Top texture: © Laguna Design / Science Source;

CHAPTER 14: Repair Systems

Chapter Opener: Laguna Design/Science Source.

14.1 Introduction

Any event that introduces a deviation from the usual double-helical structure of DNA is a threat to the genetic constitution of the cell. Injury to DNA is minimized by systems that recognize and correct the damage. The repair systems are as complex as the replication apparatus itself, which indicates their importance for the survival of the cell. When a repair system reverses a change to DNA, there is no consequence. A mutation may result, though, when it fails to do so. The measured rate of mutation reflects a balance between the number of damaging events occurring in DNA and the number that have been corrected (or miscorrected).

Repair systems recognize a range of distortions in DNA as signals for action. The response to damage includes activation and recruitment of repair enzymes; modification of chromatin structure; activation of cell cycle checkpoints; and, in the event of insufficient repair in multicellular organisms, apoptosis. The importance of DNA repair in eukaryotes is indicated by the identification of more than 130 repair genes in the human genome. As summarized in FIGURE 14.1, we can divide the repair systems into several general types:

Some enzymes directly reverse specific sorts of damage to DNA.

Pathways exist for base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, and mismatch repair, all of which function by removing damaged/mispaired regions and synthesizing new DNA using the intact strand as a template.

Some systems function by using recombination to retrieve an undamaged copy that is then used to replace a damaged duplex sequence.

The nonhomologous end-joining pathway rejoins broken double-strand ends.

Translesion or error-prone DNA polymerases can bypass certain damage or synthesize stretches of replacement DNA that may contain additional errors.

FIGURE 14.1 Repair systems can be classified into pathways that use different mechanisms to reverse or bypass damage to DNA.

Direct repair is rare and involves the reversal or simple removal of the damage. One good example is photoreactivation of pyrimidine dimers, in which inappropriate covalent bonds between adjacent bases are reversed by a light-dependent enzyme.

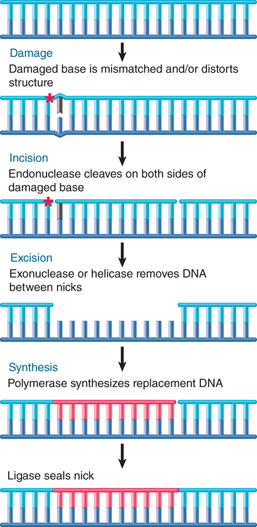

Several pathways of excision repair entail removal of incorrect or damaged sequences followed by repair synthesis. Excision repair pathways are initiated by recognition enzymes that see an actual damaged base or a change in the spatial path of DNA. FIGURE 14.2 summarizes the main events in a generic excision repair pathway. Some excision repair pathways recognize general damage to DNA; others act upon specific types of base damage. A single cell type usually has multiple excision repair systems.

FIGURE 14.2 Excision repair directly replaces damaged DNA and then resynthesizes a replacement stretch for the damaged strand.

Mismatches between the strands of DNA are one of the major targets for excision repair systems. Mismatch repair (MMR) is accomplished by scrutinizing DNA for apposed bases that do not pair properly. This system also recognizes insertion/deletion loops in which sequences present in one strand that are absent in the complementary strand are looped out. Mismatches and insertion/deletion loops that arise during replication are corrected by distinguishing between the “new” and “old” strands and preferentially correcting the sequence of the newly synthesized strand. Other systems deal with mismatches generated by base conversions, such as the result of deamination.

The two major excision repair pathways, in addition to mismatch repair, are as follows:

Base excision repair (BER) systems directly remove the damaged base and replace it in DNA. A good example is uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG; also known as uracil N-glycosylase, UNG), which removes uracils that are mispaired with guanines (see the section in this chapter titled Base Excision Repair Systems Require Glycosylases).

Nucleotide excision repair (NER) systems excise a sequence that includes the damaged base(s); a new stretch of DNA is then synthesized to replace the excised material.

In contrast to excision repair mechanisms, recombination-repair systems handle situations in which damage remains in a daughter molecule and replication has been forced to bypass the site, which typically creates a gap in the daughter strand. A retrieval system uses recombination to obtain another copy of the sequence from an undamaged source; the copy is then used to repair the gap.

A major feature in recombination and repair is the need to handle double-strand breaks (DSBs), which can arise from a variety of mechanisms. DSBs are intentionally created to initiate crossovers during homologous recombination in meiosis. They can also be created by problems in replication, when they may trigger the use of recombination-repair systems. DSBs can also be created by environmental damage (e.g., by radiation damage), intrinsic damage (reactive oxygen species resulting from cellular metabolism), or can be the result from the shortening of telomeres to expose nontelomeric chromosome ends. In all of these events, DSBs can cause mutations, including loss of large chromosomal regions. DSBs can be repaired via recombination-repair using homologous sequences or by joining together nonhomologous DNA ends.

Mutations that affect the ability of Escherichia coli cells to engage in DNA repair fall into groups that correspond to several repair pathways (not necessarily all independent). The major known pathways are the uvr excision repair system, the methyl-directed mut mismatch repair system, and the recB and recF recombination and recombination-repair pathways. The enzyme activities associated with these systems are endonucleases and exonucleases (important in removing damaged DNA); resolvases (endonucleases that act specifically on recombinant junctions); helicases to unwind DNA; and DNA polymerases to synthesize new DNA. Some of these enzyme activities are unique to particular repair pathways, whereas others participate in multiple pathways.

The replication apparatus devotes a lot of attention to quality control. DNA polymerases use proofreading to check the daughter strand sequence and to remove errors. Some of the repair systems are less accurate when they synthesize DNA to replace damaged material. For this reason, these systems have been known historically as error-prone systems.

14.2 Repair Systems Correct Damage to DNA

The types of damage that trigger repair systems can be divided into three general classes: single-base changes, structural distortions/bulky lesions, and strand breaks.

Single-base changes affect the sequence of DNA but do not grossly distort its overall structure. They do not affect transcription or replication when the strands of the DNA duplex are separated. Thus, these changes exert their damaging effects on future generations through the consequences of the change in DNA sequence. The reason for this type of effect is the conversion of one base into another that is not properly paired with the partner base. Single-base changes may happen as the result of mutation of a base in situ or by replication errors. FIGURE 14.3 shows that deamination of cytosine to uracil (spontaneously or by chemical mutagen) creates a mismatched U-G pair. FIGURE 14.4 shows that a replication error might insert adenine instead of cytosine to create an A-G pair. Similar consequences could result from covalent addition of a small group to a base that modifies its ability to base pair. These changes may result in very minor structural distortion (as in the case of a U-G pair) or quite significant change (as in the case of an A-G pair), but the common feature is that the mismatch persists only until the next replication. Thus, only limited time is available to repair the damage before it is made permanent by replication. This repair is mediated by a replication-linked mismatch repair system.

Structural distortions provide a physical impediment to replication or transcription. Introduction of covalent links between bases on one strand of DNA or between bases on opposite strands inhibits replication and transcription. FIGURE 14.5 shows the example of ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, which introduces covalent bonds between two adjacent pyrimidine bases (thymine in this example) and results in an intrastrand pyrimidine dimer, which can take the form of a cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD, as shown in Figure 14.5) or a 6,4 photoproduct (6,4PP). Of all the pyrimidine dimers, thymine–thymine dimers are the most common, and cytosine–cytosine dimers are the least common. In addition, while 6,4PPs are only about one-third as common as CPDs, they may be more mutagenic. These lesions can be repaired by photoreactivation in species that have this repair mechanism. This system is widespread in nature, occurring in all but placental mammals, and appears to be especially important in plants. In E. coli it depends on the product of a single gene (phr) that encodes an enzyme called photolyase. (Placental mammals repair these lesions via excision repair, as described below.)

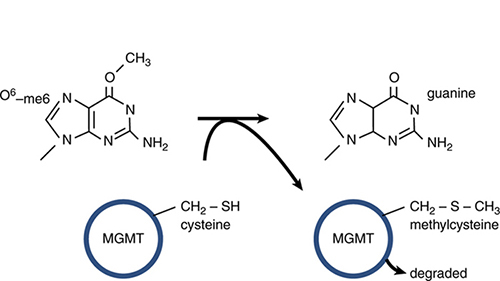

FIGURE 14.6 shows that similar transcription- or replication-blocking consequences can result from the addition of a bulky adduct to a base that distorts the structure of the double helix. In this example, aberrant methylation of guanine results in a lesion that prevents normal base pairing. O 6-methylguanine (O6-meG) is a common mutagenic lesion that can be repaired in several ways. O6-meG is actually a substrate for one of the direct repair pathways: The protein O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) directly transfers the methyl group from O6-meG to a cysteine in MGMT, restoring guanine, as shown in FIGURE 14.7. This is a suicide reaction, in that the methylated MGMT cannot regenerate a free cysteine; instead it is degraded after the repair process.

The loss or removal of a base to create an abasic site, as shown in FIGURE 14.8, prevents a strand from serving as a proper template for synthesis of RNA or DNA. Abasic sites are repaired by excision repair via removal of the phosphodiester backbone where the base is missing.

DNA strand breaks can occur in one strand or both. A single-strand break, or nick, can be directly ligated. DSBs are a major class of damage that, if unrepaired, can result in extensive loss of DNA.

The common feature in all these changes is that the damaged adduct (or break) remains in the DNA and continues to cause structural problems and/or induce mutations until it is removed.

FIGURE 14.3 Deamination of cytosine creates a U-G base pair. Uracil is preferentially removed from the mismatched pair.

FIGURE 14.4 A replication error creates a mismatched pair that may be corrected by replacing one base; if uncorrected, a mutation is fixed in one daughter duplex.

FIGURE 14.5 Ultraviolet irradiation causes dimer formation between adjacent thymines. The dimer blocks replication and transcription.

FIGURE 14.6 Methylation of a base distorts the double helix and causes mispairing at replication. Star indicates the methyl group.

FIGURE 14.7 MGMT can directly transfer a methyl group from O6-meG to a cysteine residue in the protein. This restores guanine but is an irreversible reaction that results in inactivation and degradation of MGMT.

FIGURE 14.8 Depurination removes a base from DNA, blocking replication and transcription.

When a repair system is eliminated, cells become exceedingly sensitive to agents that cause DNA damage, particularly the type of damage recognized by the missing system. The importance of these systems is also emphasized by the fact that mutation of repair genes is associated with the development of a number of cancers in humans, such as Lynch syndrome (also called hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, or HNPCC), caused by defects in mismatch repair.

14.3 Excision Repair Systems in E. coli

Excision repair systems vary in their specificity, but share the same general features. Each system removes mispaired or damaged bases from DNA and then synthesizes a new stretch of DNA to replace them. A general pathway for excision repair is illustrated in FIGURE 14.9, adding more detail to that shown in Figure 14.2.

FIGURE 14.9 Excision repair removes and replaces a stretch of DNA that includes the damaged base(s).

In the incision step, the damaged structure is recognized by an endonuclease that cleaves the DNA strand on both sides of the damage.

In the excision step, a 5′→3′ exonuclease removes a stretch of the damaged strand. Alternatively, a helicase can displace the damaged strand, which is subsequently degraded.

In the synthesis step, the resulting single-stranded region serves as a template for a DNA polymerase to synthesize a replacement for the excised sequence. Synthesis of the new strand can be associated with removal of the old strand, in one coordinated action. Finally, DNA ligase covalently links the 3′ end of the new DNA strand to the original DNA.

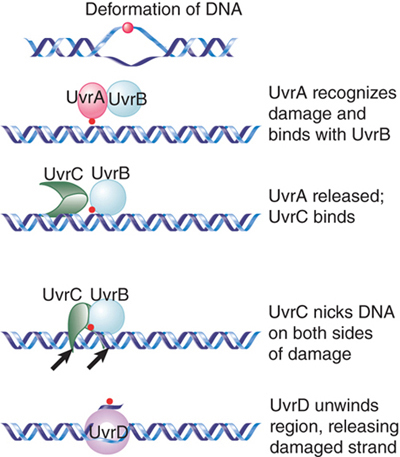

The E. coli uvr system of excision repair includes three genes (uvrA, uvrB, and uvrC), which encode the components of a repair endonuclease. These proteins function in the stages indicated in FIGURE 14.10. First, a UvrAB dimer recognizes pyrimidine dimers and other bulky lesions. Next, UvrA dissociates (this requires adenosine triphosphate [ATP]), and UvrC joins UvrB. The UvrBC complex makes an incision on each side: one that is seven nucleotides from the 5′ side of the damaged site and another that is three to four nucleotides away from the 3′ side. This also requires ATP. UvrD is a helicase that helps to unwind the DNA to allow release of the single strand between the two cuts. The enzyme that excises the damaged strand is DNA polymerase I. The enzyme involved in the repair synthesis also is likely to be DNA polymerase I (although DNA polymerases II and III can substitute for it).

FIGURE 14.10 The Uvr system operates in stages in which UvrAB recognizes damage, UvrBC nicks the DNA, and UvrD unwinds the marked region.

UvrABC repair accounts for virtually all of the excision repair events in E. coli. In almost all cases (99%), the average length of replaced DNA is 12 nucleotides. (For this reason, the process is sometimes described as short-patch repair.) The remaining 1% of cases involves the replacement of stretches of DNA usually around 1,500 nucleotides long, but extending as much as 9,000 nucleotides (sometimes called long-patch repair). We do not know why some events trigger the long-patch rather than the short-patch mode.

The Uvr complex can also be directed to sites of damage by other proteins. Damage to DNA can result in stalled transcription, in which case a protein called Mfd displaces the RNA polymerase and recruits the Uvr complex. FIGURE 14.11 shows a model for the link between transcription and repair. When RNA polymerase encounters DNA damage in the template strand, it stalls because it cannot use the damaged sequences as a template to direct complementary base pairing. This explains the specificity of the effect for the template strand (damage in the nontemplate strand does not impede progress of the RNA polymerase).

FIGURE 14.11 Mfd recognizes a stalled RNA polymerase and directs DNA repair to the damaged template strand.

The Mfd protein has two roles. First, it displaces the ternary complex of RNA polymerase from DNA. Second, it causes the UvrABC enzyme to bind to the damaged DNA, directing excision repair to the damaged strand. After the DNA has been repaired, the next RNA polymerase to traverse the gene is able to produce a normal transcript.

14.4 Eukaryotic Nucleotide Excision Repair Pathways

The general principle of excision repair in eukaryotic cells is similar to that of bacteria. Bulky lesions, such as those created by UV damage, crosslinking agents, and numerous chemical carcinogens, are also recognized and repaired by a nucleotide excision repair system. The critical role of mammalian nucleotide excision repair is seen in certain human hereditary disorders. A well-characterized example is xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), a recessive disease resulting in hypersensitivity to sunlight, and UV light in particular. The deficiency results in skin disorders and cancer predisposition.

The disease is caused by a deficiency in nucleotide excision repair. XP patients cannot excise pyrimidine dimers and other bulky adducts. Mutations occur in one of eight genes called XPA to XPG, all of which encode proteins involved in various stages of nucleotide excision repair. Nucleotide excision repair in eukaryotes proceeds through two major pathways, which are illustrated in FIGURE 14.12.

FIGURE 14.12 Nucleotide excision repair occurs via two major pathways: global genome repair, in which XPC recognizes damage anywhere in the genome, and transcription-coupled repair, in which the transcribed strand of active genes is preferentially repaired and the damage is recognized by an elongating RNA polymerase.

Data from E. C. Friedberg, et al., Nature Rev. Cancer 1 (2001): 22–23.

The major difference between the two pathways is how the damage is initially recognized. In global genome repair (GG-NER), the XPC protein detects the damage and initiates the repair pathway. XPC can recognize damage anywhere in the genome. In mammals, XPC is a component of a lesion-sensing complex that also includes the proteins HR23B and centrin2. XPC also detects distortions that are not repaired by GG-NER (such as small unwound regions of DNA), suggesting other proteins are required to verify the damage bound by XPC. Although XPC recognizes many types of lesions, some types of damage, such as UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs), are not well recognized by XPC. In this case, the DNA damage-binding (DDB) complex assists in recruiting XPC to this type of damage.

In contrast, transcription-coupled repair (TC-NER), as the name suggests, is responsible for repairing lesions that occur in the transcribed strand of active genes. In this case, the damage is recognized by RNA polymerase II itself, which stalls when it encounters a bulky lesion. Interestingly, the repair function may require modification or degradation of RNA polymerase. The large subunit of RNA polymerase is degraded when the enzyme stalls at sites of UV damage.

The two pathways eventually merge and use a common set of proteins to effect the repair itself. The strands of DNA are unwound for about 20 bp around the damaged site. This action is performed by the helicase activity of the transcription factor TFIIH, itself a large complex, which includes the products of two XP genes, XPB and XPD. XPB and XPD are both helicases; the XPB helicase is required for promoter melting during transcription, whereas the XPD helicase performs the unwinding function in NER (though the ATPase activity of XPB is also required during this stage). TFIIH is already present in a stalled transcription complex; as a result, repair of transcribed strands is extremely efficient compared to repair of nontranscribed regions.

In the next step, cleavages are made on either side of the lesion by endonucleases encoded by the XPG and XPF genes. XPG is related to the endonuclease flap endonuclease 1 (FEN1), which cleaves DNA during the base excision repair pathway (see the section in this chapter titled Base Excision Repair Systems Require Glycosylases). XPF is found as part of a two-protein incision complex with ERCC1, which may assist XPF in binding DNA at the site of incision. Typically, about 25 to 30 nucleotides are excised during NER.

Finally, the single-stranded stretch including the damaged bases can then be replaced by new synthesis, and the final remaining nick is ligated by a complex of ligase 3 and XRCC1.

TFIIH, particularly the XPB and XPD subunits, plays numerous and complex roles in NER and transcription. The degradation of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II is deficient in cells from patients with Cockayne syndrome, a repair disorder characterized by neurological impairment and growth deficiency, which may also show photosensitivity similar to that of XP, but without the cancer predisposition. Cockayne syndrome can be caused by mutations in either of two genes (CSA and CSB), both of whose products appear to be part of or bound to TFIIH, and can also be caused by specific mutations in XPB or XPD.

Another disease that can be caused by mutations in XPD is trichothiodystrophy, which has little in common with XP or Cockayne (it is marked by brittle hair and may also include cognitive impairment). All of this marks XPD as a pleiotropic protein, in which different mutations can affect different functions. In fact, XPD is required for the stability of the TFIIH complex during transcription, but its helicase activity is not needed during transcription. Mutations that prevent XPD from stabilizing the complex cause trichothiodystrophy. The helicase activity is required for the repair function. Mutations that affect the helicase activity cause the repair deficiency that results in XP or Cockayne syndrome.

In cases where replication encounters a thymine dimer that has not been removed, replication requires DNA polymerase η activity in order to proceed past the dimer. This polymerase is encoded by XPV. This bypass mechanism allows cell division to proceed even in the presence of unrepaired damage, but this is generally a last resort as cells prefer to put a hold on cell division until all damage is repaired.

14.5 Base Excision Repair Systems Require Glycosylases

Base excision repair is similar to the nucleotide excision repair pathways described in the previous section. The process usually starts in a different way, however, with the removal of an individual damaged base. This serves as the trigger to activate the enzymes that excise and replace a stretch of DNA, including the damaged site.

Enzymes that remove bases from DNA are called glycosylases and lyases. FIGURE 14.13 shows that a glycosylase cleaves the bond between the damaged or mismatched base and the deoxyribose. FIGURE 14.14 shows that some glycosylases are also lyases that can take the reaction a stage further by using an amino (NH2) group to attack the deoxyribose ring. This is usually followed by a reaction that introduces a nick into the polynucleotide chain. FIGURE 14.15 shows that the exact form of the pathway depends on whether the damaged base is removed by a glycosylase or lyase.

FIGURE 14.13 A glycosylase removes a base from DNA by cleaving the bond to the deoxyribose.

FIGURE 14.14 A glycosylase hydrolyzes the bond between base and deoxyribose (using H2O), but a lyase takes the reaction further by opening the sugar ring (using NH2).

FIGURE 14.15 Base removal by glycosylase or lyase action triggers mammalian excision repair pathways.

Glycosylase action is followed by the endonuclease APE1, which cleaves the polynucleotide chain on the 5′ side. This, in turn, attracts a replication complex that includes DNA polymerase δ/ε and ancillary components. The replication complex performs a short synthesis reaction extending for 2 to 10 nucleotides. The displaced material is removed by the flap endonuclease (FEN1). The enzyme ligase 1 seals the chain. This is called the long-patch pathway. (Note that these names refer to mammalian enzymes, but the descriptions are generally applicable for all eukaryotes.)

When the initial removal involves lyase action, the endonuclease APE1 instead recruits DNA polymerase β to replace a single nucleotide. The nick is then sealed by the ligase XRCC1/ligase 3. This is called the short-patch pathway.

Several enzymes that remove or modify individual bases in DNA use a remarkable reaction in which a base is “flipped” out of the double helix. This type of interaction was first demonstrated for methyltransferases—enzymes that add a methyl group to cytosine in DNA. This base-flipping mechanism places the base directly into the active site of the enzyme, where it can be modified and returned to its normal position in the helix or, in the case of DNA damage, immediately excised. Alkylated bases (typically in which a methyl group has been added to a base) are removed by this mechanism. A human enzyme, alkyladenine DNA glycosylase (AAG), recognizes and removes a variety of alkylated substrates, including 3-methyladenine, 7-methylguanine, and hypoxanthine. FIGURE 14.16 shows the structure of AAG bound to a methylated adenine, in which the adenine is flipped out and bound in the glycosylase’s active site.

FIGURE 14.16 Crystal structure of the DNA repair enzyme alkyladenine DNA glycosylase (AAG) bound to a damaged base (3-methyladenine). The base (black) is flipped out of the DNA double helix (blue) and into AAG’s active site (orange and green).

Courtesy of CDC.

By contrast with this mechanism, 1-methyl-adenine is corrected by an enzyme that uses an oxygenating mechanism (encoded in E. coli by the gene alkB, which has homologs in numerous eukaryotes, including three human genes). The methyl group is oxidized to a CH2OH group, and then the release of the HCHO moiety (formaldehyde) restores the structure of adenine. A very interesting discovery is that the bacterial enzyme, and one of the human enzymes, can also repair the same damaged base in RNA. In the case of the human enzyme, the main target may be ribosomal RNA. This is the first known repair event with RNA as a target.

One of the most common reactions in which a base is directly removed from DNA is catalyzed by uracil-DNA glycosylase. Uracil typically only occurs in DNA because of spontaneous deamination of cytosine. It is recognized by the glycosylase and removed. The reaction is similar to that shown in Figure 14.16: The uracil is flipped out of the helix and into the active site in the glycosylase. It appears that most or all glycosylases and lyases (in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes) work in a similar way.

Another enzyme that uses base flipping is the photolyase that reverses the bonds between pyrimidine dimers (see Figure 14.5). The pyrimidine dimer is flipped into a cavity in the enzyme. Close to this cavity is an active site that contains an electron donor, which provides the electrons to break the bonds. Energy for the reaction is provided by light in the visible wavelength. Although most prokaryotic and eukaryotic species possess photolyase, placental mammals (but not marsupials) have lost this activity.

The common feature of these enzymes is the flipping of the target base into the enzyme structure. Recent work has shown that Rad4, the yeast XPC homolog (the protein that recognizes UV damage and other lesions during nucleotide excision repair), uses an interesting variation on this theme. Rad4 flips out the two adenine bases that are complementary to the linked thymines in a pyrimidine dimer, rather than flipping out the damaged pyrimidine dimer itself. In fact, it is believed that the ease with which these unpaired adenines are flipped out is actually the mechanism by which Rad4 detects the damage. Thus, in this case, the target for the subsequent repair is not directly recognized by Rad4 at all, and instead the protein uses flipping as an indirect mechanism to detect the loss of a normal base-paired DNA double helix.

When a base is removed from DNA, the reaction is followed by excision of the phosphodiester backbone by an endonuclease, DNA synthesis by a DNA polymerase to fill the gap, and ligation by a ligase to restore the integrity of the polynucleotide chain, as described for the nucleotide excision repair pathways in the previous section.

14.6 Error-Prone Repair and Translesion Synthesis

The existence of repair systems that engage in DNA synthesis raises the question of whether their quality control is comparable with that of DNA replication. As far as we know, most systems, including uvr-controlled excision repair, do not differ significantly from DNA replication in the frequency of mistakes. Error-prone synthesis of DNA, however, occurs in E. coli under certain circumstances.

The error-prone pathway, also known as translesion synthesis, was first observed when it was found that the repair of damaged λ phage DNA is accompanied by the induction of mutations if the phage is introduced into cells that had previously been irradiated with UV light. This suggests that the UV irradiation of the host has activated functions that generate mutations when repairing λ DNA. The mutagenic response also operates on the bacterial host DNA.

What is the actual error-prone activity? It is a specialized DNA polymerase that inserts random (and thus usually incorrect) bases when it passes any site at which it cannot insert complementary base pairs in the daughter strand. Mutations in the genes umuD and umuC abolish UV-induced mutagenesis. This implies that the UmuC and UmuD proteins cause mutations to occur after UV irradiation. The genes constitute the umuDC operon, whose expression is induced by DNA damage. Their products form a complex, UmuD′2C, which consists of two subunits of a truncated UmuD protein (UmuD′) and one subunit of UmuC. UmuD is cleaved by RecA, which is activated by DNA damage.

The UmuD′2C complex has DNA polymerase activity. It is called DNA polymerase V and is responsible for synthesizing new DNA to replace sequences that have been damaged by UV irradiation. This is the only enzyme in E. coli that can bypass the classic pyrimidine dimers produced by UV irradiation (or other bulky adducts). The polymerase activity is error prone. Mutations in either umuC or umuD inactivate the enzyme, which makes high doses of UV irradiation lethal.

How does an alternative DNA polymerase get access to the DNA? When the replicase (DNA polymerase III) encounters a block, such as a thymidine dimer, it stalls. It is then displaced from the replication fork and replaced by DNA polymerase V. In fact, DNA polymerase V uses some of the same ancillary proteins as DNA polymerase III. The same situation is true for DNA polymerase IV, the product of dinB, which is another enzyme that acts on damaged DNA.

DNA polymerases IV and V are part of a larger family of translesion polymerases, which includes eukaryotic DNA polymerases and whose members are specialized for repairing damaged DNA. In addition to the dinB and umuCD genes that code for DNA polymerases IV and V in E. coli, this family also includes the RAD30 gene coding for DNA polymerase η of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the XPV gene described previously that encodes the human homolog. A difference between the bacterial and eukaryotic enzymes is that the latter are not error prone at thymine dimers: They accurately introduce an A-A pair opposite a T-T dimer. When they replicate through other sites of damage, however, they are more prone to introduce errors.

14.7 Controlling the Direction of Mismatch Repair

Genes whose products are involved in controlling the fidelity of DNA synthesis during either replication or repair may be identified by mutations that have a mutator phenotype. A mutator mutant has an increased frequency of spontaneous mutation. If identified originally by the mutator phenotype, a prokaryotic gene is described as mut; often, though, a mut gene is later found to be equivalent with a known replication or repair activity.

Many mut genes turn out to be components of mismatch repair systems. Failure to remove a damaged or mispaired base before replication allows it to induce a mutation. Functions in this group include the Dam methylase that identifies the target for repair and enzymes that participate directly or indirectly in the removal of particular types of damage (MutH, -S, -L, and -Y).

When a helix-distorting bulky lesion is removed from DNA, the wild-type sequence is restored. In most cases, the distortion is due to the creation of a base that is not naturally found in DNA and that is therefore recognized and removed by the repair system.

A problem arises if the target for repair is a mispaired partnership of (normal) bases created when one was mutated or misinserted during replication. The repair system has no intrinsic means of knowing which is the wild-type base and which is the mutant. All it sees are two improperly paired bases, either of which can provide the target for excision repair.

If the mutated base is excised, the wild-type sequence is restored. If it happens to be the original (wild-type) base that is excised, though, the new (mutant) sequence becomes fixed. Often, however, the direction of excision repair is not random, but instead is biased in a way that is likely to lead to restoration of the wild-type sequence.

Some precautions are taken to direct repair in the right direction. For example, for cases such as the spontaneous deamination of 5-methylcytosine to thymine, a special system restores the proper sequence. This deamination event generates a G-T pair, and the system that acts on such pairs has a bias to correct them to G-C pairs (rather than to A-T pairs). The system that undertakes this reaction includes the MutL and MutS products that remove thymine from both G-T and C-T mismatches.

The MutT, -M, -Y system handles the consequences of oxidative damage. A major type of chemical damage is caused by oxidation of guanine to form 8-oxo-G, which can occur in GTP or when guanine is present in DNA. FIGURE 14.17 shows that the system operates at three levels. MutT hydrolyzes the damaged precursor 8-oxo-dGTP, which prevents it from being incorporated into DNA. When guanine is oxidized in DNA its partner is cytosine, and MutM preferentially removes the 8-oxo-G from 8-oxo-G-C pairs. However, oxidized guanine mispairs with adenine, and so if 8-oxo-G persists in DNA and is replicated, it generates an 8-oxo-G-A pair. MutY removes adenine from these pairs. MutM and MutY are glycosylases that directly remove a base from DNA. This creates an apurinic site that is recognized by an endonuclease whose action triggers the involvement of the excision repair system.

FIGURE 14.17 Preferential removal of bases in pairs that have oxidized guanine is designed to minimize mutations.

When mismatch errors occur during replication in E. coli, it is possible to distinguish the original strand of DNA. Immediately after replication of methylated DNA, only the original parental strand carries methyl groups. In the period during which the newly synthesized strand awaits the introduction of methyl groups, the two strands can be distinguished. This provides the basis for a system to correct replication errors. The dam gene encodes a methyltransferase whose target is the adenine in the sequence CTAG. The hemimethylated state is used to distinguish replicated origins from nonreplicated origins. The same target sites are used by a replication-related mismatch repair system.

FIGURE 14.18 shows that DNA containing mismatched base pairs is repaired by preferentially excising the strand that lacks the methylation. The excision is quite extensive; mismatches can be repaired preferentially for as much as 1 kb around a GATC site. The result is that the newly synthesized strand is corrected to the sequence of the parental strand.

FIGURE 14.18 GATC sequences are targets for Dam methylase after replication. During the period before this methylation occurs, the nonmethylated strand is the target for repair of mismatched bases.

E. coli dam− mutants show an increased rate of spontaneous mutation. This repair system therefore helps reduce the number of mutations caused by errors in replication. It consists of several proteins coded by mut genes. MutS binds to the mismatch and is joined by MutL. MutS can use two DNA-binding sites, as illustrated in FIGURE 14.19. The first specifically recognizes mismatches. The second is not specific for sequence or structure and is used to translocate along DNA until a GATC sequence is encountered. Hydrolysis of ATP is used to drive the translocation. MutS is bound to both the mismatch site and DNA as it translocates, and as a result it creates a loop in the DNA.

FIGURE 14.19 MutS recognizes a mismatch and translocates to a GATC site. MutH cleaves the unmethylated strand at the GATC. Endonucleases degrade the strand from the GATC to the mismatch site.

Recognition of the GATC sequence causes the MutH endonuclease to bind to MutS/L. The endonuclease then cleaves the unmethylated strand. This strand is then excised from the GATC site to the mismatch site. The excision can occur in either the 5′ → 3′ direction (using RecJ or exonuclease VII) or in the 3′ → 5′ direction (using exonuclease I) and is assisted by the helicase UvrD. A new DNA strand is then synthesized by DNA polymerase III.

Eukaryotic cells have systems homologous to the E. coli mut system. Msh2 (“MutS homolog 2”) provides a scaffold for the apparatus that recognizes mismatches. Msh3 and Msh6 provide specificity factors. In addition to repairing single-base mismatches, they are responsible for repairing mismatches that arise as the result of replication slippage. The hMutSβ complex, a Msh2–Msh3 dimer, binds mismatched insertion/deletion loops, whereas the Msh2–Msh6 (hMutSα) complex binds to single-base mismatches. Other proteins, including the MutL homolog hMutLα (a dimer of Mlh1 and Pms2), are required for the repair process itself. Surprisingly, even though multicellular eukaryotes possess DNA methylation that must be restored after replication just as in prokaryotes, eukaryotic mismatch repair systems do not use DNA methylation to select the daughter strand for repair. Eukaryotes recognize the daughter strand during mismatch repair via direct interactions with the replication machinery and preferentially recognizing strands containing nicks as daughter stands. Nicks between Okazaki fragments can serve this purpose on the lagging strand, and hMutLα itself creates DNA ends to use for repair. hMutLα DNA nicking is activated by the replication factor PCNA, which is oriented so as to direct the activity of the repair endonuclease to the nascent daughter strand.

The eukaryotic hMutS/L system is also particularly important for repairing errors caused by replication slippage. In a region such as a microsatellite, where a very short sequence is repeated a number of times, realignment between the newly synthesized daughter strand and its template can lead to a “stuttering” in which the DNA polymerase slips backward and synthesizes extra repeating units or slips forward and skips repeats. The mismatched repeats are extruded as single-stranded insertion-deletion loops (“indels”) from the double helix, which are repaired by homologs of the hMutS/L system, as shown in FIGURE 14.20. Failure to repair insertion-deletion loops leads to repeat contraction or expansion. A number of human diseases, including Huntington’s and Fragile X syndrome, are caused by repeat expansions.

FIGURE 14.20 The MutS/L system initiates repair of mismatches produced by replication slippage.

The importance of the hMutS/L system for mismatch repair is indicated by the high rate at which it is found to be defective in human cancers. Loss of this system leads to an increased mutation rate, and germline mutations in hMutS/L components can lead to Lynch syndrome. These patients have increased risk of colorectal and other cancers (this syndrome has also been called hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, or HNPCC). A characteristic feature of Lynch syndrome is microsatellite instability, in which the lengths (numbers of repeats) of microsatellite sequences change rapidly in the tumor cells due to the loss of the mismatch repair system to correct replication slippage in these sequences. This instability has been used diagnostically to identify Lynch syndrome, but this method has been mostly replaced by immunohistochemistry (IHC) to detect loss of MMR factors in tumor tissue.

14.8 Recombination-Repair Systems in E. coli

Recombination-repair systems use activities that overlap with those involved in genetic recombination. They are also sometimes called postreplication repair because they function after replication. Such systems are effective in dealing with the defects produced in daughter duplexes by replication of a template that contains damaged bases. An example is illustrated in FIGURE 14.21.

FIGURE 14.21 An E. coli retrieval system uses a normal strand of DNA to replace the gap left in a newly synthesized strand opposite a site of unrepaired damage.

Consider a structural distortion, such as a pyrimidine dimer, on one strand of a double helix. When the DNA is replicated, the dimer prevents the damaged site from acting as a template. Replication is forced to skip past it.

DNA polymerase probably proceeds up to or close to the pyrimidine dimer. The polymerase then ceases synthesis of the corresponding daughter strand. Replication restarts some distance farther along. This replication may be performed by translesion polymerases, which can replace the main DNA polymerase at such sites of unrepaired damage (see the section in this chapter titled Error-Prone Repair and Translesion Synthesis). A substantial gap is left in the newly synthesized strand.

The resulting daughter duplexes are different in nature. One has the parental strand containing the damaged adduct, which faces a newly synthesized strand with a lengthy gap. The other duplicate has the undamaged parental strand, which has been copied into a normal complementary strand. The retrieval system takes advantage of the normal daughter.

The gap opposite the damaged site in the first duplex is filled by utilizing the homologous single strand of DNA from the normal duplex. Following this single-strand exchange, the recipient duplex has a parental (damaged) strand facing a wild-type strand. The donor duplex has a normal parental strand facing a gap; the gap can be filled by repair synthesis in the usual way, generating a normal duplex. Thus, the damage is confined to the original distortion (although the same recombination-repair events must be repeated after every replication cycle unless and until the damage is removed by an excision repair system).

The principal recombination-repair pathway in E. coli is identified by the rec genes (see the chapter titled Homologous and Site-Specific Recombination). In E. coli deficient in excision repair, mutation of the recA gene essentially abolishes all the remaining repair and recovery facilities. Attempts to replicate DNA in uvr− recA− cells produce fragments of DNA whose size corresponds with the expected distance between thymine dimers. This result implies that the dimers provide a lethal obstacle to replication in the absence of RecA function. It explains why the double mutant cannot tolerate greater than 1 to 2 dimers in its genome (compared with the ability of a wild-type bacterium to handle as many as 50).

One rec pathway involves the recBC genes and is well characterized; the other involves recF and is not so well defined. They fulfill different functions in vivo. The RecBC pathway is involved in restarting stalled replication forks (see the section in this chapter titled Recombination Is an Important Mechanism to Recover from Replication Errors). The RecF pathway is involved in repairing the gaps in a daughter strand that are left after replicating past a pyrimidine dimer.

The RecBC and RecF pathways both function prior to the action of RecA (although in different ways). They lead to the association of RecA with a single-stranded DNA. The ability of RecA to exchange single strands allows it to perform the retrieval step shown in Figure 14.21. Nuclease and polymerase activities then complete the repair action.

The RecF pathway contains a group of three genes: recF, recO, and recR. The proteins form two types of complexes: RecOR and RecOF. They promote the formation of RecA filaments on single-stranded DNA. One of their functions is to make it possible for the filaments to assemble in spite of the presence of single-strand binding (SSB) protein, which is inhibitory to RecA assembly.

The designations of repair and recombination genes are based on the phenotypes of the mutants, but sometimes a mutation isolated in one set of conditions and named as a uvr gene turns out to have been isolated in another set of conditions as a rec gene. This illustrates the point that the uvr and rec pathways are not independent, because uvr mutants show reduced efficiency in recombination-repair. We must expect to find a network of nuclease, polymerase, and other activities, which constitute repair systems that are partially overlapping (or in which an enzyme usually used to provide some function can be substituted by another from a different pathway).

14.9 Recombination Is an Important Mechanism to Recover from Replication Errors

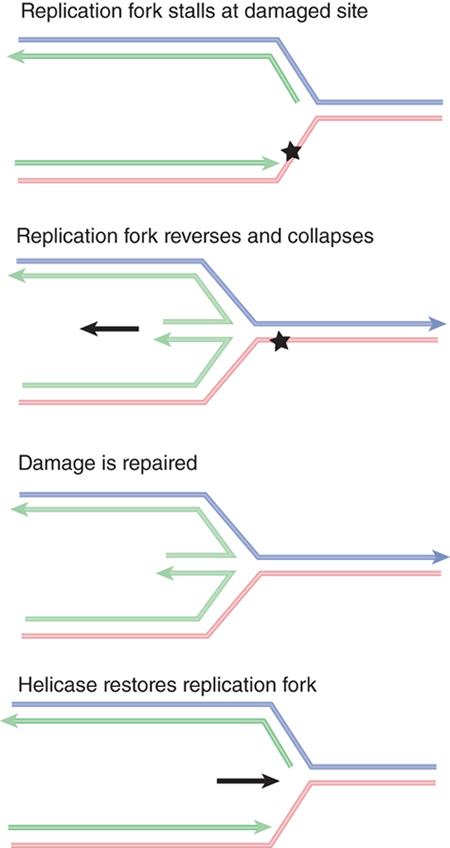

In many cases, rather than skipping a DNA lesion, DNA polymerase instead stops replicating when it encounters DNA damage. FIGURE 14.22 shows one possible outcome when a replication fork stalls. The fork stops moving forward when it encounters the damage. The replication apparatus disassembles, at least partially. This allows branch migration to occur, when the fork effectively moves backward, and the new daughter strands pair to form a duplex structure. After the damage has been repaired, a helicase rolls the fork forward to restore its structure. Then the replication apparatus can reassemble, and replication is restarted (see the DNA Replication chapter).

FIGURE 14.22 A replication fork stalls when it reaches a damaged site in DNA. Reversing the fork allows the two daughter strands to pair. After the damage has been repaired, the fork is restored by forward-branch migration catalyzed by a helicase. Arrowheads indicate 3’ ends.

The pathway for handling a stalled replication fork requires repair enzymes, and restarting stalled replication forks is thought to be a major role of the recombination-repair systems. In E. coli, the RecA and RecBC systems have an important role in this reaction (in fact, this may be their major function in the bacterium). One possible pathway is for RecA to stabilize single-stranded DNA by binding to it at the stalled replication fork and possibly acting as the sensor that detects the stalling event. RecBC is involved in excision repair of the damage. After the damage has been repaired, replication can resume.

Another pathway may use recombination-repair—possibly the strand-exchange reactions of RecA. FIGURE 14.23 shows that the structure of the stalled fork is essentially the same as a Holliday junction created by recombination between two duplex DNAs (see the Homologous and Site-Specific Recombination chapter). This makes it a target for resolvases. A DSB is generated if a resolvase cleaves either pair of complementary strands. In addition, if the damage is in fact a nick, another DSB is created at this site.

FIGURE 14.23 The structure of a stalled replication fork resembles a Holliday junction and can be resolved in the same way by resolvases. The results depend on whether the site of damage contains a nick. Result 1 shows that a double-strand break is generated by cutting a pair of strands at the junction. Result 2 shows that a second double-strand break is generated at the site of damage if it contains a nick. Arrowheads indicate 3’ ends.

Stalled replication forks can be rescued by recombination-repair events. Although the exact sequence of events is not yet known, one possible scenario is outlined in FIGURE 14.24. The principle is that a recombination event occurs on either side of the damaged site, allowing an undamaged single strand to pair with the damaged strand. This allows the replication fork to be reconstructed so that replication can continue, effectively bypassing the damaged site.

FIGURE 14.24 When a replication fork stalls, recombination-repair can place an undamaged strand opposite the damaged site. This allows replication to continue.

14.10 Recombination-Repair of Double-Strand Breaks in Eukaryotes

When a replication fork encounters a lesion in a single stand, it can result in the formation of a DSB. DSBs are one of the most severe types of DNA damage that can occur, particularly in eukaryotes. If a DSB on a linear chromosome is not repaired, the portion of the chromosome lacking a centromere will not be segregated at the next cell division. In addition to their occurrence during replication, DSBs can be generated in a number of other ways, including ionizing radiation, oxygen radicals generated by cellular metabolism, action of endonucleases, attempted excision repair of clustered lesions, or encountering a nick during replication. Four pathways of DSB repair have been identified: homology-directed recombination-repair (HRR; the only error-free pathway), single-strand annealing (SSA), alternative or microhomology-mediated end joining (alt-EJ), and nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ).

The ideal mechanism for repairing DSBs is to use HRR, as this ensures that no critical genetic information is lost due to sequence loss at the breakpoint. HRR is used predominantly during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, when a sister chromatid is available to provide the homologous donor sequence.

Several of the genes required for recombination-repair in eukaryotes have already been discussed in the context of homologous recombination (see the Homologous and Site-Specific Recombination chapter). Many eukaryotic repair genes are named RAD genes; they were initially characterized genetically in yeast by virtue of their sensitivity to radiation. Three general groups of repair genes have been identified in the yeast S. cerevisiae: the RAD3 group (involved in excision repair), the RAD6 group (required for postreplication repair), and the RAD52 group (concerned with recombination-like mechanisms). Homologs of these genes are present in multicellular eukaryotes as well. The RAD52 group plays essential roles in homologous recombination and includes a large number of genes, including RAD50, RAD51, RAD54, RAD55, RAD57, and RAD59. These Rad proteins are all required at different stages of repair of a DSB.

After a break is detected and damage signaling occurs, a stage known as “end clipping” occurs in which the nucleases Mre11 and CtIP trim about 20 nucleotides to generate short single-stranded tails with 3′–OH overhangs. This single-stranded DNA serves to activate a DNA damage checkpoint, stopping cell division until the damage can be repaired. If short sequences in these overhangs are able to base pair (microhomologies), then the alt-EJ pathway can take over, trimming and ligating the ends, with some loss of sequence. Alternatively, as occurs during meiotic recombination, the Mre11/Rad50/Xbs1 (MRX) complex (MRN in mammals) shown in FIGURE 14.25, works in concert with exonucleases and helicases to further resect the ends of the DSB to generate long single-stranded tails. Extensive homology in these longer tails can engage the SSA pathway, which results in large deletions. The factors that control which pathway dominates at any repair event are complex and still not well understood.

In the highly accurate HRR pathway, the RecA homolog Rad51 binds to the single-stranded DNA to form a nucleoprotein filament, which is used for strand invasion of a homologous sequence. Rad52 and the Rad55/57 complex are required to form a stable Rad51 filament, and Rad54 and its homolog Rdh54 (Rad54B in mammals) assist in the search for homologous donor DNA and subsequent strand invasion. Rad54 and Rdh54 are members of the SWI2/SNF2 superfamily of chromatin-remodeling enzymes (see the Eukaryotic Transcription Regulation chapter) and may be necessary for reconfiguring chromatin structure at both the damage site and at the donor DNA. Following repair synthesis, the resulting structure (which resembles a Holliday junction) is resolved (see the Homologous and Site-Specific Recombination chapter for an illustration of these events).

FIGURE 14.25 The MRN complex, required for 5’-end resection, also serves as a DNA bridge to prevent broken ends from separating. The “head” region of Rad50, bound to Mre11, binds DNA, while the extensive coiled coil region of Rad50 ends with a “zinc hook” that mediates interaction with another MRN complex. The precise position of Nbs1 within the complex is unknown, but it interacts directly with Mre11.

14.11 Nonhomologous End Joining Also Repairs Double-Strand Breaks

Repair of DSBs by homologous recombination ensures that no genetic information is lost from a broken DNA end. In many cases, though, a sister chromatid or homologous chromosome is not easily available to use as a template for repair. In addition, some DSBs are specifically repaired using error-prone mechanisms as an intermediate in the recombination of immunoglobulin genes (see the chapter titled Somatic Recombination and Hypermutation in the Immune System). In these cases, the mechanism used to repair these breaks is called nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) and consists of ligating the ends together.

The steps involved in NHEJ are summarized in FIGURE 14.26. The same enzyme complex undertakes the process in both NHEJ and immune recombination. The first stage is recognition of the broken ends by a heterodimer consisting of the proteins Ku70 and Ku80. After the DNA ends are bound by the Ku complex, the MRN complex (or MRX complex in yeast) assists in bringing the broken DNA ends together by acting as a bridge between the two molecules. The MRN complex consists of Mre11, Rad50, and Nbs1 (Xrs2 in yeast). Another key component is the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKcs), which is activated by DNA to phosphorylate protein targets. One of these targets is the protein Artemis, which in its activated form has both exonuclease and endonuclease activities and can trim overhanging ends and cleave the hairpins generated by recombination of immunoglobulin genes. The DNA polymerase activity that fills in any remaining single-stranded protrusions is not known. Frequently during the NHEJ process, mutations are generated through nucleotide deletion and insertion that occurs during the processing steps prior to ligation. The actual joining of the double-stranded ends is performed by DNA ligase IV, which functions in conjunction with the protein XRCC4. Mutations in any of these components may render eukaryotic cells more sensitive to radiation. Some of the genes for these proteins are mutated in patients who have diseases due to deficiencies in DNA repair.

FIGURE 14.26 Nonhomologous end joining. The blue dot on one of the two double-strand break ends signifies a nonligatable end (a). The double-strand break ends are bound by the Ku heterodimer (b). The Ku–DNA complexes are juxtaposed (c) to bridge the ends, and the gap is filled in by processing enzymes and Pol lambda or Pol mu. The ends are ligated by the specialized DNA ligase LigIV with its partner XRCC4 (d) to repair the double-strand break (e).

The Ku heterodimer is the sensor that detects DNA damage by binding to the broken ends. Ku can bring broken ends together by binding two DNA molecules. The crystal structure in FIGURE 14.27 shows why it binds only to ends: The bulk of the protein extends for about two turns along one face of DNA (visible in the lower panel), but a narrow bridge between the subunits, located in the center of the structure, completely encircles DNA. This means that the heterodimer needs to slip onto a free end.

FIGURE 14.27 The Ku70–Ku80 heterodimer binds along two turns of the DNA double helix and surrounds the helix at the center of the binding site.

Structures from Protein Data Bank 1JEY. J. R. Walker, R. A. Corpina, and J. Goldberg, Nature 412 (2001): 607–614.

All of the repair pathways we have discussed are conserved in mammals, yeast, and bacteria. Deficiency in DNA repair causes several human diseases. The inability to repair DSBs in DNA is particularly severe and leads to chromosomal instability. The instability is revealed by chromosomal aberrations, which are associated with an increased rate of mutation, which, in turn, leads to an increased susceptibility to cancer in patients with the disease. The basic cause can be mutation in pathways that control DNA repair or in the genes that encode enzymes of the repair complexes. The phenotypes can be very similar, as in the case of ataxia telangiectasia (AT), which is caused by failure of a cell cycle checkpoint pathway, and Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS), which is caused by a mutation of a repair enzyme.

Nijmegen breakage syndrome results from mutations in a gene encoding a protein (variously called Nibrin, p95, or NBS1) that is a component of the Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 (MRN) repair complex. When human cells are irradiated with agents that induce DSBs, many factors accumulate at the sites of damage, including the components of the MRN complex. After irradiation, the kinase ATM (encoded by the AT gene) phosphorylates NBS1; this activates the complex, which localizes to sites of DNA damage. Subsequent steps involve triggering a checkpoint (a mechanism that prevents the cell cycle from proceeding until the damage is repaired) and recruiting other proteins that are required to repair the damage. Patients deficient in either ATM or NBS1 are immunodeficient, sensitive to ionizing radiation, and predisposed to develop cancer, especially lymphoid cancers.

The recessive human disorder Bloom syndrome is caused by mutations in a helicase gene (called BLM) that is homologous to recQ of E. coli. The mutation results in an increased frequency of chromosomal breaks and sister chromatid exchanges. BLM associates with other repair proteins as part of a large complex. One of the proteins with which it interacts is hMLH1, a mismatch-repair protein that is the human homolog of bacterial MutL. The yeast homologs of these two proteins, Sgs1 and Mlh1, also associate, identifying these genes as parts of a well-conserved repair pathway and illustrating that there is crosstalk between different repair pathways.

14.12 DNA Repair in Eukaryotes Occurs in the Context of Chromatin

DNA repair in eukaryotic cells involves an additional layer of complexity: the nucleosomal packaging of the DNA substrate. Chromatin presents an obstacle to DNA repair, as it does to replication and transcription, because nucleosomes must be displaced in order for processes such as strand unwinding, excision, or resection to occur. Chromatin in the vicinity of DNA damage must therefore be modified and remodeled before or during repair, and then the original chromatin state must be restored after repair is completed, as shown in FIGURE 14.28.

FIGURE 14.28 DNA damage in chromatin requires chromatin remodeling and histone modification for efficient repair; after repair the original chromatin structure must be restored.

Access to DNA in chromatin is controlled by a combination of covalent histone modifications, which change the structure of chromatin and create alternative binding sites for chromatin-binding proteins (discussed in the Chromatin chapter), and ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling (discussed in the Eukaryotic Transcription Regulation chapter), in which remodeling complexes use the energy of ATP to slide or displace nucleosomes. Both histone modification and chromatin remodeling have been implicated in all of the eukaryotic repair pathways discussed in this chapter; for example, both the global-genome and transcription-coupled pathways of nucleotide excision repair depend on specific chromatin-remodeling enzymes, and repair of UV-damaged DNA is facilitated by histone acetylation. A summary of the histone modifications implicated in different repair processes is shown in FIGURE 14.29. All four histones are modified in the course of double-strand break repair (discussed further below), and histone acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination at different sites are differentially involved in different repair pathways.

FIGURE 14.29 Histone modifications associated with different repair pathways. Histone phosphorylation (yellow circle), acetylation (red diamond), methylation (blue square), and ubiquitination (purple hexagon) have all been implicated in repair. Double-strand break repair (DSBR) is grouped as a single pathway, but certain modifications can be specific to different DSBR processes.

Figure generously provided by Nealia C. M. House and Catherine H. Freudenreich.

One of the most extensive posttranslational modifications that occurs following DNA damage (DSBs as well as other damage) in all eukaryotes examined except yeast is the poly-(ADP)-ribosylation (PARylation) of many histone and nonhistone targets. This is catalyzed by enzymes in the poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) superfamily of NAD+-dependent ADP-ribosyltransferases. PAR is a large, branched ADP-ribose polymer that is highly negatively charged, and in some cases the mass of PAR added to a protein can exceed the original mass of the unmodified target! One member of this family, PARP-1, auto-PARylates itself in response to DNA damage, which leads to its association with repair factors and their recruitment to sites of damage. The PARylation is turned over rapidly, and it is thought that this turnover is also important in the DNA damage response.

The best understanding of the roles of chromatin modification, however, is in the repair of DNA DSBs. Much of our understanding of the role of chromatin modification in double-strand break repair (DSBR) comes from studies in yeast utilizing a system derived from the yeast mating-type switching apparatus, which was introduced in the Homologous and Site-Specific Recombination chapter. In this experimental system, yeast strains contain a galactose-inducible HO endonuclease, which generates a unique DSB at the active mating-type locus (MAT) when cells are grown in galactose. These breaks are repaired using the recombination-repair factors described in the section in this chapter titled Recombination-Repair of Double-Strand Breaks in Eukaryotes, using homologous sequences present at the silent mating-type loci HML or HMR. In the absence of homologous donor sequences (or, for haploid yeast, a sister chromatid during S/G2), cells utilize the second major pathway of DSB repair, NHEJ, to directly ligate broken chromosome ends.

Using this system (and other methods for inducing DSBs in mammalian systems as well), researchers have identified numerous histone modifications and chromatin-remodeling events that take place during repair. The best characterized of these is the phosphorylation of the histone H2AX variant (see the Chromatin chapter). The major H2A in yeast is actually of the H2AX type, which is distinguished by an SQEL/Y motif at the end of the C-terminal tail. (This variant makes up only 5% to 15% of the total H2A in mammalian cells.) The serine in the SQEL/Y sequence is the substrate for phosphorylation by the Mec1/Tel1 kinases in yeast, homologs of the mammalian ATM/ATR kinases (ATM is the checkpoint kinase affected in AT patients, discussed in the previous section). H2AX phosphorylated at this site (serine 129 in yeast, 139 in mammals) is referred to as γ-H2AX.

γ-H2AX is a universal marker for DSBs in eukaryotes, whether they occur as a result of damage, or during their normal appearance during mating-type switching in yeast, or during meiotic recombination in numerous species. γ-H2AX phosphorylation is one of the earliest events to occur at a DSB, appearing close to the breakpoint within minutes of damage and spreading to include as much as 50 kb of chromatin in yeast and megabases of chromatin in mammals. γ-H2AX is detectable throughout the repair process and is linked to checkpoint recovery after repair. H2AX phosphorylation stabilizes the association of repair factors at the breakpoint and also serves to recruit chromatin-remodeling enzymes and a histone acetyltransferase to facilitate subsequent stages of repair.

In addition to γ-H2AX, numerous other histone modification events occur at DSBs at defined points during the repair process. Some of these are summarized in FIGURE 14.30, which shows an approximate timeline of modification events at an HO-induced break in yeast. They include transient phosphorylation of H4S1 by casein kinase 2, a modification more important for NHEJ than DSBR, and complex, asynchronous waves of acetylation of both histones H3 and H4 that are controlled by at least three different acetyltransferases and three different deacetylases. It has recently been shown that γ-H2AX is further subject to polyubiquitylation following its phosphorylation, and dephosphorylation of a tyrosine in γ-H2AX (Y142 in mammals) is also critical in the damage response. Certain other preexisting modifications, such as methylated H4K20 and H3K79, also appear to play a role, perhaps by being exposed only upon chromatin conformational changes that occur in response to other modification at a damage site. It is not fully understood how each modification promotes different steps in the repair process (and the details may differ between species), but it is important to note that the patterns of modification differ between homologous recombination and end-joining pathways, suggesting that these modifications may recruit factors specific for the different repair mechanisms.

FIGURE 14.30 Summary of known histone modifications at an HO-induced double-strand break. The approximate timing of events is indicated on the left. Repair rates for homologous recombination and nonhomologous end joining differ in this experimental system, so the precise timing of different modification events relative to one another is not always directly comparable between pathways. The relative distances from the breakpoint are indicated in the upper right (not to scale). Shaded triangles and arcs show distributions and relative levels of the indicated modifications.

A number of chromatin-remodeling enzymes also act at DSBs. All chromatin-remodeling enzymes are members of the SWI2/SNF2 superfamily of enzymes, but there are numerous subfamilies within this group (see the chapter titled Eukaryotic Transcription Regulation). At least three different subfamilies are implicated in DSBR: the SWI/SNF and RSC complexes of the SNF2 subfamily, the INO80 and SWR1 complexes of the INO80 group, and Rad54 and Rdh54 of the Rad54 subfamily. As discussed in the section in this chapter titled Recombination-Repair of Double-Strand Breaks in Eukaryotes, the Rad54 and Rdh54 enzymes play roles during the search for homologous donors and strand-invasion stages of repair, but other chromatin remodelers appear important during every stage, including initial damage recognition, strand resection, and the resetting of chromatin as repair is completed. This final stage also requires the activities of the histone chaperones Asf1 and CAF-1 (introduced in the Chromatin chapter), which are needed to restore chromatin structure on the newly repaired region and allow recovery from the DNA damage checkpoint.

14.13 RecA Triggers the SOS System

When cells respond to DNA damage, the actual repair of the lesion is only one part of the overall response. Eukaryotic cells also engage in two other key types of activities when damage is detected: (1) activation of checkpoints to arrest the cell cycle until the damage is repaired (see the chapter titled Replication Is Connected to the Cell Cycle), and (2) induction of a suite of transcriptional changes that facilitate the damage response (such as production of repair enzymes).

Bacteria also engage in a more global response to damage than just the repair event, known as the SOS response. This response depends on the recombination protein RecA, discussed elsewhere in this chapter. RecA’s role in recombination-repair is only one of its activities. This extraordinary protein also has another quite distinct function: It can be activated by many treatments that damage DNA or inhibit replication in E. coli. This causes it to trigger the SOS response, a complex series of phenotypic changes that involves the expression of many genes whose products include repair functions. These dual activities of the RecA protein make it difficult to know whether a deficiency in repair in recA mutant cells is due to loss of the DNA strand–exchange function of RecA or to some other function whose induction depends on the protease activity.

The inducing damage can take the form of ultraviolet irradiation (the most studied case) or can be caused by crosslinking or alkylating agents. Inhibition of replication by any of several means—including deprivation of thymine, addition of drugs, or mutations in several of the dna genes—has the same effect.

The response takes the form of increased capacity to repair damaged DNA, which is achieved by inducing synthesis of the components of both the long-patch excision repair system and the Rec recombination-repair pathways. In addition, cell division is inhibited. Lysogenic prophages may be induced.

The initial event in the response is the activation of RecA by the damaging treatment. We do not know very much about the relationship between the damaging event and the sudden change in RecA activity. A variety of damaging events can induce the SOS response; thus current work focuses on the idea that RecA is activated by some common intermediate in DNA metabolism.

The inducing signal could consist of a small molecule released from DNA, or it might be some structure formed in the DNA itself. In vitro, the activation of RecA requires the presence of single-stranded DNA and ATP. Thus, the activating signal could be the presence of a single-stranded region at a site of damage. Whatever form the signal takes, its interaction with RecA is rapid: The SOS response occurs within a few minutes of the damaging treatment.

Activation of RecA causes proteolytic cleavage of the product of the lexA gene. LexA is a small (22 kD) protein that is relatively stable in untreated cells, where it functions as a repressor at many operons. The cleavage reaction is unusual: LexA has a latent protease activity that is activated by RecA. When RecA is activated, it causes LexA to undertake an autocatalytic cleavage; this inactivates the LexA repressor function and coordinately induces all the operons to which it was bound. The pathway is illustrated in FIGURE 14.31.

FIGURE 14.31 The LexA protein represses many genes, including the repair genes recA and lexA. Activation of RecA leads to proteolytic cleavage of LexA and induces all of these genes.

The target genes for LexA repression include many with repair functions. Some of these SOS genes are active only in treated cells; others are active in untreated cells, but the level of expression is increased by cleavage of LexA. In the case of uvrB, which is a component of the excision repair system, the gene has two promoters: One functions independently of LexA; the other is subject to its control. Thus, after cleavage of LexA, the gene can be expressed from the second promoter as well as from the first.

LexA represses its target genes by binding to a 20-bp stretch of DNA called an SOS box, which includes a consensus sequence with eight absolutely conserved positions. As is common with other operators, the SOS boxes overlap with the respective promoters. At the lexA locus—the subject of autogenous repression—there are two adjacent SOS boxes.

RecA and LexA are mutual targets in the SOS circuit: RecA triggers cleavage of LexA, which represses recA and itself. The SOS response therefore causes amplification of both the RecA protein and the LexA repressor. The results are not so contradictory as might at first appear.

The increase in expression of RecA protein is necessary (presumably) for its direct role in the recombination-repair pathways. On induction, the level of RecA is increased from its basal level of about 1,200 molecules per cell by up to 50 times. The high level in induced cells means there is sufficient RecA to ensure that all the LexA protein is cleaved. This should prevent LexA from reestablishing repression of the target genes.

The main importance of this circuit for the cell, however, lies in the cell’s ability to return rapidly to normalcy. When the inducing signal is removed, the RecA protein loses the ability to destabilize LexA. At this moment, the lexA gene is being expressed at a high level; in the absence of activated RecA, the LexA protein rapidly accumulates in the uncleaved form and turns off the SOS genes. This explains why the SOS response is freely reversible.

RecA also triggers cleavage of other cellular targets, sometimes with more direct consequences. The UmuD protein is cleaved when RecA is activated; the cleavage event activates UmuD and the error-prone repair system. The current model for the reaction is that the UmuD2UmuC complex binds to a RecA filament near a site of damage, RecA activates the complex by cleaving UmuD to generate UmuD′, and the complex then synthesizes a stretch of DNA to replace the damaged material.

Activation of RecA also causes cleavage of some other repressor proteins, including those of several prophages. Among these is the lambda repressor (with which the protease activity was discovered). This explains why lambda is induced by ultraviolet irradiation: The lysogenic repressor is cleaved, releasing the phage to enter the lytic cycle.

This reaction is not a cellular SOS response, but instead represents recognition by the prophage that the cell is in trouble. Survival is then best assured by entering the lytic cycle to generate progeny phages. In this sense, prophage induction is piggybacking onto the cellular system by responding to the same indicator (activation of RecA).

The two activities of RecA are relatively independent. The recA441 mutation allows the SOS response to occur without inducing treatment, probably because RecA remains spontaneously in the activated state. Other mutations abolish the ability to be activated. Neither type of mutation affects the ability of RecA to handle DNA. The reverse type of mutation, inactivating the recombination function but leaving intact the ability to induce the SOS response, would be useful in disentangling the direct and indirect effects of RecA in the repair pathways.

Summary

All cells contain systems that maintain the integrity of their DNA sequences in the face of damage or errors of replication and that distinguish the DNA from sequences of a foreign source.

Repair systems can recognize mispaired, altered, or missing bases in DNA, as well as other structural distortions of the double helix. Excision repair systems cleave DNA near a site of damage, remove one strand, and synthesize a new sequence to replace the excised material. The uvr system provides the main excision repair pathway in E. coli. The mut and dam systems are involved in correcting mismatches generated by incorporation of incorrect bases during replication and function by preferentially removing the base on the strand of DNA that is not methylated at a dam target sequence. Eukaryotic homologs of the E. coli MutS/L system are involved in repairing mismatches that result from replication slippage; mutations in this pathway are common in certain types of cancer.

Repair systems can be connected with transcription in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Eukaryotes have two major nucleotide excision repair pathways: one that repairs damage anywhere in the genome, and another that specializes in the repair to transcribed strands of DNA. Both pathways depend on subunits of the transcription factor TFIIH. Human diseases are caused by mutations in genes coding for nucleotide excision repair activities, including the TFIIH subunits. They have homologs in the conserved RAD genes of yeast.

Recombination-repair systems retrieve information from a DNA duplex and use it to repair a sequence that has been damaged on both strands. The prokaryotic RecBC and RecF pathways both act prior to RecA, whose strand-transfer function is involved in all bacterial recombination. A major use of recombination-repair may be to recover from the situation created when a replication fork stalls. Genes in the RAD52 group are involved in homologous recombination in eukaryotes.

Nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) is a general mechanism for repairing broken ends in eukaryotic DNA when homologous recombination is not possible. The Ku heterodimer brings the broken ends together so they can be ligated. Several human diseases are caused by mutations in enzymes of both the homologous recombination and nonhomologous end-joining pathways.

All repair occurs in the context of chromatin. Histone modifications and chromatin-remodeling enzymes are required to facilitate repair, and histone chaperones are needed to reset chromatin structure after repair is completed.

RecA has the ability to induce the SOS response. RecA is activated by damaged DNA in an unknown manner. It triggers cleavage of the LexA repressor protein, thus releasing repression of many loci and inducing synthesis of the enzymes of both excision repair and recombination-repair pathways. Genes under LexA control possess an operator SOS box. RecA also directly activates some repair activities. Cleavage of repressors of lysogenic phages may induce the phages to enter the lytic cycle.

References

14.2 Repair Systems Correct Damage to DNA

Reviews

Sancar, A., Lindsey-Boltz, L. A., Unsal-Kaçmaz, K., and Linn, S. (2004). Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 39–85.

Wood, R. D., Mitchell, M., Sgouros, J., and Lindahl, T. (2001). Human DNA repair genes. Science 291, 1284–1289.

14.3 Excision Repair Systems in E. coli

Review

Goosen, N., and Moolenaar, G. F. (2008). Repair of UV damage in bacteria. DNA Repair 7, 353–379.

14.4 Eukaryotic Nucleotide Excision Repair Pathways

Reviews

Barnes, D. E., and Lindahl, T. (2004). Repair and genetic consequences of endogenous DNA base damage in mammalian cells. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38, 445–476.

Bergoglio, V., and Magnaldo, T. (2006). Nucleotide excision repair and related human diseases. Genome Dynamics 1, 35–52.

McCullough, A. K., Dodson, M. L., and Lloyd, R. S. (1999). Initiation of base excision repair: glycosylase mechanisms and structures. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 255–285.

Nouspikel, T. (2009). Nucleotide excision repair: variations on versatility. Cell Mol. Life Sci. PMID 66, 994–1009.

Sancar, A., Lindsey-Boltz, L. A., Unsal-Kaçmaz, K., and Linn, S. (2004). Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 39–85.

Research

Klungland, A., and Lindahl, T. (1997). Second pathway for completion of human DNA base excision-repair: reconstitution with purified proteins and requirement for DNase IV (FEN1). EMBO J. 16, 3341–3348.