The first sheepdogs, as described by the earliest historians and observers, were primarily guardians of the flocks. In some places, livestock guardian breeds still work with shepherds in this way, without herding dogs, but in many areas shepherds and cattlemen began to utilize dogs more specifically to help control their flocks and herds. Droving dogs were needed to drive stock long distances to distant pastures or to market. Boundary work, sometimes known as a “living fence,” became very important as shepherd and dog needed to keep their animals from encroaching on planted fields and other property. This style of herding is still used in areas of open grazing.

Enhanced strong-eyed behaviors, a hallmark of the Border Collie, did not emerge until the late nineteenth century in Britain, following the movement to open up large grazing lands by the removal of small crofters. After the eradication of serious predators, sheep could be left alone on open, rugged grazing. Neither human shepherds nor livestock guardian dogs were required on a daily basis, but dogs were needed to collect and gather often skittish sheep over large areas. This type of herding, sometimes called “fetching,” eventually traveled around the world with the Border Collie and now dominates herding competitions in many areas.

A number of different dogs and herding abilities made their way with colonists to North America, Australia, and New Zealand. When they fit into the shepherd or cattleman’s needs, they took hold. At other times, new breeds were forged to fit the new situations. The herding dog is still needed on farms and rangelands, but he is also now valued for his high intelligence and degree of trainability.

The process of domestication and selective breeding by shepherds and cattlemen over several centuries shaped the differences seen among the many breeds in this group. Because they have been developed to meet specific terrain, stock, and husbandry needs, herding dogs tend to vary in appearance, temperament, and behavior more than the livestock guardian breeds.

Size is variable but herding dogs are generally medium sized, weighing as little as 20 to 25 pounds up to 50 pounds. Herding dogs generally stand 18 to 26 inches tall. The exceptions include the corgis and some heelers, who are actually medium-sized dogs with short legs. Truly large herding dogs, weighing 70 to 80 pounds, are unusual and were developed for specific jobs.

These dogs also display a wide range of colors and patterns. A working dog is not often judged by his color, although owners may have preferences. Herding breeds have coats that are short, smooth, rough, long, and even corded. Coat choices often reflect the weather and environment of a breed’s homeland. Ears are most often erect, pricked, or folded over, and only occasionally hanging. Tails are sometimes naturally bobbed or docked but often long. Curled tails are only found in the Nordic dogs that herd, reflecting their close relatives, the spitz dogs.

Segments of the predatory sequence that were present in all the early dog ancestors (search/stalk/chase/bite and hold/bite and kill/dissect/consume) have been amplified or suppressed over centuries of domestication and selective breeding. In herding dogs, the strong search, called “eye,” and the crouch of stalking behavior can be very pronounced. Chasing is certainly an important behavior, as is biting and sometime holding in some breeds; however, the act of killing has been suppressed.

Herding breeds were developed in response to the need to keep a group of animals together by circling or by nipping. This instinct lies in the hunting behavior of the proto-wolf pack, in which some members function as headers, who race ahead of the fleeing prey to turn it back or stop it, while others worked as heelers at the back of the herd, preventing escape. Dogs can be strong eyed or loose eyed or somewhere in between (medium eyed). Most dogs are gatherers, and can be either loose- or strong-eyed. Some are more driving breeds, while others came from tending roots. (See Different Herding Behaviors.)

Herding dogs use several inherited traits or instincts in their work — eye, grip, bark, power, intensity, energy or drive, balance, and savvy. Most important, though, all herding dogs are intelligent and biddable. They are willing and eager to please their owner in carrying out their jobs. The way in which these behaviors work together in specific ways and strengths is called “style.” The various combinations and strengths of these traits distinguish one breed from another. Many versatile breeds can perform more than one style and function, and can work with different animals as well.

All herding breeds demonstrate the following characteristics and behaviors in various combinations and strengths.

Intelligence. The cleverness and intelligence of the herding dog demands careful attention in training so that the dog learns exactly what is wanted rather than what is not. It is easy to accidently teach unintended associations to these dogs. These breeds like routine, order, schedules, and enforcing rules. They may try to ensure that other family dogs follow the rules as well. Easily bored, they are independent thinkers who can solve problems or devise their own activities, which can sometimes be troublesome.

Willingness and trainability. Herding dogs are biddable, meaning they are willing and eager to please their owners. Usually affectionate and loyal, they enjoy their owners’ company and bond easily to a regular handler. They like to learn and are easy to motivate, making them good performers in work and dog sports. Alert to nuances of body language, they focus intently on their handlers and look for direction. Herding dogs can make great workday companions. They tend to follow their handler from place to place, even in the house. Some don’t like their family scattered within the house or for people to leave, and can suffer from separation anxiety.

Eye. Herding dogs watch and follow their stock, using their gaze to help move them. Strong-eyed dogs stare intensely and continuously. A strong eye is often accompanied by a crouching stance. Loose-eyed dogs survey the animals, watching for individuals that may bolt or stray. This is usually accompanied by an upright stance. Medium-eyed dogs can make strong contact but don’t do so continuously, which reduces the pressure on the animals. These dogs may have some crouch.

Grip. Herding dogs use gripping, biting, or heeling as an important part of their job. A dog who is willing to nip or bite at its charges has grip. A heading dog grips at the nose or top of the head. A heeling dog grips low on the leg or heel, ducking to avoid kicks. Heading or heeling is inherited. Gripping elsewhere on the body is inappropriate and this may also be inherited.

Puppies need to be raised with an understanding of the appropriate or acceptable use of this trait, although the instinctual urges to herd, to chase, to gather, and to control cannot be completely trained out of a herding dog. Dogs with strong herding instincts can be difficult in families with small children, since the dogs can respond to running play with a need to chase and stop it.

Bark. Many of these breeds use voice or bark to help to control or move animals. This is an inherited behavior and part of their job, although herding dogs also bark during play and out of excitement.

Power. Herding dogs project power; a sense of authority is how they make their livestock move. They are courageous, don’t back down, and may use their bodies to enforce their desires. This can make them bossy or pushy and sometimes unwilling to defer to you. This is another reason they need obedience training.

Intensity. These dogs have great focus and concentration. The stare and stalk of a strong-eyed dog can actually be somewhat unnerving. While some breeds are more laid-back when not working, others can be obsessive workaholics. Lacking an activity to focus on, they can become fixated or compulsive on certain behaviors.

Energy or drive. Herding dogs can work hard and have great endurance, sometimes to the point of exhaustion. Short walks and spending time alone in a small yard are not sufficient for most of these dogs. Some breeds need at least two hours of attention and exercise every day. Agile and athletic, these dogs are fast, accurate, and good judges of distance. They are also able to make quick turns and sudden stops.

Their need to be active extends beyond physical exercise; they must be challenged mentally and have work to do. Without sufficient stimulation and exercise, these dogs are often frustrated or destructive and can develop obsessive behaviors. Most breeds are also very tenacious and don’t want to stop playing or working. Engaging in bursts of energetic play on their own is common.

Balance and savvy. These traits also come from the proto-wolf ancestor, who had to position himself the optimum distance from his prey, sensing how they would move, before forcing them to his will.

The Border Collie’s “clap” or “crouch” to the ground is predatory stalking behavior directed in support of herding.

This New Zealand Huntaway exemplifies the energy and athleticism of the herding dog breeds.

Dogs may perform more than one type of work.

Driving. Working or pushing from close behind the stock, the dog may use body, bark, grip, and loose-eyed behaviors.

Droving. The dog works from behind, to the sides, or in the front to take animals to market or along roads.

Fetching. Sent out to gather animals and return them to a shepherd, the dog usually works at some distance from the animals and may exhibit strong-eyed behaviors.

Tending or boundary work. Watching and keeping a flock within a certain grazing area, with the supervision of a shepherd, the dog usually works close to stock. Tending is more common in unfenced grazing areas. Breeds used for this work can be more protective.

A strong-eyed dog stares intensely and stalks animals in a crouching manner. Strong-eyed dogs, exemplified by the Border Collie, tend to work stock from a distance and want to stop the motion of stock.

A loose-eyed dog, like the Australian Kelpie, uses his body to control animals and works upright without staring or crouching. These dogs want to keep stock moving and are comfortable working in close quarters.

In addition to the diversity of size, coat, and activity levels, there are distinct differences in herding styles among the breeds. Some breeds are more suitable for different kinds of stock, as well as the geography and climate of a specific area. Some breeds are also more relaxed in the home, while others are powerful, even fixated, workers.

Herding breeds can be specialists with particular instincts and aptitudes for specific stock and work. Some breeds are more adaptable and versatile. Breeds cannot be completely categorized of course — herding is a complex activity and individual dogs are capable of learning different skills and behaviors — but, in general, breeds possess specific combinations of instinctual behaviors, as well as strengths and weaknesses.

Historically, herding breeds were developed for precise needs with specific stock in a particular geography and in a particular method of agriculture. Knowing the specifics of this history and purpose can help you select the most appropriate breed for your needs and, then, the best way to train him.

Assess the role your dog will serve: full-time working dog, part-time herding or stock dog, general farm help, or primarily a family companion. Do you have an interest in competitive sheepdog trials or more casual herding activities? Do you plan to use this dog in performance events or dog sports? Or do you want a dog who will enjoy a moderately active life? Consider your real needs and how this dog will fit into your family, and then choose an appropriate breed.

Some herding breeds are definitely more relaxed, all-purpose dogs than others, which is also an important consideration if you are looking for a general farm dog or family companion. Some breeds are capable of working steadily all day; others are able to perform hard or fast work; while others tend to be rather laid-back until asked to help. Some breeds are more dominant and territorial, which can be helpful if you want a general farm watchdog as well, while others are very friendly and accepting of strangers.

Consider your stock. Are your sheep or goats fast and nimble, flocking or nonflocking, spooky or accustomed to daily handling? Do you have dairy cattle or ranch cattle? Some herding breeds are suited to working cattle or hogs, while others can adapt to the variety of animals found on a small farm. Turkeys, geese, or ducks pose particular challenges.

Consider your husbandry practices. Do you utilize large or small pastures? Open range or feedlots? Do you actively shepherd with your dog daily or only occasionally? Do you use more than one dog? Will your dog need to deal with extremes of weather?

For a part-time worker and general farm helper, very strong working abilities can definitely be problematic. Many people who need such a helper dog find the less intense and energetic breeds are a better fit, as these dogs can be content with an active family life as well. In a purely family situation, the strong presence of working ability in a pedigree may not be important. In fact, strong herding dogs are often not the best choice for a companion dog who may not ever be asked to herd.

Certain breeds have specific issues. Several herding breeds — Australian Shepherds, Collies, Border Collies, and others — have a genetic mutation that causes multidrug resistance (MDR). Dogs can be tested for this condition. If your dog is a carrier or his status is unknown, you should use great caution with certain drugs, including antibiotics, antiparasitics, antidiarrheals, heart medications, Ivermectin, and steroids. Reputable breeders also check for issues such as collie eye anomaly (CEA), progressive retinal atrophy (PRA), congenital deafness, and hip dysplasia (HD). Congenital deafness can be linked to specific pigmentation patterns, such as merle and white coats, often found in the herding breeds.

Hardworking herding dogs are also susceptible to dehydration, overheating, and heat exhaustion, as well as various work injuries.

Unless you are experienced with herding dogs, it is a good idea to look for a pup that is moderate or average in terms of temperament. Avoid the extremes, which can pose additional challenges in handling and training. In some breeds, divisions have developed between working and show lines.

Pay attention to coat quality, as there can be a difference between a show or glamour coat and a weather-resistant work coat that sheds dirt. Some breeds occasionally produce “fluffy” pups with coats that are too soft and long to be practical in the field and unacceptable for a show ring; although they can be fine for a companion owner who doesn’t mind the extra grooming. Unless you are planning to show or breed, mismarked coats or similar issues are unimportant.

In some breeds, including Australian Shepherds, different lines have been developed. Dogs bred primarily for show may differ in conformation from working dogs or demonstrate a lack of working aptitude.

Temperament is very important in a herding dog. A good breeder who has carefully selected the parents and observed the litter can be relied upon to provide good recommendations about a pup’s behaviors, instincts, and tendencies. Your breeder can also help you determine whether a pup is softer or harder in nature. Dogs with either tendency can be good workers, but owners often prefer one or the other and the dog’s nature also determines how you train. Very hard or dominant dogs can be dedicated workers but are often not as suited to herding trials or dog sports without an experienced handler. More aggressive or pushy pups may need an experienced trainer. Highly independent dogs can be less eager to please and harder to motivate. Dogs that are somewhat submissive often follow your direction and leadership well.

There can also be differences between males and females as working dogs. Males may be stronger and larger, which can be important in some working situations. Males can also be harder and more independent. Females can be more biddable, sensitive, and soft in temperament. Again, though both are good workers, some owners and handlers have a preference.

Whether you are looking for a full- or part-time worker or a family companion, look for a pup who is

Avoid a pup who is

Histories and descriptions for herding breeds frequently state that these dogs also guarded the flock. This is a misconception of the herding dog’s role. Herding dogs actively worked with shepherds in unfenced grazing or were sent out to fetch animals and return them to the shepherd. They were not left alone with the animals 24 hours a day, like a livestock guardian dog.

In many areas and among some transhumant peoples, herding dogs traditionally worked in partnership with the larger livestock guardian dogs and the shepherds. They might sound an alarm to alert the shepherd or run off a roaming dog, but they left predator control to the guardians. When he was not working, the herding dog was at the feet of the shepherd. There is a tremendous difference between a watchdog and a guardian. Herding dogs are alert and vocal; they sound an alarm at a threat or disturbance. They may even charge or attack a threat. However, most herding breeds are not large enough to successfully confront large predators or packs of predators.

True herding dogs lack the placid, watchful nature of an LGD. They have powerful instincts to chase, gather, and fetch, even if not given instructions to do so. Roaming or unsupervised herding dogs often cause tremendous damage to a flock of sheep, worrying or running them to death.

Many herding dogs can find a fulfilling role even without having daily contact with livestock, if they have an appropriate outlet for their energy and drive. Both working farm dogs and family companions can participate in the following activities.

Herding breeds excel at the following activities, all of which have local and national organizations that are easily found online.

Games are not only useful training tools for young herding dogs, they are great outlets for adult dogs as well.

Although herding dogs need to reach maturity before their true working abilities and style are revealed, you can perform some basic instinct testing on a pup. Because herding instincts are so strongly inherited, however, one of the best indicators of potential is the herding ability of the parents and other dogs in the pedigree. Are the parents and older siblings working? Temperament and physical soundness are also very important in a working dog. If you are looking for a serious working or competitive trial dog, watching the parents work, in person or via video, is extremely valuable.

Pups as young as four or five weeks can be introduced to ducks or young lambs with careful supervision. This is best done by someone knowledgeable about herding behaviors — the signs can be very subtle. It is sometimes possible to see the early presence of eye or crouching; gripping or heeling; attentive watching; chasing or following; desire to keep the group together; heading; and balance or distance. It is also true that some pups show very little interest in herding until they are older but go on to become good working dogs.

More serious tests of herding instinct need to wait until the pup is older, beginning at about six months, when early training can also begin. Earlier controlled exposure to stock is also helpful to a young pup. Your puppy can learn basic obedience tasks before then, some of which are introductions to herding commands. Some training games are also beneficial.

Consistency and precision in handling any puppy is important, but especially so with herding breeds. If this is a working dog, decide who will handle and train it. Make certain other family members do not use conflicting commands or behaviors with the pup. Herding dogs are very smart. They can distinguish between many commands with varying verbal emphasis combined with body language and gestures, but they can become confused over similar commands given in slightly different ways or with different expectations.

The new pup needs to have his own place to sleep, hang out, and eat. Establish boundaries and expectations early. If you expect him to live outside, start him out there rather than changing his situation later. Socializing to people, experiences, and other animals or pets is definitely important. If he is going to work with birds or stock later, he needs to become socialized to them as well.

Basic obedience training — sit, down, stay, and a reliable recall — is required. To continue more formal herding training, consult a good training book or work with an experienced mentor in order to teach commands appropriately and with good word choices. Handlers have different word preferences, as well as slightly different meanings, for specific commands, and may choose words that don’t sound alike for different commands. Some handlers also use whistle commands, which you can begin in early training.

Herding dogs respond best to kindness and patience, not heavy-handed training methods. Consistency and encouragement are necessary to build a confident and courageous dog. The building of a trusting relationship between handler and dog is all-important.

AKC Herding Program — arena trials (recognized AKC herding breeds)

American Herding Breed Association — tests and trials

Australian Shepherd Club of America — arena tests and stock-dog trials open to all breeds, including a noncompetitive Ranch Dog Program, with all-around herding, including driving

Australian Sheep Dog Worker’s Association

Canadian Border Collie Association — primarily Border Collie

International Sheepdog Society in — primarily Border Collie

New Zealand Sheep Dog Trial Association

US Border Collie Handler’s Association — primarily Border Collie

Verein für Deutsche Schäferhunde (SV) — primarily German Shepherd tending style

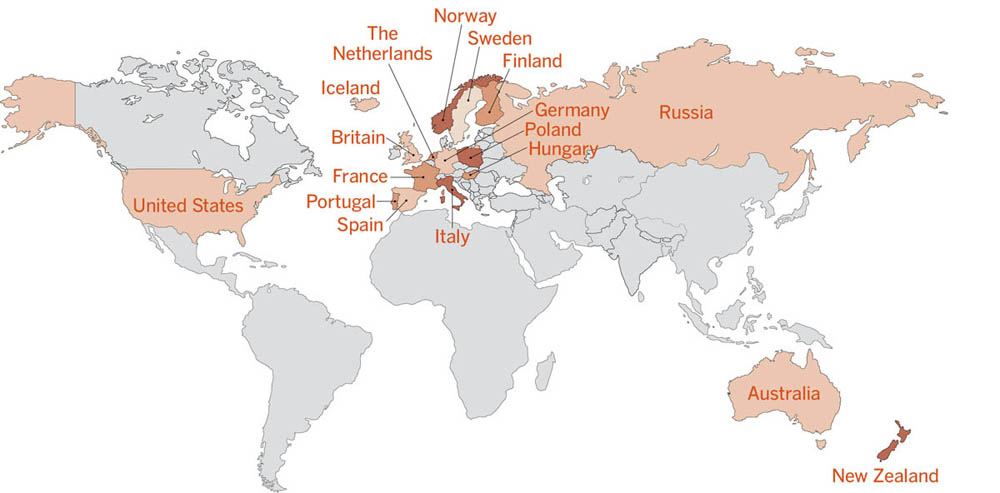

Double-tap the map to open to fill the screen. Use the two-finger pinch-out method to zoom in. (These features are available on most e-readers.)

| Australia | Italy |

| Australian Cattle Dog | Bergamasco |

| Australian Kelpie/Working Kelpie | Bouvier des Flandres |

| Australian Koolie | The Netherlands |

| Australian Shepherd | Dutch Shepherd |

| Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog | Schapendoes |

| Britain | New Zealand |

| Bearded Collie (Scotland) | Huntaway |

| Border Collie (England, Scotland, Wales) | Norway |

| Rough and Smooth Collie (Scotland, England, Wales, Ireland) | Norwegian Buhund |

| Shetland Sheepdog (Scotland, England) | Poland |

| Cardigan and Pembroke Welsh Corgi (Wales) | Polish Lowland Shepherd |

| Lancaster Heeler (England) | Portugal |

| Finland | Portuguese Sheepdog |

| Finnish Lapphund | Portuguese Water Dog |

| France | Russia |

| Beauceron | Samoyed |

| Berger Picard | Spain |

| Briard | Catalan Sheepdog |

| Pyrenean Shepherd | Sweden |

| Germany | Swedish Lapphund |

| German Shepherd | United States |

| Hungary | Australian Shepherd |

| Mudi | Louisiana Catahoula Leopard Dog |

| Puli | Hangin’ Tree Cowdog |

| Iceland | English Shepherd |

| Icelandic Sheepdog | Texas Heeler |

| McNab Dog |