5

A Despotic Meat Trust

Throughout 1901 the East Coast had experienced a gradual rise in the price of beef, but in early 1902 there was a quantum jump in the rates. By the end of March the wholesale price had climbed from seven to ten-and-a-half cents a pound (from two to almost three dollars in today’s currency), a 50 percent increase. This increment, of course, was passed on to consumers by their butchers. Early 1902 therefore saw a lot of hand-wringing, but there was little mystery about who was responsible.

“The beef business in this country amounts annually to something like $600,000,000,” ($17.6 billion today) the New York Sun told readers, “and it is almost entirely controlled by four firms: Swift & Company, Armour & Company, Nelson Morris & Company and G. H. Hammond & Company. It is alleged that these firms have an agreement which makes it possible for them to boost the price of fresh meats whenever they want to.”1

Butchers certainly felt the effects of the price hikes; hotels and restaurants did, too, but unevenly. Large hotels suffered the least; they had signed long-term, fixed-price contracts with suppliers. But smaller establishments were hit hard. “I have stood it about as long as I can without losing money,” one restaurateur told the New York Tribune. “In a few days, I shall have to charge my customers more for their meat. I am forced to do so by the unreasonable men back of the Trust,” he said, adding, “they ought to be dragged before a jury of householders.”2

Tammany Hall, the Democratic machine with an iron grip on New York City politics, saw an opportunity to hang the problem on the Republicans in Albany and Washington. Citing several nefarious practices attributed to the Trust—the blacklisting of dealers attempting to act independently, the manipulation of prices through secret agreements, the cornering of the market, and the signing of illegal, discriminatory freight contracts with railroads—it called on the Republican attorneys general of the state and the nation to take action against it.3

New York State did get into the act. Governor Benjamin Odell instructed Attorney General John C. Davies to look into the causes of the steep rise in beef prices. As Davies told the New York World, “the Governor is very much opposed to any high-handed proceedings by the Trust, and he is willing to endorse any legal steps to protect the interests of the people.” He added, “it is criminal for any body of men to create a monopoly on a commodity that is essential to the maintenance of life, and if I find that this is really the case, I shall proceed against them on the ground of restraint of trade and of carrying on a business injurious to public policy.”4

Many others joined the chorus. The Board of United Building Trades, which represented seventy-five thousand workers, passed a resolution in early April condemning the “selfish and grasping policy of the Beef Trust.” The New York City Board of Aldermen strongly condemned “the inhuman action of the combination known as the Beef Trust” and demanded intervention by federal and state authorities. The assemblymen of Hudson County, New Jersey, debated asking the state legislature to nullify the charter of one of the Trust companies domiciled in the state. And Newark, New Jersey, butchers resolved to buy their own cattle and bypass the Trust entirely.

Nor did all the criticism come from the New York area. The Central Labor Union of Boston adopted an anti-Trust resolution. Kansas farmers organized to fight. And congressmen from Tennessee introduced a bill to abolish all duties on foreign meat imports to give the Trust some competition. The list went on and on.5

The grumbling did not go unnoticed in Washington. The situation seemed so blatant, and the protests so widespread and vehement, that President Theodore Roosevelt, who had suddenly ascended to the presidency the previous September upon the assassination of President William McKinley and who was suspicious of big business and no friend of trusts, attempted to put the brakes on meat prices. “President Roosevelt,” the St. Louis Republic told readers, “is making this his personal fight for the ‘full dinner pail.’” It was a reference to a slogan the 1900 McKinley campaign had employed to appeal to working class voters.6

Early in April, under instructions from Roosevelt, Attorney General Philander C. Knox ordered the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Illinois to open a secret investigation to determine whether the Beef Trust was violating federal antitrust law. It didn’t take long. Before the month was out, Knox had gathered enough evidence against the Trust to satisfy himself that it was acting as a “combination in restraint of trade.”

On April 24, after calling at the White House to brief the president, he directed the filing of simultaneous lawsuits under the Sherman Antitrust Act against Swift & Company, Armour & Company, the G. H. Hammond Company, and Nelson Morris & Company in Chicago; the Cudahy Packing Company in Omaha; and Schwarzschild & Sulzberger in New York. The goal was to put a stop to their anticompetitive practices—specifically creating monopolies, fixing prices, and dividing territory.7

The meat packers, of course, had their own version of why prices had risen so steeply. In an article in National Provisioner, their industry journal, they denied working in concert and argued that there was no such thing as a “Meat Trust” in the first place.

9. A cartoon by Charles L. Bartholomew showing Pres. Theodore Roosevelt holding a gun while a cow labeled “Beef Trust” sits on the moon reading a newspaper (ca. 1902). The headline reads: “Beef Is Way Up.” The caption reads: “The Beef Trust—Don’t shoot, I’ll come down.” Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-37841.

It has been charged that five big packing concerns form a despotic Meat Trust that drives all competition to the wall, puts up prices at will, and that this combine, by one stroke of the pen, so raised prices as to take $100 million [nearly $3 billion today] extra out of the helpless consumers’ pockets and added it to its already profitable greed. There is no such Trust. . . .

The price of live cattle makes the wholesale price of beef. The raisers of cattle make the price in the market. . . . Cattle are high. That makes beef so. They are also scarce and our export as well as home demand being great, the price of livestock goes up.8

Ferdinand Sulzberger, president of Schwarzschild & Sulz-berger, which had been established in New York in 1853 and was considered the sixth member of the “Big Six,” also defended the packers. He told the Daily People, the official organ of the Socialist Labor Party of America, that companies like his were actually losing money, and blamed it on an anemic corn crop that had depressed the population of livestock and raised its purchase price. “Last year, a 1,500-pound bullock cost five and a half cents a pound alive; today he costs seven cents. It costs $6 to get the beef killed and laid down in New York; we get $15 for the hide, fat and offal. The cost, then, is close to ten and a half cents a pound in New York. The margin between cost and selling price today is less than it was last year. Then we could make $2 on each live beef of 1,500 pounds. Now that margin has shrunk so there isn’t any margin left.”

In other words, he claimed his firm wasn’t making any money on city-dressed beef.

“There is nothing like an agreement between the different large packing houses to stifle competition,” he insisted. “There is no agreement to fix prices.” But when pressed, he more or less admitted collusion. “Well, of course we may not compete so much at some times as others. Not to fight is a different thing, isn’t it, from working together?”9

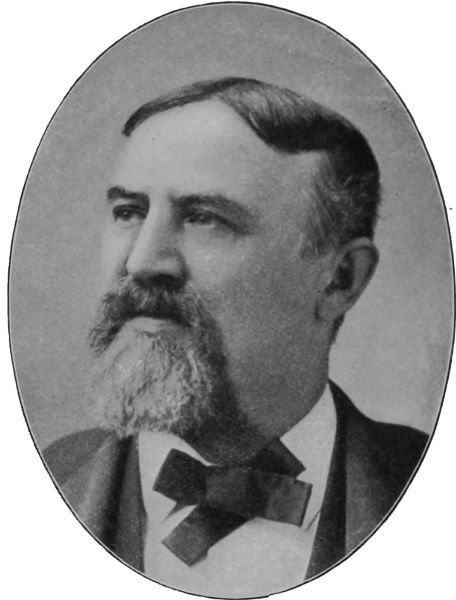

10. Ferdinand Sulzberger, president of Schwarzschild & Sulzberger. Source: Notable New Yorkers of 1896–1899 (New York: M. King, 1899).

In fact, it wasn’t. A St. Louis meat dealer, speaking with the same publication, gave the lie to Sulzberger’s claim. “The packers buy cattle on successive days so that each can buy at his own price. There is very little independent buying. The big packers keep others out by telling the cattlemen that if they sell any cattle to the independent buyers, they must sell all to them.”

“The cooler managers meet every Wednesday afternoon and on Saturday. I do not know who fixes prices for them, but they are fixed the last day of the week for the week following. When a man does not sell his cattle in East St. Louis and ships them elsewhere, the packers send a dispatch ahead of him, instructing the buyers to only offer so much.”10

The nefarious activities of the Beef Trust were so widespread and so egregious that it was inevitable its methods would be exposed in the press. The New York Herald quoted materials obtained surreptitiously from a Cudahy manager that decried the fact that Armour was shipping beef outside its “territory,” explained how offering rebates only to large dealers was crushing smaller ones and described how members of the Trust were fined for violating the price agreement. The revelations were so damning that a senator from Oregon read them into the Congressional Record.11

A former employee of Swift & Company gave an insider’s view of the situation to the New York World. “The wail of the packers that they cannot buy the cattle as cheaply as formerly is bosh,” he asserted. “The packers pay the raiser just what they want to and no more. There is no competition in buying cattle.”

“For instance, Armour’s buyer will come along and offer the cattle-raiser three and a half cents a pound on the hoof. The raiser will refuse to take it, believing that Swift’s buyer will pay four cents. But Swift’s man will only offer just what Armour’s man offered. These buyers are instructed by the big four packers in Chicago to pay just so much for cattle. If the raisers refuse to accept it they cannot sell their cattle, so they are forced to accept in the end.”12

The meat packers had the cattlemen exactly where they wanted them. They were using their combined marketplace might to squeeze them as hard as they could by refusing to bid against one another and retaliating against any who tried to go around them. There was no cattle shortage, and producers were no more responsible for the rise in meat prices than were the housewives who bought flanken on Hester Street. The culprit was the Trust, which stood between them, operating behind the scenes to depress the cost of cattle and raise the price of meat in the cities.

And denying it all.

With a federal lawsuit pending against them, one might have expected the Trust companies to have lain low for a while, but in April they made another brazen and aggressive move. In response to the steep rise in beef prices, consumers were turning to alternate sources of protein. Many had switched to poultry, veal, mutton, lamb, eggs, and, in the case of non-Jews, pork and lard. Determined to frustrate this move, which cut into profits, the Trust also effected a price rise for some of these commodities, something it was able to do because many of them also passed through its slaughterhouses or came to New York in refrigerator cars it owned or controlled.

It was able to raise pork two cents a pound (nearly fifty cents in 2019 currency) and mutton, veal, lamb, and lard a half to three quarters of a cent (about thirteen to twenty cents today). Swift and Armour began to buy up and stockpile eggs to depress the supply in the market. Fifteen cents a dozen ($4.40) in 1901, they now sold for eighteen cents ($5.25). By one estimate, eggs alone increased Swift’s profits by $36,000 (just over one million in 2019 dollars) with every one-penny rise.13

“Among the homes of the workingmen on the West Side, the effect of the rise in the price of a meal is painfully apparent,” the World reported. “Families which have been accustomed to having meat on the table twice a day are now forced to get along with a meat stew once a day. To them, steaks are barred. Roasts are out of the question. A roast of beef for a family of six costs $1.75 [fifty-one dollars today]. Steak, rump or shoulder cuts, for the same family for one meal, cost sixty-five cents [nineteen dollars].”14

But things were even worse on the East Side. Everyone was feeling the pinch, but the Jews, with fewer options, were feeling it more acutely than others. Kosher meat had always been more expensive, and many Jewish families were living so frugally that they simply couldn’t spare the extra pennies. Nor was the situation helped by the imminent arrival of the Passover holiday on April 21. It was common for meat to be served with the ritual seder meal, and so demand was likely to rise and put further upward pressure on prices. With the price of a pound of brisket now hovering around eighteen cents, Jewish housekeepers were approaching the normally festive holiday with a good deal of anxiety.15

Passover’s arrival was governed by the Jewish lunar calendar. In 1902 the eight-day holiday was to begin on April 21, a fact that raised an additional problem for Jewish families because the first and last day both fell on Mondays. Jewish law forbade butchers from working on Saturdays, but the state’s blue laws, which prohibited the sale of alcohol and closed bars on the Christian day of rest, had been amended the previous year to prohibit butcher shops from doing business on Sundays as well. As a practical matter, Sunday closure laws were often honored in the breach in New York City, where a gratuity could persuade a corrupt policeman to look the other way. But the police had been especially aggressive lately. On April 13 they had arrested fifty-eight shopkeepers and pushcart salesmen, many if not most of them Jews, for doing business on a Sunday.

The reason the new law was problematical was that it meant that Orthodox Jewish housewives would have only a very brief window—a few hours after sundown on Saturday, after Shabbos had officially ended—to purchase meat slaughtered the previous Friday for their Passover tables.

Simon L. Adler, a Jewish state assemblyman, had tried to get the law amended to permit kosher butchers to open for a few hours on Sundays, but his effort failed. The arguments marshaled against it included the fact that no civil law required the Jews to close on their Sabbath, and that permitting them to remain open on Sunday would give them a monopoly on Sunday sales to the detriment of gentile butchers.16

A hue and cry arose on the Lower East Side as the community anticipated the difficulty of celebrating the coming holiday with meat on the table, and the matter came to the attention of Mayor Seth Low, who decided to offer relief, even though the problem was a state law, not a local one. Surely with an eye on the Jewish vote, which had helped elect him, the Mayor wrote Police Commissioner John N. Partridge:

I am reminded that the Jewish Passover festival begins this year on Monday next, and lasts until, and including, Tuesday, April 29. The Monday and Tuesday of both weeks with the Jews are holy days, as well as the Saturdays, and upon these days the devout among them keep their shops closed. In the meanwhile, it is a requirement of their religion that they secure meat specially prepared, which under the circumstances, can only be had upon the two Sundays for use upon these days, thus compelling the devout Jew to choose between obeying the dictates of his conscience and the letter of the statutes of the State.

He essentially ordered the police not to enforce the state law.

The kosher butchers were grateful for the respite, but permission to open for an extra day did not solve their larger problem. They still had to pay much higher prices for meat, and worse, they were also now being forced by the slaughterhouses to pay cash on the barrel; the customary two- to three-day grace period was no longer being extended. They had no choice but to raise prices, but many of their patrons couldn’t afford to pay more. As one butcher put it to a reporter, “We are entirely discouraged. Our customers cannot do as they do across town or uptown—merely grumble a little, pay more, and go on buying. No, they cannot do that, for they do not have the money to buy with.”

11. New York City mayor Seth Low. Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62–36674.

The butchers were feeling the heat. Kosher butchers generally operated from month to month and did not have significant reserves to enable them to weather a lengthy downturn. Many had already gone out of business; others whose leases would expire on May 1 knew they wouldn’t be able to renew them.

It was time for a concerted effort. If they wished to stay in business, there was really no other choice but to fight back.