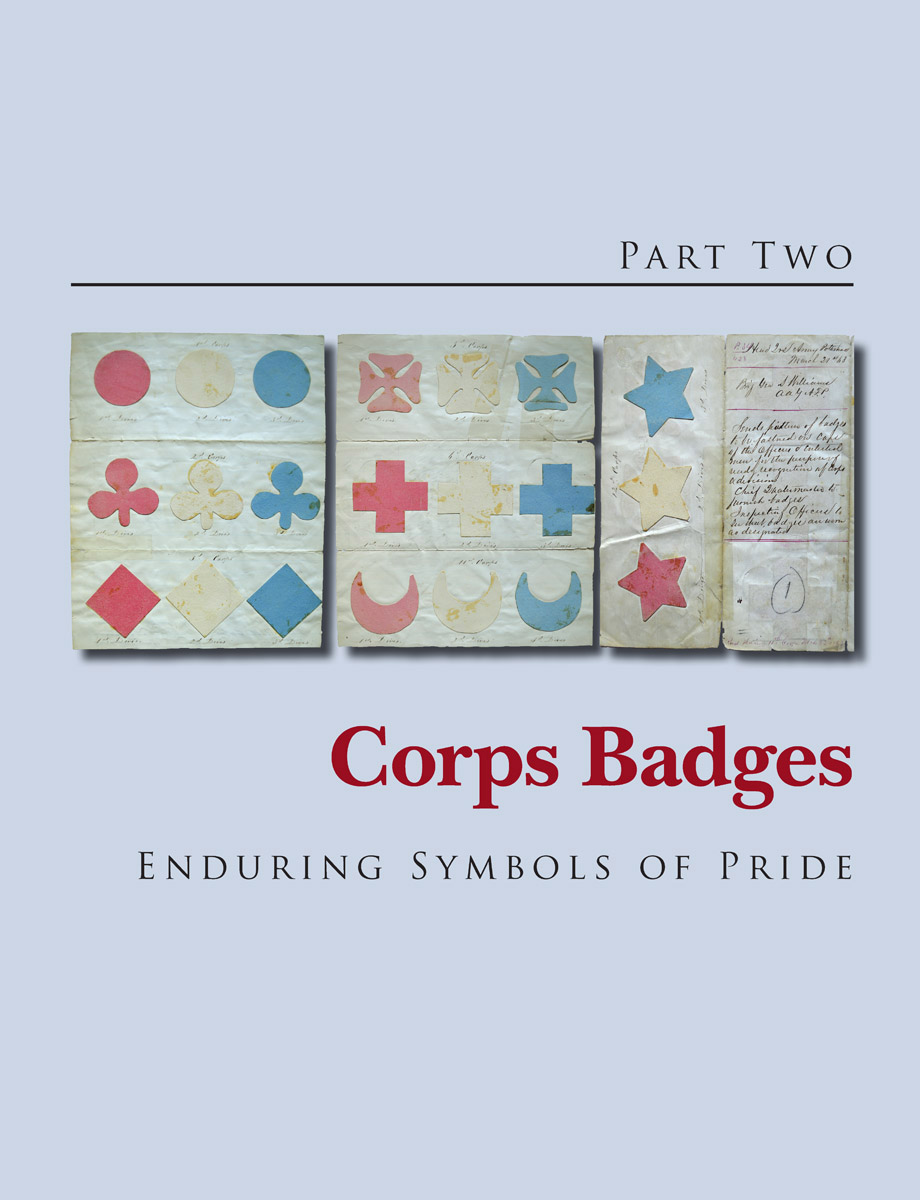

On March 21, 1863, the AAG of the Army of the Potomac sent copies of this order to each of the seven corps comprising the Army. This original document, with paper cutouts attached, shows the initial intended shape and color of each badge and was the true birth of this iconic tradition.1 CHRISTOPHER HEIZER PHOTO

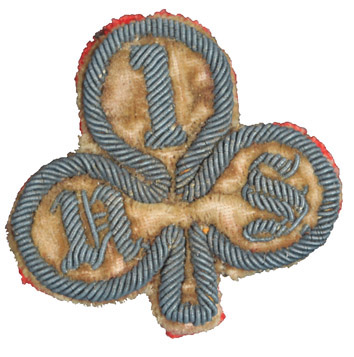

THE IDEA FOR ONE OF THE WAR’S MOST ENDURING INNOVATIONS CAN BE dated to June 28, 1862, when the following order was distributed to the 3rd Division, 3rd Corps:

Headquarters 3rd Div. 3rd Corps

June 28th, 1862

The General Comidg. Division directs that officers in command of Companies are to wear a piece of Red Flannel 2 inches square on the front of their caps. Field officers to wear the same upon the top of the cap—this to be done immediately that they may be recognized in action.

By order of Genl. Kearney2

General Kearney had served in the Regular Army during the Mexican War, and had lately traveled abroad and served as a cavalry officer in the French Army during the Italian War. He had combat experience and was certainly aware of how important it was to be able to quickly identify troops in the confusion of battle. Before he could expand on his idea, he was killed in the engagement at Chantilly, Virginia, on September 1, 1862. In his honor both officers and men of his division continued to wear the “Red Patch.”

By this time, except for units wearing special uniforms, it had become difficult, if not impossible, for commanders in the field to readily identify the assigned unit to which a soldier might belong or to quickly recognize the parent organization of a regiment. Prior to the war the brass numbers, letters, and branch insignia worn by the Regular Army on their headgear clearly showed the parent unit of each soldier.3 This was fine when the army had only ten regiments of infantry, four mounted regiments, and four of artillery, with a total of just over 16,000 officers and men. Now, with many thousands of men and hundreds of regiments, some means of ready identification was needed.

It would take a volunteer officer, Lieutenant Colonel J. Egbert Farnum of the 1st Regiment, Excelsior Brigade (70th New York Infantry) to call attention to Kearney’s idea by bringing it to his division commander, General Daniel Sickles.

Head Quarters 1st Regiment Ex. Brigade

Camp near Falmouth Va. Dec. 7th 1862

General:

I beg most respectfully to call your attention to an idea which I present for your consideration.

The Division recently commanded by the lamented Kearney, has a distinguishing mark for both officers and men, which is worn as an honorable distinction and which is prided as such, by both officers and men. I allude to the patch of red flannel.

It has presented itself to me; that were you to issue an order to your Division, allowing them to assume some such distinctive mark that it would, especially at a time when it is supposed that a general action is pending, meet with unanimous approbation, and the source of pride to you hereafter.

I have ventured to make this suggestion, because I think in the multiplicity of your official duties this slight subject might be overlooked.

Very truly & Respectfully

J. Egbert Farnum

Lt. Col. Commig. 1st Regt. Ex. Brig.

To Genl. Sickles4

The general action Lieutenant Colonel Farnum anticipated was the disastrous December 14 battle of Fredericksburg. However, it was not until the reorganization of the Army of the Potomac in March 1863 that the new army commander, General Joseph Hooker, took action to have designation insignia designed for each corps and division under his command.

Although credit has been given to his chief of staff, General Daniel Butterfield, for bringing forward the idea, it seems possible that it was General Sickles, now a corps commander, acting upon the idea presented to him by Lieutenant Colonel Farnum, who brought it to the attention of the army commander. General Butterfield was, however, assigned the task of designing the appropriate badges, which would be made of colored cloth and issued to the entire army.

These badges were to be affixed, along with the brass regimental number and company letter, to the hat or cap of each individual solder. The following order, which now took the concept beyond a single division to the corps level, can be considered the official birth of the famous corps badge itself.

Headquarters

Army of the Potomac

March 21st 1863

Circular

For the purpose of ready recognition of Corps and Divisions of this Army, and to prevent injustice by reports of straggling and misconduct through mistake as to their organizations, the Chief Quartermaster will furnish without delay the following badges to be worn by the officers and enlisted men of all the regiments of the various corps mentioned. They will be securely fastened upon the centre of the tops of the caps. The inspecting officer will at all inspections see that these badges are worn as designated. 1st Corps a Sphere, 2nd Corps a Trefoil, 3rd Corps a Lozenge, 5th Corps a Maltese cross, 6th Corps a Cross, 11th Corps a Crescent, 12th Corps a star.

Red for 1st Division, white for 2nd Division, blue for 3rd Division.

The sizes and colors will be according to a pattern (see next page).

This order was forwarded to General Rufus Ingalls, chief quartermaster of the Army of the Potomac, with instructions to furnish the required badges.

To assure a continuous supply of the badges, steel cookie-cutter-type cutting dies were produced in the shape of each badge. The order for these dies was sent to Colonel George Crosman at Schuylkill Arsenal on March 28. The first supply of colored cloth was sent on to the Army of the Potomac supply depot located at Falmouth, Virginia, on March 31, 1863, followed on April 6 by the cutting dies, mallets, and metal plates to use as cutting boards.6 These were then distributed to the various corps quartermasters. The badges would then be cut out and distributed to the various regiments at the brigade level.

This badge, combined with the brass numbers and letters, solved the problem, at least in part. By the time the army marched north toward Gettysburg, most of the regiments would have received the new badges.

It would take the remainder of the war before the practice would be adopted in each corps of the widely scattered Federal Army.7 While these badges eventually became a source of pride to the men who wore them, the initial issue was met with indifference by many, as the numerous orders demanding the wearing of the badge testify.

Sept. 22, 63

1st Brigade, 2nd Division 1st Corps

It has been observed that there is a great carelessness with many of the soldiers in wearing the prescribed badges. Some pin them on the side of the cap, and others fasten them in some other improper way, and some do not wear them at all. The Regimental Commanders are directed to give this matter their attention, and correct such abuses at once. The order requiring the badge to be worn directs that it be placed on the top of the cap, and that it be worn constantly.

By command; Col. Thomas F. McCoy Comd. Brigade8

139th Pa. Infantry H.Q. 139th P.V.

April 24, 1863

Notwithstanding the numerous orders, and all that has been said about “the cross” being sewed upon the caps of officers and men some are still without them, while many have them pinned or tacked on. If any man is found at dress parade tomorrow evening without the cross properly sewed upon his cap his immediate commander will be reported to the General Commanding the Brigade.

By Order

Col. F. H. Collier

4th Brigade, 1st Division, 2nd Corps

H.Q. 4th Brigade, Camp near Falmouth, May 21, 1863 General Orders No. 6 (part)

The badge prescribed by General Orders will be worn on the top of the cap, the figures distinguishing the Regiment below the badge, and the letter of the Company upon the badge, which latter must be neatly sewed on—when soiled or lost they will be at once replaced.

Sept. 13, 1863

Company Cmdrs. Will be held responsible that their men appear at Guard mount, inspection, Dress Parades, and all other military duty with their shoes cleaned and a Corps Badge on their caps or hats, any man appearing contrary to this order will be required to do police or fatigue duty for 3 days.

Col. M.D. Hardin9

Circular: 2nd Division 12th Corps June 16, 1863

The Division Quartermaster has now on hand a supply of white stars, the badge of this Division.

Requisitions will be at once made to supply deficiencies in this respect and any man of this command found after today, not wearing this badge as directed in existing orders, will be severely punished.

General John W. Geary

Brigade, 3rd Division, 6th Corps.

93rd Pa. Regimental letter and Order book

August 1, 1863

Circular:

Requisitions will be immediately made on the Brigade QM for the number of badges necessary to supply the wants of the officers and men in the respective regiments of this Command.

Attention is called to circular order of April 19, 1863 from these H.Q. pertaining to badges. It will be immediately and strictly enforced.

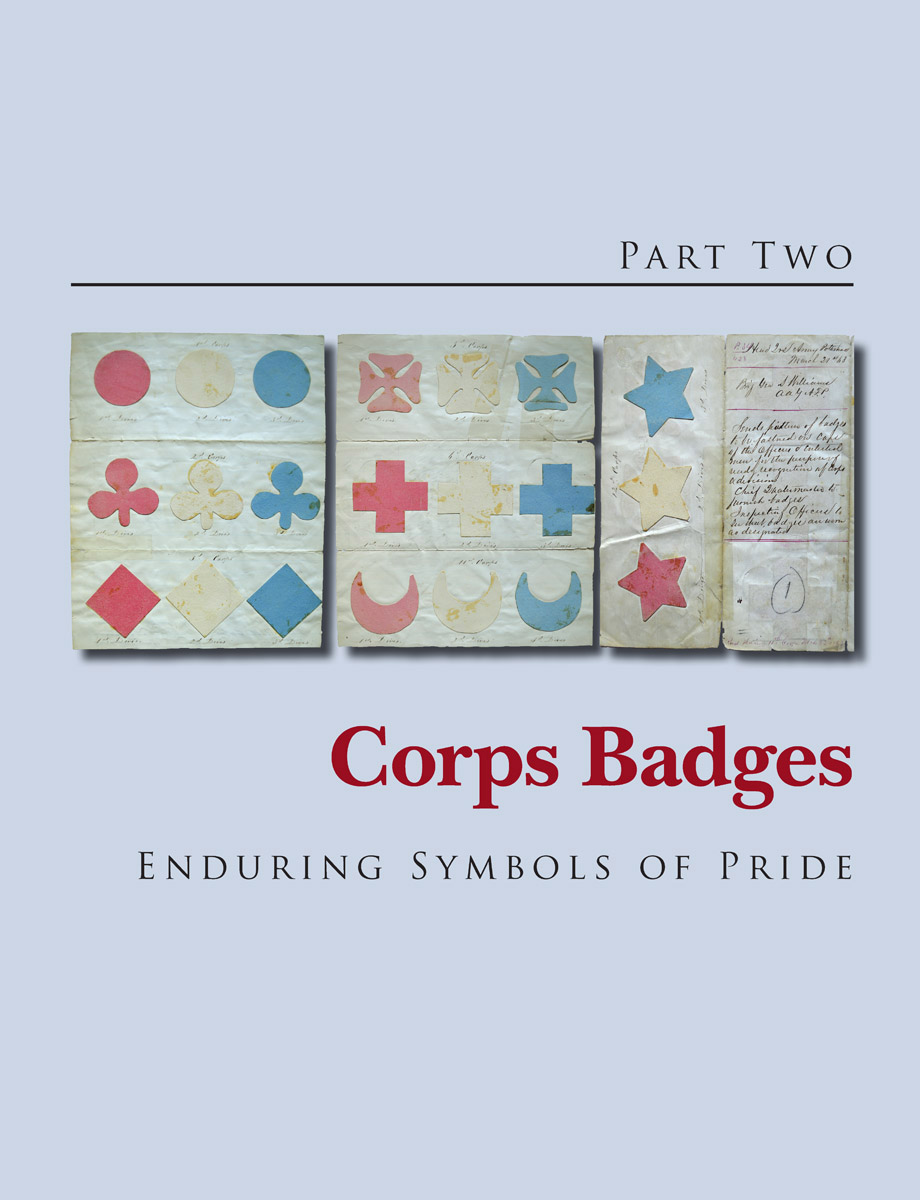

Handbill advertising army corps badges from the firm of H.G. Clagston in Philadelphia. Most likely dating from 1863, as many corps are not represented. Private goods dealers and jewelers nearly immediately provided a finer alternative to the die-cut issue badges, only equaled by the soldiers’ desire to have them. PRIVATE COLLECTION

Officers and enlisted men alike preferred the comfort and shelter provided by a wide-brimmed, soft felt hat like this example, worn by Captain Edward Stratton, 12th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry. Stratton was badly wounded in the knee during his unit’s first engagement at Chancellorsville, Virginia, which resulted in the amputation of his leg. The blue trefoil indicates the 12th was part of the 3rd Division of the 2nd Army Corps. C. PAUL LOANE COLLECTION

SHORTLY AFTER THEIR INITIAL ISSUE, A UNIQUE AND LITTLE-OKNOWN USE OF the corps badge was devised by the 12th Corps.

General Orders no. 13 Head Quarters 12th Army Corps

April 5, 1863

Commanding officers of Regiments will detach one private soldier from each Company under their command for the sole purpose of carrying off the wounded of their command to the ambulances. These men will wear a “Green Badge” on the left breast. Quartermasters will at once make requisition for the material to make the badges.10

This sumptuous, high-quality, enameled minié ball badge was apparently unique to the 1st Massachusetts Volunteers. Shown in period photos of officers, it was likely adopted during the first half of 1863. This example with battle honors and a silver 3rd Corps badge was worn by Brevet Major William L. Candler, who became an aide-de-camp to General Hooker. Candler was mentioned for gallant and meritorious service at Antietam and Chancellorsville. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

Green would again come into use as a standard badge to designate the 4th Division in a corps after consolidation expanded their size. In this case it would be worn as a standard corps badge.

Not until they were worn in combat and through the hardships of campaign did the corps badges take on a special significance in the hearts and minds of the Federal soldiers. In 1866 an Act of Congress recognized the unique meaning the badges had taken by authorizing all officers and enlisted men who had been honorably discharged, or were still on active duty, to wear the badge of their service organization on occasions of ceremony.11 Today they are represented on the regimental monuments that stand on the battlefields across our nation. They were, in fact, the forerunner of the designation patches worn by today’s Army and Marine Corps.

Corps badges quickly became a source of pride in the army. Shortly after the first cloth, die-cut versions were issued, enterprising companies and jewelers offered commercial varieties ranging from simple metal stampings to the most elaborate works of art that money could buy. Many soldiers availed themselves of these offerings, and even ordinary privates proudly sported some of these striking creations. The types and varieties of badges in use were endless. Worthy of a book in itself, here is a mere sampling of typical styles.

A silver mail agent’s badge of the 1st Brigade of the 2nd Division of the First Army Corps.

Officer’s cloth 1st Division of the 1st Army Corps badge with a bullion-embroidered border. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

A Clagston ribbed, stamped, commercial badge of the 2nd Division of the 1st Army Corps painted white.

Forage cap worn at the battle of Gettysburg by Private James Strauser of Company D of the 56th Pennsylvania Infantry. Strauser’s right leg was blown away by a shell during the first day’s fighting. In addition to the brass company and regimental insignia affixed to the crown, the spherical red cloth corps badge further displays his unit’s designation as part of the 1st Division of the 1st Corps. JAMES C. FRASCA COLLECTIONS

Corrugated tin canteen with cloth cover and a die-cut, first type, 1st Division, 2nd Army Corps badge attached to the side. This was used by a soldier of the 27th Connecticut Regiment who was mustered out shortly after the battle of Gettysburg. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

An early commercial form of the 2nd Corps badge consisting of a frame into which an appropriately colored piece of cloth could be inserted. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

Clagston stamped brass, 2nd Army Corps badge with red, white, and blue painted stripes indicating the wearer belonged to the corps staff. This illustrates well the evolution of this insignia from a club to a more stylish cloverleaf. PRIVATE COLLECTION

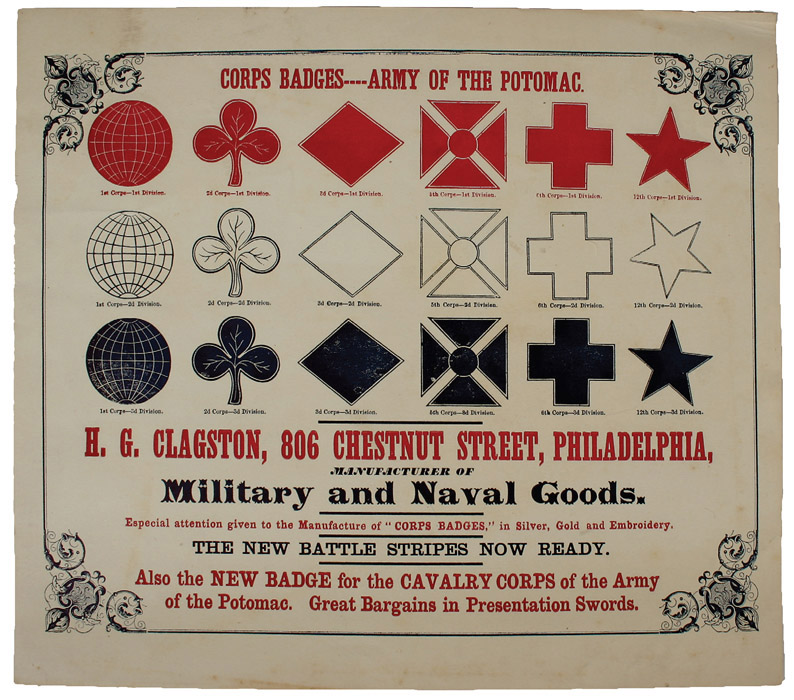

Faded red velvet 2nd Corps Badge on the kepi of staff officer Daniel K. Cross. The embroidered Roman number one represents the 1st Division and below is an Old English “US.” Undoubtedly custom-made for Cross. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

Kepi worn by Captain Daniel K. Cross while serving on the staff of General John C. Caldwell. In addition to the small, embroidered staff wreath on the front, it features a die-cut red cloverleaf badge of the 1st Division of the 2nd Army Corps, over which has been applied a fashionable, embroidered red (faded) velvet badge enclosing the letters “1 US.” DON TROIANI COLLECTION

Private Frederick L. Waterhouse of Company E, 19th Maine Volunteers may have had a lucky escape if the tear in the top of his forage cap was caused by a bullet. Note the early-style 2nd Corps badge cut from sheet tin. MAINE STATE MUSEUM, AUGUSTA, PAUL LOANE PHOTO

Federal forage cap worn at the battle of Gettysburg by Private Philip A. Cooper of Company C of the 140th Pennsylvania Infantry, an embattled regiment that suffered nearly 250 casualties during the second day’s fighting. Of particular note is the original, first pattern, die-cut, cloth trefoil badge of the 2nd Army Corps sewn atop the cap, its red color denoting the 1st Division. JAMES C. FRASCA COLLECTIONS

This large, sheet silver 2nd Corps badge was worn by a popular man, the mail agent. The three enameled colors in the trefoils denote each of the three divisions with the corps. PRIVATE COLLECTION

The first version of the 3rd Army Corps badge was a square turned on the points. Not long after, it evolved into the more familiar oblong shape. Pinned to this officer’s kepi of the 2nd New Hampshire is a die-cut 2nd Division white badge as it would have appeared at the time of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. PRIVATE COLLECTION

A commercial, gilt brass, 3rd Army Corps badge bearing the likeness of General Phillip Kearny, the originator of the Kearny patch. PRIVATE COLLECTION

An officer’s badge with bullion edging of the 3rd Division of the 3rd Army Corps. This reflects the later version, which has become less square in shape. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

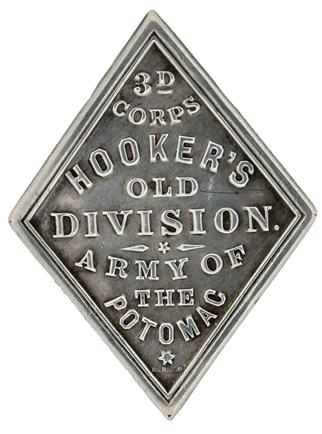

Edward Purcell of the 8th New Jersey Volunteers had this silver 3rd Army Corps badge custom-made for himself. Like many of the earlier badges of the 2nd Division, it proudly proclaims “Hooker’s Old Division” in honor of their old commander, Joseph Hooker. PRIVATE COLLECTION

This silver commercial badge came with all the pertinent information ready-made. The name of a soldier in the 2nd New Hampshire regiment is engraved on the back. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

This 4th Army Corps silver identification badge with cutout “3” for the 3rd Brigade belonged to “W. R. Townsend, Capt. 42nd Ill. Vol.,” from Dowagiac, Michigan. Townsend was captured at Stone River, Tennessee, in December 1862 and later paroled at Chattanooga on January 25, 1865. He was mustered out of military service due to poor health at Chattanooga that same month. WILLIAM ERQUITT COLLECTION

A Clagston commercial, ribbed brass 5th Army Corps badge painted blue for the 3rd Division. PRIVATE COLLECTION

This 3rd Division of the 5th Corps badge was made of blue cloth with a twisted brass wire edge and worn on the cap of George Massey, a drummer in Company K of the 31st Pennsylvania Volunteers. C. PAUL LOANE COLLECTION

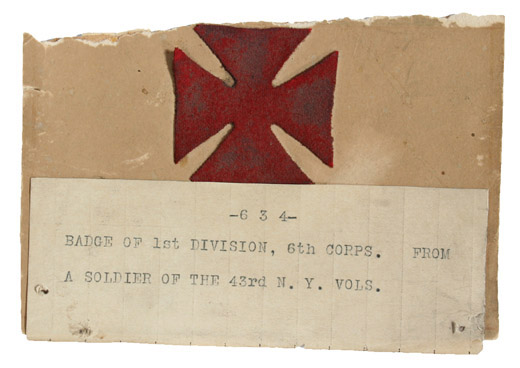

A die-cut 1st Division of the 5th Army Corps badge worn by a soldier of the 43rd New York Volunteers. PRIVATE COLLECTION

John Algie joined the 3rd Delaware on December 30, 1861, at Camden, Delaware, as a private and was mustered into Company A. He was transferred to Company I on May 1, 1862. In early 1864 when the regiment was returned to the Army of the Potomac, they were part of the 2nd Division of the 5th Corps, signified by the white Maltese cross on the cap. The 3rd fought at Cold Harbor, Petersburg, Globe Tavern, Boydton Plank Road, Hatcher’s Run, Five Forks, and Appomattox. Algie was wounded on February 6, 1865, at Hatcher’s Run. Chances are the forage cap was issued after Algie’s convalescence and worn home, since it is a late-war style, made by G & S (Griswold & Son), New York. MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM COLLECTION

This McDowell-style cap was worn by a member of Company G of the 51st Pennsylvania Infantry and features a sewn and pinned cloth badge of the 2nd Division, 9th Corps. It bears the seller’s imprint of John Winnick Currier, City Point, Virginia. Although Currier was appointed additional paymaster, United States Volunteers, January 14, 1863, he declined the post in order to sell military clothing and equipage to the army then based around City Point. JAMES C. FRASCA COLLECTIONS

Silver 6th Corps badge with white enameled center denoting the 2nd Division. This was worn by a soldier in the 6th Maryland Infantry. PRIVATE COLLECTION

Badge of the 6th Army Corps engraved to a soldier of the 2nd Vermont Veteran Volunteers. PRIVATE COLLECTION

The 8th Army Corps unofficially adopted an eight-pointed star, probably in the early summer of 1864. PRIVATE COLLECTION

A brass badge of the 2nd Division of the 9th Army Corps with a white enameled center. PRIVATE COLLECTION

A silver 9th Army Corps badge of the 35th Massachusetts consisting of two pieces attached to a blue ribbon. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

A cloth and bullion-embroidered 10th Army Corps badge for an officer of headquarters staff. The fort-shaped badge is divided into three colored sections, each representing one of the corps divisions. MUSEUM OF CONNECTICUT HISTORY, HARTFORD

10th Army Corps Badge, a commercial frame style, which allows an appropriately colored piece of cloth to be inserted. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

The major of the 169th New York Volunteers provided himself with this superb 10th Corps badge with a cutout silver fort and suspended from a solid gold bar engraved with his name and unit. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

A commercial forage cap with a die-cut badge of the 1st Division of the 10th Army Corps. This cap was worn by Major Samuel Linton of the 39th Illinois Volunteers, who was wounded at Winchester in 1864. C. PAUL LOANE COLLECTION

An 11th Army Corps badge made of tricolored cloth that belonged to Captain Daniel K. Cross, who served on the staff of Major General Oliver Otis Howard in late 1863–1864. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

Officer’s 11th Corps badge of the 2nd Division. The 11th Corps badges were worn in a multitude of ways with points up, down, or horizontally. C. PAUL LOANE COLLECTION

Clagston ribbed, stamped brass, 12th/20th Corps badge painted red for the 1st Division. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

A silver 12th/20th Corps badge with a red enameled center named to a New York soldier. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

A beautiful silver 12th/20th Corps badge, which was worn by a color bearer of the 150th New York Volunteers, William R. Smalley. Carrying the colors in battle was one of the most dangerous jobs on the battlefield, but Smalley fortunately survived his full three years of service. C. PAUL LOANE COLLECTION

On April 26, 1864, the 14th Army Corps adopted the emblem of an acorn as its badge. This rustic silver version belonged to a soldier of Company H of the 78th Illinois Regiment. PRIVATE COLLECTION

Although most Army corps did not have a 4th Division, the 15th did and the prescribed color in that case was yellow. A cartridge box with “40 Rounds” on it was the adopted emblem. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

Stamped brass arrow badge of the 17th Army Corps excavated near Savannah, Georgia, with remains of the cap still attached. This badge was adopted March 25, 1865, in the last days of the war. CAL PACKARD, MUSEUM QUALITY AMERICANA

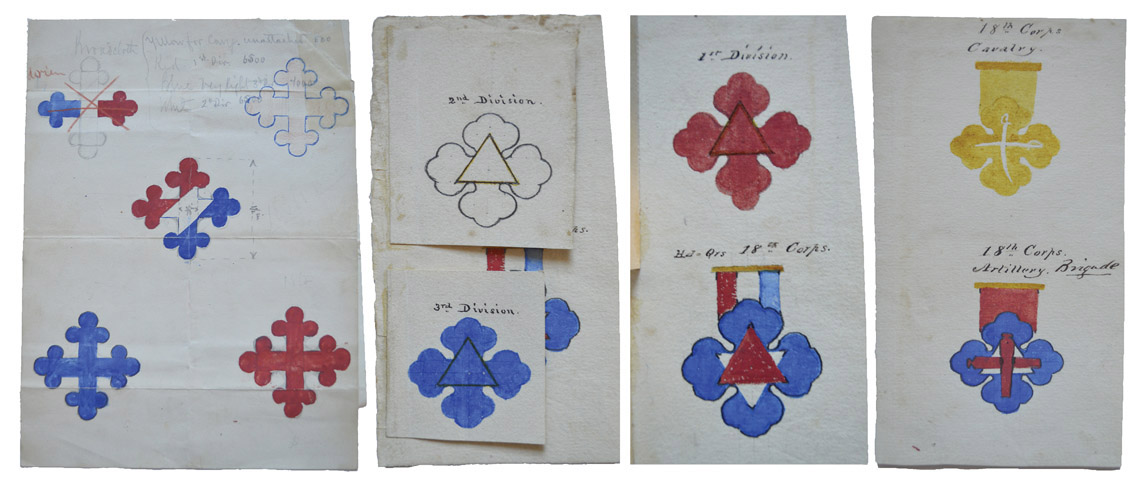

Most Federal Army Corps adopted their own unique badge. This illustration was presented as the badge of the 18th Corps.12 CHRISTOPHER HEIZER PHOTO

Privately purchased, enameled sheet brass, 18th Army Corps badge painted red to signify the 1st Division. This badge was authorized by order on June 7, 1864, and officers were required to wear it on their left breast on a ribbon of the division color, while enlisted men wore theirs in the appropriate color without a ribbon. The issue badges were die-cut cloth, while the commercial were metal. There are a large number of privately purchased variations and types, but this plain example is one of the more common. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

Forage cap worn by Corporal George Schmultz of the 188th Pennsylvania Volunteers. The 1st Division, 18th Corps badge is the commercial frame–style with cloth insert, and the cap is completed with brass numbers and letters with all the other needed information. JAN GORDON COLLECTION

This Clagston stamped metal, four-pointed star badge painted red was the unofficial first badge of the 19th Army Corps, adopted on February 18, 1863. It was supplanted by the fan-leaved cross. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

Issue forage cap with a die-cut, 2nd Division, 19th Army Corps badge worn by Sergeant John E. Bickford of the 38th Massachusetts Volunteers. This fan-leaved cross was the official badge for this corps, adopted on November 17, 1864. MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM COLLECTION

A sheet silver badge of the 22nd Army Corps used by a trooper of the 13th New York Cavalry. PRIVATE COLLECTION

Enlisted man’s forage cap with a die-cut, red cloth badge of the 1st Division of the 24th Army Corps, adopted on March 1, 1865. This was worn by a private of the 24th Massachusetts Regiment. PRIVATE COLLECTION

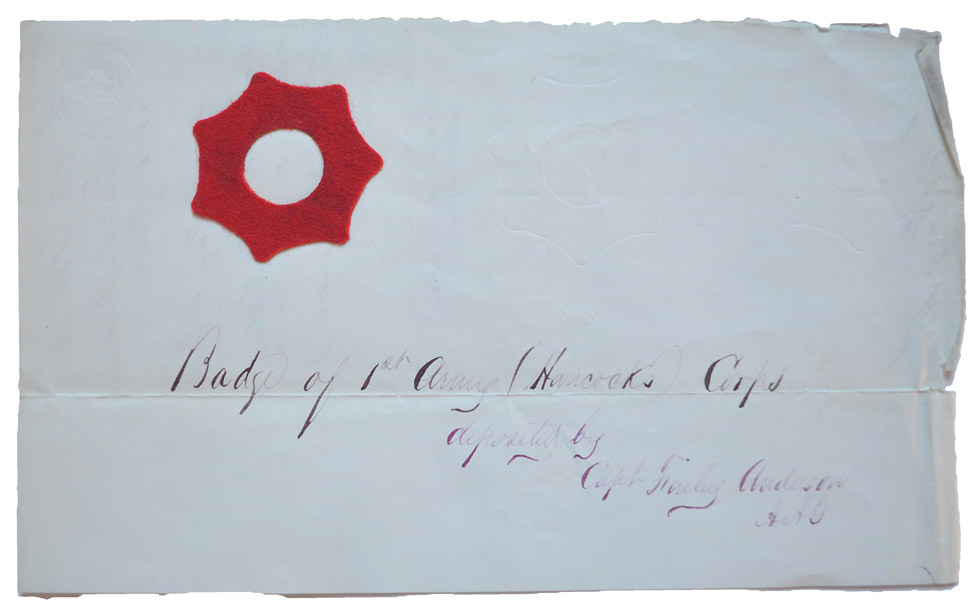

This badge was adopted May 10, 1865 for Hancock’s Veteran Corps. The example was made of red cloth with the center open which would allow the placement of a brass regimental numeral. Unlike other corps, Hancock’s Corps had only regiments which were to serve separately and were not divided into divisions.13