4

Each One Is an Authority unto Himself

If this system of devout Hebrews in New York City strictly discharging their duty to their fellow Jews to produce and sell kosher meat sounds like a well-oiled machine programmed to do God’s work, it was actually anything but.

As early as 1863 an anonymous letter in the Jewish Messenger, a weekly Orthodox newspaper, had decried the lack of supervision over the shoychtim. The system was corrupt, the author asserted, and as a result, many Jews who thought they were obeying the dietary laws were, in fact, not eating kosher meat at all.

At the time, there were a dozen or so Jewish slaughterhouses in the city and the shoychtim, the paper complained, “are neither authorized by the congregations nor by the ministers.” Although some were certified in Europe before they emigrated, they were never re-examined to determine whether they remained competent. The only judgment of their proficiency was made by those in the meat business who paid them, people with a vested interest in keeping the price of meat high and who didn’t ask too many questions. It was to their benefit for the slaughterers to bend the rules because kosher meat fetched higher prices.

The solution, the writer asserted, lay in cooperation among the Orthodox congregations, which were urged to band together and select two or three local rabbis to supervise the slaughterers on a rotating basis. If paid by their congregations and not by the butchers or the slaughterhouses, they would have only the interests of their fellow Jews at heart, and would lack incentive to look the other way if they detected transgressions.1

Nothing happened, however, and not much had changed sixteen years later when the Messenger itself called for a solution. If anything, the situation had gotten worse. “Uncleanliness, over-charges, incapacity, roguery have combined to render suspicious nearly every butcher who hangs out the sign ‘kosher,’” it complained. “Our own self-respect and sense of duty should lead us to unite in a movement to uphold the purity and Jewish character of our households.”2

But self-respect and sense of duty were in short supply. Hungarian-born Rabbi Moses Weinberger, in a dark portrayal of Jewish life in New York written for his fellow Orthodox Jews in 1887, had a lot to say about problems with the local kosher meat supply. Since the shoychtim were engaged by the slaughterhouses, there was no religious authority to ensure quality control over who was hired, as there might have been had the synagogues engaged the men directly. Some were reputable slaughterers who had been vetted in Europe, but others had been removed from office there and decided to start anew in America, where their pasts would not follow them. Still others were simply poorly schooled in ritual law. And in America, nobody supervised them.

Then, too, the relationship between the slaughterers and the retail butchers was often fraught. “Not a day goes by without screams and quarrels between shoychtim and butchers,” Weinberger wrote. “Each side composes and spreads libelous documents about the other, stinging and battling, while Israel looks on, its sight failing, helpless.”

Weinberger was equally critical of retail butchers, many of whom he was certain were corrupt. “There are those who are not embarrassed to take improperly slaughtered meat and to sell it publicly to innocent people, notwithstanding the fact that their stores are anointed in huge, gilded letters with the words ‘KOSHER MEAT,’” he wrote. And some split the difference, selling properly killed flanken but at the same time passing unkosher organ meat off as kosher.3

It wasn’t as if kosher meat production in the old country had been immune to fraud or corruption, but there misbehavior had been more easily controlled. Civil authorities in many Eastern European countries had delegated legal responsibility for Jewish affairs to the kohol, or governing body, which was therefore in a position to penalize transgressions with fines, excommunication, and even corporal punishment.4

When a kohol paid a slaughterer a fixed salary that did not fluctuate with the kosher meat yield from the animals he killed, and when it forbade him from participating financially in the meat trade, his incentive for corruption was diminished, if not removed entirely. And when it possessed the authority to punish him, he thought twice about skirting the rules.5

But the kohol system had never taken root in New York. The city was simply too big, and its Jewish community too numerous and too balkanized. The system that had served smaller Jewish communities in Europe well would not do in Manhattan. But to several Orthodox congregations on the Lower East Side, that did not mean that a chief rabbi could not bring order to the out-of-control slaughtering business. Jews in Britain had appointed such a man in the 1840s, and the idea had been raised in America before. In mid-1879 it had looked as if it might come to fruition when several congregations raised funds and recruited a noted Eastern European talmudist, but he had declined and the effort had come to naught.6

Another attempt was made in 1887 after the death of the rabbi of the Beis Hamidrash HaGadol, the Orthodox shul that had been established in 1852. That congregation took the lead in founding an Association of American Orthodox Hebrew Congregations that consisted of itself and seventeen other Russian and Eastern European synagogues on the East Side. Money was pledged and a new search was organized.

The perceived need for a chief rabbi was actually about much more than the chaos reigning in kosher slaughter. Orthodox Judaism, Eastern European style, was not standing up as well to the pressures of life in America as many wished, and some of its leaders were feeling besieged. The children of the Orthodox were becoming Americanized and beginning to eschew many traditions. The Reform Judaism favored by many uptown German Jews offered an alternative, if alarming, model. So, for some, did secularism.

Even within the Orthodox community there was little discipline. Tiny congregations—shtieblach—sprang up and then dissolved into factions. Many were lay led and could not afford rabbis, who were desirable, but not necessary, for formal Jewish worship, where a quorum of ten men sufficed. And even where there were rabbis, few commanded the respect enjoyed by those in the old country. Because Jewish law was not binding in America, their decisions could safely be ignored by any who chose not to recognize their authority. Some were unqualified for their positions. There were even occasional charlatans among them.7

A new chief rabbi might unify at least the “downtown” Jews, represent them to the larger community, oversee Jewish education for the young and preside over a beis din, or religious court, to adjudicate disagreements. But it was clear his principal task would be to bring order to the system of kashrus—dietary laws—and this was written into his job description: “His mission would be to remove the stumbling blocks from before our people and to unite the hearts of our brethren, the house of Israel, to serve God with one heart and soul, and to supervise with an open eye the shoychtim and all other matters of holiness to the House of Israel, which to our deep sorrow are not observed nor respected, because there is no authority nor guide revered and accepted by the whole community, and each one is an authority unto himself.”8

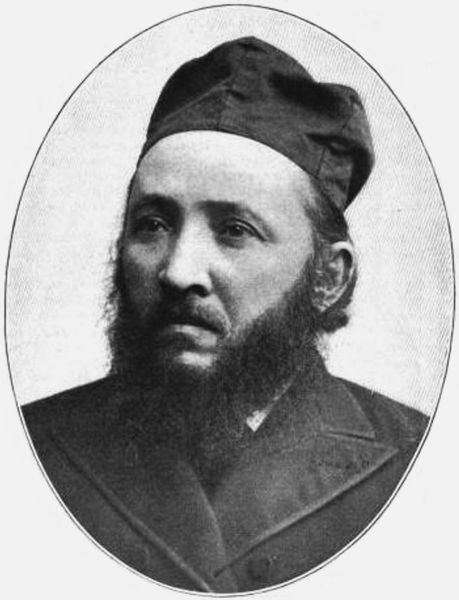

In 1887 the Association of American Orthodox Hebrew Congregations recruited a European luminary to assume the newly created position of Chief Rabbi of New York. Jacob Joseph of Vilna (Vilnius) was a well-regarded talmudic scholar, but one who had amassed substantial debt. He was offered a six-year term at the princely salary of $2,500 per year—about $66,000 in today’s currency—plus a large apartment and a travel allowance for himself and his family. Joseph was amenable if he were granted a signing bonus that would permit him to settle his obligations before he left Europe.9

There was much excitement on the Lower East Side on July 7, 1888, when the SS Aller docked at Hoboken, New Jersey, with forty-eight-year-old Rabbi Joseph on board. But it was Shabbos, and so the reception committee from the association, in their best black suits and tall silk hats, had to bide their time until sundown before the learned man would disembark. They themselves had arrived from Manhattan before dusk on Friday to avoid forbidden travel on the Sabbath.

At nearly 10:00 p.m., well after the sun had safely set, a compact, bright-eyed man with a full beard and a winning smile appeared alone. He had left his family behind until he was certain his decision to come was a sound one. The streets were lined with people who had assembled to welcome him as he was escorted to a hotel for prayers and subsequently taken across the river to 179 Henry Street in New York, where an apartment had been rented for him at a cost of $1,300 per year ($35,000 today). Another $4,000 ($106,000 today) had been spent fitting it out for him and his family.10

It was an auspicious beginning to what would turn out to be a very sad story.

Even before he arrived, it was clear Rabbi Joseph would not speak to, or for, all of New York’s Jews. Most uptown Jews saw his appointment as beneficial to their downtown brethren, especially if he could rationalize the kosher food supply. But for the most part they did not intend to accept his authority themselves. Adolph L. Sanger, one of the officers of Temple Emanu-El, the flagship Fifth Avenue Reform temple, told the New York Herald that “the question as to whether certain congregations put themselves under Rabbi Joseph’s control lies with themselves and is entirely voluntary. It is not at all likely that any of the uptown congregations will recognize him at all, although possibly some of the more orthodox may.”11

7. Rabbi Jacob Joseph, the chief rabbi of New York—or some of it.

Even many downtown Jews had their doubts. An unnamed Russian Jew who had lived in America for six years put it this way: “No matter how great the respect and admiration commanded by Rabbi Joseph is, his power scarcely extends beyond the older element of the Hebrew community.”12

Nor could Joseph count on support even from those downtown Orthodox congregations that had not joined the association that hired him. As one leading member of such a shul told the New York Sun, “I am opposed to the enterprise, not because I am averse to having a learned rabbi and an able preacher . . . but because the power vested in the new rabbi extends far beyond mere preaching and expounding the laws about religion. The plan to bring all the Jewish butchers under his jurisdiction . . . won’t work here. Our butchers and their customers are aroused by the intended reform, and I fear it will give rise to serious conflict.”13

It was a prescient remark.

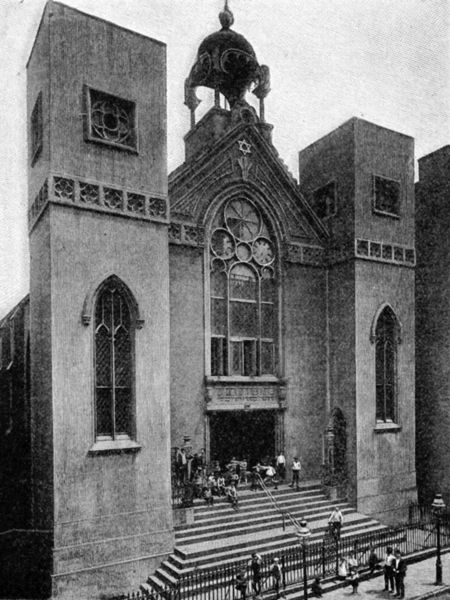

Rabbi Joseph’s first address to his new flock came on July 21 at the Beis Hamidrash HaGadol on Norfolk Street. Its sanctuary could seat a thousand, but twice that number showed up, necessitating the presence of twenty-five policemen to close the street and let no more worshipers in. To the devout Jews assembled in the pews, galleries, and aisles, the rabbi spoke in Yiddish, directing some of his remarks to the women present.

To you, fair daughters and good mothers of our race, I appeal to keep this house inviolate. Whatever may be your influence on mundane affairs, I speak to you on behalf of the religion based exclusively on domestic virtue, on sublime truth and on the sanctity of family relations.

You who have upheld the religion of your fathers with more strictness even than your husbands and sons and brothers, I beseech to aid, encourage and induce those male members of your family, to . . . keep intact the structure known as the House of Israel. That is your mission. Lift them up then also to the higher spheres of the religion which have kept forever the homes of the Israelites sacred. And may God bless you for such undertaking.14

8. Beis Hamidrash HaGadol Synagogue on Norfolk Street, early 1900s. Source: Wikipedia.

Singling out the women was no accident. Joseph knew that in most Jewish households, responsibility for observing religious laws fell on the wives and mothers. Implied, but not stated overtly, was their sacred responsibility to keep kosher homes.

In September, he visited some slaughterhouses to ascertain whether the knives being used to kill cattle passed muster. His first serious effort to assert his authority, however, was not in beef, but poultry. Late that month, he sent two hand-picked mashgichim—supervisors—to Fleischhauer’s slaughterhouse on East Seventy-Sixth Street to determine whether fowl was being killed properly there. Charles Wolf, the shoychet, did not take kindly to unannounced supervision and ordered the men off the premises. But not only did they refuse to leave; they broke the leg of each chicken that did not appear to them to have been slaughtered correctly. Wolf had them arrested for disorderly conduct and they were taken to the Essex Market Police Court, where the judge eventually discharged them.15

This may have been all the reconnaissance Rabbi Joseph needed to hatch his first scheme, which was designed to combat the problem of ersatz kosher poultry being sold as the real thing. As he wrote to the association that had hired him, now twenty-three congregations strong:

We have appointed men, learned and skilled in the profession, to supervise the work of the slaughterers, that it be done in accordance with our sacred law. But this is not sufficient, for we are unable to inquire into the trustworthiness of all the butchers selling kosher meat. We have authorized our own butchers to put our seal upon the meat that is prepared under the supervision of our men. Thus the pious, who will be guided by our teachings, may be perfectly assured that the meat which they buy is kosher beyond a doubt if it is stamped with our seal, and that we do not hold ourselves responsible for the perfect fitness of meat that is not so stamped.

The seal, called a plombe, was a small, lead tag that could be attached to fowl or meat that testified to the fact that it had been slaughtered under the supervision of one of Joseph’s mashgichim and that indicated the date of slaughter. But the plombe scheme would have to be financed. Rabbi Joseph received a salary from the association’s constituent congregations in order to avoid any conflict of interest, but his coterie of mashgichim would also need to be paid if the new system were to be self-sustaining.

The association’s solution was to charge buyers an extra penny for each bird with a plombe attached to its leg. That way, those who benefited from the new system would finance it. Joseph objected to this; he believed the plombe would aid the entire community and that the association should foot the bill. He eventually agreed to charge fowl purchasers for a plombe, but he drew the line at charging beef buyers for one, because beef was a staple of poorer Jews, and chicken, which was more expensive, was more likely to be bought by the affluent.16

It all sounded logical, but there were vested interests at stake, and it didn’t take long for the long knives to be drawn. The rabbi’s instincts were correct. Many butchers objected to the new rules, and Jewish housewives resented the extra charge. Brickbats came from rabbis who had overseen the meat business before Joseph showed up and were now disenfranchised. And even those not directly affected—secular socialist Jews, and some uptown German Jews who didn’t keep kosher homes—criticized the new arrangement.

The rabbi took on his butcher critics head on. “The very fact that the butchers object to regulations about kosher meat shows that they wish to sell other meat in its stead,” he asserted. “If they were honest in this matter, what difference is it to them whether the meat prepared according to the regulations of our law is marked or not?”17

Equally worrisome, though, was the reaction of many housewives. The plombe had an analogue in a hated practice many immigrant Jewish women remembered all too well from Russia. It seemed for all the world like the karobke, a punitive tax on kosher meat administered by the kohol ostensibly to support the Jewish community, but sometimes diverted by the government for use to their detriment.18 To them, the penny tax seemed less a service fee than an attempt at gouging. Rabbi Joseph was accused of adding a layer of corruption to an already crooked system, and one that worked to his own benefit and that of his cronies.

The plombe was no more popular with mashgichim who were not under Joseph’s supervision, who would not only not profit from it, but stood to lose business because of it. And of course, the slaughterers and butchers who played fast and loose with the rules were dead set against it. Forty-six butchers who refused supervision even set up their own organization, the Hebrew Poultry Dealers’ Protective Benevolent Association, to fight the new scheme, and they had the support of three rabbis from congregations not under Rabbi Joseph’s authority. After they heard a rumor that Joseph had ordered members of his association’s synagogues to boycott butchers whose poultry failed to display his plombe—something Joseph denied ever doing—it seemed to them that they were fighting for survival.

In January 1889 Samuel Pincus, the head of the Poultry Dealers’ Association, sought a sit-down with Rabbi Joseph to try to come to some sort of accommodation, but the rabbi refused to meet with him. In retaliation, Pincus’s fellow members voted to declare all meat sold by those “who made common cause with the charlatans who impose the karobke” to be treyf. He told the New York Sun they were considering legal proceedings against Joseph, and a representative of his association even paid a call on the District Attorney’s office to discuss the possibility.19

Some uptown Jews were also critical of the plombe. “It is said that the taxes are excessive, illegal and stamp the whole movement as a business. It is not a question of kosher, but of a tax,” the Jewish Messenger opined.20 A letter to the same publication criticized Joseph for being in the pocket of the businessmen who had helped him discharge his debts in Europe and were paying his salary. The writer maintained that Joseph “is making the poorer class suffer for the benefit of his favorites. The quicker he abandons his imported Russian method of taxation, the better it will be for all concerned.”21

But uptowners from some Orthodox German and Sephardic congregations, many of them rabbis themselves, were supportive, even though they didn’t accept Joseph’s jurisdiction. In an open letter published in the Jewish Messenger on February 15, twenty-six prominent uptowners appealed to all observant Jews to “assist in order that the good work may be extended, and those difficulties removed which hinder uptown Hebrews in obtaining meat and poultry kosher beyond suspicion.” They even convened a public meeting and invited Joseph to address them.22

Far from being cowed by the criticism, Joseph pressed on with more reforms. He attempted, with some success, to assert authority over the abattoirs that supplied kosher beef, hounding out shoychtim who did not meet his standards and certifying new ones, expanding inspections and extending use of the plombe to beef, although in this case no extra charge was assessed. By early 1889 fully eighty-six slaughterhouses and butchers were operating under his supervision. Those butchers were licensed with a hechsher, a certificate bearing the rabbi’s signature placed conspicuously in their workplaces that testified to their adherence to the laws of kashrus. For this, he charged them four dollars per month ($106 today).23

In March, however, Joseph backed down from charging for supervision certificates. After all, his independence had stemmed from the fact that he, at least, was paid by the congregations and not by anyone in the meat business. But this move cut into revenues. To make up the difference, he decreed that flour used to make matzoh for the following month’s Passover holiday would be subject to an inspection charge of one dollar a barrel. It was another unpopular move that was interpreted as a money grab.24

By most accounts a pious and sincere man, Rabbi Joseph was utterly trounced in the court of public opinion. With the wide acceptance of the equation between the plombe and the karobke, he had lost the battle. A greenhorn who spoke no English, he had failed to appreciate the differences between America and Eastern Europe, and he turned out to be no match for those in its fragmented Jewish community with vested interests. “New York is not Vilna, and America is not Russia,” the Jewish Messenger declared derisively.

It was all downhill from there. Reviled by a sizable contingent of the community, Rabbi Joseph was left with the support only of those Orthodox congregations that had invited him in the first place, and even they eventually began to balk at how much he was costing them. By the early 1890s they did not feel able, nor did they feel it was fair to them, to finance kosher supervision for the entire city. To extricate themselves from the sizable financial commitment their association had made to the rabbi, they negotiated a new arrangement whereby butchers would pay a portion of his salary and those of the mashgichim who were working for him.

This, of course, thoroughly undermined not only his perceived objectivity, but his authority. And when a contingent of Hungarian and Galitzianer congregations named their own “chief rabbi,” his influence declined even further. Then a third “chief rabbi” emerged in 1893 to preside over a few Hasidic congregations. Asked who had endowed him with the title, the man replied sheepishly, “the sign painter.”25

Even Joseph’s new compensation scheme dissolved in 1895 when one of his rivals offered butchers cheaper supervision. Joseph was deposed from his position. He did not return to Europe, however; he was simply left to fend for himself as a mashgiach.26

After this, New York’s kosher meat industry more or less reverted to its original chaotic state. The system Rabbi Joseph had failed to fix remained divided and broken. But soon the Lower East Side would face a new existential threat to its supply of permitted meat that would revolve around price rather than quality. The culprits would also be men in the meat business. But this time they would not, for the most part, be local butchers, but rather a handful of men in Manhattan who did the bidding of gentile businessmen eight hundred miles away in Chicago.