1

A City within a City

Sarah Edelson was a force of nature. For one thing, she was physically quite imposing. Although of medium height, she was broad shouldered and bulky: by more than one account she weighed nearly 250 pounds. But apart from her girth, there was gravitas in her bearing. Her large, hazel eyes flashed when she spoke, and when she did it was in a booming voice that rang with authority. People listened to Sarah, who had been blessed with both a moral compass and a winning smile. A natural leader and a born organizer, she seldom shrank from a fight.

Born Sarah Zimmerman in 1852 somewhere in the Russian Pale of Settlement, she was among the earliest Russian Jews to leave for to New York, arriving in 1868, the same year as her husband-to-be, Joel Edelson. Joel, also Russian-born, became a peddler and they married four years later. In 1876 he naturalized as an American citizen, a process that required little more than proving he had been in the country for at least five years and in New York State for one, and renouncing any residual loyalty he might—improbably—have felt for the czar. Given that the Edelsons had fled a virulently antisemitic Russia, this latter consideration was a low bar. Joel’s naturalization meant that Sarah automatically became a citizen as well, since under U.S. law until 1922 wives were deemed to derive their nationality from that of their husbands.1

Most Russian Jews who came to America had been town-dwellers in the old country. They were not farmers, but largely skilled and unskilled laborers and craftsmen, and so settling in a city like New York made sense because there was employment to be had there. Joel worked as a butcher on New York’s Lower East Side for much of the 1880s and 1890s. By the turn of the century, however, he had given up the meat business and amassed enough capital to open Monroe Palace, a saloon located at 88 Monroe Street.2

The family lived down the street at number 104. By 1900 Sarah had given birth to six children, only four of whom had survived to adulthood. Three were already grown and out of the house, but the requirements of motherhood had never kept her homebound. She kept house, helped out at the bar, and derived additional income by working as a shadchen, a matchmaker, helping young Jewish lonely hearts find one another and, presumably, happiness.

Sarah could be contentious. In 1893, at the wedding of a couple she had united, she had fallen through a trap door accidentally left open by a careless bartender and been seriously injured. She sued the owner of the hall for $20,000 in damages. When a jury awarded her only fifty dollars, she went on to pursue the man into bankruptcy.3

Like most of the half million or so Jewish immigrants on the Lower East Side from the Russian Pale—an area that includes modern-day Belarus, Lithuania, much of Ukraine, and eastern Poland—Sarah was deeply observant. Coming to America in no way signaled an abandonment of Jewish tradition. Attending services at the synagogue on the High Holidays of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur and observing Shabbos, the Jewish Sabbath, were only small signs of their devotion. They lived their religion every hour of every day of their lives. Even their relationship with food was fraught with cultural and religious significance. Inextricably related to their historical identity as Jews, it involved strict obedience to Jewish law.

Like most of her neighbors, Sarah kept a strictly kosher home, which meant, among other things, serving only certain cuts of meat from animals with cloven hoofs that also chewed the cud, slaughtered under strict rabbinical supervision, soaked, salted, and drained of lifeblood. Meat and dairy-based foods were never eaten together—or even within a few hours of each other—due to a broad interpretation of the commandment in Exodus and Deuteronomy never to cook a young goat in its mother’s milk. Observing this commandment meant that even a family without a carpet or a comfortable chair in their home would almost certainly possess two sets of dishes, cookware, and cutlery and a cupboard in which to store them. Nor was seafood ever eaten in her home except for creatures with both fins and scales, the only types allowed by Leviticus and Deuteronomy. This firmly ruled out all kinds of shellfish, among other species. And only specific types of fowl were permitted.

Sarah cut her hair short and wore a sheitl, or a wig, on her head when outside her home in obedience to the Talmudic requirement that Jewish women dress modestly in public. This was thought to de-emphasize their sexual attractiveness to men other than their husbands. She would surely have visited a local mikveh, such as the one in the basement of Norfolk Street’s Beis Hamidrash HaGadol, the city’s leading Eastern European Orthodox shul, or synagogue. There she would immerse herself in a pool of stationary water from a naturally running source before her marriage, after childbirth, and each month, a week after menstruation ended, to render herself ritually pure and able to resume sexual activity.

Six blocks from the Edelsons, in a five-story walk-up at 204 East Broadway, lived fifty-year-old, recently widowed Caroline Schatzberg. Born Chaia Zeisler in Romania, she had married in Bucharest and emigrated to the United States in 1885. Her husband, Simon, a cloak maker, had died in September 1901, leaving her in widow’s weeds with two of her seven children still at home. Sigmund, age twenty, was already working, but six-year-old Dora was still at school. Somewhat more refined than Sarah Edelson, Caroline was also better off financially; she had a live-in, Polish-born servant in her home. White haired but with a youngish face, Caroline had learned English well in her eighteen years in America, and was thoughtful and almost eloquent in the language. There was a quiet strength about her.

1. The Lower East Side. Source: Map of New York and Vicinity. [New York: M. Dripps, 1867]. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, LC-2015591056.

Most housing that immigrants like the Edelsons and the Schatzbergs could afford was communal and offered few amenities. Life in the tenements—New York had some eighty thousand of them in 1900—was a dark, crowded, stifling affair. Several families generally crowded into spaces not designed for multiple occupancy.

Lacking central heating, the occupants relied on wood- or coal-burning stoves for heat, which made the kitchen the only warm room in winter. Summer nights could be unbearable. If the bedbugs didn’t get you, the heat and humidity would. Benzene and kerosene were available to kill the vermin, but many abandoned their mattresses entirely and headed for the tenement roofs to catch whatever breeze might be blowing.

Early buildings, five-story brick structures constructed on twenty-five-foot lots, might house ten to twenty families in flats of two or three rooms, only one or two of which typically faced outside and boasted windows. A ten-by-ten-foot room was considered spacious. Toilets were outside in a tiny backyard or in the basement, one assigned for use by the tenants on each floor. Each had two openings: a large one for adults and a smaller one for children. There was no toilet paper per se; any paper would do, and you had to bring your own. Nor were there any flush mechanisms. “Night soil,” collected periodically, was dumped in the city’s waterways.

If there was running water in the building at all, it would be available via a communal tap in the hallway on each floor. That enabled tenants to wash clothes indoors, first by boiling them, then by scrubbing them on a washboard, and finally by hanging them out to dry on a clothesline suspended between a window and a tall pole in the yard. Scrubbing the common stairways that led to the apartments was a shared responsibility; tenants would take turns doing it.4

After 1879, thanks to the efforts of social reformers, builders of new tenements were required to provide natural light in every room, a problem managed on New York’s narrow lots with interior light wells, shafts that ran from the ground to the roof but were generally too narrow to offer much in the way of fresh air or illumination. Number 88 Monroe, the six-story, brick dwelling between Pike and Pelham Streets where the Edelsons’ saloon was located, had been built with such wells in 1888, though the two-story brick walk-up where they lived was likely an earlier structure that had not.5

Not until 1901 did the New York State Tenement House Act mandate that new buildings be built with larger light shafts, artificial illumination in stairwells, fire escapes, and private toilets in each flat, and that old ones be retrofitted to provide at least one flush toilet for every two families. But that didn’t mean all landlords complied.6

Storefronts occupied the ground floors of most tenements, offering baked goods, meats, groceries, and apparel for sale, and pushcarts laden with other useful merchandise lined Orchard Street, Hester Street, and several other blocks of the Lower East Side. Although the Jewish quarter was big—as the largest concentration of Jews in the world at the time and the most densely populated neighborhood in the nation, far too big for all its occupants to know one another—it was also a remarkably trusting place. Mounds of merchandise and foodstuffs might be stacked on sidewalks while the owner tended to other business, but there was little theft. “The goods outside lie within the reach of all,” the New York Sun observed, “yet the visitor can walk through the ‘ghetto’ and never see man or child take so much as an apple or a plum from the piles placed so temptingly within reach.”7

Russians and Eastern Europeans like the Schatzbergs and the Edelsons were hardly the first Jewish people America had ever seen. Jews had been in America since the seventeenth century, beginning with Sephardim from Holland and the Iberian Peninsula. They had fled poverty and persecution and sought opportunity, and although their numbers were minuscule, it had taken them little time to assimilate and achieve success in America.

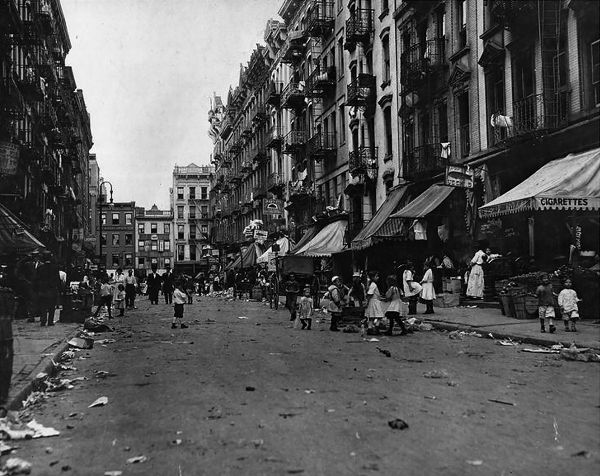

2. Tenements on Orchard Street at the turn of the century. Source: New York Public Library, Image ID: 416563.

Jews from German-speaking lands began to arrive in sizeable numbers in the 1840s, pushed out by persecution and economic hardship. Many of them settled in the Midwest, but a goodly number remained in New York, where they prospered and became Americanized. They, too, had begun life in America on the Lower East Side, but by the turn of the twentieth century many had gravitated uptown. It was they who planted Reform Judaism in America, and once established, they built synagogues like Temple Emanu-El, then an imposing Moorish revival building at Forty-Third Street and Fifth Avenue.

The Edelsons were outliers as far as immigration was concerned; the flow of Jewish arrivals from Russia and Eastern Europe did not gain momentum until the 1880s, when the Schatzbergs, followed by millions of others, crossed the sea. Between two and three million would arrive in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1880 Russians had accounted for only 10 percent of the Jews in America, but by 1906 their numbers had grown substantially to make them about 75 percent of the total.8

Economic, political, and demographic developments had conspired to push these Jews out of Europe. Poverty was a major factor in the decision, often by whole families, to leave lands in which their ancestors had dwelled for generations. Religious persecution played a role also. Official and popular antisemitism on the part of Russians, Poles, and others during the last two decades of the nineteenth century had led to pogroms, violent antisemitic riots in which Jews were murdered and their property was destroyed. Many were expelled from their villages and their occupations and had to find new livelihoods.

America was the favorite destination.

Most of New York’s Russian Jews congregated on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, a quarter the New York Sun considered self-sufficient and self-contained, since everything its people might need could be bought from the local shops, pushcarts, and peddlers, and since it did not contain any thoroughfares vital to the life of the city. “As the famous ghetto of old Frankfurt once was walled in with structures of masonry,” the paper observed, “the ghetto of modern New York is walled in with natural conditions that make it a land so unknown to the mass of the rest of the population that it might as well be in Siberia.”9

As early as 1875 the Sun had taken its readers on a rather disapproving tour of that quarter. The paper saw the Jewish newcomers as a group that “have their own religious institutions, halls of learning and courts of justice.” Years later, the Forward, one of the daily Yiddish newspapers that served the community, referred to the insular neighborhood as a “city within a city,” which was not much of an exaggeration. Many sought to lead lives similar to those they had led in Europe, and make as few compromises as possible with the customs of their adopted land. They had left Russia to escape poverty and persecution, not to change their culture.10

These Jews would have felt entirely out of place in the uptown Reform synagogues of the German Jews. The specter of a pipe organ, or of men with heads uncovered seated together with women during worship looked for all the world like a Christian church to them, and it frankly appalled them. But the condescension was mutual. The uptown Jews saw the newcomers as paupers, beggars, and bumpkins, embarrassing throwbacks who resisted assimilation and thus threatened their own, hard-won but precarious acceptance by non-Jews. The Russians were not welcome in the German Jews’ synagogues or their clubs.

Yiddish was the lingua franca of the East Side ghetto. It was the native tongue of most of the Russian, Polish, and Eastern European Jews, and those who had not spoken it in the old country learned it quickly in America. The Yiddish of the Litvaks—Jews from present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, and northeastern Poland—differed somewhat from that of the Galitzianer Jews from western Ukraine and southeastern Poland, but it was more a matter of accent than dialect. Yiddish’s similarity to German also meant that Jewish newcomers not conversant in English could communicate fairly effectively with earlier arrivals from German-speaking lands. Nuance might be lost, but basic facts were relatively easily understood.

By the turn of the century, newcomers had their choice of several newspapers, each representing a distinct point of view. They mirrored ideologies that had been doing battle for some time in their native lands. The Yidishes Tageblatt and the Morgen Journal offered an Orthodox religious perspective. The Forward was unabashedly socialist. The Freie Arbeiter Shtime was an anarchist paper. For those few who preferred to get their news in English, there was also the New York–based American Hebrew, representing a conservative point of view; the Zionist Jewish Exponent, published in Philadelphia; the American Israelite, a Reform Jewish weekly published in Cincinnati; and the anti-Reform Jewish Messenger, published twice a month in New York. These latter journals, however, were far more popular among assimilated, uptown Jews than Russians or Eastern Europeans.

New York’s Jewish community was too large and diverse for any one umbrella organization to play the role that the kohol—the governing body of a local Jewish community—had played in the towns and villages of Europe. Instead, the East Side was host to a kaleidoscope of associations that ministered to the people’s spiritual, intellectual, and social needs. Apart from the congregations, there were clubs, fraternal lodges, political groups, and trade unions. And most notably, mutual aid societies called landsmanshaftn provided members who hailed from the same European regions with a variety of social services, such as short-term loans and proper burials for the deceased, which were expensive propositions.

Few Russian Jews arrived with much money. Even if they had saved for the trip to America, their funds were usually depleted during an arduous journey by train or wagon, or on foot to Hamburg or Bremen, for example, where they boarded New York–bound ships. There they soon discovered that if the city’s streets were paved at all, it was with cobblestones rather than gold, and too often covered in horse manure.

Men and women with skills found employment easily, often in the growing ready-made garment industry. It was harder for the unskilled; sometimes they were hired fresh off the boat to work in farms or sweatshops, or brought in as scabs to toil in factories whose employees were on strike. Working conditions were typically dreadful. Overcrowded, unhealthy, and unsafe workplaces and, of course, low wages were the rule. Even working fifteen- to eighteen-hour days, most struggled to make ends meet.

Labor unions had preceded the arrival of Russian Jews, and those who entered the trades were welcomed. They represented not only those in the needle trades, but also cigar makers, typesetters, and other skilled workers. The Jewish laborers sometimes formed all-Jewish unions of their own as well, although these frequently did not outlast a strike, whether successful or not. Socialists were particularly active in organizing the new immigrants.11

An East Side husband, if employed, might bring home something like two dollars a day and would typically turn the entire sum over to his wife to manage the household. She might supplement it with proceeds from peddling or taking in washing or sewing; from sending a daughter to work in a sweatshop; or, commonly, from rent collected from a boarder, who would pay about fifty cents a week for a bed in a corner, a peg on which to hang his clothing, and maybe a cup of coffee in the morning.

Just over thirty cents a day would go to rent, which ran about ten dollars per month for an average flat. Food for a family of six would require fifty or sixty cents a day. Potatoes cost two cents a pound in 1902; beets fetched seven. A pound of onions cost a nickel, the same as a head of cabbage. A loaf of pumpernickel bread went for three cents; carp, a favorite, along with pike, for making gefilte fish—poached, minced fish balls—sold for a nickel a pound.

Immigrant Jewish women had more latitude than they had had in Europe, where traditions were deeply rooted and social pressure made convention hard to ignore. It was up to them to decide how to balance tradition with the realities of life in a Christian country, and many felt the tension inherent in the position they occupied between the two worlds. Shopping for and preparing food generally fell into their bailiwick, and they were responsible for decision making in this important area.

Some, seduced by lower prices or convenience, and less susceptible to the judgments of neighbors in a small community, became lax in their piety, and in their observance of the dietary laws in particular. They might be tempted by nonkosher beef, though few likely went so far as to embrace pork. But for most, and even many who were desperately poor, certain corners simply could not be cut. They considered themselves bound by all the commandments in the Hebrew Bible, of which they counted 613. Fully twenty-six of them related to diet. By contrast, Reform Jews probably seemed to them to obey only those biblical directives that suited them.

Many Russian Jews in New York in 1902 were not only strict in their adherence to the dietary laws; they observed all the holidays and fast days on the Jewish calendar. They did no work on Shabbos if it could be avoided, nor did they travel or light fire on that day. Preparation for Shabbos began on Friday, or even Thursday. It was the busiest time of the week. Challah, a braided, glazed egg bread traditionally eaten on the Sabbath, had to be baked or purchased for a few pennies a loaf.

Cholent also made frequent appearances on Shabbos lunch tables. A stew consisting of some combination of meat, potatoes, onions, beans, barley, and whatever else was on hand, it was actually a solution to the conundrum posed by the prohibition against lighting a fire on the Sabbath on one hand and the desirability of eating a hot meal on the day of rest on the other. Before sundown on Friday, the ingredients would be assembled and boiled, and the pot then either brought to a local bakery and inserted into an oven still hot from baking challah, or placed on a metal plate on the stovetop at home and kept warm there. This was crockpot cooking, 1900s-style. The dish would slow-cook over a low flame until the next day, when all the flavors had commingled into a tasty stew.

Russian and Eastern European Jewish society was both patriarchal and chauvinistic. With few exceptions, roles were assigned according to gender. Educating sons was mandatory; with daughters, it was optional. Most women had domain over their kitchens, but were not expected to play a role in public life, and most did not. It was their husbands who were the principal breadwinners, who worked outside of the home, and who joined unions and political and mutual aid associations. They were the titular heads of the household.

But anyone who took that to mean that the women were homebound, shrinking violets who deferred meekly to the authority of their spouses didn’t know much about Jewish women, and surely hadn’t met Sarah Edelson or Caroline Schatzberg. Women like them were far more influential than their husbands in important decisions that affected their families. They often shared responsibility for managing family businesses, and many were born organizers, extremely hard driving when it came to protecting and caring for their loved ones.

If life in America presented immigrant Jewish women with new challenges, it also afforded them new opportunities for involvement in the public sphere that had not been easily attainable in Europe. They were still primarily mothers and wives, but many worked at home or helped run family enterprises, and these had contact with the larger community. Many of their daughters had begun to work outside the home in tenement sweatshops or in factories. Labor unions opened their ranks to them, as did political organizations peddling ideologies from socialism to anarchism to Zionism. Americanization was a slow process that affected some more rapidly than others, but it offered numerous possibilities for growth and change, and for life beyond the four walls of depressing tenement apartments.

The big news in the spring of 1902, with the Passover holiday just around the corner, was that the price of kosher meat had skyrocketed. A pound of flanken, or short ribs, which had cost twelve cents only a few months earlier, had risen a whopping 50 percent and was now selling for eighteen cents. Sarah and Caroline and other Lower East Side balebostes—housewives—had been feeling the pinch for months, but 1902 saw a sudden, most unwelcome spike. Eighteen cents a pound, for many families struggling to make ends meet, was simply beyond reach.

Since eating cheaper, nonkosher meat was out of the question, choices were few. What would happen if kosher meat became unaffordable, which was where it seemed to be heading, was everybody’s worry. And anybody’s guess.