When we feel depressed we can feel tired and aimless; we may not be sleeping well and so feel exhausted. We can also feel physically unwell and ‘heavy in the body’ compared with our normal selves. One patient said, ‘My whole system seems stuffed with black cotton wool.’ This is because when we become depressed there are very real changes in our bodies and brains. The fact is that our brains work differently when we are depressed. Depression is as much a physical problem as a psychological one. Although we sometimes still tend to think of the mind and body as separate, they are not. The mind and body are one. Over 2000 years ago, the Greeks thought that depression was caused by too much ‘black bile’ in the body. Indeed, ‘melancholia’, another word for depression, means ‘black bile’. Although, as they were well aware, this raises another question: What causes the black bile to increase? The Greeks had rather good ideas about this. They thought that there were people who ‘by their nature’ had more black bile – melancholic types. But they also believed that stress, diet and seasonal changes could affect the amounts of black bile in the body. The Greeks recognized that we can be upset by things that happen to us and that these upsets can affect our bodily processes – that is, affect the black bile. Their approach to depression was the first truly holistic one, taking body, mind and social living into account. Today, we call this holistic approach the biopsychosocial one. This simply means that we need to understand not only the bodily and mental aspects of depression but also the interactions between our biology and bodily processes, our psychology (how we think and cope) and the kinds of social circumstances in which we live.

Today we no longer think in terms of ‘black bile’ but in terms of chemical changes in the brain and other bodily processes. However, the idea that some people are, sadly, ‘by their nature’ more prone than others to certain types of depression has been confirmed by research.1 Research has also shown that most depressions arise from combinations of early life experiences, current life events, lifestyles and the way we cope with them. Our central task in this chapter is to understand how these interact to produce the bodily and mental states of depression. The more we understand these interactions, the more sense it will make to help ourselves by using some of the methods outlined later in this book.

The brain is affected by depression in many ways. The sleep system is disrupted; the areas of the brain controlling positive feelings and emotions (joy, love, pleasure, fun) are toned down; and the areas controlling negative emotions (anger, anxiety, jealousy, shame) are toned up. In other words, when we are depressed, not only does life stop being enjoyable, but we are also more anxious, sad, irritable and bad-tempered. These changes in our feelings happen because there are changes in the way messages are relayed between one nerve cell and another in the brain.

Chemicals that operate as messengers between nerve cells are called neurotransmitters. There are very many different types of neurotransmitters in the brain. One type is called monoamines. These include dopamine, noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and serotonin. These three neurotransmitters control many functions in the brain, including appetite, sleep and motivation and are especially involved in moods and emotions. In depression these mood neurotransmitters are believed to be depleted and not working efficiently. The same may be true for transmitters that influence the soothing system and give rise to feelings of calm, safeness and peaceful-contentment feelings, such as the endorphins (natural opiates) and the hormone oxytocin.2 These are important chemicals in our brain, which are responsive to feeling cared for. A key question is: why have these changes occurred in the brain, and what can we do to help us to recover?

In fact, there are various ways in which our mood chemicals can be affected to make us vulnerable to depression. The three most important are our genes, our history and current stress. Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Genes are segments of DNA that control a vast number of chemical processes in our bodies and brains. The genes we inherit from our parents are the blueprints from which we were created. The first possibility, then, is that there is an inherited biological sensitivity to depression. On the basis of current evidence, it does seem that there is a genetic or inherited risk for some forms of depression; vulnerabilities to depression can run in families. Genes may affect the ease with which depressed brain states are activated by life events. They can also affect how we cope with life events and how we cope once we become depressed.1

We must be careful though not to draw over-simplistic conclusions from these findings, such as ‘all depressions are inherited diseases’. In the first place, much depends on the type of depression. Some depressions (especially bipolar or manic depression) do have a high ‘genetic loading’. In addition, some people have an increased risk of certain types of depression if some of their close (genetic) relatives have certain disorders, including anxiety and alcoholism. Over the years there have been studies on thousands of twins, and genes seem to affect many behaviors and personality traits right down to preferences in clothes and food! In fact recent research shows that there are a number of different genetic vulnerabilities to depression. Most of these interact with life events and early life experiences to influence whether depression occurs or not.1 However what is also very important is that research shows that even if we carry a genetic risk for certain depressions, the kind of early life we have may do much to change or even remove this risk – and the kindness we experience is key.

Although genes give us a blueprint, pathways in our brains (and our mood chemicals) develop from the experiences we have. We now know that the brain is very flexible or ‘plastic’ in this regard: it’s called neuroplasticity.3 The brain of a child who is loved and wanted will mature differently from that of a child who is abused and constantly threatened. Indeed, research has shown very clearly that love and affection, in contrast to coldness and abuse, affect the way areas of the brain that control moods and emotions develop. For instance, there is increasing evidence that many people who are susceptible to chronic forms of depression have histories of abuse, and that the stress systems of some of these people have an increased sensitivity.

As we come to recognize our own personal sensitivities, psychological understanding and training can do much to help us cope better and change our sensitivities. However, prevention is of course better than cure, and the more we understand about the role of our early relationships in how our brains mature, the more seriously, as a society, we must take childcare.

Many depressions are triggered and maintained by stress. Stress can be a source of many different psychological problems, including anxiety, irritability, fatigue – and depression.4 The way we cope with stress, too, can give rise to different psychological problems. Some people under stress are able to recognize it and back off from what is stressful to them. Others, however, are not able to escape from things that are stressful; for example, if we are in a job or a relationship that is ‘stressful’, it may not be easy just to walk away. Other ways of coping with stress may cause problems of their own: for example, drinking too much alcohol. Before we look at how our thoughts and coping efforts can make stress worse, let’s explore what happens in the body when we are stressed.

In recent years there has been growing interest in how stress (arising from the threat-protection system) works in depression. For example, one effect of stress is for adrenal glands to produce more cortisol. Cortisol is an important hormone that circulates in the body all the time, increasing and decreasing over each 24-hour period. This hormone does some useful things. It mobilizes fat for use as energy; it has anti-inflammatory properties; it is involved in the functioning of the liver; and it may also increase the sensitivity to and detection of threats. This all seems very positive and useful. When we are under chronic stress, however, the amount of cortisol circulating in the blood is increased, and it turns out that a prolonged high level of cortisol is bad for us. It is bad for the immune system (indeed, the effects of cortisol may be one of the problems in those who suffer from chronic fatigue syndrome), and it can cause undesirable changes in various areas of the brain that are involved with memory. Problems with memory and concentration may well be symptoms of excessively high cortisol levels. Cortisol also affects our mood chemicals. It can also make us hypersensitive to threats, which is not necessarily useful if it makes us focus too strongly on the threatening and negative aspects of situations and events. Research has revealed that many depressed people have highly stressed-out bodies with increased cortisol levels.

Let’s think about another important aspect of stress: control. Can we control the effect of stress on us, and what happens if we can’t?

Over 40 years ago, the American psychologist Martin Seligman found that, if animals were put under stresses that they could not control, they would become very passive and behave like depressed people. This did not happen if the animals could control the stress. These extremely important findings were later taken up by other researchers who wanted to see what changes took place in the brains of animals subjected to uncontrollable stress. It was found that some of the changes were similar to those associated with depression. For example, activity in areas of the brain that control positive emotions and behavior was reduced, stress systems went into overdrive and the mood chemicals – dopamine, noradrenaline and serotonin – were depleted. However, if other animals were subjected to the same stress but had the means to control that stress, different changes took place: the areas of the brain that control positive emotions and active (rather than passive) behavior were toned up and the mood chemicals were enhanced. This tells us something very important. The same stress, but with different levels of control, can produce quite different changes in our bodies and brains. If you are stressed and can do something about it, your brain will react in one way; but if you think you can’t do anything about it, it will react in a different way. The way you cope with stress is a key issue. Although taking control is not always easy, as we will see, there are many things that we can do to help us have more control over our lives and depression and thus influence our mood chemicals.

We often talk about ‘the last straw’ because we know that stress can be cumulative – it builds up. Take Nicky. Her firm was experiencing financial difficulties and she believed she was likely to lose her job, leaving her with a very uncertain future. The threat of redundancies had been hanging over the office for a couple of months and the atmosphere at work was very gloomy. Then, driving home late one evening, she was involved in a car crash. Responsibility for the accident was unclear, but she felt that it was partly due to a lapse in concentration on her part. She wasn’t seriously injured, but her car was damaged and she was shaken up for quite a while. As she was recovering from this, her mother had a heart attack. Nicky had not been sleeping well for a month or so, and shortly after her mother became ill her sleeping became even worse. She began to brood more and more on the car accident and her responsibility. She also thought that maybe the worry of all that had contributed to her mother’s heart attack, through stress. She felt she should do more to help her mother, but found that visiting her took up a lot of time and energy. She began to feel very low in mood, increasingly anxious and irritable, and personally inadequate; she found it difficult to get out of bed in the morning, and was prone to thinking ‘There is not much point because things just happen out of my control.’ Not being able to ‘get her old energy back’ was itself depressing.

In many cases of depression there is a combination of stresses and setbacks. There may be financial worries, worries over a job (or lack of one), conflicts at home or at work, children having problems, health worries and so forth. Over time the cumulative effect of these difficulties increases stress and edges us closer to maladaptive feedback, where we begin to ruminate on all the problems and spiral down into depression.

One of the things that many people notice as they become depressed is that small things, or things they used to do easily, like calling the garage to have the car fixed, or having friends over for dinner, or queuing in the supermarket, become filled with anxiety or are hard to do. They start putting them off, and at the same time worrying because they have not been done. Suddenly, small things become big things. If this happens, then recognize your anxiety is a normal (if unpleasant) effect of your over-stressed brain state and will settle as you get better. Try as best you can to do those small things and not let them build up and get on top of you. You will feel better for it, even though it may take a lot of effort; whereas if you do put them off, you may start to brood on them and that will increase your stress. Recognize that your experience is a common one, and doesn’t mean that you are ‘personally useless’.

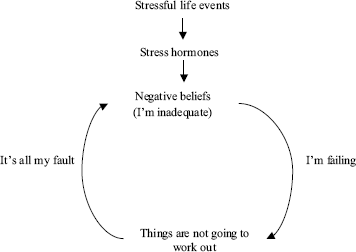

A lot of what we try to do when helping people cope with depression is to stop spirals of stress. All kinds of events can happen to us at any time. Our plans and aspirations may not be working out; our relationships may be falling apart; we may be involved in car accidents, financial reverses and health changes. Or we may simply be overworking, trying to cope with the demands of a job, children or both, caught up in the ‘hurry, hurry’ society. All these experiences can be stressful to the extent that they tax our stress systems, raise cortisol levels and deplete mood chemicals. As the amount of cortisol in our system goes up, we become more focused on the negative, more fatigued and more stressed (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Relation between stress and thinking.

There are many times in life where our decisions are not based on rationality. Falling in love, choosing this career over that one, wanting children, liking this movie but not that one, are all based on how we feel about things. Our feelings can be automatically triggered and affect how we think about things and what we do. So there is another reason why we can become more focused on the threats and losses and become locked into the kind of loops described above. Our brains are built to be irrational at times! Consider an animal peacefully grazing in an open field. Suddenly its attention is drawn to a movement in the grass. What should it do? Should it ignore it? Wait to find out what it is? Or get the hell out of there? In many cases in the wild, the best thing to do is ‘get the hell out of there’, because the movement could be a predator. In fact, the grazing animal only has to make the wrong decision (underestimate the danger) once, and it’s dead. It would be far better to run away when there was no need to than stay and take the risk. If the animal runs away it has lost some time feeding, but it is still alive.

When we are under threat, our brains have been designed to work on a ‘better safe than sorry’ principle. That is, our brains were designed not to think rationally in all situations, but at times to jump to conclusions and assume the worst, which allows a rapid response if needed. It does not matter that this jumping to conclusions could be wrong, only that it works and protects us. The strange thing about this is that it means that the brain is designed to make mistakes, especially when we are under stress: to lead us to assume the worst and take defensive action unnecessarily. It helps to recognize that when we find ourselves being irrational and assuming the worst, this is not because we are stupid but because the brain has a natural tendency to do just that – to catastrophize. Today, jumping to conclusions and assuming the worst can lead us to feel pretty miserable and lock us into stress loops (see Figure 4.1), so we need to train our minds to help us gain more control over our feelings. This is the focus of Parts II and III of this book.

It is important to note though that even though this is not our fault (because we did not design our brains like this) our thoughts can amplify the bodily stress response and affect how our brains are working. Remember the examples we used on pages 28–29. This capacity for our thoughts, images, memories and coping efforts to stimulate our emotional and physiological responses is profoundly important. When people start to work on their depression, it is not uncommon for them to say: ‘But surely my thoughts can’t make me feel so bad?’ or: ‘Surely changing my thoughts can’t make that much difference and affect my body?’ The answer is yes, they can. Of course, there is much more to depression than depressive thinking; but imagine walking around in the world thinking that you are unlovable and worthless, or focusing on how depressed you feel, or ruminating on your anger and loneliness. Very understandable, of course, but what do you think will happen to your stress and mood systems? Unfortunately, if those things go over and over in your mind, your stress system will release stress hormones. Noticing and then trying to interrupt this feedback is one of the things this book will help you with.

Of course, breaking out of the loop may not be easy. People who are vulnerable to depression may not have anyone they can ask for emotional support, or they may feel ashamed to ask. We will discuss this later; but you can see that at some point we need to break this loop that will lead into a downward spiral. If you are so exhausted that you can’t sleep and life has become very black, you may need to try some medication. But we also need to stand back and look at how we think and how we cope, and recognize how our threat-focused thoughts (natural though some of them might be) are too much in control of our minds.

So depression is not just psychological, or ‘all in the mind’, and certainly not a sign of a weak character or anything like that. Depression is about how our bodies and brains respond to stress, and about our genetic and developmental sensitivities.

Being depressed and tired can itself be stressful and depressing. If you feel ashamed of being depressed, remember that you did not design your body to respond in the way it does – you’d much rather not be stressed and depressed. If you don’t like the term ‘depression’ then tell yourself you are exhausted or burnt out or in cortisol overdrive, and seek help – but recognize that there are things you can do to help you regain some balance in your three systems (see page 17) and bring your stress spirals under control.