Your Weight Is Not Your Fault

How “the obesogen effect” is messing with your metabolism—and how stripping chemicals from your diet will help you start dropping pounds

Decades ago, before big, soft guts were the American norm, we often referred to overweight people as having “glandular problems.” Their weight was not their fault, doctors explained; their bodies just didn’t have the ability to fight off weight gain like most people’s did.

We don’t use that polite phrase any longer. What changed? Now that one in three American adults is overweight or obese, did those folks with “glandular problems” just disappear? No, not at all. It’s just that the rest of us have caught the same disease. Thanks to the obesogen effect brought on by America’s food manufacturers and other consumer product marketers, right now we’re all at risk for some serious glandular problems.

It’s true that becoming overweight has a lot to do with the amount of calories you consume in relation to the amount that you burn, especially in regard to your resting metabolism. And your genes can predispose you for weight gain, making it harder to keep off pounds if your parents were hefty. But that’s only two-thirds of the story. There’s another class of culprits lurking in your fatty tissues, and they’re entering your body via foods, beverages, and other products. They’re called obesogens—also known as endocrine disruptors or “environmental estrogens”—and what they cause is, well, glandular problems.

Obesogens are a group of manmade and naturally occurring chemicals that can be found hiding in our food, our water, our plastics, and our cosmetics and fragrances. And we drink them, eat them, breathe them, and absorb them through our skin every single day. “There is a lot of exposure,” says Jerry Heindel, Ph.D., an expert on endocrine disruptors with the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. These chemicals also have an insidious, poisoning effect on the environment. Reduce your exposure to them, and you’ll strip away pounds in ways you’ve never seen before.

The Chemistry of Weight Gain

Because high school biology was probably a while back, here’s a quick refresher: The endocrine system is made up of all the glands and cells that produce the hormones that regulate our bodies. Growth and development, sexual function, reproductive processes, mood, sleep, hunger, stress, metabolism, and the way our bodies use food—it’s all controlled by hormones. And the pancreas, prostate, lymph nodes, thyroid, pituitary gland, ovaries/testes, and breast tissue are all part of that system. So whether you’re a boy or a girl, tall or short, hirsute or hairless, lean or heavy, whether you have even or uneven monthly cycles—that’s all determined in a big way by your endocrine system.

But your endocrine system is a finely tuned instrument, and it can easily be thrown off its game. That’s why these chemicals are so good at making us fat.

Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) mimic natural hormones. According to researchers at Tulane University’s Center for Bioenvironmental Research, EDCs can fool the body into overresponding to hormones, or cause it to respond at inappropriate times. EDCs can block the effects of hormones altogether, and even directly stimulate or inhibit the endocrine system, causing the overproduction or underproduction of essential hormones. This is essentially how birth-control pills work, by the way: They disrupt a woman’s hormonal system, confusing her body and causing her not to ovulate. So used sparingly, and for specific purposes, EDCs can make medical sense.

Problem is, our bodies are now being bombarded by EDCs all the time, and not under the supervision of a doctor.

In the past few years, dozens of studies have come out linking EDCs to weight gain and other diseases. And in a recent statement, the Endocrine Society, the largest organization of experts devoted to research on hormones and the clinical practice of endocrinology, reported that “accumulating data are pointing to the potential role of endocrine disruptors either directly or indirectly in the pathogenesis of adipogenesis [weight gain] and diabetes, the major epidemics of the modern world.” In other words, evidence indicates that EDCs might be among the root causes of the major diseases of our time: cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and obesity.

“We refer to these chemicals as obesogens—chemicals related to increased body weight,” says Frederick vom Saal, Ph.D., curators’ professor of biological sciences at the University of Missouri and one of the first researchers to raise the alarm about endocrine disrupting chemicals. “Obesogens are thought to act by hijacking the regulatory systems that control body-weight homeostasis,” says Dr. vom Saal, “and any chemical that interferes with body weight is an endocrine disruptor.”

For example, leptin, a hormone produced by fat cells, has gotten the attention of many researchers lately because it helps us eat less by triggering the feeling of being “full.” But early exposure to the obesogen bisphenol A (BPA), a component found in hard plastic bottles and the linings of some canned goods, can cause abnormal surges in leptin that, according to Harvard University researchers, alter leptin programming in the body in a way that leads to obesity.

That’s double jeopardy for a lot of us, because fructose (including high-fructose corn syrup, the artificial sugar that’s in almost every can of soda and thousands of other items on supermarket shelves and restaurant menus) can disrupt the way leptin works in the body even further, says Robert Lustig, M.D., an endocrinologist at the University of California at San Francisco. In some people with weight issues, fructose interferes with the body’s satiation sensors, so essentially they’re always hungry, even when they’re full.

And researchers are just beginning to understand how these chemicals interact within our bodies in even more disturbing ways.

What This Means to Your Body

Endocrine disruptors have been linked to infertility, genital malformation, reduced male birth rates, precocious puberty, miscarriage, behavior problems, brain abnormalities, impaired immune function, various cancers, and heart disease. “Basically, we have data linking environmental chemicals to practically every major human disease, from cardiovascular disease to attention deficit disorder,” says Dr. Heindel.

A 2008 study in the Journal of Andrology noted that more and more young men have low sperm counts, and more and more boys are born with malformed sexual organs; the researchers believe exposure to EDCs is to blame. And in the United States and Japan, fewer boys are being born, according to a 2007 study in the Journal of the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. The study authors suggest that exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals—by women during pregnancy, and by men before they conceive children—may be to blame.

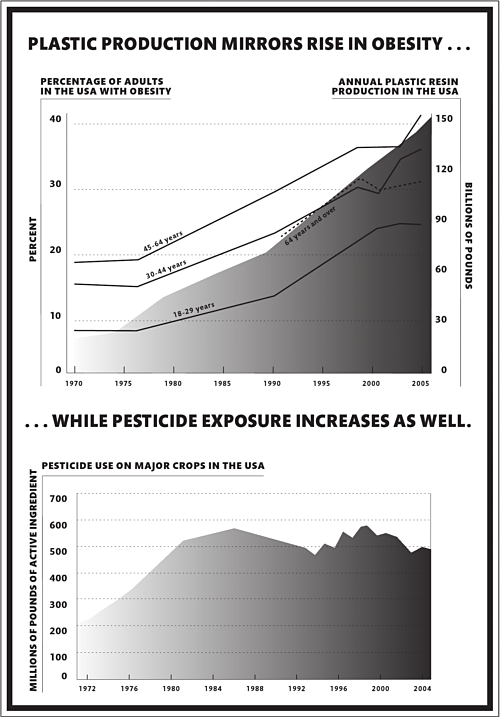

And now, a flood of new research is finding that some endocrine disruptors, the obesogens, are making us fat. Obesogens include chemicals in plastics (BPA, phthalates, PCBs, PFOA, and organotins—specifically diorganotins, the heat stabilizers used in PVC); fungicides and pesticides used on citrus fruits, vegetables, cotton, and hops (azocyclotin, fenbutatin oxide, tributyltin oxide, and triphenyltin acetate), and even high levels of natural chemicals such as lead and cadmium. Some of these chemicals have recently been linked to diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and obesity. Consider:

* The first major epidemiologic study that examined the health effects of BPA was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in September 2008, and it linked BPA exposure with common diseases such as heart disease and type 2 diabetes, and liver enzyme abnormalities.

* A recent study in Diabetes Care found that people with higher levels of six EDCs, including dioxins and PCBs, had a higher risk of diabetes, regardless of whether they were overweight. Compared with people with the lowest levels, those with the highest combined levels of EDCs had a 38-fold greater risk of having diabetes.

* Researchers reporting in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives showed that regular exposure to BPA, which leaches into your body from canned foods and beverages, suppresses the release of the hormone adiponectin. Adiponectin increases insulin sensitivity and reduces tissue inflammation, so suppressing it could lead to insulin resistance and increased susceptibility to metabolic syndrome and obesity.

* Canadian researchers report that dieters with the most organochlorines (pollutants from pesticides sprayed on corn, soy, and other high-value crops) stored in their fat cells are the most susceptible to disruptions in mitochondrial activity and thyroid function, causing a greater-than-normal dip in metabolism. In other words, pesticides make it harder to lose weight and easier to pack on pounds.

* A study in the journal BioScience found that tributyltin (a chemical used in pesticides on many crops, including lettuce, tomatoes, and soybeans) activates components in our cells known as retinoid X receptors, which switch on genes that cause the growth of fat-storage cells. The study authors found that tributyltin causes the growth of excess fatty tissue in newborn mice exposed to it in utero. Since the rise in obesity in humans over the past 40 years parallels the increased use of industrial chemicals, the researchers suggest chemical triggers might be fueling the obesity epidemic.

* A recent study in Molecular Endocrinology found that EDCs not only create more fat cells, they also enlarge them and make them better at storing fat.

And these are just a few of the studies that have come out in the past two years implicating EDCs with obesity and other metabolic disorders.

More troubling still: Studies suggest that exposure to these chemicals in utero and during early development is the most dangerous. Children are five times more susceptible to EDCs because they have lower levels of an essential enzyme that helps the body eliminate toxins. And more and more studies are finding that although early exposure to EDCs may not cause immediate problems, there is a latent period before disease or dysfunction becomes obvious. In other words, early exposure to EDCs sets children up for a host of metabolic problems, including obesity.

And the latest research suggests that obesogens cause problems across generations and at very, very low doses.

Researchers are reporting new data, both in animals and in humans, that indicate the effects of these chemicals can be seen not just in our bodies, but across three or four generations. So a pregnant woman’s exposure affects her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. “These chemicals are changing us in ways that people did not understand 30 to 40 years ago,” says Dr. vom Saal. All the measures we’ve used in the past to determine if these chemicals are safe don’t apply anymore, he says.

The obesogen effect happens at a genetic level, but we’re not altering our genes, per se. Instead, we’re altering the way they behave. These are known as “epigenetic mechanisms.”

Epigenetics means “on top of genetics.” Everybody has 30,000 genes in their DNA, and those genes are turned on and off during development so the body can make different tissues—for the heart, the liver, the kidneys, and so on. “What controls all that is this whole new system we’ve discovered, called the epigenetic system,” says Dr. Heindel. Epigenetics basically controls whether a gene can be turned on or off . “And a lot of that is controlled by hormones,” explains Dr. Heindel. So if you get a disturbance in the amount of hormone, say from exposure to an obesogen, genes can be turned on or off at the wrong time, which changes the gene in a way; it functionally looks normal, but at a molecular level, it just isn’t behaving right. “With these mutations, it’s like you take a word and put a French accent on it,” says Dr. vom Saal. “And with that accent on it, the word means something different.

“Perhaps what’s most scary is that these chemicals are harmful in the part-per-trillion range,” Dr. vom Saal continues. “We find that obesogens like BPA can actually stimulate cells below a part per trillion. Below, not at.”

Now remember all the different sources of obesogens: plastic piping and weed killer in our drinking water, plastic resin in our food containers, natural EDCs from soy products. Tiny doses, but they add up to quite a cocktail. There’s even a new field of study that scientists are calling “something from nothing,” which says that low-level exposure to many different chemicals has an exponentially huge effect. “Let’s say you’re exposed to 10 different obesogens at a low dose. Individually they might not do much, but combined you get a huge effect. They add up,” says Dr. Heindel. “We’re basically changing the whole face of what humans look like.”

Uncovering the Hidden Flab-Builders

If you, the average American, were to take a blood sample to a lab right now, they would find, on average, 280 industrial chemicals floating around your system, and some of them would be obesogens. Some are naturally occurring, like the phytoestrogen genistein that’s found in soy products. But others are produced for use in pesticides, plastics, cosmetics, electrical transformers, and a host of other products. Here is where you’ll find many of the common culprits:

IN YOUR FRIDGE : Pesticides and PCBs

The average person is exposed to 10 to 13 pesticides each day via fresh fruits, vegetables, milk, and juice, according to the USDA’s Pesticide Data Program. More than half of the most widely used pesticides on the market today are known endocrine disruptors, including nine of the 10 pesticides we come in contact with the most through food, according to a recent study by the Organic Center, a nonprofit organization devoted to advancing peer-reviewed scientific research on organic food and farming. Some pesticide EDCs include DDT, DDE (a breakdown product of DDT that is found in corn, soy, and milk), atrazine (one of the most widely used weed killers, sprayed on corn and soy fields and found in our water), vinclozolin (fungicide), tributyltin (used in antifouling paints for ship hulls, it accumulates in fish), carbendazim (fungicide), HPTE (a widely used insecticide), and endosulfan (found in milk). Plus, PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls)—chemicals that were widely used in the past in industry as lubricants, coatings, and insulation materials, as well as in fluorescent lights, various appliances, and televisions —tend to be stored in fatty tissue. Even though they were banned by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1979, they still show up today in milk (breast and dairy), meat, and fish.

IN YOUR PANTRY: Plastic compounds

Detectable in 75 percent of Americans, phthalates are plastic softeners that mimic estrogen. They’re found in the lining of canned foods and beverages, sports drink bottles, and pesticides, as well as children’s toys, PVC pipes, auto parts, and medical supplies. We create about 1 billion pounds of phthalates a year worldwide, and they leach easily into our blood, urine, saliva, seminal fluid, breast milk, and amniotic fluid. We produce 6 billion pounds of the obesogen BPA every year, and it’s detectable in 93 percent of Americans. BPA leaching occurs from food and drink packaging, baby bottles, cans, and bottle tops. A recent study by the Environmental Working Group found that one in 10 cans of all food tested, and one in three cans of infant formula, contained BPA levels more than 200 times the government’s traditional safe level of exposure for industrial chemicals. Canned chicken soup, infant formula, and ravioli had BPA levels of the highest concern, with beans and tuna close behind.

IN YOUR WATER : Hormones, pesticides, and other industrial chemicals

According to the USDA’s Pesticide Data Program, 54 percent of tap water tests positive for pesticides. A new study by the Natural Resources Defense Council found that the pesticide atrazine was detected in municipal water supplies 90 percent of the time. Every watershed tested had traces of the pesticide, 22 percent had levels higher than 50 parts per billion (ppb), and 10 percent had levels exceeding 100 ppb (the EPA set safe levels of atrazine in drinking water at 3 ppb). According to the American Chemical Society, pharmaceuticals (including birth-control hormones, cholesterol drugs, epilepsy drugs, and antidepressants) and personal-care products such as fragrances and soaps are found in most rivers and show up even in treated water. Ethynylestradiol, the main synthetic estrogen in birth control, makes its way into waterways, contaminating water sources and leaching into fish. Alkylphenols, chemicals used in a variety of consumer goods such as liquid clothing detergents and some pesticides, make their way into drinking water as well.

But there is hope…

How the New American Diet Can Protect You and Your Family

As we said in the last chapter, there are plenty of diet plans out there that offer plenty of advice on how to lose weight, based on traditional food science. But traditional food science doesn’t take into account the array of chemicals now being used in or around our food, and how those chemicals alter the way the human body reacts to those foods. An apple a day could keep the doctor away, back 250 years ago when Ben Franklin first coined the phrase. But Franklin and the other Founding Fathers never had to worry about what industrial farmers were spraying on the local orchards. (Consider this: The New York Times reported recently on residents in a housing development in New Jersey who have been embroiled in a lawsuit for years with the developers who built their neighborhood on an old peach and apple orchard. The orchard closed in the 1970s, but the land still has pesticide concentrations that exceed state safety standards, and the kids aren’t allowed to play in their own backyards. In other words, these chemicals linger.)

The New American Diet, on the other hand, takes the latest science on weight loss to heart. It is designed to strip away flab, not only by boosting your intake of nutrients, but also by reducing your exposure to pollutants that undermine your dieting attempts and increase your risk of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and more. Here are some of the most important steps you can take today to protect yourself and start losing those extra pounds.

Know when to eat organic

According to a recent study in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, eating an organic diet for just 5 days can reduce circulating pesticide obesogens to indetectable or near indetectable levels. Other recent studies by researchers at Harvard University School of Public Health have confirmed that an organic diet can seriously decrease the amount of circulating obesogens in the body. Of course, organic foods can be expensive. But not all organics are created equal; many foods have such low levels of pesticides that buying organic just isn’t worth it. The Environmental Working Group calculated that you can reduce your pesticide exposure by nearly 80 percent simply by choosing organic for the 12 fruits and vegetables shown in their tests to contain the highest levels of pesticides. They call them “The Dirty Dozen,” and (starting with the worst) they are peaches, apples, sweet bell peppers, celery, nectarines, strawberries, cherries, kale, lettuce, imported grapes, carrots, and pears. On the other side, you can feel good about buying the following 15 conventionally grown fruits and vegetables that the EWG dubbed “The Clean Fifteen,” because they were shown to have little pesticide residue: onions, avocados, sweet corn, pineapples, mangoes, asparagus, sweet peas, kiwis, cabbages, eggplants, papayas, watermelons, broccoli, tomatoes, and sweet potatoes. Also, by choosing hormone-free meats and dairy, you’ll avoid exposure to the many anabolic and estrogenic hormones—three of which are naturally occurring (estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone) and three of which are synthetic (the estrogen compound zeranol, the androgen trenbolone acetate, and progestin melengestrol acetate)—that have been used for decades to promote the fattening and growth of farm animals (more on that in Chapter 3).

DIY PESTICIDE-PROOFING PRODUCE WASH

Chronic exposure to pesticides—from, say, eating fruits and vegetables without washing them—can result in everything from dizziness and headaches to cancer and obesity. Buying organic will help reduce your exposure, but even organic produce can harbor salmonella and E. coli, as well as trace levels of pesticides, so it’s critical that you clean all fruits and vegetables prior to eating them. If you’re in a rush, rinsing them for 20 seconds under cold tap water will get rid of most dirt and pesticides, and do a decent job with bacteria. The best option, however, is to make your own produce wash. Combine 1 tablespoon of lemon juice, 2 tablespoons of distilled white vinegar, and 1 cup of cold tap water in a spray bottle, shake well, and then apply to your produce. Rinse with tap water and serve. Lemon juice is a natural disinfectant, and the white vinegar will neutralize most pesticides. Whatever you do, however, don’t “clean” an apple (or any other fruit) by rubbing it on your shirt. All that does is move the pesticides and bacteria around a bit.

Chronic exposure to pesticides—from, say, eating fruits and vegetables without washing them—can result in everything from dizziness and headaches to cancer and obesity. Buying organic will help reduce your exposure, but even organic produce can harbor salmonella and E. coli, as well as trace levels of pesticides, so it’s critical that you clean all fruits and vegetables prior to eating them. If you’re in a rush, rinsing them for 20 seconds under cold tap water will get rid of most dirt and pesticides, and do a decent job with bacteria. The best option, however, is to make your own produce wash. Combine 1 tablespoon of lemon juice, 2 tablespoons of distilled white vinegar, and 1 cup of cold tap water in a spray bottle, shake well, and then apply to your produce. Rinse with tap water and serve. Lemon juice is a natural disinfectant, and the white vinegar will neutralize most pesticides. Whatever you do, however, don’t “clean” an apple (or any other fruit) by rubbing it on your shirt. All that does is move the pesticides and bacteria around a bit.

Use safe plastics

Levels of BPA in the body increase by nearly 70 percent after people drink out of polycarbonate (#7) plastic bottles for just 1 week, according to researchers from Harvard University and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (See “Plastic by the Numbers” on page 58 for more information on which plastics to avoid.) Never use plastic containers to heat food and never put them in the dishwasher, which can damage them and increase leaching. Dr. vom Saal says that for his family’s protection, he has instituted a few rules: “We’re really careful about packaging. No plastic item ever goes into the oven or the microwave.” He also suggests avoiding fatty foods like meats that are packaged in plastic wrap. “The plastic wrap used at the supermarket is mostly PVC, whereas the plastic wrap you buy to wrap things at home is increasingly made from polyethylene. PVC is such a nightmare; it contains phthalates that lower testosterone levels.” Lower testosterone leads to a decrease in muscle mass and sex drive, and an increase in weight.

Kick the can

BPA leaches into food from the internal epoxy resin coatings of canned foods. And one out of five canned foods (and one out of three canned vegetables and pastas such as ravioli and noodles with tomato sauce) contains levels of BPA that exceed the levels deemed safe by the EPA, according to a recent study by the Environmental Working Group. (And remember, what the EPA deems safe are far, far higher concentrations than what current obesogen researchers agree with.) Along with pastas and vegetables, they found unsafe levels of BPA in canned soda, tuna, peaches, pineapples, infant formulas, and tomato and chicken noodle soups. Acidic foods are among the worst (tomatoes, citrus, acidic sodas, and beer) because they increase the rate of leaching. This is one reason why Japan banned the use of BPA in canned goods way back in 1999—and that was before scientists had even discovered the obesogen effect!

Unfortunately, jarred foods aren’t much better, thanks to the plastic lining in their lids. A recent study by Health Canada tested glass-jarred baby food and found BPA in 84 percent of the samples. What to do? Buy frozen vegetables in bags, soda in plastic bottles, and beer in glass bottles, and get your canned and jarred foods from Eden Organic, the only company that doesn’t have BPA in its cans.

Filter your water

The best way to eliminate EDCs from your tap water is to use an activated carbon water filter. Available for faucets and pitchers, and as under-the-sink units, these filters remove most pesticides and industrial pollutants. Check the label to make sure the filter meets the NSF/American National Standards Institute’s standard 53, indicating that it treats water for both health and aesthetic concerns. Try the Brita Aqualux ($28, brita.com), Pur Horizontal faucet filter ($49, purwaterfilter.com), or Kenmore’s under-the-sink system ($48, kenmore.com).

Go lean

Most endocrine disruptors are fat soluble, so they accumulate in fatty tissue, which means the greatest exposure comes from eating fatty foods and fish from contaminated water. Always choose pasture-raised meats, which studies show have less fat than their confined, grain-fed counterparts. Choose lean cuts of beef such as top sirloin, 95 percent lean ground beef, bottom round roast, eye round roast, top round roast, and sirloin tip steak. Bison burgers and veggie burgers are also great substitutes when grass-fed beef isn’t available. And select sustainable fish with low toxic loads, such as farmed rainbow trout, farmed mussels, anchovies, scallops (bay or farmed), Pacific cod, Pacific halibut, white meat or albacore tuna (in a pouch container, not in a can), and mahimahi.

Use Pyrex, not plastic

BPA leaches from polycarbonate sports bottles 55 times faster when exposed to boiling liquids as opposed to cold ones, according to a study in the journal Toxicology Letters. Avoid heating food in plastic containers or storing fatty foods in plastic containers or plastic wrap. While some plastics are considered “safe,” a recent Health Canada study found high levels of BPA in plastics marketed as BPA-free. They’re not sure how the chemical got in there and suggest it might be due to cross-contamination of plastics during manufacturing. Until there are tighter regulations on this ubiquitous chemical, do your best to avoid plastic wherever you can. And at the very least, keep hot beverages and foods out of plastic containers—paper cups, not Styrofoam, for your morning coffee.

Plastic by the Numbers

Plastic by the Numbers

What does the U.S. government say about bisphenol A (BPA)—the ubiquitous chemical found in hard plastic bottles, canned and jarred foods, and baby bottles? Well, the Food and Drug Administration’s policy, up until 2009, has been that BPA is safe at current levels. But scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Environmental Protection Agency, as well as researchers at three major universities, report that BPA is not safe. That’s disquieting news for the 93 percent of Americans who already test positive for the chemical. Congress moved in 2009 to ban BPA in baby bottles, and has pressured the FDA to review its stance. The results of the FDA’s review were due as this book went to press. In the meantime, there’s enough evidence to suggest that limiting your intake of canned foods and learning what the numbers on plastic packages really mean are critical steps you should take to reduce your exposure.

#1 | PETE

(polyethylene terephthalate ethylene)

Found in: Soda, juice, and water bottles, as well as some containers for peanut butter and salad dressing.

Health risks: This plastic is not known to leach any dangerous chemicals.

Tip: Use once and then recycle.

#2 | HDPE

(high-density polyethylene)

Found in: Opaque water and milk bottles, yogurt and butter containers, and soft plastic sports bottles.

Health risks: Same deal as PETE: generally safe.

Tip: Use once and discard.

#3 | PVC

(polyvinyl chloride)

Found in: Some plastic wraps, squeeze bottles, and peanut-butter containers, as well as vinyl flooring, shower curtains, and car interiors. Health risks: The most toxic of all plastics. Leaches phthalates, a probable human carcinogen and endocrine disruptor, which can migrate into fatty foods, such as deli meats and cheeses.

Tip: Avoid at all costs. Instead, use waxed paper and buy meat wrapped in paper from the butcher. If you use plastic-wrapped cuts, trim the edges off where the product came in contact with plastic. Use natural materials for home flooring. Buy a shower curtain made from hemp, which lasts longer and is naturally mildew-resistant. New vinyl emits toxins into the air at the highest concentrations, so open windows to air out spaces featuring brand-new vinyl materials.

#4 | LDPE

(low-density polyethylene)

Found in: Grocery-store bags, plastic wrap, sandwich bags, and many squeeze bottles.

Health risks: Generally safe.

Tip: Use once and discard.

#5 | PP

(polypropylene)

Found in: Cloudy plastic baby bottles, sippy cups, some food-storage containers, and many takeout containers.

Health risks: Generally safe.

Tip: Treat like #2 (HDPE) plastics.

#6 | PS

(polystyrene)

Found in: Styrofoam food containers and clear plastic containers and cups.

Health risks: Can leach styrene, a possible carcinogen and known neurotoxin that can cause depression and loss of concentration; has been linked to cancer.

Tip: Avoid at all costs. Choose paper cups (without a wax lining) whenever possible, and drink from a reusable ceramic coffee mug at work. If your takeout comes in polystyrene, transfer the food to ceramic or glass as soon as you get home.

#7 | Other

(usually polycarbonate)

Found in: Hard plastic water and baby bottles, canned foods, sippy cups, and stain-resistant food-storage containers.

Health risks: Leaches BPA, increasing the risk of heart disease, diabetes, decreased testosterone, enlarged prostate, low sperm count, impaired immune function, and obesity.

Tip: Avoid at all costs. Upgrade to BPA-free “Everyday” water bottles ($11.50, nalgene-outdoor.com) and Klean Kanteen sippy cups ($18, kleankanteen.com). Plastic releases toxins over time when damaged or if exposed to high heat. “Plus, foods high in fat and acid increase leaching from these plastics,” says Kathleen Schuler of the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy.

One More Head’s Up:

Beware of containers with a waxy lining, and nonstick pans.

Health risks: Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), a grease-repelling fluorotelomer chemical and likely human carcinogen, can migrate from the waxy plastic coating onto the food inside, especially at high temperatures. It has been linked to cancer, plus lung and kidney damage.

Tip: At home, avoid Teflon-coated pans. If you can’t live without them, never use metal utensils, which can scratch the Teflon and turn it into an ingredient in your food. Your best bet is to replace those pans with nontoxic cookware made from stainless steel, copper, or cast iron.