3

The Conscience of an Orthodox Jew Is Absolute

The pressure the Beef Trust put on cattle prices, coupled with the efficiencies of its giant packing plants and the rebates it extorted from the railroads, meant that beef butchered in Chicago could be sold more cheaply in Manhattan than that killed locally. Western-dressed beef thus came to fill most of New York’s needs quite handily. Carcasses were delivered to storage houses in Manhattan and New Jersey, where they awaited sale and delivery to city butchers. By 1902 nearly two-thirds of the beef sold in New York had been slaughtered before it arrived.

The market for that last third had three important components. The first consisted of high-end hotels like the Waldorf, the Holland House, and the Hotel Manhattan, as well as the city’s finer dining establishments, where quality and freshness trumped price. Western-dressed beef might sit in the cooler of a midwestern slaughterhouse for three or four days before transport. It took two or three more days to get to the East Coast. Even then it might hang in a storage locker in Weehawken or Jersey City for a week or more before being ferried across the Hudson River for final sale. And some of it was treated with boric acid, a preservative, to make it appear fresher than it actually was. It was far easier to guarantee the freshness of “city-dressed beef,” as New Yorkers called the locally killed variety. And that’s what mattered most to the upper class diners at the Waldorf, for whom an extra two to four cents a pound for choice cuts was not a consideration.1

The second market for such beef was the international one. The New York Central Railroad maintained stockyards at Sixtieth Street and the Hudson River for livestock bound for Europe, principally England. Some foreign-bound cattle, shipped on the hoof from the Midwest, came from holding pens in New Jersey. It would be loaded onto ships for Liverpool, London, and Hull and ports on the continent.

The third and largest component of the market for cattle brought to New York alive was the Jewish community.

One of the many rules governing kosher meat, apart from the species of the animal and the method of slaughter permitted, mandated that no more than seventy-two hours elapse between the killing of an animal and the kashering—soaking and salting—of its flesh, a final purification procedure generally performed in the home during this era, designed to drain it of all vestiges of blood. This was because after that interval, blood becomes too congealed to extract.

For this reason, the Orthodox—the majority of New York’s estimated 585,000 Jews in 1902—could not avail themselves of western-dressed beef. Even if it were properly slaughtered in Chicago by qualified, observant Jews, it simply took too long to get to their kitchens for New Yorkers to render it kosher. A secondary factor was that keeping track of meat that changed hands many times over a long distance was difficult, and the risk of forbidden meat being substituted for the kosher variety, whether accidentally or deliberately, was substantial. Locally slaughtered kosher meat had a far shorter chain of custody between supplier and consumer, and was thus more likely to be the genuine article.2

The lion’s share of the animals that would become city-dressed beef, whether for the kosher market or otherwise, were purchased in Chicago or Kansas City, brought in by rail, and delivered to the Jersey stockyards. Because the journey took a toll on the animals, they were permitted a day of rest before being inspected by government officials and sold at auction. Buyers for the wholesalers would journey from New York to examine and bid on them while they were still in the pens. Those chosen would be tagged and driven aboard double-decker barges and unloaded on Manhattan’s or Brooklyn’s shores.3

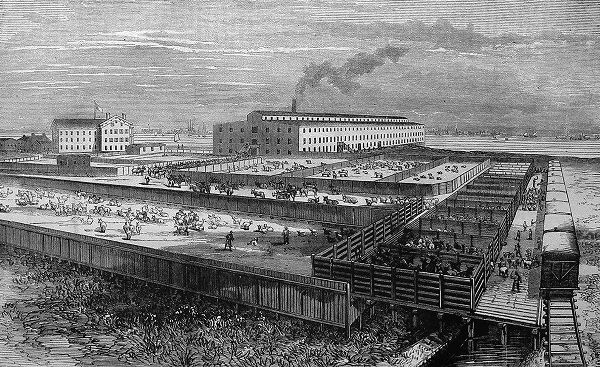

4. The Communipaw Stockyards at Jersey City, New Jersey. Source: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 17, 1866.

The next stop for most of them was one of Manhattan’s East River slaughterhouses. The two dominant concerns were located on First Avenue between East Forty-Third and East Forty-Sixth Street. Schwarzschild & Sulzberger occupied two city blocks and United Dressed Beef Company was immediately south of it. Both establishments backed up to the river, facilitating the transfer of livestock from the barges. A third wholesaler, Joseph Stern & Sons, was located at Thirty-Ninth Street on the Hudson. All of these engaged in both regular and kosher slaughter, and all were owned and operated by Jews of German extraction.

At United Dressed Beef, about three thousand steers were killed each week, fully 80 percent of them in the kosher manner. At Schwarzschild & Sulzberger, the number was thirty-five hundred per week, but there only about a third of the cattle were slaughtered according to Jewish law.4

Ritual slaughter could be undertaken only by a shoychet, a pious and usually burly Jewish butcher with a steady hand. He would have learned the codes of Jewish law pertaining to kosher meat and apprenticed as well. In the old country he would have been accredited and appointed by the chief rabbi of a community; in New York, most any Orthodox rabbi might do. In Europe, he would work under the supervision of a mashgiach, a rabbinical inspector, who represented the community rabbi and was vested with broad responsibilities over all types of food, not just meat. In America, however, the shoychet might work independently and be paid a flat salary by the slaughterhouse. To avoid corruption, he was not to profit from the volume of cattle he killed.5

A non-Jewish slaughterer might strike a steer on its head with an axe to stun it before dispatching it, but such a method was forbidden to a shoychet for two reasons. First, because an animal had to be without blemish, broken bones, or wounds to be kosher. And second, because a single stroke of a sharp knife was believed to be the quickest way to render a beast senseless, and therefore the most humane means of slaughter available. It was also considered a more hygienic method.

5. A turn-of-the-century postcard view of Manhattan’s East River slaughterhouses. Schwarzschild & Sulzberger occupied two city blocks and United Dressed Beef Company shared the block immediately to the south. The United Nations currently stands on this land. Courtesy of Curt Gathje.

Of vital importance to the shoychet’s craft, therefore, was a razor-sharp, blunt-nosed steel knife about two feet in length. Once an animal had been selected—and the shoychet was bound to reject any that appeared unhealthy—ropes looped around both horns and the legs and run through a ring on the wall or the floor would be tightened slowly to coax it down until its head and shoulder touched the floor. A muzzle would then be placed over its snout and its neck would be bent sideways. In the meantime, the shoychet would run his fingernail over the edge of the knife to ensure there were no notches or rough patches on the blade, which might tear the flesh and add to the animal’s suffering. Any imperfections would have to be ground out on a sharpening stone before he could proceed.

Once satisfied the blade was razor sharp and completely smooth, he would splash water across the animal’s throat, recite a Hebrew blessing and then slash its windpipe, cutting the trachea and esophagus in a single stroke. Any interruption in this motion would immediately render the animal treyf, or unacceptable. The cut would cause both the carotid artery and the jugular vein to bleed profusely, sending the animal immediately into shock. The rapid loss of blood was understood to cause the beast to lose consciousness within two or three seconds.

After the animal had bled out, it would be hung from a hook for examination of its entrails. A second, shorter knife was used for disemboweling. If posthumous inspection of the heart, lungs, liver, or other vital organs revealed any foreign bodies or any hint of disease, the animal would be rejected and the carcass diverted to be sold as regular city-dressed beef or, in extreme cases, presumably discarded. The lungs were examined especially carefully for any sort of pleural disease, and in case of doubt were removed, bathed in water, and inflated by mouth to reveal any subtle abnormalities. If they held air, the animal would be considered kosher.

Only about 65 percent of the cattle killed passed this internal inspection. Of those that did, only about a third of the meat on their carcasses—the forequarters as far as the thirteenth bone of the rib cage, including the breast, shoulder, and the first four ribs—might be certified as kosher. The hindquarters, although technically edible, were typically branded as treyf.

This rule proceeded from chapter 32 of Genesis, in which Jacob wrestles with an angel of God and suffers damage to his hip and thigh, interpreted as his sciatic nerve. Jewish law insisted that kosher meat not contain certain blood vessels or nerves, which had to be plucked out by hand. It was difficult enough to do this to the forequarters of the animal, but especially tedious—and not cost-effective in America, at least—to do it to the rear parts, which contained more tough, fibrous tissue and multiple small veins. Not for New York’s Orthodox Jews were the porterhouse steaks or the tenderloins. In principle, even this part of the steer could be made kosher with enough effort, and sometimes had been in Europe, but in America it was far more expedient to sell it to non-Jewish consumers as regular, city-dressed beef.

The entire process was thus one of winnowing out so-called unclean meat. Obviously unhealthy animals were excluded at the start. Fully 35 percent of those slaughtered by shoychtim were classified as unkosher. Only the forequarters of the 65 percent that passed inspection could qualify, and even that meat was reduced in weight by as much as a fifth by the process of draining blood and removing bones, sinews, and forbidden fats. What this meant, in practice, was that nearly 80 percent of the meat of those animals slaughtered according to Jewish law had to be sold to gentiles, nonobservant Jews, or nonkosher sausage factories, or else discarded.

Naturally, this made kosher beef more expensive than other city-dressed beef, which itself cost a penny a pound (or an average of seven to eight dollars per carcass) more than Chicago-killed beef because it was shipped on the hoof. Kosher slaughter added another penny a pound to defray the salaries of the slaughterers and supervisors, who took home anywhere from eighteen to twenty-five dollars per week ($530 to $730 in today’s currency). But this did not dissuade observant Jewish consumers, who were compelled by their religious beliefs to buy it if they wanted meat on the table. Nor did it deter a smaller number of non-Jews who preferred it because they believed it cleaner and more wholesome than other available meat.6

After a carcass was declared kosher, a seal bearing the signature of the shoychet and the date of slaughter was affixed to it. This served as a guarantee to local butchers that the meat on it was properly killed, and a signal as to how much time had passed since then. Then it would be shunted off into a cooler and hung, neck down, and stored with others at thirty-six degrees Fahrenheit. Later in the day, the forequarters would be severed from the rest of the carcass and prepared for sale and delivery to the kosher markets.

The next link in the chain was the retail kosher butchers. In 1902 there were an estimated six hundred of them in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. Typically, they would tend to their customers in the morning and visit the slaughterhouse coolers early in the afternoon to select their purchases, though the abattoirs also sent salesmen to visit those who couldn’t spare the time to make the trip. Different grades of meat fetched different prices. If more than one butcher set his sights on a particular animal, a bidding war might ensue.7

Given the time pressure imposed by the fixed interval between slaughter and final preparation, the slaughterhouses’ salesmen had a strong incentive to sell all kosher beef on the day the animal was killed. Meat left over from the day before was still marketable, but older carcasses had to be sold at a discount of a few cents a pound.

The industry was also prey to speculators, who generally got to the wholesalers earlier than the butchers and bought up the choice carcasses. Retail butchers, finding the best grades already sold, were then faced with the choice of buying poorer quality meat from the wholesalers or paying a few cents a pound more to speculators, whom they resented very much.

Once a sale was made, a tag noting the name and address of the customer was affixed to the carcass and notice of the sale would be sent to the credit department for approval. Butchers, often cash-poor, were granted a two- to three-day grace period to enable them to use proceeds from the resale of meat to reimburse the slaughterhouse, but only if they were in good standing. If not, it was strictly cash on the barrel. Those retailers with their own trucks might haul away their purchases; meat would be delivered to others by the wholesalers’ or speculators’ wagons, often in the wee hours when the stores were closed. This required a measure of trust, because it necessitated letting the deliveryman know where the key to the shop was kept. He would be permitted to enter the store and place the cargo in the butcher’s icebox.8

Most killing for the kosher trade took place on Fridays and Mondays. Because the shoychtim couldn’t work on the Jewish Sabbath and the retail kosher markets were closed during the daytime on Saturdays for religious reasons and all day on Sundays because of state law, Friday was a high-volume day. Friday-slaughtered meat was delivered after sundown on Saturday, when demand among Jewish households was high for late Saturday and Sunday consumption. Retailers took care not to order too much of it, however, because if it was not sold by Monday night the window between slaughter and kashering would have closed. Hence Mondays marked another big slaughter day for the kosher market.

The task of the retail butchers was to extract bone and gristle from the meat, and of course to chop it into the various cuts that the forequarters of the beast provided. Most of those in New York in 1902 were located on the Lower East Side, often several to a block. Some sold both kosher and unkosher meat, and if they did, had to be trusted to keep them separate. If not, they would not be able to build lasting relationships with local Jewish women, who made up most of their customers and who, if they kept kosher homes, would not dream of serving treyf meat to their families.

Poultry, more expensive than beef, traveled a different route. Most of that consumed in New York was raised within a radius of a couple of hundred miles from the city. Wholesalers brought it by truck into town, where it was slaughtered by shoychtim and sold by local butchers. Because of the popularity of chicken as a Sabbath meal, the biggest business day of the week for kosher poultry was Thursday. The wholesaler would endeavor to get it to the retail butcher while the body was still warm, as the women of the Lower East Side much preferred to purchase just-killed fowl. In 1902 kosher chicken fetched anywhere from eighteen to twenty-five cents a pound.9

No particular rule governed the killing of fish; there was just an absolute restriction against eating any aquatic creature without both fins and scales. The shops and pushcarts on Hester Street sold fish at anywhere between eighteen and thirty cents a pound, with pike commanding the highest prices. Haggling with the vendors was de rigueur.10

“The conscience of an orthodox Jew is absolute when it comes to kosher meat,” a First Avenue butcher told the New York Tribune. By this he meant that observant Jews would not accept any short cuts in this area. Jewish housewives typically chose butchers who were observant themselves; no one would buy from one who did not follow the religious laws in his personal life. He would be expected to belong to a synagogue, attend services regularly, and, of course, keep a strictly kosher home.11

Most of New York’s kosher butcher shops were small affairs that required relatively modest investment. Expenses included rent, wages (a typical butcher needed an assistant), utilities, ice, packaging materials, delivery charges, and, of course, wholesale meat and poultry. A chopping block and a few benches were the only furniture necessary. Equipment included knives, cleavers, and saws; a cash register, a scale, a grinder, paper for wrapping purchases; and an icebox, usually located in the rear of the store. Poultry, cuts of beef, and organs would often be suspended from hooks and displayed in a shop window. The benches were used for extracting forbidden parts and trimming meat to the customer’s specifications; the block was necessary for chopping thicker, bone-in cuts. A typical establishment was long on functionality and short on ambience.12

6. A typical turn-of-the-century New York kosher butcher shop. Pictured behind the counter are butchers Abraham (left) and Max Farber. Source: Old NYC Photos.

Lower East Side women typically patronized butcher shops within walking distance of their homes, often on the same block. They bought meat frequently and in small quantities; economies of scale from larger purchases were out of reach for most, not only because of a shortage of cash, but also a lack of iceboxes. The bond between the butcher and the housewife was an important one: there had to be trust, and there often had to be credit as well. Good customers known to the shopkeeper could maintain accounts and pay for purchases later. Uncollected debts put pressure on butchers’ balance sheets, but extending credit was absolutely necessary for many to stay in business, because so many of their customers lived payday to payday.

One more hurdle had to be cleared before meat was considered fit to eat. When a Jewish housewife like Sarah Edelson bought a rib roast or a piece of poultry from her butcher, she had to kasher the meat by soaking it in water for half an hour and then sprinkling it with coarse salt—known today as “kosher salt”—to rid it of impurities and residual blood. Then, and only then, could she cook it and serve it to her family.

The rules governing kosher meat were matters of religious law, and the Orthodox Jews of the Lower East Side were served by providers who were themselves observant people.

But this, alas, did not mean that corners were never cut.