19

We Don’t Feel Like Paying Fifth Avenue Prices

No press reports chronicle how many kosher butchers ultimately signed the pledge to sell meat at fourteen cents a pound as long as the wholesale price permitted it, or how many certificates were issued by the Allied Conference. Indeed, there is no record of any formal announcement by the organization that the protest was officially over. If the movement had begun in mid-May with a bang, it had ended by mid-June with a decided whimper. But there could be no arguing with the fact that its overarching goal had been achieved, at least in the short run.

The wholesalers had come to terms, and kosher meat was affordable once again.

But why had wholesale prices come down? Certainly a key factor was the relentless pressure of the boycott, which did a remarkably effective job of suppressing demand. This, in turn, meant that wholesalers weren’t doing much kosher business in New York, and that their profits were down, as were those of the Midwestern houses from which they bought cattle. Since the whole point of raising prices had been to increase profits, that plan was clearly no longer working for the Trust companies, and abandoning it, at least for the moment, made good economic sense.

But all this occurred within the larger context of the dismantling of the mechanisms they had used to fix prices that was mandated by the injunctions against them. Without the ability to coordinate and set artificial prices, the Trust companies once again found themselves at the mercy of market forces. Those that offered retailers the best prices would be the ones that did business. Put another way, to the extent that the mechanisms the Trust companies had dreamed up to foil the laws of supply and demand were no longer operative and had not been replaced by winks and nods, those laws once again governed the market.

And market forces were the boycotters’ best friend.

As long as this was the situation and regular retail butchers sold meat at affordable prices, there was no longer any pressing need for organizations to fight price hikes or, for that matter, much of a need for cooperative shops. And indeed, within a month or two there were no further references in the press to the Ladies’ Anti-Beef Trust Association or the Allied Conference for Cheap Kosher Meat. Not even the new cooperative butcher shops appear to have had much staying power. The city directories list a meat shop at 245 Stanton Street through 1905 and one at 57 Monroe through 1906, but not afterward.1

Anyone who expected the Beef Trust to roll over and play dead in response to temporary restraining orders, however, wasn’t reckoning with the greed and guile of the men who had built it up in the first place. Although the Big Six were technically complying with the orders of the federal and state courts, that didn’t mean their bosses weren’t huddled with their lawyers plotting ways around them.

The question of whether the federal injunction against them would become permanent remained before Judge Peter S. Grosscup for the balance of 1902. Finally, in February 1903 he rendered his decision. Taking a broad view of interstate commerce, he concluded that the Trust companies were, indeed, acting in restraint of trade as envisioned under the Sherman Act. Accordingly, he granted the government’s motion for a preliminary injunction against them. In May, he made it permanent.2

But the Trust’s men had another tactic up their sleeves. If it was unlawful for independent firms to collude, why remain independent? A new structure in which the companies consolidated and were commonly owned could solve the problem handily. And as a first step, three of the Big Six—Swift, Armour, and Morris—decided to form a holding company. They incorporated it quietly in New Jersey in mid-March 1903, and named it the National Packing Company.

All but two of the new company’s directors were officers of Armour, Swift, and Morris. In fact, four of the eleven directors were named Armour, Swift, or Morris. Capitalized at $15 million dollars ($400 million in 2019 dollars), the corporation began by merging small meat companies in Chicago and Omaha the three had purchased earlier. It was a first step in a slow but measured strategy designed eventually to bring everything under one umbrella. At its formation, seven companies were placed under its aegis, G. H. Hammond Company of Chicago and the United Dressed Beef Company of New York among them. Everyone assumed the new arrangement would be the forerunner of a bigger merger to follow. The New York Tribune even ran the news under the headline “Start of Beef Trust.”3

A reporter from the Tribune asked Frederick Joseph, vice president of Schwarzschild & Sulzberger, for a comment on the merger.

“We feel satisfied with our present business,” he replied evasively.

“Was an offer made for your company?” the journalist asked.

“Well, I would rather not talk about that,” Joseph replied.4

There had indeed been discussions with Schwarzschild & Sulzberger and with Cudahy, but these companies ultimately remained independent. Four of the “Big Six,” however, had now joined forces.

Their effort to combine assets notwithstanding, the Trust companies still wished the injunction against them to be lifted. Accordingly, on July 18, 1903, they appealed Judge Grosscup’s decision to the Supreme Court of the United States. Throughout 1904, while the appeal was in process, the Justice Department—now under the leadership of Attorney General William Henry Moody, Philander C. Knox having resigned to accept an appointment to the Senate—was watching carefully for any further violations of the antitrust laws.5

Whatever the cause of the return to reasonable meat prices—whether it was the strike, the appearance of co-ops, or the injunction, or, most likely, a combination of all three—they continued to prevail for several years. But the financial pressures on East Side families did not abate, and in early 1904 a new threat emerged when rents began to rise abruptly.

Landlords had begun demanding ten dollars a month ($280 in today’s dollars) for flats that had formerly let for $7.50; apartments that had cost $5.50 had risen to $7.50. Leases were rare, so landlords could raise rates at will. And with shelter being most families’ greatest expense, rent rises averaging 25 percent posed even more of a threat to the lives of East Side families than had the increase in butchers’ charges two years earlier. There were nearly eight thousand evictions on the East Side alone in 1903, and 1904 threatened far more.6

It was market forces, however, rather than some unseen corporate trust, that were primarily responsible for the rise in rents. New York’s growing population of immigrants was chasing too few flats. More than 600,000 aliens, mostly immigrants, arrived at Ellis Island in 1904 alone. The city’s population had expanded by more than 14 percent just since the turn of the century, even as tenements on the East Side were being torn down to make way for parks, schools, and the new Williamsburg Bridge.

In addition, the government had added to building owners’ financial burdens with the passage in 1901 of the Tenement House Act, which not only introduced specifications for new buildings, but also required significant upgrades to existing structures, including installation of indoor toilets, windows, fire escapes, hall lights, and waterproof cellars. And because builders and contractors had been on strike since 1903, the pace of new construction had slowed.

The first of the month was when rent was generally due, and so it was also normally the time that suits were filed against tenants, and marshals posted eviction notices on their doors. It was often not the building owners themselves who took legal action, but rather speculators who signed leases with them for entire tenement blocks and decided on their own how much to charge for the flats. As far as the renters were concerned, the speculators were the ostensible landlords, and many of them were fellow Jews, widely disliked and derided on the East Side as “cockroaches.” Positioned between the owners—some of whom were also Jewish—and the tenants, it was they who had the strongest incentive to squeeze the renters.

The tenants sensed a conspiracy. They believed the lessee landlords were exploiting the situation, just as the retail butchers before them had victimized the meat strikers. As a Mrs. Wexelman put it at a meeting organized to consider a rent strike, “the East Side landlords and agents have a secret organization and a blacklist. Their plan is to make it so uncomfortable for anyone who refuses to pay the increased rents that it will be impossible for him to live on the East Side. Many of us must live down here, but we don’t feel like paying Fifth Avenue prices,” she added.7

No one who had lived on the East Side for more than two years could fail to grasp the striking parallels between meat in 1902 and rents in 1904. And as the drama played out over the next month, the similarities became even more evident. Once again, the people of the Lower East Side perceived a grave threat to their welfare, and once again they rose up to fight. Once again they felt exploited and saw other Jews as their enemies. Once again socialist agitators would attempt to use the movement for their own ends. Once again the organizers would be denied the right to hold rallies, but would be remarkably successful in building support by going door to door. Once again cooperatives would be prescribed as a solution to the problem. And once again a previously obscure woman would take center stage to mobilize her community, but ultimately be sidelined by better-connected men.8

This time they had a model from which to work. The successes—and the blunders—of the meat boycott were still fresh in memory, and much of the violence that had marred the earlier movement could be avoided. During the meat boycott, it had taken several days of riotous demonstrations before the established organizations came together to address the issue; this time the community was largely able to short-circuit trouble in the streets. On April 6, delegates from several East Side organizations assembled. Several were Jewish groups; others were unions with large Jewish memberships.

The Forward made the parallel explicit and encouraged the protest. “This strike can be as great as the meat strike,” it asserted, urging the women to “take the rent question into their hands as they did the meat question.”9

In the same way that the Allied Conference for Cheap Kosher Meat had been established in 1902, the delegates voted to establish the New York Rent Protective Association to act on their behalf. They also decided to ask for a permit for a large protest parade and an open air anti-landlord rally to be held in Seward Park on the following Monday, April 11.

Samuel Katz, an East Third Street machinist, was named president, and a young woman named Bertha E. Liebson was elected treasurer. Only seventeen years old and Russian-born, Liebson, the daughter of a cloak maker, possessed boundless energy. She had immigrated in 1900 and her day job was as secretary of the New York Protective Association, a labor union advocacy group. But she became a local folk hero for all of the time and effort she had invested raising funds to hire counsel to defend tenants whose eviction hearings were scheduled for the week after Passover. Just as the New York World had given Paulina Finkel the sobriquet “the Napoleon of the East Side” in 1902, papers now dubbed Bertha Liebson “the East Side Joan of Arc.”

“I am going to devote everything a girl can to the poor tenant and to defeat the landlords,” she vowed during the meeting, “and I mean to win!” She also pledged to recruit more females into the association. To that end, she helped canvas the quarter and distribute thousands of flyers in English and Yiddish, reminiscent of those produced by the Ladies’ Association to ask fellow Jews to boycott the meat shops. The New York Sun printed an example: “Tenants, keep away from this house. In the name of your children we ask you not to hire any rooms in that house, as the house is on strike because the rent is raised every month, and we want to put a stop to it once and for all. Keep away!—The Committee.”

An unnamed rabbi told the Sun that “we are advocating arbitration because unless there is an amicable and fair settlement by some such method, there is likely to be serious trouble in the East Side within a week. We had violence here during the so-called kosher meat riots two years ago,” he continued, “when butchers were beaten in the street and their stores wrecked. The present increase in rents is a much greater hardship than was the increase in meat prices. But the causes are similar.” He went on:

Many of the landlords are Jews who began buying East Side property ten and twelve years ago, when it was much cheaper. The landlords have exaggerated the increase in their own expenses and tried to throw dust in the eyes of the people. An increase of five percent might have been justified. They ask twenty percent. The people . . . are organizing, which is a good thing if the organizations don’t fall into the hands of the agitators and become incited to violence. That is what we will strive to prevent. We hope to convince the landlords that public opinion will be too much for them and that they will hurt their own pockets in the end by driving the people away.10

The next day, Samuel Katz outlined the Protective Association’s plans. The group would encourage people to organize individual tenants’ associations to fight their landlords. And it would establish “an immense mutual benefit society for the Jewish tenants of the East Side” to help those who received eviction notices defray expenses and retain legal counsel. As the mutual fund grew, the organization would lease the houses and sublet them to the members at cost, and then, in time, buy and build its own buildings. It was an exact analogue to the cooperative butcher shops the Ladies’ Anti-Beef Trust Association had established in 1902 as a solution to rising meat prices.11

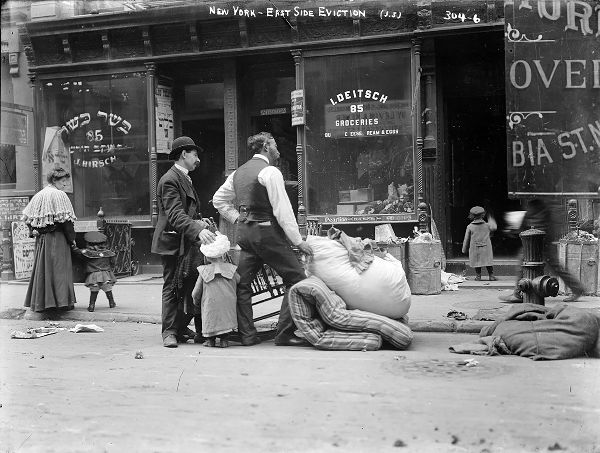

31. A tenant is evicted from 85 Willett Street. Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, George Grantham Bain Collection, LC-DIG-ggbain-01361.

Both Joseph Barondess and Abraham Cahan got into the act, just as they had two years earlier. Barondess spoke at a rally of the Social Democrats, though the organizers of the Protective Association doubted whether their involvement would be an asset. And Cahan outlined to the New York Times a plan to fight every case in order to tie up eviction proceedings and clog the courts, thus adding to the costs of the “cockroaches.”

In a signed editorial in Worker, Cahan also provided some genealogical perspective, so to speak, on the rent strike:

When the Meat Trust raised prices to an unnatural level and the entire ghetto burst into protest, that protest was the child of our trade union movement,” he wrote. “The meat strike was the offspring of our trade strikes. This is the case with the present rent strikes. They are the outcome of that same spirit, the offspring of that same struggle against capital.12

Indeed, like the meat protesters before them, the tenants borrowed terms from the labor movement, referring to their action as a “strike,” calling their tenants’ associations “unions,” and labeling those who paid their rent increases “scabs.”13

But it was not only the protesters who drew lessons from the meat strike. The judges seem to have done so, too. They were far more indulgent with tenants than they had been with meat protesters, although clemency was made easier because there was little violence this time around. David Blaustein noted that “the courts showed such leniency to the tenants that even the weakest of them felt a sense of protection. The justices were not able to alter the right of a landlord to raise the rent when he so desires, but they did emphatically put a stop to the eviction of the sick and granted extension of time during the Jewish holidays to so many that it meanwhile became possible to organize a systematic campaign.”14

On April 9, young Bertha Liebson made a formal request for a parade and a demonstration to Police Commissioner William McAdoo, who had come into office when George B. McClellan, Jr. defeated Mayor Low and took over on the first of the year. She was summarily refused and vowed to appeal to the mayor himself. But like Paulina Finkel, Clara Korn, and Caroline Schatzberg before her, she got only as far as his secretary, who told her the decision was McAdoo’s to make.

“I do not see why we should not be allowed to hold parades and open air meetings,” she complained to the New York Times. “Our people are all law-abiding, and there would be no danger whatever in letting us meet to express our views in this way. We do not advocate violent methods, but are conducting our work along peaceful and orderly lines. I think the Commissioner is unjust in refusing to issue the permit.”

It was a speech worthy of the women who had had much the same to say about Police Commissioner Partridge in 1902. Like the Ladies’ Association before it, the New York Rent Protective Association foreswore violence. And this time around there had been little of it, although that didn’t mean that some lessee landlords didn’t peer over their shoulders nervously when they walked the streets of the East Side.15

And just as the Ladies’ Association had split apart in acrimony, so did the Protective Association. At a meeting at McKinley Hall on Sunday, April 10, it broke up over an argument about money. Samuel Katz turned on Liebson, claiming she was too young to handle the organization’s funds; she, in turn, denounced him as a socialist. Before the evening was over, the Katz faction, mostly labor union people, had walked out with the money and rented the hall next door for a meeting of their own. Bertha was eventually ousted by those who remained behind. Even this unpleasantness had a parallel in the exit of Sarah Edelson from the Ladies’ Association.16

When May 1 came, there were more heartbreaking eviction stories. There was also picketing and deliberate damage done to apartments. There was stone throwing and a few attacks on landlords, but nothing remotely on the scale of the meat protests. The Protective Association offered to engage the landlords in a meeting, even as signs emerged that many of them were starting to capitulate.

“We have the landlords on the run,” crowed Samuel Edelstein, secretary of the association. “Since we started to fight them, tenants in eighty houses have gone on strike, refusing to pay the higher rents, and have formed unions to protect themselves. In over 30 percent of the houses where the tenants rebelled, the landlords have signed leases which will prevent them from raising rents for another year,” he added. Separately, the New York Tribune reported the surrender of landlords who had rented to a group of 150 families pledged to resist eviction.17

Some landlords backed down entirely; others reached agreement with individual tenant groups on lesser increments or offered year-long leases that guaranteed against increases. Some tenants left the East Side entirely, heading mostly for Brownsville or Williamsburg. And others just paid the increases. By mid-May it was all over, and people on the East Side went about their lives once again.

“We are greatly pleased with the peaceful ending of this vicious rent war,” said an association representative. “It seemed at first as if we had a monster enemy to deal with, but the strength and efficiency of the organized tenants showed our power and compelled the landlords to settle.”18 Indeed, there was reason for celebration. They had managed to avoid the worst aspects of the meat strike and still accomplish their goal.

A second rent strike began at the very end of 1907, the new year being an obvious time for landlords to raise rents. It occurred, however, against the backdrop of the Panic of 1907, an economic recession characterized by runs on banks and a rise in unemployment. The New York Times estimated that some 100,000 men and women on the East Side were out of work; they could ill-afford even modest rises in rent, and actually needed reductions.

A twenty-year-old socialist firebrand named Pauline Newman, who would later be remembered as a prominent labor activist and the first female general organizer of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, led the effort to push back on landlords. Although she was employed in a shirtwaist factory on Grand Street by day, she visited tenements in the evenings to organize the housewives.

The plan was for everyone to refuse to pay rent unless it was reduced by 18–20 percent. Once again, it was a page right out of the 1902 meat boycott. And borrowing from the earlier rent strike, Newman and the other organizers urged those who received dispossess notices to take their cases to court, where attorneys would do their best to gum up the system and force delays, thus staving off evictions. They also intended to arrange for families that were ousted to be taken in by neighbors in the same building, thus blunting the effect of the eviction.19

What started out as another grass-roots movement of housewives, however, was quickly taken over by the local branch of the Socialist Party, which was heavily Jewish and, of course, male. Tenants of individual buildings were encouraged to negotiate together, but no women’s umbrella association emerged this time, or needed to. A male-dominated “Anti-High Rent Bureau” set up within the Socialist Party managed everything, and as a result this strike was well organized from the beginning. There was canvassing and leafleting, there were mass meetings, and there was outreach to the labor unions.

Volunteers educated local women on how to present offending landlords with several strong arguments against evicting tenants. They were told to point out that it cost eight dollars to evict one family versus twelve dollars to reduce a family’s rent for a year by a dollar a month. And to warn landlords that the Socialist Party would see to it that no one would rent the vacant rooms.

If that didn’t work, they could threaten to report the landlord to the authorities. The Tenement House Act had mandated so many improvements that violations could be found in almost any building, and a citation by the Tenement House Commission was essentially a lien on a property. If the landlord could be made to see that his best option was simply to lower rents, he would be asked to sign an agreement committing to do it for a specified period of time—that is, a lease.20

There were tussles with the police, who broke up open-air meetings held without permits, and who had no choice but to get involved when crowds interfered with marshals carrying out evictions. But by New Year’s Eve, some fifty thousand tenants had signed on, and within the first few days of 1908 the strike had spread to Brooklyn, Harlem, and Newark. The papers began to print news of landlords who capitulated and initialed rent-lowering agreements. Some were willing to deal, provided their tenants kept mum about the agreements. But others were more recalcitrant and set up a fund to fight the strikers, or hired thugs to assault nonpayers.21

Past East Side uprisings had, without exception, been the work of obscure women with no claim to fame, who had stood up for themselves and their community when conditions became intolerable, and then faded from public view when their ends had been accomplished. But the 1908 rent strike was notable for the support of a prominent New York power couple who were, and would remain, very much in the public eye: Rose Pastor Stokes, a well-known Yidishes Tageblatt columnist, socialist activist, settlement worker, and feminist, and her millionaire Episcopalian husband, James G. Phelps Stokes.

The couple had gained notoriety because of his social status and philanthropy and her activism, not to mention their divergent backgrounds. They visited the strikers’ headquarters on January 4 to pledge support, and Rose spoke at several meetings after that. “Rents on the East Side are exorbitant,” she told one crowd in a mixture of English and Yiddish. “Two dollars is not enough reduction. Five dollars is a more suitable amount. Stick to your principles and you will win in the end, but be orderly,” she exhorted her audience.22

The strike reached its crescendo in the second week of January, when some six thousand people were about to be turned out into the streets for nonpayment of rent. Many landlords believed that if this happened, others would capitulate and simply pay what was demanded of them. But the courts moved slowly, and while some tenants gave in or packed up and moved, many landlords came to terms to save the costs of eviction. The Socialists estimated that some 40 percent of the landlords in those tenements they had helped organize had offered rent reductions. And by the middle of January the strike had wound down.23

In both 1904 and 1908 the lessons of the 1902 meat boycott had not been wasted on the striking tenants. By organizing early, going house to house to secure grassroots cooperation, and allying with others, they had achieved their objectives with little if any bloodshed. And like the Ladies’ Anti-Beef Trust Association before it, the ad hoc vehicles they organized to reach their goals soon faded into history.