The tongue doesn’t touch anywhere. Growl out the R in the throat.

American English, today—although continually changing—is made up of the sounds of the various people who have come to settle here from many countries. All of them have put in their linguistic two cents, the end result being that the easiest way to pronounce things has almost always been adopted as the most American. R is an exception, along with L and the sounds of æ and th, and is one of the most troublesome sounds for people to acquire. Not only is it difficult for adults learning the language, but also for American children, who pronounce it like a W or skip over it altogether and only pick it up after they’ve learned all the other sounds. (See also Chapter 1 and the Nationality Guides.)

THE INVISIBLE R

The trouble is that you can’t see an R from the outside. With a P, for instance, you can see when people put their lips together and pop out a little puff. With R, however, everything takes place behind almost closed lips—back down in the throat—and who can tell what the tongue is doing? It is really hard to tell what’s going on if, when someone speaks, you can only hear the err sound, especially if you’re used to making an R by touching your tongue to the ridge behind your teeth. So, what should your tongue be doing? This technique can help you visualize the correct tongue movements in pronouncing the R.

1.Hold your hand out flat, with the palm up, slightly dropping the back end of it. That’s basically the position your tongue is in when you say ah ä, so your flat hand will represent this sound.

2.Now, to go from ah to the er, take your fingers and curl them into a tight fist. Again, your tongue should follow that action. The sides of your tongue should come up a bit, too. When the air passes over that hollow in the middle of your tongue, that’s what creates the er sound.

Try it using both your hand and tongue simultaneously. Say ah, with your throat open (and your hand flat), then curl your tongue up (and your fingers) and say errr. The tip of the tongue should be aimed at a middle position in the mouth, but never touching, and your throat should relax and expand. R, like L, has a slight schwa in it. This is what pulls the er down so far back in your throat.

Another way to get to er is to put a spoon on your tongue and go from the ee sound and slide your tongue straight back like a collapsing accordion, letting the two sides of your tongue touch the insides of your molars; the tip of the tongue, however, again, should not touch anything. Now from ee, pull your tongue back toward the center of your throat and pull the sound down into your throat:

ee  ee

ee  eeeer

eeeer

Since the R is produced in the throat, let’s link it with other throat sounds.

Exercise 5-1: R Location Practice |

Repeat after me.

g, gr, greek, green, grass, grow, crow, core, cork, coral, cur, curl, girl, gorilla, her, erg, error, mirror, were, war, gore, wrong, wringer, church, pearl

While you’re perfecting your R, you might want to rush to it, and in doing so, neglect the preceding vowel. There are certain vowels that you can neglect, but there are others that demand their full sound. We’re going to practice the ones that require you to keep that clear sound before you add an R.

Exercise 5-2: Double Vowel with R |

Refer to the subsequent lists of sounds and words as you work through each of the directions that follow them. Repeat each sound, first the vowel and then the  r, and each word in columns 1 to 3. We will read all the way across.

r, and each word in columns 1 to 3. We will read all the way across.

1 |

2 |

3 |

ä + |

hä• |

hard |

e + |

he• |

here |

ε + |

shε• |

share |

o + |

mo• |

more |

|

w |

were |

We will next read column 3 only; try to keep that doubled sound, but let the vowel flow smoothly into the  r; imagine a double stairstep that cannot be avoided. Don’t make them two staccato sounds, though, like ha•rd. Instead, flow them smoothly over the double stairstep: Hääärrrrd.

r; imagine a double stairstep that cannot be avoided. Don’t make them two staccato sounds, though, like ha•rd. Instead, flow them smoothly over the double stairstep: Hääärrrrd.

Of course, they’re not that long; this is an exaggeration, and you’re going to shorten them up once you get better at the sound. When you say the first one, hard, to get your jaw open for the hä, imagine that you are getting ready to bite into an apple: hä. Then, for the er sound, you would bite into it: hä•erd, hard.

Practice five times on your own.

Practice five times on your own.

From a spelling standpoint, the American R can be a little difficult to figure out. With words like where wε r and were w

r and were w r, it’s confusing to know which one has two different vowel sounds (where) and which one has just the

r, it’s confusing to know which one has two different vowel sounds (where) and which one has just the  r (were). When there is a full vowel, you must make sure to give it its complete sound and not chop it short, wε +

r (were). When there is a full vowel, you must make sure to give it its complete sound and not chop it short, wε +  r.

r.

For words with only the schwa + R  r, don’t try to introduce another vowel sound before the

r, don’t try to introduce another vowel sound before the  r, regardless of spelling. The following words, for example, do not have any other vowel sounds in them.

r, regardless of spelling. The following words, for example, do not have any other vowel sounds in them.

Looks like |

Sounds like |

word |

w |

hurt |

h |

girl |

g |

pearl |

p |

The following exercise will further clarify this for you.

Exercise 5-3: How to Pronounce Troublesome Rs |

The following seven R sounds, which are represented by the ten words, give people a lot of trouble, so we’re going to work with them and make them easy for you. Repeat.

1. |

were |

w |

2. |

word/whirred |

w |

3. |

whirl |

w |

4. |

world/whirled |

were rolled |

5. |

wore/war |

wo |

6. |

whorl |

worul |

7. |

where/wear |

wε |

1.Were is pronounced with a doubled  r: w

r: w r•

r• r

r

2.Word is also doubled, but after the second  r you’re going to put your tongue in place for the D and hold it there, keeping all the air in your mouth, opening your throat to give it that full-voiced quality (imagine yourself puffing your throat out like a bullfrog): w

r you’re going to put your tongue in place for the D and hold it there, keeping all the air in your mouth, opening your throat to give it that full-voiced quality (imagine yourself puffing your throat out like a bullfrog): w r

r rd, word. Not w

rd, word. Not w rd, which is too short. Not word

rd, which is too short. Not word , which is too strong at the end. But w

, which is too strong at the end. But w r•

r• rd word.

rd word.

3.In whirl the R is followed by L. The R is in the throat and the back of the tongue stays down because, as we’ve practiced, L starts with the schwa, but the tip of the tongue comes up for the L: w r•r

r•r •l

•l , whirl.

, whirl.

4.World/whirled, like 5 and 7, has two spellings (and two different meanings, of course). You’re going to do the same thing as for whirl, but you’re going to add that voiced D at the end, holding the air in: w r•r

r•r ld, world/ whirled. It should sound almost like two words: wére rolled.

ld, world/ whirled. It should sound almost like two words: wére rolled.

5.Here, you have an o sound in either spelling before the  r: wo•

r: wo• r, wore/war.

r, wore/war.

6.For whorl, you’re going to do the same thing as in 5, but you’re going to add a schwa + L at the end: wo• r

r l, whorl.

l, whorl.

7.This sound is similar to 5, but you have ε before the  r: wε•

r: wε• r, where/wear.

r, where/wear.

The following words are typical in that they are spelled one way and pronounced in another way. The ar combination frequently sounds like εr, as in embarrass embεr s. This sound is particularly clear on the West Coast. On the East Coast, you may hear embær

s. This sound is particularly clear on the West Coast. On the East Coast, you may hear embær s.

s.

Exercise 5-4: Zbigniew’s Epsilon List |

Repeat after me.

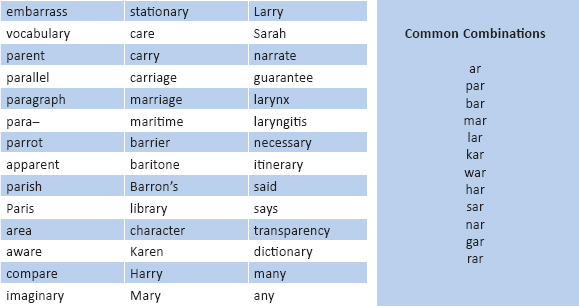

Exercise 5-5: R Combinations |

Don’t think about spelling here. Just pronounce each column of words as the heading indicates.

Exercise 5-6: The Mirror Store |

Repeat after me.

The Hurly Burly Mirror Store at Vermont and Beverly featured hundreds of first-rate mirrors. There were several mirrors on the chest of drawers,* and the largest one was turned toward the door in order to make the room look bigger. One of the girls who worked there was concerned that a bird might get hurt by hurtling into its own reflection. She learned by trial and error** how to preserve both the mirrors and the birds. Her earnings were proportionately increased at the mirror store to reflect her contribution to the greater good.

*chesta drorz

**tryla nerr’r

Practice reading out loud three times on your own.

Practice reading out loud three times on your own.

Go through our familiar paragraph and find all the R sounds. The first one is marked for you in blue.

Hello, my name is ________. I’m taking American Accent Training. There’s a lot to learn, but I hope to make it as enjoyable as possible. I should pick up on the American intonation pattern pretty easily, although the only way to get it is to practice all of the time. I use the up and down, or peaks and valleys, intonation more than I used to. I’ve been paying attention to pitch, too. It’s like walking down a staircase. I’ve been talking to a lot of Americans lately, and they tell me that I’m easier to understand. Anyway, I could go on and on, but the important thing is to listen well and sound good. Well, what do you think? Do I?

Click here for answers.

Click here for answers.

One of the best ways to get the R is to literally growl.

Say grrrr as if you were a wild animal growling in the woods.

VOICED CONSONANTS AND REDUCED VOWELS

The strong intonation in American English creates certain tendencies in your spoken language. Here are four consistent conditions that are a result of intonation’s tense peaks and relaxed valleys:

1. Reduced vowels

You were introduced to reduced vowels in Chapter 1. They appear in the valleys that are formed by the strong peaks of intonation. The more you reduce the words in the valleys, the smoother and more natural your speech will sound. A characteristic of reduced vowels is that your throat muscles should be very relaxed. This will allow the unstressed vowels to reduce toward the schwa. Neutral vowels take less energy and muscularity to produce than tense vowels. For example, the word unbelievable should only have one hard vowel:  nb

nb lēv

lēv b

b l.

l.

2. Voiced consonants

The mouth muscles are relaxed to create a voiced sound like z or d. For unvoiced consonants, such as s or t, they are sharp and tense. Relaxing your muscles will simultaneously reduce your vowels and voice your consonants. Think of voiced consonants as reduced consonants. Both reduced consonants and reduced vowels are unconsciously preferred by a native speaker of American English. This explains why T so frequently becomes D and S becomes Z: Get it is to . . . gedidizd .

.

3. Like sound with like sound

It’s not easy to change horses midstream, so when you have a voiced consonant let the consonant that follows it be voiced as well. In the verb used yuzd, for example, the S is really a Z, so it is followed by D. The phrase used to yus tu, on the other hand, has a real S, so it is followed by T. Vowels are, by definition, voiced. So when one is followed by a common, reducible word, it will change that word’s first sound—like the preposition to, which will change to d .

.

The only way to get it is to practice all of the time.

They only wei•d •geddidiz•d

•geddidiz•d •practice all of the time.

•practice all of the time.

Again, this will take time. In the beginning, work on recognizing these patterns when you hear them. When you are confident that you understand the structure beneath these sounds and you can intuit where they belong, you can start to try them out. It’s not advisable to memorize one reduced word and stick it into an otherwise overpronounced sentence. It would sound strange.

4. R’lææææææææææx

You’ve probably noticed that the preceding three conditions, as well as other areas that we’ve covered, such as liaisons and the schwa, have one thing in common—the idea that it’s physically easier this way. This is one of the most remarkable characteristics of American English. You need to relax your mouth and throat muscles (except for æ, ä, and other tense vowels) and let the sounds flow smoothly out. If you find yourself tensing up, pursing your lips, or tightening your throat, you are going to strangle and lose the sound you are pursuing. Relax, relax, relax.