Top texture: © Laguna Design / Science Source;

Chapter 19: RNA Splicing and Processing

Chapter Opener: © Laguna Design/Getty Images.

19.1 Introduction

RNA is a central player in gene expression. It was first characterized as an intermediate in protein synthesis, but since then many other RNAs that play structural or functional roles at various stages of gene expression have been discovered. The involvement of RNA in many functions involved with gene expression supports the general view that life may have evolved from an “RNA world” in which RNA was originally the active component in maintaining and expressing genetic information. Many of these functions were subsequently assisted or taken over by proteins, with a consequent increase in versatility and probably efficiency.

All RNAs studied thus far are transcribed from their respective genes and (particularly in eukaryotes) require further processing to become mature and functional. Interrupted genes are found in all groups of eukaryotic organisms. They represent a small proportion of the genes of unicellular eukaryotes, but the majority of genes in multicellular eukaryotic genomes. Genes vary widely according to the numbers and lengths of introns, but a typical mammalian gene has seven to eight exons spread out over about 16 kb. The exons are relatively short (about 100 to 200 bp), and the introns are relatively long (almost 1 kb) (see the chapter titled The Interrupted Gene).

The discrepancy between the interrupted organization of the gene and the uninterrupted organization of its mRNA requires processing of the primary transcription product. The primary transcript has the same organization as the gene and is called the pre-mRNA. Removal of the introns from pre-mRNA leaves an RNA molecule with an average length of about 2.2 kb. Removal of introns is a major part of the processing of RNAs in all eukaryotes. The process by which the introns are removed is called RNA splicing. Although interrupted genes are relatively rare in most unicellular/oligocellular eukaryotes (such as the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae), the overall proportion underestimates the importance of introns because most of the genes that are interrupted encode relatively abundant proteins. Splicing is therefore involved in the production of a greater proportion of total mRNA than would be apparent from analysis of the genome, perhaps as much as 50%.

One of the first clues about the nature of the discrepancy in size between nuclear genes and their products in multicellular eukaryotes was provided by the properties of nuclear RNA. Its average size is much larger than mRNA, it is very unstable, and it has a much greater sequence complexity. Taking its name from its broad size distribution, it is called heterogeneous nuclear RNA (hnRNA).

The physical form of hnRNA is a ribonucleoprotein particle, hnRNP, in which the hnRNA is bound by a set of abundant RNA-binding proteins. Some of the proteins may have a structural role in packaging the hnRNA; several are known to affect RNA processing or facilitate RNA export out of the nucleus.

Splicing occurs in the nucleus, together with the other modifications that are made to newly synthesized RNAs. The process of expressing an interrupted gene is reviewed in FIGURE 19.1. The transcript is capped at the 5′ end, has the introns removed, and is polyadenylated at the 3′ end. The RNA is then transported through nuclear pores to the cytoplasm, where it is available to be translated.

FIGURE 19.1 RNA is modified in the nucleus by additions to the 5′ and 3′ ends and by splicing to remove the introns. The splicing event requires breakage of the exon–intron junctions and joining of the ends of the exons. Mature mRNA is transported through nuclear pores to the cytoplasm, where it is translated.

With regard to the various processing reactions that occur in the nucleus, we should like to know at what point splicing occurs vis-à-vis the other modifications of RNA. Does splicing occur at a particular location in the nucleus, and is it connected with other events—for example, transcription and/or nucleocytoplasmic transport? Does the lack of splicing make an important difference in the expression of uninterrupted genes?

With regard to the splicing reaction itself, one of the main questions is how its specificity is controlled. What ensures that the ends of each intron are recognized in pairs so that the correct sequence is removed from the RNA? Are introns excised from a precursor in a particular order? Is the maturation of RNA used to regulate gene expression by discriminating among the available precursors or by changing the pattern of splicing?

Besides RNA splicing to remove introns, many noncoding RNAs also require processing to mature, and they play roles in diverse aspects of gene expression.

19.2 The 5′ End of Eukaryotic mRNA Is Capped

Transcription starts with a nucleoside triphosphate (usually a purine, A or G). The first nucleotide retains its 5′-triphosphate group and makes the usual phosphodiester bond from its 3′ position to the 5′ position of the next nucleotide. The initial sequence of the transcript can be represented as:

5′pppA/GpNpNpNp …

However, when the mature mRNA is treated in vitro with enzymes that should degrade it into individual nucleotides, the 5′ end does not give rise to the expected nucleoside triphosphate. Instead it contains two nucleotides that are connected by a 5′–5′ triphosphate linkage and also bear a methyl group. The terminal base is always a guanine that is added to the original RNA molecule after transcription.

Addition of the 5′ terminal G is catalyzed by a nuclear enzyme, guanylyl-transferase (GT). In mammals, GT has two enzymatic activities, one functioning as the triphosphatase to remove the two phosphates in GTP and the other as the guanylyl-transferase to fuse the guanine to the original 5′-triphosphate terminus of the RNA. In yeast, these two activities are carried out by two separate enzymes. The new G residue added to the end of the RNA is in the reverse orientation from all the other nucleotides:

5′Gppp + 5′pppApNpNp … → Gppp5′–5′ApNpNp … + pp + p

This structure is called a cap. It is a substrate for several methylation events. FIGURE 19.2 shows the full structure of a cap after all possible methyl groups have been added. The most important event is the addition of a single methyl group at the 7 position of the terminal guanine, which is carried out by guanine-7-methyltransferase (MT).

FIGURE 19.2 The cap blocks the 5′ end of mRNA and can be methylated at several positions.

Although the capping process can be accomplished in vitro using purified enzymes, the reaction normally takes place during transcription. Shortly after transcription initiation, Pol II is paused about 30 nucleotides downstream from the initiation site, waiting for the recruitment of the capping enzymes to add the cap to the 5′ end of nascent RNA. Without this protection, nascent RNA may be vulnerable to attack by 5′–3′ exonucleases, and such trimming may induce the Pol II complex to fall off of the DNA template. Thus, the process of capping is important for Pol II to enter the productive mode of elongation to transcribe the rest of the gene. In this regard, the pausing mechanism for 5′ capping represents a checkpoint for transcription reinitiation from the initial pausing site.

In a population of eukaryotic mRNAs, every molecule contains only one methyl group in the terminal guanine, generally referred to as a monomethylated cap. In contrast, some other small noncoding RNAs, such as those involved in RNA splicing in the spliceosome (see the section later in this chapter titled snRNAs Are Required for Splicing), are further methylated to contain three methyl groups in the terminal guanine. This structure is called a trimethylated cap. The enzymes for these additional methyl transfers are present in the cytoplasm. This may ensure that only some specialized RNAs are further modified at their caps.

One of the major functions for the formation of a cap is to protect the mRNA from degradation. In fact, enzymatic decapping represents one of the major mechanisms to regulate mRNA turnover in eukaryotic cells (see the section later in this chapter titled Splicing Is Temporally and Functionally Coupled with Multiple Steps in Gene Expression). In the nucleus, the cap is recognized and bound by the cap binding CBP20/80 heterodimer. This binding event stimulates splicing of the first intron and, via a direct interaction with the mRNA export machinery (TREX complex), facilitates mRNA export out of the nucleus. Once reaching the cytoplasm, a different set of proteins (eIF4F) binds the cap to initiate translation of the mRNA in the cytoplasm.

19.3 Nuclear Splice Sites Are Short Sequences

To focus on the molecular events involved in nuclear intron splicing, we must consider the nature of the splice sites, the two exon–intron boundaries that include the sites of breakage and reunion. By comparing the nucleotide sequence of a mature mRNA with that of the original gene, the junctions between exons and introns can be determined.

No extensive homology or complementarity exists between the two ends of an intron. However, the splice sites do have well-conserved, though rather short, consensus sequences. It is possible to assign a specific end to every intron by relying on the conservation of exon–intron junctions. They can all be aligned to conform to the consensus sequence shown in the upper portion of FIGURE 19.3.

FIGURE 19.3 The ends of nuclear introns are defined by the GU-AG rule (shown here as GT-AG in the DNA sequence of the gene). Minor introns are defined by different consensus sequences at the 5′ splice site, branch site, and 3′ splice site.

The height of each letter indicates the percent occurrence of the specified base at each consensus position. High conservation is found only immediately within the intron at the presumed junctions. This identifies the sequence of a generic intron as:

GU … … AG

Because the intron defined in this way starts with the dinucleotide GU and ends with the dinucleotide AG, the junctions are often described as conforming to the GU-AG rule. (Of course, the coding strand sequence of DNA has GT-AG.)

Note that the two sites have different sequences, and so they define the ends of the intron directionally. They are named proceeding from left to right along the intron as the 5′ splice site (sometimes called the left, or donor, site) and the 3′ splice site (also called the right, or acceptor, site). The consensus sequences are implicated as the sites recognized in splicing by point mutations that prevent splicing in vivo and in vitro.

In addition to the majority of introns that follow the GU-AG rule, a small fraction of introns are exceptions with a different set of consensus sequences at the exon–intron boundaries, as shown in the lower portion of Figure 19.3. These introns were initially described as minor introns that follow the AU-AC role because of the conserved AU-AC dinucleotides at both ends of each intron, as shown in the middle panel of Figure 19.3. However, the major and minor introns are better described as U2-type and U12-type introns, respectively, based on the distinct splicing machineries that process them (see the section later in this chapter titled An Alternative Spliceosome Uses Different snRNPs to Process the Minor Class of Introns). As a result, some introns that appear to follow the GU-AG rule are actually processed as U12-type introns, as indicated in the lower panel of Figure 19.3.

19.4 Splice Sites Are Read in Pairs

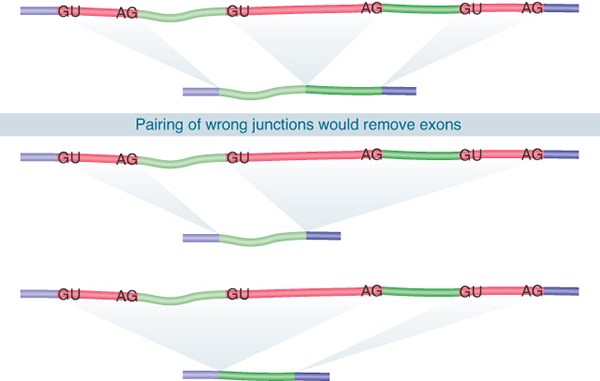

A typical mammalian gene has many introns. The basic problem of pre-mRNA splicing results from the simplicity of the splice sites and is illustrated in FIGURE 19.4. What ensures that the correct pairs of sites are recognized and spliced together in the presence of numerous sequences that match the consensus of bona fide splice sites in the intron? The corresponding GU-AG pairs must be connected across great distances (some introns are more than 100 kb long). We can imagine two types of mechanism that might be responsible for pairing the appropriate 5′ and 3′ splice sites:

It could be an intrinsic property of the RNA to connect the sites at the ends of a particular intron. This would require matching of specific sequences or structures, which has been seen in certain insect genes, but this does not seem to be the case for most eukaryotic genes.

It could be that all 5′ sites may be functionally equivalent and all 3′ sites may be similarly indistinguishable, but splicing could follow rules that ensure a 5′ site is always connected to the 3′ site that comes next in the RNA.

FIGURE 19.4 Splicing junctions are recognized only in the correct pairwise combinations.

Neither the splice sites nor the surrounding regions have any sequence complementarity, which excludes models for complementary base pairing between intron ends. Experiments using hybrid RNA precursors show that any 5′ splice site can in principle be connected to any 3′ splice site. For example, when the first exon of the early SV40 transcription unit is linked to the third exon of mouse β-globin, the hybrid intron can be excised to generate a perfect connection between the SV40 exon and the β-globin exon. Indeed, this interchangeability is the basis for the exon-trapping technique described previously in the chapter titled The Content of the Genome. Such experiments have two general interpretations:

Splice sites are generic. They do not have specificity for individual RNA precursors and individual precursors do not convey specific information (e.g., secondary structure) that is needed for splicing. However, in some cases specific RNA-binding proteins (e.g., hnRNP A1) have been shown to promote splice-site pairing by binding to adjacent prospective splice sites.

The apparatus for splicing is not tissue specific. An RNA can usually be properly spliced by any cell, whether or not it is usually synthesized in that cell. (Exceptions in which there are tissue-specific alternative splicing patterns are presented in the section later in this chapter titled Alternative Splicing Is a Rule, Rather Than an Exception, in Multicellular Eukaryotes.)

If all 5′ splice sites and all 3′ splice sites are similarly recognized by the splicing apparatus, what rules ensure that recognition of splice sites is restricted so that only the 5′ and 3′ sites of the same intron are spliced? Are introns removed in a specific order from a particular RNA?

Splicing is temporally coupled with transcription (e.g., many splicing events are already completed before the RNA polymerase reaches the end of the gene); as a result it is reasonable to assume that transcription provides a rough order of splicing in the 5′ to 3′ direction (something like a first-come, first-served mechanism). Second, a functional splice site is often surrounded by a series of sequence elements that can enhance or suppress the site (see the section later in this chapter titled Splicing Can Be Regulated by Exonic and Intronic Splicing Enhancers and Silencers). Thus, sequences in both exons and introns can also function as regulatory elements for splice-site selection.

We can imagine that, in order to be efficiently recognized by the splicing machinery, a functional splice site has to have the right sequence context, including specific consensus sequences and surrounding splicing-enhancing elements that are dominant over splicing-suppressing elements. These mechanisms together may ensure that splice signals are read in pairs in a relatively linear order.

19.5 Pre-mRNA Splicing Proceeds Through a Lariat

The mechanism of splicing has been characterized in vitro using cell-free systems in which introns can be removed from RNA precursors. Nuclear extracts can splice purified RNA precursors; this shows that the action of splicing does not have to be linked to the process of transcription. Splicing can occur in RNAs that are neither capped nor polyadenylated even though these events normally occur in the cell in a coordinated manner, and the efficiency of splicing may be influenced by transcription and other processing events (see the section later in this chapter titled Splicing Is Temporally and Functionally Coupled with Multiple Steps in Gene Expression).

The stages of splicing in vitro are illustrated in the pathway of FIGURE 19.5. The reaction is discussed in terms of the individual RNA types that can be identified, but remember that in vivo the types containing exons are not released as free molecules but remain held together by the splicing apparatus.

FIGURE 19.5 Splicing occurs in two stages. First the 5′ exon is cleaved off, and then it is joined to the 3′ exon.

FIGURE 19.6 shows that the first step of the splicing reaction is a nucleophilic attack by the 2′–OH on the 5′ splice site. The left exon takes the form of a linear molecule. The right intron–exon molecule forms a branched structure called the lariat, in which the 5′ terminus generated at the end of the intron simultaneously transesterificates to become linked by a 2′–5′ bond to a base within the intron. The target base is an A in a sequence called the branch site.

FIGURE 19.6 Nuclear splicing occurs by two transesterification reactions, in which an –OH group attacks a phosphodiester bond.

In the second step, the free 3′–OH of the exon that was released by the first reaction now attacks the bond at the 3′ splice site. Note that the number of phosphodiester bonds is conserved. There were originally two 5′–3′ bonds at the exon–intron splice sites; one has been replaced by the 5′–3′ bond between the exons and the other has been replaced by the 2′–5′ bond that forms the lariat. The lariat is then “debranched” to give a linear excised intron that is rapidly degraded.

The sequences needed for splicing are the short consensus sequences at the 5′ and 3′ splice sites and at the branch site. Together with the knowledge that most of the sequence of an intron can be deleted without impeding splicing, this indicates that there is no demand for specific conformation in the intron (or exon).

The branch site plays an important role in identifying the 3′ splice site. The branch site in yeast is highly conserved and has the consensus sequence UACUAAC. The branch site in multicellular eukaryotes is not well conserved but has a preference for purines or pyrimidines at each position and retains the target A nucleotide.

The branch site is located 18 to 40 nucleotides upstream of the 3′ splice site. Mutations or deletions of the branch site in yeast prevent splicing. In multicellular eukaryotes, the relaxed constraints in its sequence result in the ability to use related sequences (called cryptic sites) when the authentic branch is deleted or mutated. Proximity to the 3′ splice site appears to be important because the cryptic site is always close to the authentic site. A cryptic site is used only when the branch site has been inactivated. When a cryptic branch sequence is used in this manner, splicing otherwise appears to be normal, and the exons give the same products as the use of the authentic branch site does. The role of the branch site is therefore to identify the nearest 3′ splice site as the target for connection to the 5′ splice site. This can be explained by the fact that an interaction occurs between protein complexes that bind to these two sites.

19.6 snRNAs Are Required for Splicing

The 5′ and 3′ splice sites and the branch sequence are recognized by components of the splicing apparatus that assemble to form a large complex. This complex brings the 5′ and 3′ splice sites together before any reaction occurs, which explains why a deficiency in any one of the sites may prevent the reaction from initiating. The complex assembles sequentially on the pre-mRNA and passes through several “presplicing complexes” before forming the final, active complex, which is called the spliceosome. Splicing occurs only after all the components have assembled.

The splicing apparatus contains both proteins and RNAs (in addition to the pre-mRNA). The RNAs take the form of small molecules that exist as ribonucleoprotein particles. Both the nucleus and cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells contain many discrete small RNA types. They range in size from 100 to 300 bases in multicellular eukaryotes and extend in length to about 1,000 bases in yeast. They vary considerably in abundance, from 105 to 106 molecules per cell to concentrations too low to be detected directly.

Those restricted to the nucleus are called small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs); those found in the cytoplasm are called small cytoplasmic RNAs (scRNAs). In their natural state, they exist as ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNPs and scRNPs). Colloquially, they are sometimes known as snurps and scyrps, respectively. Another class of small RNAs found in the nucleolus, called small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), are involved in processing ribosomal RNA (see the section later in this chapter titled Production of rRNA Requires Cleavage Events and Involves Small RNAs).

The snRNPs involved in splicing, together with many additional proteins, form the spliceosome. Isolated from the in vitro splicing systems, it comprises a 50S to 60S ribonucleoprotein particle. The spliceosome may be formed in stages as the snRNPs join, proceeding through several presplicing complexes. The spliceosome is a large body, greater in mass than the ribosome.

FIGURE 19.7 summarizes the components of the spliceosome. The five snRNAs account for more than a quarter of its mass; together with their 41 associated proteins, they account for almost half of its mass. Some 70 other proteins found in the spliceosome are described as splicing factors. They include proteins required for assembly of the spliceosome, proteins required for it to bind to the RNA substrate, and proteins involved in constructing an RNA-based center for transesterification reactions. In addition to these proteins, another approximately 30 proteins associated with the spliceosome are believed to be acting at other stages of gene expression, which suggests splicing may be connected to other steps in gene expression (see the section later in this chapter titled Splicing Is Temporally and Functionally Coupled with Multiple Steps in Gene Expression).

FIGURE 19.7 The spliceosome is approximately 12 megadaltons (MDa). Five snRNPs account for almost half of the mass. The remaining proteins include known splicing factors, as well as proteins that are involved in other stages of gene expression.

The spliceosome forms on the intact precursor RNA and passes through an intermediate state in which it contains the individual 5′ exon linear molecule and the right-lariat intron–exon. Little spliced product is found in the complex, which suggests that it is usually released immediately following the cleavage of the 3′ site and ligation of the exons.

We may think of the snRNP particles as being involved in building the structure of the spliceosome. Like the ribosome, the spliceosome depends on RNA–RNA interactions as well as protein–RNA and protein–protein interactions. Some of the reactions involving the snRNPs require their RNAs to base pair directly with sequences in the RNA being spliced; other reactions require recognition between snRNPs or between their proteins and other components of the spliceosome.

The importance of snRNA molecules can be tested directly in yeast by inducing mutations in their genes or in in vitro splicing reactions by targeted degradation of individual snRNAs in the nuclear extract. Inactivation of five snRNAs, individually or in combination, prevents splicing. All of the snRNAs involved in splicing can be recognized in conserved forms in all eukaryotes, including plants. The corresponding RNAs in yeast are often rather larger, but conserved regions include features that are similar to the snRNAs of multicellular eukaryotes.

The snRNPs involved in splicing are U1, U2, U5, U4, and U6. They are named according to the snRNAs that are present. Each snRNP contains a single snRNA and several (fewer than 20) proteins. The U4 and U6 snRNPs are usually found together as a di-snRNP (U4/U6) particle. A common structural core for each snRNP consists of a group of eight proteins, all of which are recognized by an autoimmune antiserum called anti-Sm; conserved sequences in the proteins form the target for the antibodies. The other proteins in each snRNP are unique to it. The Sm proteins bind to the conserved sequence A/GAU3–6Gpu, which is present in all snRNAs except U6. The U6 snRNP instead contains a set of Sm-like (Lsm) proteins.

Some of the proteins in the snRNPs may be involved directly in splicing; others may be required in structural roles or just for assembly or interactions between the snRNP particles. About one-third of the proteins involved in splicing are components of the snRNPs. Increasing evidence for a direct role of RNA in the splicing reaction suggests that relatively few of the splicing factors play a direct role in catalysis; most splicing factors may therefore provide structural or assembly roles in the spliceosome.

19.7 Commitment of Pre-mRNA to the Splicing Pathway

Recognition of the consensus splicing signals involves both RNAs and proteins. Certain snRNAs have sequences that are complementary to the mRNA consensus sequences or to one another, and base pairing between snRNA and pre-mRNA, or between snRNAs, plays an important role in splicing.

Binding of U1 snRNP to the 5′ splice site is the first step in splicing. The human U1 snRNP contains the core Sm proteins, three U1-specific proteins (U1-70k, U1A, and U1C), and U1 snRNA. The secondary structure of the U1 snRNA is shown in FIGURE 19.8. It contains several domains. The Sm-binding site is required for interaction with the common snRNP proteins. Domains identified by the individual stem-loop structures provide binding sites for proteins that are unique to U1 snRNP. U1 snRNA interacts with the 5′ splice site by base pairing between its single-stranded 5′ terminus and a stretch of four to six bases of the 5′ splice site.

FIGURE 19.8 U1 snRNA has a base-paired structure that creates several domains. The 5′ end remains single stranded and can base pair with the 5′ splice site.

Mutations in the 5′ splice site and U1 snRNA can be used to test directly whether pairing between them is necessary. The results of such an experiment are illustrated in FIGURE 19.9. The wild-type sequence of the splice site of the 12S adenovirus pre-mRNA pairs at five out of six positions with U1 snRNA. A mutant in the 12S RNA that cannot be spliced has two sequence changes; the GG residues at positions 5 to 6 in the intron are changed to AU. When a mutation is introduced into U1 snRNA that restores pairing at position 5, normal splicing is regained. Other cases, in which corresponding mutations are made in U1 snRNA to see whether they can suppress the mutation in the splice site, suggest this general rule: Complementarity between U1 snRNA and the 5′ splice site is necessary for splicing, but the efficiency of splicing is not determined solely by the number of base pairs that can form.

FIGURE 19.9 Mutations that abolish function of the 5′ splice site can be suppressed by compensating mutations in U1 snRNA that restore base pairing.

The U1 snRNA pairing reaction with the 5′ splicing is stabilized by protein factors. Two such factors play a particular role: The branch point binding protein (BBP, also known as SF1) interacts with the branch point sequence, and U2AF (a heterodimer consisting of U2AF65 and U2AF35 in multicellular eukaryotic cells or Mud2 in the yeast S. cerevisiae) binds to the polypyrimidine tract between the branch point sequence and the invariant AG dinucleotide at the end of each intron. Each of these binding events is not very strong, but together they bind in a cooperative fashion, resulting in the formation of a relatively stable complex called the commitment complex.

The commitment complex is also known as the E complex (E for “early”) in mammalian cells, the formation of which does not require ATP (compared to all late ATP-dependent steps in the assembly of the spliceosome; see the section later in this chapter titled The Spliceosome Assembly Pathway). Unlike in yeast, however, the consensus sequences at the splice sites in mammalian genes are only loosely conserved, and consequently additional protein factors are needed for the formation of the E complex.

The factor or factors that play a central role in this and other spliceosome assembly processes are SR proteins, which constitute a family of splicing factors that contain one or two RNA-recognition motifs at the N-terminus and a signature domain rich with multiple Arg/Ser dipeptide repeats (called the RS domain) at their C-terminus. Their RNA-recognition motifs are responsible for sequence-specific binding to RNA, and the RS domain can bind to both RNA and other splicing factors via protein–protein interactions, thereby providing additional “glue” for various parts of the E complex.

As illustrated in FIGURE 19.10, SR proteins can bind to the 70-kD component of U1 snRNP (the U1 70-kD protein also contains an RS domain, but it is not considered a typical SR protein) to enhance or stabilize its base pairing with the 5′ splice site. SR proteins can also bind to 3′ splice site–bound U2AF (an RS domain is also present in both U2AF65 and U2AF35). These protein–protein interaction networks are thought to be critical for the formation of the E complex. SR proteins copurify with the Pol II complex and are able to kinetically commit RNA to the splicing pathway; thus they likely function as the splicing initiators in multicellular eukaryotic cells.

FIGURE 19.10 The commitment (E) complex forms by the successive addition of U1 snRNP to the 5′ splice site, U2AF to the pyrimidine tract/3′ splice site, and the bridging protein SF1/BBP.

Typical SR proteins are neither encoded in the genome of S. cerevisiae nor needed for splicing by the organism where the splicing signals are nearly invariant, but they are absolutely essential for splicing in all multicellular eukaryotes where the splicing signals are highly divergent. The evolution of SR proteins in multicellular eukaryotes likely contributes to high-efficacy and high-fidelity splicing on loosely conserved splice sites. The recognition of functional splice sites during the formation of the E complex can take two routes, as illustrated in FIGURE 19.11. In S. cerevisiae, where nearly all intron-containing genes are interrupted by a single small intron (between 100 and 300 nucleotides in length), the 5′ and 3′ splice sites are simultaneously recognized by U1 snRNP, BBP, and Mud2, as discussed earlier. This process is referred to as intron definition and is illustrated on the left of Figure 19.11. (Note that the intron definition mechanism applies to small introns in multicellular eukaryotic cells, and thus the figure is drawn with the nomenclature for mammalian splicing factors involved in the process.)

FIGURE 19.11 The two routes for initial recognition of 5′ and 3′ splice sites are intron definition and exon definition.

In comparison, introns are long and highly variable in length in multicellular eukaryotic genomes, and there are many sequences that resemble real splice sites in them. This makes the paired recognition of the 5′ and 3′ splice sites inefficient, if not impossible. The solution to this problem is the process of exon definition, which takes advantage of normally small exons (between 100 and 300 nucleotides in length) in multicellular eukaryotic cells.

As shown on the right side of Figure 19.11, during exon definition the U2AF heterodimer binds to the 3′ splice site and U1 snRNP base pairs with the 5′ splice site downstream from the exon sequence. This process may be aided by SR proteins that bind to specific exon sequences between the 3′ and downstream 5′ splice sites. By an as yet unknown mechanism, the complexes formed across the exon are then switched to the complexes that link the 3′ splice site to the upstream 5′ splice site and the downstream 5′ splice site to the next downstream 3′ splice sites across introns. This establishes the “permissive” configuration that allows later spliceosome assembly steps to occur.

Blockage of this transition is actually a means to regulate the selection of certain exons during regulated splicing (see the section later in this chapter titled Splicing Can Be Regulated by Exonic and Intronic Splicing Enhancers and Silencers). Finally, the exon definition mechanism mediated by SR proteins also provides a mechanism to only allow adjacent 5′ and 3′ splice sites to be paired and linked by splicing.

19.8 The Spliceosome Assembly Pathway

Following formation of the E complex, the other snRNPs and factors involved in splicing associate with the complex in a defined order. FIGURE 19.12 shows the components of the complexes that can be identified as the reaction proceeds.

FIGURE 19.12 The splicing reaction proceeds through discrete stages in which spliceosome formation involves the interaction of components that recognize the consensus sequences.

In the first ATP-dependent step, U2 snRNP joins U1 snRNP on the pre-mRNA by binding to the branch point sequence, which also involves base pairing between the sequence in U2 snRNA and the branch point sequence. This results in the conversion of the E complex to the prespliceosome commonly known as the A complex, and this step requires ATP hydrolysis.

The B1 complex is formed when a trimer containing the U5 and U4/U6 snRNPs binds to the A complex. This complex is regarded as a spliceosome because it contains the components needed for the splicing reaction. It is converted to the B2 complex after U1 is released. The dissociation of U1 is necessary to allow other components to come into juxtaposition with the 5′ splice site, most notably U6 snRNA.

The catalytic reaction is triggered by the release of U4, which also takes place during the transition from the B1 to B2 complex. The role of U4 snRNA may be to sequester U6 snRNA until it is needed. FIGURE 19.13 shows the changes that occur in the base-pairing interactions between snRNAs during splicing. In the U6/U4 snRNP, a continuous length of 26 bases of U6 is paired with two separated regions of U4. When U4 dissociates, the region in U6 that is released becomes free to take up another structure. The first part of it pairs with U2; the second part forms an intramolecular hairpin. The interaction between U4 and U6 is mutually incompatible with the interaction between U2 and U6, so the release of U4 controls the ability of the spliceosome to proceed to the activated state.

FIGURE 19.13 U6/U4 pairing is incompatible with U6/U2 pairing. When U6 joins the spliceosome it is paired with U4. Release of U4 allows a conformational change in U6; one part of the released sequence forms a hairpin and the other part pairs with U2. An adjacent region of U2 is already paired with the branch site, which brings U6 into juxtaposition with the branch. Note that the substrate RNA is reversed from the usual orientation and is shown 3′ to 5′.

For clarity, Figure 19.13 shows the RNA substrate in extended form, but the 5′ splice site is actually close to the U6 sequence immediately on the 5′ side of the stretch bound to U2. This sequence in U6 snRNA pairs with sequences in the intron just downstream of the conserved GU at the 5′ splice site (mutations that enhance such pairing improve the efficiency of splicing).

Thus, several pairing reactions between snRNAs and the substrate RNA occur in the course of splicing. They are summarized in FIGURE 19.14. The snRNPs have sequences that pair with the pre-mRNA substrate and with one another. They also have single-stranded regions in loops that are in close proximity to sequences in the substrate and that play an important role, as judged by the ability of mutations in the loops to block splicing.

FIGURE 19.14 Splicing utilizes a series of base-pairing reactions between snRNAs and splice sites.

The base pairings between U2 and the branch point and between U2 and U6 create a structure that resembles the active center of group II self-splicing introns (see Figure 19.15 in the section titled Pre-mRNA Splicing Likely Shares the Mechanism with Group II Autocatalytic Introns). This suggests the possibility that the catalytic component could comprise an RNA structure generated by the U2–U6 interaction. U6 is paired with the 5′ splice site, and cross-linking experiments show that a loop in U5 snRNA is immediately adjacent to the first base positions in both exons. Although the available evidence points to an RNA-based catalysis mechanism within the spliceosome, contribution(s) by proteins cannot be ruled out. One candidate protein is Prp8, a large scaffold protein that directly contacts both the 5′ and 3′ splice sites within the spliceosome.

Both transesterification reactions take place in the activated spliceosome (the C complex) after a series of RNA arrangements is completed. The formation of the lariat at the branch site is responsible for determining the use of the 3′ splice site, because the 3′ consensus sequence nearest to the 3′ side of the branch becomes the target for the second transesterification.

The important conclusion suggested by these results is that the snRNA components of the splicing apparatus interact both among themselves and with the substrate pre-mRNA by means of base-pairing interactions, and these interactions allow for changes in structure that may bring reacting groups into apposition and may even create catalytic centers.

Although (like ribosomes) the spliceosome is likely a large RNA machine, many protein factors are essential for the machine to run. Extensive mutational analyses undertaken in yeast identified both the RNA and protein components (known as PRP mutants for pre-mRNA processing). Several of the products of these genes have motifs that identify them as a family of ATP-dependent RNA helicases, which are crucial for a series of ATP-dependent RNA rearrangements in the spliceosome.

Prp5 is critical for U2 binding to the branch point during the transition from the E to the A complex; Brr2 facilitates U1 and U4 release during the transition from the B1 to B2 complex; Prp2 is responsible for the activation of the spliceosome during the conversion of the B2 complex to the C complex; and Prp22 helps the release of the mature mRNA from the spliceosome. In addition, a number of RNA helicases play roles in recycling of snRNPs for the next round of spliceosome assembly.

These findings explain why ATP hydrolysis is required from various steps of the splicing reaction, although the actual transesterification reactions do not require ATP. Despite the fact that a sequential series of RNA arrangements takes place in the spliceosome, it is remarkable that the process seems to be reversible after both the first and second transesterification reactions.

19.9 An Alternative Spliceosome Uses Different snRNPs to Process the Minor Class of Introns

GU-AG introns comprise the majority (more than 98%) of splice sites in the human genome. Exceptions to this case are noncanonical splice AU-AC sites and other variations. Initially, this minor class of introns was referred to as AU-AC introns compared to the major class of introns that follow the GU-AG rule during splicing. With the elucidation of the machinery for processing of both major and minor introns, it becomes clear that this nomenclature for the minor class of introns is not entirely accurate.

Guided by years of research on the major spliceosome, the machinery for processing the minor class of introns was quickly elucidated; it consists of U11 and U12 (related to U1 and U2, respectively), a common U5 shared with the major spliceosome, and the U4atac and U6atac snRNAs. The splicing reaction is essentially similar to that of the major class of introns, and the snRNAs play analogous roles: U11 base pairs with the 5′ splice sites; U12 base pairs with the branch point sequence near the 3′ splice site; and U4atac and U6atac provide analogous functions during the spliceosome assembly and activation of the spliceosome.

It turns out that the dependence on the type of spliceosome is also influenced by the sequences in other places in the intron, so that there are some GU-AG introns spliced by the U12-type spliceosome. A strong consensus sequence at the left end defines the U12-dependent type of intron: 5′GAUAUCCUUU … PyAGC3′. In fact, most U12-dependent introns have the GU … AG termini. They have a highly conserved branch point (UCCUUPuAPy), though, which pairs with U12. This difference in branch point sequences is the primary distinction between the major and minor classes of introns. For this reason, the major class of introns is termed U2-dependent introns and the minor class is called U12-dependent introns, instead of AU-AC introns.

The two types of intron coexist in a variety of genomes, and in most cases are found in the same gene. U12-dependent introns tend to be flanked by U2-dependent introns. The phylogeny of these introns suggests that AU-AC U12-dependent introns may once have been more common, but tend to be converted to GU-AG termini, and to U2 dependence, in the course of evolution. The common evolution of the systems is emphasized by the fact that they use analogous sets of base pairing between the snRNAs and with the substrate pre-mRNA. In addition, all essential splicing factors (i.e., SR proteins) studied thus far are required for processing both U2-type and U12-type introns.

One noticeable difference between U2 and U12 types of intron is that U1 and U2 appear to independently recognize the 5′ and 3′ splice sites in the major class of introns during the formation of the E and A complexes, whereas U11 and U12 form a complex in the first place, which together contact the 5′ and 3′ splice sites to initiate the processing of the minor class of introns. This ensures that the splice sites in the minor class of introns are recognized simultaneously by the intron definition mechanism. It also avoids “confusing” the splicing machineries during the transition from exon definition to intron definition for processing the major and minor classes of introns that are present in the same gene.

19.10 Pre-mRNA Splicing Likely Shares the Mechanism with Group II Autocatalytic Introns

Introns in all genes (except nuclear tRNA–encoding genes) can be divided into three general classes. Nuclear pre-mRNA introns are identified only by the presence of the GU … AG dinucleotides at the 5′ and 3′ ends and the branch site/pyrimidine tract near the 3′ end. They do not show any common features of secondary structure. In contrast, group I and group II introns found in organelles and in bacteria (group I introns are also found in the nucleus in unicellular/oligocellular eukaryotes) are classified according to their internal organization. Each can be folded into a typical type of secondary structure.

The group I and group II introns have the remarkable ability to excise themselves from an RNA. This is called autosplicing, or self-splicing. Group I introns are more common than group II introns. There is little relationship between the two classes, but in each case the RNA can perform the splicing reaction in vitro by itself, without requiring enzymatic activities provided by proteins; however, proteins are almost certainly required in vivo to assist with folding (see the Catalytic RNA chapter).

FIGURE 19.15 shows that three classes of introns are excised by two successive transesterifications (shown previously for nuclear introns). In the first reaction, the 5′ exon–intron junction is attacked by a free hydroxyl group (provided by an internal 2′–OH position in nuclear and group II introns or by a free guanine nucleotide in group I introns). In the second reaction, the free 3′–OH at the end of the released exon in turn attacks the 3′ intron–exon junction.

FIGURE 19.15 Three classes of splicing reactions proceed by two transesterifications. First, a free –OH group attacks the exon 1–intron junction. Second, the –OH created at the end of exon 1 attacks the intron–exon 2 junction.

Parallels exist between group II introns and pre-mRNA splicing. Group II mitochondrial introns are excised by the same mechanism as nuclear pre-mRNAs via a lariat that is held together by a 2′–5′ bond. When an isolated group II RNA is incubated in vitro in the absence of additional components, it is able to perform the splicing reaction. This means that the two transesterification reactions shown in Figure 19.15 can be performed by the group II intron RNA sequence itself. The number of phosphodiester bonds is conserved in the reaction, and as a result an external supply of energy is not required; this could have been an important feature in the evolution of splicing.

A group II intron forms a secondary structure that contains several domains formed by base-paired stems and single-stranded loops. Domain 5 is separated by two bases from domain 6, which contains an A residue that donates the 2′–OH group for the first transesterification. This constitutes a catalytic domain in the RNA. FIGURE 19.16 compares this secondary structure with the structure formed by the combination of U6 with U2 and of U2 with the branch site. The similarity suggests that U6 may have a catalytic role in pre-mRNA splicing.

FIGURE 19.16 Nuclear splicing and group II splicing involve the formation of similar secondary structures. The sequences are more specific in nuclear splicing; group II splicing uses positions that may be occupied by either purine (R) or pyrimidine (Y).

The features of group II splicing suggest that splicing evolved from an autocatalytic reaction undertaken by an individual RNA molecule, in which it accomplished a controlled deletion of an internal sequence. It is likely that such a reaction would require the RNA to fold into a specific conformation, or series of conformations, and would occur exclusively in cis-conformation.

The ability of group II introns to remove themselves by an autocatalytic splicing event stands in great contrast to the requirement of nuclear introns for a complex splicing apparatus. The snRNAs of the spliceosome can be regarded as compensating for the lack of sequence information in the intron, and as providing the information required to form particular structures in RNA. The functions of the snRNAs may have evolved from the original autocatalytic system. These snRNAs act in trans upon the substrate pre-mRNA. Perhaps the ability of U1 to pair with the 5′ splice site, or of U2 to pair with the branch sequence, replaced a similar reaction that required the relevant sequence to be carried by the intron. Thus, the snRNAs may undergo reactions with the pre-mRNA substrate—and with one another—that have substituted for the series of conformational changes that occur in RNAs that splice by group II mechanisms. In effect, these changes have relieved the substrate pre-mRNA of the obligation to carry the sequences needed to sponsor the reaction. As the splicing apparatus has become more complex (and as the number of potential substrates has increased), proteins have played a more important role.

19.11 Splicing Is Temporally and Functionally Coupled with Multiple Steps in Gene Expression

Pre-mRNA splicing has long been recognized to take place cotranscriptionally, though the two reactions can take place separately in vitro and have been studied as separate processes in gene expression. Major experimental evidence supporting cotranscriptional splicing came from the observations that many splicing events are completed before the completion of transcription. In general, introns near the 5′ end of the gene are removed during transcription, but introns near the end of the gene can be processed either during or after transcription.

Besides temporal coupling between transcription and splicing, there are probably other reasons for these two key processes to be linked in a functional way. Indeed, the machineries for 5′ capping, intron removal, and even polyadenylation at the 3′ end (see the section later in this chapter titled 3′ mRNA End Processing Is Critical for Termination of Transcription) show physical interactions with the core machinery for transcription. A common mechanism is to use the large C-terminal domain of the largest subunit of Pol II (known as CTD) as a loading pad for various RNA-processing factors, although in most cases it is yet to be defined whether the tethering is direct or mediated by some common protein or even RNA factors (see the Eukaryotic Transcription chapter).

Such physical integration would ensure efficient recognition of emerging splicing signals to pair adjacent functional splice sites during transcription, thus maintaining a rough order of splicing from the 5′ to 3′ direction. The recognition of the emerging splicing signals by the RNA-processing factors and enzymes associated with the elongation Pol II complex would also allow these factors to compete effectively with other nonspecific RNA-binding proteins, such as hnRNP proteins, that are abundantly present in the nucleus for RNA packaging.

If RNA splicing benefits from transcription, why not the other way around? In fact, increasing evidence has suggested so; as illustrated in FIGURE 19.17, the 5′ capping enzymes seem to help overcome initial transcriptional pausing near the promoter; splicing factors appear to play some roles in facilitating transcriptional elongation; and the 3′ end formation of mRNA is clearly instrumental to transcriptional termination (see the section later in this chapter titled 3′ mRNA End Processing Is Critical for Termination of Transcription). Thus, transcription and RNA processing are highly coordinated in multicellular eukaryotic cells.

FIGURE 19.17 Coupling transcription with the 5′ capping reaction. Pol II transcription is initially paused near the transcription start point. Both guanylyl-transferase (GT) and 7-methyltransferase (MT) are recruited to the Pol II complex to catalyze 5′ capping, and the cap is bound by the cap-binding protein complex at the 5′ end of the nascent transcript. These reactions allow the paused Pol II to enter the mode of productive elongation.

RNA processing is functionally linked not only to the upstream transcriptional events but also to downstream steps, such as mRNA export and stability control. It has been known for a long time that intermediately processed RNA that still contains some introns cannot be exported efficiently, which may be due to the retention effect of the spliceosome in the nucleus. Splicing-facilitated mRNA export can be demonstrated by nuclear injection of intronless RNA derived from cDNA or pre-mRNA that will give rise to identical RNA upon splicing. The RNA that has gone through the splicing process is exported more efficiently than the RNA derived from the cDNA, indicating that the splicing process helps mRNA export.

As illustrated in FIGURE 19.18, a specific complex, called the exon junction complex (EJC), is deposited onto the exon–exon junction. This complex appears to directly recruit a number of RNA-binding proteins implicated in mRNA export. Apparently, these mechanisms may act in synergy to promote the export of mRNA coming out of transcription and the cotranscriptional RNA-splicing apparatus. This process may start early in transcription. The cap binding CBP20/80 complex appears to directly bind to the mRNA export machinery (the TREX complex) in a manner that depends on splicing to remove the first intron near the 5′ end to facilitate mRNA export. A key factor in mediating mRNA export is REE (also named Aly, Yra1 in yeast), which is part of the EJC and can directly interact with the mRNA transporter TAP (Mex67 in yeast), as shown in FIGURE 19.19.

FIGURE 19.18 The exon junction complex (EJC) is deposited near the splice junction as a consequence of the splicing reaction.

FIGURE 19.19 An REF protein (shown in green) binds to a splicing factor and remains with the spliced RNA product. REF binds to a transport protein (shown in purple) that binds to the nuclear pore.

The EJC complex has an additional role in escorting mRNA out of the nucleus, which has a profound effect on mRNA stability in the cytoplasm. This is because an EJC that has retained some aberrant mRNAs can recruit other factors that promote decapping enzymes to remove the protective cap at the 5′ end of the mRNA. As illustrated in FIGURE 19.20, the EJC is normally removed by the scanning ribosome during the first round of translation in the cytoplasm. If, however, for some reason a premature stop codon is introduced into a processed mRNA as a result of point mutation or alternative splicing (see the next section, titled Alternative Splicing Is a Rule, Rather Than an Exception, in Multicellular Eukaryotes), the ribosome will fall off before reaching the natural stop codon, which is typically located in the last exon. The inability of the ribosome to strip off the EJC complex deposited after the premature stop codon will allow the recruitment of decapping enzymes to induce rapid degradation of the mRNA. This process is called nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD), which represents an mRNA surveillance mechanism that prevents translation of truncated proteins from the mRNA that carries a premature stop codon (NMD is discussed further in the mRNA Stability and Localization chapter).

FIGURE 19.20 The EJC complex couples splicing with NMD. The EJC can also recruit Upr proteins if it remains on the exported mRNA. After nuclear export, EJC should be tripped off by the scanning ribosome in the first round of translation. If an EJC remains on the mRNA because of a premature stop codon in the front, which releases the ribosome, the EJC will recruit additional proteins, such as Upf, which will then recruit the decapping enzyme (DCP). This will induce decapping at the 5′ end and mRNA degradation from the 5′ to 3′ direction in the cytoplasm.

19.12 Alternative Splicing Is a Rule, Rather Than an Exception, in Multicellular Eukaryotes

When an interrupted gene is transcribed into an RNA that gives rise to a single type of spliced mRNA, the assignment of exons and introns is unambiguous. However, the RNAs of most mammalian genes follow patterns of alternative splicing, which occurs when a single gene gives rise to more than one mRNA sequence. By large-scale cDNA cloning and sequencing, it has become apparent that more than 90% of the genes expressed in mammals are alternatively spliced. Thus, alternative splicing is not just the result of mistakes made by the splicing machinery; it is part of the gene expression program that results in multiple gene products from a single gene locus.

Various modes of alternative splicing have been identified, including intron retention, alternative 5′ splice-site selection, alternative 3′ splice-site selection, exon inclusion or skipping, and mutually exclusive selection of the alternative exons, as summarized in FIGURE 19.21. A single primary transcript may undergo more than one mode of alternative splicing. The mutually exclusive exons are normally regulated in a tissue-specific manner. Adding to this complexity, in some cases the ultimate pattern of expression is also dictated by the use of different transcription start points or the generation of alternative 3′ ends.

FIGURE 19.21 Different modes of alternative splicing.

Alternative splicing can affect gene expression in the cell in at least two ways. One way is to create structural diversity of gene products by including or omitting some coding sequences or by creating alternative reading frames for a portion of the gene. This can often modify the functional property of encoded proteins. For example, the CaMKIIδ gene contains three alternatively spliced exons, as shown in FIGURE 19.22. The gene is expressed in almost all cell types and tissues in mammals. When all three alternative exons are skipped, the mRNA encodes a cytoplasmic kinase that phosphorylates a large number of protein substrates. When exon 14 is included, the kinase is transported to the nucleus because exon 14 contains a nuclear localization signal. This allows the kinase to regulate transcription in the nucleus. When both exons 15 and 16 are included, which is normally detected in neurons, the kinase is targeted to the cell membrane, where it can influence specific ion channel activities.

FIGURE 19.22 Alternative splicing of the CaMKIIδ gene: different alternative exons target the kinase to different cellular compartments.

In other cases, the alternatively spliced products exhibit opposite functions. This applies to essentially all genes involved in the regulation of apoptosis; each gene expresses at least two isoforms, one functioning to promote apoptosis and the other protecting cells against apoptosis. It is thought that the isoform ratios of these apoptosis regulators may dictate whether the cell lives or dies.

Alternative splicing may also affect various properties of the mRNA by including or omitting certain regulatory RNA elements, which may significantly alter the half-life of the mRNA. In many cases, the main purpose of alternative splicing may be to cause a certain percentage of primary transcripts to carry a premature stop codon(s) so that those transcripts can be rapidly degraded. This may represent an alternative strategy to transcriptional regulation to control the abundance of specific mRNAs in the cell. This mechanism is used to achieve homeostatic expression for many splicing regulators in specific cell types or tissues. In such regulation, a specific positive splicing regulator may affect its own alternative splicing, resulting in the inclusion of an exon containing a premature stop codon. This siphons a fraction of its mRNA to degradation, thereby reducing the protein concentration. Thus, when the concentration of such positive splicing regulator fluctuates in the cell, its mRNA concentration will be shifted in the opposite direction.

Although many alternative splicing events have been characterized and the biological roles of the alternatively spliced products determined, the best understood example is still the pathway of sex determination in D. melanogaster, which involves interactions between a series of genes in which alternative splicing events distinguish males and females. The pathway takes the form illustrated in FIGURE 19.23, in which the ratio of X chromosomes to autosomes determines the expression of sex lethal (sxl), and changes in expression are passed sequentially through the other genes to doublesex (dsx), the last in the pathway.

FIGURE 19.23 Sex determination in D. melanogaster involves a pathway in which different splicing events occur in females. Blockages at any stage of the pathway result in male development. Illustrated are tra pre-mRNA splicing controlled by the Sxl protein, which blocks the use of the alternative 3′ splice site, and dsx pre-mRNA splicing regulated by both Tra and Tra2 proteins in conjunction with other SR proteins, which positively influence the inclusion of the alternative exon.

The pathway starts with sex-specific splicing of sxl. Exon 3 of the sxl gene contains a termination codon that prevents synthesis of functional protein. This exon is included in the mRNA produced in males but is skipped in females. As a result, only females produce Sxl protein. The protein has a concentration of basic amino acids that resembles other RNA-binding proteins. The presence of Sxl protein changes the splicing of the transformer (tra) gene. Figure 19.23 shows that this involves splicing a constant 5′ site to alternative 3′ sites (note that this mode applies to both sxl and tra splicing, as illustrated). One splicing pattern occurs in both males and females and results in an RNA that has an early termination codon. The presence of Sxl protein inhibits usage of the upstream 3′ splice site by binding to the polypyrimidine tract at its branch site. When this site is skipped, the next 3′ site is used. This generates a female-specific mRNA that encodes a protein.

Thus, Sxl autoregulates the splicing of its own mRNA to ensure its expression in females, and tra produces a protein only in females; like Sxl, Tra protein is a splicing regulator. tra2 has a similar function in females (but is also expressed in the males). The Tra and Tra2 proteins are SR splicing factors that act directly upon the target transcripts. Tra and Tra2 cooperate (in females) to affect the splicing of dsx. In the dsx gene, females splice the 5′ site of intron 3 to the 3′ site of that intron; as a result, translation terminates at the end of exon 4. Males splice the 5′ site of intron 3 directly to the 3′ site of intron 4, thus omitting exon 4 from the mRNA and allowing translation to continue through exon 6. The result of the alternative splicing is that different Dsx proteins are produced in each sex: The male product blocks female sexual differentiation, whereas the female product represses expression of male-specific genes.

19.13 Splicing Can Be Regulated by Exonic and Intronic Splicing Enhancers and Silencers

Alternative splicing is generally associated with weak splice sites, meaning that the splicing signals located at both ends of introns diverge from the consensus splicing signals. This allows these weak splicing signals to be modulated by various trans-acting factors generally known as alternative splicing regulators. However, contrary to common assumptions, these weak splice sites are generally more conserved across mammalian genomes than are constitutive splice sites. This observation is evidence against the notion that alternative splicing might result from splicing mistakes by the splicing machinery and favors the possibility that many alternative splicing events might be evolutionarily conserved to preserve the regulation of gene expression at the level of RNA processing.

The regulation of alternative splicing is a complex process, involving a large number of RNA-binding trans-acting splicing regulators. As illustrated in FIGURE 19.24, these RNA-binding proteins may recognize RNA elements in exons and introns near the alternative splice site and exert positive and negative influence on the selection of the alternative splice site. Those that bind to exons to enhance the selection are positive splicing regulators and the corresponding cis-acting elements are referred to as exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs). SR proteins are among the best characterized ESE-binding regulators. In contrast, some RNA-binding proteins, such as hnRNP A and B, bind to exonic sequences to suppress splice site selection; the corresponding cis-acting elements are thus known as exonic splicing silencers (ESSs). Similarly, many RNA-binding proteins affect splice-site selection through intronic sequences. The corresponding positive and negative cis-acting elements in introns thus are called intronic splicing enhancers (ISEs) or intronic splicing silencers (ISSs).

FIGURE 19.24 Exonic and intronic sequences can modulate splice-site selection by functioning as splicing enhancers or silencers. In general, SR proteins bind to exonic splicing enhancers and the hnRNP proteins (e.g., the A and B families of RNA-binding proteins [RBPs]) bind to exonic silencers. Other RBPs can function as splicing regulators by binding to intronic splicing enhancers or silencers.

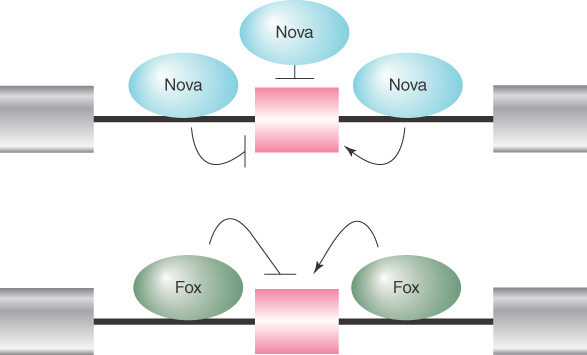

Adding to this complexity are the positional effects of many splicing regulators. The best-known examples are the Nova and Fox families of RNA-binding splicing regulators, which can enhance or suppress splice-site selection, depending on where they bind relative to the alternative exon. For example, as illustrated in FIGURE 19.25, binding of both Nova and Fox to intronic sequences upstream of the alternative exon generally results in the suppression of the exon, whereas their binding to intronic sequences downstream of the alternative splicing exon frequently enhances the selection of the exon. Both Nova and Fox are differentially expressed in different tissues, particularly in the brain. Thus, tissue-specific regulation of alternative splicing can be achieved by tissue-specific expression of trans-acting splicing regulators.

FIGURE 19.25 The Nova and Fox families of RNA-binding proteins can promote or suppress splice site selection in a context-dependent fashion. Binding of Nova to exons and flanking upstream introns inhibits the inclusion of the alternative exon, whereas Nova binding to the downstream flanking intronic sequences promotes the inclusion of the alternative exon. Fox binding to the upstream intronic sequence inhibits the inclusion of the alternative exon, whereas binding of Fox to the downstream intronic sequence promotes the inclusion of the alternative exon.

How a specific alternative splicing event is regulated by various positive and negative splicing regulators is not completely understood. In principle, these splicing regulators function to enhance or suppress the recognition of specific splicing signals by some of the core components of the splicing machinery. The best-understood cases are SR proteins and hnRNA A/B proteins for their positive and negative roles in enhancing or suppressing splice-site recognition, respectively. Binding of SR proteins to ESEs promotes or stabilizes U1 binding to the 5′ splice site and U2AF binding to the 3′ splice site. Thus, spliceosome assembly becomes more efficient in the presence of SR proteins. This role of SR proteins applies to both constitutive and alternative splicing, making SR proteins both essential splicing factors and alternative splicing regulators. In contrast, hnRNP A/B proteins seem to bind to RNA and compete with the binding by SR proteins and other core spliceosome components in the recognition of functional splicing signals.

SR proteins are able to commit a pre-mRNA to the splicing pathway, whereas hnRNP proteins antagonize this process. Given that hnRNP proteins are highly abundant in the nucleus, how do SR proteins effectively compete with hnRNPs to facilitate splicing? Apparently, this is accomplished by the cotranscriptional splicing mechanism inside the nucleus of the cell (see the section earlier in this chapter titled Commitment of Pre-mRNA to the Splicing Pathway). It is thus conceivable that the transcription process can affect alternative splicing. In fact, this has been shown to be the case. Alternative splicing appears to be affected by specific promoters used to drive gene expression, as well as by the rate of transcription during the elongation phase.

Different promoters may attract different sets of transcription factors, which may, in turn, affect transcriptional elongation. Thus, the same mechanism may underlie the influence of promoter usage and transcriptional elongation rate on alternative splicing. The current evidence suggests a kinetic model where a slow transcriptional elongation rate would afford a weak splice site emerging from the elongating Pol II complex sufficient time to pair with the upstream splice site before the appearance of the downstream competing splice site. This model stresses a functional consequence of the coupling between transcription and RNA splicing in the nucleus.

19.14 trans-Splicing Reactions Use Small RNAs

In mechanistic and evolutionary terms, splicing has been viewed as an intramolecular reaction, essentially amounting to a controlled deletion of the intron sequences at the level of RNA. In genetic terms, splicing is expected to occur only in cis. This means that only sequences on the same molecule of RNA should be spliced together.

The upper part of FIGURE 19.26 shows the usual situation. The introns can be removed from each RNA molecule, allowing the exons of that RNA molecule to be spliced together, but there is no intermolecular splicing of exons between different RNA molecules. Although we know that trans-splicing between pre-mRNA transcripts of the same gene does occur, it must be exceedingly rare, because if it were prevalent the exons of a gene would be able to complement one another genetically instead of belonging to a single complementation group.

FIGURE 19.26 Splicing usually occurs only in cis between exons carried on the same physical RNA molecule, but trans-splicing can occur when special constructs that support base pairing between introns are made.

Some manipulations can generate trans-splicing. In the example illustrated in the lower part of Figure 19.26, complementary sequences were introduced into the introns of two RNAs. Base pairing between the complements should create an H-shaped molecule. This molecule could be spliced in cis, to connect exons that are covalently connected by an intron, or it could be spliced in trans, to connect exons of the juxtaposed RNA molecules. Both reactions occur in vitro.

Another situation in which trans-splicing is possible in vitro occurs when substrate RNAs are provided in the form of one containing a 5′ splice site and the other containing a 3′ splice site together with appropriate downstream sequences (which may be either the next 5′ splice site or a splicing enhancer). In effect, this mimics splicing by exon definition and shows that in vitro it is not necessary for the left and right splice sites to be on the same RNA molecule.

These results show that there is no mechanistic impediment to trans-splicing. They exclude models for splicing that require processive movement of a spliceosome along the RNA. It must be possible for a spliceosome to recognize the 5′ and 3′ splice sites of different RNAs when they are in close proximity.

Although trans-splicing is rare in multicellular eukaryotes, it occurs as the primary mechanism to process precursor RNA into mature, translatable mRNAs in some organisms, such as trypanosomes and nematodes. In trypanosomes, all genes are expressed as polycistronic transcripts, like those in bacteria. However, the transcribed RNA cannot be translated without a 37-nucleotide leader brought in by trans-splicing to convert a polycistronic RNA into individual monocistronic mRNAs for translation. The leader sequence is not encoded upstream of the individual transcription units, though. Instead, it is transcribed into an independent RNA, carrying additional sequences at its 3′ end, from a repetitive unit located elsewhere in the genome. FIGURE 19.27 shows that this RNA carries the leader sequence followed by a 5′ splice-site sequence. The sequences encoding the mRNAs carry a 3′ splice site just preceding the sequence found in the mature mRNA.

FIGURE 19.27 The SL RNA provides an exon that is connected to the first exon of an mRNA by trans-splicing. The reaction involves the same interactions as nuclear cis-splicing but generates a Y-shaped RNA instead of a lariat.

When the leader and the mRNA are connected by a trans-splicing reaction, the 3′ region of the leader RNA and the 5′ region of the mRNA in effect comprise the 5′ and 3′ halves of an intron. When splicing occurs, a 2′–5′ link forms by the usual reaction between the GU of the 5′ intron and the branch sequence near the AG of the 3′ intron. The two parts of the intron are covalently linked, but generate a Y-shaped molecule instead of a lariat.

The RNA that donates the 5′ exon for trans-splicing is called the spliced leader RNA (SL RNA). The SL RNAs, which are 100 nucleotides in length, can fold into a common secondary structure that has three stem-loops and a single-stranded region that resembles the Sm-binding site. The SL RNAs therefore exist as snRNPs that count as members of the Sm snRNP class. During the trans-splicing reaction, SL RNA becomes part of the spliced product replacing the original cap and leader (called an outron), as illustrated in the upper panel of FIGURE 19.28. Like other snRNPs involved in splicing (except U6), SL RNA carries a trimethylated cap, which is recognized by the variant cap-binding factor eIF4E to facilitate translation.

FIGURE 19.28 The SL RNA adds a leader to facilitate translation. Coupled with the cleavage and polyadenylation reactions, the addition of the SL RNA is also used to convert polycistronic transcripts to monocistronic units.

In Caenorhabditis elegans, about 70% of genes are processed by the trans-splicing mechanism, which can be further divided into two classes of genes. One class produces monocistronic transcripts that are processed by both cis- and trans-splicing. In these cases, cis-splicing is used to remove internal intronic sequences, and then trans-splicing is employed to provide the 22-nucleotide leader sequence derived from the SL RNA for translation. The other class is polycistronic. In these cases, trans-splicing is used to convert the polycistronic transcripts into monocistronic transcripts in addition to providing the SL leader sequence for their translation, as illustrated in the bottom panel of Figure 19.28.

C. elegans has two types of SL RNA. SL1 RNA (the first to be discovered) is only used to remove the 5′ ends of pre-mRNAs transcribed from monocistronic genes. How does the SL RNA find the 3′ splice site to initiate trans-splicing, and in doing so, how does trans-splicing avoid competition or interference with cis-splicing? The ability to target a functional 3′ splice site is provided by the proteins as part of the SL snRNP. For example, purified SL snRNP from Ascaris, a parasitic nematode, contains two specific proteins, one of which (SL-30kD) can directly interact with the BPB protein at the 3′ splice site. The SL1 RNA is only trans-spliced to the first 5′ untranslated region, and does not interfere with downstream cis-splicing events. This is because only the 5′ untranslated region contains a functional 3′ splice site, but it does not have the upstream 5′ splice site to pair with the downstream 3′ splice site.

The SL2 RNA is used in most cases to process polycistronic transcripts that are separated by a 100-nucleotide spacer sequence between the two adjacent gene units. In a small fraction of genes where the two adjacent gene units are linked without any spacer sequences, the SL1 RNA is used to break them up.

During processing of these polycistronic transcripts by either of the SL snRNAs, the trans-splicing reaction is tightly coupled with the cleavage and polyadenylation reactions at the end of each gene unit. Such coupling appears to be facilitated by direct protein–protein interactions between the SL2 snRNP and the cleavage stimulatory factor CstF that binds to the U-rich sequence downstream of the AAUAAA signal (see the next section, The 3′ Ends of mRNAs Are Generated by Cleavage and Polyadenylation). These mechanisms allow related genes to be coregulated at the level of transcription (because they are transcribed as polycistronic transcripts) and individually regulated after transcription (because individual gene units are separated as a result of RNA processing).

19.15 The 3′ Ends of mRNAs Are Generated by Cleavage and Polyadenylation

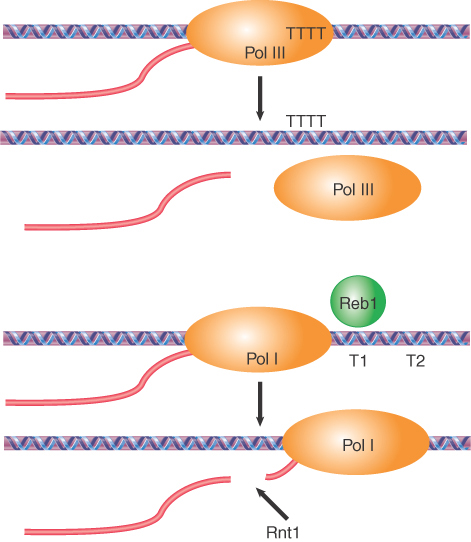

It is not clear whether RNA polymerase II actually engages in a termination event at a specific site. It is possible that its termination is only loosely specified. In some transcription units, termination occurs more than 1,000 bp downstream of the site, corresponding to the mature 3′ end of the mRNA (which is generated by cleavage at a specific sequence). Instead of using specific terminator sequences, the enzyme ceases RNA synthesis within multiple sites located in rather long “terminator regions.” The nature of the individual termination sites is largely unknown.

The mature 3′ ends of Pol II transcribed mRNAs are generated by cleavage followed by polyadenylation. Addition of poly(A) to nuclear RNA can be prevented by the analog 3′–deoxyadenosine, which is also known as cordycepin. Although cordycepin does not stop the transcription of nuclear RNA, its addition prevents the appearance of mRNA in the cytoplasm. This shows that polyadenylation is necessary for the maturation of mRNA from nuclear RNA. The poly(A) tail is known to protect the mRNA from degradation by 3′–5′ exonucleases. In yeast, it is suggested that the poly(A) tail also plays a role in facilitating nuclear export of matured mRNA and in cap stability.

Generation of the 3′ end is illustrated in FIGURE 19.29. The RNA polymerase transcribes past the site corresponding to the 3′ end, and sequences in the RNA are recognized as targets for an endonucleolytic cut followed by polyadenylation. RNA polymerase continues transcription after the cleavage, but the 5′ end that is generated by the cleavage is unprotected, which signals transcriptional termination (see the next section, 3′ mRNA End Processing Is Critical for Termination of Transcription).

FIGURE 19.29 The sequence AAUAAA is necessary for cleavage to generate a 3′ end for polyadenylation.

The site of cleavage/polyadenylation in most pre-mRNAs is flanked by two cis-acting signals: an upstream AAUAAA motif, which is usually located 11 to 30 nucleotides from the site, and a downstream U-rich or GU-rich element. The AAUAAA is needed for cleavage and polyadenylation because deletion or mutation of the AAUAAA hexamer prevents generation of the polyadenylated 3′ end (though in plants and fungi there can be considerable variation from the AAUAAA motif).

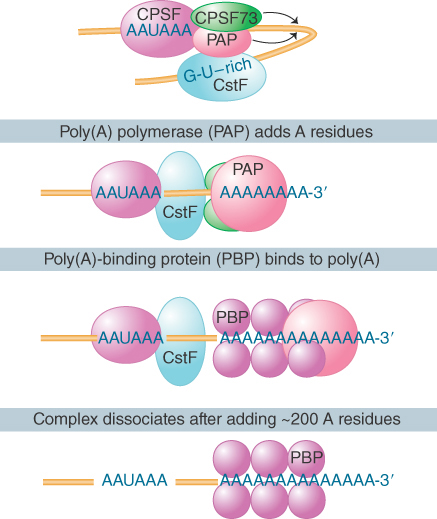

The development of a system in which polyadenylation occurs in vitro opened the route to analyzing the reactions. The formation and functions of the complex that undertakes 3′ processing are illustrated in FIGURE 19.30. Generation of the proper 3′ terminal structure depends on the cleavage and polyadenylation specific factor (CPSF), which contains multiple subunits. One of the subunits binds directly to the AAUAAA motif and to the cleavage stimulatory factor (CstF), which is also a multicomponent complex. One of these components binds directly to a downstream GU-rich sequence. CPSF and CstF can enhance each other in recognizing the polyadenylation signals. The specific enzymes involved are an endonuclease (the 73-kD subunit of CPSF) to cleave the RNA and a poly(A) polymerase (PAP) to synthesize the poly(A) tail.

FIGURE 19.30 The 3′ processing complex consists of several activities. CPSF and CstF each consist of several subunits; the other components are monomeric. The total mass is more than 900 kD.