12

No Industry in the Country Is More Free from Single Control

As U.S. Attorney Solomon H. Bethea prepared to argue the federal case for a temporary injunction against the Big Six packers in Chicago, several states also got into the act. Missouri instituted its own investigation. The Ohio legislature passed a new antitrust measure aimed at the Beef Trust. And New York Attorney General John C. Davies launched an investigation of the Trust for possible violation of state antitrust legislation.1

By mid-May, Davies was ready to move ahead, and to increase his chances of success, he bifurcated his effort. He requested the New York State Supreme Court in Albany to appoint a referee—a retired judge—to determine whether prosecution to revoke these corporations’ business certificates was warranted. And he instituted a formal action against the Trust that would be heard by a sitting state supreme court justice.

In the first instance, ex-Justice Judson H. Landon was chosen to hear witnesses, all of whom would be testifying for the state. And Justice Alden Chester would hear from both sides in the formal case.2

On the morning of May 15—the very day the protests in New York City began—Justice Landon heard testimony from Andrew W. Gerlach, a New York City retail butcher who had done business for twenty-seven years with all the companies of the Trust. Gerlach asserted that when the wholesale price of beef began to rise on January 1, all the companies raised it simultaneously, in lock step. He also described a dispute in which a Swift & Company agent told him he had been placed on a credit blacklist. Thereafter, no Trust member would do business with him except on a cash basis.3

While the hearing was adjourned for lunch, however, Davies received a telegram from U.S. Attorney General Philander C. Knox asking that testimony of Daniel W. Meredith, a Jersey City–based former employee of both Swift & Company and Armour & Company and one of Davies’ key witnesses, be postponed. The Justice Department intended to argue the federal case before the Seventh Circuit Court in Chicago on Tuesday, May 20, and Knox didn’t want Meredith to tip his hand before that. In light of the request, Davies asked Justice Landon to adjourn until May 22.4

But there was no bar to continuing the case before Justice Chester. Davies hadn’t made his witness list public, but it was widely rumored that the star witness under subpoena would be Arthur Colby, allegedly the Trust’s New York City–based “arbitrator,” the point person who set the prices Trust members were required to charge for beef in the Eastern region. Colby, it was believed, had the authority not only to fix prices, but also to impose fines on constituent companies that violated the packers’ agreement.

Also on Davies’ witness list were the New York representatives of the Big Six—Armour, Swift, Cudahy, Hammond, Schwarzschild & Sulzberger, and Morris. And on May 13 he had dispatched a representative from Albany to New York City to serve subpoenas on all of them.5

There was just one problem. The men were nowhere to be found.

Despite repeated visits to their homes and places of business over two consecutive days, the server could neither locate them nor learn their whereabouts. Nobody would say where they had gone. Davies had been assured that they would welcome his investigation as a means of clearing themselves of allegations of wrongdoing, but their disappearance suggested otherwise.6

“The developments of the last few days have convinced me that the companies are afraid of a judicial inquiry, and their representatives have placed themselves outside the jurisdiction of the court,” he told Justice Chester. Under the circumstances, there was no immediate way to proceed, so Chester, too, was forced to postpone his hearing. He set Monday, May 26, as the date to reconvene.7

As all of this was happening, news came out of Chicago that beef prices had broken all previous records. “This advance,” the New York World insisted, “is plainly an arbitrary decree of the Trust, as the supply of cattle in the stockyards is as large as usual.” And the paper published the numbers to prove it.8

On Sunday, May 18, the day before the federal case was to be presented in Chicago, both the Chicago Tribune and the New York Herald, in cooperation, published a blockbuster story. The papers had somehow gotten hold of internal Armour & Company correspondence. The Herald promised the letters would be turned over to the Attorney General for use in the federal case.

But not before the papers gave their readers a taste of what was in them.

The file included thirty letters to and from Armour executives in several eastern and midwestern cities. Code names were used for each Trust member, but it wasn’t hard to figure out who was who. They told a tale in black and white of a conspiracy among the so-called competitors to control the price of meat, parcel out territory, act in unison against “outsiders,” and be sanctioned for any violations of their agreement.9

Attorneys at the Justice Department were jubilant when they learned of the scoop, which essentially made most of their case against the Trust. Assistant Attorney General William A. Day, who was to help argue the case for the government, declared that the new evidence proved the existence of an agreement to raise and maintain prices in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Law. “It shows the existence of a hard and fast combination between the six great packing houses not only to regulate prices, but to divide territory,” he said. “I consider this a very important contribution to the campaign.” After reading the coverage, Solicitor General John K. Richards took off for Chicago to help Day and U.S. Attorney Bethea make the case.10

The next day, the papers reported that when Colby and the six Trust companies’ New York managers disappeared from the city, they had taken with them all of the books and papers they had been ordered to produce as evidence by Justice Chester in Albany. The men had not gone far, however. They had simply moved their headquarters, lock, stock, and barrel, across the river to Jersey City and Hoboken, conveniently out of reach of the New York judicial system.

As for the office of the arbitrator, its “complicated network of special telephone, telegraph and ticker wires” that connected Colby with more than sixty Trust branch offices in New York, Brooklyn, and Jersey City was impossible to pack up and move overnight. But all of the books and papers—including records of fines imposed under the Trust agreement—had been removed to Jersey City, and Colby himself, it was reported, had left on a long vacation, destination unknown.11

The Herald explained that the reason for the exodus was that the Trust members feared that information revealed at the hearing before Justice Chester in Albany would prejudice their federal case in Chicago. As far as the New York World was concerned, however, the move was an admission of guilt. “Removal is confession,” it declared on its editorial page. “The Beef Trust is on the run.”12

The publication of the Armour correspondence blew a huge hole in the strategy the Trust’s lead counsel, John S. Miller, had intended to use in court. The packers had vowed to fight a temporary injunction by denying that any cooperation agreement existed. Now, in the face of incontrovertible evidence to the contrary, they changed their tune. They would now admit the allegations, but argue that their activities did not violate the Sherman Antitrust Act.13

On Tuesday, May 20, in an unusually crowded courtroom, Judge Peter S. Grosscup called the case of United States v. Swift & Co. et al. U.S. Attorney Solomon H. Bethea laid out the government’s evidence against the defendants, claiming they controlled 60 percent of the nation’s fresh meat trade. He filed twenty-odd affidavits from people formerly employed by Trust companies, the most damning of which was from Daniel W. Meredith, the witness whose testimony the Justice Department had asked New York to defer. Meredith’s statement revealed that the six New York–based general managers of the defendant companies had met weekly since 1893 to set prices for the week to come. Whenever they felt it was advantageous to raise prices, they agreed to curtail meat shipments from Chicago and points west to reduce supply.14

Other affidavits were from two former Nelson Morris employees. One claimed to have transcribed an 1888 agreement between three Trust companies binding them to meet regularly with an arbitrator to maintain prices, pay fines for violations, and share information about discharged employees. The other had had the duty of translating coded telegrams from other Trust members.15

Taken together, they were an extremely damning set of documents.

Bethea asked the judge to bar the Trust companies from further collusion. Attorney Miller did not object to the issuance of an injunction, though he did assert brazenly and disingenuously that “no industry in the country is more free from single control.” He claimed that because he had not been afforded the opportunity to examine the government’s affidavits in advance, he was not prepared to refute them. But he objected to the government’s assertion that the defendant companies controlled 60 percent of the nation’s packing business—he insisted the figure was closer to 40 percent.16

So at 3:00 p.m. Judge Grosscup issued a temporary order enjoining the companies and their agents from “entering into, taking part in or performing any contract, combination and commerce in fresh meats” by:

24. A sketch of the courtroom scene in the Beef Trust case. Source: Chicago Tribune, May 21, 1902.

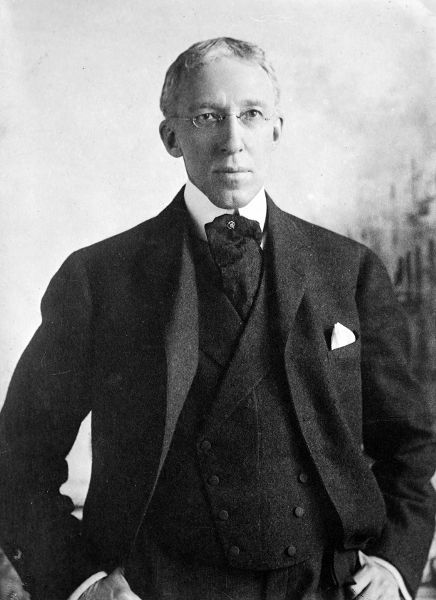

25. Judge Peter S. Grosscup. Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, George Grantham Bain Collection, LC-DIG-ggbain-06248.

- instructing their agents not to bid against one another in the purchase of livestock;

- arbitrarily raising or lowering prices or fixing uniform prices;

- arbitrarily curtailing the supply of meat shipped;

- posing penalties for deviations from agreements;

- establishing uniform rules for credit;

- imposing uniform charges for delivery; or

- obtaining rebates or special rates from the railroads.17

It was a total victory for the government. Day, the Justice Department’s special counsel, gave the press his interpretation of the Trust’s languid defense. “It means that the government’s case is more than the counsel for the packers cares to tackle.”18

Attorneys for the packers did not tip their hand about their next move, which in any event would not have to be revealed for several months, since the companies had been given until August 4 to reply to the basic complaint.19

Whether they would comply with the terms of the injunction was an open question, but they would be subjecting themselves to substantial penalties if they failed to do so. They would be subject to being held in contempt of court, and the burden of proof that they had not violated the order would be on them rather than on the government.

Nothing about their history, however, suggested that they were the sort of companies to simply roll over and play dead.20