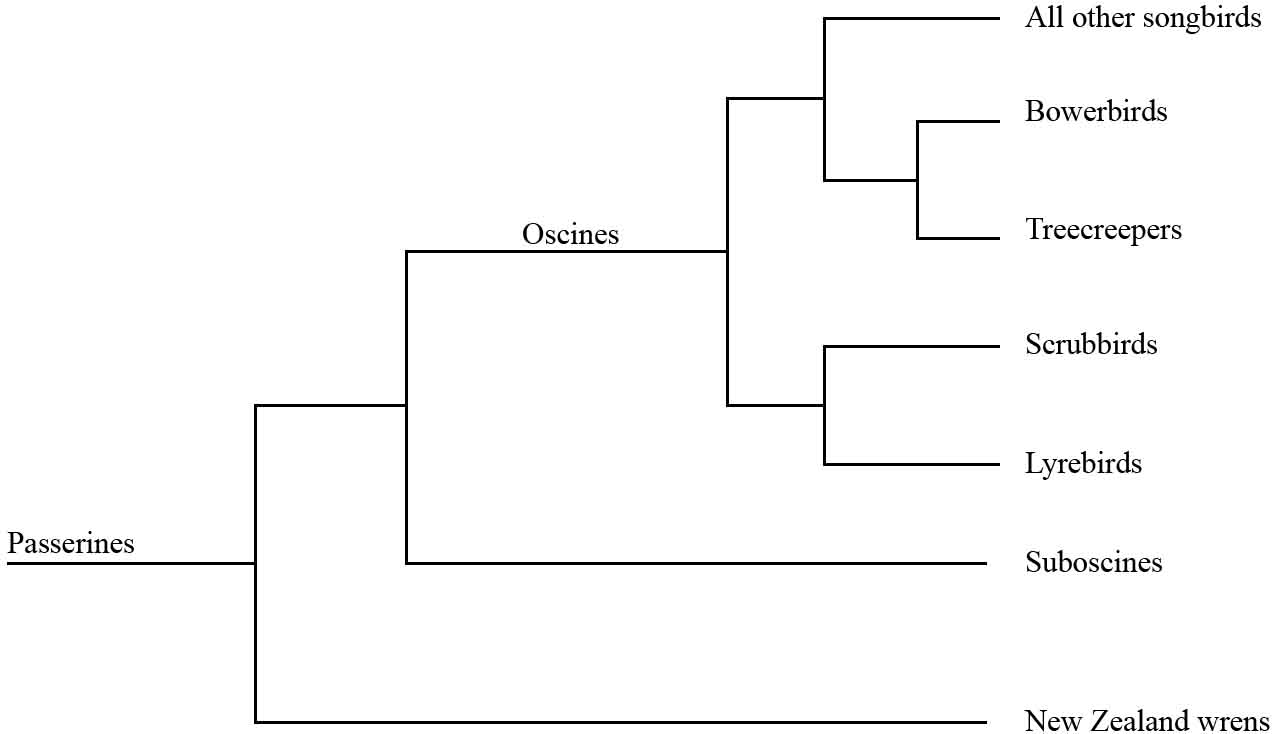

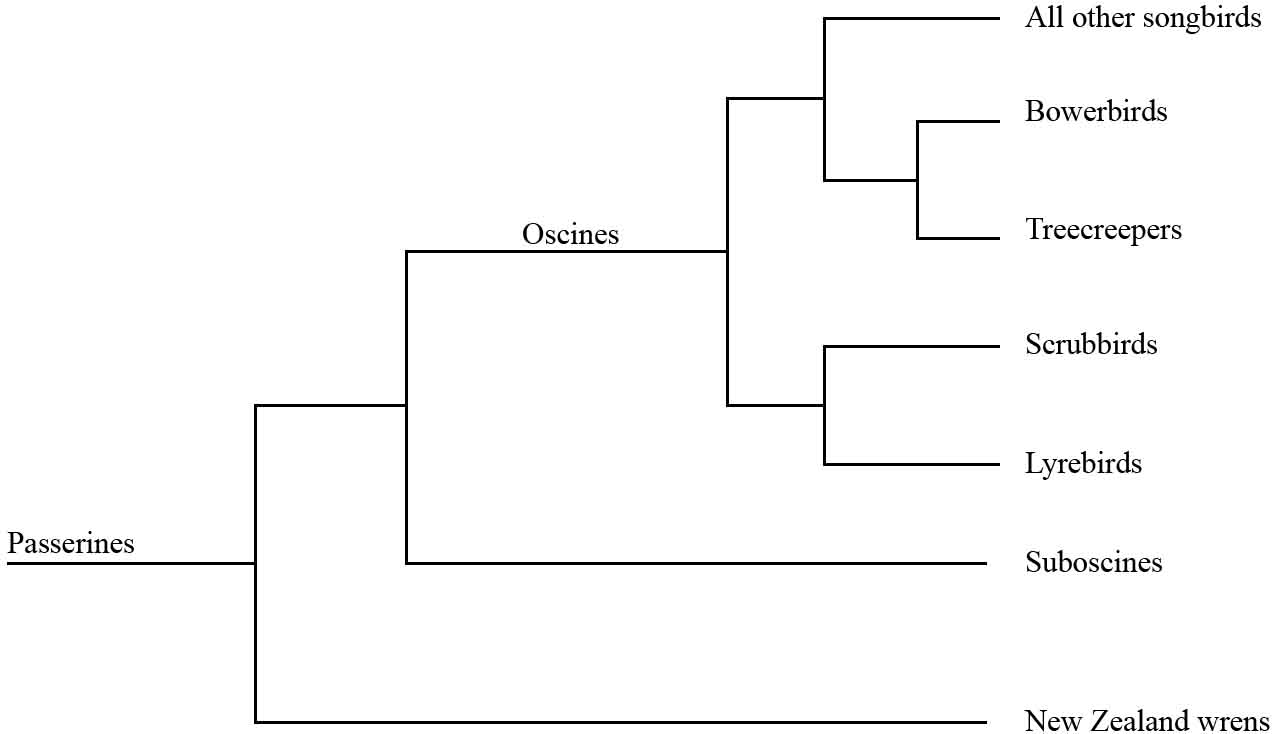

Figure 17.1 The basal passerines. After the New Zealand wrens diverged, the passerines split to produce the suboscines and oscines (songbirds).

On Christmas Eve, 1961, the Australian naturalist Vincent Serventy was at home making his last-minute festive preparations, when the phone rang. It was a reporter from the West Australian newspaper who sought his views on the reported rediscovery of the Noisy Scrubbird. Serventy’s reply – ‘If it’s true, it’s the most exciting find of the century’ – encapsulates one of the most dramatic episodes in Australian ornithology.1 Indeed, the finding of the scrubbird (family Atrichornithidae) so excited the general public that its loud call was aired on radio stations throughout the world.

The story of this Lazarus species began in May 1838, when the English ornithologist and renowned artist John Gould travelled to the continent to collect material for his monumental tome Birds of Australia. Among his entourage was the naturalist, explorer and taxidermist John Gilbert, whom he sent out to remote areas to seek new botanical and zoological specimens. On 3 November 1842, while working at Drakesbrook on the southwestern tip of Australia, Gilbert first heard and eventually collected a bird unknown to science: the Noisy Scrubbird (or jee-mul-uk according to the local Aborigines). The skins of four individuals, together with many other species, were forwarded to Gould the following year, accompanied by a letter that included the following account of the new find:

This is without exception the loudest of the Western Australian songsters I have yet heard. It inhabits the densest and rankest vegetation, on the sides of hills and thick swamp grass on the banks of small running streams or swamps, and is of all birds, the most difficult I have yet had to procure … as it runs with the utmost rapidity on the ground, sheltered from view by the overhanging vegetation which renders it almost impossible to get a shot at.2

Gould showed keen interest in the skins of the ‘noisy bird’ and noted, ‘few of the novelties received from Australia are more interesting than the species to which I have given the generic name of Atrichia.’3 Gould’s English name, Noisy Scrubbird, has remained, although his original generic name was later found to be already in use, so it was subsequently altered to its present spelling: Atrichornis. Surprisingly, the usually meticulous artist-entrepreneur paid scant regard to Gilbert’s accurate description, and his published illustration portrays a pair of birds perched on leaf-adorned branches, rather than on the ground.3 Twenty years later, in the 1860s, the energetic Australian George Masters, an excellent shot who caught venomous snakes with his bare hands, obtained seven further specimens, and then another collector took eight birds in the 1880s.

The Noisy Scrubbird was last seen in 1889 and remained lost, but not forgotten, until it was rediscovered in 1961. In December of that year, Harley Webster, headmaster of Albany High School and a keen birdwatcher, was attracted by an unfamiliar birdsong at Two People’s Bay, south of Perth:

I came away that evening with impressions of a brown bird with a call that really made my ears ring and with the knowledge that it was almost certainly the Noisy scrub-bird.4

After extensive field work, Webster found several birds, although a nest eluded him. Like most birders who have seen the scrubbird, I can vouch for the difficulties faced by Gilbert, Masters and Webster. While I was staying at Cheynes Beach near Albany, the unmistakable song of a male scrubbird was heard coming from an area of dense scrub near the shoreline. Despite a patient wait of nearly an hour, the bird remained hidden, even though it could not have been more than 5 metres away. Then, without warning, a rat-like apparition scuttled across the track and vanished into the thick undergrowth on the other side, where it proceeded to tease me once again with its ear-piercing call. Although I never managed another sighting, I nevertheless cherish my 3-second, full-frame view of this notoriously difficult bird. Today, only around 1,000 adults remain, and despite an intensive conservation programme, including fire protection, habitat management and translocation to new sites, the species remains threatened.5

In 1866, a second member of the Atrichornithidae, the Rufous Scrubbird, was described by the Australian zoologist Edward Ramsay. It is also rare, and inhabits a few areas of rainforest on the eastern slopes of the Great Dividing Range along Australia’s east coast, some 3,000 kilometres from its cousins. Ramsay was struck by the bird’s ventriloquial powers and noted that ‘they must be heard to be believed.’6 Like the Noisy Scrubbird, the Rufous Scrubbird inhabits impenetrable undergrowth, creeps and runs along the ground like a rat, and feeds on invertebrates found among the leaf litter.

Lyrebirds (family Menuridae) are also exclusively Australian, and are renowned for their remarkable displays and use of mimicry (see The Zebra Finch’s Story). Specimens were much easier to obtain than those of scrubbirds, and several skins had already reached European naturalists by the end of the eighteenth century. In 1800, a British Army officer, Thomas Davies, presented the first description of Menuridae – the Superb Lyrebird – to a scientific meeting of the Linnean Society in London (Plate 23). The English name ‘lyrebird’ reflects the male’s spectacular tail, consisting of 16 highly modified feathers that were originally thought to resemble a lyre. Such a misunderstanding occurred when an early specimen was prepared for display at the British Museum by a taxidermist who had never seen the bird in the wild. As a result, he incorrectly placed the tail’s feathers in an upright position, similar to that of a peacock during a courtship display. Later, John Gould reinforced this view when he painted the lyrebird in a similar pose, using the museum’s exhibit as his model. In fact, the male lyrebird inverts the tail over his head and neck during courtship displays and fans the feathers to form a silvery-white canopy.

The only other species of lyrebird, the Albert’s Lyrebird (named in honour of Prince Albert), is smaller and rarer than the Superb Lyrebird and was not described until 1860. It has one of the smallest distributions of any bird on the Australian continent, being confined to small scattered areas within southern Queensland and northeast New South Wales. Its total population is estimated at only 3,000–4,000 breeding birds, and the species remains under threat since its fragmented distribution and sedentary nature renders gene flow between populations unlikely. Any environmental disaster, such as a severe regional drought, has the potential to affect every individual.

Figure 17.1 The basal passerines. After the New Zealand wrens diverged, the passerines split to produce the suboscines and oscines (songbirds).

What the early collectors could not know was that scrubbirds and lyrebirds are closely related, and that both families lie at the base of the entire phylogenetic tree of the songbirds (Figure 17.1). They are ancient sister groups to all the other oscines. As we will discuss, this finding turns out to be crucial in the search for the origin of the world’s songbirds, or, as Tim Low poetically puts it, the land ‘where song began’.7

Erosion of northern-centric certainty

The Australian passerines were discovered many years after European ornithologists had classified most of the world’s species. It is not surprising, therefore, that when Victorian adventurers and species hunters dispatched their large collections of skins back home, taxonomists were content to accept that many belonged to families already well defined, including wrens, thrushes, treecreepers and flycatchers. Novel species from down-under were seen as ‘the poor last gasp of radiations that had been accumulating over eons in the Old and New Worlds … relatively recent derivatives of corresponding groups better known and already described from Eurasia and the Americas.’8 Personality and emotion play a surprisingly large role in science, and the unwavering support for the ‘northern-centric’ view by Ernst Mayr, a tower of twentieth-century evolutionary biology, influenced many scientists of his generation. In an article entitled ‘Timor and the colonization of Australia by birds’ (1944), Mayr expounded with typical authority that Australia had received its birds in waves from Asia.9 The first to arrive were the early emus, lyrebirds and honeyeaters, to be followed later by the ancestral robins and treecreepers. This northern-centric view even withstood the challenge offered by Australasia’s many endemic families: scrubbirds, lyrebirds, bowerbirds, birds-of-paradise and logrunners. As Michael Heads emphasises, New Guinea’s avifauna was seen traditionally as ‘a sink, made up of waifs and strays that arrived from elsewhere in recent Neogene times.’10 In other words, for over 150 years the ancestral home of all songbirds was thought to be located in the northern hemisphere. It is against this backdrop that the full impact of the latest data can be appreciated. For recent molecular studies and fossil finds have literally, and metaphorically, turned the world of oscine evolution upside down.

As we have discussed, it was the brilliant and mercurial Charles Sibley who first challenged conventional wisdom when he compared species’ DNA rather than their morphological traits. Such novel approaches to systematic biology relied on the unique binding behaviour of DNA: single-stranded molecules bind, or hybridise, more tightly to themselves than to less similar strands. Sibley realised that genetic material would bind best between individuals of the same species, less well between closely related species, and least of all between species from different families. By determining the strength of DNA binding between any two species, a phylogenetic tree can be constructed whose branching points mirror the recency of common ancestry. Working with his colleague Jon Ahlquist between 1975 and 1986, Sibley analysed 26,000 DNA–DNA interactions from 1,700 hundred species, representing all the avian orders and most of the recognised families. The results were startling: the endemic passerine families of Australia and New Guinea (scrubbirds, bowerbirds, lyrebirds and Australasian treecreepers) were more closely related to each other than to the passerines of Eurasia. Sibley and Ahlquist concluded that such endemics must have ‘arisen within the area and were not the products of a series of invasions from Asia.’11 Their findings suggested, for the first time, that Australia may have had a significant role in songbird evolution.

Several years later, a young Melbourne graduate, Les Christidis, teamed up with fellow Australian Richard Schodde to check Sibley’s findings. They adopted a slightly different approach. Rather than compare species’ genetic material directly, they studied the encoded proteins, or enzymes, extracted from the songbirds’ liver, heart and muscle. By analysing the behaviour of these proteins in electrophoretic gels, they were able to construct phylogenetic trees: the greater the protein separation, the greater the difference in gene sequence, and the greater the evolutionary distance. What they found contrasted with the prevailing dogma and required the entire oscine family tree to be redrawn. In contrast to Sibley’s study, the protein approach showed the Old World songbirds to be nested entirely within the Australo-Papuan songbirds. This finding implied that all Eurasian passerines, including our familiar starlings, thrushes and sparrows, must have evolved from ancestors that inhabited the southern hemisphere. Furthermore, the two lyrebirds occupied the most basal position and therefore had the longest evolutionary history – likely remnants of an ancestral population from which all the other oscines arose.12

At that time, a southern origin of songbirds was not accepted by the scientific community, and the authors had difficulty getting their results published. After several years of rejection, their paper finally appeared in the British Ornithologists’ Union’s journal Ibis, although with an imposed watered-down conclusion to avoid controversy.13 The final paragraph, while understandably vague, was nevertheless profound in its implications:

It is not beyond reason to draw attention to the possibility of a Gondwanan origin for the order … Although purely speculative at present, this hypothesis does warrant testing.12

The Australians’ conclusion is a classic example of how science can pan out in unexpected ways: a ‘paradigm shift’ in biological thought that lends credence to Thomas Kuhn’s view of scientific revolutions.14 Except, in this case, the paradigm shift was overlooked for nearly 10 years, until the publication of confirmatory evidence.

The above outcome seems odd in hindsight, since a detailed morphological study published much earlier had hinted at the same conclusion. In 1982, Alan Feduccia and Storrs Olson noted that while lyrebirds are oscines, their bone structure, including that of the stapes, is more primitive than that of other songbirds, including the bowerbirds and the birds-of-paradise. In fact, the bones appeared most similar to a family of South American suboscines: the tapaculos. Their prescient conclusion – that the passerines ‘probably arose in the southern hemisphere’ – was ignored, and their findings languished in the recondite tomes of the Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology.15

It was not until 2002 that the scientific argument was settled once and for all. Two independent groups, one led by Keith Barker at the American Museum of Natural History and a second headed by the Swede Per Ericson, compared gene sequences from a selection of oscines.16 Despite using different genes, the results were the same: lyrebirds lie at the base of the oscine tree and, as a result, are the most primitive of all songbirds. However, the phylogenetic position of the scrubbirds remained unresolved, as neither Barker nor Ericson had suitable DNA for study. One might have predicted, given field observations and Sibley’s early DNA–DNA hybridisation studies, that scrubbirds and lyrebirds would turn out to be closely related and that their ancestry would be similar. Both families, for example, are excellent mimics, have the same volume of song, and possess a similar syrinx structure. Scrubbirds and lyrebirds are highly secretive and rare within their respective ranges and are primarily ground-dwellers, inhabiting similar ecological niches. Furthermore, the male scrubbirds’ display is like that of immature lyrebirds, with elongated and fanned tails, lowered wings, and a torso that quivers from the effort of their sustained, loud and melodious song. In 2007, an Australian study by Terry Chesser and José ten Have confirmed what was expected: scrubbirds are sister to the lyrebirds, and both genera are sister to all other songbirds.17

To some, the construction of phylogenetic trees, whether based on morphological traits or DNA structure, may seem a little dry and theoretical. But it is not! In the words of Keith Barker, ‘the inescapable conclusion is that songbirds had their origin on the Australian continental plate.’18 He then added ‘the only alternative is to postulate a previously widespread oscine lineage that invaded Australia many times and then went extinct with the exception of the Passerida.’ We will return to the Passerida in The Starling’s Story, but the evidence is irrefragable: songbirds first evolved in Australia.