If you have managed to use the self-regulation and self-management techniques described in this book, you may already have been able to reduce the severity of your mood swings, or even prevent an episode of mood disorder. Controlling the symptoms that have disrupted your life is certainly important. However, your well-being is not defined simply by greater stability in your mood or the absence of symptoms of mood disorder. The next step is to overcome problems that prevent you from feeling at ease with yourself and in your relationships. Further, you will need to feel confident that you can cope with day-to-day problems and have a sense of where your life is going.

The final chapter of this book aims to help you to begin this process by looking at your view of yourself, aspects of your relationships with others, and some of your day-to-day problems. Much of this discussion focuses on coping with the aftermath of previous mood swings or episodes of mood disorder. Lastly, it looks at setting goals for your future and suggests additional tips on how to be your own cognitive therapist.

When you feel down, it is common to have negative automatic thoughts about yourself. However, some individuals report that they never feel totally at ease with themselves. This low self-esteem or lack of self-confidence may be a lifelong characteristic, predating any mood swings; or it may have arisen as a consequence of having repeated severe mood swings and difficulties in coming to terms with behavior during these episodes. In reality, many individuals with mood disorders have a long-standing fragile self-esteem that is further undermined by experiencing mood swings. There are a number of approaches to overcoming low self-esteem, and a detailed account can be found in Melanie Fennell’s book in this series, Overcoming Low Self-Esteem. Later I will outline some useful ways to begin the process, but first it is important to identify unhelpful strategies that in the long term appear to have more disadvantages than advantages.

If you lack self-confidence to start with, and then have repeated experience of mood swings, it is easy to understand why you might employ various strategies to put painful thoughts about yourself at a distance. Unfortunately, there are some approaches that don’t help individuals to cope effectively on a day-to-day basis. The three strategies that do not seem to help improve self-esteem are:

• trying to avoid thinking about what happened;

• trying to externalize the responsibility for the way you feel;

• trying to convince yourself that being slightly high will overcome your negative view of yourself.

Unhelpful strategy 1: avoidance – “If I don’t think about it, it’ll go away.” It is tempting to avoid thinking about previous episodes of mood disorder and refusing to look at any adverse consequences of your actions, for you or for others. While avoiding thinking about issues that make you feel unhappy about yourself may help you for a short time, there are two major problems with this approach. First, you are missing an opportunity to work out how to solve your problems and to reduce the chances of the same problems cropping up in the future. Second, to avoid thinking about what happened may mean avoiding any discussion or contact with individuals who knew about it and might comment. This will inevitably restrict your lifestyle and may actually mean you lose contact with some sources of support. In the long run, this may worsen rather than improve your self-image.

Unhelpful strategy 2: rejecting all responsibility – “It’s not my fault.” You are not 100 per cent responsible for some of your actions when you are unwell. There are times when individuals with mood disorders are clearly no longer able to control their actions and responses. However, it is equally true that you cannot reject all responsibility for what happens to you. No matter how many other factors play a role, shifting the responsibility to “the illness”, other people, mental health professionals, the hospital or the treatment, without exploring what you may be able to do to help yourself, is counterproductive.

If you subscribe to the view that everything in life is totally beyond your control, you are in danger of giving up on your future. This would be a tragedy, as there are many areas of your life that you can positively influence. Furthermore, establishing what you can control will help you develop a more positive view of yourself. For example, you are not responsible for the fact that you get mood swings, and you may not be able to stop them happening. However, you may be able to learn how to recognize your problems early and seek help before your symptoms progress to a dangerous level. In addition, you can control other aspects of your life in spite of your mood swings.

Lastly, blaming everyone or everything else is unhelpful to your self-esteem. Even if other people or services have not always acted in your favour, you cannot expect to control how they react in the future. Ultimately you can only be sure of changing your own role or actions. The important aspect is to understand what you can control and what you cannot, and to be clear about your responsibilities and those of others. As discussed later in this chapter, your degree of responsibility will rarely be either 0 per cent or 100 per cent.

Unhelpful strategy 3: “Who am I?” – basing your self-image on how you are during your highs Individuals who experience mania often think that their ideal “normal” state is not euthymia but the early stages of a high. At this point they feel more productive and active, and often get positive feedback from those people around them who do not know that they have a mood disorder. Alas, basing your self-image on a temporary state is unrealistic and unhelpful, for two reasons. First, there is a danger that you are focusing only on the good aspects of highs – what about the disadvantages? Don’t forget that the early stages of a high do not last for ever. This phase usually leads to a manic episode or to a depressive swing. Both outcomes have considerable negative effects for you or for other people. Second, positive feedback or admiration from others will not last if those individuals also see you when you are so high that your thinking becomes chaotic, your mood unpredictable, and your actions erratic. Their views of you will start to fit into the “yes, but” category: “Oh yes, he’s capable of a fantastic work rate and can be the life and soul of the party; but sometimes he really loses control, the quality of his work deteriorates, and he goes too far and upsets lots of his colleagues.” A reputation of this kind is unlikely to help you feel positive about yourself.

Having highlighted some unhelpful strategies, we will now focus on approaches that may lead you in the long term to a more positive and stable view of yourself. To begin with we need to review the way you see yourself now, then look at how to cope with any negative consequences of recent mood swings.

The first steps in building up your self-esteem are

• to develop a realistic view of yourself;

• to reduce your over-dependency on others’ opinions;

• to try to build a positive self-image.

Trying to develop a realistic view How well do you know yourself? You may feel bad about yourself, but, as we have discussed on many occasions earlier in this book, these feelings are often associated with negative automatic thoughts. To try to clarify in your own mind where any negative feelings come from, and how accurate any negative thoughts are, it is helpful to draw up a list of your personal strengths and weaknesses (a blank table for this purpose is provided in the Appendix on p. 243). To get started, here are a few questions that may help you:

• What do you like/dislike about yourself?

• What positive/negative qualities do you possess?

• What do other people like or dislike about you?

• How would others assess your strengths and weaknesses?

• What qualities do you like/dislike in other people? Do you share any of these qualities?

Try to be honest with yourself and to give equal attention to each question. Also, try to avoid global labels such as “I’m a terrible mother” or “I’m useless.” Even if you have such negative thoughts, try to be specific about why you have made this statement. This means exploring the evidence. For example, “I lost my temper with my children over nothing,” or “I have failed to deliver on promises I made to people.” Now try to check whether the list contains any statements based on single events or experiences. Are you certain these represent persistent personality characteristics? If not, why do you think they should be included (you may have a particular reason)?

Next, explore whether you have any evidence to support each statement on your list. If not, can you justify including this item on your final list? When you have reviewed and revised what you have written, ask yourself the following questions: What do you learn about yourself from your list of strengths and weaknesses? If you showed this list to someone you trust or who knows you well, would they agree that this is a realistic appraisal? If you are not sure, could you ask them? Finally, can you write a two- or three-line summary about yourself? Try to identify your key strengths and weaknesses, and start your description by noting your good points. For example, “I am reliable and hardworking and people like my sense of humour, but I can show a low tolerance of frustration and sometimes expect too much of others.”

You cannot change your self-esteem overnight. However, by working on the list, you can begin to explore the following themes:

• How can I build upon my current strengths?

• How can I reduce the frequency of any negative actions or thoughts related to my weaknesses?

• Which weakness is the best one to start working on?

• What new, positive attitudes can I introduce to build further upon my strong points?

Focusing on these issues will help you feel more confident about who you are, and encourage you to begin to like yourself a little more.

Avoiding self-criticism As well as developing a more accurate view of yourself, it is helpful to look at how you assess yourself on a day-to-day basis. By all means set yourself realistic and acceptable standards, and by all means assess whether you have lived up to your expectations. However, try not to be overly self-critical. There is a myth that self-criticism motivates people. My clinical experience is that it does the opposite. Individuals who constantly find fault with their own actions become demoralized and find it hard to keep going in the face of increased stress. Making constructive and encouraging self-statements, on the other hand, can help you achieve your goals.

To overcome self-criticism, see if you can reframe your criticisms into more helpful statements that encourage you, rather than demand that you do certain things. If your internal critical voice is very powerful, imagine that it is a parrot sitting on your shoulder that is making these criticisms. I often suggest this to people in my clinics, and I then ask them what they would do about the parrot. The more generous ones say they would make it fly away; those who are really fed up say they would shoot it. Whichever method you personally prefer, the goal is simple: silence the internal critic!

Don’t be over-dependent on the views of others Some individuals, rather than experiencing persistent low self-esteem, say that their self-image varies purely on the basis of the feedback they get from other people. Fluctuating self-esteem is as damaging as continuously low self-esteem, as it makes you vulnerable to more extreme mood swings. While you should not ignore all feedback from others, it is important to see these comments in context. Ask yourself three questions:

• First, on a scale of 0 to 100, how sensitive are you to the views of others?

• Second, on a scale of 0 to 100, how critical are others of you?

• Third, do you give equal attention to positive and negative feedback?

If you explore your answers to these questions, you may be able to judge whether you are too vulnerable to other people’s opinions, particularly critical comments.

If you are sufficiently clear in your own mind about your strengths and weaknesses and your sensitivity to criticism, you will be better able to evaluate the comments others make about you. Positive feedback will confirm your good points and negative feedback, although painful to hear, should not be too much of a shock. Remember that it is important to keep a balanced and realistic view. Don’t overemphasize positive comments; by all means be pleased, but keep your feet on the ground. Getting too carried away could simply set you on the path to a high. Likewise, don’t catastrophize about negative comments. Even if those comments are presented in a critical way and are difficult to accept, try to work out what that person is trying to tell you. Is there a grain of truth in their comments that you can learn from? Lastly, remember that your reaction to others’ comments will be largely dictated by your automatic thoughts. You can manage your feelings by following the classic approaches for modifying such thoughts, starting with an examination of the evidence supporting or refuting the idea.

Test out alternative beliefs If the techniques outlined above do not help you develop a more realistic self-image, it may be that you are overly influenced by a fixed negative belief about yourself. If you are not sure whether this is happening, it might be worth re-reading the section on underlying beliefs and how these can influence your life (p. 40–50). You may also be able to identify beliefs you hold about yourself by reviewing your automatic thought records. Are there any particular themes to these thoughts that point toward a fixed view of yourself? Can you capture the belief in a few words, by completing the statement “I am . . . ”? If you can identify a core negative belief about yourself, can you rate (on a 0 to 100 scale) how strongly you subscribe to that idea? Next, can you provide all the evidence from throughout your life that supports the accuracy of your negative view? What about evidence that goes against your belief? Reviewing this information, is this a realistic appraisal, or have you accepted this belief as true without ever thinking to challenge it?

Most individuals who take themselves through this series of questions find that their beliefs about themselves were based on relatively unreliable evidence. Knowing that your own belief is unhelpful will undoubtedly help you predict situations or events that you will find stressful. However, this information alone will not change how strongly you subscribe to this belief. It takes several months (probably about four to six) to start to change your underlying view of yourself.

The first step is to agree to explore the alternative view of yourself. For example, if you hold the belief that “I am unlovable,” rewrite this belief on a piece of paper as “I am lovable.” If you hold the belief “I am incompetent,” rewrite the statement as “I am competent.” Having reframed the statement thus, rate on a 0 to 100 scale how strongly you subscribe to this new belief. The likelihood is that you will give this alternative belief a very low rating. This is understandable, for throughout your whole life so far you have unwillingly collected information to support your old view. However, from today, you have to try to collect and record any piece of information, no matter how small, that supports the new belief. Don’t bother with the evidence against your new idea; you’ve been attending to that for years, and could fill a textbook with it!

The whole point of this exercise is to raise your awareness of any information in the environment that starts to support your alternative belief. Also, remember you are not aiming for perfection. It is unlikely you will ever believe 100 per cent that “I am lovable.” However, you may conclude that some individuals find you lovable most of the time. Likewise, being totally competent is unrealistic; try to aim for an acceptable and reasonable level of competency. A blank “alternative belief” schedule is provided in the Appendix on p. 244.

Having worked through the exercises just described, many individuals find that any remaining negative views of themselves are largely dictated by problems in coming to terms with the consequences of severe mood swings or episodes of mood disorder. They feel robbed of their future, are ashamed of some of what they are, and feel stigmatized because of their ill health. The key to coping with these problems is to try to minimize the trauma associated with the changes that you feel have been imposed on your life. Again, it is unhelpful simply to avoid thinking about these issues, or to get angry. It is more productive to start self-help and deal with the consequences as best you can.

Grief and loss Some individuals experience severe mood swings or a mood disorder that disrupt their functioning so gravely that they are no longer able to complete college courses or carry on in their employment. These unexpected restrictions not only affect their immediate activities, but may also change their career prospects and/or the future course of their lives. Many who have had such an experience feel they have become different people, and grieve for their “lost selves”, the people they used to be. This is both common and understandable. These experiences can be compared with bereavement, and are compounded by the very real losses that can be associated with having a significant mental health problem, such as loss of income or status. Others find that there are major tensions in their personal lives, sometimes leading to the break-up of important relationships.

If these things happen to you, there is no benefit in trying to underplay the difficulties created by your recurrent mood swings. You will need time to recover from your disappointments, to adjust to your new situation, and to move forward. There are a number of key steps that will help you begin this coping process:

• Try to be clear about which problems are genuinely related to mood swings. As with any grief reaction, the real losses will take time to come to terms with. Don’t complicate the process by overgeneralizing (as described in the section on thinking errors on p. 48–9) and attributing every negative event in your life to your mood disorder. For one thing, this is unlikely to be 100 per cent true; but more importantly, it is unhelpful, and will increase the risk of your giving up on your future.

• Avoid focusing on the “unfairness” of life. Life certainly is unfair in many ways; but it is unhelpful to spend too much time concentrating on something you can’t change. Preoccupation with what has already occurred may simply feed your anger and prevent you implementing strategies that help you move forward.

• Don’t pretend it hasn’t happened. Avoidance of this kind is likely simply to store up problems for the future. At some point you will have to examine what has happened, and what you can do to improve your situation. The problems will not disappear if you ignore them.

• Another way of avoiding the reality is to label yourself as the “illness”. For example, avoid introducing yourself as “I’m a manic depressive.” Don’t deny the problem, but try to remember that there is more to your identity than a mood disorder. Sometimes you will need to remind yourself of this, and it is important to make others aware of it as well.

You will not overcome your grief or sense of loss with these strategies; but they will create the right conditions for you to start the process of adjustment.

One other loss that needs to be mentioned is “missing highs”. Many individuals report that they are only too glad to be free of depression, but genuinely miss the buzz that they get from a high. As discussed earlier in this chapter, it is important to replace an unrealistic existence with a realistic one. However, like an addiction to a drug, your highs will not be easy to give up simply because it seems a sensible idea. You might like to try to reduce your dependency on highs by using a step-by-step approach similar to a “harm reduction” programme, making gradual changes to the degree of upswing in your mood that are acceptable – for example, you might start by only agreeing to take action when your mood rating is +4, then gradually move toward taking action at +3 and finally at +2 (or the agreed boundary between your normal and abnormal states). You will also need to look carefully at how to compensate for the loss of this experience from your life. For example, what activities or roles can you take on that give you a similar positive feeling about yourself?

Shame and guilt A common reason why individuals struggle to move forward is that they feel guilty about the way they used to behave or are ashamed of themselves. Greenberger and Padesky, in their book called Mind over Mood, point out that guilt and shame are closely linked emotions. Both are usually associated with a belief that we have violated our own rules about how individuals should behave, that we have failed to live up to our own standards or have been disgraced in the eyes of others. Coping with these thoughts and emotions is difficult; as with other problems we have discussed in this book, the starting point is to acknowledge to yourself what has occurred and then to evaluate the facts of the situation.

First, try to give yourself some positive feedback for choosing to face the problem and not avoiding it. When bad things happen it is easy to understand why the last thing you want to do is think about them. However, it is equally unhelpful to let any negative thoughts go around and around in your mind. Try to take a problem-solving approach and focus on what you need to do about what happened.

The second step is to record on a piece of paper exactly what occurred – what was the event that makes you feel guilty or ashamed. Greenberger and Padesky suggest that you then list everything and everybody who contributed or might have contributed to this outcome. Put yourself at the bottom of the list. Next draw a big circle on the paper. Starting at the top of the list, divide the circle up into segments of different sizes according to the degree of responsibility that should be attributed to each circumstance and each person involved. The greater the responsibility, the bigger the piece of the pie. (A blank template is provided in the Appendix on p. 245.)

Having done this exercise, consider how much of the responsibility is yours and yours alone. Do you share responsibility with anyone else, and/or did your mood disorder play any part in the event? If you are not totally responsible, does this change how badly you feel about what occurred? Is there anything that you can learn from this experience, or anything that you can do to overcome any difficulties that have occurred?

If the “responsibility pie” suggests that you shoulder most of the responsibility, examine the details of what happened and try to answer the following questions:

• How serious was the incident? Does my assessment concur with that of other people? (If others think it is less/more serious, can you determine why that is?)

• If some one I cared about had acted this way toward me, how would I view the situation?

• In the longer term (e.g. in six months, in six years), how important will this incident be?

• When I acted in that way, was I aware of the consequences?

• What have I learned and how can I avoid similar incidents in the future?

• What damage has occurred because of what I did?

• What can I do now to start to repair the damage?

• Can I predict (accurately) some of the likely responses of individuals to my attempts to repair the damage? What strategies can I use to help me cope if they are finding it hard to forgive me? What will I do to cope with my own reactions/disappointments?

It is important to try to work through these questions before doing anything. However, don’t fall into the trap of becoming more and more negative about yourself. If this starts to happen, you can try to tackle your automatic thoughts; alternatively, try to focus on a “task-orientating” statement such as “Doing a bad thing does not prove that I am a bad person” or “Having done a bad thing in the past does not mean I cannot change how I act in the future.” You may wish to talk through with a trusted confidant any actions you think might repair the damage. Getting feedback at this stage may increase your chances of achieving a successful outcome.

Stigma Many individuals feel that their status in society is undermined by the negative views about mental health problems expressed by the public at large. Alas, these prejudices do impact on the lives of many people and will not be removed overnight. But, as you cannot control what others believe or how they view mental health problems, it is unhelpful to target all your energies on them. I am not saying you don’t try to play your part in tackling stigma, but the first action that is required is to focus on whether you hold any prejudices against yourself. If you are a perfectionist, do you now see yourself as “defective”? If you have a desire to be liked or approved of by others (and most of us do), do you fear that you will be rejected? Does this fear of rejection turn from sadness into anger? If these ideas are operating, you may need to review your own beliefs and think about how to tackle the disappointment you feel about yourself. This will probably start with a review of methods of improving your self-esteem. Also, remember that anger often arises as a secondary reaction; you may need to work on the primary emotion, which may be hurt or sadness.

Clearly it is not possible to deal with all aspects of interpersonal relationships in this short section; the topic has after all been the subject of many books on its own. However, I will briefly comment on three areas that are worth considering:

• communication problems;

• assertion;

• sharing responsibility, including working with professionals.

Most of the time, we pay scant attention to the process of our interactions with other people. However, it is important to try to understand this process, particularly if you wish to pre-empt problems in relationships. Here are some guidelines for tackling inter-personal problems:

• Take your time to think about what you need to say and what issue you are trying to get across.

• Be clear and specific about the problem, but make sure you own it. Avoid placing all the responsibility on the other person. Stating “You’re ruining our relationship” is too general and seems to be blaming them. It may lead to the other person defending themselves against a perceived criticism, or angrily suggesting that you “sort yourself out”.

• Avoid sweeping statements. “Always” and “never” are key words to ban from the conversation. Other unhelpful statements include “If you loved me you would . . . ” or “If you cared about me you wouldn’t have . . . ”.

• Try to develop a shared view of the problem. If you don’t agree on the problem, you will never agree on the solution.

• Be a good listener. Don’t interrupt people and don’t tell them they’re wrong. Remember they are expressing their opinions or feelings.

• Retain your perspective. If the conversation is getting heated, be prepared to negotiate some time out so that both of you can review where the conversation is going and can steer it back on track.

• Try to stay calm. If you get angry, you may begin to use words you regret. Likewise, if you are very distressed, it is hard to come to a shared view of what to do next.

• Try to take a step-by-step approach to any agreed action, and set a time when you can both discuss the progress you have made.

• Give to get. Be prepared to play an active role in finding the solution, even if this means giving something up. Don’t expect the other person to “give to get” or to do all the giving.

• Be willing to try a solution suggested by someone else; don’t simply push the other person to follow your proposed course of action.

You will not manage to follow these guidelines all the time, but if you bear these ideas in mind you may get nearer to a solution than you have in the past. Lastly, don’t be afraid to suggest that you jointly seek help. This is particularly true if you are both struggling to overcome negative or distressing feelings, or if it is not possible to reach a shared view of the problem or the solution. A third party can often help keep a situation calm and help you focus on expressing your views in a constructive way, rather than falling into the trap of attacking the views expressed by someone else.

Assertion is one aspect of clear communication. If you have ever been on the receiving end of someone’s anger, you will know that anger rarely helps solve a problem. For a start, you may feel unsettled or quite frightened, and second, it’s usually difficult to focus on or understand what the person is trying to say. So expressing yourself through anger is unlikely to help you get your need met. At the other end of the spectrum, it is equally true that you can end up feeling very frustrated or unhappy if you find yourself doing things you did not wish to because you failed to speak up and state what your needs were.

Basically, expressing you views either too forcefully or too meekly leads to problems. To strike the right balance, you have to learn to express your preferences clearly and calmly, and to negotiate with others effectively. The basic rules of assertion are:

• Have respect for yourself and recognize your own needs.

• Be prepared to ask for what you want.

• When expressing your opinions or feelings, always use “I” statements.

• If you are unsure about a proposal, ask for time to think it through; avoid being pressured into instant decisions.

• Remember that you can change your mind, but if you do, try to give people clear warning and an explanation.

• Recognize that you are responsible for your own actions, but that you cannot completely control those of other adults.

• Respect that other people have the right to apply the same rules of assertion to their own situations.

Getting this process right takes time. Practice helps, particularly if you have been prone to getting angry in the past, or have lacked the confidence to express your own needs.

We noted earlier that at some point you may wish to repair any damage done to relationships as a consequence of behavior that occurred during your mood swings. This conversation often begins with you accepting a lot of the responsibility, or for not acting sooner to avert problems. However, this dialogue also allows you to hear other people’s opinions on what they may be able to do to help. Rather than instantly rejecting the opportunity to have others involved, take time to think about the advantages and disadvantages. Are there any benefits in their playing a role in helping you overcome your mood swings? Can they help you with any of your other problems? Will it actually improve your relationship if a particular person has a greater understanding of your problems and a clear role in supporting you? No one can make you accept any of these offers, but it is worthwhile considering the pros and cons. There is no rule that says you should always cope on your own.

A special case in sharing responsibility relates to how you work with health care professionals. Many individuals with mood disorders report enabling and collaborative relationships; others are disappointed. The frustrations of the latter often relate to thoughts that the doctor or professional they are in contact with does not have a clear understanding of their own situation, problems, and needs. If you hit problems, try to remember that this is a clash between two experts. You are an expert on how mood disorders affect you. You have a depth of knowledge about your own special circumstances that it would be hard for anyone else to attain. The other person is an expert on mental health in general and will have seen many individuals with similar (but not the same) problems associated with mood disorders. They have a breadth of knowledge about mood disorders that you may never develop. Sharing responsibility means that you are both clear about the aims of treatment and are both working toward the same goals. In this relationship, you are entitled to respect, information, and choice. In return, you must try to respect the other person’s opinion and the advice they offer. Sharing the knowledge you both have and then coming to an informed decision is worthwhile, but can be very hard work for both parties. Remember the guidelines for communication also apply to this situation!

You will probably have at least a vague sense of where you would like to be in the future, and some views on how you would like your life to be. If you are to turn these aspirations into tangible goals, you have to be able to describe them in more specific terms and also to determine how realistic the goals are. To help begin this process try to complete this statement:

“I will know that I am well when I am [doing the following . . .]”

This approach is similar to that used to create your symptom profile, but you are now trying to develop a well-being profile. A template is provided in the Appendix for you to complete (p. 246). Some individuals prefer to divide the list into separate areas, such as: basic day-to-day functioning (e.g. “I will be in full-time employment”); interpersonal functioning (e.g. I will have developed a social network”); view of self (e.g. “I will be at ease with myself”).

Having created this profile, identify which issues you are already working on and which still need to be acted upon. You may wish to list these outstanding issues in order of priority. It is helpful to start with any basic problems, particularly those relating to the aftermath of any recent mood swings. Next, check that each item on the list is written as a goal rather than a problem. For example, financial problems can be defined as a goal to “reorganize my monthly spending and set money aside so that I can pay off my overdraft by June 2002”. This goal demonstrates two key components: first it is specific; and second, it sets a clear target. The next questions you must ask are: “Is my goal realistic; is it achievable?” The final question is: “How will I measure my progress?” In the example given, you might set sub-goals for how much of your overdraft you will pay off per month, or how much will be paid off during each six-month period.

Once you have identified a specific, realistic, and achievable goal and know how you will measure your progress, you next need to establish the steps required to achieve this goal and then to set an appropriate time-frame. To generate the steps, try to use the problem-solving techniques described earlier. If the goal is likely to take some time to achieve, for example returning to full-time employment, you may also wish to set some sub-goals. These sub-goals represent important steps along the way to your target. They also allow you to further divide the task into more manageable units and to detail the steps required between each sub-goal. You can then assess how far you expect to get in the short, medium, or long term.

As well as working out a detailed action plan, you will also need to identify any obvious hurdles or barriers to achieving your goal, and brainstorm a list of the potential ways to overcome those problems. Finally, set a specific time to start working on the first step toward your goal, and note the cues that will keep you on track and focused.

To help you gauge whether you have understood this approach, you may like to work through the following example:

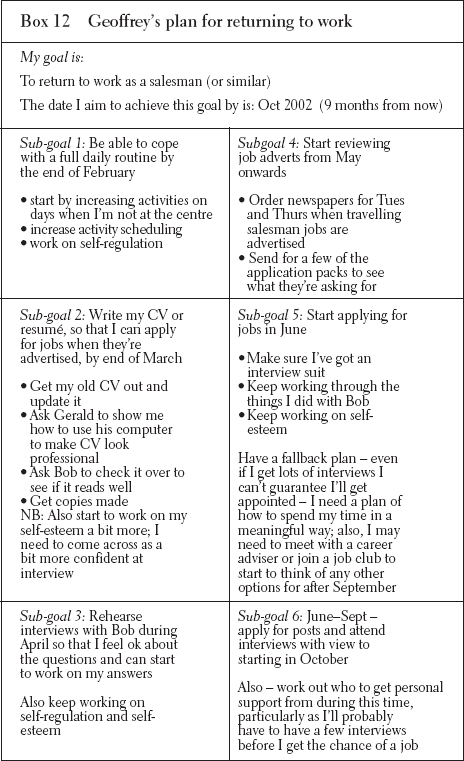

Geoffrey has recently recovered from a depressive episode. He has been able to use a number of self-management strategies to cope with his problems and is feeling more optimistic about the future. He currently attends a day centre two days a week, but has difficulty filling the rest of his time. He wants to return to full-time employment as a salesman. He realizes this will take some time, so he identifies his future goal as: “To return to full-time employment as a salesman or in a related job, within nine months.”

Can you describe the course of action Geoffrey might take? After you have tried to do this, you may like to compare your approach with the plan I have described in Box 12. Obviously, there is no absolute right or wrong way to tackle the problem, and your version may differ from mine. Whatever your chosen route, try to remember to describe every step you think is required in detail. A good test is whether someone who read your plan could follow it and reach the desired endpoint. If not, which parts have you identified in your mind but not written down?

If you feel comfortable with this approach, you may like to work through your own list of future goals and begin to describe the action plan for each of them. A template for pursuing this idea is provided in the Appendix on p. 247.

One of the issues raised in the discussion of future goals above was the need for cues that will help you keep on track. It is only human to show some variability in your commitment to working on a personal target. Like many other people, you may find you are more interested in applying self-help strategies when you have symptoms or problems. Your enthusiasm to write notes, tackle automatic thoughts, or work on other issues may recede if you are feeling a bit better and do not see any immediate difficulties on the horizon. However, it is worth thinking about how you can tackle this natural tendency and gain the maximum benefit from the approaches we have discussed. If there were a therapist present, they would probably alert you to three issues:

• doing the basic minimum to maintain your current state;

• dealing with setbacks;

• scheduling therapy sessions regularly.

If you mood is stable and you have no immediate goals you wish to work on, should you give up using self-help? The obvious answer any cognitive therapist would give is no. However, you may be able to tailor the use of the techniques to fit in with your preferences. There are two elements to this strategy.

First, don’t stop using all of the techniques. The interventions that got you well will help keep you well. Hence it would be foolish to stop self-regulation or any key approach that has really been of benefit. Try to identify the minimum number of techniques you are prepared to continue using, and then push yourself to keep them going. This is important as you need to feel able to increase the use of these or similar techniques in response to change. Lack of practice may reduce your confidence in using the technique when under stress.

Second, there is a minimum set of commitments that you should try to make in order to maintain your well-being:

A: Awareness of the key features of your mood swings and the associated symptoms and problems.

R: Recognizing your relapse signature or when your problems are escalating.

T: Taking early action to deal with problems or potential relapses, including seeking help from others.

This approach is described as the ART of well-being.

It is unlikely that you will go through all the approaches in this book and never hit a problem or setback. Try not to panic or catastrophize; stay as calm as you can, and reflect on what has happened. Next try to work through the following steps:

• Using notes you have made or information in this book, try to determine how this setback has arisen and how you might cope with it.

• Write down any techniques that you might use at this moment, e.g. activity scheduling, calming activities, problem-solving.

• What negative automatic thoughts may be contributing to how you are feeling?

• Can you write down any automatic thoughts, and can you challenge the most powerful thoughts?

• What underlying beliefs may have been activated?

• Are there any behavioral or cognitive strategies that you could use to help you cope with this situation?

• Can you list the range of interventions that you could try?

• Can you put these in order of priority and begin with the first approach on the list?

• If none of the above approaches seem to help, who can you talk with to help you deal with this problem and how it has made you feel?

Try to take a problem-solving stance to a setback; giving up is not a helpful approach, no matter how strong your wish to stop trying. Dealing with any negative thoughts and feelings is particularly important, as this may clarify what the real issues are and allow you to work out what steps you need to take next.

If you were engaged in a course of cognitive therapy you would probably have a regular appointment to see your therapist that you had both agreed in advance. One way to keep focused when working on your own is to schedule appointments with yourself! For example, rather than reviewing progress on self-regulation in an ad hoc way, you set time aside every week to monitor your progress and review what to do next. Fixing a time each week is also a way of valuing yourself and looking at your own needs. If self-help approaches are important to you, you owe it to yourself to find a reasonable amount of time to devote to them to increase the likelihood of making them work for you. Merely fitting any review into a spare ten minutes at the end of a tiring day is not giving yourself the best chance of benefiting from the approaches.

If you decide to plan some appointments with yourself, try setting aside about 45 minutes on a regular day each week. Next, try to set an agenda for the session, so that you are clear what aspect of your self-help programme you want to review. A typical schedule is described in Box 13. Obviously, you may not wish to address all the questions listed here; this template can be adapted to your own needs and preferences. It is worth retaining the same items at the beginning and end of the session: that is, start each week with a review of progress since the previous week and end with a clear set of tasks for the next week.

Box 13 Possible agenda for sessions with yourself

Date:

Current mood ratings:

Possible agenda items

1 Review tasks set last week and write a few sentences on what I have learned.

2 What symptoms or problems do I have currently?

What techniques can I use to deal with them?

3 What goals do I have?

Am I making progress?

What barriers have I encountered or do I need to be aware of in the coming weeks?

What skills do I have to overcome these problems?

4 What areas still keep me vulnerable?

5 What areas do I still need to work on and how am I going to do this?

6 What tasks do I need to address in the coming week?

What can I do if I encounter any setbacks?

Write brief notes on the session and ensure time is set aside in diary for next session.

As with any therapy, you may be able to spread out your sessions as you feel that the cognitive and behavioral strategies become second nature. However, if you always find an excuse for not doing your sessions you may also like to explore the thoughts that are linked to your reluctance.

I hope that this final chapter has given you some ideas about how to move forward in the future. The cognitive and behavioral strategies that may reduce the risk of further mood swings can also be applied to other aspects of your life. Remember, it is more constructive to regard each attempt to use these techniques as an experiment rather than as a test to be passed or failed. Be kind to yourself if you can’t always follow the plan you have set at first. Getting rid of the internal critic and setting the other conditions for improving your self-esteem are important initial steps. This will allow you to address your future goals in a more positive and realistic frame of mind. Finally, remember that the key to overcoming mood swings is being clear what your own responsibilities are in dealing with these problems and then learning to control what you can control.

Summary

Looking to the future with confidence requires the following:

• Overcoming low self-esteem through:

– developing a realistic appraisal of your strengths and weaknesses;

– reducing self-criticism;

– reducing reliance on the views of others;

– testing out alternative views of yourself.

• Overcoming poor self-image that arises as a consequence of mood swings by trauma minimization – applying personal first aid to deal with:

– grief and loss;

– guilt and shame;

– stigma.

• Developing strong relationships through:

– clear communication;

– asserting yourself;

– sharing responsibility if you choose.

• Developing life goals that are;

– specific and realistic;

– clearly defined in terms of steps or sub-goals;

– recorded on a time schedule.

• Being your own CBT therapist, which may include the following:

– subscribing to the ART of well-being approach

A: awareness of mood swings;

R: recognizing symptoms and problems;

T: taking early action;

– dealing effectively with setbacks;