HOW DO YOU TELL THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A MALE JEWISH COMEDIAN AND A FEMALE JEWISH COMEDIAN?

Alexander Portnoy complains that ‘I am the son in the Jewish joke – only it ain’t no joke!’ But it’s Sophie – the target not only of the Jewish joke’s internalised anti-Semitism, but of a large dose of misogyny as well – who can really be found drowning in the Jewish joke. So who will rescue her, another writer, Grace Paley, asks, from ‘her son the doctor and her son the novelist’?

Why, the female joker, of course!*

Yet there’s a nasty rumour abroad, you hear it again and again: women just aren’t as funny as men. To which you always want to reply: well, they try not to laugh in your face maybe. For women in public are much more bound by the conventions of civility – of having to please everyone all the time – that can make poking fun a riskier business for them. This was something that the late Joan Rivers, perhaps the most caustic of female comics, understood only too well. ‘One of the most rebellious things a woman can do,’ she once said, ‘is allow people to think she’s mean.’ The mere fact, in other words, of a woman going public with her funniness can throw a certain light on the degree to which a misogynist culture has turned comedy – including Jewish comedy – into an ultradefensive boys’ club.

Not that it’s so hard sending up the boys:

My ancestors wandered lost in the wilderness for forty years because even in biblical times, men would not stop to ask for directions. Elayne Boosler

Most men are secretly still mad at their mothers for throwing away their comic books. They would be valuable now. Rita Rudner

My mother always said don’t marry for money. Divorce for money. Wendy Liebman

I don’t have any kids. Well, at least none I know about. Cathy Ladman

But female comedians do more than simply deliver low blows where they know it hurts. They also use their acts to critique the stratagems of male-centric comedy. When, that is, we hear men’s jokes told by women, we cannot but hear them differently – hence why that line from Cathy Ladman, which word for word parrots a stereotypically male comedy brag, is about as deft a moment of comic outwitting as you could wish for.

And the same logic goes doubly when women tell jokes about areas of female experience that no male comic should reasonably expect to get away with. Here, for instance, is Sarah Silverman:

I was raped by a doctor, which is so bittersweet for a Jewish girl.

To my ears, there’s a world of difference between this and a male-authored ‘rape joke’, but not everyone believes that gender does anything to justify such a gag. And that, in a nutshell, is the trouble for the comedian – and especially the female comedian, whose use of obscenity or brashness always sparks greater outrage – there are those who will be scandalised by pretty much every joke she tells. Hence the advice of Joan Rivers: ‘We don’t apologise for a joke. We are comics. We are here to make you laugh. If you don’t get it, then don’t watch us.’

Such advice can only be inspirational for Sarah Silverman. Because it’s true, Silverman’s Jewish jokes have upset certain Jews, and her rape jokes have upset certain women – including certain Jewish women* – and it’s true too that Silverman has stood accused, as Philip Roth was in the 1960s, of self-hatred. So with an act like Silverman’s we can find, once again, the same old questions getting asked: is such comedy needlessly offensive? Is it, all told, even witty? And is it, ultimately, defensible or indefensible?

And, as ever, context is everything: it always depends on who is telling the joke, who is hearing it, and to what end. Roth, for instance, has assured us that he has yet to receive a letter of thanks from an anti-Semitic organisation. And so far as I’m aware, misogynists haven’t written to thank Silverman for her great services to their cause either. So while it’s important to be mindful of sensitivities, it’s just as important to remain wary of the humour police, those punchline vigilantes who so often wind up silencing the very people they’re claiming to defend. For though, in the majority of situations, humour is seldom the only answer, and by no means always the best one, what humourlessness always fails to recognise is just how useful a sense of humour can be for confronting what one finds offensive, including offensive jokes – as can be seen from the long tradition of comedians wrong-footing their abusers by making the mud slung their way a valuable commodity: material they can work with.

Take, for example, another young Jewish American comedian, Amy Schumer, who sparked the predictable yowls of outrage after tweeting this image of herself:

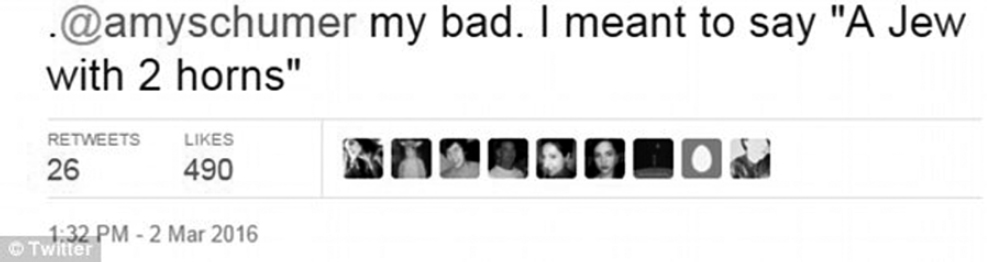

And who then doubled the ‘offence’ by parodying the demand for an apology in her follow-up tweet:

Some allege that such quips see Schumer reinforcing the ugly stereotyping of Jews throughout their history. But can’t we regard them instead as an intervention into that history? Because what we find with playfulness like Schumer’s is not anti-Semitism, surely, but quite the opposite: a seriously funny Jewish woman taking on history by the horns.

* ‘At least, when she isn’t self-harming or being taken to task for doing so. Alluding to fellow Jewish ‘funny girl’ Fanny Brice’s rhinoplasty in 1923, Dorothy Parker quipped that Brice had ‘cut off her nose to spite her race.’

* ‘Put me up against Sarah Silverman and I could take her’ Joan Rivers.