Unstressed words have reduced vowels.

THE DOWN SIDE OF INTONATION

Reduced sounds are all those extra sounds created by an absence of lip, tongue, jaw, and throat movement. They are a principal function of intonation and are truly indicative of the American sound. (See also Chapter 1.)

Reduced Sounds Are “Valleys”

American intonation is made up of peaks and valleys—tops of staircases and bottoms of staircases. To have strong peaks, you will have to develop deep valleys. These deep valleys should be filled with all kinds of reduced vowels, one in particular—the completely neutral schwa. Ignore spelling. Since you probably first became acquainted with English through the printed word, this is going to be quite a challenge. The position of a syllable is more important than spelling as an indication of correct pronunciation. For example, the words photograph and photography each have two O’s and an A. The first word is stressed on the first syllable, so photograph sounds like fod’græf. The second word is stressed on the second syllable, photography, so the word comes out f’tahgr’fee. You can see here that their spelling doesn’t tell you how they sound. Word stress or intonation will determine the pronunciation. Work on listening to words. Concentrate on hearing the pure sounds, not on trying to make the word fit a familiar spelling. Otherwise, you will be taking the long way around and giving yourself both a lot of extra work and an accent!

Syllables that are perched atop a peak or a staircase are strong sounds; that is, they maintain their original pronunciation. On the other hand, syllables that fall in the valleys or on a lower stairstep are weak sounds; thus, they are reduced. Some vowels are reduced completely to schwas, a very relaxed sound, while others are only toned down. In the following exercises, we will be dealing with these “toned down” sounds.

In the introduction (“Read This First”) I talked about overpronouncing. This section will handle that overpronunciation. You’re going to skim over words; you’re going to dash through certain sounds. Your peaks are going to be quite strong, but your valleys, blurry—a very intuitive aspect of intonation that this practice will help you develop.

Articles (such as the, a) are usually very reduced sounds. Before a consonant, the and a are both schwa sounds, which are reduced. Before a vowel, however, you’ll notice a change—the schwa of the turns into a long e plus a connecting (y)—Th’ book changes to thee(y)only book; A hat becomes a nugly hat. The article a becomes an. Think of  •nornj rather than an orange;

•nornj rather than an orange;  •nopening,

•nopening,  •neye,

•neye,  •nimaginary animal.

•nimaginary animal.

Exercise 7-1: Reducing Articles |

Listen and repeat.

When you used the rubber band with Däg zeet bounz and when you built your own sentence, you saw that intonation reduces the unstressed words. Intonation is the peak and reduced sounds are the valleys. In the beginning, you should make extra-high peaks and long, deep valleys. When you are not sure, reduce. In the following exercise, work with this idea. Small words such as articles, prepositions, pronouns, conjunctions, relative pronouns, and auxiliary verbs are lightly skimmed over and almost not pronounced.

You have seen how intonation changes the meaning in words and sentences. Inside a one-syllable word, it distinguishes between a final voiced or unvoiced consonant be-ed and bet. Inside a longer word, éunuch versus unίque, the pronunciation and meaning change in terms of vocabulary. In a sentence (He seems nice; He seems nice.), the meaning changes in terms of intent.

In a sentence, intonation can also make a clear vowel sound disappear. When a vowel is stressed, it has a certain sound; when it is not stressed, it usually sounds like uh, pronounced  . Small words like to, at, or as are usually not stressed, so the vowel disappears.

. Small words like to, at, or as are usually not stressed, so the vowel disappears.

Exercise 7-2: Reduced Sounds |

Read aloud from the right-hand column. The intonation is marked for you.

To |

Looks Like . . . |

Sounds Like . . . |

The preposition to usually reduces so much that it’s like dropping the vowel. |

today |

t’day |

tonight |

t’night |

|

tomorrow |

t’märou |

|

to work |

t’wrk |

|

to school |

t’ school |

|

to the store |

t’ th’ store |

|

|

|

|

Use a t’ or t |

We have to go now. |

we hæftә go næo |

He went to work |

he wentә work |

|

They hope to find it. |

they houptә fine dit |

|

|

I can’t wait to find out. |

äi cæn(t)wai(t)tә fine dæot |

|

We don’t know what to do. |

we dont know w’(t)t’ do |

|

Don’t jump to conclusions. |

dont j’m t’ c’ncloozh’nz |

|

To be or not to be . . . |

t’bee(y)r nät t’ bee |

|

He didn’t get to go. |

he din ge(t)tә gou |

If that same to follows a vowel sound, it will become d’ or d |

He told me to help. |

he told meedә help |

She told you to get it. |

she tol joodә geddit |

|

I go to work |

ai goudә wrk |

|

at a quarter to two |

ædә kworder dә two |

|

The only way to get it is . . . |

thee(y)only waydә geddidiz |

|

|

You’ve got to pay to get it. |

yoov gäddә paydә geddit |

|

We plan to do it. |

we plæn dә do it |

|

Let’s go to lunch. |

lets goudә lunch |

|

The score was 4–6. |

th’ score w’z for dә six |

|

It’s the only way to do it. |

its thee(y)ounly weidә do(w)’t |

|

So to speak . . . |

soda speak |

|

I don’t know how to say it. |

äi don(t)know hæwdә say(y)it |

|

Go to page 8. |

goudә pay jate |

|

Show me how to get it. |

show me hæodә geddit |

|

You need to know when to do it. |

you nee(d)dә nou wendә do(w)it |

|

Who’s to blame? |

hooz dә blame |

|

|

|

At |

We’re at home. |

wirәt home |

At is just the opposite of to. It’s a small grunt followed by a reduced t. |

I’ll see you at lunch. |

äiyәl see you(w)әt lunch |

Dinner’s at five. |

d’nnerzә(t) five |

|

Leave them at the door. |

leevәmә(t)thә door |

|

The meeting’s at one. |

th’ meeding z’t w’n |

|

He’s at the post office. |

heezә(t)the poussdäffәs |

|

|

They’re at the bank. |

thεrә(t)th’ bænk |

|

I’m at school. |

äimә(t)school |

|

|

|

If at is followed by a vowel sound, it will become ’d or |

I’ll see you at eleven. |

äiyәl see you(w)әdә lεv’n |

He’s at a meeting. |

heez’ dә meeding |

|

She laughed at his idea. |

she læf dәdi zy deeyә |

|

One at a time |

wәnәdә time |

|

|

We got it at an auction. |

we gädidәdә näksh’n |

|

The show started at eight. |

th’ show stardәdә date |

|

The dog jumped out at us. |

th’ däg jump dæo dәdәs |

|

I was at a friend’s house. |

äi w’z’d’ frenz hæos |

It |

Can you do it? |

k’niu do(w)’t |

|

|

|

It and at sound the same in context—’t |

Give it to me. |

g’v’(t)t’ me |

Buy it tomorrow. |

bäi(y)ә(t)t’ märrow |

|

It can wait. |

‘t c’n wait |

|

Read it twice. |

ree d’(t)twice |

|

|

Forget about it! |

frgedd’ bæodit |

|

|

|

. . . and they both turn to ’d or |

Give it a try. |

gividә try |

Let it alone. |

ledidә lone |

|

Take it away. |

tay kida way |

|

I got it in London. |

äi gädidin l’nd’n |

|

What is it about? |

w’d’z’d’bæot |

|

|

Let’s try it again. |

lets try’d’ gen |

|

Look! There it is! |

lük there’d’z |

For |

This is for you. |

th’s’z fr you |

|

It’s for my friend. |

ts fr my friend |

|

A table for four, please. |

table fr four, pleeze |

|

We planned it for later. |

we plan dit fr layd’r |

|

For example, for instance |

fregg zæmple frin st’nss |

|

What is this for? |

w’d’z this for(for is not reduced at the end of a sentence) |

|

What did you do it for? |

w’j’ do(w)it for |

|

Who did you get it for? |

hoojya geddit for |

|

|

|

From |

It’s from the IRS. |

ts frm thee(y)äi(y)ä ress |

|

I’m from Arkansas. |

äim fr’m ärk’ nsä |

|

There’s a call from Bob. |

therzә cäll fr’m Bäb |

|

This letter’s from Alaska! |

this ledderz frәmә læsk |

|

Who’s it from? |

hoozit frәm |

|

Where are you from? |

wher’r you frәm |

|

|

|

In |

It’s in the bag. |

tsin thә bæg |

|

What’s in it? |

w’ts’n’t |

|

I’ll be back in a minute. |

äiyәl be bæk’nә m’n’t |

|

This movie? Who’s in it? |

this movie . . . hooz’n’t |

|

Come in. |

c ‘min |

|

He’s in America. |

heez’nә mεrәkә |

|

|

|

An |

He’s an American. |

heez’nә mεrәkәn |

|

I got an A in English. |

äi gäddә nay ih ninglish |

|

He got an F in Algebra. |

hee gäddә neffinæl jәbrә |

|

He had an accident. |

he hædә næksәd’nt |

|

We want an orange. |

we want’n nornj |

|

He didn’t have an excuse. |

he didnt hævә neks kyooss |

|

I’ll be there in an instant. |

äi(y)’l be there inә ninstnt |

|

It’s an easy mistake to make. |

itsә neezee m’ stake t’ make |

|

|

|

And |

ham and eggs |

hæmә neggz |

|

bread and butter |

bredn buddr |

|

Coffee? With cream and sugar? |

käffee . . . with creem’n sh’g’r |

|

No, lemon and sugar. |

nou . . . lem’n’n sh’g’r |

|

. . . And some more cookies? |

’n smore cükeez |

|

They kept going back and forth. |

they kep going bækn forth |

|

We watched it again and again. |

we wäch didә gen’n’ gen |

|

He did it over and over. |

he di di doverә nover |

|

We learned by trial and error. |

we lrnd by tryәlәnerәr |

|

|

|

Or |

Soup or salad? |

super salad |

|

now or later |

næ(w)r laydr |

|

more or less |

mor’r less |

|

left or right |

lefter right |

|

For here or to go? |

f’r hir’r d’go |

|

Are you going up or down? |

are you going úpper dόwn |

|

This is an either / or question: Up? Down? |

|

|

Notice how the intonation is different from “Cream and sugar?”, which is a yes / no question. |

|

|

|

|

Are |

What are you doing? |

w’dr you doing |

|

Where are you going? |

wer’r you going |

|

What’re you planning on doing? |

w’dr yü planning än doing |

|

How are you? |

hæwr you |

|

Those are no good. |

thozer no good |

|

How are you doing? |

hæwer you doing |

|

The kids are still asleep. |

the kidzer stillә sleep |

|

|

|

Your |

How’s your family? |

hæozhier fæmlee |

|

Where’re your keys? |

wher’r y’r keez |

|

You’re American, aren’t you? |

yerә mer’k’n, arn choo |

|

Tell me when you’re ready. |

tell me wen yr reddy |

|

Is this your car? |

izzis y’r cär |

|

You’re late again, Bob. |

yer lay dә gen, Bäb |

|

|

|

One |

Which one is yours? |

which w’n’z y’rz |

|

Which one is better? |

which w’n’z bedder |

|

One of them is broken. |

w’n’v’m’z brok’n |

|

I’ll use the other one. |

æl yuz thee(y)әther w’n |

|

I like the red one, Edwin. |

äi like the redw’n, edw’n |

|

That’s the last one. |

thæts th’ lass dw’n |

|

The next one’ll be better. |

the necks dw’n’ll be bedd’r |

|

Here’s one for you. |

hir zw’n f’r you |

|

Let them go one by one. |

led’m gou w’n by w’n |

|

|

|

The |

It’s the best. |

ts th’ best |

|

What’s the matter? |

w’ts th’ madder |

|

What’s the problem? |

w’tsә präbl’m |

|

I have to go to the bathroom. |

äi hæf t’ go d’ th’ bæthroom |

|

Who’s the boss around here? |

hoozә bäss sәræond hir |

|

Give it to the dog. |

g’v’(t)tә th’ däg |

|

Put it in the drawer. |

püdidin th’ dror |

|

|

|

A |

It’s a present. |

tsә preznt |

|

You need a break. |

you needә bray-eek |

|

Give him a chance. |

g’v’mә chæns |

|

Let’s get a new pair of shoes. |

lets geddә new perә shooz |

|

Can I have a Coke, please? |

c’nai hævә kouk, pleez |

|

Is that a computer? |

izzædә k’mpyoodr |

|

Where’s a public telephone? |

wherzә pәblic telәfoun |

|

|

|

Of |

It’s the top of the line. |

tsә täp’v th’ line |

|

It’s a state of the art printer. |

tsә stay dә thee(y)ärt prinner |

|

As a matter of fact, . . . |

z’mædderә fækt . . . |

|

Get out of here. |

geddæow dә hir |

|

Practice all of the time. |

prækt’säll’v th’ time |

|

Today’s the first of May. |

t’dayz th’ frss d’v May |

|

What’s the name of that movie? |

w’ts th’ nay m’v thæt movie |

|

That’s the best of all! |

thæts th’ bess d’väll |

|

some of them |

sәmәvәm |

|

all of them |

ällәvәm |

|

most of them |

mosdәvәm |

|

none of them |

nәnәvәm |

|

any of them |

ennyәvәm |

|

the rest of them |

th’ resdәvәm |

|

|

|

Can |

Can you speak English? |

k’new spee kinglish |

|

I can only do it on Wednesday. |

äi k’nounly du(w)idän wenzday |

|

A can opener can open cans. |

kænop’ner k’nopen kænz |

|

Can I help you? |

k’näi hel piu |

|

Can you do it? |

k’niu do(w)’t |

|

We can try it later. |

we k’n try it layder |

|

I hope you can sell it. |

äi hou piu k’n sell’t |

|

No one can fix it. |

nou w’n k’n fick sit |

|

Let me know if you can find it. |

lemme no(w)’few k’n fine dit |

|

|

|

Had |

Jack had had enough. |

jæk’d hæd’ n’f |

|

Bill had forgotten again. |

bil’d frga(t)n nә gen |

|

What had he done to deserve it? |

w’d’dee d’nd’d’ zr vit |

|

We’d already seen it. |

weedäl reddy see nit |

|

He’d never been there. |

heed never bin there |

|

Had you ever had one? |

h’jou(w)ever hædw’n |

|

Where had he hidden it? |

wer dee hidnonit |

|

Bob said he’d looked into it. |

bäb sedeed lükdin tu(w)it |

|

|

|

Would |

He would have helped, if . . . |

he wüda help dif . . . |

|

Would he like one? |

woody lye kw’n |

|

Do you think he’d do it? |

dyiu thing keed du(w)’t |

|

Why would I tell her? |

why wüdäi teller |

|

We’d see it again, if . . . |

weed see(y)idәgen, if . . . |

|

He’d never be there on time. |

heed never be therän time |

|

Would you ever have one? |

w’jou(w)ever hævw’n |

|

|

|

Was |

He was only trying to help. |

he w’zounly trying dә help |

|

Mark was American. |

mär kw’z’mer’k’n |

|

Where was it? |

wer w’z’t |

|

How was it? |

hæow’z’t |

|

That was great! |

thæt w’z great |

|

Who was with you? |

hoow’z with you |

|

She was very clear. |

she w’z very clear |

|

When was the war of 1812? |

wen w’z th’ wor’v ei(t)teen twelv |

|

|

|

What |

What time is it? |

w’t tye m’z’t |

|

What’s up? |

w’ts’p |

|

What’s on your agenda? |

w’tsänyrә jendә |

|

What do you mean? |

w’d’y’ mean |

|

What did you mean? |

w’j’mean |

|

What did you do about it? |

w’j’ du(w)әbæodit |

|

What took so long? |

w’t tük so läng |

|

What do you think of this? |

w’ddyә thing k’v this |

|

What did you do then? |

w’jiu do then |

|

I don’t know what he wants. |

I dont know wәdee wänts |

|

|

|

Some |

Some are better than others. |

s’mr beddr thәnәtherz |

|

There are some leftovers. |

ther’r s’m lef doverz |

|

Let’s buy some ice cream. |

let spy s’ mice creem |

|

Could we get some other ones? |

kwee get s’mother w’nz |

|

Take some of mine. |

take sәmәv mine |

|

Would you like some more? |

w’ joo like s’more |

|

(or, very casually) |

jlike smore |

|

Do you have some ice? |

dyü hæv sәmice |

|

Do you have some mice? |

dyü hæv sәmice |

“You can fool some of the people some of the time,

but you can’t fool all of the people all of the time.”

yuk’n fool s m

m th

th peep

peep l s

l s m

m th

th time, b’choo kænt fool äll

time, b’choo kænt fool äll th

th peep

peep l äll

l äll th

th time

time

Exercise 7-3: Intonation and Pronunciation of “That” |

That is a special case because it serves three different grammatical functions. The relative pronoun and the conjunction are reducible. The demonstrative pronoun cannot be reduced to a schwa sound. It must stay æ.

Relative Pronoun |

The car that she ordered is red. |

the car th’t she order diz red |

Conjunction |

He said that he liked it. |

he sed the dee läikdit. |

Demonstrative |

Why did you do that? |

why dijoo do thæt? |

Combination |

I know that he’ll read that book that I told you about. |

äi know the dill read thæt bük the dai toljoo(w)’ bæot |

Exercise 7-4: Crossing Out Reduced Sounds |

Cross out any sound that is not clearly pronounced, including to, for, and, that, than, the, a, the soft i, and unstressed syllables that do not have strong vowel sounds.

Hello, my name is ________. I’m taking American Accent Training. There’s a lot to learn, but I hope to make it as enjoyable as possible. I should pick up on the American intonation pattern pretty easily, although the only way to get it is to practice all of the time. I use the up and down, or peaks and valleys, intonation more than I used to. I’ve been paying attention to pitch, too. It’s like walking down a staircase. I’ve been talking to a lot of Americans lately, and they tell me that I’m easier to understand. Anyway, I could go on and on, but the important thing is to listen well and sound good. Well, what do you think? Do I?

Exercise 7-5: Reading Reduced Sounds |

Repeat the paragraph after me. Although you’re getting rid of the vowel sounds, you want to maintain a strong intonation and let the sounds flow together. For the first reading of this paragraph, it is helpful to keep your teeth clenched together to reduce excess jaw and lip movement. Let’s begin.

Hello, my name’z ______. I’m taking ’mer’k’n Acc’nt Train’ng. Therez’ lott’ learn, b’t I hope t’ make ’t’z ’njoy’bl’z poss’bl. I sh’d p’ck ’p on the ’mer’k’n ’nt’nash’n pattern pretty eas’ly, although the only way t’ get ’t ’z t’ pract’s all ’v th’ time. I use the ’p’n down, or peaks ’n valleys, ’nt’nash’n more th’n I used to. Ive b’n pay’ng ’ttensh’n t’ p’ch, too. ’Ts like walk’ng down’ staircase. Ive b’n talk’ng to’ lot ’v’mer’k’ns lately, ’n they tell me th’t Im easier to ’nderstand. Anyway, I k’d go on ’n on, b’t the ’mport’nt th’ng ’z t’ l’s’n wel’n sound g’d. W’ll, wh’ d’y’ th’nk? Do I?

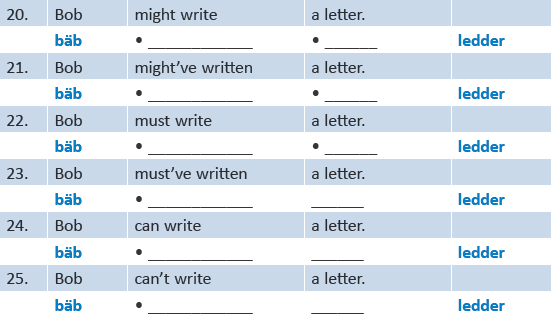

Even in complex sentences, stress the noun (unless there is contrast).

Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Grammar but Were Afraid to Use

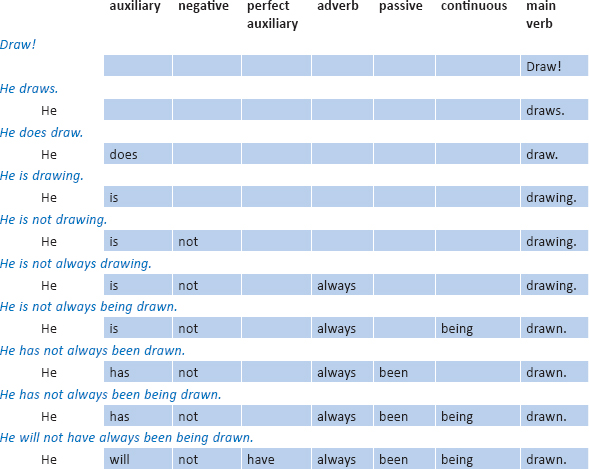

English is a chronological language. We just love to know when something happened, and this is indicated by the range and depth of our verb tenses.

I had already seen it by the time she brought it in.

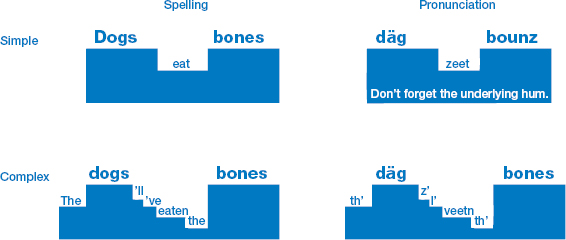

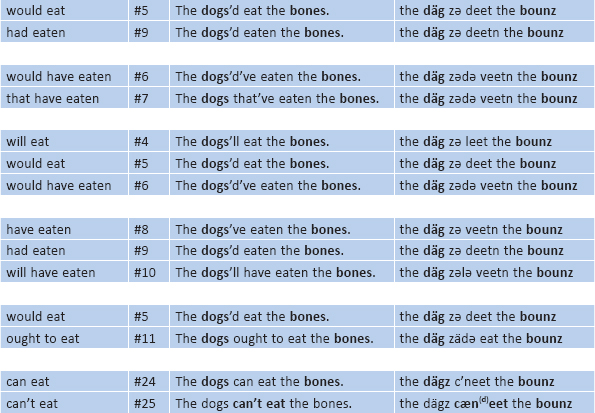

The confusing part is that in English the verb tenses are very important, but instead of putting them up on the peaks of a sentence, we throw them all deep down in the valleys! Therefore, two sentences with strong intonation—such as, “Dogs eat bones” and “The dogs’ll’ve eaten the bones”—sound amazingly similar. Why? Because it takes the same amount of time to say both sentences since they have the same number of stresses. The three original words and the rhythm stay the same in these sentences, but the meaning changes as you add more stressed words. Articles and verb tense changes are usually not stressed.

Now, let’s see how this works in the exercises that follow.

Exercise 7-6: Consistent Noun Stress in Changing Verb Tenses |

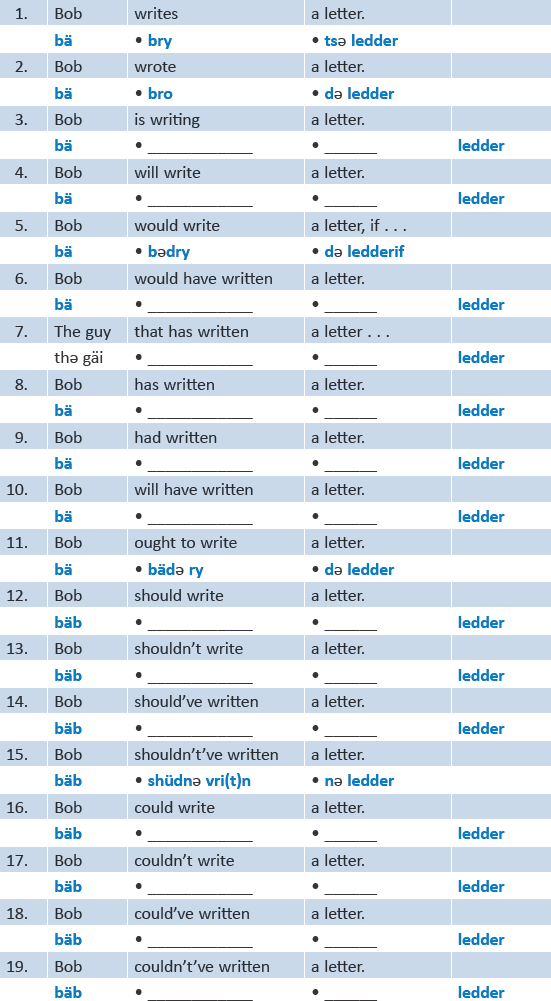

This is a condensed exercise for you to practice simple intonation with a wide range of verb tenses. When you do the exercise the first time, go through stressing only the nouns: Dogs eat bones. Practice this until you are quite comfortable with the intonation. The pronunciation and word connections are on the right, and the full verb tenses are on the far left.

Exercise 7-7: Consistent Pronoun Stress in Changing Verb Tenses |

This is the same as the previous exercise, except you now stress the verbs: They eat them. Practice this until you are quite comfortable with the intonation. Notice that in fluent speech, the th of them is frequently dropped (as is the h in the other object pronouns, him, her). The pronunciation and word connections are on the right, and the tense name is on the far left.

In the blanks below, fill in the phonetic pronunciation (using the guidelines from Exercise 7-6). Remember, don’t rely on spelling, and use the contracted forms wherever possible. (Click on the hyperlinks in the first column to check your answers.)

Exercise 7-9: Supporting Words |

For this next part of the intonation of grammatical elements, each sentence has a few extra words to help you get the meaning. Keep the same strong intonation that you used before and add the new stress where you see the bold face. Use your rubber band.

The dogs eat the bones every day. |

th’ däg zeet th’ bounzevree day |

The dogs ate the bones last week. |

th’ däg zεit th’ bounzlæss dweek |

The dogs’re eating the bones right now. |

th’ däg zr reeding th’ bounz räit næo |

The dogs’ll eat the bones if they’re here. |

th’ däg z |

The dogs’d eat the bones if they were here. |

th’ däg z |

The dogs’d’ve eaten the bones if they’d been here. |

th’ däg z |

The dogs that’ve eaten the bones are sick. |

th’ däg z |

The dogs’ve eaten the bones every day. |

th’ däg z |

The dogs’d eaten the bones by the time we got there. |

th’ däg z |

The dogs’ll have eaten the bones by the time we get there. |

th’ däg z |

English has a fixed word order that does not change with additional words.

Exercise 7-10: Contrast Practice |

Now, let’s work with contrast. For example, The dogs’d eat the bones and The dogs’d eaten the bones are so close in sound, yet so far apart in meaning, that you need to make a special point of recognizing the difference by listening for content. Repeat each group of sentences, originally from Exercise 7-6, as noted by the numbers in the second column, using sound and intonation for contrast.

Exercise 7-11: Building an Intonation Sentence |

Repeat after me.

1.I bought a sandwich.

2.I said I bought a sandwich.

3.I said I think I bought a sandwich.

4.I said I really think I bought a sandwich.

5.I said I really think I bought a chicken sandwich.

6.I said I really think I bought a chicken salad sandwich.

7.I said I really think I bought a half a chicken salad sandwich.

8.I said I really think I bought a half a chicken salad sandwich this afternoon.

9.I actually said I really think I bought a half a chicken salad sandwich this afternoon.

10.I actually said I really think I bought another half a chicken salad sandwich this afternoon.

11.Can you believe I actually said I really think I bought another half a chicken salad sandwich this afternoon?

1.I did it.

2.I did it again.

3.I already did it again.

4.I think I already did it again.

5.I said I think I already did it again.

6.I said I think I already did it again yesterday.

7.I said I think I already did it again the day before yesterday.

1.I want a ball.

2.I want a large ball.

3.I want a large, red ball.

4.I want a large, red, bouncy ball.

5.I want a large, red, bouncy rubber ball.

6.I want a large, red, bouncy rubber basketball.

1.I want a raise.

2.I want a big raise.

3.I want a big, impressive raise.

4.I want a big, impressive, annual raise.

5.I want a big, impressive, annual cost of living raise.

Exercise 7-12: Building Your Own Intonation Sentences |

Build your own sentence using everyday words and phrases, such as think, hope, nice, really, actually, even, this afternoon, big, small, pretty, and so on.

1. |

|

2. |

|

3. |

|

4. |

|

5. |

|

6. |

|

7. |

|

8. |

|

9. |

|

10. |

|

BREATHING EXERCISES

Different languages have different breathing patterns. Because Americans are a little louder than you may expect, in order to emulate this projection of the voice, you’re going to have to take deeper breaths than you’re accustomed to. Stand up straight, chest out, inhale deeply, and in a deep voice say, “Hi! How’s it going?”

As you saw with Phrasing, your breathing should be in sync with the phrasing and punctuation. If you’re saying something short, you can get away with a more shallow inhale, but short panting breaths are interpreted as nervous or impatient, whereas long, deep exhalations of sound are considered calm and confident. Take deeper breaths than usual and push the sound out from deep in your chest.

Pay particular attention that you do not push the air out through your nose, which would create a very unattractive nasal quality to your speech. (Practice with the long sentences in exercises 7-6 - 7-11 and 14-1.)