Meat animals may be raised and the meat cured at home for much less than the cost of purchased meat. By raising your own meat, you can ensure that the animals are raised and slaughtered humanely and can avoid the hormones and other health hazards found in most commercially raised meats.

In selecting animals for butchering, health should have first consideration. Even though the animal has been properly fed and carries a prime finish, the best quality of meat cannot be obtained if the animal is unhealthy; there is always some danger that disease may be transmitted to the person who eats the meat. The keeping quality of the meat is always impaired by fever or other derangement.

An animal in medium condition, gaining rapidly in weight, yields the best quality of meat. Do not kill animals that are losing weight. A reasonable amount of fat gives juiciness and flavor to the meat, but large amounts of fat are objectionable.

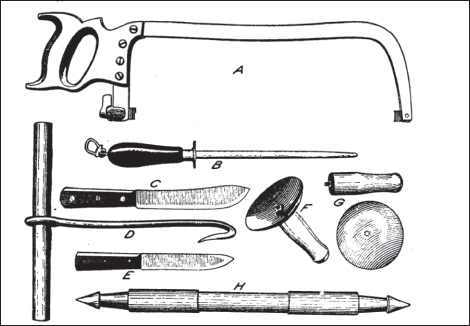

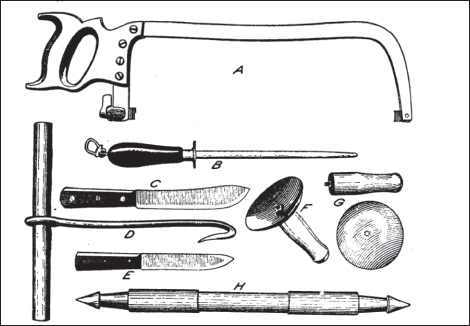

Figure 1.—Tools for killing and dressing hogs. A, meat saw; B, 14-inch steel; C, Cutting knife; D, hog hook; E, 8-inch sticking knife; F, bell-shaped stick scraper; G, separate parts of stick scraper; H, gambrel.

Figure 1.—Tools for killing and dressing hogs. A, meat saw; B, 14-inch steel; C, Cutting knife; D, hog hook; E, 8-inch sticking knife; F, bell-shaped stick scraper; G, separate parts of stick scraper; H, gambrel.

The breeding of animals plays an important part in producing carcasses of high quality. Selection, long-continued care, and intelligent feeding will produce meat of desirable quality. Smooth, even, and deeply fleshed hogs yield nicely marbled meats.

The meat from young hogs or cows lacks flavor and is watery, and that from old hogs generally is very tough. However, if older animals are properly fattened before slaughter, the meat will be improved. Hogs or cows may be killed for meat any time after eight weeks of age, but the most profitable age at which to slaughter is between eight and twelve months.

It is easiest to hold cows and pigs entirely without feed for eighteen or twenty-four hours prior to slaughtering, but they should have all the fresh water they will drink. This treatment promotes the elimination of the usual waste products from the system; it also helps to clear the stomach and intestines of their contents, which in turn facilitates the dressing of the carcass and the clean handling and separation of the viscera. No animal should be whipped or excited prior to slaughter.

For cutting up the meat, these old-fashioned tools still get the job done: A straight sticking knife, a cutting knife, a 14-inch steel, a hog hook, a bell-shaped stick scraper, a gambrel, and a meat saw (Figure 1 on previous page). More than one of each of these tools may be necessary if many hogs are to be slaughtered and handled to best advantage. A barrel is a convenient receptacle in which to scald a hog. The barrel should be placed at an angle of about 45 degrees at the end of a table or platform of proper height. The table and barrel should be fastened securely to protect the workmen. A block and tackle will reduce labor. All the tools and appliances should be in readiness before beginning.

A .22 caliber gun is best for killing cows and pigs. Male animals should be castrated before slaughtering. If you kill a pig in its pen, immediately afterward throw a noose around its neck and drag it outside to slit the throat while the heart is still beating. Cows should be slaughtered outside if they’re too large to drag. To sever the main veins and arteries, stick a knife into the throat and cut outward, through the skin. If slaughtering a pig, wash it down at this point.

Use a meat saw to remove the animal’s head. Cut slits in the Achilles tendons and insert the gambrel to hoist the animal up to a convenient height, using a pulley or a come-along as needed. The animal should be hanging upside down. Remove the feet at the joint.

Using a sharp, short knife, cut into the slit in the Achilles tendons and down the legs, stopping at the center line. Slice from the center line down to the animal’s neck. Begin to remove the skin, starting where the leg meets the center line and working outward. Leave as much fat intact as possible. Continue slicing around to the front of the leg, working toward the tailbone. Pull the tail sharply to separate the vertebrae.

Cut out the anus in order to remove the intestines. Cut down through the sternum through the belly, and finally between the legs. Be careful not to rupture the bladder. Place a bucket under the animal to catch all the innards. To remove the diaphragm and the heart, you’ll need to sever in from the surrounding connective tissue. Finally, remove the windpipe from the neck.

Pork should hang one night in a cold or refrigerated area. Beef can benefit from longer refrigerated aging.

Pigs should be halved before the meat is divided into portions. Cows should be quartered.

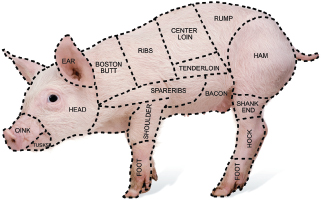

Cut off the front foot about 1 inch below the knee. The shoulder cut is made through the third rib at the breastbone and across the fourth. Remove the ribs from the shoulders, also the backbone which is attached. Cut close to the ribs in removing them so as to leave as much meat on the shoulder as possible. These are shoulder or neck ribs and make an excellent dish when fried or baked. If only a small quantity of cured meat is desired, the top of the shoulder may be cut off about one-third the distance from the top and parallel to it. The fat of the shoulder top may be used for lard and the lean meat for steak or roasts. It should be trimmed smoothly. In case the shoulders are very large, divide them crosswise into two parts. This enables the cure mixture to penetrate more easily and therefore lessens the danger of souring. The fat trimmings should be used for lard and the lean trimmings for sausages.

The ham is removed from the middling by cutting just at the rise in the backbone and at a right angle to the shank. The loin and fatback are cut off in one piece, parallel with the back just below the tenderloin muscle on the rear part of the middling. Remove the fat on the top of the loin, but do not cut into the loin meat. The lean meat is excellent for canning or it may be used for chops or roasts and the fatback for lard. The remainder should then be trimmed for middling or bacon. Remove the ribs cutting as close to them as possible. If it is a very large side, it may be cut into two pieces. Trim all sides and edges as smoothly as possible.

Cut off the foot 1 inch below the hock joint. All rough and hanging pieces of meat should be trimmed from the ham. It should then be trimmed smoothly, exposing as little lean meat as possible, because the curing hardens it. All lean trimmings should be saved for sausage and fat trimmings for lard. The other half of the carcass should be cut up in similar manner.

Separate the loin from the belly by sawing through the ribs, starting at the point of greatest curvature of the fourth rib. Skin the fat from the loin, leaving the lean muscle barely covered with the fat. The loins can be boned out and used for sausage if a large amount of that is desired, or if the weather will not permit holding them as fresh meat, they can be given a middle cure as boneless loins. The loin is best adapted for the pork (loin) roast or for pork chops. The latter are cut in such a way as to have the rib end in each alternate piece or chop.

Bacon comes from the pork belly.

After the carcass has been cut up and the pieces are trimmed and shaped properly for the curing process, there are many pieces of lean meat, fat meat, and fat which can be used for making sausage and lard. The fat should be separated from the lean and used for lard. The meat should be cut into convenient-sized pieces to pass through the grinder.

The leaf fat makes lard of the best quality. The back strip of the side also makes good lard, as do the trimmings of the ham, shoulder, and neck. Intestinal or gut fat makes an inferior grade and is best rendered by itself. This should be thoroughly washed and left in cold water for several hours before rendering, thus partially eliminating the offensive odor. Leaf fat, back strips, and fat trimmings may be rendered together. If the gut is included, the lard takes on a very offensive odor.

First, remove all skin and lean meat from the fat trimmings. To do this, cut the fat into strips about 1½ inches wide, then place the strip on the table, skin down, and cut the fat from the skin. When a piece of skin large enough to grasp is freed from the fat, take it in the left hand and, with the knife held in the right hand inserted between the fat and skin, pull the skin. If the knife is slanted downward slightly, this will easily remove the fat from the skin. The strips of fat should then be cut into pieces 1 or 1½ inches square, making them about equal in size so that they will dry out evenly.

Pour into the kettle about a quart of water, then fill it nearly full with fat cuttings. The fat will then heat and bring out the grease without burning. Render the lard over a moderate fire. At the beginning, the temperature should be about 160°F, and it should be increased to 240°F. When the cracklings begin to brown, reduce the temperature to 200°F or a little more, but not to exceed 212°F in order to prevent scorching. Frequent stirring is necessary to prevent burning. When the cracklings are thoroughly browned, and light enough to float, the kettle should be removed from the fire. Press the lard from the cracklings. When the lard is removed from the fire, allow it to cool a little. Strain it through a muslin cloth into the containers. To aid cooling, stir it, which also tends to whiten it and make it smooth.

Lard which is to be kept for a considerable amount of time should be placed in air-tight containers and stored in the cellar or other convenient place away from the light, in order to avoid rancidity. Fruit jars make excellent containers for lard, because they can be completely sealed. Glazed earthenware containers, such as crocks and jars, may be also be used. All containers should be sterilized before filling, and if covers are placed on the crocks or jars, they also should be sterilized before use. Lard stored in air-tight containers away from the light has been found to keep in perfect condition for a number of years.

A slab of pork lard

A slab of pork lard

When removing lard from a container for use, take it off evenly from the surface exposed. Do not dig down into the lard and take out a scoopful, as that leaves a thin coating around the sides of the container, which will become rancid very quickly through the action of the air.

SELECTING QUALITY MEAT

As a general rule, the best meat is that which is moderately fat. Lean meat tends to be tough and tasteless. Very fat meat may be good, but is not economical. The butcher should be asked to cut off the superfluous suet before weighing it.

1. Beef. The flesh should feel tender, have a fine grain, and a clear red color. The fat should be moderate in quantity, and lie in streaks through the lean. Its color should be white or very light yellow. Ox beef is the best, heifer very good if well fed, cow and bull, decidedly inferior.

2. Mutton. The flesh, like that of beef, should be a good red color, perhaps a shade darker. It should be fine-grained, and well-mixed with fat, which ought to be pure white and firm. The mutton of the black-faced breed of sheep is the best, and may be known by the shortness of the shank; the best age is about five years, though it is seldom to be had so old. Whether mutton is superior to either ram or ewe, it may be distinguished by having a prominent lump of fat on the broadest part of the inside of the leg. The flesh of the ram has a very dark color and is of a coarse texture; that of the ewe is pale, and the fat yellow and spongy.

3. Veal. Its color should be white, with a tinge of pink; it ought to be rather fat, and feel firm to the touch. The flesh should have a fine delicate texture. The leg-bone should be small; the kidney small and well-covered with fat. The proper age is about two or three months; when killed too young, it is soft, flabby, and dark-colored. The bull-calf makes the best veal, though the cow-calf is preferred for many dishes on account of the udder.

4. Lamb. This should be light-colored and fat, and have a delicate appearance. The kidneys should be small and imbedded in fat, the quarters short and thick, and the knuckle stiff. When fresh, the vein in the fore quarter will have a bluish tint. If the vein looks green or yellow, it is a certain sign of staleness, which may also be detected by smelling the kidneys.

5. Pork. Both the flesh and the fat must be white, firm, smooth, and dry. When young and fresh, the lean ought to break when pinched with the fingers, and the skin, which should be thin, yield to the nails. The breed having short legs, thick neck, and small head is the best. Six months is the right age for killing, when the leg should not weigh more than 6 or 7 lbs.

The first essential in curing pork is to make sure that the carcass is thoroughly cooled, but meat should never be allowed to freeze either before or during the period of curing.

The proper time to begin curing is when the meat is cool and still fresh, or about twenty-four to thirty-six hours after killing. See page 65 for pork curing suggestions.