Welcome to American Accent Training. This book and audio is designed to get you started on your American accent. We’ll follow the book and go through the 17 lessons and all the exercises step by step. Everything is explained, and hyperlinks to the Answers have been provided, wherever applicable.

WHAT IS ACCENT?

Accent is a combination of four main components: voice quality, intonation (speech music), liaisons (word connections), and pronunciation (the spoken sounds of vowels, consonants, and combinations). As you go along, you’ll notice that you’re being asked to look at accent in a different way. You’ll also realize that the grammar you studied before and this accent you’re studying now are completely different.

Part of the difference is that grammar and vocabulary are systematic and structured—the letter of the language. Accent, on the other hand, is free form, intuitive, and creative—more the spirit of the language. So, thinking of music, feeling, and flow, let your mouth relax into the American accent.

CAN I LEARN A NEW ACCENT?

Can a person actually learn a new accent? Many people feel that after a certain age, it’s just not possible. Can classical musicians play jazz? If they practice, of course they can! For your American accent, it’s just a matter of learning and practicing techniques this book will teach you. It is up to you to use them or not. How well you do depends mainly on how open and willing you are to sounding different from the way you have sounded all your life.

A very important thing you need to remember is that you can use your accent to say what you mean and how you mean it. Word stress conveys meaning through tone or feeling, which can be much more important than the actual words that you use. We’ll cover the expression of these feelings through intonation in the first lesson.

You may have noticed that I talk fast and often run my words together. You’ve probably heard enough “English-teacher English” where . . . everything . . . is . . . pronounced without having to listen too carefully. We’re going to talk just like the native speakers that we are, in a normal conversational tone.

Native speakers often tell people who are learning English to “slow down” and to “speak clearly.” This is meant with the best of intentions, but it is exactly the opposite of what a student really needs to do. If you speak fairly quickly, with strong intonation and good voice quality, you will be understood more easily. To illustrate this point, you will hear a Chinese gentleman first trying to speak slowly and carefully and then repeating the same two sentences quickly and with clear intonation. The difference makes him sound like a completely different person.

Please listen. You will hear the same words twice.

Please listen. You will hear the same words twice.

Hello, my name is Raymond Choon.

You may have to listen a couple of times to catch everything. To help you, every word is also written in the book. By seeing and hearing simultaneously, you’ll learn to reconcile the differences between the appearance of English (spelling) and the sound of English (pronunciation and the other aspects of accent).

The audio leaves a rather short pause for you to repeat into. The point of this is to get you responding quickly and without spending too much time thinking about your response.

ACCENT VERSUS PRONUNCIATION

Many people equate accent with pronunciation. I don’t feel this to be true at all. America is a big country, and while the pronunciation varies from the East Coast to the West Coast, from the southern to the northern states, two components that are uniquely American stay basically the same—the speech music, or intonation, and the word connections, or liaisons. Throughout this program, we will focus on them. In the latter part of the book we will work on pronunciation concepts, such as Cat? Caught? Cut? and Betty Bought a Bit of Better Butter; we also will work our way through some of the difficult sounds, such as TH, the American R, the L, V, and Z.

“WHICH ACCENT IS CORRECT?”

American Accent Training was created to help people “sound American” for lectures, interviews, teaching, business situations, and general daily communication. Although America has many regional pronunciation differences, the accent you will learn is that of standard American English as spoken and understood by the majority of educated native speakers in the United States. Don’t worry that you will sound slangy or too casual, because you most definitely won’t. This is the way a professor lectures to a class, the way a national newscaster broadcasts, the way that is most comfortable and familiar to the majority of native speakers.

“WHY IS MY ACCENT SO BAD?”

Learners can be seriously hampered by a negative outlook, so I’ll address this very important point early. First, your accent is not bad; it is nonstandard to the American ear. There is a joke that goes: What do you call a person who can speak three languages? Trilingual. What do you call a person who can speak two languages? Bilingual. What do you call a person who can only speak one language? American.

Every language is equally valid or good, so every accent is good. The average American, however, truly does have a hard time understanding a nonstandard accent. George Bernard Shaw said that the English and Americans are two people divided by the same language!

Some students learn to overpronounce English because they naturally want to say the word as it is written. Too often an English teacher may allow this, perhaps thinking that colloquial American English is unsophisticated, unrefined, or even incorrect. Not so at all! Just as you don’t say the T in listen, the TT in better is pronounced D, bedder. Any other pronunciation will sound foreign, strange, wrong, or different to a native speaker.

LESS THAN IT APPEARS . . . MORE THAN IT APPEARS

As you will see in the “Squeezed-Out Syllables” section, some words appear to have three or more syllables, but all of them are not actually spoken. For example, business is not (bi•zi•ness), but rather (biz•ness).

Just when you get used to eliminating whole syllables from words, you’re going to come across other words that look as if they have only one syllable, but really need to be said with as many as three! In addition, the inserted syllables are filled with letters that are not in the written word. I’ll give you two examples of this strange phenomenon. Pool looks like a nice, one-syllable word, but if you say it this way, at best, it will sound like pull, and at worst will be unintelligible to your listener. For clear comprehension, you need to say three syllables (pu/wuh/luh). Where did that W come from? It’s certainly not written down anywhere, but it is there just as definitely as the P is there. The second example is a word like feel. If you say just the letters that you see, it will sound more like fill. You need to say (fee/yuh/luh). Is that really a Y? Yes. These mysterious semivowels are explained under Liaisons. They can appear either inside a word, as you have seen, or between words, as you will learn.

LANGUAGE IS FLUENT AND FLUID

Just like your own language, conversational English has a very smooth, fluid sound. Imagine that you are walking along a dry riverbed with your eyes closed. Every time you come to a rock, you trip over it, stop, continue, and trip over the next rock. This is how the average foreigner speaks English. It is slow, awkward, and even painful. Now imagine that you are a great river rushing through that same riverbed—rocks are no problem, are they? You just slide over and around them without ever breaking your smooth flow. It is this feeling that I want you to capture in English.

Changing your old speech habits is very similar to changing from a stick shift to an automatic transmission. Yes, you continue to reach for the gearshift for a while, and your foot still tries to find the clutch pedal, but this soon phases itself out. In the same way, you may still say “telephone call” (kohl) instead of (kahl) for a while, but this too will soon pass.

You will also have to think about your speech more than you do now. In the same way that you were very aware and self-conscious when you first learned to drive, you will eventually relax and deal with the various components simultaneously.

A new accent is an adventure. Be bold! Exaggerate wildly! You may worry that Americans will laugh at you for putting on an accent, but I guarantee you, they won’t even notice. They’ll just think that you’ve finally learned to “talk right.” Good luck with your new accent!

A FEW WORDS ON PRONUNCIATION

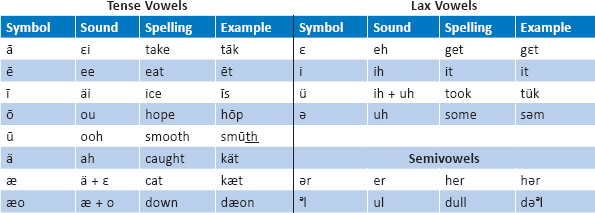

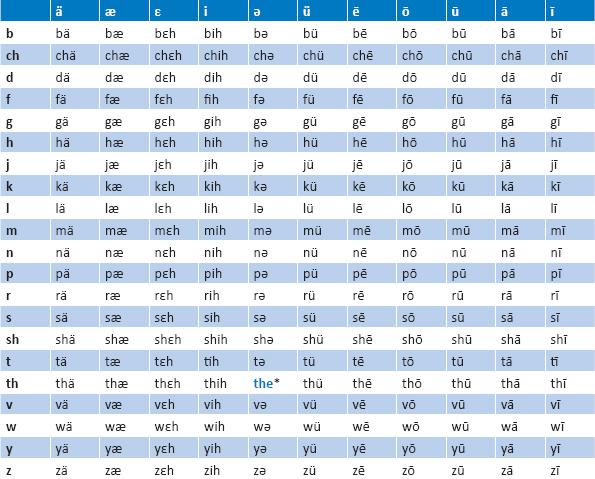

I’d like to introduce you to the pronunciation guide outlines in the following chart. There aren’t too many characters that are different from the standard alphabet, but just so you’ll be familiar with them, look at the chart. It shows eight tense vowels and six lax vowels and semivowels.

Tense Vowels? Lax Vowels?

In some books, tense vowels are called long and lax vowels are called short. Since you will be learning how to lengthen vowels when they come before a voiced consonant, it would be confusing to say that hen has a long, short vowel. It is more descriptive to say that it has a lax vowel that is doubled or lengthened.

Although this may look like a lot of characters to learn, there are really only four new ones: æ, ä,  , and ü. Under Tense Vowels, you’ll notice that the vowels that say their own name simply have a line over them: ā, ē, ī, ō, ū. There are three other tense vowels. First, ä is pronounced like the sound you make when the doctor wants to see your throat, or when you loosen a tight belt and sit down in a soft chair—aaaaaaaah! Next, you’ll find æ, a combination of the tense vowel ä and the lax vowel ε. It is similar to the noise that a goat or a lamb makes (half, last, chance). The last one is æo, a combination of æ and o. This is a very common sound, usually written as ow or ou in words like down or round.

, and ü. Under Tense Vowels, you’ll notice that the vowels that say their own name simply have a line over them: ā, ē, ī, ō, ū. There are three other tense vowels. First, ä is pronounced like the sound you make when the doctor wants to see your throat, or when you loosen a tight belt and sit down in a soft chair—aaaaaaaah! Next, you’ll find æ, a combination of the tense vowel ä and the lax vowel ε. It is similar to the noise that a goat or a lamb makes (half, last, chance). The last one is æo, a combination of æ and o. This is a very common sound, usually written as ow or ou in words like down or round.

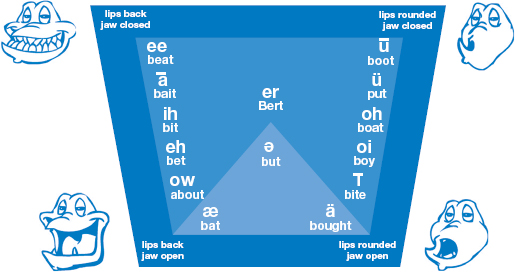

A tense vowel requires you to use a lot of facial muscles to produce it. If you say ē, you must stretch your lips back; for ū you must round your lips forward; for ä you drop your jaw down; for æ you will drop your jaw far down and back; for ā bring your lips back and drop your jaw a bit; for ī drop your jaw for the ah part of the sound and pull it back up for the ee part; and for ō round the lips, drop the jaw, and pull back up into ū. An American ō is really ōū.

Now you try it. Repeat after me. ē, ū, ā, æ, ä, ī, ō.

Now you try it. Repeat after me. ē, ū, ā, æ, ä, ī, ō.

A lax vowel, on the other hand, is very reduced. In fact, you don’t need to move your face at all. You only need to move the back of your tongue and your throat. These sounds are very different from most other languages.

Under Lax Vowels, there are four reduced vowel sounds, starting with the Greek letter epsilon ε, pronounced eh; i pronounced ih, and ü pronounced ü, which is a combination of ih and uh, and the schwa,  , pronounced uh—the softest, most reduced, most relaxed sound that we can produce. It is also the most common sound in English. The semivowels are the American R (pronounced er, which is the schwa plus R) and the American L (which is the schwa plus L).

, pronounced uh—the softest, most reduced, most relaxed sound that we can produce. It is also the most common sound in English. The semivowels are the American R (pronounced er, which is the schwa plus R) and the American L (which is the schwa plus L).

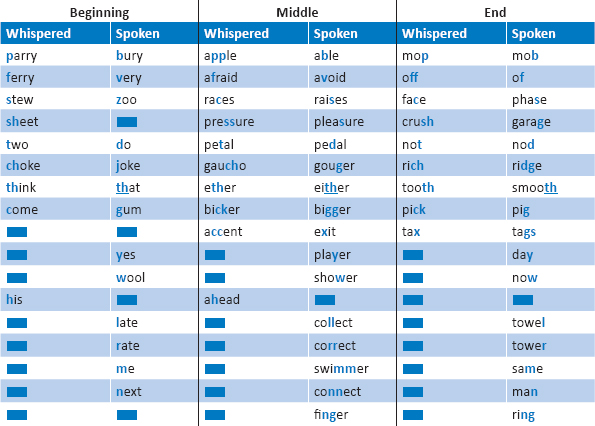

Voiced Consonants? Unvoiced Consonants?

A consonant is a sound that causes two points of your mouth to come into contact, in three locations—the lips, the tip of the tongue, and the throat. A consonant can either be unvoiced (whispered) or voiced (spoken), and it can appear at the beginning, middle, or end of a word. You’ll notice that for some categories, a particular sound doesn’t exist in English.

Pronunciation Points

In many dictionaries, you may find a character that looks like an upside-down V (Λ) and another character that is an upside-down e ( ), the schwa. There is a linguistic distinction between the two, but they are pronounced exactly the same. Since you can’t hear the difference between these two sounds, we’ll just be using the upside-down e to indicate the schwa sound. It is pronounced uh.

), the schwa. There is a linguistic distinction between the two, but they are pronounced exactly the same. Since you can’t hear the difference between these two sounds, we’ll just be using the upside-down e to indicate the schwa sound. It is pronounced uh.

The second point is that we do not differentiate between ä and  . The ä is pronounced ah. The backwards C (

. The ä is pronounced ah. The backwards C ( ) is more or less pronounced aw. This aw sound has a “back East” sound to it, and as it’s not common to the entire United States, it won’t be included here.

) is more or less pronounced aw. This aw sound has a “back East” sound to it, and as it’s not common to the entire United States, it won’t be included here.

R can be considered a semivowel. One characteristic of a vowel is that nothing in the mouth touches anything else. R definitely falls into that category. So in the exercises throughout the book it will be treated not so much as a consonant, but as a vowel.

The ow sound is usually indicated by äu, which would be ah + ooh. This may have been accurate at some point in some locations, but the sound is now generally æo. Town is tæon, how is hæo, loud is læod, and so on.

Besides voiced and unvoiced, there are two words that come up in pronunciation. These are sibilant and plosive. When you say the s sound, you can feel the air sliding out over the tip of your tongue—this is a sibilant. When you say the p sound, you can feel the air popping out from between your lips—this is a plosive. Be aware that there are two sounds that are sometimes mistakenly taught as sibilants, but are actually plosives: th and v.

For particular points of pronunciation that pertain to your own language, click here to refer to the Nationality Guides.

WE DON’T HAVE SOME OF THOSE SOUNDS IN MY LANGUAGE . . .

This is undoubtedly true, but you can see that you only need to pick up a limited number of new sounds (ä, æ, ε,  , ü). Given what you’ve already accomplished in life, this is not a big deal. A Chinese speaker was once bemoaning how hard it was for him to say the R. When asked if he went to college, he said “Of course, I have a PhD in physics from Caltech.” After a beat, he realized that compared to that . . . the R is not harrrrrrrrd.

, ü). Given what you’ve already accomplished in life, this is not a big deal. A Chinese speaker was once bemoaning how hard it was for him to say the R. When asked if he went to college, he said “Of course, I have a PhD in physics from Caltech.” After a beat, he realized that compared to that . . . the R is not harrrrrrrrd.

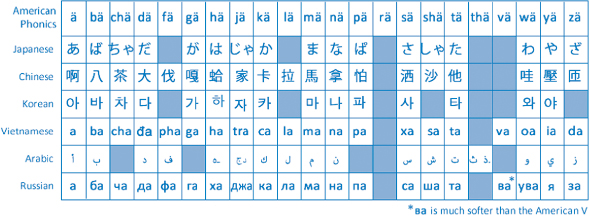

Other Characters

If you use one of these character sets, compare it with English.

Let me give a quick explanation of why we’re using these sounds. When you come in through your own language, you are coming from a place of total and absolute confidence. You know that sound. So, we’re taking something you know and doing a lateral transference to a set of letters in English. If, on the other hand, you start from scratch, you’ll be wondering if you’re doing it right, and this will drain your confidence and your energy.

Now that you’ve worked hard and successfully imitated the sounds, you’re going to go on to the next step, which is regular spelling.

Throughout this text, we will be using three symbols to indicate three separate actions:

|

Indicates a command or a suggestion. |

|

Indicates the beep tone. |

|

Indicates that you need to turn the audio on or off, back up, or pause. |

VOWEL & CONSONANT OVERVIEW: NONSENSE SYLLABLES

The first column is ä because it’s going to be easy for you. I’m going to say that again. Ready? It’s going to be easy for you. Why? Because as far as I can tell, every language on Earth has an ah sound. Some of the consonants may be a little tricky (TH and R spring to mind), but listen and repeat, repeat, repeat . . . in a deep voice. (Final consonants, diphthongs, and consonant blends such as BL and CR are covered in later chapters.)

*Most commonly used word in English

As you go through this chart, pronouncing all the sounds, deepen your voice and make the vowels a little longer than you are inclined to. Some of these will sound like real words, but most of them are just fragments. Observe that for ä, you drop your jaw, for ē, you stretch your lips back a bit, and for ū, you round your lips. There are only five new characters: ä, æ, ε,  , ü. Listen carefully and repeat this whole chart at least five times in columns, and five times across. Record yourself, listen back, and compare.

, ü. Listen carefully and repeat this whole chart at least five times in columns, and five times across. Record yourself, listen back, and compare.

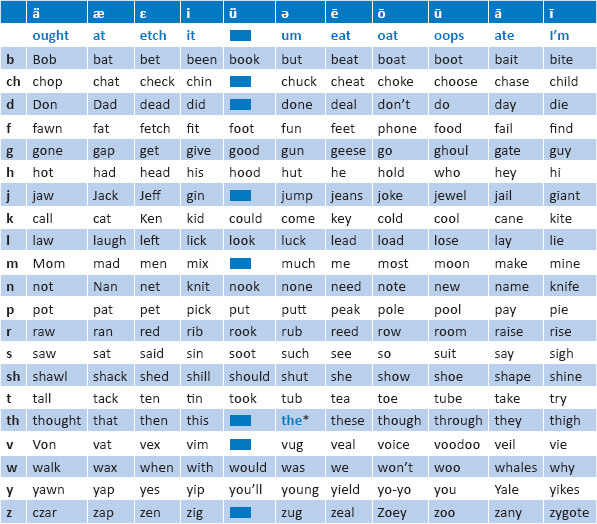

VOWEL & CONSONANT OVERVIEW: REAL WORDS

Apply the phonetic sound to the entire column, no matter what the spelling is. Then, read each row across, making the vowel distinctions.

*Most commonly used word in English

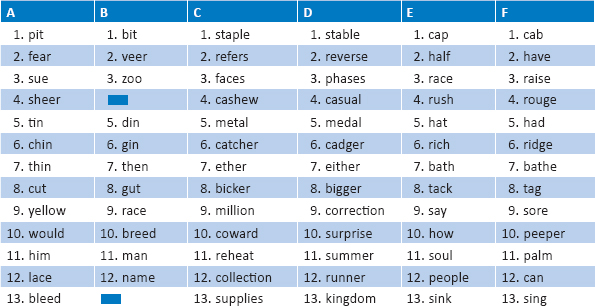

PRELIMINARY DIAGNOSTIC ANALYSIS

This is a speech analysis to identify the strengths and weaknesses of your American accent. If you are studying American Accent Training on your own, contact toll-free (800) 457-4255 or go to AmericanAccent.com for a referral to a qualified telephone analyst. The diagnostic analysis is designed to evaluate your current speech patterns to let you know where your accent is standard and nonstandard.

Hello, my name is ______. I’m taking American Accent Training. There’s a lot to learn, but I hope to make it as enjoyable as possible. I should pick up on the American intonation pattern pretty easily, although the only way to get it is to practice all of the time.

1.walk, all, long, caught

2.cat, matter, laugh

3.take, say, fail

4.get, any, says, fell

5.ice, I’ll, sky

6.tick, fill, will

7.teak, feel, wheel

8.work, first, learn, turn

9.tuck, fun, medicine, indicate

10.too, fool, wooed

11.took, full, would

12.woke, told, so, roll

13.out, house, round

14.loyal, choice, oil

1.Make him get it.

2.Let her get your keys.

3.You’ve got to work on it, don’t you?

4.Soup or salad?

1.Maykim geddit.

2.Ledder getcher keez.

3.Yoov gädda wr kä nit, doan choo?

4.Super salad?

1.Betty bought a bit of better butter.

2.Beddy bada bida bedder budder.

3.Italian |

Italy |

4.attack |

attic |

5.atomic |

atom |

6.photography |

photograph |

7.bet |

bed |