15

Diet in Roman Pergamon: Preliminary results using stable isotope (C, N, S), osteoarchaeological and historical data

Abstract

Stable isotope analysis of bone collagen can offer important clues towards the reconstruction of past lives, as it provides information about past human diets, and subsistence of past populations. In this paper the living conditions of the ancient populations of Pergamon (today Prov. İzmir, Turkey) in Roman and late Byzantine times are in focus.

By the use of carbon (C) isotope ratios the amounts of C3- vs. C4-plant food and marine vs. terrestrial food can be determined. Further information on the protein sources can be achieved with the nitrogen (N) isotope value, such as the amount of animal vs. plant protein. The input of marine or freshwater food sources can be achieved with the measurements of the sulphur (S) isotope value. The results of the carbon, nitrogen and sulphur isotope analysis of the analyzed Roman and late Byzantine inhabitants of Pergamon indicate a diet based on C3-plants and terrestrial animals with no input of marine food.

In addition, results of the palaeopathological analysis of the jaws and teeth of the sampled individuals are presented. The results are discussed in the light of the medical writings by Galen from Pergamon (2nd century AD). The palaeopathological data is consistent with a plant-based diet with a remarkably high carbohydrate consumption and a certain amount of (animal) protein.

Keywords: dental diseases, diet reconstruction, Pergamon, Roman period, stable isotope analysis (C, N, S).

Introduction

The ancient city Pergamon (in Greek) or Pergamum (in Latin) is located at the northern rim of the modern city Bergama, İzmir Province (Turkey) in western Asia Minor, approximately 30 km from the Aegean Sea. The Hellenistic city is on a promontory north of the ancient river Kaikos (today Bakırçay). The hilltop with its acropolis is famous for Hellenistic architecture and art (Radt 1999). At some distance from the Hellenistic city contemporaneous monumental tumuli are located, where the rulers and other high ranked people were buried (Kelp in Otten et al. 2011).

Settlement in the lower city began mostly only in Roman times. The Roman lower city is located at the foot of the acropolis hill under the northern part of the modern city, both north and south of the river Kaikos (Radt 1999; Pirson 2011; 2014). The Roman burial grounds were mostly discovered around the ancient lower city under the modern city of Bergama (cf. Pirson 2014, 104 fig. 3).

Two burial grounds were identified on the flanks of the promontory (see Teegen, this volume, fig. 16.2). During the construction work for a cable car station in 2007 a Roman necropolis was discovered quite unexpectedly. The so-called South-East Necropolis is located just outside the city walls of Eumenes II (197–159 BC). Foundations of several funerary monuments were excavated by the German Archaeological Institute at Istanbul in close cooperation with the Museum Bergama. Around the monuments, generally containing multiple burials, several other burials were discovered, including both inhumations and some cremations. The excavations were continued in the summers of 2011 and 2013–14. In particular, one multiple burial with at least 11 individuals is worth mentioning (see Teegen, this volume, fig. 16.3).The burials are dated archaeologically to the 1st to 4th century AD (personal communication by S. Japp and U. Kelp, September 2014). Recent radiocarbon dating of human bone samples, mainly from the 2014 excavations in the South-East Necropolis revealed a calibrated time range from 40 BC to 415 AD (2 sigma probability) (GrA 62665–71, 62677–8, 63897; van der Plicht 2015).

The second cemetery was discovered in 2010 on the northern slope of the promontory (Pirson 2011). The so-called North Cemetery dates to the late Byzantine period. In 2011 eight burials were excavated (Pirson 2012).

Furthermore, human burials from two sites in the cemeteries of Elaia, the ancient port of Pergamon, were sampled (Teegen 2013, 142–3). The burials date to the Hellenistic and Roman periods (Pirson 2013, 130–1).

This paper presents the first results regarding the diet in Roman and Byzantine Pergamon. The effects of food on the body can not only be shown from a palaeopathological point of view, but also using stable isotope data. Both will be shown and discussed in this article. The combination of the elements carbon, nitrogen and sulphur will create a more detailed and accurate understanding of the dietary practices of ancient populations.

Historical accounts of Roman and Byzantine diet refer to grain as the base of the diet (Grant 2000; Teall 1959). But dry legumes and other plants must also have played an important role. Analysis of the stable carbon isotope ratios can determine the amounts of C3- vs. C4-plant food. Archaeozoological studies show that the favoured consumed terrestrial animals were sheep or goat, pig and to a lesser extent, cattle (see below). The analysis of the stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios give information about the average amount of animal food in the general diet. As mentioned above, Pergamon is situated some 30 km from the Mediterranean Sea. Archaeozoological investigations revealed fish bones and shells from the excavations in the ancient city and the South-East Necropolis (see below). Therefore, the question has to be raised whether and to which extent marine food was part of the diet. This can be addressed by analysis of the stable nitrogen and sulphur isotope ratios.

[JP, WRT]

Diet and dental diseases

Diet

Diet is fundamental to all humans and all animals as well. To study them we have a variety of approaches. The archaeological approach deals not only with vessels and other objects for storage, preparation, cooking and serving of food and drink, but also with the food and drink itself: animal bones, plant remains and burnt residues on pots are particularly important. Liquids can also leave traces in the ceramics which can be determined using e.g. gas chromatographic methods and/or stable isotope analysis (cf. Craig et al. 2011). Other sources include ancient images as well as written texts.

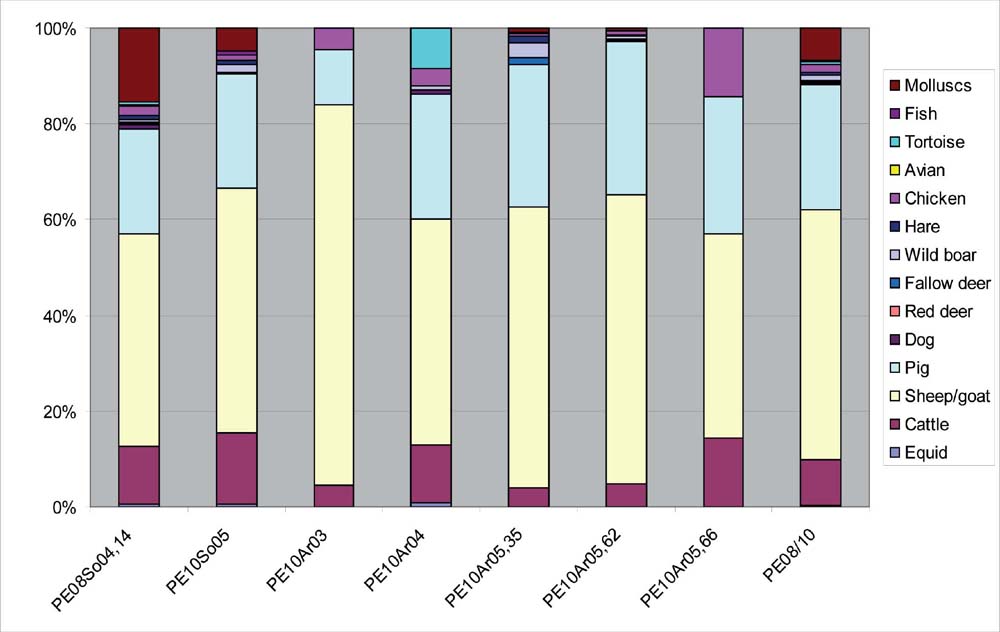

Archaeozoological analyses of animal bones from Roman and Byzantine Pergamon were carried out by the late Joachim Boessneck and Angela von den Driesch in the 1980s (Boessneck and von den Driesch 1985; von den Driesch 2008). Recently, Michael MacKinnon (2011) has published the animal bones from the eastern slope of Pergamon. All investigations have shown ovicaprines, pigs and cattle to be main sources for animal protein (Fig. 15.1). In some samples, however, other species can be of particular importance; in sample PE08-So-04-14 the frequency of molluscs is nearly 15%, in sample PE10-Ar-04 the frequency of tortoise is around 8% (cf. Fig. 15.1).

The eminent ancient physician and surgeon Galen of Pergamon (approx. 129–216/7 AD) mentioned in his book De Alimentorum Facultatibus that pig meat is the most nutritious (Grant 2000). Chicken is the most common fowl. To Galen it seemed, together with pheasant, to be the best fowl meat, for digestion and nutrition (Grant 2000). Archaeozoological investigations revealed, until now, mostly domestic fowl (Boessneck and von den Driesch 1985; von den Driesch 2008; MacKinnon 2011; personal observations by WRT).

Marine and aquatic food was also consumed. Fish bones have rarely been found. They are, however, present in small numbers (von den Driesch 2008; MacKinnon 2011; personal observations by WRT in 2012–14). In the Roman necropolis fish bones were laid on plates in grave contexts. Furthermore, in some amphora used as the burial containers for neonates, small fish bones were found upon flotation of the contents (Teegen 2015). This is an indication of the transport of fish or fish products like garum (Roman fish sauce). The species are still unidentified.

Better known are molluscs like Cardium spec., which are often found in the upper city. More difficult is their dating. Galen mentioned molluscs as being a laxative for the stomach (Grant 2000). He, however, preferred oysters. They were only sometimes found in Pergamon (personal observation by WRT).

Until now we have had no archaeobotanical data for human nutrition from Pergamon. Cisterns were discovered during the ‘Stadtgrabung’, yielding several animal bones (Boessneck and von den Driesch 1985). Samples for archaeobotany were, however, never taken nor analysed.

In this context, Galens’ treatise De Alimentorum Facultatibus, in which he also discussed food plants and their properties, is quite important. He mentioned in particular barley soup with beans as forming the daily diet for gladiators, boxers, ringers and other heavyweight athletes (Grant 2000). Barley or wheat soups are – together with bread – the most common diet for the lower classes. Beans were in Antiquity and the Middle Ages – and are still today – an important source of plant protein in the Mediterranean diet.

Fig. 15.1. Pergamon. Animal bones (N=2522) from recent excavations in the late Hellenistic and Roman city. Data from MacKinnon 2011 (Graphics: W.-R. Teegen).

As we will see shortly, the plant-based diet was common for most Roman and Byzantine Pergameneans analysed, so far, for stable isotopes.

Dental Diseases

The dental diseases present in the samples from Pergamon are dental caries, abscesses, dental calculus, parodontopathies and intra vitam tooth loss. Furthermore, teeth were probably used as tools (see Teegen, this volume, Fig. 16.7).

Dental caries (Fig. 15.2) was a common finding, mainly in the molar region. The defects could have destroyed half of the tooth crown or more. Dental caries is an infectious disease, mainly caused by Streptococcus mutans and other Streptococcaceae or other acid uric bacteria in an acidic environment (pH<7) (Schroeder 1997). The presence of carbohydrates promotes these bacteria. Indirectly, caries defects are indicators of a cariogenic diet, rich in carbohydrates.

As we have seen bread and soup (pulses) were the common daily food source for most Romans at Pergamon and elsewhere. Honey was used as a sweetener. Whether dates were eaten regularly remains an open question. They are, however, quite common in Roman sites from the eastern Mediterranean, and are mentioned by Galen as a sweet. All these sweets caused prolific dental caries, which often lead to abscesses at the tooth root and intra vitam tooth loss. This was also observed.

Another indicator of a specific diet is dental calculus. It develops mainly in a basic environment with a pH>7. It is often associated with a protein-rich diet; this view has also been discussed in the scientific literature (Lieverse 1999). Dental calculus was regularly observed in the inhumation burials from Pergamon. It is also, like today, an indicator of inadequate dental hygiene. The bacteria in the dental plaque can cause an inflammation of the gingival tissue (gingivitis) and then of the alveolar bone (Schroeder 1997; Raitapuro-Murray et al. 2014). But also the dental calculus, solidified dental plaque, can develop gingivitis. All this leads to a reduction of the alveolar rim (parodontitis) and in some cases to intra vital tooth loss.

Fig. 15.2. Pergamon, South-East Necropolis. Adult individual (PE11So11_031 #1) with parodontitis, caries and dental abscesses (Photo: W.-R. Teegen).

The kind of dental abrasion can also give some insight into diet. Meat consumers have often a special abrasion of the front teeth. Bread and pulse consumers exhibit an enlarged abrasion of the molars due to grinding (Smith 1984). Also severe abrasion of the teeth, caused, for example, by stone grind in the flour, could have led to abscesses and intra vitam tooth loss.

Analysing the teeth of the ancient Pergameneans leads to the assumption that carbohydrates were the basis of the daily diet (cf. also Wong et al., Kiesewetter, and Nováček et al., all this volume). Protein sources should have been present, but to a lesser degree. This view was supported by stable isotope analysis (see below).

In addition, the presence of numerous periodic disorders in the odontogenesis in terms of transverse linear enamel hypoplasia on the dental crowns of the individuals from the Roman and late Byzantine necropolis was found (for details see W.-R. Teegen, this volume).

[WRT]

Stable isotope analysis1

Analysis of stable carbon (δ13C), nitrogen (δ15N), and sulphur (δ34S) isotopes in bone collagen can offer important insights into the reconstruction of diet and therefore into the subsistence, but also the mobility of past populations. Isotopes are atoms of the same atomic number with the same number of protons but a different number of neutrons, thus they differ in mass.

The isotopes of nitrogen and carbon of the bone collagen reflect the origins and the amount of plant and animal proteins. In addition, sulphur isotope analysis of archaeological material can be used to answer questions related to marine versus terrestrial diets and the mobility of people. The ratio of stable carbon, nitrogen, and sulphur isotopes is expressed as the relation between the lighter and the heavier isotopes (here 13C/12C, 15N/14N, 34S/32S) of the analysed sample divided by the same isotope relation in an international standard (e.g. Nehlich 2015, 2). It is expressed in delta (δ) notation in parts per thousands (‰), for example:

The δ15N-value is a good indicator of the trophic level on which the investigated individual stands. There is a gradual enrichment, on average 3.4‰, of the heavy isotope from one trophic level to the next (Grupe et al. 2012). With that it is possible to evaluate if the person has a mainly herbivorous, omnivorous, or carnivorous diet. Herbivores show the lowest values, carnivores the highest.

By use of carbon isotope ratios the amounts of C3- vs. C4-plant food and marine vs. terrestrial food can be determined. Plants use different types of photosynthesis (C3- and C4-plants), which results in different δ13C values. C3-plants show values between –22‰ and –37‰ and C4-plants between –10‰ and –13‰ (Ambrose and Norr 1993). The δ13C-value provides information about C3- and C4-plants in the diet of humans and animals. It is also possible to distinguish terrestrial from limnic and marine habitat. In limnic biospheres the atmospheric CO2 serves as the carbon source of the plants, which leads to values between –37 and –27‰. Saltwater plants use the dissolved bicarbonate, which is about 7‰ more positive, resulting in values between –18 and –16‰ (Coltrain et al. 2004). In water habitats the δ15N-value is in general higher, the result of longer food chains.

As the δ34S value in the available food for humans ultimately depends on the δ34S values of the ecosystem, the consumption of fresh or saltwater fish can be determined (Nehlich et al. 2011).

Additionally, sulphur isotope ratios reflect the origin of food consumed during the last 10–20 years of life of an individual (Nehlich et al. 2011; Oelze et al. 2012). Plants gain most of their sulphur from the soil and the δ34S signal of the soil is derived from the local bedrock, thus collagen δ34S values of animals and humans can be used to identify the region in which an individual normally resides and therefore identify migrants (Nehlich et al. 2014; Nehlich 2015).

The combination of the δ34S data with the δ13C and δ15N values creates a more detailed and accurate understanding of the dietary practices of these populations as well as providing hitherto unknown information about migratory individuals (Nehlich 2015, 13).

Material and methods

Material

For her master’s thesis (Propstmeier 2012; 2013) at the Ludwig-Maximilian-University in Munich (Supervisor: Prof. Gisela Grupe), 70 (66 human and four animal) bone samples were analysed for stable isotopes of the elements C and N. Furthermore, the question was raised as to whether there was a marine component in their diet, since the results revealed an elevated content of stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes. Thus, the second set of further 61 human and 15 animal bones, and the 70 samples mentioned above were measured for their sulphur, carbon, and nitrogen values in the spring 2013 at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver (supervisors: Prof. M. P. Richards and Dr O. Nehlich).

Altogether 56 samples from the South-East Necropolis were analysed for stable isotopes, including three individuals from the 2007 campaign, ten individuals from single burials and 43 samples (minimum number of individuals [MNI] sampled = 10!) from the multiple burial (PE11-So11-Gr15) from the 2011 campaign.

Eight burials with 13 individuals from the North Cemetery were excavated in 2011, but only nine individuals could be sampled. For comparison, one individual from a Hellenistic monumental tumulus found in Elaia was also sampled.

In total 66 human bones and four animal bones were analysed at the Ludwig-Maximilian-University in Munich (Germany) for carbon and nitrogen isotopes.

For the sulphur, carbon, and nitrogen isotope analysis to be processed in the laboratories of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver (Canada) and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Leipzig, Germany), 76 samples (including 15 animal bones) were collected during the 2012 campaign. Sixty-nine samples were taken from the Roman South-East Necropolis at Pergamon (campaigns 2007 and 2011). The other seven samples are from Roman burials in Elaia, excavated in 2012.

Furthermore, all 70 samples studied at Munich were (re-)analysed for sulphur, carbon and nitrogen isotopes in Vancouver and Leipzig.

The total number of bone samples measured is 146. Unfortunately not all results from the two sets are available yet: only from 62 humans and 10 animals for the sulphur isotopes and 55 humans and eight animals for the carbon and nitrogen isotopes. Due to organizational reasons the carbon and nitrogen isotopes were measured separately from the sulphur isotopes. At the moment, not all datasets (C, N, S) are complete.

C- AND N-ISOTOPE ANALYSIS AT THE LUDWIG-MAXIMILIAN-UNIVERSITY

For the stable isotope analysis of the light elements carbon and nitrogen the collagen-gelatine extraction was carried out in the BioCenter of the Ludwig-Maximilian-University. 500 mg of bone powder sample was demineralized in 5 ml of 1M HCl for 20 minutes and then washed in distilled water by centrifuging at 3,000 rpm for 5 minutes.

The pellet was incubated in 5 ml of 0.125 M NaOH for 20 hours. Another washing step in distilled water followed until a pH-value of 5.5 was reached. The samples were incubated in 5 ml of 0.001M HCl (pH 3) for 10–17 hours in a hot water bath at 90°C, filtered (with a pore size of 5 μm) and lyophilized for 3–5 days at –50°C. The amount of extracted gelatine was weighed and placed in relation to the weight of the whole bone sample, which will be referred to as collagen weight proportion in per cent (weight %). Finally 0.5 mg of each sample was measured for δ13C- and δ15N-isotopes in a mass spectrometer of the type ThermoFinnigan Delta Plus.

In total, 66 human and four faunal samples of the ancient city of Pergamon were analysed for carbon and nitrogen isotopes for the master’s thesis.

C-, N-, AND S-ISOTOPE ANALYSIS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA IN VANCOUVER

Approximately a 0.5 g piece of each bone was demineralized with 0.5M HCl at 4°C for 48 hours. This step was repeated with fresh 0.5M HCl again for 48 hours. Depending on the bone sample, this step had to be repeated again until the bone was fully demineralized. After that the acid was removed from the bone samples and rinsed with purified water three times. The remaining collagen was denatured with HCl (pH3) at 75°C for 48 hours. An Ezee filter® was used to filter the sample fluid. Each sample was filled into a 30kDa Pall Microsep centrifuge filter tube and centrifuged at 4000rpm for 10 minutes. This purification process was done until the sample volume was less than 1 ml. The purified collagen had to be lyophilized for 48 hours, before measuring it in the mass spectrometer. Each sample was weighed and 4 mg put into tin capsules which were analysed on an ElementarVario Micro Cube elemental analyser coupled to an Isoprime 100 mass spectrometer (Elementar Americas Inc., New Jersey).

The second set of samples (N=146) was analysed for carbon, nitrogen, and sulphur isotopes.

Results

To use the results of the bone samples they have to fulfil certain quality criteria. Besides the weight percentage (see above), the most important criteria is the C/N ratio of 2.9 to 3.6 (van Klinken 1999), which is the result of the molar proportion of carbon to nitrogen considering the atomic mass. The amount of sulphur from archaeological bone collagen should fall into a similar range as modern bone collagen, which ranges between 0.15 and 0.35% (Nehlich and Richards 2009).

δ13C and δ15N results processed at the LMU in Munich From the first set of 70 samples 19 (28.8%) had to be excluded due to the quality criteria (C/N, weight%); six of nine late Byzantine individuals (66.6%), the only Hellenistic individual and 12 of 56 Roman samples (21.4%). In Figure 15.3 the δ13C- and δ15N-values of all the human samples are shown.

As the sample number (n=46) of the multiple burial PE11-So11-Gr15 does not represent the actual individual number, the most represented bone, the left tibia (n=7) was used to determine the minimum number of individuals. This results in a total number of individuals measured (n=20), i.e. 10 Roman individuals of single burials, 3 late Byzantine individuals, and the 7 individuals of multiple burials (Fig. 15.4).

Fig. 15.3. Pergamon, Roman South-East Necropolis and late Byzantine North Cemetery. δ13C and δ15N values (data from Propstmeier 2012) (Graphics: J. Propstmeier).

Fig. 15.4. Pergamon, Roman South-East Necropolis and late Byzantine North Cemetery. δ13C and δ15N isotope values with the mean of the four animals and the humans (n=20) (data from Propstmeier 2012) (Graphics: J. Propstmeier).

The resulting mean of the minimum number of human samples is for δ13C –18.4±0.3‰ and for δ15N 9.9±0.8‰ (Fig. 15.4). The δ13C-mean value of the herbivorous animals is –19.3±0.6‰ and the δ15N-mean is 6.8±0.1‰. The carnivorous dog lies in between the omnivorous humans and the herbivorous animals with a δ15N-value of 8.2‰ and a δ13C-value of –18.8‰. This indicates a diet based on C3-plants and C3-plant-consuming terrestrial animals with some individuals having higher δ15N-values.

[JP, GG]

δ34S, δ13C and δ15N results processed at the UBC in Vancouver

Only half of the samples (n=72/146) have so far been measured for sulphur. The human and animal samples that were measured fulfil the quality criteria for the δ34S-values (%S), as they range from 0.2–0.3% (Nehlich and Richards 2009). The herbivorous animals (n=8, cattle, pig, equid, and sheep) have a mean δ34S-value of 6.8±1.1‰, the ratios range from 5.1‰ (cattle) to 8.3‰ (cattle). The median of the herbivorous is 6.8‰. The two carnivorous dogs show δ34S-values of 6.2‰ and 7.1‰ with a mean of 6.7±0.4‰ (Fig. 15.5).

Sulphur isotope values of all humans analysed so far (n=62) range from 2.6‰ to 14.5‰ with a mean of 6.9±2.0‰ and a median of 6.8‰ (Fig. 15.5).

As mentioned above, not only sulphur isotope, but also carbon and nitrogen isotope values were determined. As seven of the human samples have not fulfilled the quality criteria (C/N, weight%), only 55 samples were used for interpretation. The δ15N- and δ13C-values of the humans have a mean value for nitrogen of 9.9±0.9‰ and for carbon of –18.9 ±0.6‰. The herbivores (n=6) have a mean δ15N of 5.2±0.9‰ and δ13C of –20.1±0.7‰ (Fig. 15.6).

The two dogs show δ15N- and δ13C-values of 7.8±0.7‰ and –18.9±0.4‰ respectively, ranging in between the herbivores and the humans (Fig. 15.6).

[JP, ON, MPR]

Interpretation

δ13C- and δ15N-values processed at the LMU in Munich

The herbivores, sheep and cattle show δ13C- and δ15N-values that indicate a diet based on C3-plants. The δ15N-value of the pig is, with 6.6‰, even lower than the herbivores and refers to a plant-based diet. Meat was probably too valuable to feed to pigs or to throw away. The mainly carnivorous dog has a δ15N-value of 8.2‰ and falls in between the herbivorous animals and the omnivorous humans; indicating again, that meat was probably rare and was not fed to animals like dogs and pigs.

Fig. 15.5. Pergamon, Roman South-East Necropolis and late Byzantine North Cemetery. δ15N and δ34S isotope values for humans, herbivorous and carnivorous animals (Graphics: J. Propstmeier).

The mean value of the humans is –18.4±0.3‰ for δ13C and 9.9±0.8‰ for δ15N showing a diet based on C3-plants and C3-plant-consuming animals. There is a significant positive correlation between the N- and the C- isotopes (Pearson 0.629, p<0.01) of the humans. Marine input increases both the C- and the N-values, which could indicate a marine input in some of the individuals of Pergamon. In several publications a positive correlation between the δ13C- and δ15N-values were explained by a marine input and to some extent proven by an oligo element analysis (Giorgi et al. 2005). Freshwater fish were probably not consumed. Eating freshwater fish could result in more negative δ13C-values. As Vika and Theodoropoulou (2012) have recently shown for the Eastern Mediterranean, freshwater and marine fish are often indistinguishable in their δ13C- and δ15N-values.

The δ15N-value of the above-mentioned faunal species lies in the average range of 6.8‰. Humans, which have consumed these animals, must have values, if one assumes a fractionation factor of 3‰, higher than 9.8‰. All samples having lower values must have had a mainly herbivorous diet (Fig. 15.7, in green). One individual even has nitrogen values lower than the dog. Reasons for this could be a different population stratum or that this person lived in a different time; so warlike conflicts, bad harvests, or epidemics could have occurred and some individuals may have temporarily suffered from an insufficient food supply.

The humans who have higher values than 9.8‰ had a mixed diet of plants and animals (Fig. 15.7, in blue). Some individuals even have much higher nitrogen values than the standard deviation of the mean value (Fig. 15.4). This seems to indicate a marine input in their diet; they have higher C-values as well (Fig. 15.7, in red). The sulphur isotope analysis could, however, not confirm this result (see below).

Summarizing the results, the diet of the investigated individuals was based on C3-plants such as grain and vegetables like beans, as well as C3-plant-consuming terrestrial animals. These findings are supported by the results of the archaeozoological investigation and the dental diseases found in the cemeteries studied (see above).

[JP, GG]

Fig. 15.6. Pergamon, Roman South-East Necropolis and late Byzantine North Cemetery. δ13C and δ15N values for humans, herbivorous and carnivorous animals (Graphics: J. Propstmeier).

The early Byzantine warrior

In 2006 an exceptional early Byzantine burial of a young male individual and several grave goods (including weapons) was discovered in Pergamon (Otten et al. 2011). Stable isotope analysis of the elements nitrogen, carbon, strontium, and oxygen was carried out by G. Müldner, J. Evans, and A. Lamb (in Otten et al. 2011) at the University of Reading. For comparison the skeletons of a Roman adult male and a late Byzantine child were analysed as well (see Fig. 15.8).

Both of the last mentioned individuals showed similar δ13C- and δ15N-values to the individuals analysed in Munich. But the early Byzantine male had an elevated δ13C values in contrast to the other individuals which indicates a diet with different plants (C4-plants). To our present knowledge, C4-food plants were not or only rarely used in Pergamon. For the early Byzantine warrior a different origin can be assumed (Fig. 15.3), where C4-plants played a more major role in the daily diet. A precise point of origin could not be determined by the results of the strontium and oxygen stable isotope analysis as the data were consistent with the wider East Mediterranean area (Müldner et al. in Otten et al. 2011).

[GHM]

δ34S-, δ15N- and δ13C-values processed at the UBC in Vancouver

Preliminary results of the sulphur, carbon, and nitrogen isotope analysis of humans and animals of Pergamon will be presented here. As mentioned above, not all results for the 146 samples studied were available yet for presentation (for sulphur: humans n=62, animals n=10; for carbon and nitrogen: human n=55, animals n=8).

The δ34S-values of the herbivores (n=8) have a rather small range (5.2‰ to 8.3‰) with a mean of 6.8±1.1‰. As the trophic level shift of sulphur isotope ratios between diet and consumers’ tissue is low, around –1.0‰, the δ34S range of the humans can be expected to be in the δ34S range of the animals. Humans with solely terrestrial-based diets would have δ34S-values within the range of the δ34S-values of the terrestrial animals (or within 1‰, due to the small fractionation effect). The δ34S range of the humans is 2.6‰ to 14.5‰ with a mean of 6.9±2.0‰ and fall into the range of terrestrial animals, representing the local variety and dietary variability. This suggests that the main dietary resource consisted of terrestrial domesticated animals; there is no indication of a marine input. But there are also a few humans that do not fall into this range (Fig. 15.5). It can be concluded that either the investigated animals do not represent the full range of biologically available δ34S values or some individuals migrated to Pergamon. A marine input can also be excluded; in this case, higher δ13C-values would be expected.

Fig. 15.7. Pergamon, Roman South-East Necropolis and late Byzantine North Cemetery. δ13C and δ15N values of humans and animals. Green: mostly herbivorous diet, blue: omnivorous diet, red: probable marine input (Graphics: J. Propstmeier).

The two mainly carnivorous dogs show values that are also placed within the range of the terrestrial animals.

The herbivores (n=6) show a δ13C-mean value of –20.1±0.6‰ and a slightly lower δ15N value of 5.2±0.8‰ than the herbivorous animals analysed in the first set at the LMU in Munich. The two dogs have a δ15N mean value of 7.8±0.6‰ and a δ13C mean value of –18.9±0.4‰. This places the dogs again in between the herbivores and the humans.

The δ15N and δ13C mean values of the humans of the second dataset are quite similar to the mean values of the samples of the first dataset. Most of the human values (mean value of 9.9±0.9‰ for δ15N and –18.9±0.5‰ for δ13C) fall within the standard deviation of the mean (Fig. 15.6). This again indicates a diet based on C3-plants and C3-plant-consuming animals.

Two individuals from the Roman necropolis show very low carbon values, the lowest one is a child between 7 and 12 years of age. Another individual shows very high carbon values, indicating a diet based on C4-plants, like the above-mentioned early Byzantine warrior (Otten et al. 2011). It has very low nitrogen values, indicating that this person had a mainly herbivorous diet (Fig. 15.7), as he/she is in the same range as the herbivorous animals. It cannot be excluded, that these outliers come from a different place of origin with different food traditions. Again the δ34S values for these individuals are not yet available for interpretation.

These outliers should be studied more in detail. Bad harvests have to be taken into consideration; such events were described by Galen for the 2nd century AD. In general, the alimentary status of the individuals investigated was not bad. As described by Teegen (this volume), enamel hypoplasias are quite common in Pergamon, both in the Roman and Byzantine period. Severe forms are very rare. At the moment, there are no indications of severe malnourishment. It seems more likely that the enamel defects were mainly caused by diseases in childhood.

It was surprising that there was not a significant amount of marine food consumption by individuals at this site close to the Mediterranean Sea.

Fig. 15.8. Pergamon. δ13C and δ15N values of the Roman South-East Necropolis and the late Byzantine North Cemetery in comparison to the Early Byzantine warrior burial (PE06-Sy01) a Late Byzantine child burial (PE07-So19-004) and the Roman adult (PE07-So04-001) (data from Müldner in Otten et al. 2011) (Graphics: J. Propstmeier).

As there are still samples to evaluate, they will help to gain an even better and broader insight into the diet and the living conditions of the populations of Pergamon.

[JP, ON, MPR]

Conclusion

The results of the carbon, nitrogen, and sulphur isotope analysis of the Roman and late Byzantine skeletons from Pergamon indicate a diet based on C3-plants and terrestrial animals with no input of marine food. Similar observations were made for Sagalassos (Fuller et al. 2012), one of the few sites from Asia Minor where analyses of stable isotopes for diet reconstruction were carried out (for other new investigations see the relevant contributions in this volume). This is in accordance with the archaeozoological investigations at Pergamon, where only rarely fish bones were observed (Boessneck and von den Driesch 1985; von den Driesch 2008; MacKinnon 2011; personal observations by WRT during the 2012–14 campaigns). The same can be assumed for the Byzantine period (cf. Kroll 2010; 2012). The sometimes quite high amount of molluscs (cf. Fig. 15.1), which can also be observed in Byzantine contexts (personal observations by WRT in Priene and Pergamon), probably left no, or only slight, traces in the isotopic values. This needs, however, further investigation.

The palaeopathological study of the jaws and teeth indicates a more plant-based diet with a remarkably high carbohydrate consumption and a certain amount of (animal) protein. The present study underlines the importance of sulphur isotope analysis for the investigation of possible marine food intake.

[WRT, JP]

Note

The stable isotope analyses were part of the project ‘Anthropological and palaeopathological investigations in the Roman South-East Necropolis of Pergamon’ (head W.-R. Teegen) in the framework of two projects ‘The Roman South-East Necropolis of Pergamon’, supported by the Gerda Henkel Foundation 2011–14 (principal investigator F. Pirson). All raw data will be published in the final publication of the South-East Necropolis, to be edited by U. Kelp and W.-R. Teegen.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Pergamon excavation of the German Archaeological Institute (director Professor Felix Pirson), the Gerda Henkel-Foundation and the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) for support. The Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism (Ankara) kindly granted all necessary permits. We are further grateful to the anonymous reviewer for helpful comments.

Bibliography

Ambrose, S. and Norr, L. (1993) Experimental evidence for the relationship of the carbon isotope ratios of whole diet and dietary protein to those of bone collagen and carbonate. In J. Lambert and G. Grupe (eds.) Prehistoric human bone: Archaeology at the molecular level, 1–37. Berlin, Heidelberg, and New York, Springer.

Boessneck, J. and von den Driesch, A. (1985) Knochenfunde aus Zisternen in Pergamon. Munich, Institut für Paläoanatomie, Domestikationsforschung und Geschichte der Tiermedizin der Universität München.

Coltrain, J., Harris, J., Cerling, T., Ehleringer, J., Dearing, M., Ward, J., and Allen, J. (2004) Rancho La Brea stable isotope biogeochemistry and its implications for the palaeoecology of Late Pleistocene, coastal southern California. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 205, 199–219.

Craig, O. E., Steele, V. J., Fischer, A., Hartz, S., Andersen, S. H., Donohoe, P., Glykou, A., Saul, H., Jones, D. M., Koch, E., and Heron, C. P. (2011) Ancient lipids reveal continuity in culinary practices across the transition to agriculture in Northern Europe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 17910–5.

Driesch, A. von den (2008) Tierreste aus dem Podiensaal. In H. Schwarzer, Das Gebäude mit dem Podiensaal in der Stadtgrabung von Pergamon. Studien zu sakralen Banketträumen mit Liegepodien in der Antike (Die Stadtgrabung. Teil 4. Altertümer von Pergamon XV.4), 309–13. Berlin and New York, de Gruyter.

Fuller, B. T., Cupere, B., de Marinova, E., Van Neer, W., Waelkens, M., and Richards, M. P. (2012) Isotopic reconstruction of human diet and animal husbandry practices during the Classical-Hellenistic, Imperial, and Byzantine periods at Sagalassos, Turkey. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 149.2, 157–71.

Giorgi, F., Bartoli, F., Iacumin, P., and Mallegni, F. (2005) Oligoelements and isotopic geochemistry: A multidisciplinary approach to the reconstruction of the palaeodiet. Human Evolution 20, 55–82.

Grant, M. (2000) Galen on food and diet. London and New York, Routledge.

Grupe, G., Christiansen, K., Schröder, I., and Wittwer-Backofen, U. (2012) Anthropologie. Ein einführendes Lehrbuch (2nd ed.). Berlin, Heidelberg, and New York, Springer.

Kiesewetter, H. (this volume), Toothache, back pain, and fatal injuries: What skeletons reveal about life and death at Roman and Byzantine Hierapolis, 268–85.

Klinken, G. J. van (1999) Bone collagen quality indicators for palaeodietary and radiocarbon measurements. Journal of Archaeological Science 26, 687–95.

Kroll, H. (2010) Tiere im Byzantinischen Reich. Archäozoologische Forschungen im Überblick (Monographien des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums 87). Mainz, Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum.

Kroll, H. (2012) Animals in the Byzantine Empire: An overview of the archaeozoological evidence. Archeologia Medievale 39, 93–121.

Lieverse, A. R. (1999) Diet and the aetiology of dental calculus. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 9, 219–32.

MacKinnon, M. R. (2011) Animal use at Hellenistic Pergamon: Evidence from zooarchaeological analyses. Archäologischer Anzeiger 2011.2, 193–8.

Nehlich, O., and Richards, M. P. (2009) Establishing collagen quality criteria for sulphur isotope analysis of archaeological bone collagen. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 1.1, 59–75.

Nehlich, O. (2015) The application of sulphur isotope analyses in archaeological research: A review. Earth-Science Reviews 142, 1–17.

Nehlich, O., Fuller, B., Jay, M., Mora, A., Nicholson, R., Smith, C., and Richards, M. P. (2011) Application of sulphur isotope ratios to examine weaning patterns and freshwater fish consumption in Roman Oxfordshire, UK. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 75, 4963–7.

Nehlich, O., Oelze, V., Jay, M., Conrad, M., Stäuble, H., Teegen, W.-R., and Richards, M. P. (2014) Sulphur isotope ratios of multi-period archaeological skeletal remains from central Germany: A dietary and mobility study. Anthropologie (Brno) 52, 15–33.

Nováček, J., Scheelen, K., and Schultz, M. (this volume) The wrestler from Ephesus: Osteobiography of a man from the Roman period based on his anthropological and palaeopathological record, 318–38.

Oelze, V., Koch, J., Kupke, K., Nehlich, O., Zäuner, S., Wahl, J., Weise, S., Rieckhoff, S., and Richards, M. P. (2012) Multi-isotopic analysis reveals individual mobility and diet at the Early Iron Age monumental tumulus of Magdalenenberg, Germany. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 148, 406–21.

Otten, T., Evans, J., Lamb, A., Müldner, G., Pirson, A., and Teegen, W.-R. (2011) Ein frühbyzantinisches Waffengrab aus Pergamon. Interpretationsmöglichkeiten aus archäologischer und naturwissenschaftlicher Sicht. Istanbuler Mitteilungen 61, 347–422.

Pirson, F. (2011) Pergamon – Bericht über die Arbeiten in der Kampagne 2010. Archäologischer Anzeiger 2011.2, 81–212.

Pirson, F. (2012) Pergamon – Bericht über die Arbeiten in der Kampagne 2011. Archäologischer Anzeiger 2012.2, 175–274.

Pirson, F. (2013) Pergamon – Bericht über die Arbeiten in der Kampagne 2012. Archäologischer Anzeiger 2013.2, 79–164.

Pirson, F. (2014) Pergamon – Bericht über die Arbeiten in der Kampagne 2013. Archäologischer Anzeiger 2014.2, 101–76.

Plicht, J. van der (2015) Unpublished Reports CIO/433-2015/PWL and CIO/582-2015/PWL. 07.04.2015 and 21.09.2015.

Propstmeier, J. (2012) Die Lebensbedingungen in Pergamon: Nahrungsrekonstruktion mit Hilfe stabiler Stickstoff- und Kohlenstoffisotope einer römischen und spätbyzantinischen Nekropole. Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Munich.

Propstmeier, J. (2013) Analyse stabiler Isotope zur Ernährungsrekonstruktion. Archäologischer Anzeiger 2013.2, 141–42.

Radt, W. (1999) Pergamon. Geschichte und Bauten einer antiken Metropole. Darmstadt, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Raitapuro-Murray, T., Molleson, T. I., and Hughes, F. J. (2014) The prevalence of periodontal disease in a Romano-British population c. 200–400 AD. British Dental Journal 217.8, 459–66.

Schroeder, H. E. (1997) Pathobiologie oraler Strukturen, 3rd ed. Basel, Karger.

Smith, B. H. (1984) Patterns of molar wear in hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 63, 39–56.

Teall, J. L. (1959) The grain supply of the Byzantine Empire, 330–1025. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 13, 87–139.

Teegen, W.-R. (2013) Die anthropologisch-paläopathologischen Untersuchungen 2012. Archäologischer Anzeiger 2013.2, 138–43.

Teegen, W.-R. (2015) Die anthropologisch-paläopathologischen Untersuchungen in Pergamon 2014. Archäologischer Anzeiger 2015.2, 158–63.

Teegen, W.-R. (this volume) Pergamon – Kyme – Priene: Health and disease from the Roman to the late Byzantine period in different locations of Asia Minor, 250–67.

Vika, E., and Theodoropoulou, T. (2012) Re-investigating fish consumption in Greek antiquity: Results from δ 13 C and δ 15 N analysis from fish bone collagen. Journal of Archaeological Science 39.5, 1618–27.

Wong, M., Nauman, E., Jaouen, K., and Richard, M. (this volume) Isotopic investigations of human diet and mobility at the site of Hierapolis, Turkey, 228–36.