HOW TO READ A PROTEST

Protests work—just not, perhaps, the way you think.

When you’re in the midst of a demonstration, especially a very large one, the sense of collective power is stirring and immediate. There’s a great feeling of purpose and unity when you stand with a huge crowd of other people who share your outrage over an injustice and your eagerness for action. Joining a protest, whatever the cause, gives you the direct bodily experience of being part of something larger than yourself. In a literal and immediate way, you add your heart and your voice to a movement.

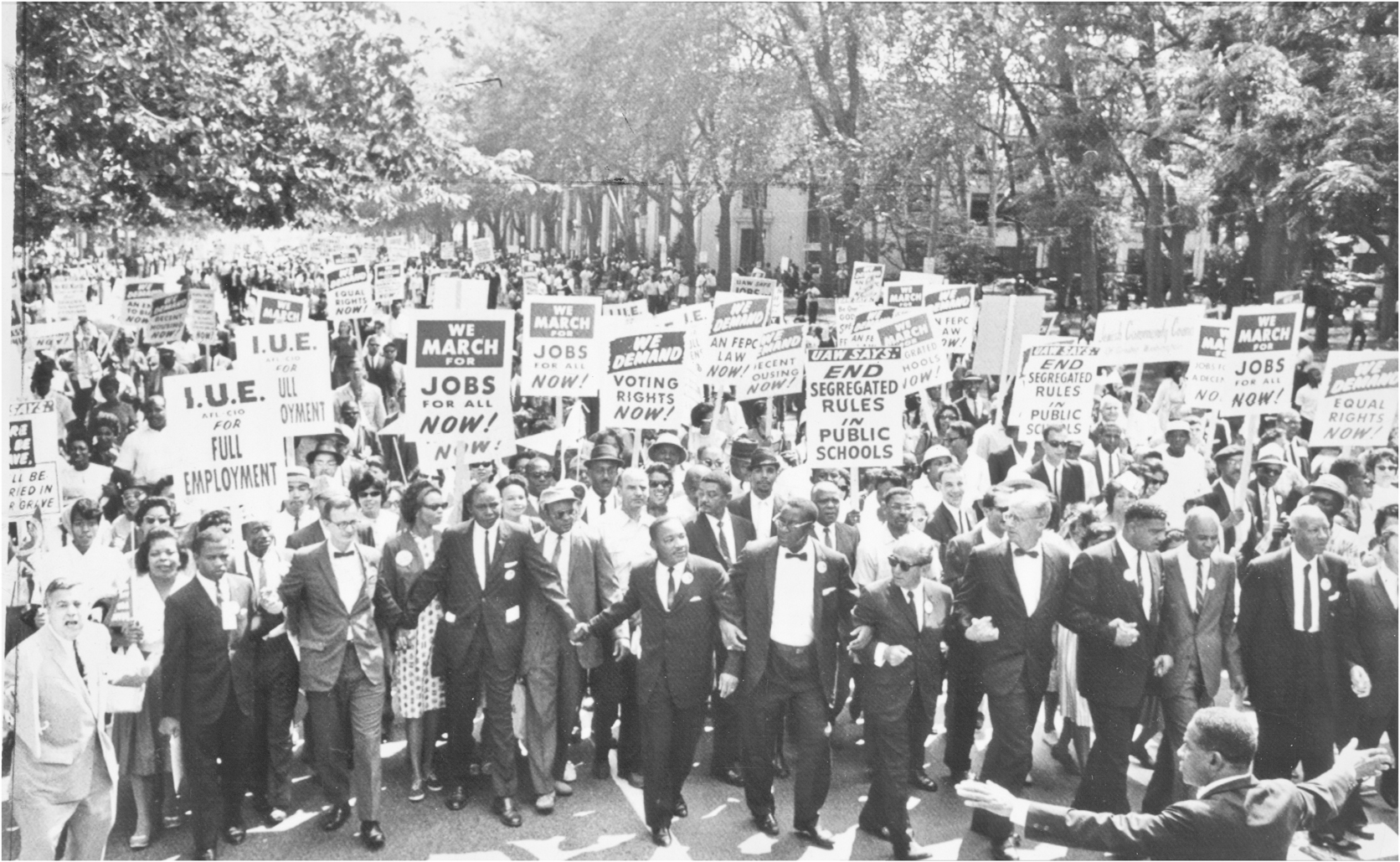

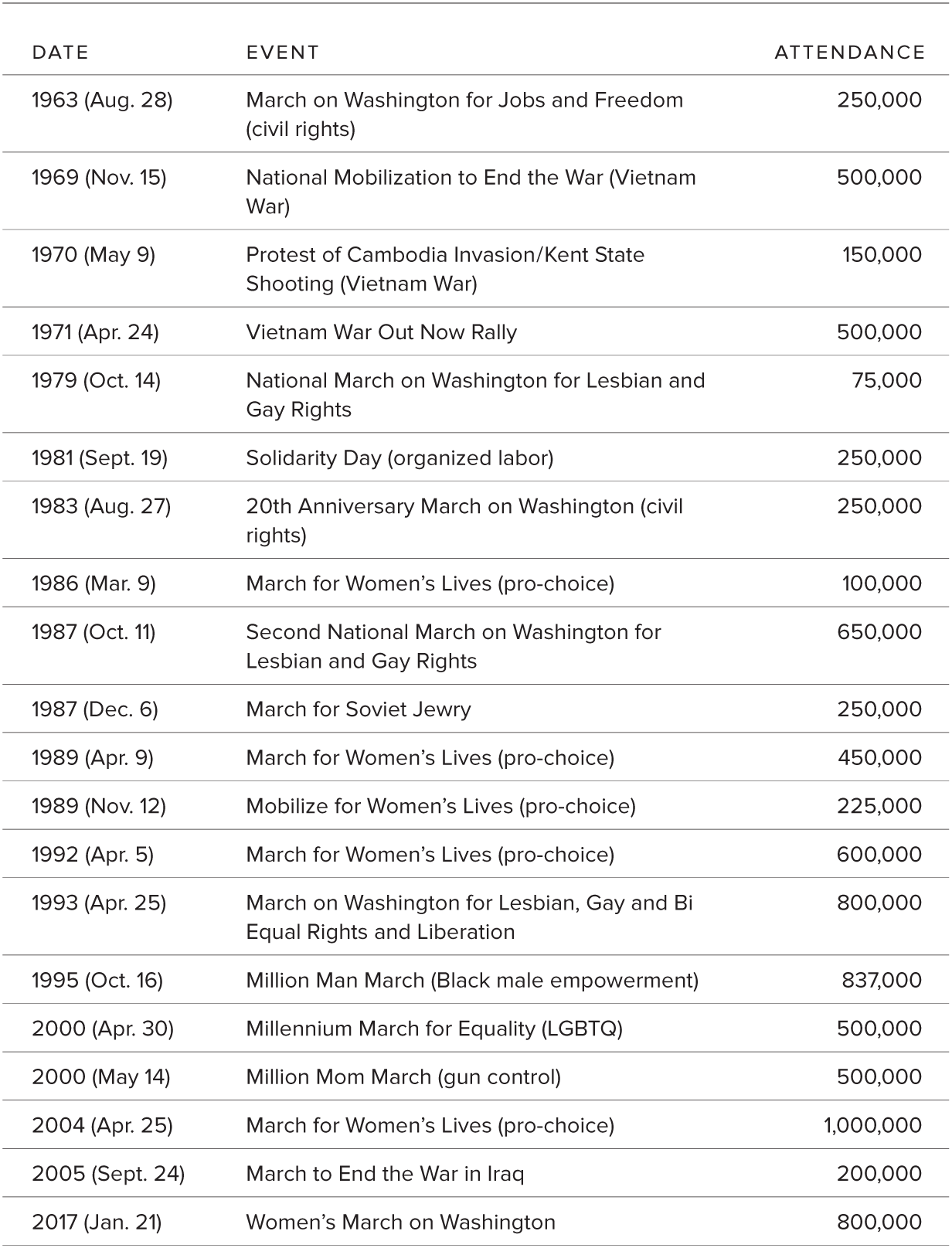

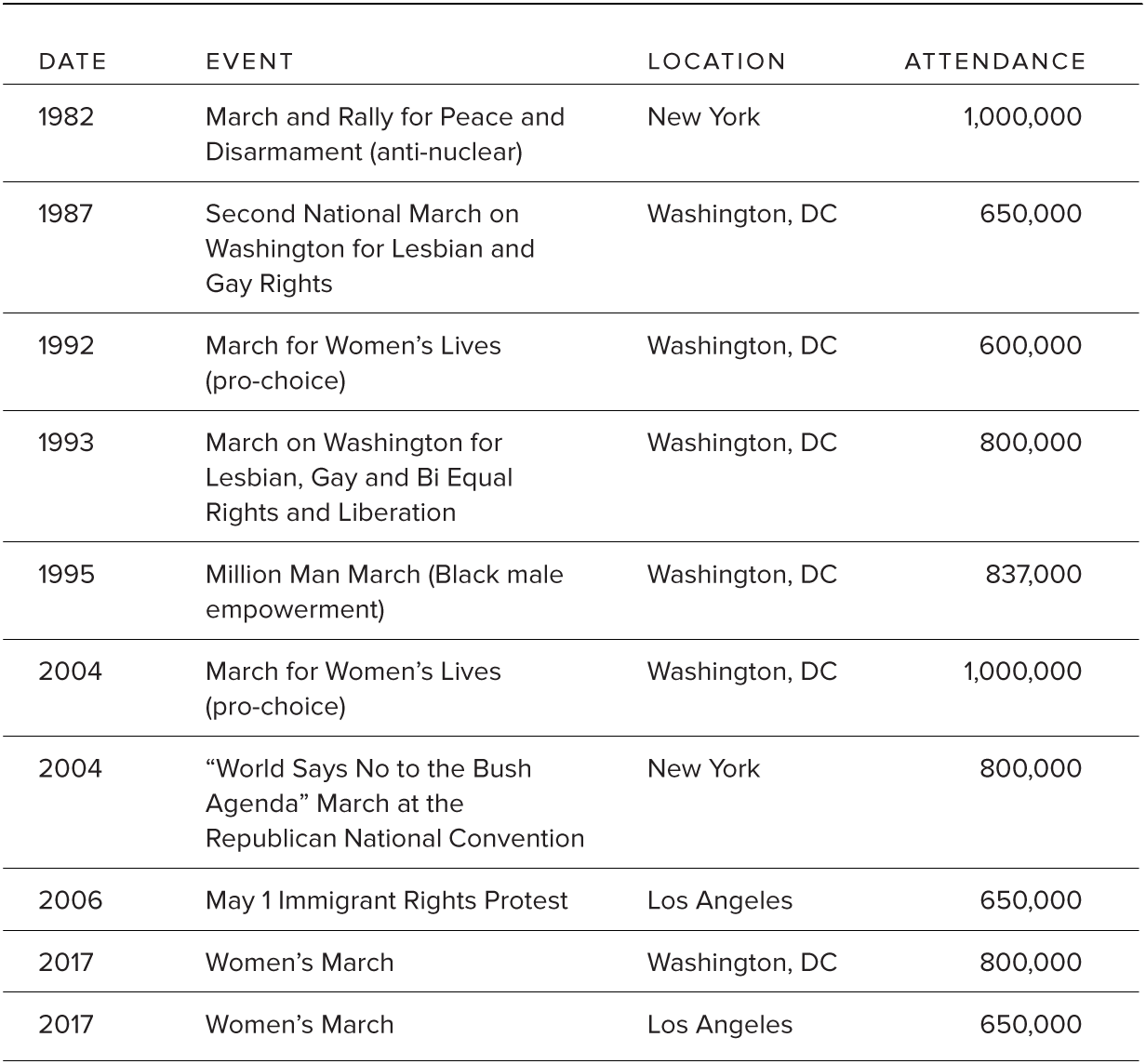

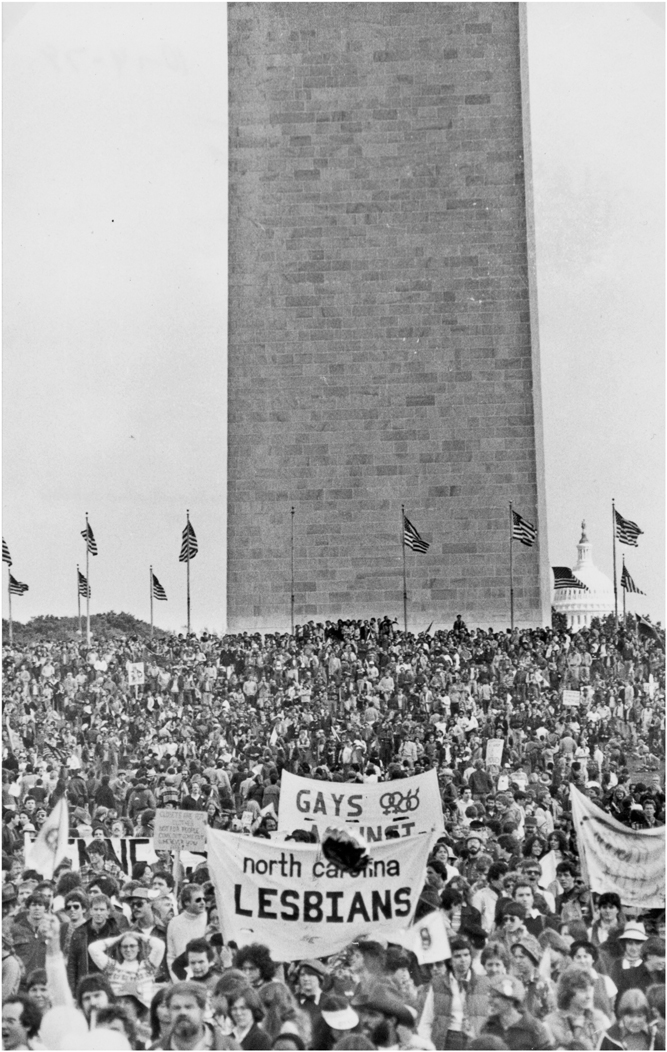

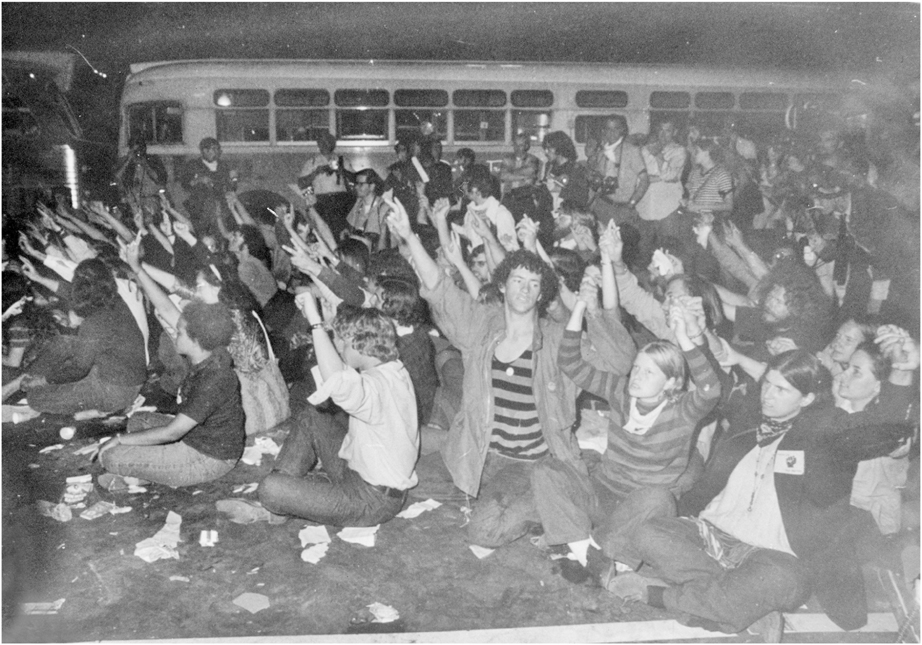

But afterward, you might wonder if that’s all there is. You march, and it feels good to march, but did the marching matter? And if it did, what exact difference did it make? Do protests change policy? Do they change minds? Or do they just let off steam? Millions of Americans have taken to the streets in recent times, breaking previous records for protest participation, but there’s widespread skepticism around demonstrations—a suspicion that protests are purely expressive, a venting of frustration with no quantifiable effect, and that the real work of reform happens through established channels of influence like elections and lobbying. Every time there’s a major wave of protests in the United States, a flurry of think pieces follows, questioning whether demonstrations accomplish anything that can be measured. We celebrate past protests that we think did have lasting impact, from the stately 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom to the unruly 1969 Stonewall riots that kicked off the modern LGBTQ movement, but there’s often a gestural quality to the acclaim, a broad sense that these actions helped create change, but no detailed accounting of exactly how and why.

Some protests, of course, have no more enduring effect than a gust of wind. There are failures as well as successes in any area of human endeavor, and with protests, the odds are against you from the start. By definition, people demonstrate when normal channels are blocked or unresponsive, when institutions allow injustice to flourish, when the powerful act with impunity. Protests are what political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott famously called “weapons of the weak,” used by those who lack the power to achieve their goals through official means. The ultimate measure of a movement’s success may be if it can move from protest to power, from an outside critique to inside influence, but history moves slowly and unevenly. Structures of power are entrenched and resilient, and injustices go deep. The work of movements is filled with setbacks, reversals, and defeats, and victories are often partial or fragile or both. You may need many years of changing attitudes before you can begin to change policy. You may lose for a very long time before you begin to win. If power conceded without demands, protests would never be necessary.

Protests come in many forms, and happen on wildly varying scales, from a single individual kneeling on a football field to a million people marching through the streets of a major city. There are as many kinds of protests as there are tools in a well-stocked toolbox, and part of the difficulty in coming to terms with what protests do is that they don’t all work in the same way. A silent vigil, say, and a freeway blockade are as different in character and effect as a sanding block and a sledgehammer. A vigil is a bid for public sympathy, an appeal to the heart and to common ground. A blockade is intentionally polarizing and controversial; in creating a logistical crisis, it seeks to create a political one, forcing those in power to respond. Successful movements tend to use many different tactics, of which protests are only the most visible, and skilled organizers will use protests of different kinds at different moments in an unfolding campaign.

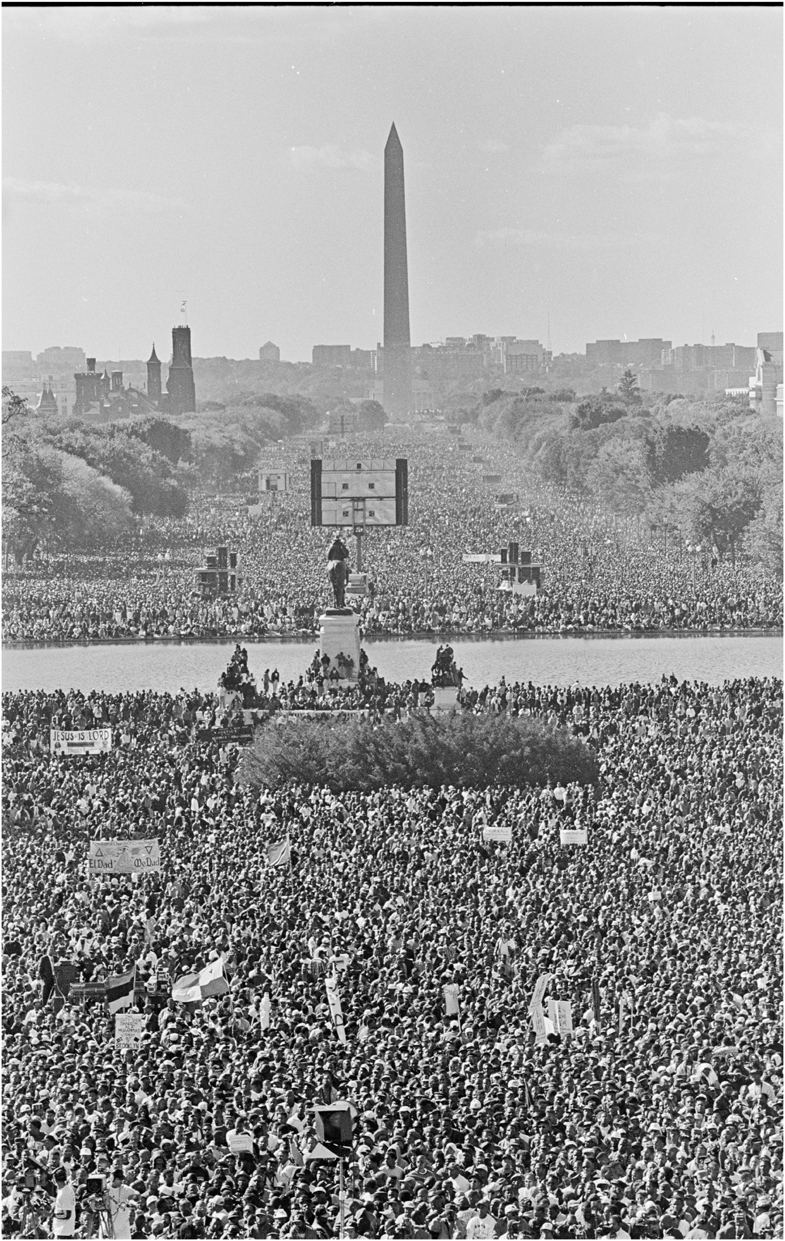

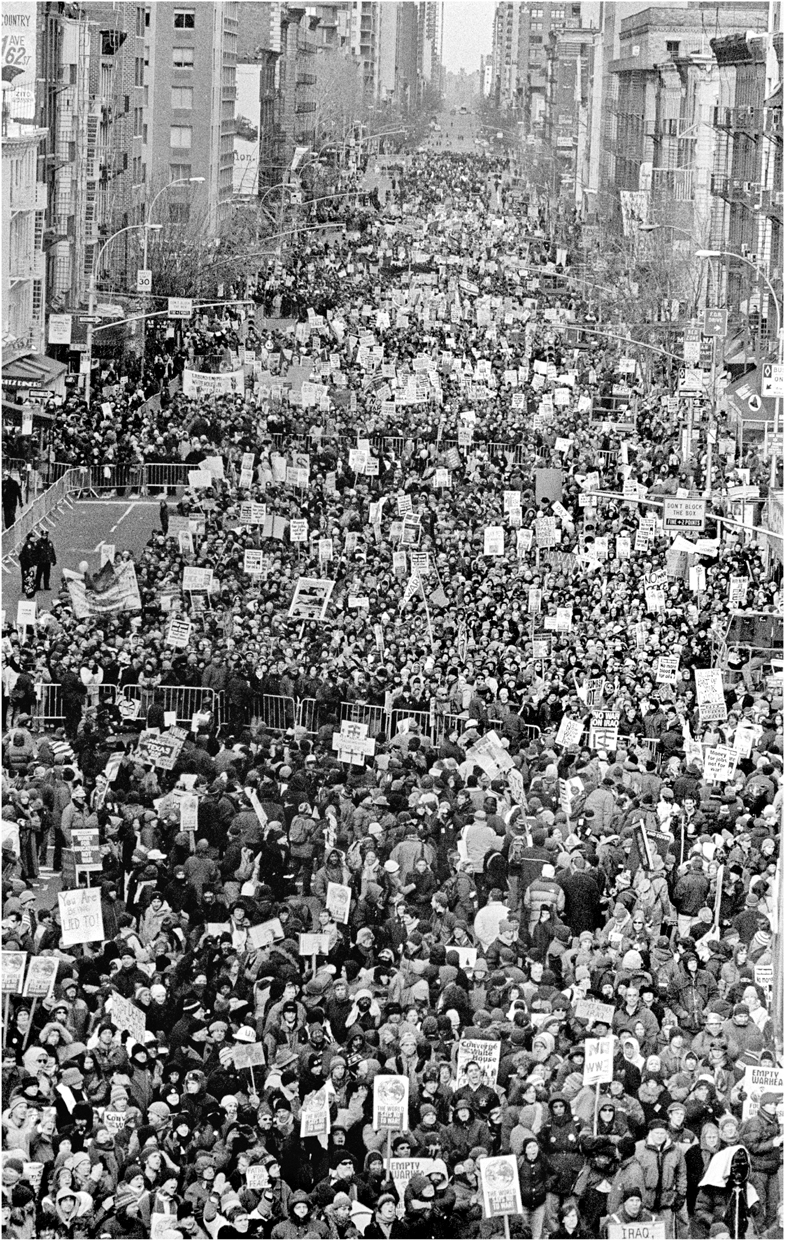

The most iconic form of protest in America is the mass march, exemplified by the legendary 1963 event where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. Mass protests may be the hardest of all to evaluate, even as they’ve become recurring fixtures of American political life. At first glance, they all look similar, with huge crowds converging on the nation’s capital or some other major city to take a public stand. But they are not all alike. Mass protests have been organized very differently over time, and their function has varied and evolved as part of a long series of shifts in the nature of movements and activism in America. Sometimes, a huge demonstration can function like the capstone to a movement, as happened with the 1963 march, which is widely viewed as representing what a successful protest can be. On other occasions, mass protests can channel vast anger with seemingly no effect on the course of events, as happened on the eve of the Iraq War in 2003. In the hope of deterring President George W. Bush from waging a war on false pretenses, millions around the globe poured into the streets for what remains the single largest day of protest in world history; the massive outcry, however, failed to stop the Bush administration’s rush to war. And, in rare and remarkable instances, a mass mobilization can help galvanize and energize a sprawling new movement, as the 2017 Women’s Marches did with the resistance to Trump. These nationwide marches were organized differently from any major protests in American history, and the bottom-up, women-led way they came together gave them a powerful and unprecedented movement-building impact. If you want to understand what protests do and when and how they work, you first have to understand their character: You need to know how to read a protest.

An excellent place to begin is by looking carefully at the signs that demonstrators carry. After all, signs are often the first thing that tells you a protest is a protest and not some other large assemblage of people, like a crowd waiting to enter a performance venue or celebrating the victory of a sports team. People carry signs to communicate, and to affiliate—to tell the broader public how they feel and what they want, and to show they identify with a movement or a group. In most cases, you should be able to figure out at a glance whether a protest concerns the construction of a gas pipeline or the police murder of an unarmed Black teenager or an elected representative’s vote to gut health care. Big protests, especially, almost always feature signs or banners, and these offer rich clues to what’s really going on: how the demonstration came together, what kind of movement it grew out of, who sponsored it, and what impact it might have.

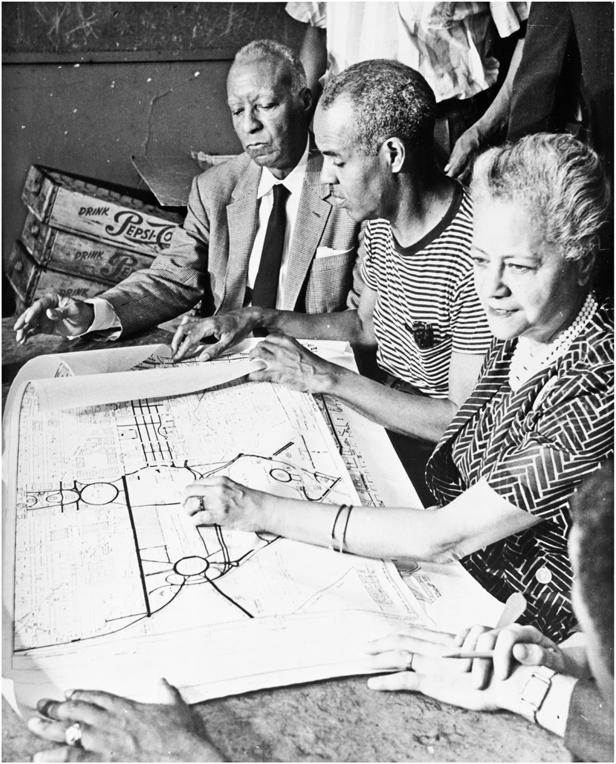

Take a look: Are the signs professionally printed, by and large, and quite similar in appearance? That’s what the posters looked like at the most famous demonstration in US history, the 1963 March on Washington. Examine images from that day and you’ll see impeccably dressed marchers carrying uniform-looking placards, each trumpeting an urgent demand: “WE DEMAND VOTING RIGHTS NOW!” “WE MARCH FOR INTEGRATED SCHOOLS NOW!” “WE MARCH FOR JOBS FOR ALL NOW!”

The 1963 March on Washington is so universally known and so widely celebrated that for many people it’s what comes first to mind when thinking of demonstrations at all. It’s the benchmark against which other large protests are most often measured, so mythic that it almost stands above and outside history in many people’s imaginations—as a pinnacle moment of social struggle, in which the pressing need for change in America’s racial order was conveyed with such force and dignity that reform seemed natural and inevitable. Scholars might debate how much the march can be credited with the passage of the Civil Rights Act the following year—overall, they’re skeptical, seeing it as but one step in a long and complex process—but the connection is firmly cemented in popular understandings of American history. This sense that the march helped secure the passage of key civil rights legislation, along with the enduring resonance of the powerful words that King spoke from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, have led many to view the 1963 March on Washington as the consummate example of what a successful protest can and should be: a convergence that so beautifully crystallizes and amplifies the concerns of those gathered that it pressures recalcitrant institutions to act. By any standard, the event came off splendidly, stirring the world’s conscience, and more than a half century later, it continues to inspire and educate.

But much as the larger history of the civil rights movement has often been distorted and depoliticized in the retelling, so has the nature and impact of this key protest. Of course the 1963 March on Washington contributed to the multifaceted effort to pass federal civil rights legislation in the United States, but the contribution was relatively indirect. It helped create a sense of national consensus around civil rights and gave a new stature and legitimacy to the movement—that is to say, it had a diffuse and long-term influence, the very sort that tends to be either ignored or dismissed as political failure when pundits evaluate other mass protests. Political scientist Jeanne Theoharis has written powerfully about how myths of the civil rights movement have been “weaponized” against subsequent movements, setting up a hallowed standard against which all other efforts have been harshly judged. In popular discourse, a grandeur and effectiveness has been attributed to the 1963 March on Washington that no subsequent march could ever match. In sanctifying this one protest and making it larger than life, all other protests are diminished by comparison.1

The more closely you look at how the march was actually organized, and what impact it had on the unfolding civil rights movement, the more it stands out as singular and anomalous. In a great many respects, from the way the organizing proceeded to the effects that it had, the 1963 March on Washington was unlike any other demonstration that came before or after it. The eye-catching signs that marchers carried on that storied August afternoon are just one small detail in the great drama of the day, but they help explain what made it so unique—and in so doing, help explain how the political landscape for protest, and the parameters for what protests can and do accomplish, have shifted over the decades since. The posters at the 1963 March on Washington look so uniform for a quite extraordinary reason. They were completely controlled by the organizers, who took great care to make sure that the only signs that appeared at the demonstration were ones featuring slogans they had approved. So unusual was this course of action that it would never be repeated at any other sizable demonstration in the United States: The protest march that’s come to epitomize peaceful popular dissent in America was an event where all but authorized messages were silenced.

Volunteers stack signs at the DC office for the 1963 March on Washington in advance of the event.

To understand how and why this happened, it’s crucial to remember that the 1963 March on Washington was the first event of its kind. It was not the first demonstration in the nation’s capital, but it was the first genuinely mass one, and the first protest march of its size in US history. The man who would direct the organizing, longtime civil rights and labor leader A. Philip Randolph, had dreamed for decades of holding a massive march on Washington, but none had ever actually happened. There had been a few noteworthy prior events in DC that were designed to showcase collective strength, but they were modest in scale and almost always parade-like in character. Five thousand women marched along Pennsylvania Avenue, for instance, for an elaborate 1913 Suffrage Procession and Pageant. A little more than a decade later, the Ku Klux Klan, then just past the peak of its popularity, brought 50,000 of its members to parade through Washington in full hooded regalia in 1925 and 1926. Some 17,000 World War I veterans came to demand their bonus pay in 1932, in the one sizable pre-1963 DC protest that wasn’t organized in parade fashion; the Bonus Army’s ragged occupation ended in bloodshed after President Hoover ordered the police to evict them. A. Philip Randolph had announced a major march in 1941 to protest racial segregation in the armed forces, an all-Black mobilization that he vowed would top 100,000 attendees, but he called it off at the last minute after then-President Roosevelt met the protest’s central demand and signed an executive order prohibiting racial discrimination in federal training programs and defense industries. Until the 1963 event that we’ve come to think of as the basic template for big national protests, there was, in fact, just one mass protest march of any kind in America, a beautifully organized civil rights demonstration by more than 125,000 people in Detroit that took place in late June 1963, when work on the March on Washington was just getting under way. The success of this little-remembered event, the Detroit Walk to Freedom, helped spur and solidify plans for the DC march.2

Women’s Suffrage Parade proceeds down Pennsylvania Avenue, 1913.

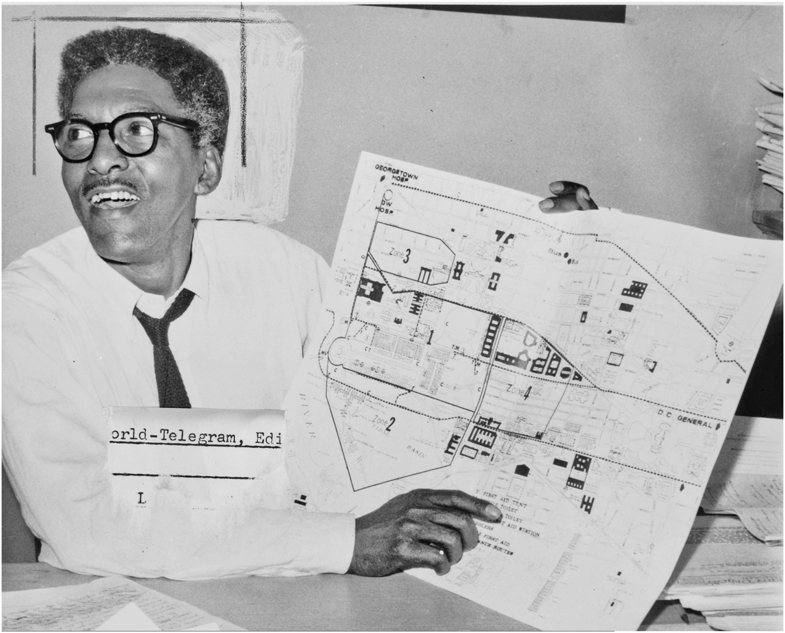

So the planning for the 1963 March on Washington has to be understood as brand-new and unprecedented, a bold and audacious experiment with a type of collective action that hadn’t been tried in the United States before. “Mobilization” is first and foremost a military term—the readying and amassing of troops for war—and before that August Wednesday, no civilian force in the United States had ever tried to move people on this scale for political purposes. There had been very large parades of various kinds, from ticker tape parades celebrating distinguished foreign visitors or victorious sports teams to the famous Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, which dates back to the 1920s, but the huge crowds who attended these events came as spectators, not as marchers. To a substantial degree, organizing the March on Washington was a matter of improvisation and guesswork, as there were no prior models to follow for organizing a protest this large. And although the staff and coalition for the event included significant white participation, it’s worth stressing that the mass protest march in America was fundamentally a Black invention: conceived of by Black leaders, shaped by Black organizing traditions, and mostly built through Black organizations and networks. Preliminary political discussions about the march began many months ahead of time, but the logistics for this enormous undertaking were largely thrown together in a dizzying eight weeks. Randolph was the official director, but his deputy, the legendary organizer Bayard Rustin, whose homosexuality and past ties to the Communist Party made him too controversial to serve as the acknowledged leader, served as the hands-on coordinator for the endeavor.

Members of the Ku Klux Klan parade on Pennsylvania Avenue, ca. 1926.

Six civil rights organizations, of varying strength and character, came together to cosponsor the march. Their leaders, the so-called Big Six, constituted the decision-making body for the march, which was later expanded to include the heads of the United Auto Workers and major Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish organizations, who together were called the Big Ten. A somewhat larger administrative committee was tasked with implementation. All six groups donated staff members and other resources to the effort, and to different degrees leveraged their mailing lists and networks of local contacts to recruit participants. Randolph’s organization, the little-known Negro American Labor Council (NALC), kicked off the initial work. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), two groups that favored bold direct action and innovative local organizing to challenge racial segregation, came on board early, but both groups’ enthusiasm for the march waned as the planning proceeded and its character grew ever milder and more orchestrated. Some local CORE chapters were quite active in publicizing the march and mobilizing people to come, but others openly criticized the event as too tame and compromised. Dr. King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), brought moral authority and of course the charismatic and inspiring figure of King himself, as well as a network of clergy whom organizers hoped would mobilize their flocks—the march was scheduled for a Wednesday specifically so pastors would be free to bring their congregations. The SCLC, though, did not typically have strong local infrastructure—within the wider civil rights movement, King and his organization were often faulted for parachuting into sites of local conflict only to depart when the spotlight waned—and it was so financially and organizationally strapped that it contributed little money or mobilizing might to the effort. The august National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had the biggest membership and strongest network of local chapters of all the groups that came together for the march, and its infrastructure proved crucial to bringing the huge crowds to Washington. The NAACP’s long-standing preference for legal and legislative work and caution around street protests, however, meant that it would participate only if Randolph and Rustin agreed to scrap any plans for civil disobedience and soften any radical edge to the event, which in turn blunted the enthusiasm of SNCC and CORE. The final member of the coalition, the National Urban League, had almost no experience with demonstrations, but it had other resources to contribute, from staff members to office space.3

Bonus Army marchers from Oregon en route to Washington, DC, to demand their pay, 1932.

Bringing these six disparate groups together to organize an event on such a grand scale required many compromises; working with the authorities in Washington, DC, entailed many more. To a degree that would never be repeated in subsequent mass national demonstrations, the planning developed in uneasy but close collaboration with one of the movement’s major targets: the administration of President John F. Kennedy, whose actions in defense of the basic rights of African Americans had been limited and tepid. The shocking events in Birmingham that May, where police led by sheriff Eugene “Bull” Connor had infamously attacked civil rights protesters, including children, with police dogs and fire hoses, had finally pushed the president to introduce civil rights legislation in Congress. But that didn’t mean Kennedy welcomed having crowds of protesters march on Washington to make sure it became law. Indeed, Kennedy did everything in his power to try to dissuade the organizers from holding the march, arguing that it would be counterproductive. “The Negroes are already in the streets,” Randolph had defiantly countered at a June 22 White House meeting between civil rights leaders and the president. “There will be a march.” For the administration, the question quickly became how to contain it, and Kennedy reportedly declared in private, “Well, if we can’t stop it, we’ll run the damn thing.” That was a gross exaggeration of what happened, if indeed Kennedy said it at all, but there was in fact thoroughgoing coordination between protest planners and the White House on nearly every aspect of the day, going well beyond the kind of logistical support that would become standard administrative practice for protests in the future. Inevitably, this cooperation came with many subtle and not-so-subtle moves to control and limit the march, all justified on the grounds of ensuring that the event would not descend into chaos.4

Civil rights leaders visit the White House to discuss march plans, June 22, 1963. Martin Luther King Jr. and Roy Wilkins of the NAACP are flanking Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy; lead march organizer A. Philip Randolph is barely visible at the far right.

Kennedy set the tone in July, with a statement of public support for the march that spent far more time sternly lecturing those who planned to join the event than it did affirming their aims. Despite citing “every evidence that it’s going to be peaceful,” Kennedy declared, “I have warned about demonstrations which could lead to riots, demonstrations which could lead to bloodshed, and I warn now again about them.” He continued, “I would suggest that we exercise great care in protesting so it doesn’t become riots.” Of course, nearly all the violence associated with the civil rights movement as of 1963 was white violence directed toward it, and Kennedy knew that; there was a cynicism to his finger-wagging tone. As Bayard Rustin and a young march staffer, Tom Kahn, put it in a private memo to Randolph a week before the march, “It is not our people who invented lynching, who have set vicious dogs loose in the streets, who have turned high-power hoses on defenseless women and children. We have not burned buses or led insurrections against federal marshals.” Nor, of course, had civil rights activists murdered their opponents, while the cold-blooded killing of NAACP official Medgar Evers on June 12 of that summer foreshadowed many assassinations to come. But the threat to marchers was not the Kennedy administration’s chief concern. Indeed, just a week before Kennedy made his cautionary remarks, an official from his Justice Department had flatly refused in a meeting with Rustin and other organizers to take any action whatsoever to protect those coming to Washington from possible attacks. (“We have no legal authority to police the channels of commerce or to take any preventative action,” the official blandly declared.) Lacking any guarantee that marchers would be protected from white violence—some were in fact viciously assaulted on their way home—while having to respond constantly to white fears, Rustin and Kahn’s memo to Randolph concluded, “The question of violence seems to have exercised a fascination far out of proportion to what it deserves. There is no doubt but that for some people the source of this fascination is a conception that any large gathering of Negroes represents a threat of violence.”5

That conception shaped news report after news report in the lead-up to the march, helping create an atmosphere of apprehension and anxiety. “There are a great many people, as I am sure you know, who believe that it would be impossible to bring more than 100,000 militant Negroes into Washington without incidents and possibly rioting,” the host of “Meet the Press” intoned portentously in an interview with NAACP executive secretary Roy Wilkins a few days beforehand. The Los Angeles Times echoed this concern: “The specter of riot hangs over the march. Some 200,000 angry people in one place on a hot day in August makes for a combustible situation.” This drumbeat of dire warnings was so loud and insistent that it almost seemed like some of the people issuing them hoped that things would go awry. Indeed, one Dixiecrat from Louisiana, Senator Russell B. Long, confessed, “I would just as soon the whole thing broke out in riots, though I am not advocating this. I suppose the whole South would just as soon it got out of hand.” As Life magazine editorialized the week before the march, “It boils down to a feeling that the Negro is ‘going too far.’ In a recent Gallup poll six out of 10 whites felt that Negroes are hurting their own cause with undue militancy.”6

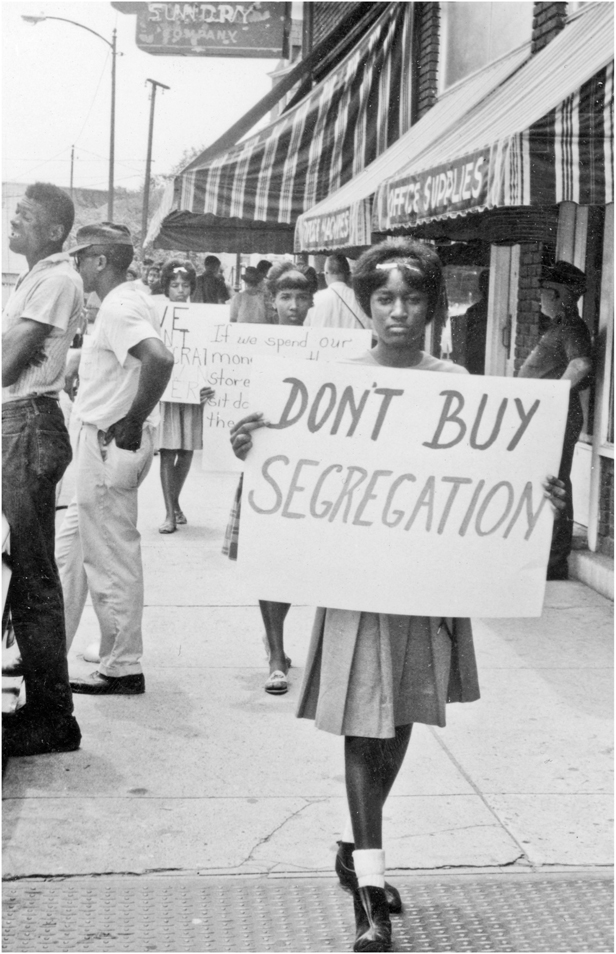

Protesters form a moving picket line outside segregated Southside Sundry in Farmville, Virginia, July 1963.

Protesters block the road leading to Jones Beach, New York, in a protest against hiring discrimination, July 1963.

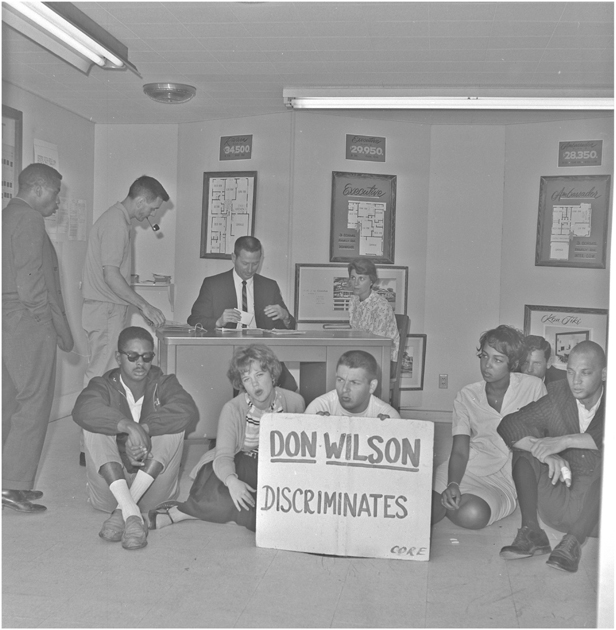

The planning for the march was taking place, it must be said, against the backdrop of a powerful surge of local organizing, and conflict, around civil rights. Though it’s not much remembered except among scholars, the summer of 1963 witnessed an extraordinary number of local civil rights protests all around the country: more than 1,100, in some 220 cities, spread throughout every region of the United States. The struggle in Birmingham had the highest profile, but it was only one of a great many flash points all around the country, from Denver to Philadelphia to Tallahassee. In community after community, local people were using direct action, including pickets, sit-ins, and marches, to confront segregation and discrimination right where it was happening, directly placing their bodies in the way of injustice. Demonstrations took place all summer long not only at segregated lunch counters and restaurants, but also at schools, housing developments, job sites, and places of recreation such as movie theaters and swimming pools. Hundreds were arrested after protesting outside a segregated Holiday Inn in Savannah, Georgia, and outside a whites-only amusement park in Gwynn Oak, Maryland. In Long Island, protesters blocked roads leading to Jones Beach to challenge discriminatory hiring practices there; in Southern California, they occupied the sales office of a housing development to combat bias; in St. Louis, they blocked school buses that were taking children to segregated schools. Then as now, these kinds of targeted and very direct actions were often successful at pressuring individual businesses or institutions to change, and the threat of facing such protests led numerous others to follow suit. As the Kiplinger Washington Letter put it in its weekly update to business leaders in late July, “Southern businessmen are reacting to the pressure in this way: Many are going along reluctantly with removal of symbols of prejudice . . . desegregating rest rooms, water fountains, lunch counters, restaurants. Hotel men say: ‘Where it has been done quietly, desegregation has made little disturbance. But if we wait for trouble, sit-ins, etc. it usually means economic loss. We hope to avoid demonstrations.’” But for all the effectiveness of these local protests, they were small-scale and piecemeal by definition; the victories were tiny in comparison to the pervasiveness of discrimination. Each local advance pointed the way toward the sweeping, national policy changes that would be needed to uproot segregation, but also underscored that local action alone was insufficient.7

Members of CORE hold a sit-in at Southwood Homes Sales Office in Torrance, California, June 1963.

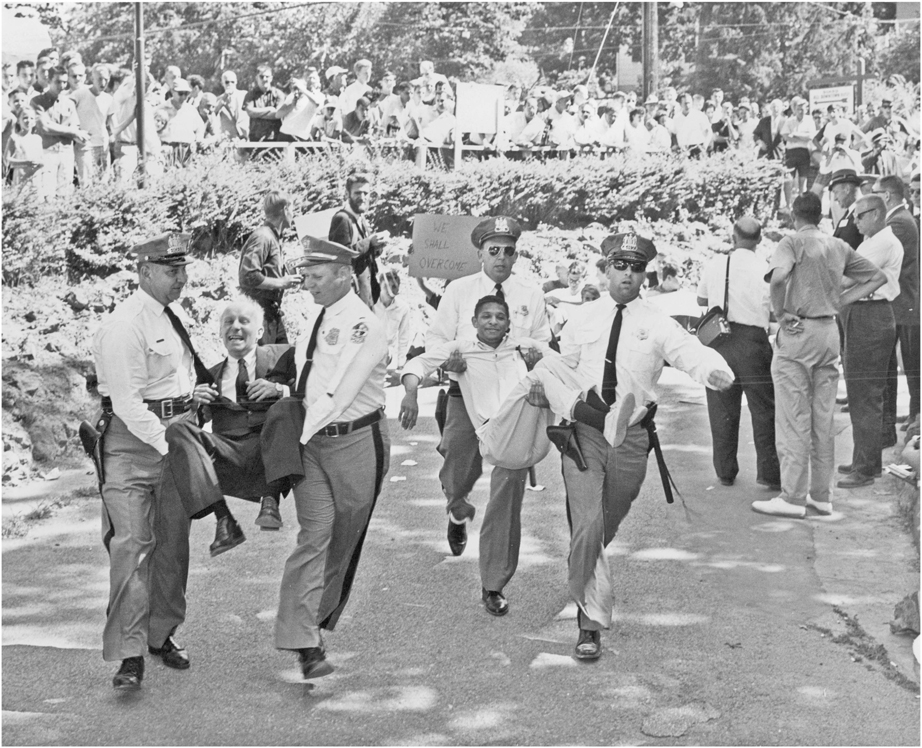

Backlash, meanwhile, was also growing, as was frustration with the slow pace of reform. At numerous local protests, demonstrators encountered violent responses from police or hostile white crowds or both, as for instance in Lexington, North Carolina, where a thousand white people rioted after fifteen Black protesters tried to integrate a local bowling alley and other businesses. White racists instigated most of the clashes, but in some cases, including in Birmingham, protesters fought back by throwing bottles or rocks. As protests flared up all around the country that summer, there was an unmistakable sense that many Black communities were becoming thoroughly fed up with ongoing white intransigence. There were signs of a new militancy emerging at the grassroots in some locales, and the early stirrings of what would become Black Power. A few protests did become direct clashes, including in Cambridge, Maryland, an Eastern Shore community where local activists had been trying for some time to desegregate local restaurants and recreational facilities. The movement there, led by the poised and uncompromising Gloria Richardson, was one of the first to question strict nonviolence and embrace notions of radical self-defense, including armed self-defense. Several protests in June became so violent that martial law was declared and the National Guard brought in, developments that were in the forefront of President Kennedy’s mind when he issued his cautions about the March on Washington. Though local chapters of the major national groups were involved in many of these community-level struggles, this wave of local protest spilled well beyond the preexisting organizational bounds of the civil rights movement. As scholar Thomas Gentile noted, many local protests “were relatively spontaneous outbursts of activism by individuals and small groups, most of whose past involvement in demonstrations were minimal. . . . There was often no single sponsor like CORE, SNCC, the NAACP or SCLC.”8

Police remove protesters from a sit-in at segregated Gwynn Oak Amusement Park, Maryland, July 1963. Photo by Walter McCardell

The climate of fear surrounding the upcoming march, the desire to contain the restless energy from the grassroots, and pressure from the Kennedy administration shaped a great many decisions about the planning. Initially, the convergence was to take place on multiple days and involve a range of tactics, including civil disobedience and citizen lobbying; Rustin in particular hoped that militant nonviolence would give the entire gathering a strong and uncompromising tone. To secure the NAACP’s involvement, those ideas were quickly scuttled in favor of a fully legal one-day march and rally. Plans to march to the Capitol were soon deemed too confrontational—the Capitol Grounds Act of 1882 made all such actions illegal, until it was struck down by a court in 1972. And Kennedy administration officials made it clear they didn’t want the march going anywhere near the White House, either. So the route was shifted to take marchers from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial, two photogenic and symbolically rich locations that were, however, distant from any actual seat of power in DC. Many smaller logistical decisions also flowed from the climate of caution: Until fairly late in the process, organizers discouraged people from coming to the march in private automobiles, feeling they could manage the crowds better if everyone arrived on buses and other organized mass transit. They told marchers to leave children at home, and instructed them to depart the District by sundown. DC authorities decided to close all liquor stores for the day, a rather insulting move, while President Kennedy placed thousands of troops on standby in case trouble erupted.

March on Washington organizer Bayard Rustin holds a map showing plans to accommodate the expected crowds.

A sit-in blocks a downtown St. Louis street in a protest against school segregation, June 1963.

The fear also influenced how organizers decided to handle the protest signs, which represented the public face that protesters would show the world. Randolph and Rustin wanted to be sure that the event not only would be peaceful and orderly, but that it would look that way, too. At the same planning meeting with police officials where the Justice Department said it couldn’t do anything to protect those coming to the event, a deputy DC police chief asked the organizers if marchers would be carrying “placards that will help inflame the opposition.” Rustin had a ready reply. “The staff is proposing . . . that all placards used be made by the central committee and that no people coming in will be able to carry their placards,” he explained to police. The idea presumably came from Randolph, who had intended to control all signs and slogans for the big 1941 march that was called off after it achieved its aims. The signs that marchers would carry for the 1963 event, Rustin reassured police officials, would be “designed for the maintenance of order.”9

That was indeed how the National Committee decided to handle the signs. The first organizing manual for the march, an eight-page guide that was mailed out to local groups and organizers just a week after the police meeting, gave unambiguous instructions, underlined to emphasize their importance: “All placards to be used on the March will be provided by the National Office. No other slogans will be permitted.” The organizers never publicly explained the thinking behind this decision, but the rationale clearly extended past projecting an orderly image to larger questions of political control. “The reasons for this policy should be obvious,” read a passage drafted for the second organizing manual, but then cut before it went to the printer. “It would not be fair to the more than 100,000 marchers we expect if some people carried slogans which went beyond the program that formed the basis of recruitment to the March. If each of us pressed for his own program, the total impact of the March would be diffused and weakened.” This was a vision of unity as unanimity, and a rather audacious level of political discipline to seek to impose on the wide array of forces that were being mobilized to attend the march. It was also a departure from standard civil rights movement practice: Organizations with printing budgets like the NAACP and CORE routinely created signs for protests, but participants could make and bring their own if they wished. Many local actions didn’t even include signs; the presence of bodies—especially Black bodies—where they were not supposed to be, whether that was sitting at a lunch counter or blocking a street, was signifier enough. Where civil rights demonstrators did carry posters at local protests, they were generally handmade; the invention of the Magic Marker in the mid-1950s had made sign making a quick, easy, and affordable matter. Images from the big Detroit Walk to Freedom earlier that summer show a vibrant mix of official and homemade placards, with plenty of the latter. If fear of unruliness and disorder was the backdrop for the decision to control the signs at the 1963 March on Washington, an expansive and rather commanding vision of leadership was required to implement it.10

The Detroit Walk to Freedom, the first mass protest march in American history, held two months before the 1963 March on Washington.

As the planning proceeded, there was pushback from local organizers about this limitation; some groups quite understandably wanted to carry their own signs and devise their own slogans. After some debate, the leadership had to loosen up a little on their control over the placards. The National Committee still directed which slogans would be allowed—staff members and interested collaborators like famed labor leader Moe Foner drafted long lists for them to consider—but some groups were allowed to make and bring their own signs so long as they limited themselves to the authorized messages. Certain categories of preapproved organizations—religious groups, labor unions, fraternal organizations, and of course the sponsoring civil rights groups—were also allowed to bring “signs of identification,” advertising their participation in the event. But, they were admonished, “such identification should carry only the name of the organization; no slogans are permitted.” And no one else was supposed to carry any poster or placard that was not provided by organizers. This policy was emphatically not a mere request. The marshals for the march—a force of some two thousand off-duty Black police officers, firefighters, and prison guards—were tasked, among other things, with “policing picket signs,” as the NAACP’s full-time staff person for the march, John Morsell, phrased it. Anyone carrying an unauthorized sign was to be handled under the standard protocol for disrupters: “Detect, point out, and encircle offenders, using at all times nonviolent persuasion to control the situation.”11

Volunteers prepare thousands of signs for the 1963 March on Washington.

Black nationalist leader Malcolm X, whose political differences with the march organizers were far-reaching, characterized the handling of the signs as one of numerous reasons why he decided to boycott the march. Plenty of people in direct-action-oriented groups like SNCC and CORE were angered by the decision to scrap the initial plans for civil disobedience and only reluctantly went along with a plan of action they found tame. Malcolm X went much further, emphatically refusing to participate in an event that allowed so little political autonomy. “There wasn’t a single logistics aspect uncontrolled,” he explained in his 1964 autobiography. “The marchers had been instructed to bring no signs—signs were provided. . . . They had been told how to arrive, when, where to arrive, where to assemble, when to start marching, the route to march.”12

He had a point. The sea of uniform signs at the March on Washington reflected a certain key quality to the march organizing: a directive leadership style that in many respects stood at odds, quite deliberately, with the impatient and restive grassroots. You didn’t have to belong to the Nation of Islam to find this level of control off-putting. It was out of step with the broad direction not just of the grassroots civil rights movement, but of many parts of the left, especially the nascent New Left. New ideas were in the air about what leadership should look like and how groups should be structured, and the movements with the most new energy and momentum, from SNCC to Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which had been founded the previous year, were experimenting with organizing methods, group structures, and forms of decision making that were decentralized, inclusive, and participatory.

The differences in organizing styles can’t be reduced to any single factor, but some were matters of political and ideological habit. Attempts by segregationists like Alabama governor George Wallace to paint the main march organizers as Communists failed miserably, because they simply weren’t true. It was well known that Rustin had once been a Communist Party member, but he had left because of political differences way back in 1941; none of the other key organizers were members, and indeed quite a few were vehemently anti-Communist. Many key march planners were, however, socialists, and a number of them belonged to a small party-style group of the anti-Communist left, the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL), that featured a centralized organizational structure, top-down leadership, and a penchant for asserting political control through backroom machinations. March staffers Rachelle Horowitz and Tom Kahn were key leaders of YPSL, which had tried, and failed, to take over SDS early on in order to steer its politics in a more traditionally Old Left direction. Others who were centrally involved in the march organizing, such as administrative committee chair Cleveland Robinson, came from parts of the labor movement where hierarchical structures and centralized decision making were standard and unquestioned organizational traits. If there was a whiff of Leninism in the repeated emphasis on “discipline” and “order” in the planning meetings and organizational materials, it surely flowed from these Old Left affiliations. Rigid control of political behavior—and messaging—was a long-standing practice in these precincts of the left.13

Gender also played a notable part. Within the grassroots civil rights movement, Black women like Ella Baker of SNCC and Septima Clark of the SCLC were at the forefront of pioneering empowering new approaches in their organizing work, but neither they nor any other women had a voice in the top march leadership. Indeed, women weren’t just sidelined from any decision making or other prominent role in the March on Washington; the decisions to exclude them were made in the most peremptory way possible, as if the matter hardly warranted serious consideration. Early in the march planning, Anna Arnold Hedgeman, a longtime civil rights organizer who was part of the National Council of Churches’ Commission on Religion and Race and the only woman on either of the march leadership bodies (she was appointed to the larger, less powerful administrative committee), urged Randolph to expand that committee to involve key Black women’s organizations, including the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs and the National Council of Negro Women. These organizations had vast reach. In 1963, the NCNW alone had a larger membership than that of the NAACP, which had been allowed to veto plans for civil disobedience because its organizational resources and half-million members were viewed as crucial to the march’s success. The women who made up the active base of these clubs and local organizations had long played highly consequential grassroots roles in the civil rights movement. Hedgeman hadn’t even requested that these groups be included in the powerful National Committee, though it makes for an interesting thought experiment to imagine what might have happened if they had been; she was requesting only that they have a central and recognized role in implementing those leaders’ decisions. “As usual, the men must have discussed the matter in my absence,” she later recalled. The proposal was rejected out of hand, without even informing her.14

Organizers A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, and Anna Arnold Hedgeman of the National Council of Churches, the only woman with any official role in the 1963 march planning.

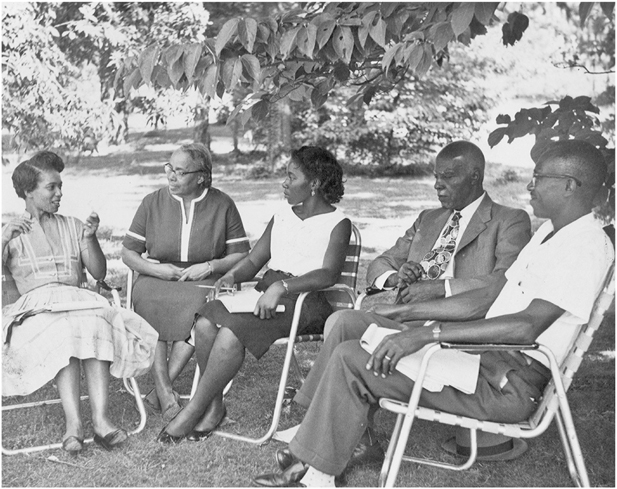

Septima Clark (second from left) meets with a group of students at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, 1958.

The divergent organizing visions were captured in a story recounted by Septima Clark, whose citizenship schools in the Deep South were providing an important model for grassroots empowerment. “I sent a letter to Dr. King asking him not to lead all the marches himself but instead to develop leaders who could lead their own marches,” she explained. “Dr. King read that letter before the staff. It just tickled them; they just laughed.” Attempts to have a woman included among the march speakers were no more successful than Hedgeman’s effort to bring more women into the administrative committee. Appeals to the leadership continued right up to the morning of the march, to no effect. John Morsell, the NAACP representative on the administrative committee, described the effort in terms that reflect how disdainfully the leadership viewed these appeals: “We became aware that there was some resentment on the distaff side, because it was all men and Anna Hedgeman who is a great feminist was all swollen up because there was no woman.” It was a total shutout. Recalled Dorothy Height, president of the National Council of Negro Women at the time, “Nothing that the women said or did broke the impasse blocking their participation. I’ve never seen a more immovable force.”15

If a certain directive masculinity shaped the march organizing, it’s important to underscore that it was a Black masculinity, and that gave it a different significance both within the movement and within American society at large. A. Philip Randolph had long embraced a vision of civil rights centered on the notion of “manhood rights,” uplifting the status and dignity of Black men as a central part of the struggle for racial justice; the distinct problems facing Black women went mostly unmentioned. Rustin, King, and many other civil rights leaders shared elements of that view, and it shaped the movement’s overall discourse and demands. The second most famous set of printed protest signs in American history, after the ones at the March on Washington, may be the “I AM A MAN” signs carried by striking sanitation workers in Memphis in 1968—the simple fact of asserting Black men’s humanity and masculinity was a profound challenge to the existing racial order. That made sexism within the civil rights movement a more delicate and complex matter than the sexism of, say, the white left during this period. For the time being, Black women in the movement mostly kept their frustrations with male leadership out of public view. They knew what the men would not acknowledge through formal power sharing: The movement’s backbone was women. As Coretta Scott King put it in 1966, “Women have been the ones who have made it possible for the movement to be a mass movement.”16

Administrative and clerical staff at the March on Washington office in Harlem, summer 1963. Photo by Werner Wolff

Women were sidelined from any official role in the march or its leadership, but the evidence suggests that they carried out a great deal of the actual work of getting huge numbers of people to come to DC. It took an enormous amount of coordination to reach out to potential supporters on a mass scale, persuade them to join the march, and get them safely to and from the event. Some of the mobilizing took place through exhortation, as King and other leaders took to the media, or to their pulpits, to encourage participation. High-profile entertainers like Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier also helped spread the word. But a great deal of the outreach came through much more direct, face-to-face means, like street leafleting, and through formal and informal networks like clubs and social groups; national protests rely on local organizing. Black women had long been instrumental in anchoring this kind of grassroots work within the civil rights movement—to an important extent, mobilizing was informally defined as women’s work, going back at least to Montgomery in 1955, when women launched the famous bus boycott by secretly hand-distributing some fifty thousand leaflets to nearly every Black home in the city within twenty-four hours of Rosa Parks’s arrest. (Male leaders, including Dr. King, stepped in and took over formal leadership of the boycott the next day, without even including the women in the meeting where they assumed control.) In much of the civil rights movement, as in many other movements to come, “Men led, but women organized,” to quote historian Charles Payne’s pithy summary. Women’s energies and expertise were instrumental in spurring large numbers to attend the March on Washington, even as women were denied any official recognition or decision-making power.17

Rustin’s long experience as a protest organizer gave him a deep understanding of how delicate it could be to try to steer a movement as completely as the march leadership was seeking to do, and in one staff meeting he even joked about the imperiousness of the decision-making process. Rachelle Horowitz, the march’s transportation coordinator, recalled a “hilarious” staff discussion of how the leaders wanted to handle everything from the signs to the food that marchers should bring. “The staff at that point was all involved with all the more intricate questions that were then going to be presented to the administrative committee and the Big Ten—they included where we were going to march—how much they will speak,” Horowitz recalled in 1967. “At one point during the discussion the question of lunch [came] up and Bayard announces they are going to put in the manual that people should bring peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and I looked up and innocently said, ‘Peanut butter and jelly?’ and he said, ‘Don’t argue about this, when the Big Ten have decided.’”18

It was no joke, though: The lines of authority were clear. The Big Ten were to lead—and the marchers were to follow. They were to speak—and the crowd was to listen. Few remember this fact, but all ten men delivered speeches that day, with King’s legendary address coming so late in a long day that the crowd was weary and many marchers had already begun to depart. Though funds for the march were tight, Rustin had made a special point of ordering a very expensive top-of-the-line sound system to ensure the crowd remained an audience. “Once you get that many people they are, essentially no matter what other factors are involved, a mob, unless they can hear,” Rustin explained in an interview four years after the event, an assertion that would of course be disproved at dozens of mass protests to come. Passivity was built into the March on Washington planning: Participants were mobilized as bodies, but not as voices. This quality even extended to the way the musical entertainment was handled. In a striking departure from the usual movement practice of joining together in singing freedom songs as a crucial expression of collective engagement and solidarity, none of the performers at the Lincoln Memorial invited the crowd to join in.19

Not everyone who attended the huge and historic event was willing to give up their autonomy so readily. Plenty of people, of course, sang without invitation, at many points throughout the day. A small number of marchers defied the leadership’s instructions and brought their own signs—most notably, representatives of some of the intense local struggles that had unfolded earlier in the summer and others who wished to bear witness to the incredible violence and suffering that local movements had experienced. A group from Americus, Georgia, where dozens had been beaten and arrested at protests outside a segregated movie theater in July, carried a sign that detailed some of the injuries they had sustained: “Milton Wilkerson—20 stitches. Emanuel McClendon—3 stitches (Age 67). James Williams—broken leg.” Eighteen-year-old James Lee Pruitt, who had been jailed for fifty-two days earlier that summer for taking part in a local voting rights protest in Greenwood, Mississippi, also brought a handmade sign. Its message could hardly be characterized as inflammatory: “We Must Have the Vote in Mississippi by 1964,” it read. But Pruitt’s slogan, however heartfelt and noncontroversial, was not included among the authorized ones, so marshals for the march followed protocol, surrounding him and taking him into a tent for questioning. Only after they had detained him for a time was he able to persuade them to let him keep his sign and participate in the march.20

Dr. King’s resounding speech is of course the most famous element of the March on Washington. Accounts of the day typically feature images from the rally, where King spoke and the audience listened, and not the march, the part of the day’s program where the crowd participated most actively. But there is one oft-recounted moment from the march, and it reveals much about the event’s underlying character. The march was only supposed to step off once the ten leaders were arrayed in a big line at the front for the news cameras. (Coretta Scott King and other wives of the leaders were not allowed to march with them; they marched separately, over on Independence Avenue.) The crowd was restless, though, and in no mood to wait, and people began marching before the men had lined up to lead them. The marshals had to scramble to open up sufficient space in the moving mass of bodies for the leaders to take their places, and to hold the line long enough for photographers to memorialize the moment. “There was all kinds of frantic dashing around, getting the cards up front, trying to stop the movement of the crowd,” remembered John Morsell of the NAACP. The Big Ten amused each other by recounting the old line, “There go the people. I must follow them, for I am their leader.” Recalled Morsell, “If that joke was told once that afternoon, it was told a million times. Everybody felt it was the only appropriate thing to say.”21

Joining in song at the 1963 March on Washington. Photo by Leonard Freed

Three young women at the 1963 March on Washington in front of an unauthorized sign memorializing slain NAACP leader Medgar Evers. Photo by Marion K. Trikosko

There were, in fact, plenty of other things one could say about that moment. You might even call it a synecdoche for the March on Washington’s relationship to the larger movement of the time. The march leadership had, in every sense, inserted themselves in a popular groundswell in order to steer it, and they could only do that by slowing it down and holding it back. The march was as much about constraining the unruly energies of the grassroots as it was about applying pressure on the Kennedy administration, channeling vast anger and frustration into something as neat and bounded as a preprinted picket sign, in the hope that doing so would make the appeal for change impossible to ignore or reject. In a 1964 essay, SNCC organizer Michael Thelwell reflected on the march: “On the one hand, there was an undeniable grandeur and awesomeness about the mighty river of humanity, more people than most of us will ever see again in one place, affirming in concert their faith in an idea, and in a hope that is just.” But, he continued, “It is sad that at the end of so much activity, the best and worst that could be said is that ‘it was orderly and no one was offended.’”22

Lining up the leaders in the midst of the march. Roy Wilkins of the NAACP and A. Philip Randolph are at the far right.

The march in progress. Photo by Warren K. Leffler

Though the 1963 March on Washington is widely treated as the epitome of the big protest march in America, there never would be another one quite like it. No other protest would serve as a movement touchstone in quite the same way that that march has done for the Black freedom struggle. No other protest would be sanctified and mythologized to the same degree, either; every sizable subsequent mobilization would be compared to the 1963 March on Washington and somehow found to fall short. There would never be another demonstration in America that people would so emphatically credit with achieving a major legislative goal, even though the claim is a stretch at best, and no subsequent protest would be shaped and tamed so extensively by a sitting president and his administration. No one would ever try to stage manage a large crowd of demonstrators so tightly again, and no large crowd would again cooperate so willingly with being cast in such a scripted role. The flawless execution of the event on that August day in 1963 meant that future organizers would not have to contend with quite the same barriers of fear. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom opened up both literal and metaphorical space for political action, in ways that constitute one of its most enduring contributions. If that initially came only through highly respectable and stage-managed means, it set a precedent for mass protest, and mass assembly, that future movements would build on. By the 2017 Women’s Marches, the hallmark of a successful mass mobilization would typically be the diversity rather than the homogeneity of the voices and messages on display.

The Fifth Avenue Peace Parade, one of the earliest sizable protests against the Vietnam War. The photo likely dates from the first event in October 1965.

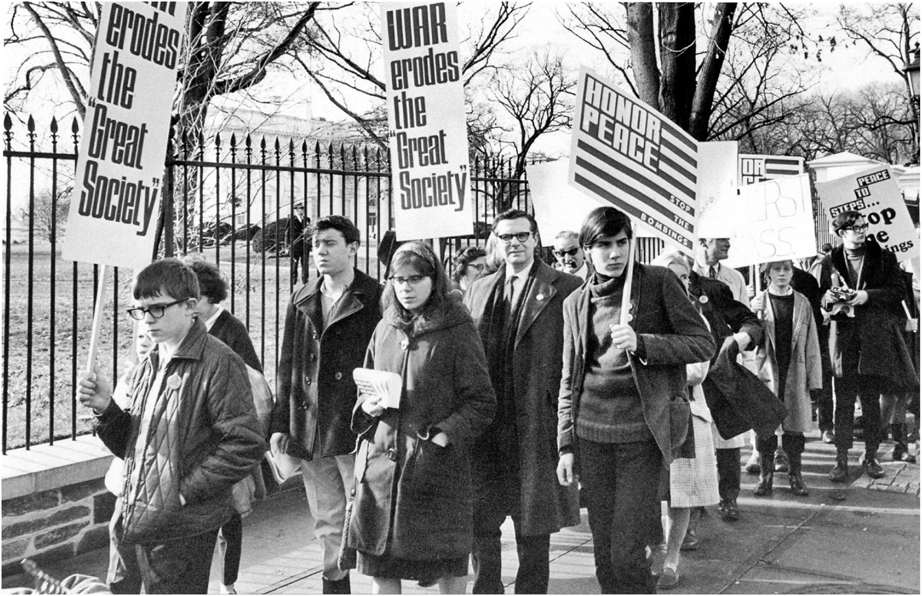

Certainly no one would ever again imagine they could completely control the signs at a major protest. There was a noteworthy attempt to do so at one of the earliest large protests against the Vietnam War, the October 1965 Fifth Avenue Peace Parade in New York. Organizers were so split over whether to call for an immediate military withdrawal from Vietnam or for negotiations to end the conflict that they ended up authorizing just one slogan for the event, a lowest-common-denominator message that all could support: “Stop the War Now.” Though the signs all said the same thing, in practice the march was far more freewheeling than the 1963 March on Washington. The culture of self-expression that would shape the New Left and its activist practice was already in evidence. Many participants didn’t just carry (approved) signs, but also expressed their political views through the political buttons they wore. Some wore skeleton masks and played musical instruments, and others carried evocative protest props like a blood-soaked Uncle Sam, pointing the way toward rich traditions of protest art that would develop in the years and decades to come. By November 1965, when the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE) organized the first major antiwar march in Washington, DC, the notion of controlling protest signs had been largely abandoned. SANE hoped to keep the messages of “kooks, communists or draft-dodgers” out of their march and compiled a list of seventeen acceptable slogans for the day. But they knew enough to bow to the evolving political realities of mass mobilizations. While SANE did have about two hundred march monitors on hand to request the removal of unauthorized signs or messages (a tenth the number of marshals at the March on Washington), they decided they would take no stronger action if people refused to comply. “We’ll just ignore them,” said march coordinator Sanford Gottlieb of unapproved slogans, “and they will just get lost in the crowd.”23

Demonstrators outside the White House at a November 1965 antiwar protest in Washington, DC. Photo by Theodore B. Hetzel

No big protest in America will ever look like the 1963 March on Washington again, with all the signs controlled by a central leadership. But you often see a sea of similar signs at large protests, and when you do, you’re usually seeing an organization flexing its muscles. (Advances in printing technology have also made it viable for individuals or small groups to shoulder the cost of large-format printing since at least the late 1980s, when the AIDS activist group ACT UP upended long-standing practices of protest signage with its bold and media-savvy designs; when you see uniformly printed signs at smaller protests, especially at direct actions, you’re often seeing groups that have consciously carried forward this newer tradition of art-directed activism.) When organizations have signs printed up for a big demonstration, they’re typically seeking to signal not just their message, but their organizational might and presence. Perhaps the signs were made by the sponsoring entity, whether a single organization or a coalition of multiple groups, and are publicizing the agreed-upon theme or demands of the event; perhaps they were made by coalition partners or cosponsoring groups and are showcasing their participation as well as their political stance.24

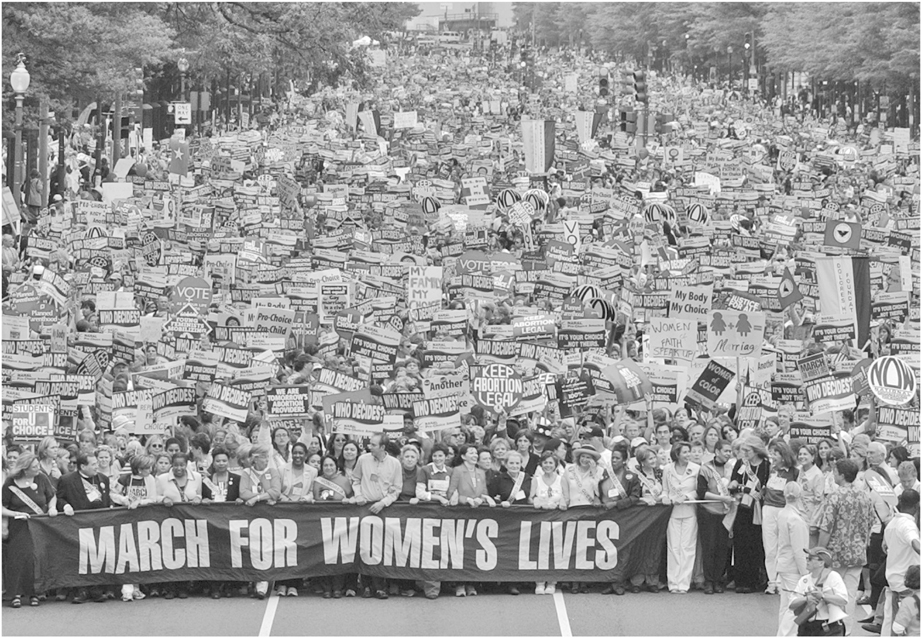

Colorful printed signs predominated, for instance, at one of the very largest protest marches ever to take place in Washington, DC, the enormous March for Women’s Lives in April 2004, a collaboration between the National Organization for Women (NOW), the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL), Planned Parenthood, and other established organizations. Turnout figures for this event are disputed, as they are for most big protests, but organizers could credibly claim that more than a million marched that day in support of women’s reproductive rights. The mobilization followed on the heels of a series of large pro-choice protests that NOW had organized in 1986, 1989, and 1992 in response to mounting threats to reproductive rights, leveraging its organizational resources time and again to bring impressive crowds to the streets of DC. Signs printed by NOW and its allies were foregrounded at each of these events. Instead of prohibiting messages they don’t like, organizations typically flood the crowd, and especially the highly visible lead contingent, with signs they’ve produced. (Nobody left a march step-off to chance again after 1963; organizers typically take special care to be sure they line up the front of their marches, usually with a special lead banner, before anyone starts moving.)

The 2004 March for Women’s Lives, one of the largest demonstrations ever held in the United States, gets ready to step off. Photo by Susan Walsh

It’s tricky, though, to assess a group’s real contributions from the signs featured at a protest. All you can tell for certain is that the group had a printing budget and enough staff or volunteer capacity to distribute posters. Signs can deceive. There are certain quite small but fervent organizations that reliably show up with big piles of posters at mass protests; the signs offer a way for them to promote their political analysis and, even more, to create the illusion of broader political support than they actually enjoy. More generally, unless you speak to the people who are carrying preprinted signs at a protest, you can never be sure whether they are active members of an organization who are proudly displaying their affiliation or just individuals who happen to be carrying signs that someone was handing out that day. Signs can advertise the presence of an organized contingent—say, members of a labor union or a faith-based group who came to a protest together and are showcasing their collective might—or they can give the impression of a greater degree of connection than actually exists. With each decade that has passed since the original March on Washington, there are fewer and fewer large organizations with a close and strong enough relationship to their base that they can directly mobilize their members. These sorts of locally rooted voluntary associations with robust member participation have been in steady decline since the 1960s, largely through slow attrition, though in some key cases (as with the labor movement in general, and the community organizing group ACORN) as a result of concerted right-wing attacks. They’ve been supplanted by what scholar Theda Skocpol describes as “professionally managed advocacy groups without chapters or members,” which have a top-heavy structure and whose work is driven by paid staff. This shift to what other critics have termed a “nonprofit industrial complex” has accelerated with the rise of digital organizing; these types of organizations typically have subscribers, followers, and donors, but few ways for supporters to participate more actively. A uniformity of signs at any protest brings a great clarity of message, but it can be difficult to discern how robust and resilient the underlying movement is, or if there’s a movement—instead of, say, an email list—represented there at all.25

The kind of popular power on display when organizations lead their memberships into action, as NOW did with its marches in the 1980s and early 1990s, may be muscular, but it is increasingly rare; few sizable organizations have memberships that are mobilizable in quite that way. Big mobilizations typically involve a more fragile and less predictable kind of popular power, and their success generally depends on the participation of large numbers of people who aren’t affiliated with any group. Even the 1963 March on Washington, typically thought of as the product of its sponsoring organizations, owed its then-unprecedented size to mobilizing the unorganized. Their participation likely accounted for at least half of the crowd who gathered in DC. On the eve of the march, transportation coordinator Rachelle Horowitz tallied up all the people planning to come to the event through official channels, and the number who had reserved seats on buses, trains, and planes through participating groups totaled 110,000. The extra margin of more or less spontaneous participation by some 140,000 other people—tens of thousands of DC locals, plus people who had arranged their own last-minute transportation—made the crucial difference between a solidly successful event and a gathering that was and felt truly massive. Even Horowitz’s tally gives a somewhat distorted impression of how the mobilizing worked. Although organizations like churches, civic groups, and NAACP chapters were responsible for lining up the transportation, a high proportion of their tickets were sold to unaffiliated individuals who had been moved to participate by news reports or other face-to-face outreach efforts like volunteer street leafleting. “People all kind of started calling up at the office,” Horowitz recalled. “In fact the March itself was not sending any buses, because we couldn’t you know worry about any bus captains collecting the money from individual fares. But people would be calling all the time, and I would continually have to tell New York CORE that they had to take another bus.” New York CORE and many other groups that arranged bus transportation sold a significant portion of the seats to people who weren’t official members but wanted a way to take part in the historic march.26

A marcher holds up one of hundreds of signs provided by the Human Rights Campaign Fund at the 1993 March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation. Photo by Howard Sachs

A crucial challenge for organizers in the wake of any big mobilization is how to absorb the new political energy and the new movement participants into some ongoing effort. Ideally, people should go home from a major demonstration not only with a feeling that they have played a role in something larger than themselves, but with a commitment to continued action and a clear sense of how they might contribute. For all the many ways in which the 1963 March on Washington can be considered an unqualified success, it’s worth noting that from the narrow perspective of movement building, its impact was at best muted, both for the organizations behind it and for the grassroots civil rights movement more generally. March organizers had a plan for bringing the waves of unaffiliated people who came to DC into movement organizations afterward: They distributed pledge cards, about 75,000 of which they collected from the crowd. Each of the six sponsoring organizations were given copies of these cards, in the hope that they would use them to expand their membership. Evidence suggests that the NAACP may have been the only group that managed to follow up, and they did so mostly by sending fund appeals. The NAACP’s membership ranks surged, but only briefly, and there’s little evidence that the march brought in many new active participants in the group’s local chapters. Many local groups were exhausted by the work involved in building participation for the march; the effort of mobilizing, ironically enough, seemed to demobilize ongoing grassroots work.27

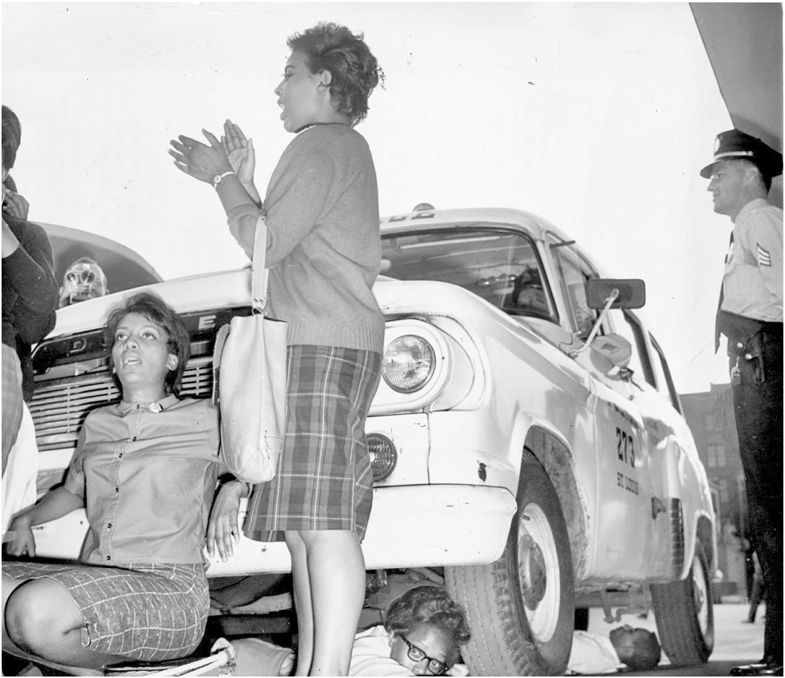

This sense of depletion was felt most strongly in the more direct-action-oriented parts of the movement, where enthusiasm for the march had been tempered with reservations from the start. Michael Thelwell of SNCC wrote in 1964, “The March became a symbol and a focal point in the minds of Negroes during this explosive summer of our discontent, and in many communities where the Negro temper was right, and where there had begun meaningful protest activity, the militants were diverted into mobilization for the March. . . . This happened in too many areas; local action slowed down, and we all looked to Washington for the climax that never came.” James Farmer, the national chairman of CORE, offered an even more pessimistic assessment in a 1967 interview: “I think we would have to say that the March sounded the death bell of the activist movement. Our chapters began to decline after the March and action began to decline. Many people who had been active said well we’ve done it, we really did it.” In his bitterness from the vantage point of four years later, when many felt the movement had reached an impasse, Farmer no doubt overstated the case. Some people went back home after the grand march and felt they’d done their part, but actions by CORE and other groups certainly continued. By fall, though, you could already sense a turn to stronger methods and angrier rhetoric in some movement circles, evidence of the climate of frustration and harbingers of the coming rise of Black Power. About a week after the march, for instance, protesters in Queens continued an ongoing campaign against discrimination in the building trades by breaking into a construction site and locking themselves to a crane. That’s the sort of tactic you use when milder methods like pickets—or mass marches—don’t seem to be working. (The judge who handled their case gravely declared, in what might be the first recorded instance of the march being used to chastise subsequent protesters, “The demonstrators in Washington were wonderful. You people are accused of flaunting the law daily in your demonstration.”) That October, young protesters who had been trying without success to pressure a St. Louis bank to hire more Black employees escalated their campaign by lying down in front of a police cruiser that was taking their fellow demonstrators to jail. The march had elevated and celebrated King’s dream of racial justice in ways that would inspire people for decades, but that didn’t mean its effects could be felt in the near term among those working at the grassroots to make the dream a concrete reality—a point worth bearing in mind when reading the snap assessments that follow any given protest.28

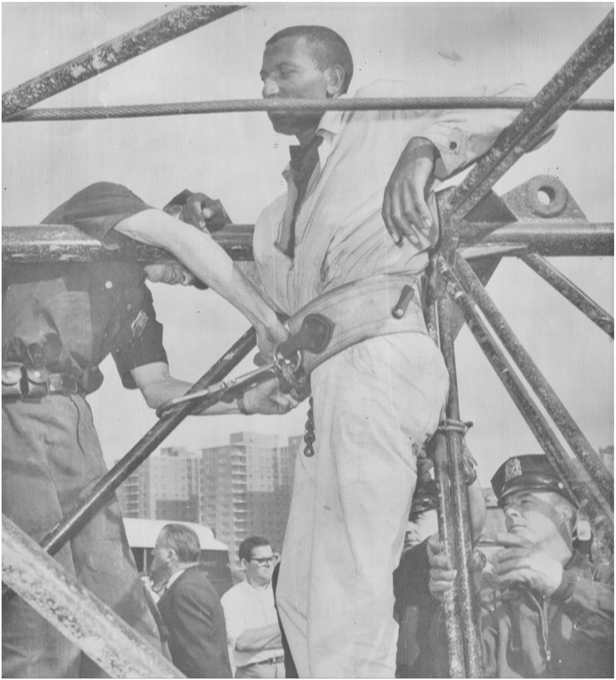

Police work to remove a protester locked to a construction crane in an action against hiring discrimination in the building trades, Queens, New York, September 1963.

Protesters block a police cruiser containing fellow demonstrators who were arrested during an action against hiring discrimination at a local bank, St. Louis, October 1963. Photo by Robert Larouche

The morning after the March on Washington, before the experience had hardened into myth, the New York Times described the event as “a day of sad music, strange silences and good feeling in the streets.” At the conclusion of the march, A. Philip Randolph read out the text of the pledge, in which marchers promised that they would “not relax until victory is won.” Then, for the first and only time at the carefully orchestrated event, the crowd was invited to speak. They were given three words to say, “I so pledge.” And then they went home, with posters in hand as souvenirs of a historic day that had pioneered mass protest in America, in majestic but massively controlled form. A US Information Agency film captured the carefully staged drama of the day, and turned it into overseas propaganda touting the strength of American democracy, even as the Kennedy administration continued to drag its heels on meaningful racial reform.29

The aftermath of the 1963 March on Washington. Photo by Leonard Freed

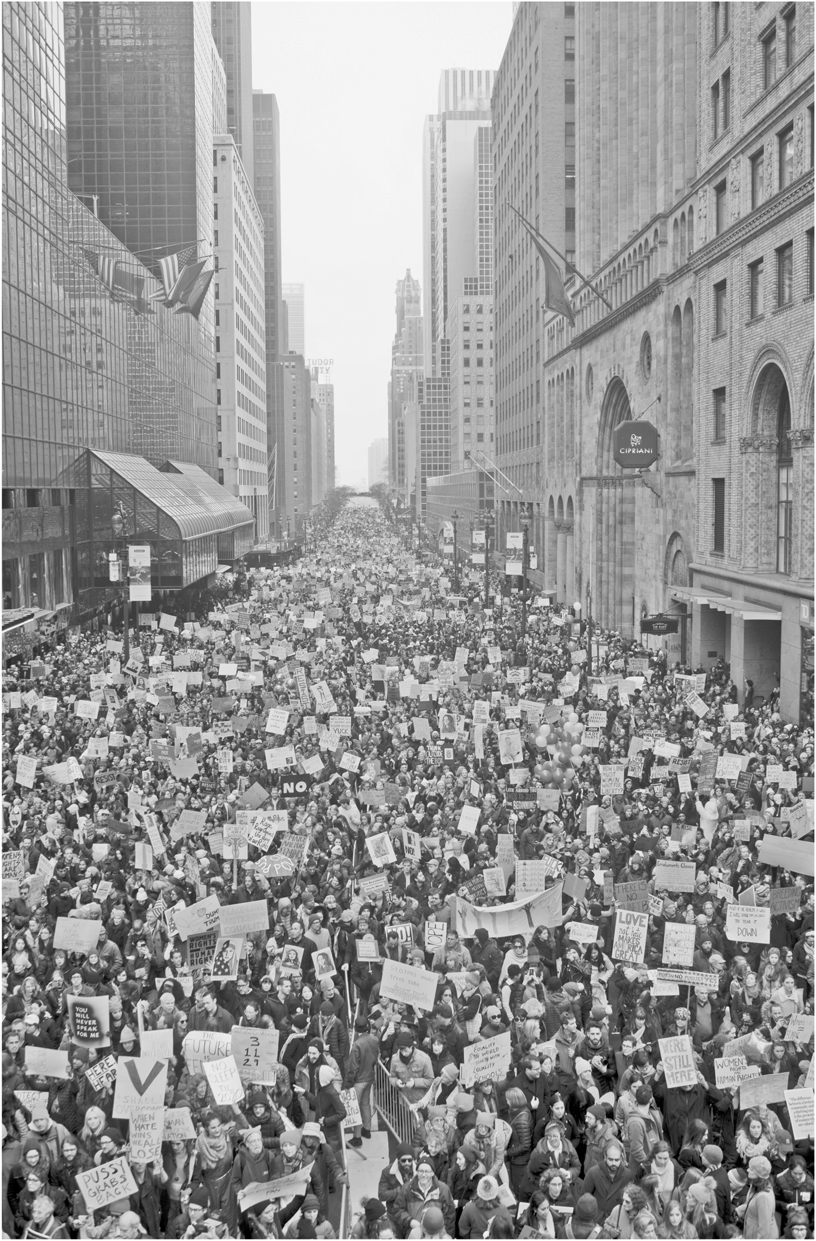

The 2017 Women’s March fills Forty-Second Street in New York. Photo by Carolina Kroon

Fast forward to January 21, 2017, the day after Donald Trump’s inauguration, when an astonishing 4.2 million or more people took to the streets in more than 650 coordinated Women’s Marches all around the United States. A great many large protests had happened in the interim, but this day of action was larger than any of them. Everything about the Women’s Marches, from the number of events to the overall turnout, broke or rivaled records for prior outpourings of popular dissent in America, making it almost certainly the largest coordinated protest ever in US history. The day’s hundreds of demonstrations were anchored by a major march in Washington, DC, that flooded the nation’s capital with 800,000 or more protesters. As such, the Washington component of the day ranked as one of the district’s largest protest gatherings, with a turnout at least three times greater than that of the 1963 march. Only three previous Washington protests—the 1993 Lesbian, Gay and Bi March on Washington, the 1995 Million Man March, and the 2004 March for Women’s Lives—rivaled it in size. The DC event was so immense that organizers never quite corralled it into a single, unitary march; crowds flowed like water through the streets and open spaces of the city. All around the country, turnout for the local “sister marches” ranged from solid to stunning: A crowd of 100,000 marched in Denver, and some 650,000 filled the streets of Los Angeles. In Chicago, the crowd of at least a quarter million was so large that city officials said it would be unsafe for them to march, but people marched anyway, peacefully overwhelming the Loop and many city streets. In New York, people were packed so tightly that they could barely make their way across town, and the march stalled repeatedly from human gridlock. In many smaller locales, turnout was the highest for any demonstration ever staged there. At least 10,000 people assembled in Reno, Helena, and Lansing; around 15,000 marched in St. Louis and Nashville; while in St. Petersburg, Florida, the crowd topped 20,000. Many small towns witnessed impressive turnouts for their size: 320 in Kodiak, Alaska, a town of just over 6,000; and 700 in Sharon, Pennsylvania, whose population is roughly 13,000.30

The 2017 Women’s March in Kodiak, Alaska. Photo by Judy Heller

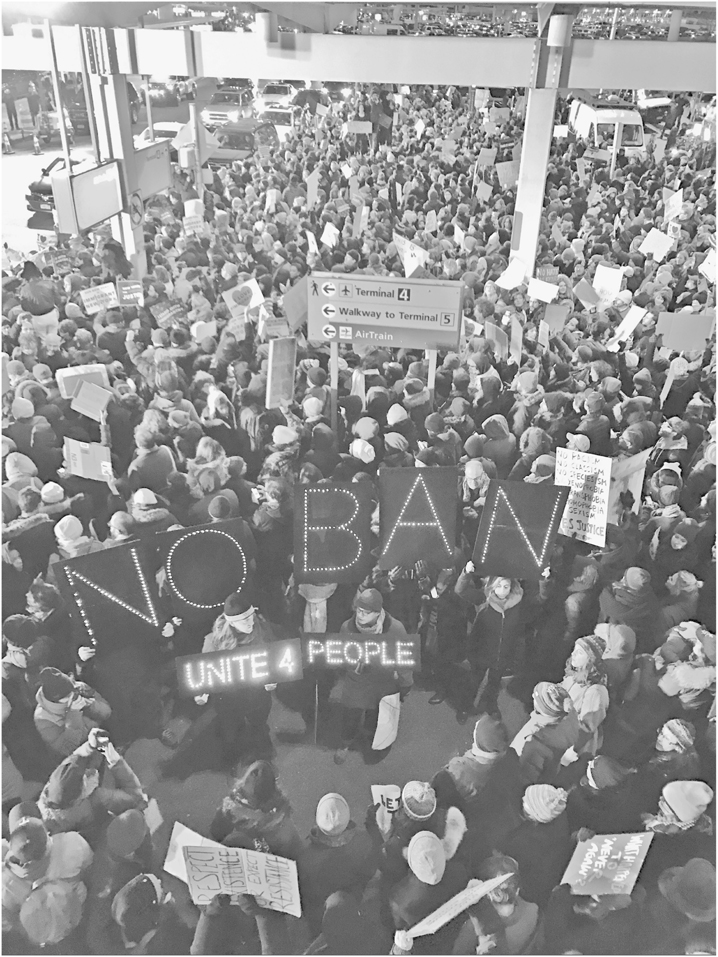

Their scale, though, was only one quality that set the Women’s Marches apart from previous big mobilizations in US history. The most obvious difference, of course, was that these were Women’s Marches. Washington had certainly witnessed feminist mobilizations before, including a march for the Equal Rights Amendment in 1978 and the series of major reproductive rights demonstrations that culminated with the enormous March for Women’s Lives in 2004. But these events were all far more narrowly focused than the huge outpouring in 2017. The Women’s Marches were led and shaped by women, but with a sweeping and inclusive agenda of issues that cut across demographic lines. That composition and breadth of focus would carry over to every aspect of the resistance to Trump, a sprawling movement of movements that has been overwhelmingly composed of women. As they marched, women were, in essence, laying claim to leadership of the left, staking out political space for a broad grassroots progressivism with feminism—and the much-maligned identity politics—at its core. In the year after Trump took office, women constituted a majority at protest after protest. When it came to grassroots organizing, the gender gap was even greater. The thousands of local resistance groups that sprang up to oppose Trump and Trumpism were typically started by women, and women often constituted 70 or 80 percent of their active membership. Women made some 86 percent of protest phone calls to Congress in the months after the new president took office and also took the lead in using stronger resistance tactics, from blockading Trump Tower in support of immigrant rights to holding sit-ins at Senate offices to defend access to health care.31

Sea of signs at the 2017 Women’s March in Madison, Wisconsin. Photo by Paul McMahon

If you glanced at any one of the 2017 Women’s Marches, you could read this women-led, multi-issue character in the powerful signs that people displayed. In a striking contrast to the 1963 March on Washington and most past major protests, those who took to the streets in such impressive numbers in 2017 mostly carried signs that they had carefully and thoughtfully made themselves. Instead of one single slogan or set of approved messages, there was an exuberant array of sentiments, giving a rich sense of the priorities of the crowds: “Women Rise Up,” “My Body My Choice,” “White Silence = Violence,” “Trans Lives Matter,” “Democracy for All,” “Feminism Must Be Intersectional,” “Hear Our Voice,” “None of This Is Normal,” and thousands upon thousands more. People made posters celebrating values and principles: democracy, diversity, equality, justice. They displayed messages of love and peace and connection, alongside angry insults aimed at the new president and his enablers.

Environmentalism, immigrant rights, racial justice, climate justice, and lesbian, gay, and transgender rights were all featured, signaling the presence of movements that had arisen or persisted during the Obama years, such as Black Lives Matter and the nationwide anti-pipeline movement sparked by Native American resistance at Standing Rock. Plenty of people made their hand-lettered march signs at home alone before the event, but many gathered for poster-making parties that prefigured the decentralized, locally based organizing that would characterize the resistance going forward. People gathered to make signs at churches in Anchorage, Alaska, and Grand Rapids, Michigan, and at public libraries in Tucson, Arizona, and New Haven, Connecticut. They decorated posters at a yoga studio in Helena, Montana, and at a pop-up bookstore in Miami, Florida. The signs were so creative and so full of heart and passion that taking in their messages and spirit became one of the most memorable aspects of the day. Slideshows of signs were everywhere on the internet, and two quick photo compilations were published soon after (both benefiting feminist and progressive nonprofits) to “serve as beacons of vigilance and hope,” in the words of Najeebah Al-Ghadban, the designer of one of the books. Numerous museums, including the National Museum of American History and the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts, collected signs from the marches to preserve as part of their collections.32

Above and beyond the many slogans they featured, the signs’ handmade character sent its own signal, reflecting a do-it-yourself quality that shaped the entire mobilization, from the way the marches first popped up on Facebook to the crowdsourcing apps that people used to make bus reservations, bypassing a key role—renting and filling buses—that organizations had traditionally played in protests. Of course there were preprinted posters sprinkled through the crowds, just as there were buses chartered by groups in the traditional way. The National Organization for Women, Planned Parenthood, the American Civil Liberties Union, and numerous other established organizations threw their weight behind the march organizing, and advertised their involvement by handing out signs at some of the marches. A number of labor unions, including the Service Employees International Union and UNITE HERE, mobilized contingents that featured their signs. The Women’s March national team held a design competition and had official posters printed up featuring the winning entries, and artist Shepard Fairey adapted his famous 2008 Barack Obama “Hope” poster into three designs for the occasion. But in city after city, so many people decided to make their own signs for the Women’s Marches that retailers had trouble keeping art supplies in stock that month. Sales of foam-core boards soared by 42 percent over the previous year, and sales of paint markers jumped by 35 percent. In just the week before people marched around the country, some 2 million poster boards were sold nationwide.33

The 2017 Women’s March in Los Angeles. Photo by Brendan Buckley

Trio of protesters at the 2017 Women’s March in St. Louis. Photo by Carrie Zukoski