Understanding why our brains can go into depressed patterns is a key research question. In the next few chapters we are going to explore this.

If you’re feeling depressed, you may find these chapters tough going at times because they contain technical information, and it can be difficult to concentrate when you are depressed. Please don’t worry about that. You don’t need to read these sections if you don’t want to, and even if you do read them it is quite likely that you may only remember one or two key ideas, so there is a summary at the end of each chapter. If you wish, just note those key points and go straight on to Part II, ‘Learning How to Cope’. When you feel better, you could return to these chapters, or dip into them. I have expanded them from the first and second editions because depressed people and their relatives often ask to know more about what causes depression. I have also expanded them to explain a new focus on compassion. Being gentle with ourselves will be helpful in our journey out of depression.

It is very easy for us humans to see ourselves as special and different from other animals because we have a certain self-awareness and recently evolved abilities to think, reflect, plan and ruminate – with a kind of ‘new mind’. But even though this is true we also have many motives, emotions and social needs in common because of how our brains have evolved and are constructed. For example, animals (e.g., chimpanzees) can become anxious, angry, lustful, vengeful, sad, distressed, agitated or excited, happy, playful, and affectionate. Like us, too, they seek out certain positive things such as food and comforts, and create certain types of relationships. They can fight with each other over status or territory; they can seek each other out for protection, support and friendships; they can form close bonds; they can develop sexual relationships, and can be very attached to their offspring, protecting them, nurturing them and providing for them. Like us, too, they appear to become stressed and depressed if they are socially rejected, defeated or threatened. Indeed, we see these desires, encounters and relationships going on in their billions in many life forms on this planet every day.

We too are constantly engaging in these behaviors. From the day we are born we seek a loving and caring attachment with our parents. We can struggle for status, recognition and acceptance from other human beings. We want to form relationships with others who care about us and help us. We feel good when relationships go our way. We don’t want to be criticized or rejected: then we can get sad, upset or angry. When things go wrong and we feel unable to achieve these desired goals, and/or we feel unloved, or rejected and inferior, our mood can go down, as it can for any other animal.

We can call all these forms of behavior, with their various desires and efforts, archetypes because they are forms of feeling and thinking that ripple through many life forms, including us. They give rise to our feelings and desires. Look at this carefully:

We did not create these desires for certain types of relationship and feelings – rather, they are created within us, from our genes and our evolutionary history and are shaped by our life experience.

The point is that we all just find ourselves with this body, with this mind with its varieties of emotions, born into particular families in particular places at particular times – none of which we choose. We sort of ‘wake up’ through our childhood to the fact of us ‘being here’ and then try to make the best we can of this strange mind of ours. So, much of what goes on in our minds is not our fault – evolution put these abilities there but, by understanding how our minds work, we can learn how better to cope with unpleasant feelings that can ripple through us, and train our minds to cope. We can influence how our brains are working and steer them towards feelings of well-being and away from depression.

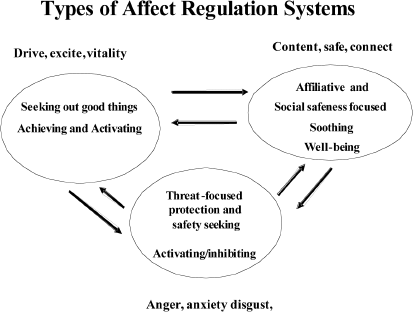

Let’s now look a little closer at how the brain helps us navigate through life, noticing and trying to avoid threats, seeking out things we want, and influencing our feelings in our relationships. The way the brain does this is very complex but we can simplify it in a very useful way. We have special brain systems (networks) that regulate three different types of emotion and action:

These systems are constantly interacting and it is from their interactions that we get ‘states of mind’. Figure 2.1 is a diagram of these interacting systems.

Figure 2.1 The interaction between our three major emotion regulation systems.

As we become depressed the balance between these systems changes and we have far more threat-linked feelings of anxiety, irritability, pessimism, shame and anger, far fewer feelings of motivation, energy and optimism, and also far fewer feelings of contentment, peacefulness and sense of connectedness to other people. It is helpful to understand this in terms of a shift in the balance of feeling and thinking systems. Then we can stand back from the depression and recognize that it is a particular pattern in our brains that we are having to deal with. The reasons these brain systems have become out of balance, or have taken up a new pattern, will be the subject of later chapters.

Thinking about depression in this way gives us an opportunity to think about how we can rebalance the three emotion systems. If you like, we can think about working on ourselves as a kind of physiotherapy for our minds. In the second half of this book we will explore how we can rebalance our systems by working on our behaviors, thoughts and feelings. Exercise, diet and medication may also help, but they are not the main focus of this book (see the appendices for some thoughts on these). Next we explore these three emotion regulation systems in more detail.

Life on our planet faces a variety of dangers, from other life forms that want to eat them, fights with others of their own kind, lack of food or shelter, to viruses, bacteria and so on. Because life forms face so many threats, they need to have systems in their brains that can detect them and respond.2

We can call this the threat-protection and safety-seeking system, or threat-protection system for short. It is designed to detect threats, activate protective emotions such as anxiety and start behaviors that will help us to keep safe, such as running away or avoiding things. In humans and other animals this system can be activated very quickly, giving rise to feelings of anxiety, anger or disgust, with their associated behaviors for fighting, running away, and trying to get rid of things. Note too that we can have these feelings if we see others – especially those we love – in danger or distress: we want to rush in to protect them.

Although this system was developed for our protection, many of the emotions, feelings and thoughts associated with it can cause us problems and indeed underpin many mental health difficulties. For example, our anxiety or anger can become too easily triggered or too intense, or difficult to turn off. We might become anxious about situations we don’t want to be anxious about – such as standing in a queue, going to a party or job interview. Our emotional brain and our logical (new) brain seem to be saying rather different things. When we experience our emotions getting in the way of what we can logically want to do or feel, we tend to see such feelings as ‘bad’ and ‘to be got rid of’, but in fact they are only designed as self-protection. It is often because we don’t understand that they are part of our alarm and self-protection system that we can have such a negative approach to these emotions. When this happens we tend to fight with them, avoid them or even come to hate them rather than work with them.

Our new brains may focus thinking and rumination on threat and losses. The last time I had to take an important exam I found it difficult not to think about it, or to sleep well the night before. That can be useful, of course, because I prepared well (I hope). After the exam I started going back in my mind over what I had written and wondering if I had answered questions correctly or sufficiently, oscillating between confidence and doubt. That is how our minds are, worrying about the future and reflecting on the past. Sometimes focusing on threat and preparing for it is very helpful. However, feeling one’s mind constantly pulled to focus on a threat or loss can be very unhelpful. Then we worry and fret about things, and at times we give up trying altogether, anticipating that it will go badly – so we feel there is no point.

Many researchers are now looking at depression from an evolutionary point of view.3 Research has shown that when we are depressed, an area of the brain (called the amygdala) that is associated with detecting and responding to threats seems to become more sensitive.4 Indeed, some depressed people can have greatly increased anxiety and/or anger and irritability because the threat system has become ‘inflamed’, if you like. This may be linked to threat in our current situation, genetic sensitivity, unresolved anger or anxiety issues from the past, or other reasons, but it is useful to think about some aspects of a depression being linked to this physiological sensitivity in our threat-protection system. We can then consider how to work on reducing this sensitivity and help to settle it down.

The situations that can trigger depressive changes in our brains are linked to particular difficulties, and we will be looking at these in the next two chapters. Situations that are important to us but where we feel we have lost control, or we feel no matter how much we try we can’t reach our goals, or we feel overwhelmed by demands on us, or we find ourselves trapped in situations we don’t want to be in (e.g., isolated, or with critical or unkind others), or feeling defeated or exhausted – can all contribute to depression. Feeling isolated, alone, misunderstood, or unlovable and cut off from others is also strongly linked to depression. Depression is a kind of shutdown, a ‘go to the back of the cave and stay there until things improve’ response.

Depression is not just about having more anxiety and irritability. A key element of depression is that positive emotion systems seemed to be toned down too. We are not able to enjoy things or look forward to things. Things we used to enjoy, such as talking to people, going to parties, planning a holiday or even having sex can become things that are actually unpleasant to do; they fill us with dread and we can see nothing but problems and difficulties in doing them. In fact, although feeling accepted and connected to others is associated with feelings of well-being, when we are depressed we often feel disconnected from other people, as if there is a barrier between us and others, almost as if we are an outsider or an alien. This tells us that positive emotion systems in our brain are toned down. So to help us out of depression we have to practise stimulating our positive emotion systems, to get them active in our brains again.

Recent research has shown that there are in fact two very different types of positive feeling and emotion systems (see page 17).1 One type is linked to a system that is activating and energizing; it is the system that gives rise to desires, and the buzz of excitement if something good happens to us or to people we care about, or even if our football team wins. It energizes us. This emotion system helps us to become active, to seek out good things, and to try to achieve and acquire things in life – it gives us certain feelings and drive.

The other positive emotion system is almost the opposite; it’s not about achieving but about being safe and at peace. It is soothing and calming and gives feelings of contentment and well-being. It is the system that people who meditate try to stimulate.

These two systems evolved over millions of years. Let’s look at them a little more closely.

This system motivates us to achieve things and do things. It gives rise to our wants, and our desires to satisfy these. When good things happen, we can also get a buzz from this system. For example, if you win the lottery tonight and become a millionaire you may have bursts of excitement and become agitated; your mind will be churning with thoughts of your future; you’ll find it difficult to stop smiling and you may also find it difficult to sleep because your mind will be racing. This is the system that can become overactive in people who have bipolar dis order. But if you are very depressed, even winning the lottery might wash over you because your positive emotion system only gives a slight splutter and you quickly get pulled back into the threat system, dwelling on all the problems having money will bring – how much to give to Uncle Tom and Aunty Betty and what happens if you upset cousin Alfred – what’s the point of money anyway if it makes you feel this bad?

Of course, usually the drive system is not nearly as highly activated as this but it gives us our little bursts of energy and excitement. If we are overstressed or push ourselves too hard, this system can get exhausted, and we can start to lose feelings of motivation and interest in things. We start to feel that we can’t be bothered; even deciding what to have for lunch is boring and we can’t think of anything we fancy. We find, as the Rolling Stones once wrote, that we ‘can’t get no satisfaction’.

There are many ways in which the drive system can become exhausted. If we overwork and become very tired the system can start to struggle; it runs out of fuel because we’ve been over using it. If we are under a lot of stress for a long time, this again can affect our positive emotion system and we lose energy and motivation. Feeling helpless and out of control can cause the system to become exhausted. If we are being bullied or criticized at home or work, or if we are in a conflict relationship, or if we are very divided on what to do, whether to stay in this job or relationship or leave – these stressors can gradually tone down the drive system.

So when we are depressed it is useful to think about whether this system has become exhausted and, if so, how we can start to heal it, exploring what it needs to get up and running again. If you are self-critical for being depressed or tired, then this is only going to exhaust the drive system even more. Self-criticism does not – under any circumstances – increase enthusiasm, motivation or pleasure. It motivates through threatening and a fear of failure – that is, through your threat system. Sometimes we have to work hard to become more active and put positive things in our lives as best we can. This can mean deliberately training our attention to focus on positive things – things we appreciate, no matter how small – such as the taste of your first cup of tea in the morning, or the smile of a friend. If we recognize that we have a particular problem in a particular system in our brain then we can design a program to get it going again. Taking exercise can help stimulate this system too.

Useful and important as the drive system is, there are signs that Western society is rather overstimulating it and leading us to believe that we can only be happy if we have and achieve things. This leads people to constantly compare themselves with others, to reflect negatively on themselves – and that’s pretty depressing, because it takes away enthusiasm and hope of success. We are also overworking and getting exhausted in the drive for the ‘competitive edge’ or proving ourselves competent.

How does kindness fit into feelings of depression and a lack of well-being? Well, it does so in some very interesting ways. First, we should note that in our brains we have a system that regulates the experience of ‘having sufficient, enough, and contentment’. When animals are not dealing with threats, and are not having to pursue things like food or other resources, they can be quiet, resting, quiescent and peaceful. We now know that this state is not just about low activity in the threat system. There is a system in our brain that gives us feelings of contentment where we are not seeking or feeling driven to achieve things – we are happy as we are, right now, in this moment. Think back to times you might have had feelings of contentment, being satisfied with where you were. People who meditate and become mindful (see Chapter 7) and spend time trying to develop calm states of mind often describe positive feelings of contentment, well-being and peacefulness.

But what has this got to do with kindness? To understand this you need to know that the evolution of our brains and bodies always uses systems that already exist. It is very difficult for evolution to design something totally new. The system that gives us our feelings of peacefulness, calmness and soothing is also linked to affection and being cared for. How did that happen? Simply put, millions of years ago the young of our mammal ancestors that were fed and protected survived and so passed on the genes for care and protection. Over millions of years these spread throughout the world. Today, whether you look at birds looking after their chicks in the nest, your family dog looking after her pups, monkeys caring for their infants or humans loving their babies, we see the enormous importance of love and affection in the process of protecting and caring. If you look carefully at these interactions you will also see something very interesting. When in close contact with its mother, the young infant is often peaceful and quiet.5 An extreme example is the emperor penguin, where the baby chick has to sit on the parent’s feet and not move or it will freeze.

What do caring relationships do to and for the child? First, they turn off the child’s threat system. Indeed, think how a mother is often able to calm and soothe a distressed infant. Through the mother’s tone of voice, or cuddling and gentle soothing, the child’s brain registers that it is being looked after and this calms the threat system. This ability to soothe distress with kindness is fundamental to how our brains work. It is part of our evolutionary design. Our brains are designed to want kindness, and can respond to kindness. And it’s not only in child–parent relationships that kindness is powerful. Kindness is one of the most important qualities that people look for in a long-term partner; it’s one of the most important qualities people look for in friendship and (along with technical ability of course) one of the most important qualities we look for in our doctors, nurses, teachers and psychotherapists. We may not always be good at giving it, and sometimes we can be grumpy toads – but humans value and look for kindness because their brains are organized to feel more secure and safe in the context of kindness.

To help you think about how kindness operates in the body, consider the following scenario. You are upset about something: maybe a project you were planning hasn’t worked out, or you are very disappointed over something, or someone you spoke to was unkind. Imagine you go to a friend, but they are very dismissive or they quickly switch the conversation around to their own difficulties, or are even critical of you and tell you to stop making mountains out of molehills. How will you feel. How will you feel in your body? Think about that. Now imagine you go to a friend who listens very carefully to your story. They sympathize and empathize with your upset, they say how they can understand why you are upset. Maybe they put an arm on your shoulder. How do you feel? You see, you already know in your heart that kindness will have a very different impact on your body. You have inner wisdom on the value of kindness and can learn to tune into it rather than getting caught up in the angers, frustrations, disappointment and fears of your threat system. As we will see in a moment, this is also the case for our own self-focused thoughts and attitudes to ourselves – these too can be rather bullying, but we can train them to be kind and supportive.

Kindness is important, too, because it underpins trust. When we trust people we are no longer orientated by threat, nor are we striving to impress them. We can turn to them if we need to. In a way kindness and trust can also tone down aspects of our drive and threat-protection systems and bring them more into balance. This is important to understand, because sometimes people who are vulnerable to depression feel they have to drive themselves hard, to impress others or to be liked and accepted. The drive system gets out of balance because of feeling insecure with other people, which means that the soothing system requires some development. We will be looking at exercises to help you with this later.

Without going into too much detail, these kinds of emotions use different chemicals in our brains, in different patterns to those of excitement and achievements.1 These calm, good feelings of well-being are linked to endorphins (the body’s natural opiates) and a hormone called oxytocin. This hormone has generated a lot of interest recently because it is linked to feelings of closeness and trust with other people, and the warm feelings we get from affiliation and affection.5

Our thoughts can also affect how these systems work and balance each other. Over the past two million years or so the human brain has been evolving abilities to think, to imagine, to predict, to ruminate and plan. We can form mental images in our minds. We can imagine the future, and think about how we can create a future that we want (or feel trapped in one we don’t want). Much of our life is spent thinking about and planning for our wants; generating hopes, planning for our future, developing goals and worrying about obstacles and setbacks. Animals simply live out their lives, but humans are life planners and try to live according to their plans. This thinking gets pretty sophisticated. Indeed, it is because we can think like this that we have an intelligence that underpins science and technology. Our ability to imagine, think and plan with some complexity is central to the human mind.

As we will see later though, what we focus and think about, and how we focus our attention and thinking, can seriously affect our moods. Monkeys don’t worry about being able to pay the mortgage, or failing a job interview, nor how to get out of a marriage; nor do they ruminate about feeling depressed in the future. Humans clearly do, though, and this can be one reason for low mood.

We also have a complex language, can talk to each other and can share wonderful ideas and feelings. We can share and build our plans and goals together. We can use symbols that help us to think. We have also evolved a sense of self-awareness. We have an awareness of being ‘alive’, being a self with a consciousness. These are wonderful abilities and give rise to our science, art and culture. We create and follow fashion because we have a sense of ourselves and how we wish to appear to others. We can create a sense of self-identity and this varies according to where we live. Think how different our self-identity would be if we grew up in a Buddhist monastery, in the backwoods of Alaska, in glitzy Hollywood or in a poor inner-city area.

However, there is a downside to these wonderful new mind abilities, because if our thinking about ourselves or future becomes overly threat- or loss-focused then we can lock ourselves into threat-process thinking and some very unpleasant feelings indeed.

To help you explore how thoughts, images and memories can have powerful effects on systems in our brains, look at the brain depicted in Figure 2.2. It demonstrates how external things and our imagination of external things can work in a very similar way. Let’s start by using examples that I commonly use and have discussed on my CD Overcoming Depression: Talks With Your Therapist.

Figure 2.2 The way our thoughts and images affect our brains and bodies.

Imagine that you are very hungry and you see a lovely meal set out on a table. What happens in your body? The sight of the meal stimulates an area of your brain that sends messages to your body so that your mouth starts to water and your stomach acids get going. Spend a moment really thinking about that. Now suppose that you’re very hungry but there isn’t any food in the house, so you close your eyes and imagine a wonderful meal. What happens in your body then? Again, spend a moment really thinking about that. Well, those images that you deliberately create in your mind can also send messages to parts of your brain that send messages to your body, so again your mouth will water and your stomach acids will get going. Remember though, this time there is no meal: it’s only an image that you’ve created in your mind, yet that image is capable of stimulating those physiological systems in your body that make your saliva flow. Take a moment to think about that.

Here’s another example, something that some of us have come across: you see something sexy on TV. This may stimulate an area of your brain that affects your body, leading to arousal. But equally, of course, we know that even if you’re alone in the house you can imagine something sexy and that can affect your body. The reason for this is that the image alone can stimulate physiological systems in your brain in an area called the pituitary, which will release hormones into your body.

The point is that thoughts and images are very powerful ways of stimulating reactions in our brain and our body. Take a moment and really think about that, because this insight will link to other ideas to come. Images that you deliberately create in your mind and your thinking will stimulate your physiology and body systems.

Let’s consider a more depression-linked example. Suppose someone is bullying you. They are always pointing out your mistakes or dwelling on things you are unhappy with, or telling you that you are no good and there is no point in you trying anything, or being angry with you. This will affect your threat-protection and stress systems. How do you feel if people criticize you? How does it feel in your body? Spend a moment thinking about this. Their unpleasantness will make you feel anxious, upset and unhappy because the threat emotion systems in your brain have been triggered. If the criticism is harsh and constant, it may make you feel depressed. You probably would not be surprised by that. However, as we have suggested, and here is the point – our own thoughts and images can do the same. If you are constantly putting yourself down this can also activate your stress systems and trigger the emotional systems in your brain that lead to feeling anxious, angry and down. That’s right – our own thoughts can affect parts of our brain that give rise to more stressful and unpleasant feelings. They can certainly tone down positive feelings. Who ever had a feeling of joy, happiness, contentment or well-being from being criticized? If we develop a self-critical style then we are constantly stimulating our threat system and will understandably feel constantly under threat. Self-criticism then stimulates the threat system. This is no different from saying that sexual thoughts and feelings will stimulate your sexual system, and the thoughts of a lovely meal will stimulate your digestive system.

There are many reasons for becoming self-critical. One common reason is that others have been critical of us in the past and we simply accept their views as accurate. We don’t stop to think whether they were genuinely interested in our welfare and really cared and wanted to help us – in fact they may just have been rather stressed and irritable people who were critical of everyone. We have gone along with their criticisms of us – as one often does as a child – and never stopped to think if they are accurate or reasonable. Or it may be that we are trying very hard to reach a certain standard, or to achieve something, or present ourselves in a certain way. When it doesn’t work out as we would like, this can frighten us because we may think we have let ourselves down or other people will reject us. In our frustration we then criticize ourselves and take our frustration out on ourselves. All very understandable, but not helpful, because we are giving ourselves negative signals that affect our brains. Research on what happens in people’s brains when they are self-critical confirms that it really is the case that we stimulate threat systems in our brain. The more self-critical we are, the more those systems are stimulated. Learning to spot self-criticism and what to do about it is a key issue in later chapters.

We have spent some time looking at the three emotion regulation systems and we explored a system in the brain that helps to soothe and calm us when things are hard or we are frightened. We feel soothed when other people are kind and understanding, supportive and encouraging. We have a system in our brains that can respond to those behaviors from others. Suppose that when you are struggling there is someone who cares about you, understands how hard it is, and encourages you with warmth and genuine care – how does that feel? Maybe you could spend some time thinking about this right now. Or imagine that you are learning a new skill and finding it hard; maybe other people seem to be getting the hang of it more easily than you. However, you have a teacher who is very gentle and warm, pays careful attention to where your difficulties are, helps you see what you are doing right and how you can build on those good things. Compare this with a teacher who is clearly irritated by you, makes you feel you’re holding up the class, and focuses on your deficits. Most of us are going to prefer the first type of teacher, and indeed will do much better.

So using exactly the same idea as imagining how a meal can stimulate sensations and feelings in our bodies linked to eating, we can think about how our own thoughts and images might be able to stimulate the kindness and soothing system. If we can learn to be kind and supportive – to send ourselves helpful messages when things are hard for us – we are more likely to stimulate those parts of our brain that respond to kindness. This will help us cope with stress and setbacks. As this book unfolds, you will learn how to engage with compassionate attending, thinking, behavior, imagery and feeling (see Chapter 9). Bear in mind all the time that this is about helping you to re-balance systems in your brain.

What happens in our brains when we focus on self-critical or self-reassuring and self-compassionate feelings? Self-criticism stimulates parts of our brain linked to threat, whereas self-compassion and reassurance stimulates parts of our brain linked to empathy and soothing. However, there is an added complication. For some people who are very self-critical, starting to become self-compassionate can seem like a threat. Some people feel that wanting kindness, or even making an effort to be kind and gentle to oneself, is a weakness or an indulgence. They believe that either they or others simply don’t deserve it. Our research indicates that when people first start to be kind to themselves, they can feel it as rather strange or threatening. They have to work through these ‘fears’ to start training their minds in self-kindness.

Nonetheless, there is now a lot of evidence that being compassionate or kind to yourself is associated with well-being and being able to cope with life stresses. You can read more about this from a leading researcher at www.self-compassion.org.

There are important differences between self-compassion and self-esteem. For example, self-compassion is important when things are difficult or going wrong, and you are having a hard time. Self-esteem, on the other hand, tends to be associated with doing well and achieving. Self-esteem is more linked to our drive-achievement system. It often focuses on how well we are doing in comparison with others, and this is why low self-esteem is often linked to feeling inferior – as we are judging ourselves in comparison with others. Self-compassion, on the other hand, is about focusing on our similarity and shared humanity with others, who also struggle as we do.

Our brains have been designed by evolution to need and to respond positively to kindness, so it is not a question of ‘what we deserve’. It is not self-indulgence, any more than training your body to be fit and healthy is a self-indulgence. It is simple a question of treating our brain wisely and feeding it appropriately. This is really no different from (say) understanding that our body needs certain vitamins and a balanced diet. It’s not a question of whether you deserve to give your body vitamins or not, you simply do it because it’s sensible. It’s the same with kindness. It’s not an issue of deserving, it’s an issue of understanding how our mind works and then practising how to feed it things to help it work optimally. We will be looking at this as we go through the book because some people find this a bit tricky; they can even be frightened to give up their sense of being inadequate or bad in some way. However, they can practise switching to self-kindness each day and see how things go.

I’m sorry if I seem a bit repetitive here, but this is an important idea to convey: ‘depression is not our fault and there is nothing bad about us’. Indeed, evolution may have designed depression (with its reduced positive feelings and increased negative feelings) as a kind of protection when we are in a high-stress environment – like a safety switch or fuse on an electrical circuit that trips out if it is overloaded. The reason for hammering away at this idea is because some depressed people struggle terribly, feeling responsible, inferior or inadequate in some way for being exhausted or depressed. That’s why so many depressed people don’t seek help – because they are ashamed of depression. They may not even recognize it themselves.

If you can take the approach outlined here, you can see that our depressions need our compassionate understanding – to be worked with, worked on and healed as best we can. We did not design any of the mechanisms in our brain that give rise to depression – nor any of the desires that may be thwarted, and cause depression – nor the genes that might make us vulnerable to depression – nor the early life experiences that also make us vulnerable to depression. If we see this, then we also see that depression cannot possibly be our fault.

However, because the depression is happening inside our heads the question is, how can we take responsibility or be ‘response able’ – that is, come up with healing and balancing responses to our depressed brain states? Can we learn to settle down our threat-protection systems? The moment we give up self-blaming and shaming, refuse to see depression as a personal weakness or even be frightened of it (but instead see it as a brain state pattern that has been created in us), we can turn around and face it and do what we can to overcome it. Seeing that the basis of our depression is not our fault is not to say that we aren’t doing things that are making the situation worse, or that we couldn’t help ourselves more than we are. Indeed, we may need to take more responsibility for changing our behaviors, our thoughts or even styles of relating, and work our way out of depression.

We are going to be looking at many ways that we can tackle depression throughout this book, but there is a key message that I want to convey: whether you work with your thoughts or feelings or your behaviors, if you learn to do it in the spirit of support, encouragement and kindness, this will give you an extra boost to your efforts. Indeed, kindness to yourself may be one of the things that you haven’t been too good at, and one of the skills that require practice. Some of you will be frightened of that idea; you may see self-kindness as an indulgence or weakness or letting yourself off the hook, or you don’t deserve it, or you might feel that if you’re kind to yourself and enjoy life something bad will happen tomorrow; you’ve always got to pay for the good times. Or it may touch sadness in you because it reminds you that you’ve been yearning for kindness and connectedness for a long time. If you are feeling or thinking this, you are certainly not alone! Many depressed people have these types of beliefs and fears. So we are going to work a step at a time. But as I have suggested, think about self-kindness in a different way. Take a physiotherapy approach to your brain and think about exercising/training it – a kind of emotional fitness training. Self-kindness is a way to restart that soothing system and bring balance to your mind.