Chapter Nine

The Death of the Death

Penalty: The History

of Capital Punishment

in Minnesota

Learning Objectives

- Explain the consequentialist and retributivist perspectives on punishment

- Articulate arguments for and against capital punishment

- Describe public sentiment in the United States regarding the death penalty

- Summarize key court cases relating to the imposition of the death penalty

- Explain the history of capital punishment in Minnesota, including the first and last executions

- Explain the circumstances surrounding the federal government's mass execution of 38 Sioux Indians in Mankato, Minnesota, in 1862

- Identify elements of 1st degree murder under Minnesota statutes

- Identify the objectives of criminal sentencing according to the federal Sentencing Reform Act of 1984

- Describe the use of sentencing guidelines in Minnesota

Criminal justice as an academic and applied field of inquiry and practice is replete with controversial topics. Issues regarding race, fairness, equity, vengeance, and others regularly surface in criminal justice. One particular criminal justice issue, embodying all the above, has served more than most to represent all that is controversial and contested in criminal justice and criminology over the past several years. That issue is capital punishment.

About the Death Penalty

Capital punishment refers to the imposition of a sentence of death by execution for the proscribed crimes deemed to be so heinous as to warrant no less a penalty. In 2012, a total of 58 countries around the world still utilized capital punishment for certain offenses; 140 countries had abolished the death penalty (Amnesty International, 2013). Interestingly, the United States is the only western country to still have capital punishment.

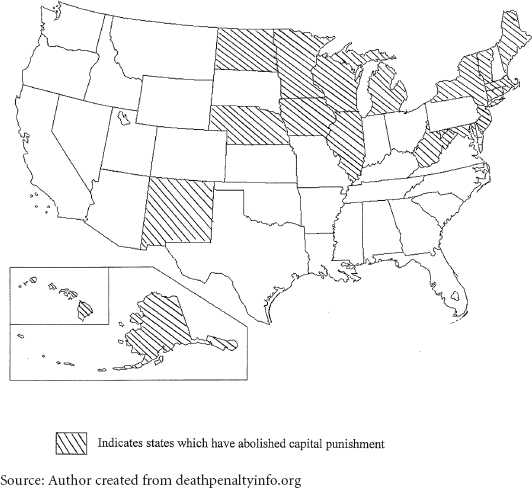

Of course, in the United States, the individual states are sovereign. Some states have capital punishment as their maximum penalty, while others do not. As of 2015, 19 states had abolished the death penalty, leaving 31 states with capital punishment in place. The State of Minnesota is one of the 19 states without the death penalty, having abolished it in 1911. Among the 31 states with the death penalty, several have placed moratoriums on the imposition and carrying out of the death penalty while matters regarding errors in convictions, inequalities in sentencing, and problems with lethal injection methods are examined and sorted out. The primary mechanism of execution is lethal injection, although some states have alternative methods available. In 2015, a law was passed in Utah reinstating the use of firing squads as a method of execution if lethal injection drugs cease to be available (McCombs, 2015).

The fact that two-thirds of the states still permit the use of capital punishment for their most serious and vicious offenders is reflective of the views of the American people on the whole. Approximately 63% of Americans favor the death penalty as an appropriate state response to some offenses. This margin of support has held steady for several years throughout the 2000s, but represents a decline from a peak of 80% support in the early 1990s (Saad, 2013).

Despite the popularity of the death penalty, and despite its availability as an option for punishing murderers, it is a punishment that is rarely imposed. In 2014, there were only 35 executions in the United States. In 2013, there were 39 (Death Penalty Information Center, 2015a). However, there are over 3,000 people on death row and there are many thousands of homicides committed in the United States each year. Americans like the idea of offenders paying the ultimate price for brutally killing others, but have not really mustered the political pressure to force legislators and government officials to actually impose this penalty with any urgency or consistency. In fact, the death penalty is only sought in 1% of capital murder cases (Armour & Umbreit, 2012).

Figure 9.1. States Without the Death Penalty

Arguments For and Against the Death Penalty

There are several arguments for and against the death penalty which are compelling. Generally, the arguments for the death penalty tend to be either consequentialist or retributivist. The consequentialist arguments focus on the utility of the death penalty. For example, if the death penalty has a deterrent effect and therefore results in fewer homicides, this is a positive consequence of that punishment. Additionally, if the death penalty at a minimum has an incapacitation effect (those put to death have been incapacitated from doing further harm), this too would be a positive outcome. Consequentialist, or utilitarian, arguments of punishment are associated with philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham from 18th to 19th century England. Bentham emphasized that punishment should be parsimonious, i.e., the idea that no more punishment than necessary to gain compliance by offenders with the rules should be employed. In

other words, the least severe punishment should be imposed which still meets social purposes. Bentham also said that society should take into account the offender's sensibilities when meting out punishment; in other words, punishment should be tailored to the offender. This approach has served as the primary rationale for indeterminate sentencing in the 20th century (Tonry, 2011).

Interestingly, opponents of the death penalty also tend to rely on consequentialist arguments. They note that the death penalty does not have a deterrent effect (and therefore has no societal gain in that regard). However, the death penalty does have costs (expensive to navigate due to multiple appeals, the potential for unfair application, no opportunity for rehabilitation, maintaining death row units, etc.) which arguably result in a societal net loss. They also point to the principle of parsimony and argue that legitimate goals of punishment can be accomplished with non-lethal penalties. Hence, opponents of the capital punishment say we need to look in other directions for society's response to heinous crimes.

The retributivist argument for capital punishment has little concern for consequences—positive or negative—of the death penalty. Retributivist philosophies espoused by the likes of Immanuel Kant and George Hegel suggest that punishment is appropriate for punishment's sake. Punishment, including the maximum punishment of death for some offenses, is proper because it is the just and proportionate thing to do. Retributivists note that utilitarian opponents of capital punishment show an amoral approach to punishment and fail to view the convicted offender as a rational human being, thereby denying him human dignity.

In fact, C.S. Lewis once penned an essay against the “humanitarian theory of punishment.” Humanitarian justifications for punishment focus on society's gain through an offender's involuntary rehabilitation. Lewis stated that this approach to addressing crime, including as applied to the abolition of the death penalty, does several things (Lewis, 1949):

1) it removes the concepts of moral culpability and proportionality from punishment;

2) it treats offenders like children, imbeciles, or animals, rather than morally autonomous adults;

3) it risks injustices predicated on well-meaning and tyrannical motives; and

4) it necessarily authorizes the punishment of the innocent (for their own good).

As Hegel noted, the humanity of an offender, and the rational choices he or she makes which result in “wrongs”, require “cancellation.” In some cases, the maximum penalty is the only sufficient penalty to cancel a wrong brought

about by an offender. Respect for the moral autonomy of the criminal and his or her capacity for making moral choices require punishment apportioned to the crime (Tonry, 2011).

The Risk of Error

One concern many opponents offer regarding capital punishment is that there is often a risk of the penalty being applied mistakenly against someone who does not deserve it. The concern relates to all forms of criminal sanction, but time lost due to error is compensable; life lost is irreversible. Concern over errors in the application of the death penalty have given birth to advocacy and public interest groups such as the Innocence Project (see

Chapter Four

). The Innocence Project traces its beginnings back to the early 1990s when a couple of law professors from New York City set out to address the substantiated notion that many wrongful criminal convictions occur because of eyewitness testimony rooted in error or malice. The ramifications of faulty eyewitness testimony are most severe in murder and stranger-rape cases given the long prison terms, and in some cases death sentences, that attach to those convictions. The Innocence Project evaluates thousands of cases every year for faulty evidence, prosecutorial misconduct, and inadequate defense. To date in the United States, there have been 329 convicted individuals who have been exonerated on reexamined DNA evidence alone; intervention by the Innocence Project was directly responsible for over half of these exonerations (Innocence Project, 2015).

Some proponents of the death penalty would counter the concern over mistakes by reserving capital punishment for only the most certain of cases. Effectively, after such a reform were put in place, the death penalty would only be levied in “smoking gun cases.” A bank robber shoots and kills a teller and then is wounded and captured in an ensuring police shootout at the bank entrance. A registered pedophile's semen is found in a little girl's dead body on his property. A prison inmate is captured on video camera stabbing and killing a cafeteria worker before being wrestled to the ground by prison guards. In these cases, the reasonable doubt threshold has not only been met, but arguably so has proof beyond

all

doubt. Some reformers would reserve a swift and certain death penalty for these types of offenders under these types of circumstances. However, significant changes in the laws, and perhaps even the Constitution, would need to occur before such a system could be implemented.

Cruel and Unusual Punishment

One argument against capital punishment today is less about philosophy and more about legality. In particular, opponents point to the Eighth Amendment of

the U.S. Constitution and its prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. They argue that the bar for objectionable punishment has been lowered over time as society has matured and as the community of democratic nations around the world has rejected capital punishment and other harsh forms of retribution.

Through several court decisions over the years, the U.S. Supreme Court has essentially identified two manifestations of cruel and unusual punishment: barbaric punishments of the kind incompatible with a civilized society and punishments which are disproportionate to the crime (De Leon & Fowler, 2013). Opponents of the death penalty have used both criteria to argue in the courts against it. They have claimed that capital punishment in the modern age is barbarism. They have also claimed that capital punishment, in particular cases, was a disproportionate response to the crime given the circumstances known about the offender and other factors.

With regard to the argument that the death penalty, in and of itself, is barbaric, the Supreme Court has consistently rejected that notion. The Supreme Court first articulated with specificity what it understood cruel and unusual punishment to be in the case of

Wilkerson v. Utah

(1878). In the Court's decision, it noted that some forms of punishment which no longer existed in the United States or the civilized world, such as drawing and quartering, public dissecting, burning offenders alive, and disemboweling, were indeed cruel and unusual under the Constitution. However, Utah's use of the firing squad was not. The Supreme Court has acknowledged, however, that the death penalty has a potential for barbarism. In a case concerning the use of the electric chair (

In re Kemmler

, 1890), the Court said a legitimate method of execution must not involve anything other than what merely causes death. Further, death should be relatively instantaneous and not involve extended and unnecessary pain.

With regard to the principle that punishment must be proportionate to the crime, lest it be deemed cruel and unusual, the Supreme Court first insisted upon this in the case of

Weems v. U.S.

(1910). The principle of proportionality handed down in

Weems

was later incorporated into the Fourteenth Amendment and therefore applied to the states as a result of

Robinson v. California

(1962). Since then, the U.S. Supreme Court has found a number of crimes and circumstances for which the death penalty had been statutorily proscribed to be disproportionate, including:

-

Coker v. Georgia

(1977)—rape of an adult

-

Thompson v. Oklahoma

(1988)—15-year-old murderer

-

Atkins v. Virginia

(2002)—murderer who is intellectually impaired

-

Roper v. Simmons

(2005)—murderer under 18

-

Kennedy v. Louisiana

(2008)—rape of a child

Interestingly, in the case of

Roper v. Simmons

in which the Supreme Court barred under the Constitution the execution of anyone whose capital crimes were committed when the offender was under the age of 18, the Court cited “evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.” Many opponents of the death penalty recognize this as an opening of the door for the Court to someday abolish the death penalty altogether under the justification of evolving societal standards. Supporters of the death penalty respond that no institution of government better represents the true pulse of society than democratically elected state legislators who are responsible for passing laws relating to the use or abolition of capital punishment. They note that if societal standards of decency on this subject do evolve in the direction of abolition, the legislative process will reflect it. Until then, they say, the Court should butt out.

Death Penalty as a Deterrent?

The utilitarian arguments against the death penalty that it is not a deterrent and that it is discriminatory against minorities is still an open debate. In 2000, University of Maryland criminologist Raymond Paternoster conducted a study of the potential for racially discriminatory death sentence practices. He found a significant difference in the sentencing patterns of convicted white murderers from that of convicted black murderers. In particular, he found that black defendants who murdered white victims were more likely to be charged with capital murder and sentenced to death than with any other racial combination of offenders and victims (Paternoster & Brame, 2003).

However, in 2005, statistician and sociologist Richard Beck of the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues, re-examined the data from the Paternoster and Brame study. Beck found that race played either no role or a small and unidentifiable role in death sentences. If race did play a role, it was in the other direction than identified by Paternoster and Brame, as Beck found that cases with a black defendant and a white victim were less likely to result in a death sentence (Berk, Li, & Hickman, 2005).

David Muhlhausen (2007) identified several longitudinal studies which have shown that capital punishment does have a deterrent against future murders. One study of capital punishment in Georgia by Emory University economists found that each execution resulted in 18 fewer homicides (Muhlhausen, 2007). Another study, by Emory University law professor Joanna Shepherd (2004) found that:

1) each execution was associated with three fewer murders;

2) each execution was associated with fewer murders of blacks, followed by whites, over other racial groups; and (importantly) ...

3) shorter periods of time on death row before execution was associated with an increased deterrent effect—for each 2.75 year reduction in time on death row, one murder was deterred.

Certainly, many social scientists would take issue with the findings in these and other studies which support the notion that an efficacious death penalty deters homicidal violence. It is safe to say at the very least that the consequences of the death penalty are not settled science.

History of the Death Penalty in Minnesota

For the first half-century following Minnesota's statehood, premeditated murder was punishable by death in the state. Minnesota was created as a territory in 1849, and officially became a state in 1858. According to the Death Penalty Information Center, Minnesota executed 27 people from 1860 until 1906; the method of execution in Minnesota was death by hanging.

Ann Bilansky

The first hanging in the state of Minnesota was that of St. Paul resident Ann Bilansky in 1860. Bilansky was also the only woman every executed in Minnesota. Bilansky was involved in a love triangle between herself, her husband Stanislaus Bilansky, and her lover John Walker. On March 11, 1859, Stanislaus Bilansky died after a 9-day illness. The next day, March 12, Stanislaus was placed in a coffin for visitation and a funeral to follow. Several friends and family members gathered at the Bilansky house in St. Paul to pay their last respects, along with John Walker who did carpenter work for Bilansky's. However, before the funeral procession to the cemetery could commence, the Ramsey County coroner, John Wren, showed up at the Bilansky home with three doctors, a coroner's jury, and witnesses in tow (Trenerry, 1985). The doctors examined the body and the coroner held an inquest right there, calling witnesses to testify. It was determined that Bilansky had died of natural causes from the illness he came down with on March 2, but that Ann's care for him during the illness was wanting—especially since she never called for a doctor. The funeral then was allowed to proceed.

Immediately following the funeral, Ann, John Walker, and Bilansky's house servant, Rosa Scharf, returned to the Bilansky home. Scharf observed that Walker apparently had no intention of leaving; indeed, later that evening, Scharf observed Ann undress in front of Walker. It was widely rumored among Bilansky friends that Ann and Walker had some sort of relationship. Walker had

actually facilitated Ann meeting Stanislaus in 1858, culminating in the Bilansky marriage in May of that year. Walker had referred to Ann as his aunt, but it was clear there was amorous affection between them. It was also well known that Stanislaus was an unpleasant and abusive person. It was unclear why Ann, who was charming, attractive, and already a widow from a previous marriage would agree to marry Stanislaus. By the time Stanislaus Bilansky had taken ill, he had complained many times to his saloon friends about Walker's apparent relationship with Ann. And Ann had done little to conceal how she felt about Stanislaus, telling others that she hated him and would not sleep with him (Trenerry, 1985).

By March 13, Ann Bilansky and John Walker were under suspicion of murder. On March 14th, an autopsy was ordered for Stanislaus. The exam revealed that his stomach and intestinal track was inflamed, and that his tongue was brownish and cracked. The doctor performing the autopsy later testified that this was consistent with arsenic poisoning. Additional testimony from one of Ann's friends indicated that she and Ann had gone shopping in late February, and that Ann had purchased arsenic for poisoning rats. The drug store clerk tried to sell Ann something that purportedly worked even better on rats, but Ann insisted that it must be arsenic.

Ultimately, Ann Bilansky was charged and tried for the murder of her husband based on a significant pile of circumstantial evidence. On June 3, 1859, the jury reached and delivered a verdict of “guilty.” At that time in Minnesota, the automatic penalty for premeditated murder was death. Later, in 1868, the Minnesota legislature changed the law to require an affirmative choice by juries to sentence a convicted murderer to death. That modification to the law remained in place for 15 years before reverting back to the mandatory death penalty for 1st degree murder (Armour & Umbreit, 2012).

Immediately after the death sentence was handed down, political pressure began to mount for the governor to commute her sentence. Many around the state, including those who believed she was guilty, did not abide with the idea of imposing the maximum penalty on a woman. In fact, the very day that the Minnesota Supreme Court upheld her conviction upon appeal, Justice Charles Flandrau wrote Governor Henry Sibley asking that he commute the sentence of Bilansky. He wrote (Trenerry, 1985, p. 38):

It is my firm conviction that a strict adherence to the penal code will have a salutary influence in checking crime in the State, but it rather shocks my private sense of humanity to commence by inflicting the extreme penalty on a woman. I believe she was guilty, but nevertheless hope that if you can consistently with your view of justice and

duty, you will commute the sentence which will be pronounced, to imprisonment.

Governor Sibley took no action as his term in office was about to expire.

On January 1, 1860, Alexander Ramsey became Governor of Minnesota. While considerable debate and hand-wringing took place among the governor's advisors and in the legislature regarding the propriety of the death penalty for women, and also for men, Governor Ramsey eventually issued the death warrant to the Ramsey County Sheriff, instructing him to carry out the sentence. On March 23, 1860, Ann Bilansky was hung just after 10 a.m. The anti-death penalty movement in Minnesota was born (Armour & Umbreit, 2012).

Mass Hanging of 38 Sioux Indians

Despite Minnesota's modern association with antipathy for the death penalty, the state ironically was the stage for the largest mass execution in U.S. history. This too happened in close proximity to the state's founding. The largest mass execution ever to take place in the United States was the hanging of 38 Sioux Indian combatants in Mankato, on December 26, 1862. However, in fairness, the State of Minnesota, per se, was not responsible for the mass execution; the federal government was.

On August 17, 1862, four Sioux Indians raided two farmhouses in Acton Township, located in the south-central part of the state, killing five white settlers there. The raid on the farm houses culminated in part from desperation Sioux Indians had felt due to the failure to honor commitments by the federal government and particularly local government officials. Reportedly a couple days previous, on August 15, negotiations between hungry Indians, governmental officials, and traders broke down when trader Andrew Myrick said of the Indians, “So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung.”

Word of the attack against the settlers made its way to the Lower Sioux Reservation near present day Morton, along the Minnesota River Valley. A decision was made among tribal members to preemptively go to war with the white settlers as reprisals would certainly follow after the Acton killings. The following day, on August 18, 1862, the U.S.-Dakota War began as bands of Sioux Indians attacked white settlers at their farmsteads and in small towns along the Minnesota River Valley. White men, women, and children were massacred in droves. In some documented accounts, Sioux warriors became drunk and made sport out of the killing of the settler children. Many women and teenage girls were reported to have been raped. On the other hand, many women and children were taken into captivity rather than murdered. It signaled the varied approaches of

the many Sioux bands and tribes to the conflict. The town of New Ulm, where hundreds of area settlers fled to, was placed under siege by the Indians and much of the town burned before the Indians were pushed back.

Governor Ramsey pled with the Abraham Lincoln administration, somewhat busy with the U.S. Civil War at the time, to make available thousands of troops and munitions. He noted that panic in the region had depopulated entire counties, and that a battle front had been drawn by the Indians extending 200 miles (Nichols, 2012). Initially, President Lincoln dispatched General John Pope to Minnesota to lead a newly created “War Department of the Northwest” which consisted of several army regiments. But initially the regiments were slow to muster. Pope made urgent requests to the War Department for more troops.

Pope wrote in his request for more soldiers (as cited in Nichols, 2012, p. 88):

You have no idea of the wide, universal and uncontrollable panic everywhere in this country. Over 500 people have been murdered in Minnesota alone and 300 women and children now in captivity. The most horrible massacres have been committed; children nailed alive to trees and houses, women violated and then disemboweled—everything that horrible ingenuity could devise. It will require a large force and much time to prevent everybody leaving the country, such is the condition of things.

Eventually, Pope received the troops he needed. The Sioux uprising lasted for six weeks before federal troops and state militia finally defeated the Indians.

After the surrender of the Indians, thousands of Sioux men, women, and children were rounded up, and 303 Sioux braves were charged and tried by military tribunals for what would be termed war crimes today and were sentenced to death. Both General Pope and Governor Ramsey were eager to impose this sentence as the cry for vengeance among whites in Minnesota was deafening. There was real concern that the rule of law could break down if the government did not adequately assuage the anger of Minnesotans. There was also concern that soldiers themselves holding hundreds of Indian men, women, and children might act out in vengeance against their non-combatant prisoners if the condemned 303 were not put to death. President Lincoln was very reluctant to execute so many people and to orphan so many children. It was not that atrocities were not committed by the Indians against settlers; they most certainly were. But in every case, was it these 303 Indians who committed them?

Lincoln decided to take a closer look at the trial records of the condemned Indians. He found that many appeared to be convicted on very flimsy testimony

and in some cases, only because they were present or in the vicinity when other braves committed the criminal acts. In the end, Lincoln found middle ground. He wrote, in response to a Senate resolution sponsored by the Minnesota delegation urging that the death sentences be carried out (as cited in Nichols, 2012, p. 112):

Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on the one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, I ordered a careful examination of the records of the trials to be made, in view of first ordering the execution of such as had been proved guilty of violating females.

As a result of that review, Lincoln ordered that 39 particular Indians be executed on December 19. Later, the date was extended to December 26. Just prior to the execution date, one of the 39 was pardoned in light of additional evidence. The remaining 38 Sioux Indians were executed by hanging on December 26th at 10 a.m. A large crowd gathered and observed the executions, but did not resort to lynch-mob violence against other Indians being held. It later came to light that one of the Indians executed was not a person against whom a death sentence had been ordered, but was included in the group by mistake (Nichols, 2012).

The execution of the 38 Sioux Indians has become a cause célèbre for Native Americans in Minnesota and the Upper Midwest. There have been parks created, commemorative bike runs, annual pow wows, and other events to foster “reconciliation” between Indians and whites which have emerged—especially in Mankato and other parts of southern Minnesota—to honor the 38 who were hung. These 38 have come to represent all the injustice that many Sioux Indians have experienced in Minnesota since the United States government established it as a territory. Often lost in the discussion is that, at the very least, most of these Indians certainly were guilty of war atrocities against unarmed women and children. Many Minnesotans today with ancestral ties to the settlers who endured or succumbed to the Sioux uprising wonder if these 38 who were hung most appropriately epitomize government injustice against Native Americans. They note that reconciliation goes both ways, or at least it should.

William Williams

The execution to end all executions in Minnesota was that of William Williams in 1906. On April 15, 1905, at approximately 1:00 a.m., gun shots were heard by Emma Kline while she lay in bed in her St. Paul apartment. Moments later, William “Bill” Williams knocked on Kline's apartment door. When she answered,

she recognized the man to be Williams, who was an occasional visitor to the Kellers in the apartment upstairs. He told her that the Mrs. Keller and her son had been shot and that she should go upstairs to tend to them. When Kline arrived upstairs, she found Mary Keller was shot and sitting in a chair. Mary told Kline that “Bill shot my boy and nearly killed me too” (Trenerry, 1985). She then asked Kline to check and see if her boy was dead. Kline found Johnny Keller in his bed with two gunshots to the head. He was still breathing, but later succumbed to his wounds, as did his mother Mary.

After Williams had instructed Emma Kline to check on the Kellers, he had gone directly to the St. Paul central police station and told officers there that he had shot the Kellers after an argument with Mary. He said he had left the revolver there in the Keller apartment. Williams was placed under arrest while police officers checked on the Kellers. At the apartment, they found the two victims, mortally wounded, and the revolver.

During Williams' trial, doctors testified about the nature of the wounds to Johnny Keller. They noted that he had been shot from close range to the back of the head while he was in bed. Johnny had been coldly executed. The jury also heard the testimony of Emma Kline and the police account of Williams' confession. Also introduced into evidence were several letters written by Williams to Johnny Keller which helped paint the motive. It turned out that Williams had a homosexual relationship with Johnny. He wanted Johnny to leave with him that night, but Johnny did not want to. Further, Johnny's parents forbad the relationship and wanted Williams to have no more contact with him. William was a lover scorned—scorned by the parents of his lover and the lover himself.

On May 19, 1905, the jury convicted Williams of 1st degree murder. The jury had had the option of convicting Williams instead of 2nd degree murder. In fact, during deliberations, the jury asked the judge if it would still be 1st degree murder if John Keller and Mary Keller had been shot after an argument and scuffle, but not with prior intent or planning to kill. The judge simply reread the charge regarding 1st degree and 2nd degree murder (Trenerry, 1985). Williams was immediately sentenced to death by hanging.

The execution took place on February 13, 1906, at 12:31 a.m. at the Ramsey County Jail in St. Paul. The execution took place after midnight because of the John Day Smith Law of 1889. This law required that executions take place at night and that journalists not be present. The rationale behind the law was that many previous executions had become rowdy public spectacles. Although executions in the state would always take place at night after the passage of the law, the ban against coverage by journalists was never enforced (Tanick, 2011).

When Williams was dropped from the gallows, he hit the ground. It turned out that the rope being used was several inches too long. Sheriff's deputies rushed in and hoisted Williams up by the neck by pulling on the rope. It was approximately 15 minutes before Williams was declared dead. The reporters there to cover the execution were uniformly horrified at what had happened. The next day, front page stories appeared in the paper about the botched hanging. Minnesotans had been growing queasy about capital punishment. There had been a vibrant anti-death penalty movement in Minnesota for decades. The news accounts of this hanging gone awry were the tipping point. Death penalty opponents convinced the legislature to abolish capital punishment five years later. In 1911, life imprisonment (with the possibility of parole) became the penalty for premeditated murder.

Resurgence of Interest in Capital Punishment in Minnesota

In the century since the abolition of the death penalty in Minnesota, there have been many attempts to bring it back. Most recently, in 2004, Governor Tim Pawlenty unsuccessfully lobbied for a referendum to consider the reinstatement of the death penalty in Minnesota. Critics of Pawlenty's proposal argued that the death penalty was too expensive, too unfair against the poor and minorities, and too often errant (in that innocent people are sentenced to death). Pawlenty said his proposal would mitigate against those concerns in very specific ways. His proposal included (Death Penalty Information Center, 2015b):

- a requirement that DNA evidence link a suspect to the crime;

- it would apply only to 1st degree murder of 2 or more persons, or a public safety official, or involving a sexual assault or other heinous or cruel actions;

- require unanimous jury decision;

- county attorney's decision to pursue death penalty would have to be confirmed by peer review of fellow prosecutors;

- Minnesota Supreme Court would automatically review all death sentences;

- clemency board would be established which could urge the governor to grant a reprieve;

- death penalty would not be imposed on defendants under 18 or those found to be mentally disabled;

- would not apply when eyewitness testimony is by a jail informant;

- lethal injection would be the sole execution method.

Pawlenty's proposal was in 2004. Since then, the U.S. Supreme Court has already mandated some of the provisions Pawlenty offered to include, such as no death penalty for crimes committed by juveniles or the mentally impaired, and no death sentences by other than a unanimous jury. Since Pawlenty's effort, there has been no serious proposal in Minnesota to bring back capital punishment.

Punishment in Minnesota Today

While Minnesota does not have the death penalty, it does provide for severe sanctions for premeditated 1st degree murder. In 1911, the state made a life sentence the mandatory sentence for such offenders. However, there had always been the possibility of parole. Minnesotans, content with foregoing Governor Pawlenty's proposal and remaining a capital-punishment-free state in the mid-2000s, were not content with the prospect of violence and vicious 1st degree murderers ever roaming the streets of Minnesota. So, in 2005, the state legislature changed the law, assigning a mandatory penalty of life without the possibility of parole for 1st degree murderers. Murder in the 1st degree in Minnesota is defined as (Minnesota Statutes §609.185):

(1) causing the death of a human being with premeditation and with intent to effect the death of the person or of another;

(2) causing the death of a human being while committing or attempting to commit criminal sexual conduct in the first or second degree with force or violence, either upon or affecting the person or another;

(3) causing the death of a human being with intent to effect the death of the person or another, while committing or attempting to commit burglary, aggravated robbery, kidnapping, arson in the first or second degree, a drive-by shooting, tampering with a witness in the first degree, escape from custody, or any felony violation of chapter 152 involving the unlawful sale of a controlled substance;

(4) causing the death of a peace officer, prosecuting attorney, judge, or a guard employed at a Minnesota state or local correctional facility, with intent to effect the death of that person or another, while the person is engaged in the performance of official duties;

(5) causing the death of a minor while committing child abuse, when the perpetrator has engaged in a past pattern of child abuse upon a child and the death occurs under circumstances manifesting an extreme indifference to human life;

(6) causing the death of a human being while committing domestic abuse, when the perpetrator has engaged in a past pattern of domestic

abuse upon the victim or upon another family or household member and the death occurs under circumstances manifesting an extreme indifference to human life; or

(7) causing the death of a human being while committing, conspiring to commit, or attempting to commit a felony crime to further terrorism and the death occurs under circumstances manifesting an extreme indifference to human life.

A charge of 1st degree murder requires an indictment by a grand jury.

Life without the possibility of parole has also been extended as a penalty to certain 1st degree criminal sexual conduct (involving sexual penetration) and 2nd degree criminal sexual conduct (involving sexual contact but not penetration) offenders if two or more heinous elements are present in the offense, or if one heinous element is present and the assailant is a repeat offender. Heinous elements include conduct such as torture, mutilation, and other forms of extreme violence and depravity. As of 2012, there were 569 prisoners serving life-terms in Minnesota (Armour & Umbreit, 2012).

The federal Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 articulates a number of sentencing objectives that have guided sentencing judges around the country in their leniency or harshness toward convicted defendants. Some of the more important objectives of sentencing are (Champion, 2008):

- to promote respect for the law;

- to reflect the seriousness of the offense;

- to provide just punishment for the offense;

- to deter the defendant from future crime;

- to protect the public from the convicted offender; and

- to provide the convicted offender with educational/vocational training or other rehabilitative assistance.

These goals of sentencing have not only guided judges but state legislatures in their effort to craft effective and appropriate sentencing schemes. What is interesting about the objectives is that all but the last one implies or implores the use of harsher sentences against criminal offenders. Certainly, by the mid-1980s when the Sentencing Reform Act had passed, the need for stronger penalties was broadly subscribed to in American society and in Minnesota.

In fact, even before the federal Sentencing Reform Act of 1984, Minnesota had already begun to move toward a tougher stand against criminal offenders by limiting the use of indeterminate sentencing (which allows correctional officials and judges to release offenders from prison when they were deemed to be rehabilitated rather than after having served a set minimum sentence). In

1980, Minnesota adopted the use of a sentencing guideline grid. Minnesota was the first state in the Union to adopt sentencing guidelines (Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission, 2015). Since then, the laws in Minnesota have been further honed to result in longer prison sentences for various types of criminal offenders.

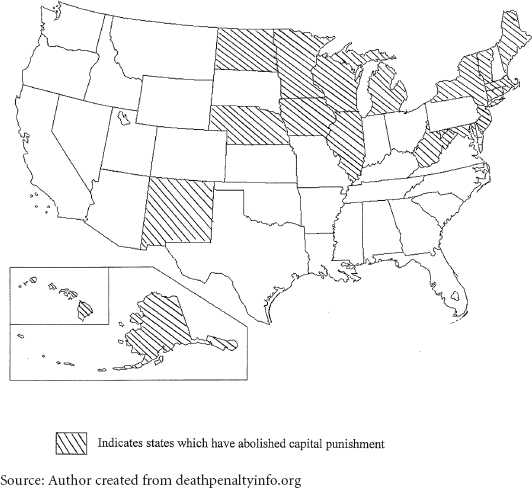

Minnesota's guidelines-based grid sentencing is a form of presumptive sentencing. With this form of sentencing, a specific sentence for an offender appears in a grid and is expressed as a range of months for each and every offense or offense class. The sentences prescribed in the sentencing grid are expected to be imposed in all but exceptional cases where there are aggravating or mitigating circumstances. Usually sentencing grids, such as the one used by Minnesota, have the current offense under consideration listed on the vertical axis and the prior criminal record of the offender on the horizontal axis. The point where these two intersect is the sentencing range. The number of months listed below the range is the presumptive sentence. However, a judge can sentence someone to any amount within the range without justification. A judge may depart from the range in a higher or lower direction depending on aggravating or mitigating circumstances, respectively. These are called upward and downward departures and they require the judge's written explanation justifying the departure.

In 2014, Minnesota joined 28 other states and passed legislation to compensate individuals wrongfully convicted of a crime and who served time in prison. Minnesota Statutes §590.11 describes the elements necessary for an individual to file a claim. The statute requires a prosecutor to join the petition for compensation in the interest of justice. It further requires of exonerees (Minnesota Statutes §590.11):

- they were convicted of a felony and served any part of the imposed sentence in prison;

- in cases where they were convicted of multiple charges arising out of the same behavioral incident, they were exonerated for all of those charges;

- they did not commit or induce another person to commit perjury or fabricate evidence to cause or bring about the conviction; and

- they were not serving a prison term for another crime at the same time.

Those receiving compensation under this law may receive between $50,000 and $100,000 for each year of wrongful incarceration, and $25,000 to $50,000 for each year wrongfully placed on supervised release.

Figure 9.2. Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Grid

Federal Death Penalty

Although Minnesota does not have capital punishment, there is always the possibility that a criminal offense committed in Minnesota will result in a death

sentence. This is because federal criminal law applies in the State of Minnesota as it does throughout the country, and there are several federal offenses for which the death penalty could be imposed.

The case of the murder of Dru Sjodin exemplifies this point. On November 22, 2003, in the late afternoon, University of North Dakota college student Dru Sjodin was kidnapped from a Grand Forks, North Dakota mall parking lot; she had just ended her work shift at a store inside the mall. A week later, police arrested Alfonso Rodriguez, Jr. in connection with Sjodin's disappearance. Rodriguez was a 50-year-old, registered Level III sex offender. Those labeled “Level III” are sex offenders deemed most likely to reoffend. The police had been able to connect Rodriguez to the mall and items of Sjodin's to Rodriguez' car. In April of 2004, once the snow drifts began to melt, Sjodin's body, with her hands tied behind her back, was found just west of Crookston, Minnesota. Crookston is located 25 miles to the east of Grand Forks, North Dakota, and was where Rodriguez was living with his mother. An autopsy showed that Sjodin had been raped, beaten, and stabbed and cut several times. Additional forensic evidence on the body linked Rodriguez to the crime.

The outrage over the crime by residents of both North Dakota and Minnesota was widespread and intense. Neither North Dakota nor Minnesota have the death penalty. However, because Sjodin was kidnapped in one state and brought across states lines to another, the federal government had concurrent jurisdiction. Rodriguez was charged under the federal kidnapping statute and was convicted in federal court in the District of North Dakota on September 22, 2006. Because the kidnapping resulted in death, Rodriguez was eligible for the death penalty. The federal jury, consisting of North Dakota citizens, recommended a death sentence—despite North Dakota not having a death penalty of its own. On February 8, 2007, Rodriguez was formally sentenced to death and sent to federal death row at the federal prison in Terre Haute, Indiana.

The same dynamic is played out with the Boston Marathon bombing trial of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who was the surviving member of a pair of brothers accused of detonating two pressure cooker bombs near the finish line of the Boston Marathon in 2013. Tsarnaev was tried in federal court in Boston and convicted on 30 counts relating to his terroristic acts. All along, prosecutors indicated their intention to pursue the death penalty despite the state of Massachusetts having no such penalty of its own. Jurors were selected in part because of their willingness to consider the death penalty. The support for seeking the death penalty for Tsarnaev was generally popular in the Boston area and throughout New England. On May 15, 2015, the federal jury of seven women and five men unanimously determined that Tsarnaev should die for his crimes. The

sentence is another example of citizens sensing that the only appropriate and just penalty for certain heinous criminal acts is the penalty of death, despite those same citizens permitting their own state to forego such penalties as too costly and uncivilized. It is perhaps an unintended consequence, unforeseen by the framers, that one of the chief blessings of America's model of government—federalism—permits incongruity in criminal sentencing, even on matters as fundamental as life and death.

Over 100 years ago, Minnesota chose to abandon the death penalty as a punishment for the most heinous of offenders. Since then, the state has wrestled with questions concerning what punishments are most proper for violent offenders and other criminals. In an effort to minimize subjectivity and unfair or unjust variability in criminal sentencing, Minnesota was among the first states to adopt sentencing guidelines, presumptive sentencing, and mandatory sentences for certain types of offenses. However, some Minnesotans remain convinced that the death penalty is the only appropriate penalty for the most callous and scheming of homicidal offenders. The federal criminal justice system does provide a method for imposing the death penalty on certain offenders who may commit crimes in Minnesota which are simultaneous capital federal offenses. However, to date, no federal offenders have ever been handed a death sentence for crimes committed and prosecuted in Minnesota.

Key Terms

Ann Bilansky

Atkins v. Virginia

Capital Punishment

Coker v. Georgia

Consequentialist Theory

Death Penalty

Determinate Sentencing

Deterrence

Dru Sjodin

Exoneree Compensation

Federal Death Penalty

Kennedy v. Louisiana

Presumptive Sentence

Retributivist Theory

Robinson v. California

Roper v. Simmons

Sentencing Grid

Sentencing Guidelines

Sentencing Reform Act of 1984

U.S.-Dakota War

Weems v. U.S.

Wilkerson v. Utah

William Williams

Selected Internet Sites

Discussion Questions

- What are the strongest arguments for the death penalty? Against the death penalty?

- What is cruel and unusual punishment?

- In what ways do sentencing guidelines contribute to fairness and equality?

- Should politicians in Minnesota examine the reinstatement of the death penalty if the majority of Minnesotans want it?

- What should the state do for individuals who have been wrongfully convicted of a crime and later exonerated after serving a portion or all of a prison sentence?

- Should the federal government pursue the death penalty in capital cases which happen to take place in states that do not have the death penalty?

References

Amnesty International (2013).

Death sentences and executions 2012

. London, UK: Amnesty International Publications.

Armour, M. & Umbreit, M. (2012). Assessing the impact of the ultimate penal sanction on homicide survivors: A two state comparison.

Marquette Law Review, 96

, 1–131.

Atkins v. Virginia

, 536 U.S. 304 (2002).

Berk, R., Li, A., & Hickman, L. (2005). Statistical difficulties in determining the role of race in capital cases: A re-analysis of data from the state of Maryland.

Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 21

(4), 365–390.

Champion, D. (2008).

Probation, parole, and community corrections

. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Coker v. Georgia

, 433 U.S. 584 (1977)

De Leon, J. & Fowler, J. (2013). Cruel and unusual punishment. In J. Albanese (ed.)

Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice

. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

In re Kemmler

, 136 U.S. 436 (1890)

Kennedy v. Louisiana

, 554 U.S. 407 (2008)

Lewis, C.S. (1949). The humanitarian theory of punishment.

The Twentieth Century: An Australian Quarterly Review, 3

(3), 5–12.

Muhlhausen, D. (2007).

The death penalty deters crime and saves lives

. Testimony before the Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Property Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate. June 28, 2007.

Nichols, D. (2012).

Lincoln and the Indians: Civil war policy and politics

. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

Paternoster, R. & Brame, R. (2003).

An empirical analysis of Maryland's death sentence system with respect to the influence of race and legal jurisdiction

. Department of Criminology, University of Maryland.

Robinson v. California

, 370 U.S. 660 (1962)

Roper v. Simmons

, 543 U.S. 551 (2005)

Shepherd, J. (2004). Murders of passion, execution delays, and the deterrence of capital punishment.

Journal of Legal Studies, 58

(3), 791–846.

Tanick, M. (2011). Looking back: A century without executions.

Bench & Bar.

March 14.

Thompson v. Oklahoma

, 487 U.S. 815 (1988)

Tonry, M. (2011).

Why punish? How much?

Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Trenerry, W. (1985).

Murder in Minnesota

. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

Weems v. U.S.

, 217 U.S. 349 (1910)

Wilkerson v. Utah

, 99 U.S. 130 (1878)