The New American Baby

Why our children’s bodies are under assault, and how to protect them from obesity and more

Of all the scary things to worry about when you’re expecting a child—Down syndrome (about one in every 800 live births), stillbirths (one in every 160 pregnancies), miscarriage (one in every five to 10 pregnancies)—there’s one health problem that’s still not on most people’s radar, even though it affects almost every baby born today: exposure to obesogens.

America’s children are growing up in a world where scientists predict that 100 percent of them will be overweight or obese as adults. Obesity rates among infants have increased 73 percent in the past quarter century, and one in three children born this decade will become diabetic. And simple principles—eat less fat, choose chicken or salmon over beef, eat plenty of vegetables—aren’t going to help them. Many factors are altering the way our bodies interact with food, from the hidden calories in many processed products to the way our meat and produce is being grown and prepared. But America’s obesity epidemic has a more insidious under lying cause thatfew of us consider in making our nutritional choices: We’re eating and drinking too many obesogens, or endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs). In fact, in a recent statement by The Endocrine Society, the largest organization of experts devoted to research on hormones and the clinical practice of endocrinology, researchers noted that the rise in the incidence of obesity matches the rise in the use and distribution of endocrine disrupting chemicals, and concluded that EDCs play a major role in the obesity epidemic and other modern illnesses.

While obesogens can trigger health effects throughout our lifetime, our bodies are most sensitive to them in our first weeks and months in the womb, when our cells are first dividing and deciding what we will become. “During the time of differentiating of the cells, endocrine disrupting chemicals disrupt normal epigenetic determination processes that in adulthood lead to cellular breakdown and cancers and all kinds of things. That’s absolutely certain,” says Frederick vom Saal, Ph.D., curators’ professor of biological sciences at the University of Missouri and one of the first researchers to raise the alarm about endocrine disrupting chemicals. “There’s a huge amount of literature on this.” “Epigenetics” means “on top of genetics,” and it refers to the manner in which our genes behave.

And because EDCs tamper with our genes, the damage doesn’t necessarily stop with you, or even with your child. Some scientists are raising serious concerns about what they call “transgenerational effects”—essentially, we’re altering how our genes behave, so that we not only become obese ourselves, but we pass our newfound obesity on to future generations. “If a mother is exposed and that causes some problems in the off spring, then those off spring, when they have children, (those children will) have problems also,” says obesogen expert Jerry Heindel, Ph.D., of the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. “So that’s really kind of scary….They are starting to get data in both animals and in humans that things can go three or four generations.”

Obesogens come to us from a host of sources, but as you’ve read in previous chapters, the majority of our exposure comes from pesticides used on produce, hormones fed to livestock, and chemicals that leach out of plastic food containers, water pipes, and consumer products. Protection of your child’s delicate endocrine system needs to begin in utero and during early childhood.

What Parents Need to Know

Before they are even born, American babies are exposed to hundreds of chemicals in the womb. Many of them fall into a class of toxins called obesogens. As you’ve already read, these chemicals have been shown to mimic naturally occurring hormones, particularly estrogen, and block the enzymes that synthesize hormones. Before birth, they can have the effect of disrupting the delicate balance of the endocrine system. And after a child is born, obesogens can act slowly over time to have the same effect.

According to researchers at Tulane University’s Center for Bioenvironmental Research and researchers at the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, obesogens can fool the body into overresponding to hormones, they can block the effects of hormones altogether, and they can even directly stimulate or inhibit the endocrine system, causing the overproduction or underproduction of essential hormones. Scientists have begun to raise more and more concerns about obesogens, linking them not only to weight problems, but to a wide variety of health issues, from a decrease in the number of boys being born, to lowered sperm counts, birth defects, infertility, autism, and even diabetes. “There’s data that sperm counts have been going down a little bit every year for the past 40 years or so,” says Dr. Heindel. “Plus, testosterone levels in men are going down, and there are some sex changes occurring. A lot of scary things are going on because of exposure to endocrine disruptors.”

The Special Risk to Children

Children are five times more susceptible to some pesticide obesogens because they have lower levels of paraoxonase 1 (PON1), an essential enzyme that helps the body eliminate toxins, according to a recent study in Environmental Health Perspectives. The researchers found that children don’t develop their full levels of protection from toxins until age 7 (on average, the quantity of the enzyme quadruples between birth and age 7). And even though obesogens may not cause immediate problems, there appears to be a latent period before disease or dysfunction becomes apparent.

Bruce Blumberg, Ph.D., a developmental biologist at the University of California–Irvine, recently reported that when parents are exposed to the obesogen tributyltin (a chemical used in plastic water pipes and plastic food wrap, and as a fungicide on corn and soy), it can trigger a genetic switch in their offspring that predisposes the offspring to become fat as adults. Dr. Blumberg says that developmental exposure is much more serious than adult exposure because “the proobesity reprogramming is irreversible, which means you will spend your life fighting weight gain.” In other words, exposure to obesogens in the womb creates permanent genetic changes that set babies up for a lifetime of being overweight.

The idea that adult diseases might be traced back to the womb is not new (researchers have known for years that poor fetal nutrition is related to increased risk of heart disease and diabetes), but this concept, called the developmental origins of adult disease (or the fetal basis for disease), has only recently been applied to obesogen exposure. And the results are shocking.

One study from the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) states that “EDCs disrupt the programming of endocrine signaling pathways that are established during perinatal life and result in adverse consequences that may not be apparent until much later in life.” The researchers suggest that exposure to environmental

chemicals such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), DDE (the breakdown product of DDT), and other pesticides leads to obesity. The study authors report that “exposure to environmental chemicals during development may be contributing to the obesity epidemic.”

Another NIEHS study states that obesity and diabetes should be added to the growing list of adverse consequences that have been associated with developmental exposure to environmental estrogens.

And a study by Tufts University School of Medicine researchers found that female mice whose mothers were exposed to the obesogen bisphenol A (BPA) from early pregnancy showed increased weight in adulthood. (BPA is a chemical used to make hard plastic food containers and reusable water bottles, and is found in the lining of soft drink and food cans, as well as some children’s toys.) The study noted that EDCs led to decreased insulin sensitivity and a decrease in sensitivity to the weight-regulating hormone leptin. The study authors report that “developmental exposure to this chemical prior to and just after birth can exert a long-lasting influence on body-weight regulation.”

And these are just the recent studies linking obesogens to weight problems. There are a host of other studies linking prenatal and infant exposure to obesogens to neurological disorders. A study in the journal NeuroToxicology found that children born in homes that have PVC vinyl flooring (which contains phthalates, chemicals used to make plastic more flexible and that have an antiandrogenic effect) in their nurseries or parents’ bedrooms are twice as likely to be diagnosed with autism as those with wood or linoleum flooring. And a study in Environmental Health Perspectives found that autism rates are six times higher in children born of mothers who live close to fields sprayed with pesticides.

The problem is, information about obesogens is only now breaking into the medical mainstream, so following the traditional advice from your doctor on how to have a healthy

pregnancy isn’t enough to protect you or your baby. You need to make a few New American Diet tweaks to your eating habits and your lifestyle in order to reduce your family’s exposure to harmful obesogens.

Protecting Our Children’s Future

The full scope of the link between adult disease and obesogen exposure has yet to be entirely understood. A large-scale study tracking 100,000 children from before birth through age 21, called the National Children’s Study, kicked off in January 2009 to examine how maternal health, environmental exposures, and the fetal environment are associated with adult disease. Early results should start to be published in 2011, and from them we will be able to develop better preventive strategies and safety guidelines. Until then, we have to do what we can to limit exposure to obesogens and reduce the chemical load that our children are exposed to in the womb and as infants.

There are plenty of products in the typical U.S. household that we should begin to eye suspiciously. (See “Your Big Fat House” on page 265 for a room-by-room breakdown.) But according to the Natural Resources Defense Council, what you eat and drink are the most important factors in protecting your baby from chemicals. We scoured the scientific literature, found the best ways to reduce your child’s exposure to obesogens, and put together the New American Diet Baby Guidelines:

Eat organic when you can

Fat is essential for a newborn baby’s growth and development. But fat is also where obesogens tend to migrate and be stored. And breast milk’s high fat content makes it a magnet for obesogens. Dioxins, PCBs, PBDEs (flame retardants), and pesticides are just some of the toxins found in breast milk. But according to a study in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, eating an organic diet for just 5 days can reduce

circulating pesticide obesogens to indetectable or near indetectable levels. Always choose organic dairy and freerange organic meats and eggs (again, dairy and meat are loaded with fat, so they’re like flypaper for pesticides). Always go organic when you’re selecting the Dirty Dozen. Just opting for the organic version of these 12 foods can cut the amount of pesticides in your system by 80 percent!

Avoid big, fatty fish

A study in the journal Occupational and Environmental Medicine found that even though the pesticide DDT was banned in 1973, the chemical and its breakdown product DDE can still be found today in fatty fish. The researchers go on to report that higher prenatal exposure to DDE increases the risk of obesity in adult women. The team started studying a group of Lake Michigan fish eaters and their offspring in the early 1970s. They looked at 259 mothers in the group and their adult daughters, ages 20 to 50 in the year 2000. When compared with the adult daughters who had been exposed to the lowest levels of DDE in the womb, those exposed to intermediate levels were an average of 13 pounds more overweight, and those exposed to the highest levels were an average of more than 20 pounds overweight. Bigger fish eat smaller fish, so they carry a much higher toxic load.

Avoid: Alewife, Chilean sea bass, bass (wild striped), bluefish, croaker, eel, flounder, grouper, mackerel (king and Spanish), marlin, orange roughy, oysters (wild), rockfish, salmon (farmed), shad, shark, farmed shrimp, swordfish, wild sturgeon, tilapia, tilefish, tuna (bluefin)

Choose: Farmed rainbow trout, farmed mussels, anchovies, scallops (bay or farmed), Pacific cod, Pacific halibut, albacore tuna (in packets, not cans), mahimahi

Also, when you cook the fish, broil, poach, grill, boil, or bake instead of pan-frying to allow contaminants from the fatty portions of fish to drain out.

Choose the right formula

A study in the journal Circulation found that soy-based infant formula containing the naturally occurring obesogen genistein has also been associated with obesity later in life. “You do not want to put soy into a baby’s mouth,” says Dr. vom Saal. “Babies who are fed soy end up with enough phytoestrogen in their systems to disrupt the menstrual cycle of an adult woman. We are the only country that allows this. We’re the Wild West when it comes to the chemical treatment of our babies.”

Adding to our babies’ exposure is the fact that most food cans, including most cans that contain formula, have plastic linings that contain BPA. (BPA in food packaging was banned more than 10 years ago by the Japanese government, which gives you an idea of how far behind the curve we are.) A study by the Environmental Working Group found that almost all leading brands of liquid baby formula have BPA in their packaging. However, you’ll reduce your baby’s exposure by using powdered formula (they expose a child to eight to 20 times less BPA because less BPA lining is used in cans that contain powder) and by opting for packages that are made mostly from cardboard. Some containers are metal, which means the entire inside surface has BPA. Nestlé has said there is no BPA in the cans used to package its powdered formulas, but the Environmental Working Group says the company never backed up its claim with documentation. And Similac has recently stated that all of its powdered formulas are BPA-free.

Even so, make sure the formula you choose is milk-based. And of course, if you can…

Breast-feed

Another study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that perchlorate, a chemical used in rocket fuel, is showing up in baby formula—especially cow-milk-based

formulas. Perchlorate has also been found in breast milk: According to a 2005 study, researchers at Texas Tech University detected levels of perchlorate in breast milk as high as 10.5 micrograms per liter. The ubiquitous chemical is found in ground water, which is why you should…

Filter your water

The best way to eliminate obesogens from your tap water is to use an activated carbon water filter. Available for faucets and pitchers, and as under-the-sink units, these filters remove most pesticides and industrial pollutants. Check the label to make sure the filter meets the NSF/American National Standards Institute’s standard 53, indicating that it treats water for both health and aesthetic concerns. Try the Brita Aqualux ($28, brita.com), Pur Horizontal faucet filter ($49, purwaterfilter.com), or Kenmore’s under-the-sink system ($48, kenmore.com). However, if you have perchlorate in your water (you can find out by asking your municipal water supplier for a copy of its most recent water-quality report), you’ll need a reverse osmosis filter. But for every 5 gallons of treated water they create per day, they discharge 40 to 90 gallons of wastewater, so make sure it’s necessary before purchasing one.

Make your own baby food

Health Canada tested baby food bottled in glass and found BPA in 81 percent of the samples. While glass doesn’t contain BPA, the chemical leaches from the plastic liners of metal jar lids. Instead of buying expensive baby food, buy a hand blender and make your own from organic fruits and vegetables. Simply steam or boil organic produce, put it in a bowl with a little water, and then blend until smooth. You can do the same with meats when your child is old enough.

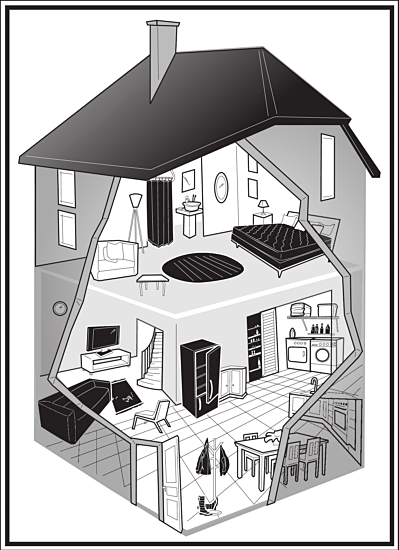

Your Big Fat House

Obesity-causing chemicals have invaded our homes. It’s up to you to kick them out.

* Bedroom

Carpet (PBDEs), vinyl flooring (PVC), mattress (PBDEs), toys (BPA), waterproof clothing (Phthalates, PFOA) One study found that children who live in homes with vinyl flooring in the bedrooms are twice as likely to have autism. To further avoid EDCs in your bedroom: 1. Make sure the mattresses and mattress covers you buy aren’t treated with brominated flame retardants. 2. Avoid clothing that’s been coated with a water-, stain-, or dirt-repellent. 3. Throw out plastic toys that aren’t designated “BPA free” (old plastic leaches more toxins). 4. Buy PVC-free, BPA-free, and phthalate-free toys. You can find some at thesoftlanding.com.

* Foyer

Raincoats (phthalates), rain boots (phthalates), faux leather coats, shoes, purses, and briefcases (phthalates) PVC might be an obvious component of rain slickers and Wellies, but the phthalate-laden material is almost always found in soft fake-leather accessories as well. To avoid exposure: 1. Buy real leather accessories. 2. Try waxed canvas rain gear instead.

* Laundry Room

PVC pipes, detergents, dryer sheets (phthalates) Most cleaning products contain phthalates, and their containers have BPA. But SC Johnson, the maker of Windex, Shout, Pledge, and Scrubbing Bubbles cleaning products, has started to list ingredients on its products and began a two-year program in 2008 to phase out phthalates from its products. So far, other major manufacturers have not followed SC Johnson’s lead. In order to make your cleaning area cleaner: 1. Buy fragrancefree cleaning products. 2. To reduce the amount of laundry detergent you need to use, add baking soda: It softens the water, increasing the detergent’s power, according to the Center for Health, Environment, & Justice.

* Living Room

Carpet (PBDEs), air fresheners (phthalates), furniture (PBDEs), electronics (PBDEs) Flame retardants (PBDEs) are especially harmful to children. Human exposure comes from contact with treated products such as electronics, but the majority of our exposure is from dust. A recent study found that the average level of PBDEs in dust is more than 4,600 parts per billion. To reduce exposure: 1. Choose electronic brands that don’t contain PBDEs. 2. Use a HEPA-filter vacuum to trap the most dust particles. 3. Open your windows when vacuuming and make sure your home has good ventilation.

* Bathroom

Toothbrush (BPA), toothpaste, vinyl shower curtain, water from the shower comes through PVC pipes, soaps, shampoos, deodorants, creams, powders, and makeup (phthalates), nail polish (phthalates, PFOA) Bathrooms can shower you in EDCs, literally. Most soaps, lotions, and deodorants contain phthalates, listed on the ingredients as “fragrance.” To decrease the toxicity of your bathroom experience: 1. Buy fragrance-free personal-care products (deodorant or hand/face cream). 2. Use only two personal-care products at 3. a time, which one study showed reduced people’s phthalate concentrations fourfold. Buy PVC-free shower curtains. 4. Put a filter on water taps to reduce exposure to toxins in your water.

* Kitchen Produce in the fridge (pesticides), meat in the freezer (PBDEs, PCBs, pesticides), canned food in the pantry (BPA), jars of peanut butter (phthalates), jars of tomato sauce (phthalates), jarred baby food (BPA), plastic cups, baby bottles, plates, and utensils (BPA) To reduce your exposure: 1. Choose plastics with recycling code 1, 2, or 5. Recycling codes 3 and 7 are more likely to contain BPA or phthalates. 2. Use glass baby bottles. 3. Heat foods in glass, not plastic. 4. Use bamboo, glass, Pyrex, stainless steel, and cast-iron cookware. 5. Buy organic versions of the Dirty Dozen fruits and vegetables, as well as organic dairy and pasture-raised meats.

Find out more about synthetic obesogens on page 266.

BAD CHEMISTRY A quick look at the most common synthetic obesogens*

Bisphenol-A

A synthetic estrogen found in safety equipment, eyeglasses, computer and cellphone casings, water and beverage bottles, plastic toys, glass bottle lids, jarred foods, canned foods, epoxy paint and coatings, dental composites and sealants, and pesticides. BPA has been linked to be hav ioral problems, brain abnormalities, reproductive problems, diabetes, and obesity.

Phthalates

A group of industrial chemicals used to make plastics, including polyvinyl chloride (PVC), more flexible or resilient; also used as solvents. They’re found in food packaging, plastic toys, air fresheners, raincoats, vinyl shower curtains, vinyl flooring, wall coverings, and other consumer goods. Also, if the term “fragrance” is used in a product’s ingredient list, it probably contains phthalates. Phthalates have been linked to reproductive problems, birth defects, brain abnormalities, diabetes, and obesity.

Pesticides

Many pesticides—such as organochlorines, DDT (and its breakdown, DDE), atrazine (one of the most widely used weed killers), vinclozolin (a fungicide), tributyltin (used in ship paint, found in fish), carbendazim (a fungicide), HPTE (a breakdown product of a widely used insecticide), triclosan (found in antibacterial soaps)—are endocrine disruptors. Pesticides have been linked to reproduction and fertility problems, birth defects, and obesity.

PBDEs

Flame retardants added to textiles, furniture, plastics, car interiors, and electronics. These known endocrine disruptors leach out of products and into the environment. One Environmental Working Group study found 11 different flame retardants in a group of children ages 18 months to 4 years old. PBDEs have been linked to permanent learning and memory impairment, behavioral changes, decreased sperm count, and fetal malformations.

PCBs

Polychlorinated biphenyls were banned in 1977, but they have lingered in our environment, leaching from landfills and industrial waste. PCBs still show up in our meat and fish and, because they cling to fatty tissue, accumulate in our bodies. They have been linked to low IQ, altered nerve function, behavioral problems, diabetes, and obesity.

PFOA

Perfluorooctanoic acid is a chemical used in manufacturing Teflon, Gore-Tex, Stainmaster, Scotchgard, and other nonstick and stain-resistant coatings. It’s also found in packaging that needs to be oil-and heat-resistant, like microwave popcorn bags and pizza boxes. It is found in the blood of most Americans and has been linked to birth defects, infertility, weight gain, and impaired learning and development.