Figure 3.1 Body Mass Index (BMI) chart

Taken from Dr Robert Povey, Dr Claire Hallas and Dr Rachel Povey, Living with a Heart Bypass, London, Sheldon Press, 2006, p. 82.

While your doctors and specialist nurses can give you the treatments to fight the cancer, eating well and keeping an eye on your nutritional health is your responsibility. Many people welcome this as a key area in which they can have some power, after feeling very much disempowered by the illness and treatment.

Your specialist team will routinely weigh you and monitor any weight loss or gain. However, it is up to you to speak up if you feel you have a poor appetite or are losing weight, if you notice that your clothes are feeling loose or you have specific difficulties eating. Alternatively, if you feel you are gaining weight you should draw it to your team’s attention. It is also important to speak up if you have noticed any side effects which are affecting your appetite or your ability to eat normally.

Don’t be misled by your current weight, even – or especially – if you are secretly relieved to have lost a few pounds. For example, you may feel that you are overweight but you may still be at risk of malnutrition, as I explain below. When tracking weight, it’s more important to look out for fluctuations rather than necessarily going by your current weight. That is, it is more important to record any trends in weight changes rather than what you actually weigh now.

Recording weight fluctuations is especially important if you were overweight when you started your treatment. Although you may feel or look as if you are currently at a healthier weight, it is still possible for your nutritional health to be compromised. This applies even if you are still at a weight that may normally be considered overweight for your height.

Quite often, people who have started treatment at a weight that would normally be considered higher than ideal are at just as much risk of nutrition or malnutrition problems as anyone else. What needs to be monitored is the amount of weight that has been lost overall, or the total percentage body weight lost over the past one to three months.

People who are overweight may still look healthy or as if they are at a normal weight. However, as their weight may have changed significantly during their treatment, the reality may be that they have lost significant amounts of lean muscle weight and the body may be struggling with the consequences of depleted nutrient stores.

In fact, poor nutritional health issues are often overlooked in someone who appears overweight. Remember to look at weight changes in the recent weeks and months, not just the weight you are at present.

Another point to bear in mind is that different kinds of cancer carry certain potential nutritional dangers. Table 3.1 provides a guide to some of the nutritional risks associated with some of the main cancer types. However, because of the enormous diversity in cancer types and treatments this can be no more than a general guide, and you should discuss any individual nutritional concerns with your doctor and treatment team.

Table 3.1 Nutritional risks associated with different types of cancer

| Cancer location | Common nutrition problems | Broad nutrition recommendations |

| Head and neck | Sore mouth Difficulties chewing and swallowing A third of people experience significant weight loss | Eat very soft food Boost energy intakes Aim for extra support feeding |

| Upper gastrointestinal tract | Sore mouth and throat Difficulties swallowing Reflux Nausea Two-thirds of people experience significant weight loss | Adopt an early build-up diet Boost energy intakes Eat small frequent meals and snacks |

| Lower gastrointestinal tract | Risk of nutrition problems depends on stage of cancer and treatments Healthy diet benefits | Fibre intakes may need to be adjusted depending on bowel function If no nutrition problems, then a healthy cancer treatment diet is recommended |

| Gynaecological (endometrial) | Risk of nutrition problems depends on stage of cancer Weight gain risk Bowel function problems | If no nutrition problems then a healthy cancer treatment diet |

| Breast cancer | Risk of nutrition problems depends on stage of cancer Weight gain risk | If no nutrition problems then a healthy cancer treatment diet |

| Prostate cancer | Risk of nutrition problems depends on stage of cancer Higher weight gain risk | If no nutrition problems then a healthy cancer treatment diet |

| Lung cancer | Risk of nutrition problems and weight loss | Eat to manage treatment side effects and boost diet as needed to help maintain a healthy weight |

| Brain/neurological tumours | Risk of nutrition problems depends on stage of cancer Higher weight gain risks due to changes in the endocrine system | If no nutrition problems then a healthy cancer treatment diet |

| Metastatic or advanced cancers of any type | High risk of nutrition problems and treatment side effects | Eat to manage side effects and boost diet with extra nourishing snacks |

Source: Adapted from Dr Clare Shaw, Nutrition and Cancer, London, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, Table 9.1.

If you have a type of cancer that is associated with nutritional difficulties or weight loss, then it becomes even more important to try to eat as well as you can. However, as I said, while it’s your responsibility to keep an eye on your nutritional health, do please remember you don’t have to do it alone. Indeed, you mustn’t – that’s what your medical care team is there for!

Here is a simple questionnaire referred to as the Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST), used by many cancer centres to help identify those at risk of nutritional problems during treatment. While a higher score doesn’t automatically mean you have nutritional problems, it does flag up those in need of a more thorough nutritional assessment by their doctor or the dietitian.

These simple screening questions should be reviewed on a regular basis, especially if you have a cancer that puts you at risk of nutritional problems or you notice weight or shape changes.

Simply answer the questions below and then add up your scores. Remember, it is just a guide; if you are concerned you should discuss your results with your doctor or specialist nurse team. If you are having problems you should ask to be referred to a cancer specialist dietitian.

1Have you lost weight recently without trying?

No: score 0.

Unsure: score 2.

Yes: answer Question 2.

2If you answered yes to Question 1, how much weight have you lost?

1–6 kg (2–13 lb): score 1.

7–11 kg (14–23 lb): score 2.

12–16 kg (24–33 lb): score 3.

More than 16 kg (33 lb): score 4.

Unsure: score 2.

3Have you been eating poorly because of a decreased appetite?

No: score 0.

Yes: score 1.

Now work out your total weight loss and appetite score.

A score of 0–1 assumes you are eating well and have not noticed any recent weight loss. Continuing and regular reviews with your team or using this questionnaire are recommended.

A score of 2–3 assumes you are having difficulties with your eating and not managing your normal approaches. It also assumes you have lost between 1 and 6 kg (2 and 13 lb). It is important you inform your team of the difficulties you may be having and request a referral to the dietitian as soon as possible.

A score of 4–5 suggests you have been having a lot of difficulty eating and have lost a large amount of weight, more than 6 kg (13 lb). It is important to contact your doctor and specialist team for immediate guidance and support. (Based on M. Ferguson, S. Capra, J. Bauer and M. Banks, ‘Development of a valid and reliable malnutrition screening tool for adult acute hospital patients’, Nutrition 15, 6 (1999): 458–64.)

If it is difficult to weigh yourself, or you aren’t quite sure how much weight you have lost, or when, then you can look for other clues such as:

•changes in where you buckle your belt;

•whether your rings are becoming loose;

•whether you can observe changes in your face;

•whether people have noticed that you may have lost weight;

•whether your eyes look a little more sunken than usual.

If you note any significant changes here, you should record this as a score of 3 or 4.

At times, the scales can be misleading, especially if you are experiencing fluid build-up (oedema or ascites) around the belly, legs or hands. This type of weight gain is not an indication of excess nutrition. In fact, quite often behind the fluid weight gain many individuals have lost fat and muscle weight, putting them at risk of nutritional health problems.

Body mass index (BMI) is a commonly used assessment to determine whether your weight is helpful to your health. It was based on American health insurance statistics and, although a useful measurement, only looks at weight and height: it doesn’t look at changes in body weight or assessment of body composition. The changes in body composition – muscle and fat – are probably the most important nutritional consideration in people who have either lost muscle or who have gained fat weight. Although a useful indicator of nutritional health, the BMI doesn’t measure shape changes.

This can be misleading, as the absolute BMI number may present someone as being at a normal weight or even a higher than ideal weight when in fact that person may be malnourished because of the total amount of weight lost since starting treatment. For example, someone who started treatment at a weight of 110 kg (244 lb, or 17.3 stone), is 1.7 m (5 ft 6 in) tall and has lost 20 kg (44 lb, or 3 stone) in the past three months would have a BMI of 31. This as an absolute measure suggests being overweight or obese; however, the loss of nearly 20 per cent of total body weight in such a short period owing to difficulties in eating would suggest this person is at a higher risk of nutritional depletion and the associated complications of malnutrition. This is why, in addition to checking the absolute weight and a BMI during the treatment period, it is equally important to put this into context against the total weight changes of recent months.

You can assess your BMI using the chart in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Body Mass Index (BMI) chart

Taken from Dr Robert Povey, Dr Claire Hallas and Dr Rachel Povey, Living with a Heart Bypass, London, Sheldon Press, 2006, p. 82.

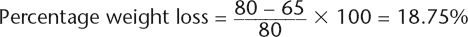

Another simple way to assess nutritional status is to look at the weight a person may have lost or gained over a certain time period as a percentage of total body weight. This will give a more accurate indication of what is happening to the body shape at the moment.

For example, if a person’s usual weight is 80 kg and six months later it is 65 kg:

This would be considered a significant weight loss, with probable nutritional consequences. Although many people might like a lower weight of 65 kg (10 stone), it is important to realize that significant amounts of unintentional weight loss are associated with reduced prognosis and nutrition-related complications.

It can also be easy to miss small amounts of weight loss. For example a 5 per cent weight loss in a 50 kg (8 stone) person is a loss of just 2.5 kg (4.5 lb). Regularly checking your weight and other measurements of nutrition status helps to ensure changes are picked up and acted upon sooner rather than later.