Chapter 4

Migration Patterns

To understand where your ancestors came from, it is necessary to study the migration patterns in the region or the state where your ancestors lived. The movements can be traced of slave owners who moved from one state to another. They often did not move alone, but carried with them their families, extended family, and property. When they bought large tracts of land in Alabama and relocated, they either brought slaves with them or purchased additional slaves to work and clear the land. Tommy Rogers states that “45 percent of the 420,000 native-born, free persons who were living in Alabama at the time of the census of 1850 had moved into Alabama from other states.” He goes on to say that five states—Georgia, Carolinas, Tennessee and Virginia—accounted for 40 percent of Alabama’s free population.[6] In Black Genesis, James Rose and Alice Eichholz provide an additional theory as to how the slave population in Alabama was supplied when they state that “the largest coast cargoes of slaves were shipped from Alexandria, Norfolk, and Richmond, Virginia; Baltimore, Maryland; or Charleston, South Carolina, to the ports of Natchez [Mississippi], Mobile, Alabama, and New Orleans, Louisiana, where they were sold inland.”

This chapter is not meant to be an in-depth study of the migration patterns of Alabama’s settlers, but rather an overview for the reader to continue their research on the movements of their particular family. The references at the end of this chapter will help in further studying.

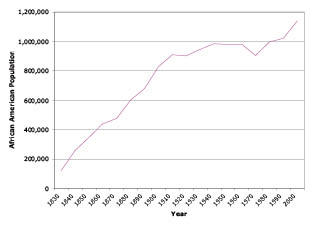

As the chart on this page indicates, the free black and slave population from 1830 to 1860 shows an increase, and the overall black population continues to increase after slavery. The difference is location—from rural to urban. “In the years from 1890 to the early 1900s, although blacks continued to trickle from South to North and West, migration seems to have been greater from county to town within individual regions” (Florette Henri, Black Migration: Movement North, 1900–1920). “In 1870 over 90 percent of the United States Negro population lived in the South; by 1960, less than 60 percent lived there” (Daniel O. Price, Changing Characteristics of the Negro Population). According to the below chart, the black population in Alabama did not have a significant decrease until the 1970s, but started to increase again in the 1980s. This one fact will help in locating your Alabama African American ancestors, because they tended to stay in Alabama, which means that they created some type of record. We just have to use our imagination to locate their records. The county sections in this book will help you to explore some of these records.

African American population in Alabama by year.

According to Ulrich B. Phillips, in his book, Plantation and Frontier Documents, a visitor in Georgia reported “hordes of cotton planters from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, with large gangs of Negroes bound for Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana ‘where the cotton land is not worn out.’” Phillips, along with others who have studied the migration patterns of people coming into the Southern states, all agree that one of the main reasons for settling in these states was “the upper South’s soil depletion and erosion.”

Some of the sources listed in this chapter, along with the resources listed below, can be used as the basis for researching the migratory patterns of Alabama African Americans population.

Resources

Bancroft, Frederick. Slave Trading in the Old South. Baltimore: J. H. Furst Co., 1931.

Drago, Edmund L., ed. Broke by the War: Letters of a Slave Trader in the Old South. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

Free Negro Heads of Families in the United States in 1830. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, 1925.

Grossman, James R. Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Guttman, Herbert. The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750–1925. New York: Pantheon, 1976.

Kennedy, Louise Venable. The Negro Peasant Turns Cityward: Effects of Recent Migrations to Northern Centers. New York: Columbia University Press, 1930.

“Negro Migration to the North,” Current History. 20 (Sept., 1924).

Rogers, William W. “The Negro Alliance in Alabama.” Journal of Negro History, 45 (January, 1960).

Tadman, Michael. Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

United States Department of Labor, Division of Negro Economics. Negro Migration in 1916–1917. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1919.

Wiley, Bell I., Southern Negro, 1861–1865. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1938.

Woodson, Carter G. A Century of Negro Migration. New York: Russell & Russell, 1969.

[6] Rogers, Tommy W. “Migration Patterns of Alabama’s Population, 1850 and 1860.” Alabama Historical Quarterly. 28.1–2: 45–50.