When Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. first called his Boston peers “the Brahmin caste of New England,” he defined them gently. For “generation after generation,” Holmes wrote in 1860, this breed of “distinct organization and physiognomy” had composed a “harmless, inoffensive, untitled aristocracy.”

It’s even possible that Dr. Holmes believed that. But if the members of the deeply inbred Boston aristocracy who gathered around Beacon Hill and the Back Bay were truly harmless and inoffensive, it was partly because they perceived no wider world where harm might be inflicted or offense taken. Theirs was an intimacy of both blood and choice. They attended the same schools; they belonged to the same clubs. As children, dressed in velveteen, they all learned the quadrille at Signor Papanti’s dancing academy; as adults, traveling, they all stayed at the same hotels. “When the individuals of one group find a complete peace and happiness and fulfillment in the association with one another,” asked the narrator of John P. Marquand’s novel of Brahmin emotional austerity, The Late George Apley, “why should they look farther?” Henry Adams disagreed. Years after he permanently relocated to Washington, DC, in what could only be considered a vain attempt to flee his past, Adams identified a chronic ailment he called Bostonitis. It was, Adams wrote, an inflammation that arose from a sufferer “knowing too much of his neighbors, and thinking too much of himself.”

Grandson and great-grandson of presidents, a man whose pedigree on his father’s side was equaled in heft by the wealth that came down through his mother, Adams, in fact, approved of very little, himself included. His erudition was matched only by his cynicism, his eloquence by a sort of aesthetic dyspepsia that made him shrink into the past. Born in 1838, he nonetheless considered himself a child of the eighteenth century. By the time the twentieth century arrived and he had written the rumination on medieval Europe he called Mont Saint-Michel and Chartres, he had decided he belonged, instead, in the twelfth. But in the famous second sentence of The Education of Henry Adams, writing in the third person, Adams reached back yet further to locate himself. “Had he been born in Jerusalem under the shadow of the Temple and circumcised in the Synagogue by his uncle the high priest under the name of Israel Cohen,” he wrote, “he would scarcely have been more distinctly branded . . .” than he had been by the Boston he could never truly escape.

It was a telling image for the opening of the book that would forever define him. By the time he wrote The Education, which was published privately in 1907, Adams had succumbed to a convulsive anti-Semitism. In Paris during the treason trial of the falsely accused Alfred Dreyfus, he characterized the defendant as “a howling Jew.” A trip to Spain and Morocco led him to say he had “seen enough of Jews” and had come to the conclusion that the Spanish Inquisition was “noble.” Adams’s dear friend the statesman and diplomat John Hay, himself no ally of the new immigrants arriving on American shores, said that when Adams “saw Vesuvius reddening the midnight air he searched the horizon for a Jew stoking the fire.”

In The Education, Adams was marginally more careful with his animus. But his presentation of one particular Boston recollection might have made concrete what many of his fellow Brahmins perceived. If you try to put yourself in Adams’s place—taking into consideration his lineage, his wealth, the era in which he lived—you might be able to understand what he encountered, perhaps while crossing Boston Common. A man in his—what: twenties? thirties? fifties? It was impossible to tell. He wore a long black frock coat of cheap gabardine. His untamed beard spilled down the length of his chest, flakes of dandruff and lint and crumbs marking its path. His face, possibly pockmarked or otherwise scoured and turned ashen by malnutrition, was framed by side curls that fell to his collar. He probably smelled; a bathtub or washbasin was likely unavailable more than once a week to such a man. What Adams saw, he wrote, was “a Polish Jew fresh from Warsaw or Cracow . . . a furtive Yacoob or Ysaac still reeking of the Ghetto, snarling a weird Yiddish.” His Yacoob or Ysaac might as readily have been a Giuseppe from the parched farmland of Sicily, or perhaps a Zoltan from the crowded streets of Budapest, and they, too, might have provoked Adams’s reaction to the Polish Jew: the stranger’s presence in America, he wrote, made Adams identify with “the Indians or the buffalo who had been ejected from their heritage.” He wasn’t alone.

If Henry Cabot Lodge knew Francis Galton, the evidence is lost in the boundless and scattered correspondence of the latter and in the somewhat bowdlerized letters of the former. But Lodge—politician, scholar, memoirist, xenophobe—certainly knew Galton’s work; for one thing, they both published articles in the same journal. More to the point, though: in 1891, just months before Lodge first rose in Congress to urge limits on immigration, he used Galton-like analysis to prove the superiority of his own racial heritage. Taking inspiration from a British article that had sorted “intellect” by geography,I Lodge sifted through fifteen thousand names in a six-volume encyclopedia of American biography, sorted them by ethnicity and location, and concluded that men of English heritage from Massachusetts occupied the pinnacle of American “ability.” Conveniently, there was probably no one more English in heritage nor more firmly planted in the Massachusetts soil than Lodge himself.

There wasn’t a box on the Brahmin checklist he didn’t tick: Colonial ancestry. Cousined marriage. Generations of engagement, root and branch, with Harvard. A web of familial connections to everyone else who mattered in Boston (including Elizabeth Higginson Cabot, “the common grandmother,” as one of her descendants had it, of “Cabots, Jacksons, Lees, Storrows, Paines and other Boston families”). A family seafaring fortune derived in part from trade in opium and slaves wasn’t uncommon in Brahmin Boston, either. The subject of Lodge’s first book was his great-grandfather George Cabot, who made his name as a Federalist politician, acquired his wealth as a privateer, and forged his politics from a deep loathing for both the French Revolution and the democratic ideas of Thomas Jefferson. Thomas B. Reed, a Mainer who was Speaker of the House for six years, acknowledged that his friend Lodge arose from “thin soil, highly cultivated.” Elected to Congress in 1886, Lodge in 1892 entered the Senate, where he would serve six terms. Few politicians stood taller than Henry Cabot Lodge in the politics of late-nineteenth- and earlier-twentieth-century New England, and no one was more certain of his inborn claim to his eminence.

The most memorable accomplishment of Lodge’s career was undoubtedly his relentless and successful campaign to shatter Woodrow Wilson’s post–World War I dream by keeping the United States out of the League of Nations. But historian George E. Mowry’s precise assessment of Lodge could have applied at any point in his decades as a public figure: he was “one of the best informed statesmen of his time . . . an excellent parliamentarian [with] a mind that was at once razor sharp and devoid of much of the moral cant typical of the age.” Mowry’s appraisal of Lodge’s personality was equally acute: “He was opportunistic, selfish, jealous, condescending, supercilious. . . . Most of his colleagues of both parties disliked him, and many distrusted him.” When he was defeated for reelection to the Harvard Board of Overseers in 1890—probably as unkind a cut as someone like Lodge could suffer—a commentator said, “The fact is Mr. Lodge’s best friends . . . have been disgusted” by his dedication to his own self-interest.

Assessing his patrician bearing, another contemporary said one could “throw a cloak over Lodge’s left shoulder and he would step into a Velázquez group in the Prado and be authentic.” But reality can eclipse imagination. The superb three-quarter-length portrait of the forty-year-old Lodge that John Singer Sargent painted in 1890, eventually a prized possession of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, captures him at the very moment he began his Galton-like search for the correlation between ethnicity and talent in that six-volume biographical dictionary. In his vested suit, the fingers of his right hand engaged with his gold watch fob, Lodge emanates a glacial hauteur, his lips tight and severe, his eyes cast with imperious disregard toward some distant point off the canvas. Studying it, you could reasonably feel that you are despoiling him by your very presence. And if the faraway look suggests that he’s contemplating the inevitable decline of aristocratic privilege, that would be appropriate as well.

The faint rosiness that Sargent applied to his cheeks provides the only clue that there might be a different Lodge—the one so loyal to his mother, to whom he wrote weekly whenever they were in different cities; so beloved by his much admired wife, Nannie (more formally: Anna Cabot Mills Davis Lodge); and so treasured by his best friend, the gregarious and companionable Theodore Roosevelt. To the public he was Mr. Lodge; to his Brahmin friends he was “Cabot.” His intimates, though, called him “Pinky,” indicating that somewhere, encased deep within this icy enclosure, there resided at least the potential for human feeling.

As much as Lodge was a creature of Boston, even more was he swaddled in the fabric of an extreme form of Anglo-Saxonism. Early Anglo-Saxon law had been the subject of his doctoral dissertation (his was one of the first PhDs in political science granted by Harvard). He divined that his own ancestry went back to the Norman invaders led by William the Conqueror in 1066. To Lodge’s mind they were unquestionably “the most remarkable of all people who poured out of the Germanic forests.”

Though his racial views came to him naturally, at least one association helped intensify them: in 1873 the editor of the North American Review, who had been his teacher at Harvard, invited Lodge to join him as assistant editor. The North American was virtually the private journal of the Brahmin intelligentsia, its circulation minuscule, its contents an expression of the worldviews of the learned Bostonians who had been its editors, among them Edward Everett, Charles Eliot Norton, and James Russell Lowell. Next in this starry line of succession was the man who offered the job to Lodge: Henry Adams, who may have seen his protégé as a potential successor. Adams valued his energy, admired his intellect, and perhaps thought Lodge could alleviate what Adams described as his own “terror”: that the North American would “die on my hands or go to some Jew.”

In the event, the North American went to a Mayflower descendant who transplanted it immediately to New York. Adams left Boston permanently for Washington, and Lodge devoted the rest of his life to politics and writing. In the late 1880s, around the same time that Francis Galton first published in the North American, Lodge returned to the magazine as an occasional contributor—most notably in an 1891 article that proclaimed it was time to “guard our civilization against an infusion which seems to threaten deterioration.” The article’s title signified what soon became Lodge’s preeminent cause: “The Restriction of Immigration.”

Henry Cabot Lodge was the perfect specimen of that class of Brahmins afflicted by Adams’s Bostonitis. Joe Lee, equally wellborn, was in most ways his opposite. They were related, of course (it was Lee who had characterized Elizabeth Higginson Cabot as their breed’s “common grandmother”), and they both laid claim to Beacon Hill, Harvard, and great wealth. (“Cabots without money are a queer species,” Lee once said.) But where Lodge was imperious, Lee had a common touch that made him the most beloved of Bostonians. The fact that Lodge, like most of his class, was a lifelong Republican and Lee an eternal Democrat barely hinted at their differences. Lee—always Joe, never Joseph—battled the era’s plutocrats, kept a copy of Marx’s Das Kapital in his bedroom, and devoted his entire adult life to the support, financial and otherwise, of the principles he believed in.

In Lee’s handsome brick house on Beacon Hill, said a friend, “not a day passed without some good deed being done it.” Among Lee’s many beneficences was the Massachusetts Civic League, which he served, said an admirer, as “founder, official head, leading spirit and generous and constant supporter” (his support included the gift of a nearby bowfront federal-era row house to serve as league headquarters). His role with the Associated Charities of Boston, Lee once said, was “Chairman of the Committee on Difficult Problems,” a description he relished. Nationally, he was known as the “Father of the American Playground,” the result of his lifelong commitment to children’s activities. He poured large sums into such organizations as Community Service of Boston and into the Kowaliga School, a training academy run by and for blacks in central Alabama, and small sums into projects as varied as the English Folk Dance Society and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. He forswore his interest in the family’s magnificent estate in Beverly Farms, on Boston’s North Shore, and spent summers instead in a small beach house on the South Shore, in Cohasset. His idea of entertainment was reading Emerson out loud to his children. On at least one occasion this so excited him that he felt compelled to take a walk to ease the stimulation of the experience. The first important article Lee ever published (and he published nearly as frequently as he breathed) was entitled “Expensive Living—The Blight on America.” Once, after he sent a $25,000 donation to Harvard, Lee asked a friend the next day whether it made sense for him to spend $6.50 on a mooring stone for his boat.

Boston adored him. Newspapers extolled his “helpful, sympathetic spirit,” his “brotherly smile.” He was “whimsical and unusual,” a lifelong friend recalled, “extremely original in his personality—he was just Joe, there was no one like him.” Tall and thin, bright of eye and quick to smile, he “was the life of the party without telling jokes or stories or making any effort on his part to be jolly. He was just plain pleasure to have around and lent something intangible to any occasion.”

One chronicler of New England life called Lee “Boston’s most distinguished private citizen.” This was the sort of comment that had always made him squirm and that he would usually deflect with droll self-deprecation. At one testimonial dinner, as speaker after speaker offered arias of praise, Lee turned to a companion and whispered, “They are trying to make me out a personage.”

The only elective office Joe Lee ever held was a seat on the Boston School Committee, where he could sidestep the dismal factional politics of the day to effect radical change. Soon the city’s schoolchildren had annual dental examinations and periodic physicals. Single-handedly, Lee “put the law governing the Extended Use of Schools on the books,” said his fellow committee member Judge Michael H. Sullivan. The Extended Use law effectively turned the city’s schools, previously a tumultuous clatter of Italians, Irish, Russian Jews, and innumerable other nationalities, into a shared cultural, civic, and recreational asset for all Bostonians. Debates and lectures, dance and music presentations, athletic events and other programs: Could there have been a better way of bringing together polyglot Boston, where 74 percent of the population in 1910 were either immigrants or children of immigrants?

Probably not. But if Joe Lee had truly had a choice, he would have wished the polyglot crowds out of existence, or at least out of Boston. For the one political cause to which this friend of the common man devoted the most time, money, and sheer fervor for more than twenty years was the movement to restrict immigration. When a measure was introduced in the Massachusetts legislature to provide working immigrants with evening sessions for citizenship proceedings, he called it “a vicious naturalization bill.” He feared that “all Europe” might soon be “drained of Jews—to its benefit no doubt but not to ours.” And in a letter to one of his closest associates he declared that “the Catholic Church is a great evil”; revealed his fear that the United States might “become a Dago nation”; and needed only six words to explain the necessary preventive strategy: “I believe in exclusion by race.”

* * *

THE ANTI-IMMIGRANT FIRE that began to consume the energies of both Lodge and Lee in the 1890s was hardly confined to Beacon Hill, nor was it new; the country’s uncomfortable engagement with immigrants had deep roots. The Europeans flocking to America, a well-known editor wrote in 1753, “are generally the most stupid sort of their own nation,” and unless they are turned away they “will soon so outnumber us” that the English language would be imperiled. Those immigrants were German; the offended writer was Benjamin Franklin.

American xenophobia was off to a good start. For decades to come, attitudes toward immigrants formed a perfect sine wave, periods of welcoming inclusiveness alternating with years of scowling antipathy. Early on, though, nascent bias lurked behind a seemingly open door. At the Constitutional Convention in 1787, James Madison made the case for immigration as an engine of national growth and prosperity. Yet at the same time schoolchildren were learning from the ubiquitous New-England Primer to “abhor that arrant Whore of Rome,” the Catholic Church.II In the 1830s Samuel F. B. Morse, already a well-known painter but not yet celebrated as the inventor of the telegraph, published a rant titled Foreign Conspiracy Against the Liberties of the United States, assaulting the “body of foreigners . . . held completely under control of a foreign power” that had sent them here to create a Catholic theocracy. But even then, the young nation continued to absorb without evident pain the relative trickle of immigrants—by most measures barely a million, all told, in the five decades following ratification of the Constitution.

But when the Phytophthora infestans fungus devoured the Irish potato crop in the 1840s, hundreds of thousands beset by famine fled to America. Not long after, emigration from Germany accelerated in the wake of the failed revolutions of 1848. Total immigration between 1851 and 1860 alone spiked to more than 2.5 million. The response was so intense and swift that a political party devoted to an extreme form of nativism was able to elect five U.S. senators, forty-three House members, and seven governors within six years of its founding. Originally organized as the secret Order of the Star Spangled Banner, then officially known as the American Party, its more familiar name arose after members were instructed, when asked about the group, to say “I know nothing.” But the Know Nothings did not hide their goals. In Massachusetts, a Know Nothing governor was elected to three terms beginning in 1854 and led an eagerly compliant legislature to enact a law denying the vote to those who could not read and write in English—even if they had already been naturalized as citizens. To twenty-first-century eyes, any overlap between New England’s nineteenth-century abolitionists and its immigration restrictionists might appear to be counterintuitive. But among the antislavery campaigners it was not at all unlikely: many agreed with Frederick Douglass, who in 1855 condemned a system that allowed “the colored people [to be] elbowed out of employment” by European immigrants.

Labor surpluses were at the very heart of much of the restrictionism that continued to seethe throughout the rest of the nineteenth century (and would recur periodically well into the twenty-first). But when the labor market was tight, principles were loosened. During the Civil War, when the Union’s need for both the instruments of war and the men who would wage it turned surpluses into severe shortages, Abraham Lincoln asked Congress to find a way to increase immigration. The nation, he said, could tap into the “tens of thousands of persons, destitute of remunerative occupations” who were “thronging our foreign consulates and offering to emigrate to the United States.” Congress quickly obliged, passing “an act to encourage immigration” in 1864.

Operating under this authorization, the American Emigrant Company sent its agents abroad, largely to England and the Scandinavian countries, to recruit laborers on behalf of mining companies and other businesses suffering manpower shortages. Employers were obliged to pay the AEC for the immigrants’ passage across the Atlantic (a voyage conducted, the advertisements promised, “with the most careful regard to comfort and safety”), and the immigrants were obliged in turn to repay their employers from their wages. One of the founders of this venture in “contract labor”—a rather more benign term than the equally accurate “indentured servitude”—was a former senator from Connecticut; its supporters included several exemplary abolitionists who did not share Frederick Douglass’s concerns, among them Charles Sumner and Henry Ward Beecher.

Until the brief life of the 1864 act (postwar recession led to its revocation in 1868), the federal government had kept its hands off immigration policy. But by the early 1880s, two factors compelled Congress to seize control of the issue. The first—the patchwork of state laws and regulations, particularly involving per capita “head taxes” that were meant to cover the cost of newly necessary social services—was largely procedural.III The second was driven by—there’s no other word for it—race hatred.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which halted immigration of all “skilled and unskilled [Chinese] laborers,” arose from the boiling resentment toward Chinese immigrants that dated back to their initial arrival in large numbers in the wake of the 1849 gold rush, numbers soon amplified by the railroad companies’ ravening hunger for cheap labor. (“Why should I pay a fireman six dollars a day for work that a Chinaman would do for fifty cents?” asked James J. Hill of the Northern Pacific.) As early as 1854 it was unlawful in California for a Chinese person to testify in court against a white. In 1878 the U.S. Supreme Court barred Chinese and other Asian immigrants from citizenship. The Fifteenth Amendment, enacted just eight years earlier, had eliminated race as a criterion for denying citizens the right to vote—but it said nothing about the right to citizenship itself.

Americans of the era, especially in the western states, harbored what one newspaperman called an “instinctive hatred of the Chinese,” and the 1882 law—extended in 1892, made permanent in 1902, and anchored in legislative and judicial cement until 1943—institutionalized it. It also provided implicit sanction for immigration opponents to base their arguments not solely on the labor issues that underpinned the statute but on notions of racial inferiority. American Federation of Labor president Samuel Gompers, who would hold his anti-immigration stance unflinchingly for decades (though himself an immigrant Jew from England), could say that the Chinese “have no standard of morals.” The editor of the Fresno Republican could call the Chinese “biped domestic animals in the white man’s service.” When sociologist Edward Alsworth Ross, a prominent progressive academic who would become one of the leading intellectual patrons of the immigration restriction movement, made the case for excluding Chinese laborers, he did not flinch from invoking racial characteristics: “the yellow man” is a threat to the white man, he wrote, “because he can better endure spoiled food, poor clothing, foul air, noise, heat, dirt, discomfort, and microbes. Reilly can [outwork] Ah-San, but Ah-San can underlive Reilly.”

The rising numbers of Chinese immigrants might have posed a problem in the western states, but to most New Englanders they might as well have been populating the moon (Henry Cabot Lodge’s idea of the West, said a political associate, was Pittsfield, Massachusetts). Boston’s eyes were cast east, toward the polyglot jumble of Austria-Hungary, the vast reaches of the Russian Empire, the impoverished villages of southern Italy. In 1882 fewer than 15 percent of European immigrants came from the regions east of Germany and south of present-day Austria. Then everything changed.

Factors both general and specific initiated the explosion in immigration that would accelerate so powerfully for the next forty years. The relative infrequency of war in the post-Napoleonic era, a decline in the infant death rate, and in some countries the gradual spread of sanitary practices had more than doubled the population of Europe in less than a century. The weblike spread of railroads across the continent had made ocean ports accessible, and the age of steam had increased the speed of transatlantic passage and the capacity of the ships making the voyage.

Those were by and large salutary changes. Others, however, were cruel. In 1881 the assassination of Czar Alexander II became the ostensible justification for an unchecked wave of pogroms inflicted on Jews in the Russian Empire, compounding the already straitened circumstances that had long circumscribed their lives. The anti-Semitic May Laws of 1882 placed restrictions on the right of Jews to settle in certain areas and on their freedom to conduct business. By one estimate, total Russian Jewish immigration to the United States in the 1880s leapt to 140,000, a sevenfold increase from the previous decade. In southern Italy, desperate poverty and the remnants of medieval vassalage were made combustible by a cholera epidemic that killed more than 50,000 and provoked widespread panic and flight. In 1877 only 3,600 Italians immigrated to the United States; by 1887 the annual number had increased more than twelvefold. In the same period, Polish immigration multiplied by fifteen times, Hungarian by twenty-six. Greeks, Serbs, Slovaks, Ukrainians, Albanians, Ruthenians—it was as if all of eastern Europe were emptying out. In 1888 the American Economic Association, taking note, announced a prize contest: $150 for the best essay on “The Evil Effects of Unrestricted Immigration.”

It was around this same time that patrician Bostonians took note of the changing nature of immigration and realized that this new wave was different from the earlier one they had experienced—and they had hardly tolerated that one. The first refugees from the Irish potato famine had begun to arrive in Boston Harbor in 1845. Ten years later, the city was 20 percent Irish. In the eyes of the Unitarian abolitionist Theodore Parker—he was one of the so-called Secret Six who financed John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry—the “American Athens” was becoming the “American Dublin.” Charles Francis Adams Jr., Henry’s older brother, railed against universal suffrage, predicting a “government of ignorance and vice [dominated by] a European, and especially Celtic, proletariat on the Atlantic Coast.”IV Charles Eliot Norton—a man of unchallenged cultivation and worldliness, friend to Charles Darwin, committed reformer, admired scholar—wistfully invoked the “higher and pleasanter level” of New England “before the invasion of the Irish.” But in 1884 Boston elected its first Irish mayor, and only those afflicted by a willful social blindness could not see the city’s political future.

Still, as conscious of (and even as repelled by) the Irish as the Brahmins were, they knew them, or at least believed that the relationship between an employer and his servants yielded meaningful knowledge. That both groups spoke the same language was not an uncomplicated truth; on the other side of the Atlantic, their respective forebears had been locked in the uneasy embrace of colonizer and colonized since the time of Henry VIII. But when one insulted the other, which they did with equal passion, translation was unnecessary.

Then came Adams’s furtive, reeking, snarling Yacoob and Ysaac. And Giuseppe and Luigi and Mario, Janos and Miloslav and Leszek. The so-called new immigration from eastern and southern Europe that began to gather momentum in the early 1880s would change Boston nearly as much as the Irish immigration had. By 1900 more than 400,000 Bostonians, out of a population of 560,000, had at least one foreign-born parent. The city’s North and West Ends became swarming hives of strange sounds, strange smells, strange people. African Americans had lived in the West End for decades, and though abolitionist ardor rarely extended to any commitment to social equality, the city’s black population was at least familiar. The newcomers were an invasive species. “No sound of English, in a single instance, escaped their lips,” an astonished Henry James wrote after visiting Boston for the first time in twenty years. The recent Italian immigrants James encountered on Boston Common were “gross little aliens.” Sociologist Frederick A. Bushee was horrified: “There are actually streets in the West End, while Jews are moving in, negro housewives are gathering up their skirts and seeking a more spotless environment.”

The poverty that had compelled the immigrants to leave their homelands and endure a transatlantic crossing in steerage was nearly unimaginable. In his futurist novel Looking Backward, published in 1888, Edward Bellamy describes his time traveler, Julian West, encountering “pale babies gasping out their lives amid sultry stenches, of hopeless faced women deformed by hardship.” When Julian tries to bring this “festering mass of human wretchedness” to the attention of a group of wealthy Bostonians gathered at an elegant dinner party in a Commonwealth Avenue mansion, barely a mile away from “streets and alleys that reeked with the effluvia of a slave ship’s between-decks,” they are indifferent. “Do none of you know what sights the sun and stars look down on in this city,” he cries, “that you can think and talk of anything else? Do you not know that close to your doors a great multitude of men and women, flesh of your flesh, live lives that are one agony from birth to death?”

They did not. Dr. Richard Clarke Cabot—another cousin of both Lodge and Lee—was a staff physician at Massachusetts General Hospital (and taught social ethics at Harvard on the side). MGH was perched at the edge of the West End, and a typical day would bring thirty patients through his office. On one such day, Cabot experienced a sort of Brahmin epiphany. “Abraham Cohen, of Salem Street, approaches, and sits down to tell me the tale of his sufferings,” Cabot wrote. “The chances are ten to one that I shall look out of my eyes and see, not Abraham Cohen, but a Jew; not the sharp clear outlines of this unique sufferer, but the vague, misty composite photograph of all the hundreds of Jews who in the past ten years have shuffled up to me with bent back and deprecating eyes. I see a Jew,—a nervous, complaining, whimpering Jew,—with his beard upon his chest and the inevitable dirty black frock-coat flapping about his knees. I do not see this man at all. I merge him in the hazy background of the average Jew.”

Cabot’s sudden awakening was profound in its effect. He would soon bring the first Jewish doctors onto MGH’s staff (when the hospital was already 101 years old, he noted dyspeptically), and also served as head of the medical staff at the city’s first Jewish hospital. But his encounter with Mr. Cohen of Salem Street illustrated the relationship between the old Boston and the new. To wellborn Bostonians of the 1880s and 1890s, the immigrants in their midst were simultaneously invisible and in plain sight. “The trouble with Boston,” Charles Francis Adams Jr. insisted, “is that there is no current of outside life everlastingly flowing in and passing out.” The presence of the immigrants was palpable, but their substance was not.

“THE DUDE OF NAHANT”V—that’s what Henry Cabot Lodge was called early in his public life, after both his manner and the narrow finger of land north of Boston that he considered his “ancestral acres.” Other epithets quickly adhered to him as he began to climb the political ladder, first as a member of the Massachusetts legislature, then in his campaigns for Congress in the 1880s: “Lah-de-Dah” Lodge, “the Silver Spoon Young Man.” But it would be unfair to suggest that Lodge was nothing more than a pampered aristocrat who wore his narrow racism as securely as he did the eight-button vest in Sargent’s portrait. The same sort of reform instincts that inspired Joe Lee harmonized with something deep within the Brahmin soul and resonated with Lodge as well. Seeming contradictions occupied the same mind comfortably. Celebrant of inherited privilege, Lodge was also Congress’s most fervent advocate for the meritocracy of the civil service. “Although rich by any standard,” a biographer wrote, “he had an aristocratic disdain for what were called in that day ‘robber barons.’ ” Assailant of the immigrant “other,” Lodge’s advocacy of black voting rights was unshakable.

Still, the posture Lodge assumed when, in 1891, he began his campaign for the mandatory use of a literacy test to screen out unworthy immigrants was a peculiar one. The idea of a literacy test was initially put forward by Edward W. Bemis, a socialist economist and labor union advocate, in an obscure Massachusetts theological journal. Bemis was not above a little Anglo-Saxon chest-thumping (“vigorous New England stock . . . hardy yeomanry . . . best elements of English life”) but his argument was in both its general thrust and its particulars almost exclusively economic: the immigration of unskilled workers lowered American wages. A literacy test requiring the immigrant to prove he could read in his native language was the surest way to weed out those unfit for anything but manual labor.

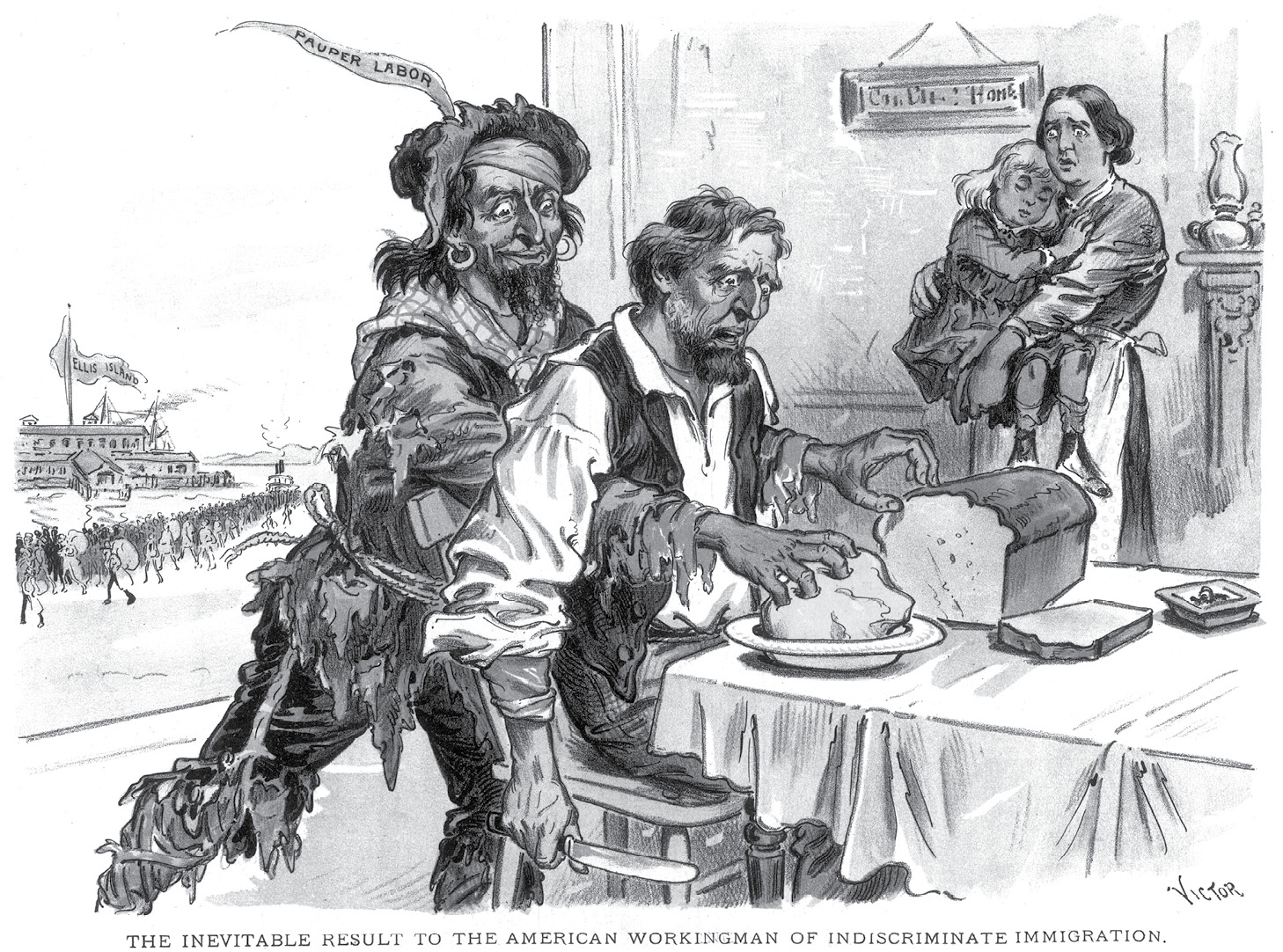

That apparently sounded useful to the well-tuned ears of an adept politician. The overriding reason for such a law, Lodge wrote in the North American Review, was to serve “as a protection and a help to our workingmen, who are more directly interested in this great question than any one else can possibly be.” When he introduced federal legislation mandating a literacy test for immigrants in February 1891, he asked the Congressional Record to append the article to his remarks from the House floor. It contained a litany of phrases that might have come from an American Federation of Labor brochure: “unskilled labor . . . flood of low-class labor . . . absolutely destroy good rates of wages . . . tendency toward a decline in wages . . . pulling down the wages of the working people . . . reducing the rates of wages . . . maintain the rate of American wages . . .” The Lah-de-Dah Dude of Nahant was now Henry Cabot Lodge, Friend of Labor.

A typical characterization of an Italian immigrant, from 1892.

Unlike Edward Bemis, though, Lodge was not content to let economics alone bear the burden of his desires. He knew that literacy rates in the impoverished regions of southern Italy and parts of the Jewish Pale of Settlement in western Russia and adjacent lands were exceedingly low, and thus exceedingly useful. “The immigration of people of those races which contributed to the settlement and development of the United States,” he said from the well of the House, “is declining in comparison with that of races far removed in thought and speech and blood from the men who have made this country what it is.” He wanted to “sift the chaff from the wheat.” America’s problems, he said, were “race problems.” If he’d had a copy of his recently published history of Boston at hand, he could have shared with his colleagues a sentiment he expressed in its pages with startling frankness: “Race pride or race prejudice, or whatever it may be called . . . has long since ceased to be harmful.” And, he added with a complacent flourish, “it has had other effects which have been of very real value.”

The comprehensive immigration bill Congress passed that session did not contain Lodge’s literacy test. Even so, the 1891 law was a landmark as imposing as the expanded immigration center on Ellis Island scheduled to open at the end of the year. The law formally placed all immigration policy and enforcement under federal control; ordered deportation of aliens who entered the country illegally; and provided for the rejection of “idiots, insane persons . . . persons suffering from a loathsome or a dangerous disease,” and various other undesirables, including polygamists. These were added to the list of those barred under previous laws, mainly convicts, paupers, and the equally despised Chinese.

To Lodge and others like him, the 1891 act was insufficient. But the debate did provide respectable cover for the expansion of anti-immigrant sentiment. Fearful of a multiplying “foreign vote,” the editors of The Nation warned that stricter tests needed to be applied either at the port of departure or the port of arrival, for if the immigrant “is once let loose, all precautions about him are idle.” The New York Times reported darkly on a violent “secret Polish society” in the Shenandoah Valley. A mob in New Orleans lynched eleven Italian immigrants, reputedly members of the Mafia, who had been accused—and then acquitted—of the murder of the city’s police chief. (Lodge shook an admonitory finger at the rioters but insisted that “such acts as the killing of these eleven Italians do not spring from nothing without reason or provocation” —namely “the utter carelessness with which we treat immigration in this country.”) Months later, when a few young Russian Jews were hired at a New Jersey glass factory, its workers embarked on three days of xenophobic riots.

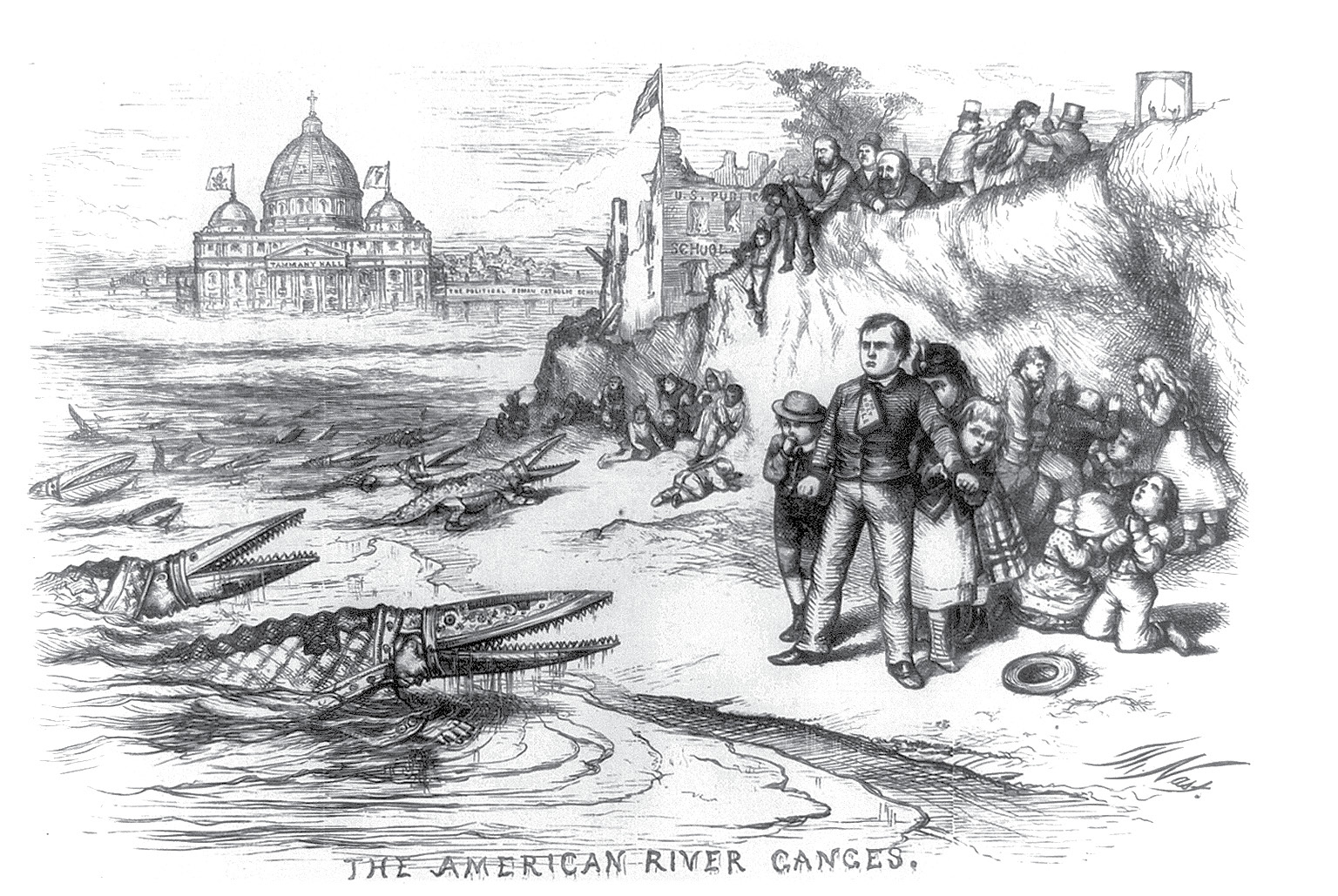

Thomas Nast cartoon, 1871: Catholic prelates perceived as amphibious beasts.

The financial panic that gripped the country that same year enabled the anti-Catholic American Protective Association to attain a membership approaching a million. The organization had been founded in Iowa in 1887 by a small-town lawyer convinced that Jesuits were “winding their fingers long and bony around the throat of this nation.” When a crowd of restrictionists was elected to Congress in 1894, the APA could claim plausible credit. For the literacy test—and for Lodge—the winds could not have been more favorable.

* * *

ON MAY 31, 1894, the day the Immigration Restriction League was born in a law office in downtown Boston, more than two thousand Italian immigrants gathered just a hundred yards away in historic Faneuil Hall, the “Cradle of Liberty,” to address a number of the problems they faced in their new country. Seven different immigrant organizations were represented. The main address in English was delivered by the secretary of the Massachusetts Society for Promoting Good Citizenship, who said, “As an American I desire to call attention of the city of Boston to the many abuses which these poor people have to suffer.”

The young men who met that same afternoon in the nearby law office on State Street thought such attention misplaced. This proved to be especially so for three of them, who would play instrumental roles in the organization created that day. All three had been classmates not only at Harvard (Class of ’89) but before that at G. W. C. Noble’s Classical School for Boys on Beacon Hill. All three were situated culturally, socially, and economically at the interlocked, self-contained, and impermeable center of the Boston patriciate. The meeting had been initiated by Robert DeCourcy Ward, whose ancestors had arrived in Boston with John Winthrop in 1630. Prescott Farnsworth Hall was part of what his wife described as one of “the old-time families [who] spent the winters in Boston and summers in Brookline”—which is to say that they would pack off for the country each June . . . and travel four miles west. But that signified wealth, not lineage, and Hall felt the need to establish his “old-time” credibility by invoking his direct descent from Charlemagne. The third cofounder, Charles Warren, needed only to trace his ancestry back to at least three passengers on the Mayflower.

As young as they were, Ward, Warren, and Hall were not without other distinctions. Ward, Harvard’s first professor of climatology, joined the faculty in 1891, at twenty-four. Later in life Warren would win the Pulitzer Prize for The Supreme Court in United States History. Hall never attained his classmates’ level of eminence, but this was not for want of effort; he engaged in several of the reform movements of the day and wrote books on landlord-tenant law. Apart from the restriction cause, Hall’s other passions included Wagnerian opera, Rosicrucianism, miraculous healing, and what he called “psychical research.” A lifelong depressive and insomniac raised by his invalid mother “like a hothouse plant” (said Hall’s wife), he was socially awkward, detached, unworldly. But of the three, he would make the greatest commitment to immigration restriction. One of his colleagues said “he did the work of ten men” to advance the cause.

Judging by Warren’s brief minutes of the first few meetings, one could explain the formation of the IRL with an adage common to the era: “no two Bostonians could have an idea in common without forming a club around it.” The league’s founders, none older than twenty-seven, might puff their chests with pride in their philosophical commitment (as the IRL constitution phrased it) to “the further judicious restriction or stricter regulation of immigration.” But if anything material was to come of it, they would have to reach beyond their own youthful circle.

At this, the men of the IRL were superb. To invoke another Boston aphorism, this one contrived by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., “No generalization is wholly true, not even this one”—but to say that the Brahmins and their close associates were receptive to the IRL’s argument was about as wholly true as a generalization could be. They recruited the widely admired historian and lecturer John Fiske to serve, at least nominally, as the league’s president. Boston’s leading philanthropist, Robert Treat Paine, signed on as a vice president, as did Henry Lee, Joe Lee’s father. Vice presidencies of organizations like the IRL were largely honorific, even if more so for the organization than for the individual: a group like the IRL could acquire an affirming aura from the shiny names on its letterhead.

One who chose to support the IRL financially, but on the condition that his name was not used, was John Murray Forbes. Possibly Boston’s wealthiest man, Forbes built his fortune in the Chinese opium trade, multiplied it in the railroad industry, then put it to use to support abolitionists and to finance publication of The Nation, which was founded in 1865 with his backing.

Forbes was in his eighties when Charles Warren asked him to join the IRL. Writing from Naushon Island, a seven-and-a-half-square-mile paradise off Cape Cod that Forbes had purchased in 1842 (and where his descendants continue to spend their summers 177 years later), Forbes prefaced his letter with an emphatically underscored “Strictly private.” In elegant longhand reaching down the page from a letterhead adorned with an engraving of a handsome yawl, five sails flying, Forbes promised financial support. He couldn’t have been clearer about the reason: “The great struggle . . . ,” Forbes told Warren, “centers on keeping our voting power and our reserves of public lands out of the reach . . . of the horde of half-educated and wholly unreliable foreigners now bribed to migrate here, who under our present system can be dumped down on us annually.”

True to Brahmin form, Forbes concluded his letter by asking Warren if he was “the son of our [customs] collector Winslow Warren, and thus closely connected with many of my intimate family friends of years past.” The Boston aristocracy was one family, and with very few exceptions the family was lined up against the tide of immigration.

Joe Lee had not been present at the founding meeting of the IRL, but his association with the organization was inevitable. He had tiptoed into charity work in his late twenties but still had not found the single driving passion he so earnestly sought; at twenty-seven he’d even traveled to Russia to seek advice from Leo Tolstoy, whom he found a “mere old crank” on philosophical questions (though he did enjoy their conversation about Beethoven). To Lee, there was no contradiction in his determination to improve the lot of Boston’s immigrant poor and his simultaneous wish to bar, or at least narrow, the door they entered through. Uneducated, unpropertied, and unwashed they might be, but the alien crowds bursting the bounds of Boston’s slums in the early 1890s were an intractable Fact, and they could not be expected to adapt without assistance. Charitable aid could be offered out of a sense of openhearted generosity, or it could emanate from a very different impulse: the conviction that whatever pestilence the immigrants brought—disease, crime, dependency, anarchy—was a contagion that, unchecked, would infect the entire city. Extending assistance to the immigrants in order to protect the privileges of the wealthy was hardly a paradox; it was simple self-preservation. For a classic progressive like Lee, helping the masses who were already here was just, and it was judicious. To keep more from arriving was at least the latter.

Lee was thirty-two and on a nine-month tour of Europe in 1894 when the immigration problem began to nag at him; he even wrote to an official at the Massachusetts State Board of Lunacy and Charity, requesting copies of the U.S. immigration laws. That same summer John F. Moors—one more cousin, who managed the family money and was probably Lee’s closest friend—wrote to tell Lee what the young men of the IRL were up to.

Lee had spent three weeks in St. Moritz to indulge in the essential Grand Tour luxury of “taking the baths,” a pause before traveling to London to indulge in a characteristic Joe Lee endeavor: discussing socialism and trade unions with various Englishmen. He wrote to Margaret Copley Cabot—yet another cousin, but in this instance soon to become his wife—and repeated Moors’s news: “There is a society started in Boston to do the work I thought of.” Less than a year later Prescott Hall, seeking funds, sent Lee a recent league publication that Hall considered the IRL “bible.” Its title was “Study These Figures and Draw Your Own Conclusions.” The figures indicated that the percentage of immigrants coming from northwestern Europe had dropped from 74 percent in 1869 to 48 percent in 1894, while the percentage coming from eastern Europe and Italy over the same period had soared from 1 percent to 42 percent.

If any readers of the IRL pamphlet had difficulty coming to the conclusion Hall desired, he might have directed them to a letter he sent to the Boston Herald in June 1894: “Shall we permit these inferior races to dilute the thrifty, capable Yankee blood . . . of the earlier immigrants?” This may have been the first public expression of the undergirding of the restriction movement: that the impoverished steerage passengers disgorged daily at the Long Wharf immigration station—and at Ellis Island down the coast in New York, and in Baltimore and Philadelphia and other port cities—were not merely different. They were biologically inferior.

Joe Lee didn’t sign on immediately, but this first direct contact with the IRL augured what was soon to come: a four-decade engagement with the league as its primary financial underwriter, its leading strategist, its personal emissary to four U.S. presidents. The Immigration Restriction League could not have existed without him.

* * *

ELEVATED TO THE SENATE IN 1892, Henry Cabot Lodge soon began his effort to reintroduce the literacy test, drawing support from the constituency he valued most: in a general sense, the people Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. had called Boston’s “sifted few.” Boston’s best had begun to declare themselves for restriction around the time that Phillips Brooks, the Episcopal bishop of Massachusetts who served as a sort of Brahmin moral conscience, joined the Sons of the American Revolution. It was an act, he said, meant to signify his belief that “our dear land at least used to be American.”VI Then along came the passionate young founders of the Immigration Restriction League and the name-brand officers they had recruited among the Boston elite. The IRL aligned itself with Lodge in what was effectively its first public action, the release of a fourteen-page pamphlet calling for an “educational test” to weed out the unwanted.

But it was someone Lodge had known and been allied with politically for two decades whose public support for restriction went far beyond decorating the stationery of the IRL with his name. Francis Amasa Walker’s array of credentials conferred an authority that Lodge, despite his political eminence and his writerly achievements, could not hope to attain: Civil War hero (wounded at Chancellorsville, retired as brigadier general), economist (“the favorite and obvious choice” to be first president of the American Economic Association), public servant (commissioner of Indian Affairs, director of the U.S. Census), and educator (first president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

Lodge may have previously referenced the “race problem,” but once clad in his help-the-workingman disguise he was required to make his racial points obliquely. Walker was as direct as a bullet. In an article in the Yale Review, he described the new immigrants as “vast masses of filth” who came from “every foul and stagnant pool of population in Europe.” Arguing for a $100 entry fee for all new immigrants—the 2019 equivalent of nearly $3,000—he made the case that such an amount “would not prevent tens of thousands of thrifty Swedes, Norwegians, Germans” and the like from entering, but would debar the impoverished multitudes of eastern and southern Europe. He drew on Jacob Riis’s compassionate account of life in the ghettoes of New York, How the Other Half Lives, not to evoke sympathy but to inspire loathing: the people Riis met were “living like swine.” They engaged in “systematic beggary at the doors of the rich” and “picking over the garbage barrels in our alleys.” In a footnote that was essentially an exasperated aside, Walker paused in his peroration to ask, “Will the reader trouble himself to remember by what sort of men and women this country was first settled?”

Surely not the people he later described with the five words that would be invoked repeatedly over the next quarter century by those who judged immigrants not by their worth as individuals but by the presumed deficiencies embedded in their ancestry. The immigrants filling the halls of Ellis Island, standing in queues on Long Wharf, and waiting expectantly at every other immigration portal, wrote this former head of the Census Bureau (who presumably ought to know), were “beaten men from beaten races.”

“Where Mrs. Lodge summoned, one followed with gratitude,” wrote Henry Adams, “and so it chanced that in August [1895] one found one’s self for the first time at Caen, Coutances, and Mont-Saint-Michel in Normandy.”

It was on this five-month voyage in the grand style (it also took in London and Spain) that Adams, traveling with the Lodges, discovered the mystical connection to the twelfth century he evoked in Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres. Lodge, in turn, found lavish evidence of the Norman brilliance he considered his inheritance—the cathedral at Amiens, the Bayeux Tapestries, Mont-Saint-Michel itself. On the other side of the racial ledger, he came up with his own version of Francis Walker’s epithet: traveling in Spain, Lodge determined that the “repellent” Spaniards were “a beaten & broken race.” He also discovered a recent book by the sociologist Gustave LeBon, Les Lois Psychologiques de l’Évolution des Peuples (published subsequently in English as The Psychology of Peoples). As Walker’s work would help free Lodge to express his xenophobic contempt without trimming his language, LeBon’s gave his arguments the illusion of scholarly gravity.

Gustave LeBon was a physician, anthropologist, and pathbreaking sociologist whose most enduring concept (praised by Freud, adapted by Hitler) was the mind—or, perhaps more accurately, the mindlessness—of “the crowd.” He also despised democracy, trembled at the thought of socialism, considered women biologically inferior, and believed the history of race explained the history of the world. Adams and the Lodges returned to the United States from their European journey in November 1895. Four months later, when Lodge rose to address the Senate about the need for a literacy test for all immigrants, he had internalized LeBon’s racial arguments so thoroughly one might have suspected a form of transatlantic ventriloquism.

Referring to the Frenchman as “a distinguished writer of the highest scientific training and attainments,” Lodge offered a hymn to “the qualities of the American people, whom [LeBon], as a man of science looking below the surface, rightly describes as homogeneous.” To make his case, he first treated his Senate colleagues to a capsule history of the Western world (“capsule” is actually the wrong word; it went on for paragraph after lengthy paragraph) that began with the Roman conquest, arched through the migrations of the Celtic and Germanic tribes, and then alit upon the Norsemen, ancestors of his own Norman forebears. “They came upon Europe in their long, low ships,” Lodge intoned, sounding more like a 1930s-era newsreel narrator than a Gilded Age politician, “a set of fighting pirates and buccaneers, and yet these same pirates brought with them out of the darkness and cold of the north a remarkable literature,” as well as “the marvels of Gothic architecture.” And, most important, “these people”—along with their British descendants, and the French Huguenots, and the Dutch and Swedes, and even the IrishVII—were “welded together and [then] made a new speech and a new race.”

There was no avoiding it: no longer making the slightest attempt to hedge his language or suppress his prejudices, Lodge told the Senate that a literacy test “will bear most heavily upon the Italians, Russians, Poles, Hungarians, and Asiatics, and very lightly, or not at all, upon English-speaking emigrants.” And, he argued, why should it be otherwise? “The races most affected by the illiteracy testVIII are those . . . with which the English-speaking people have never hitherto assimilated, and are alien to the great body of the people of the United States.” This was the crux of the campaign for the literacy test that would focus the immigration debate for nearly a quarter of a century, with Lodge as its primary champion, evangelist, and propagandist: the test was a simple device that could be used to keep out precisely those nationalities that Lodge wanted to keep out.

Lodge’s speeches were singular; no one else could possibly have delivered them. His voice, once likened to “the tearing of a bed sheet,” was reedy and metallic. His literary allusions—taken from Carlyle, Macaulay, Matthew Arnold—were recondite. He had the irksome habit of presenting his arguments like a demagogue engaging with followers hungry for confirmation, not evidence: “No one” desires the new immigrants; “everybody now admits” the wisdom of Chinese exclusion; “history teaches us” that “if a lower race mixes with a higher in sufficient numbers . . . the lower race will prevail.”

Now, as he approached the end of his speech, he cast aside allusion, stepped away from stipulation, and landed at the heart of his argument: keeping the nation open to the new immigrants posed the “single danger” that could devastate the “mental and moral qualities which make what we call our race.” He did not hold back: “The danger,” he declared, “has begun.”

But even then, Lodge wasn’t through. It was a reflection of the times, and also of Lodge’s literary inclinations, that he hoped to inspire the anti-immigration forces with a poem. Thirteen years earlier it was poetry that had, in a way, first set the terms of the immigration debate. Emma Lazarus had only recently awakened to the persecution of Jews in the Russian Empire when she was asked in 1883 to help raise money for the construction of the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal. By then, this nonobservant Jew (of purest Sephardic origin) had already been celebrated by Boston’s best. Ralph Waldo Emerson had invited the young poet to visit him in Concord. Henry James, living now in France, engaged her in friendly correspondence. And just two weeks after Lazarus first gave a public reading of the poem that would soon decorate the statue’s base—and that still expresses the statue’s essence—James Russell Lowell wrote to declare his admiration. To Lowell, whose anti-Semitic impulses were just as instinctive (if not quite as grotesque) as Henry Adams’s, Lazarus’s passionate invitation to “the huddled masses / yearning to breathe free” was nonetheless “just the right word to be said.” It gave the statue, he wrote, “a raison d’être.”

But it was the music of a very different immigration poem that heralded Henry Cabot Lodge’s raison on the Senate floor on March 16, 1896. Its author, Thomas Bailey Aldrich, was the worst sort of Boston snob, which is to say a late convert to the conventions of Beacon Hill and the Back Bay. Born in New Hampshire to a family of modest means, he’d made his early reputation in New York before settling into a five-story mansion (plus cupola) on Mount Vernon Street, just down the block from Joe Lee’s house. Like Lowell he served as editor of the Atlantic Monthly, and like Lowell he was venerated by Lodge as a paragon of Bostonian virtue.

Aldrich was also a poet and novelist of facile but evident gifts, and as Lodge seized leadership of the anti-immigration movement in Congress, Aldrich became its de facto laureate. His anthemic text, obviously a response to Lazarus, was called “Unguarded Gates.” No one described it more accurately than Aldrich himself, who said his poem was a “misanthropic” work expressing his “protest against America becoming a cesspool of Europe.” Following nineteen stirring lines proclaiming America an “enchanted land / . . . A later Eden planted in the wilds,” Aldrich gets to his point:

Wide open and unguarded stand our gates,

And through them presses a wild motley throng . . .

Flying the Old World’s poverty and scorn . . .

Accents of menace alien to our air . . .

O Liberty, white Goddess! Is it well

To leave the gates unguarded? . . .

Just as Lazarus’s “Give me your tired, your poor . . .” would come to serve and to inspire immigration advocates over the years, so would Lodge’s invocation of Aldrich’s unguarded gates still be invoked in the halls of Congress as those gates slammed shut nearly three decades later.

Lodge could not have asked for a better reception to his speech. His friend Theodore Roosevelt, the thirty-seven-year-old New York City police commissioner, wrote to tell him it was “an A-1 speech,” and that he had even written to France for copies of LeBon’s works. (Roosevelt was yet another cousin of Joe Lee’s, although in this case only by marriage.) Newspaper support in Boston was hearty (the Advertiser said the speech was “among the most scholarly and logical discussions [of immigration] in recent times”), and papers across the country picked up an item that likely would have delighted Lodge had he learned about it: members of the “Russian-Nihilistic Club” of Chicago burned him in effigy. He had even been able to keep out of his bill a measure introduced by his Massachusetts colleague Senator George F. Hoar that would have provided an exemption for refugees from war or political oppression.

The test Lodge’s bill proposed was really very simple: immigrants sixteen and older would have to prove their eligibility for entry into the country by reading five lines of the U.S. Constitution, translated into their own language. A provision exempting women from the test had been added in the House specifically to ensure the continued supply of maids, cooks, and other domestic servants. The House version of the bill also contained a clause, eventually deleted, requiring immigrants to “read and write the English language or the language of their native or resident country.” The Senate bill required only English “or some other language,” which didn’t please Herman J. Schultheis, a former member of a commission appointed to investigate immigration issues. “Any one may be able to read and write ‘some other language,’ ” he complained. “A Sicilian chimpanzee would be able to pass that, but would not be able to read and write in his native Italian.”

Lorenzo Danford of Ohio, the chairman of the House Immigration Committee, saw a similar problem involving a different immigrant group. He altered the bill’s wording specifically to keep out “a class of people who have been thrown on our shores . . . known as the Russian Jews”; neither Yiddish nor Hebrew being the language “of their native or resident country,” knowledge of neither one would have allowed admittance. Another House member, Stanyarne Wilson of South Carolina, made a cleverly winking argument for the bill when he described the “very races” the test would exclude: “We can not mention them by name, by statute, on grounds of public policy and of comity between nations, but . . . this act will accomplish the same purpose.” Unconstrained by concerns of comity or, really, anything else, lame duck representative Elijah A. Morse of Massachusetts, concluding his three terms in the House, was forthright: the new immigrants from “southern Europe, from Russia, from Italy, and from Greece [are] entirely a different class of immigrants, with a civilization, with wants and necessities, far below the American standard. And the purpose of this bill is to exclude that undesirable immigration.” How undesirable? Some of them, Morse added for the apparent benefit of the unconvinced, come to the United States with “little else than an alimentary canal and an appetite.”

But neither coy euphemism nor outright racial invective—nor a lopsided 217–36 vote in the House—could carry the day. On March 3, 1897, the very last day of his presidency, Grover Cleveland vetoed Lodge’s bill, and there were not enough votes in the Senate to override. The president (whose ancestors had been in the United States since the 1640s) had spoken sympathetically about immigrants as far back as the first of his annual messages to Congress in 1885, when he condemned mob action against Chinese workers in Wyoming. More recently, Cleveland had praised the new immigrants as “a hardy laboring class, accustomed and able” to earn a living. Now, in his veto message, he declared that the Lodge bill would mark “a radical departure from national policy.” To date, he continued, “We have encouraged those coming from foreign countries to cast their lot with us and join in the development of our vast domain, securing in return a share in the blessings of American citizenship.” On one point Lodge would have had to acknowledge, at least privately, that the president was right. The literacy test, said Cleveland, was merely “the pretext for exclusion.”

As Lodge prepared for the bill’s rebirth in the next session of Congress, he was certain the new president would support it. He had privately opposed William McKinley’s nomination for the presidency (and years later carefully deleted references to this opposition from his published correspondence) but drew confidence from McKinley’s inaugural address. Hatless on the steps of the Capitol, his pince-nez firmly in place, the new president read from a text that warned of the risks inherent in “a citizenship too ignorant to understand or too vicious to appreciate” American institutions. Editorialists assured readers that congressional action followed by McKinley’s speedy signature would soon put the literacy test into the statute books.

But political exigencies—a recovering economy, the rising ethnic vote, the efforts of some new opponents—intervened and were then compounded by legislative inertia. Some suspected McKinley himself of quietly working to kill the bill. Desperate in Boston, Prescott Hall managed to get on the president’s appointment calendar, and subsequently reported that McKinley might be using some of the league’s own language in his annual message to Congress. But when the document emerged two weeks later, not one of its twenty thousand words addressed immigration. Given a free pass by the popular new president, Congress exhaled and failed to act. Henry Cabot Lodge turned most of his attention to the war against Spain and other imperial adventures. The literacy test was dead. Shortly thereafter, it appeared, so was the Immigration Restriction League, which in 1899 voted to forgo an annual meeting, disbanded its executive committee, and donated its papers and records to the Boston Public Library.

Apart from Lodge and Thomas Bailey Aldrich himself, no one employed the image of gates unguarded more fervently than Prescott Hall, who over time would probably devote more hours, more effort, and more complete conviction to stopping immigration than any other individual. But the cofounder of the IRL could rarely enhance his passion with public action. Chronically neurasthenic, inherently private, beset by unabating insomnia and a morbid stew of other, vaguer ailments, Hall would turn inward in moments of crisis. And in at least one despairing moment, when it appeared that the literacy test or any other effective restriction legislation would be doomed by politics, he turned to poetry.

Unlike Lazarus, who extended her arms to welcome huddled masses, and unlike Aldrich, who sought to post sentries at the gates to keep those masses out, Hall didn’t bother with metaphor or imagery—or, for that matter, with euphemisms, or distinctions between the lettered and the illiterate, or anything else but the certitude of his own beliefs. He wrote:

Enough! Enough! We want no more

Of ye immigrant from a foreign shore

Already is our land o’er run

With toiler, beggar, thief and scum.

It was an argument of sorts, but on its own not a convincing one. The anti-immigration movement needed something more than slogans and poems and the loathing that inspired them.

I. No article in The Nineteenth Century (the publication Lodge cited) bore the title he mentioned, but he was obviously referring to “On the Geographic Distribution of British Intellect,” by a young Hampshire-based physician who later abandoned medicine for a literary career: Arthur Conan Doyle.

II. Among the Primer’s rather more useful contributions to the American character: the quatrain that begins, “Now I lay me down to sleep / I pray the Lord my soul to keep.”

III. The western states in particular were incensed that New York, for instance, collected a head tax from a newly arrived laborer, but if he found his way west and into a poorhouse or a jail, he became a financial burden to the state that housed him.

IV. Adams didn’t stop on his side of the Alleghenies. He also foresaw, with equal distaste, government in the hands of “an African proletariat on the shores of the Gulf, and a Chinese proletariat in the Pacific.” And lest the third Adams brother be left out of this collection of family incantations, it’s worth quoting Brooks, the youngest, writing in the aftermath of the Panic of 1893: “Rome was a blessed garden of paradise beside the rotten, unsexed, swindling, lying Jews, represented by J. P. Morgan and the gang who have been manipulating our country for the last four years.”

V. Some sources say “Duke,” not “Dude”—but they’re wrong. See Notes, page 407.

VI. To this day the bishop’s legacy is commemorated in the Phillips Brooks House Association, a 117-year-old Harvard student organization that “strives for social justice” and counts diversity and community building among its primary goals. He is somewhat less well known as the lyricist of “O Little Town of Bethlehem.”

VII. The Irish had long been an affront to Lodge, but after he embarked on his political career, he had to temper his tempers. The people he had once characterized as “hard-drinking, idle, quarrelsome, and disorderly” now carried a terser designation—“Massachusetts voters”—and were consequently spared his invective.

VIII. Lodge and his allies always favored the term “illiteracy test,” but in later iterations (as in this book) “literacy test” became the more broadly used terminology.