Cinnamon Raisin Biscuits (vegan)

Oven-roasted Garlic for Bread Spread (vegan)

No-knead Dutch Oven Artisan Bread (vegan) (Roger Doiron)

Homemade Pitas and Pita Chips (vegan)

My wife had me long before hello — or good morning. The aroma of freshly baked muffins will do it every time.

Like scents wafting through the house, beckoning us to the breakfast table, the concept of sustainability appeals to our sense of personal responsibility, accounting for how we live, treat others and make a living in relation to the planet that nurtures us. Trusting intuition and our personal experience, drawing more from our experiential knowledge than an overload of facts or figures, leads us to recognize that we’re a vital part of the web of life. This ecological connection helps us become better stewards and eaters.

Sustainability is an ideal, a moving target, something we’re always working toward and improving upon. It touches not just on food and agriculture, but energy use, land stewardship, transportation and waste — recognizing that we live within an interdependent and interconnected living system. Organic farmers know this, motivated less by profits and more by nourishing fellow beings while simultaneously restoring and improving the soil, water and air. In practice, sustainable living is less about the growth of property, wealth or stuff and more about valuing diversity and cultivating a passion for restoration. It’s about creating local livable communities and fostering greater social and economic equity while preserving, and ideally restoring, the ecosystems upon which we depend for our very survival.

Our personal knowledge is not the same thing as “common knowledge,” the flow of sound bites from “experts” in the media or government. The vast majority of food imported into the US has never been inspected. Thousands of chemicals, many approved for use in food products by the US FDA, have contentious and often-conflicting research studies associated with them. But farmsteadtarians tend to operate under a version of the precautionary principle: when in doubt about what’s in it or where it’s from, don’t eat it. We don’t need to prove its harm before we take evasive action. There are more than 80,000 chemicals which are not fully studied or not studied at all, according to Urvashi Rangan at the Consumers Union, publisher of Consumer Reports. “Freedom” is not the fifty brands of cereal on the supermarket shelf — it’s understanding exactly what we’re eating; knowing that it’s nourishing and safe; that it was harvested by fairly paid workers who didn’t have to don a gas mask to work in the field.

While we can live more self-reliantly, we cannot live independently. Nature thrives on interdependences, with different species filling niches and maintaining symbiotic relationships. Our human species is not apart from this natural order, but a key part of it. Our life depends on several inches of topsoil with plenty of earthworms and micro-organisms, some sunlight and enough rain. Without the honeybees for pollination, about a third of all our food crops would be dust. Without enough rain, ditto.

There’s no way around it, sustainability cannot be used in the same sentence as development, infinite growth and rampant consumerism, upon which the present global economy is based. Sustainable agriculture, then, closes ecological loops; restores and improves topsoil, air and water; localizes production; and respects farmers, rather than exploiting them. Robert Rodale, founder of the Rodale Institute, called it “regenerative agriculture.” Those corporations proclaiming that we can “produce more, conserve more” are counting on enough people who have lost their connection to the land and those who work it to mask their profit motives and the kind of agriculture they foster instead: chemical-laden, large-scale, oil-addicted, genetically modified, industrial.

When baking, kneading is the step where it’s all hands-on. You’re turning over the dough, working it to make it more flexible and helping to distribute the yeast and other ingredients to form gluten, giving bread its texture and elasticity. There’s no exact start or end time to kneading. It’s done when you say so. Some of us will work vigorously and have a rhythmic technique, while others excel at pushing around the pile of flour and water for seemingly an eternity. Either way, kneading could be likened to mixing a pallet of watercolors — based on the eye of the beholder. Like sustainability. We know we need it, but how we get there is in our hands (as opposed to corporations or the government).

Courtesy of Kitchen Gardeners International

Most recipes are approximations — a pinch here and a dash there. Everyone has a different palate and preferences for sweet, sour, bitter, salty and savory. If you don’t care for the hot, acrid taste of horseradish, just try the recipe without it.

But baking is different — it demands exact measurements. Otherwise the bread won’t rise, yeast won’t react, and those glutens go flat. Not all recipes in this chapter have this trait, but some do.

Any way you bake it, the planet needs us as much as we need her. We’re a part of the tapestry of life, as imperfect or immeasurable as it may be.

CALL US THE Johnny Appleseed of muffin distribution. Where Johnny planted orchards as he wandered Ohio, we scatter muffins, sending some home with guests or dropped off with friends in town. There’s something about giving away things unexpectedly that instigates change. Drop a seed and something might grow. Give a friend a muffin and maybe they’ll linger and talk over a cup of coffee. These Applesauce Muffins blend Johnny Appleseed inspiration in bread form. Bake some and share.

1t. canola oil

2c. flour

½T. cinnamon

½T. allspice

1t. baking soda

½c. butter, softened (1 stick)

1c. sugar

1egg

1c. applesauce

1T. vanilla extract

½c. raisins

Lightly oil 12 standard muffin cups.

Lightly oil 12 standard muffin cups.

In a large bowl, combine flour, cinnamon, allspice and baking soda.

In a large bowl, combine flour, cinnamon, allspice and baking soda.

In another bowl, cream butter and sugar. Beat in eggs, applesauce and vanilla. Stir into dry ingredients until just moistened. Fold in raisins.

In another bowl, cream butter and sugar. Beat in eggs, applesauce and vanilla. Stir into dry ingredients until just moistened. Fold in raisins.

Fill prepared muffin cups almost full.

Fill prepared muffin cups almost full.

Bake at 350° for 20 to 25 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean. Let cool for about 10 minutes before removing from pan and placing on wire rack.

Bake at 350° for 20 to 25 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean. Let cool for about 10 minutes before removing from pan and placing on wire rack.

YIELD: 12 muffins.

By buying bulk bags of organic flour (and sugar) through a local buying club or food cooperative, we never run out and we save money. Our organic flour comes from Heartland Mills, a farmer-owned company based in Kansas; it’s unbleached and unenriched. Typical commercial processing of wheat into white flour extracts a lot of the good nutrients; therefore, the millers have to chemically add back in the nutrients, hence enriching the flour. Enriched flour breaks down faster in your body causing elevated blood sugar levels. Organic flour companies like Heartland Mills use minimal processing, therefore they don’t need to enrich and add the good stuff back in. The flour (and sugar) can be used as a one-for-one replacement for refined sugar or enriched flour in any recipe.

BECOME A FRUIT FORAGER wherever you may live. Every early September, Mary Frantz calls us: “The pears are ripe. Come pick.” Retired doctors, Mary and her husband John live in town and keep up the most prolific backyard urban homestead we’ve ever seen. They have more pears than they know what to do with, and we’re happy to put the fruit to good use. We bet there’s probably a tree you see every year in a yard near your home that overflows with fruit. Be a forager and rekindle community relationships by knocking on the door of its owner and ask to pick the tree; chances are your neighbors will be thrilled to know the fruit is going to good use rather than rotting on the ground. Then pay it forward. Return after the harvest bearing fruit pies or muffins to share, and you’ll come to embrace the grace that results from your community’s abundance. These muffins pair ginger with fresh pears, creating a fall flavor that can only be savored during the harvest season.

1t. canola oil

2c. flour

½c. brown sugar, firmly packed

2t. ginger

1t. baking soda

1t. cinnamon

1½c. fresh pears, peeled and finely chopped

½c. raisins

½t. salt

⅛t. nutmeg

⅛t. cloves

1egg

1c. plain yogurt

½c. vegetable oil

3T. molasses

Lightly oil 18 standard muffin cups.

Lightly oil 18 standard muffin cups.

In a large bowl, combine the first ten ingredients. In another bowl, beat the egg, yogurt, oil and molasses until smooth.

In a large bowl, combine the first ten ingredients. In another bowl, beat the egg, yogurt, oil and molasses until smooth.

Stir the wet ingredients into the dry ingredients until just moistened. Fold in pears and raisins.

Stir the wet ingredients into the dry ingredients until just moistened. Fold in pears and raisins.

Fill prepared muffin cups almost full.

Fill prepared muffin cups almost full.

Bake at 400° for 18 to 22 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean. Let cool for about 10 minutes before removing from pan and placing on wire rack.

Bake at 400° for 18 to 22 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean. Let cool for about 10 minutes before removing from pan and placing on wire rack.

YIELD: 18 muffins.

A NOT TOO SURPRISING CONFESSION: we love chocolate. But as we learned more about sustainability and Fair Trade issues, our chocolate options grew leaner and more expensive. Organic Fair Trade chocolate chips are hard to find, expensive and, we grudgingly admit, not a necessity of life. Our next best option is cooking more with baking cocoa, supporting companies like Equal Exchange. Much less expensive and processed than those chips, baking cocoa contains more of the good health benefits of chocolate, like antioxidants to lower blood pressure and cholesterol. A bonus with these muffins: Their taste closely resembles that of their cupcake cousin, so you can also pour the batter into a 9-inch cake pan (you may need to bake it a little longer) for a special birthday cake.

1t. canola oil

1½ c. flour

1c. sugar

1t. baking soda

½t. salt

3T. cocoa powder

1t. vinegar

⅓c. vegetable oil

1t. vanilla

1c. water

1T. powdered sugar

Lightly oil 12 standard muffin cups.

Lightly oil 12 standard muffin cups.

In a large bowl, combine all ingredients.

In a large bowl, combine all ingredients.

Fill prepared muffin cups until almost full.

Fill prepared muffin cups until almost full.

Bake at 350° for about 20 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean.

Bake at 350° for about 20 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean.

Let cool for about 10 minutes before removing muffins from pan and placing them on a wire rack.

Let cool for about 10 minutes before removing muffins from pan and placing them on a wire rack.

To serve, place on serving plate and dust with powdered sugar.

To serve, place on serving plate and dust with powdered sugar.

YIELD: 12 muffins.

Mother Earth doesn’t charge a penny for her fruits. Money is our invention, not hers, though to listen to many people you’d think it had the same status as water, food and oxygen. There is food for free everywhere. You just need to know where to look and what to look for.

MARK BOYLE, THE MONEYLESS MAN

WE’VE FOUND A LITTLE MORSEL of something goes a long way, like chocolate chips. The unexpected sweet tidbits you’ll find when you bite into these muffins blend wonderfully with the other spices. In place of the winter squash, you can readily use pumpkin. The frozen pulp purée from either winter squash or pumpkin also works well in this recipe.

1t. canola oil

2eggs

1c. winter squash purée

½c. butter, melted (1 stick)

2t. cinnamon

½t. ginger

½t. nutmeg

½t. allspice

1t. baking soda

½t. baking powder

¼t. salt

¾c. sugar

1¾ c. flour

¾c. chocolate chips

Lightly oil 12 standard muffin cups.

Lightly oil 12 standard muffin cups.

In a large bowl, combine eggs, squash and butter.

In a large bowl, combine eggs, squash and butter.

Add spices, baking soda, baking powder, salt, sugar and flour. Mix until well-blended.

Add spices, baking soda, baking powder, salt, sugar and flour. Mix until well-blended.

Fold in chocolate chips.

Fold in chocolate chips.

Fill prepared muffin cups until almost full.

Fill prepared muffin cups until almost full.

Bake at 350° for 25 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean. Let cool for about 10 minutes before removing from pan and placing on wire rack.

Bake at 350° for 25 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean. Let cool for about 10 minutes before removing from pan and placing on wire rack.

YIELD: 12 muffins.

There is a great deal of truth to the idea that you will eventually become what you eat.

MOHANDAS GANDHI

THESE BISCUITS ARE DELICIOUS WARM AND FRESH. Not so, a few hours later. The recipe can be cut in half for smaller groups. Butter can be substituted for the margarine and regular milk for soy for a non-vegan version.

⅔c. soy milk (plain or vanilla)

1T. lemon juice or vinegar

2c. flour

¼c. sugar

2t. baking powder

1t. salt

¼t. baking soda

⅓c. vegan margarine (5½ T.)

⅓c. raisins

1½t. ground cinnamon

1t. canola oil

¾c. powdered sugar

1T. vegan margarine, softened

1t. vanilla extract 3 to 5 t. warm water

Place the 1 T. lemon juice (or vinegar) in a 1-cup glass measuring cup. Fill to ⅔ c. with soy milk. Let stand at least 5 minutes (milk will curdle).

Place the 1 T. lemon juice (or vinegar) in a 1-cup glass measuring cup. Fill to ⅔ c. with soy milk. Let stand at least 5 minutes (milk will curdle).

In a large bowl, combine flour, sugar, baking powder, salt and baking soda.

In a large bowl, combine flour, sugar, baking powder, salt and baking soda.

Cut in margarine until mixture resembles coarse crumbs.

Cut in margarine until mixture resembles coarse crumbs.

Stir in soy milk until mixture is just moistened.

Stir in soy milk until mixture is just moistened.

In the same bowl, sprinkle in raisins and cinnamon. Knead 8 to 10 times in bowl (cinnamon will have a marbled appearance).

In the same bowl, sprinkle in raisins and cinnamon. Knead 8 to 10 times in bowl (cinnamon will have a marbled appearance).

Form batter into 12 mounds, 3 inches in diameter and 2 inches apart on a lightly oiled baking sheet.

Form batter into 12 mounds, 3 inches in diameter and 2 inches apart on a lightly oiled baking sheet.

Bake at 425° for 12 to 16 minutes or until golden brown.

Bake at 425° for 12 to 16 minutes or until golden brown.

For frosting, combine the sugar, butter, vanilla and enough water to achieve desired consistency. Frost the warm biscuits then serve immediately.

For frosting, combine the sugar, butter, vanilla and enough water to achieve desired consistency. Frost the warm biscuits then serve immediately.

YIELD: 12 biscuits.

Most margarine contains trace amounts of dairy products such as whey or lactose. We use Earth Balance for our vegan recipes.

TALK ABOUT A MULTI-PURPOSE RECIPE. We cut this up as a coffee cake in squares for breakfast. If you take an afternoon tea break, skip the cookies and try this fruity option instead. Packed full of apples, it stays moist and works great for travel snacks. Drizzle the cake with warm Caramel Syrup (see page 191) and share it as a dessert after dinner.

½c. butter (1 stick)

2c. sugar

2eggs

6T. water

1t. vanilla

4c. apples, peeled and chopped (about 6 large apples)

2c. flour

2t. cinnamon

½t. nutmeg

½t. allspice

2t. baking soda

1t. canola oil

In a large bowl, cream butter and sugar. Add eggs one at a time.

In a large bowl, cream butter and sugar. Add eggs one at a time.

Mix in water and vanilla, then fold in apples.

Mix in water and vanilla, then fold in apples.

Mix together dry ingredients (flour, cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice, baking soda). Gently fold in dry ingredients to apple mixture.

Mix together dry ingredients (flour, cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice, baking soda). Gently fold in dry ingredients to apple mixture.

Pour into lightly oiled 9 × 13-inch baking pan. Bake at 350° for 1 hour.

Pour into lightly oiled 9 × 13-inch baking pan. Bake at 350° for 1 hour.

YIELD: 12 servings.

Both the Apple Coffee Cake and Peanut Butter Pumpkin Bread are quick breads — they don’t use yeast and therefore don’t need kneading and rise time before baking.

PUMPKINS AREN’T JUST for jack-o-lanterns. After growing New England Pie and Long Pie (we stack these elongated pumpkins on our front porch like cordwood), we discovered that these varietals glow with flavors, not candles. Who knew a silken pumpkin purée and peanut butter made such good partners? This loaf-style recipe yields two loaves; if that’s more than you need, these loaves freeze well or are always appreciated by neighbors. We’ve learned the hard way that lightly oiling and flour-dusting the pans are crucial steps to ensure the loaf smoothly pops out of the pan.

1T. canola oil

1T. flour (for dusting pans)

3c. sugar

2c. pumpkin purée

4eggs

1c. vegetable oil

¾c. water

⅔c. peanut butter

3½ c. flour

2t. baking soda

1½ t. salt

1t. cinnamon

1t. nutmeg

Prepare two 8 × 4-inch loaf pans by lightly oiling them, then dusting the inside of the pan with flour.

Prepare two 8 × 4-inch loaf pans by lightly oiling them, then dusting the inside of the pan with flour.

In a large mixing bowl, combine the sugar, pumpkin, eggs, oil, water and peanut butter. Blend pumpkin mixture well.

In a large mixing bowl, combine the sugar, pumpkin, eggs, oil, water and peanut butter. Blend pumpkin mixture well.

Combine the flour, baking soda, salt, cinnamon and nutmeg. Gradually add to pumpkin mixture; mix well.

Combine the flour, baking soda, salt, cinnamon and nutmeg. Gradually add to pumpkin mixture; mix well.

Pour into prepared loaf pans. Bake at 350° for 60 to 70 minutes or until a toothpick inserted into the centers comes out clean.

Pour into prepared loaf pans. Bake at 350° for 60 to 70 minutes or until a toothpick inserted into the centers comes out clean.

Cool for 10 minutes before removing from pans to wire racks.

Cool for 10 minutes before removing from pans to wire racks.

YIELD: 2 loaves.

It’s nutty. Peanuts are from the legume family, kin to pinto beans and lentils. Peanut butter provides plant proteins along with healthy non-hydrogenated fats.

WE WISH WE HAD highly acid soil on our farmstead to grow blueberries, but we don’t. Happily, some local growers have managed to cultivate wonderful crops of these luscious berries, and we purchase them by the quart whenever we get the chance. They have the highest antioxidant capacity of all fresh fruit, lots of vitamin C and may even be a natural belly fat buster. For this recipe, you can use fresh or frozen blueberries; if using frozen, do not defrost them. We use this dish as a morning coffee cake, but it can easily masquerade as an evening dessert.

3c. blueberries

⅔c. sugar

¼c. cornstarch

¾c. water

1T. lemon juice

2c. flour

1c. sugar

1T. baking powder

1t. salt

1t. cinnamon

¼t. nutmeg

1t. canola oil

1c. butter (2 sticks)

2eggs

1c. milk

1t. vanilla extract

½c. flour

½c. sugar

¼c. butter (½ stick)

In a saucepan, combine fruit, sugar, cornstarch and water. Over medium heat, bring to a boil. Stir constantly and boil for about 5 minutes or until thickened.

In a saucepan, combine fruit, sugar, cornstarch and water. Over medium heat, bring to a boil. Stir constantly and boil for about 5 minutes or until thickened.

Remove from heat and stir in lemon juice. Let cool.

Remove from heat and stir in lemon juice. Let cool.

Meanwhile, make crust. Mix flour, sugar, baking powder, salt, cinnamon and nutmeg in a bowl. Cut in butter until mixture looks like coarse crumbs. Beat together eggs, milk and vanilla. Add to flour mixture and mix well.

Meanwhile, make crust. Mix flour, sugar, baking powder, salt, cinnamon and nutmeg in a bowl. Cut in butter until mixture looks like coarse crumbs. Beat together eggs, milk and vanilla. Add to flour mixture and mix well.

Spread two thirds of the mixture into a lightly oiled 9 × 13-inch baking pan. It’s simplest to use clean wet hands to evenly spread the mixture into the pan.

Spread two thirds of the mixture into a lightly oiled 9 × 13-inch baking pan. It’s simplest to use clean wet hands to evenly spread the mixture into the pan.

Spoon fruit filling over crust to within one inch of pan edge. Top with remaining crust mixture.

Spoon fruit filling over crust to within one inch of pan edge. Top with remaining crust mixture.

For topping, combine flour and sugar in bowl. Cut in butter until coarse crumbs form. Sprinkle over top of cake.

For topping, combine flour and sugar in bowl. Cut in butter until coarse crumbs form. Sprinkle over top of cake.

Bake at 350° for about 1 hour or until lightly browned.

Bake at 350° for about 1 hour or until lightly browned.

YIELD: 12 servings.

Many different small berries, like raspberries, cloudberries, blackberries and black raspberries, can easily replace the blueberries in this recipe, making it quite versatile throughout the various berry-abundant seasons. The recipe will not, however, work well with strawberries due to their texture.

WE DID THE IMPOSSIBLE. Our first couple of years in the gardens, we killed our zucchini. So while everyone else in our town would lock their car doors in the summer for fear of their front seat becoming a depository for unwanted surplus, we left our doors unlocked — and windows open. After a few years working on our soil and realizing that the squash bugs were ruining our day, we’ve managed to join other growers with over-zealous crops. Thankfully, this muffin recipe blows through any varieties of summer squash or zucchini — eight balls, patty pans, curly necks — they all work well in this recipe, but it’s best to get the zucchini before they get too big.

1t. canola oil

1⅓ c. sugar

2eggs

1t. vanilla

3c. fresh shredded zucchini (or summer squash)

⅔c. butter, melted

3c. flour

2t. baking soda

¼t. salt

2t. cinnamon

1t. nutmeg

Lightly oil 18 standard muffin cups.

Lightly oil 18 standard muffin cups.

In a mixing bowl, combine the sugar, eggs and vanilla. Stir in zucchini and melted butter.

In a mixing bowl, combine the sugar, eggs and vanilla. Stir in zucchini and melted butter.

In a separate bowl, combine flour, baking soda, salt, cinnamon and nutmeg. Add flour mixture to zucchini mixture and blend well.

In a separate bowl, combine flour, baking soda, salt, cinnamon and nutmeg. Add flour mixture to zucchini mixture and blend well.

Fill prepared muffin cups until almost full. Bake at 350° for about 25 to 30 minutes or until a toothpick inserted in the center of the muffins comes out clean. Let stand for about 5 minutes before removing from pan and placing on a wire rack to cool.

Fill prepared muffin cups until almost full. Bake at 350° for about 25 to 30 minutes or until a toothpick inserted in the center of the muffins comes out clean. Let stand for about 5 minutes before removing from pan and placing on a wire rack to cool.

YIELD: 18 muffins.

LONG BEFORE THE BIG GULP, SUPER SIZE OR JUMBO PACK, there was the single serving: a portion meant to satisfy our appetite or quench our thirst, not overstuff or drown it. We take this same approach to anything with chocolate in it. With a high-quality baking cocoa, you just need enough cocoa — when prepared with rich farm-fresh eggs and our vanilla — to create decadent bread without having to use a whole bag of chocolate chips or a pudding mix in it. Like the Zucchini Muffins, any summer squash or zucchini will work in this recipe. This bread freezes well and can be quickly retrieved for those impromptu soup nights or potlucks.

1T. canola oil

1T. flour (for dusting pans)

3eggs

1c. vegetable oil

2c. sugar

1T. vanilla extract

2c. shredded zucchini (about 1 medium)

2½ c. flour

½c. baking cocoa

1t. salt

1t. baking soda

1t. cinnamon

¼t. baking powder

Prepare two 8-inch-by 4-inch-by 3-inch loaf pans by lightly oiling, then dusting the inside of the pan with flour.

Prepare two 8-inch-by 4-inch-by 3-inch loaf pans by lightly oiling, then dusting the inside of the pan with flour.

In a mixing bowl, beat eggs, oil, sugar and vanilla. Stir in zucchini.

In a mixing bowl, beat eggs, oil, sugar and vanilla. Stir in zucchini.

In a separate bowl, combine flour, baking cocoa, salt, baking soda, cinnamon and baking powder. Add flour mixture to zucchini mixture and blend well.

In a separate bowl, combine flour, baking cocoa, salt, baking soda, cinnamon and baking powder. Add flour mixture to zucchini mixture and blend well.

Pour into prepared loaf pans.

Pour into prepared loaf pans.

Bake at 350° for 1 hour or until a toothpick stuck in center of bread comes out clean.

Bake at 350° for 1 hour or until a toothpick stuck in center of bread comes out clean.

Before serving, let the bread fully cool for easier slicing.

Before serving, let the bread fully cool for easier slicing.

YIELD: 2 loaves.

|

Sprouting Hope with Your 100-foot Diet |

|

We should never lose hope, give up, toss in the towel when faced with a seemingly insurmountable problem/obstacle. We saw the movie, The Road, a disturbing look into a future where some undefined calamity forces a father and his son onto a road for their very survival. Their situation seemed hopeless, yet they kept moving forward, down the road. Around our town today, it’s not that bad, but some folks are without a job, without a house or without a family. Hope seems to be the buzzword of late. But to hope without action is like passion without a purpose — or planting seeds in poor soil, forgetting about weeding, watering and nourishing them with compost and care. As Anna Lappé and her mom, Francis Moore Lappé, like to say: “Hope is not what we find in evidence. It is what we become in action.”

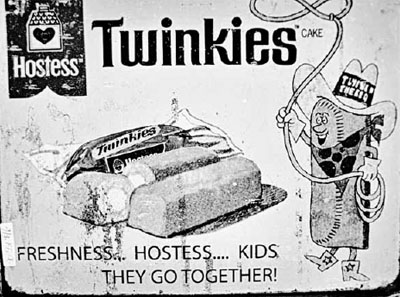

A sign of the processed times. “Fresh” Twinkies?

Every new growing season ushers in a hope for a great harvest by American gardeners now numbering into the millions, according to the National Gardening Association. With rooftop gardens, patio container plantings and backyard kitchen gardens, the 41 million Americans who grow at least some of their own food (12 million of them do it without any chemicals) are reclaiming the power that comes with being able to feed yourself and your family with little or no involvement from multinational corporations or government. Forget the 100-mile diet — say hello to the 100-foot (or less) diet.

In many parts of the country — including Detroit, Pittsburgh, Atlanta and San Diego — urban farmers are growing more healthy food than their farming folk in the country. This underground farmer movement has more Americans each day picking up the shovel and potato fork, starting a compost pile and growing some fruits, vegetables and herbs. Some of this growth stems from simple economics: it’s easier, more affordable and healthier to eat from our own gardens, for both us and the planet. This agriculture tradition is uniquely human, one that the corporate food industry has failed to extinguish.

At the turn of the 20th century, more than half of all American families worked the land. During World War II, more than half the US population (and many Canadians and Europeans, too) grew at least some of their food as a part of taking responsibility for their nourishment and to make a contribution to the war cause. Today, nearly 1 in 7 of us may grow a tomato plant, harvest basil from a potted plant or tend to a small flock of chickens in our backyard. And millions more are getting into the game before their food stamps run out. As we quickly discovered: plant a seed in the spring and witness the miracle of nature’s abundance as your countertops overflow with cucumbers, tomatoes and, of course, zucchini.

Sunlight, access to a water supply, some soil and a little space is all that’s needed to get started with your own garden. You’ll quickly discover that there are many organic gardening strategies that help add a bump to your bumper crops, including building your soil with compost, rotating crops to deter garden pests and preserve soil balance and mulching for weed control and moisture retention. But the most important thing for organic growers is keeping the natural-gas-derived and oil-based chemicals out of the gardens and away from your food by avoiding synthetic fertilizers, fungicides and insecticides. Organic growing means that nothing is being poisoned: not the soil, the water, the farmers or the eaters. It’s farming with nature rather than waging war against it.

More and more research has emerged documenting, too, that crops grown organically have higher levels of minerals, nutrients and, most important to any great cook, flavor. Flavor remains the most compelling reason to grow, and eat, organically, ideally from produce grown or raised nearby where you live. Less than a 100 feet from your back door is best.

There are many approaches you may take to growing some of your own food, such as:

French-style intensive raised beds: It’s a favorite of ours, since it builds soil tilth: the soil structure that’s nutrient dense and loose, airy and crumbly. It also efficiently uses a small space to produce a large yield of edibles. Soils vary by geography and climate, but all soils have a mixture of clay, sand and organic matter to meet the growing needs of the plants. Raised beds help focus your energy into nutrient-rich soils, minimize soil compaction (which prevents root systems from developing) and, because the beds can be built above ground with a wooden framework, reduce the backbreaking efforts of gardening. Our raised beds are four feet wide, double-dug and mounded, increasing the depth of the soil that helps the plants thrive better.

Permaculture-designed gardens: A term coined by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren, permaculture is the melding of permanent human settlements and agriculture, creating designs based on viable, natural ecological systems where what’s produced by one element of the system becomes the input for another. The ethics of permaculture are simple: care for people, care for the planet and share the surplus. In nature there is no waste, so permaculture-inspired gardens recycle or reuse all nutrients and energy sources, regenerating natural systems while boosting the self-sufficiency of human settlements and reducing the need for industrial production systems that demand cheap, polluting energy sources to thrive. “We’re not stealing from nature, we’re actually providing for it,” explains permaculturalist Mark Shepard with Forest Agriculture Enterprises, where he has created a food forest on his farm in Wisconsin through permaculture design. Plants are selected and planted according to how they help one another. Free-ranging chickens, for example, can help fertilize, work up the soil and control insect pests while providing nutrient-packed eggs (we humans provide shelter, security, a water source and supplemental food in the winter). There are numerous go-to places for more information, including the Permaculture Activist (permacultureactivist.net) or the Urban Permaculture Guild (urbanpermacultureguild.org). For a more personal, hands-on experience, consider taking one of the growing number of permaculture design courses, perhaps from Midwest Permaculture (midwestpermaculture.com), Glacial Lakes Permaculture (glaciallakespermaculture.org) or the Esalen Institute (esalen.org).

Lasagna gardening: A no-till, no-dig approach to planting a garden, particularly suitable if you live in a suburb where grassy lawns are abundant. The gardens can be of any size or shape, but involve placing layers of organic material such as leaves, grass clippings and old newspaper that will decompose to create a rich, loose soil perfect for growing plants of any kind. The first layer is always cardboard or several sheets of newspaper, to smoother the grass or weeds underneath. After that, it’s basically a compost pile, with earthworms working their magic as they wiggle their way up through the decomposing matter. For more about lasagna gardening, visit www.no-dig-vegetablegarden.com.

Container planting.

Container planting: Almost any container can be used to grow fruits, vegetables or herbs for fresh, seasonal cooking, from large flower pots to old wooden barrels. With a sunny enough patio or rooftop space, you’re good to go. Five or more hours of direct sunlight a day is needed for proper growth for most plants, but many plants, such as tomatoes, require more. Whatever container you use, make sure there are holes at the bottom to allow the water to drain out (cover with old cracked ceramics, terracotta pots or newspaper) and start out by using an organic “soilless” potting mix that’s appropriate to your plant’s needs (some plants need more sand, compost or the soil to be more or less acidic). Along with sunlight, mindfully watering the plants (containers often lose moisture quickly) and adding fertilizer (an organic liquid fish emulsion works great) based on the types of plants grown is a must. For more, check out From Container to Kitchen, by D. J. Herda.

New gardening approaches come about as more of us explore new ways to meet our daily food needs. In New York City, for example, Homegrown Harvest founders Rebecca Bray and Britta Riley manage to use the available window space in apartments and condos to create a prolific vertical garden year-round with a hydroponic system. They call it window farming (windowfarms.org). If you don’t have enough windows, try growing something on the roof, like they do on the Eagle Street Rooftop Farm, a 6,000-square-foot farm atop a warehouse in Brooklyn, New York (rooftopfarms.org). For a more general introduction to farming in the city, check out Urban Farm Online (urbanfarmonline.com) or in Canada, City Farmer News (cityfarmer.info). Community gardens are transforming empty city lots, church lawns and schoolyards into a cornucopia of fresh food; go to the American Community Gardening Association (communitygarden.org) to find one near you.

We use organic or heirloom seeds — seeds that are passed down from numerous generations with unique characteristics, most notably flavors, colors or shapes. Great sources for seeds to get your gardens underway include: Fedco Seeds or West Coast Seeds, for a wide selection of affordable organic and heirloom seeds (fedcoseeds.com and westcoastseeds.com); Seeds of Change, for over 1,200 varieties of organic seeds (seedsofchange.com); Seed Saver Exchange, for heirloom, mostly organic, seeds from fellow gardeners dedicated to saving and sharing heirloom seeds (seedsavers.org); Johnny’s Selected Seeds, offering a wide selection of certified vegetable, herb and flower seeds (johnnyseeds.com); National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service, for a directory of organic seed suppliers (attra.ncat.org). Most local garden supply stores sell organic growing media for container plants, or can special order it for you.

As for what to grow, try something — anything. You might start with what grows best in your part of the country. The USDA breaks the country down into growing zones that reflect the frost dates and historical weather patterns that dictate what will, and will not, survive or thrive in your area. Cross-reference this zone number with the seed packets you’re considering. An easier and simpler option: talk to neighbors or the farmers at your local farmers market and take advantage of their knowledge.

Space is usually a limitation, so consider this when planning your garden. You’ll need plenty of sunlight and have a source of water for irrigation. Soil quality can be built up over time, but it helps that you have a supply line for compost or garden waste (a local restaurant or coffee house may happily assist). It’s natural to grow what you love eating, like tomatoes, and avoid going overboard on crops that may overwhelm you on their prolific fruiting potential, like zucchini or cucumbers. We started by focusing on what we love to eat and what we eat the most of. For those in the city or suburbs challenged with space, you may want to grow what’s least available fresh or affordable, like basil, which is rather pricey for small, one-ounce packages; growing your own makes pesto affordable and flavorful — and it’s something that freezes well so can be savored year-round.

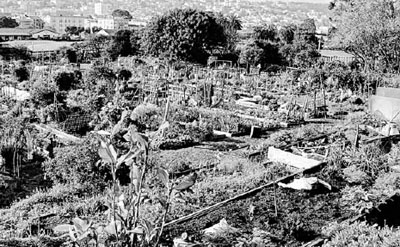

Community gardens in… San Francisco (top) or Santa Monica (bottom).

OKAY, SO IT’S NOT A BREAD RECIPE. This garlic recipe is the best way to savor a freshly baked French Baguette (see page 55) — and the mouth-watering aroma will fill your house in the most delicious way. Garlic is a wonder plant, if there ever was one; it boosts our immune system, among many other benefits, and can help ward off a cold. It’s a prebiotic, an important bacterial fuel for the beneficial probiotic bacteria that help maintain our intestinal health. To make the roasted garlic, we have an enclosed terra cotta baking dish we use for roasting garlic, but any shallow, covered casserole dish will do.

4whole garlic heads (not cloves)

2T. olive oil

1½ c. water

Using a sharp knife, cut the top of the garlic head to expose the inner cloves.

Using a sharp knife, cut the top of the garlic head to expose the inner cloves.

Brush heads with olive oil and place in a shallow casserole dish. Fill dish with 1 inch of water and cover.

Brush heads with olive oil and place in a shallow casserole dish. Fill dish with 1 inch of water and cover.

Bake at 350° for 45 to 60 minutes until garlic is very soft and light brown. Check garlic for softness since oven temperatures may vary.

Bake at 350° for 45 to 60 minutes until garlic is very soft and light brown. Check garlic for softness since oven temperatures may vary.

Serve with French baguette slices. To eat, remove the garlic from its skin with a knife and spread onto baguette rounds with butter.

Serve with French baguette slices. To eat, remove the garlic from its skin with a knife and spread onto baguette rounds with butter.

YIELD: 4 servings.

Tomatoes and oregano make it Italian; wine and tarragon make it French. Sour cream makes it Russian; lemon and cinnamon make it Greek. Soy sauce makes it Chinese; garlic makes it good.

ALICE MAY BROCK

FRITTERS BRING SMILES, and they’re the ultimate winter comfort food. Any combo of winter squash works well, like butternut or acorn. The fritters make a nice accompaniment with a savory breakfast or as a side with soups. Serve with a honey-mustard dipping sauce.

1c. winter squash purée

1egg

¼c. onion or chives, chopped

1c. corn

½c. self-rising flour

½c. self-rising cornmeal

1t. sugar

½t. salt

6c. canola oil (for frying)

1c. honey

1T. Dijon mustard

In a bowl, combine the squash, egg, onion and corn.

In a bowl, combine the squash, egg, onion and corn.

In another bowl, combine dry ingredients of flour, cornmeal, sugar and salt; add dry ingredients to squash mixture and beat well.

In another bowl, combine dry ingredients of flour, cornmeal, sugar and salt; add dry ingredients to squash mixture and beat well.

In a skillet (an electric skillet works well) or deep fryer, heat ¼ inch of oil to 400°. Drop about ⅛ cup of batter and cook about 4 minutes or until crisp and golden, turning often. Cooking time will vary based on frying temperature. Drain on paper towels.

In a skillet (an electric skillet works well) or deep fryer, heat ¼ inch of oil to 400°. Drop about ⅛ cup of batter and cook about 4 minutes or until crisp and golden, turning often. Cooking time will vary based on frying temperature. Drain on paper towels.

For honey-mustard sauce: Heat honey over low heat until soft. Stir in 1 T. Dijon mustard, adding more to taste.

For honey-mustard sauce: Heat honey over low heat until soft. Stir in 1 T. Dijon mustard, adding more to taste.

Serve fritters with honey-mustard dipping sauce. Leftover fritters are best reheated in the oven to keep them crispy.

Serve fritters with honey-mustard dipping sauce. Leftover fritters are best reheated in the oven to keep them crispy.

YIELD: 8 servings.

As a substitute for self-rising flour, place ¾ t. baking powder and ¼ t. salt in a ½ c. measuring cup. Add flour to measure ½ c. For self-rising cornmeal, place 3 t. baking powder and ¼ t. salt in a ½ c. measuring cup. Add cornmeal to measure ½ c.

THESE CHEESE STRAWS break every rule of our modern food system: They take time to make, need to be made by hand and break easily so they don’t transport well. That’s reason enough for us to celebrate the Cheese Straws and let taste triumph over the industrialization of our food. Like a delicate cracker, these Cheese Straws make a beautiful hostess gift when placed in a wide-mouth canning jar (and will at least make it to a party if you hold them between your knees in the car).

1c. flour

1½ t. baking powder

½t. salt

½c. cheddar cheese, shredded

2T. butter

⅓c. milk

1t. canola oil

In a large bowl, stir together flour, baking powder and salt.

In a large bowl, stir together flour, baking powder and salt.

Cut in cheese and butter using a pastry blender until dough looks like coarse cornmeal.

Cut in cheese and butter using a pastry blender until dough looks like coarse cornmeal.

Add milk and mix well. Lightly knead dough into a ball, adding more milk if needed.

Add milk and mix well. Lightly knead dough into a ball, adding more milk if needed.

Roll dough on lightly floured surface to about ⅛-inch thickness, cut into strips 3 inches long and ¼ inch wide.

Roll dough on lightly floured surface to about ⅛-inch thickness, cut into strips 3 inches long and ¼ inch wide.

Bake on a lightly oiled cookie sheet in a 425° oven for 8 to 10 minutes. Watch during last minutes of baking. Straws should be removed from oven just about as they start to brown.

Bake on a lightly oiled cookie sheet in a 425° oven for 8 to 10 minutes. Watch during last minutes of baking. Straws should be removed from oven just about as they start to brown.

YIELD: 6 servings.

Pastured cows in the fields of Green County, Wisconsin, where there are more cows than people.

THE FRENCH HAVE A FLAIR FOR FLAVOR; ingredients are the key and their idea of terroir — or taste of place — helps define farmstead cuisine. Their wines are named by the growing regions; cheeses are named after their small towns. Most beekeepers understand this, knowing full well that their honey will imbue the flavors of what the bees themselves eat. We’ve found the baguette a perfect companion to a meal, a snack or to keep the kids quiet before the entrée arrives. If the baguette dries out, use it in fondue or toast it to make your own bread crumbs or croutons.

2¼ t. dry active yeast (one .25 oz. package)

1c. warm water (warm to the touch)

2T. sugar

2T. canola oil

1½ t. salt

3c. flour

1T. canola oil for the pans and baking sheet

In a large bowl of an electric mixer, dissolve yeast in warm water. Beat in the sugar, oil and salt.

In a large bowl of an electric mixer, dissolve yeast in warm water. Beat in the sugar, oil and salt.

With the dough hook of mixer on low speed or by hand, gradually add in flour to form a soft dough. Mix (or knead by hand) until smooth and elastic, about 6 to 8 minutes. Place in a lightly oiled bowl, turning once to oil the top. Cover and let rise until doubled in size, roughly for 1 hour.

With the dough hook of mixer on low speed or by hand, gradually add in flour to form a soft dough. Mix (or knead by hand) until smooth and elastic, about 6 to 8 minutes. Place in a lightly oiled bowl, turning once to oil the top. Cover and let rise until doubled in size, roughly for 1 hour.

Punch dough down and return to bowl. Cover and let rise for another 30 minutes. Punch dough down.

Punch dough down and return to bowl. Cover and let rise for another 30 minutes. Punch dough down.

Turn out onto a lightly floured surface. Shape into two loaves 12 inches long and 2 inches wide. Place loaves on lightly oiled baking sheet. Cover and let rise until doubled, about 30 minutes.

Turn out onto a lightly floured surface. Shape into two loaves 12 inches long and 2 inches wide. Place loaves on lightly oiled baking sheet. Cover and let rise until doubled, about 30 minutes.

With a sharp knife or kitchen shears, cut diagonal slashes two inches apart across top of loaf.

With a sharp knife or kitchen shears, cut diagonal slashes two inches apart across top of loaf.

Bake at 375° for 30 minutes or until golden brown. Remove from pan and place on a wire rack to cool.

Bake at 375° for 30 minutes or until golden brown. Remove from pan and place on a wire rack to cool.

YIELD: 2 loaves.

|

Sun Oven Cuisine: Cooking Unplugged |

|

“Where do you plug it in?” asked my father-in-law, staring at the boxy thing with aluminum reflectors that focused the sunlight down into the black glass-covered chamber known as the solar Sun Oven, placed on the ground, facing south, in front of our garage.

“Don’t need to,” I replied, as his daughter (Lisa) sent an icy, watch-what-you-say glare my way. Her father was 83, so give him a flippin’ break; he rode to school on a horse-drawn buggy.

“We just point it toward the sun, adjust the tilt so that the sun hits perpendicular to the glass-covered chamber and give it a little time to heat up to 350 degrees,” I continued pleasantly, pointing to the built-in thermometer. “When we’re done, we just fold down the aluminum reflectors and put it away.”

Thus began, in 2008, our adventure in cooking with the sun. We should have invested $150 in one years earlier. Since we use the sun to completely power our homestead, it was about time we did some of our cooking with it.

Sun Oven with bread baking.

As long as it’s at least partially sunny out — and not too windy (the wind will topple over the reflectors) — we use the Sun Oven to bake our bread, simmer our soups, steam our green beans, cook our appetizers and reheat our leftovers. All without a penny of purchased energy. On a bright, warm summer day, the Sun Oven (sunoven.com) does it in just about the same time as in our kitchen oven. The Sun Oven has no moving air, and the oven temperatures rise slowly and evenly, so the foods stay moist, tender and flavorful.

The key to success with a solar oven is, simply, the sun. Point it toward the sun and leave it be. The challenge is remembering that (a) the sun moves across the sky during the day and (b) the sun is higher in sky, almost directly overhead, in the summer and hangs lower in the sky as you head through the winter. Instead of the timer ringing in the house, you’ll need to pass by the solar oven about every 30 minutes to check on cooking progress and refocus the oven on the sun by turning it. A leg in the back of the box lets us adjust the tilt appropriate for the season. Things can occasionally burn in the oven, so you’ll need to keep an eye on it.

You’ll be able to cook the most during the longer days with plentiful sunshine around the summer solstice (June 21); we’ve managed an egg dish in the late morning, fresh bread for a mid-day lunch, and a warm-up of some nibbles in the early evening. But don’t count on much cooking during the winter solstice (December 21) period, especially if you’re in the more northern climates; you’ll be lucky to reheat some leftovers mid-day — if it’s sunny, that is.

In general, most items you’d cook in a kitchen oven can be done in the solar one. For the better part of late spring, summer and early fall, we can achieve an average oven temperature of about 325 degrees, pretty good for most items you may be cooking. There are times, however, when we get the oven just right and the thermometer breaks 400 degrees. Chocolate Chip Zucchini Bread, anyone?

Using the solar oven may, however, create problems if you have a rambunctious dog or an overly curious child. The inside oven chamber does get hot, so it’s wise to keep a couple of hot pads nearby. But cutting down on heat in the indoor kitchen and saving money on electricity or natural gas more than compensates for the inconvenience. That said, we tend to do more cooking outside anyway come summer, so we create a mini-outdoor kitchen area in the gardens. Nothing fancy, just functional, with a small table, a couple of chairs, hot pads and a spoon (for tasting).

You may need to invest in a few small pans that easily fit into the oven. The glass 9 × 13-inch Pyrex baking pans will stick out, thanks to their glass handles, which don’t fit. Any oven-safe pots that fit will work. Some people also use the Sun Oven to dehydrate foods, yet another way you can eat what you grow year-round.

ON OUR FOOD JOURNEY away from the processed, we still had some packaged baggage in the pantry. English muffins, for example — they looked so perfectly browned when toasted and shaped in a way we could never do at home, right? Wrong. The British were eating these at teatime long before supermarkets came along. Not only are English muffins easy to make, they have a fun factor unlike any other bread recipe in this cookbook — you get to grill them, not just bake them. These muffins freeze well; pop the frozen muffins in the refrigerator before you hit the sack, and you’ll wake up to English muffins ready to toast. While these English muffins are terrific, they’re not as holey as those you’ll buy in the store. Does it matter? Not to us — they taste better.

1c. milk

¼c. butter (½ stick)

2T. sugar

2¼t. dry active yeast (one .25 oz. package)

1c. warm water

5c. flour

1t. salt

In a small saucepan, heat milk until it bubbles. Add butter and mix until melted. Remove from heat. Mix in sugar until it dissolves. Let cool until lukewarm.

In a small saucepan, heat milk until it bubbles. Add butter and mix until melted. Remove from heat. Mix in sugar until it dissolves. Let cool until lukewarm.

In a small bowl, dissolve yeast in warm water. Let stand until creamy, about 10 minutes.

In a small bowl, dissolve yeast in warm water. Let stand until creamy, about 10 minutes.

In a mixer bowl, combine milk butter mixture, yeast mixture and 3 cups of the flour. Beat until smooth. Add salt and slowly add rest of flour. Using the dough hook, mix until a soft dough forms, about 6 to 8 minutes.

In a mixer bowl, combine milk butter mixture, yeast mixture and 3 cups of the flour. Beat until smooth. Add salt and slowly add rest of flour. Using the dough hook, mix until a soft dough forms, about 6 to 8 minutes.

Place dough in a lightly oiled bowl. Cover and let rise until doubled, about 1 hour.

Place dough in a lightly oiled bowl. Cover and let rise until doubled, about 1 hour.

Punch dough down. Try not to handle the dough much more after this point in order to keep air bubbles in the dough to help make nooks and crannies. Roll dough to about ½ inch thick. Cut rounds with a wide-mouth Mason jar ring (or something about that shape). Sprinkle a baking sheet with cornmeal and place rounds on top to rise. Dust tops with cornmeal. Cover and let rise about 1 hour.

Punch dough down. Try not to handle the dough much more after this point in order to keep air bubbles in the dough to help make nooks and crannies. Roll dough to about ½ inch thick. Cut rounds with a wide-mouth Mason jar ring (or something about that shape). Sprinkle a baking sheet with cornmeal and place rounds on top to rise. Dust tops with cornmeal. Cover and let rise about 1 hour.

Heat lightly oiled griddle or electric fry pan. Cook muffins about 10 minutes on each side over medium heat or until nicely browned. Then move to oven and bake at 350° for about 10 minutes.

Heat lightly oiled griddle or electric fry pan. Cook muffins about 10 minutes on each side over medium heat or until nicely browned. Then move to oven and bake at 350° for about 10 minutes.

To use, split with a fork (not a knife) to preserve nooks and crannies.

To use, split with a fork (not a knife) to preserve nooks and crannies.

YIELD: 18 English muffins.

POTATOES ARE A BIG SOURCE of our homegrown carbohydrates. By Good Friday every spring, we plant several rows of Red Norland potatoes for an early harvest around the Fourth of July. We also plant Yukon Gold, Satina and sometimes a Russet variety — all of which store exceptionally well if you can keep them cool (around 35 to 45°) and dry. Not just for French fries, hash browns or baked potatoes, our richly flavored spuds make hearty rolls for sandwiches or a basket on the dinner table. Medium-starch spuds, like our Yukon Gold and Satina, work best in this recipe.

7c. flour, divided

½c. sugar

2¼ t. dry active yeast (one .25 oz. package)

1t. salt

2c. milk

1½ c. butter (3 sticks), softened

½c. water

1c. cooked and mashed potatoes (you could also use 1 c. of leftover mashed potatoes)

2eggs

1t. canola oil

In a large bowl of an electric mixer, mix 2 c. flour, sugar, yeast and salt.

In a large bowl of an electric mixer, mix 2 c. flour, sugar, yeast and salt.

In a saucepan over medium heat, heat milk, butter and water to just boiling. Add heated milk mixture to dry ingredients and beat until moistened.

In a saucepan over medium heat, heat milk, butter and water to just boiling. Add heated milk mixture to dry ingredients and beat until moistened.

Add mashed potatoes and eggs. Beat until smooth. Stir in enough remaining flour to form a stiff dough. Do not knead. Put dough in a lightly oiled bowl and turn once to grease top. Cover and refrigerate overnight.

Add mashed potatoes and eggs. Beat until smooth. Stir in enough remaining flour to form a stiff dough. Do not knead. Put dough in a lightly oiled bowl and turn once to grease top. Cover and refrigerate overnight.

Turn out dough onto a lightly floured surface and punch dough down. Divide dough in half. Shape each half-section into 12 balls. Roll each ball into an 8-inch rope and tie it into a knot.

Turn out dough onto a lightly floured surface and punch dough down. Divide dough in half. Shape each half-section into 12 balls. Roll each ball into an 8-inch rope and tie it into a knot.

On a lightly oiled baking sheet, place bread knots two inches apart. Cover and let rise about 2 hours until doubled. Bake at 375° for 25 to 30 minutes or until golden brown. Remove and cool on wire racks.

On a lightly oiled baking sheet, place bread knots two inches apart. Cover and let rise about 2 hours until doubled. Bake at 375° for 25 to 30 minutes or until golden brown. Remove and cool on wire racks.

YIELD: 24 rolls.

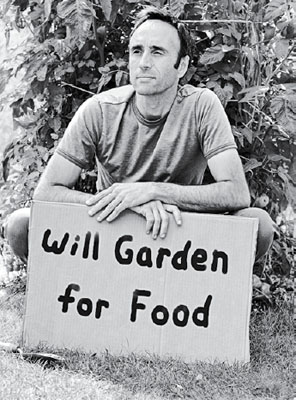

Roger Doiron,

Kitchen Gardeners International,

Scarborough, Maine

Zucchini? Peapod? Cucumber? If we had to give Roger Doiron a vegetable name, it would have to be something with a long vine and lots of fruit. With strong roots in supporting the home gardening revolution, he’s got a wandering, prolific vine side — harvesting ripe, creative opportunities to entice people into rethinking what’s on our plate and how can we grow more of it right outside our back doors. Roger is the founder of Kitchen Gardens International (KGI), a non-profit based in Maine.

Courtesy of Kitchen Gardeners International

“I’m a home gardening evangelist,” Roger says with a modest smile. “We all have good intentions and want to make a difference, but the challenges and problems can seem so large today that it is even more important that we each feel we can contribute something, and growing your own fruits and vegetables provides that opportunity,” explains Roger in a conversation with Lisa. He’s been spending a year abroad with his Belgian-born wife, Jacquie, and their three sons, and running KGI virtually. “Home gardening is an accessible way we can contribute to being part of the solution and enjoy the fruits of our labor.”

“I worked in Europe in the 1990s for Friends of the Earth, and experienced how Europeans strongly connect with their food and how gardening is so much more a part of their daily culture,” reflects Roger on the roots of his gardening passion. “During my travels I saw so many home gardens with every available space used to grow food. That left quite the impression on me. When I got back to the States and walked around my old childhood neighborhood in Maine, I realized how few gardens were left. I had an epiphany that sparked my work today, helping people access tangible and practical information for home gardening.”

He’s filling up the gardening revival tent, that’s for sure. KGI brings together over 20,000 people from 100 countries who are getting their hands dirty through gardening and sharing information and advice prolifically over the Web, answering questions like “Can backyard chickens and a garden peacefully co-exist?” or “How do I organize my seeds?”

“I realized there were a lot of garden clubs already, but I saw a need to start an organization that brought together people specifically dedicated to raising food and who saw their kitchen gardens in a bigger global frame of sustainability,” Roger explains. “My Maine backyard garden is tied to gardens in Australia, India and beyond.”

“The Internet does an enormous job of bringing people together and enabling the spontaneity of messages,” Roger adds. He’s earned a reputation as the MacGyver of new social media, a self-taught guru who creatively taps into innovative communication tools to spread the gardening and healthy food message. From Facebook campaigns aiming to turn the Fourth of July into “Food Independence Day” by encouraging local food picnic fare, to launching a “Real Food” page campaign in reaction to the 1 million fans on the Cheetos Facebook page, Roger packages complex food issues in a way anyone can relate to.

“With the increasing volume of information on the Web, the opportunity to get your message out is still there, but I’ve found how you frame it needs to be something a bit unexpected and new to get people thinking,” advises Roger. The cherry on his social media sundae to date is his successful proposal and petition effort to replant a kitchen garden at the White House. The “Eat the View” campaign garnered over 100,000 signatures, and bushels of international media coverage. Through the use of Facebook and personalizing the gardening message, Roger brought home gardens to the forefront of the White House agenda.

Courtesy of Kitchen Gardeners International

Roger Doiron in his kitchen garden.

“The success of the ‘Eat the View’ campaign reminds me of the power and potential of collective voices and how together we can change how Americans perceive and value food,” Roger explains. “The White House recognized the impact of home gardeners through our efforts. By tearing out part of the White House lawn and planting fruits and vegetables for the President’s family’s meals, this sends a message to the world that we can all contribute to food security.”

Courtesy of Kitchen Gardeners International

AN AVID, ECLECTIC HOME COOK, Roger Doiron dabbles in the international, doing Japanese one night and Moroccan the next. But bread remains a staple at every meal. His recipe for no-knead artisan bread, adapted from his New York Times article, changed our kitchen forever. No bread recipe tops the simplicity and taste of this one. You may react like we did the first time we made it, swearing that this recipe could never work as we stuck the wiggly bowl of dough in the hot oven. Behold, a miracle will appear when you open that lid 30 minutes later.

¼t. active dry yeast

1½ c. warm water

½c. whole wheat flour

2½ c. white flour, plus more for dusting

1½ t. salt

cornmeal or wheat bran for dusting

In a large bowl, dissolve yeast in water. Add the flour and salt, stirring until blended. The dough will be shaggy and sticky. Cover bowl with plastic wrap. Let the dough rest at least 8 hours, preferably 12 to 18 hours, at a warm room temperature (about 70°).

In a large bowl, dissolve yeast in water. Add the flour and salt, stirring until blended. The dough will be shaggy and sticky. Cover bowl with plastic wrap. Let the dough rest at least 8 hours, preferably 12 to 18 hours, at a warm room temperature (about 70°).

The dough is ready when its surface is dotted with bubbles. Lightly flour a work surface and place dough on it. Sprinkle dough with a little more flour and fold it over on itself once or twice. Cover loosely with plastic wrap and let it rest for about 15 minutes.

The dough is ready when its surface is dotted with bubbles. Lightly flour a work surface and place dough on it. Sprinkle dough with a little more flour and fold it over on itself once or twice. Cover loosely with plastic wrap and let it rest for about 15 minutes.

Using just enough flour to keep the dough from sticking to the work surface or to your fingers, gently shape it into a ball. Generously coat a clean dish towel with flour, wheat bran or cornmeal. Put the seam side of the dough down on the towel and dust with more flour, bran or cornmeal. Cover with another towel and let rise for about 1 to 2 hours. When it’s ready, the dough will have doubled in size and will not readily spring back when poked with a finger.

Using just enough flour to keep the dough from sticking to the work surface or to your fingers, gently shape it into a ball. Generously coat a clean dish towel with flour, wheat bran or cornmeal. Put the seam side of the dough down on the towel and dust with more flour, bran or cornmeal. Cover with another towel and let rise for about 1 to 2 hours. When it’s ready, the dough will have doubled in size and will not readily spring back when poked with a finger.

At least 20 minutes before the dough is ready, heat oven to 475°. Put a 6- to 8-quart heavy covered pot (cast iron, enamel, Pyrex or ceramic) in the oven as it heats. When the dough is ready, carefully remove the pot from the oven and lift off the lid. Turn the dough over into the pot, seam side up. The dough will lose its shape a bit in the process, but that’s okay. Give the pan a firm shake or two to help distribute the dough evenly, but don’t worry if it’s not perfect; it will straighten out as it bakes.

At least 20 minutes before the dough is ready, heat oven to 475°. Put a 6- to 8-quart heavy covered pot (cast iron, enamel, Pyrex or ceramic) in the oven as it heats. When the dough is ready, carefully remove the pot from the oven and lift off the lid. Turn the dough over into the pot, seam side up. The dough will lose its shape a bit in the process, but that’s okay. Give the pan a firm shake or two to help distribute the dough evenly, but don’t worry if it’s not perfect; it will straighten out as it bakes.

Cover and bake for 30 minutes. Remove the lid and bake another 15 to 20 minutes, until the loaf is beautifully browned. Remove the bread from the pot and let it cool on a rack for at least 1 hour before slicing.

Cover and bake for 30 minutes. Remove the lid and bake another 15 to 20 minutes, until the loaf is beautifully browned. Remove the bread from the pot and let it cool on a rack for at least 1 hour before slicing.

YIELD: One 1½-pound loaf.

EVERY OCTOBER, Anu visits us. No, the Celtic goddess of abundance, fertility and well-being doesn’t ring the doorbell and walk in. But we sense her presence in the piles of butternut and acorn squash lining our porch. Life feels abundant and prolific, a sense that all will be right with the world because we sit on a pile of winter squash. We cook it, mash it and secretly stick it in just about anything. These rolls are a great way to savor your squash, adding a moist tenderness and deep orange color. They’re perfect for any holiday table.

4½ t. dry active yeast (two .25 oz. packages)

1½ c. warm water

⅓c. sugar

2t. salt

2eggs

1c. winter squash purée

7 to 7½ c. flour

⅔c. butter, melted

2T. butter, softened

1t. canola oil

In a large mixing bowl, mix yeast in water. Let stand 5 minutes.

In a large mixing bowl, mix yeast in water. Let stand 5 minutes.

Beat in sugar, salt, eggs, squash and 3½ c. flour. Beat in melted butter.

Beat in sugar, salt, eggs, squash and 3½ c. flour. Beat in melted butter.

With dough hook of mixer on low speed or by hand, gradually add in enough remaining flour to form a soft dough. Mix or knead until smooth and elastic, about 6 to 8 minutes. Place in a lightly oiled bowl, turning once to oil the top. Cover and refrigerate overnight.

With dough hook of mixer on low speed or by hand, gradually add in enough remaining flour to form a soft dough. Mix or knead until smooth and elastic, about 6 to 8 minutes. Place in a lightly oiled bowl, turning once to oil the top. Cover and refrigerate overnight.

Turn dough out onto a lightly floured surface and punch down. Divide in half and roll each half-section into a 16-inch circle. Spread with two remaining tablespoons softened butter. Cut each circle into 16 wedges, like slices of a pie. Roll up each wedge starting with the wide end and place with pointed end down on lightly oiled baking sheet. Cover and let size about 1 hour until doubled.

Turn dough out onto a lightly floured surface and punch down. Divide in half and roll each half-section into a 16-inch circle. Spread with two remaining tablespoons softened butter. Cut each circle into 16 wedges, like slices of a pie. Roll up each wedge starting with the wide end and place with pointed end down on lightly oiled baking sheet. Cover and let size about 1 hour until doubled.

Bake at 400° for 15 to 20 minutes or until golden brown.

Bake at 400° for 15 to 20 minutes or until golden brown.

YIELD: 32 rolls.

PITAS AND PITA CHIPS are a healthier alternative to store-bought processed crackers and chips laden with preservatives and hard-to-pronounce ingredients usually having something to do with a bad-for-you fat. When we bake pita bread, it can go directly to the next step of making pita chips — our version of a healthier, unprocessed salty snack to crunch on.

2¼ t. dry active yeast (one .25 oz. package)

1¼c. warm water

2t. salt

3c. flour

1t. canola oil

In the large bowl of an electric mixer, mix yeast in warm water. Let stand 5 minutes. Stir in salt and enough flour to make a soft dough.

In the large bowl of an electric mixer, mix yeast in warm water. Let stand 5 minutes. Stir in salt and enough flour to make a soft dough.

With dough hook of mixer on low speed or by hand on a floured surface, knead about 8 minutes until smooth and elastic. Do not let rise.

With dough hook of mixer on low speed or by hand on a floured surface, knead about 8 minutes until smooth and elastic. Do not let rise.

Divide dough into 6 equal pieces. Knead each piece individually for 1 minute.

Divide dough into 6 equal pieces. Knead each piece individually for 1 minute.

Roll each piece into a 5-inch circle. Sprinkle flour on a baking sheet. Place circles on baking sheet and let rise in a warm place until doubled, about 1 hour.

Roll each piece into a 5-inch circle. Sprinkle flour on a baking sheet. Place circles on baking sheet and let rise in a warm place until doubled, about 1 hour.

Flip circles and place upside down on lightly oiled baking sheets. Bake at 500° for 5 to 10 minutes. Remove from baking sheets and cool on wire racks.

Flip circles and place upside down on lightly oiled baking sheets. Bake at 500° for 5 to 10 minutes. Remove from baking sheets and cool on wire racks.

YIELD: 6 pitas.

Cut each pita into 6 wedges.

Cut each pita into 6 wedges.

Take olive oil (about ½ c. for 6 pitas) and add 2 t. salt (garlic salt or seasoning salt works well) and about 2 t. dried herbs like oregano and basil to taste.

Take olive oil (about ½ c. for 6 pitas) and add 2 t. salt (garlic salt or seasoning salt works well) and about 2 t. dried herbs like oregano and basil to taste.

Brush chips on one side with oil mixture using a pastry brush.

Brush chips on one side with oil mixture using a pastry brush.

Place on cookie sheet and bake at 350° until they start to crisp. Watch closely — probably about 10 minutes — to avoid making them too crispy or burnt.

Place on cookie sheet and bake at 350° until they start to crisp. Watch closely — probably about 10 minutes — to avoid making them too crispy or burnt.

Flip chips over, brush again with olive oil mixture, bake for about 5 more minutes until crispy.

Flip chips over, brush again with olive oil mixture, bake for about 5 more minutes until crispy.

When out of oven, brush one more time lightly with olive oil.

When out of oven, brush one more time lightly with olive oil.

YIELD: 36 crunchy, salty chips.