HOW DO YOU TELL THE DIFFERENCE?

On Passover, Jews ask the question ‘Why is this night different from all other nights?’ But is it so different? Not in one respect, at least: asking why anything is different from anything else isn’t especially unusual for Jews.

If Jews love anything, it’s telling the difference. What’s kosher or unkosher? Milky or meaty? Circumcised or uncircumcised? Thirst or diabetes? In yeshivas (religious schools), Jews study the Talmud and the law, always with an eye on how to tell the minutest distinctions between seemingly similar things. Sometimes the difference simply comes down to how you ask the question:

Two yeshiva students, Yankel and Moshe, discuss whether it is permitted to smoke while learning Torah. They disagree. Yankel says, ‘I will go and ask the rabbi.’

Yankel: ‘Rabbi, is it permitted to smoke while learning Torah?’

Rabbi states in a severe tone: ‘No!’

Moshe: ‘Rabbi, let me ask you another question. May we learn Torah while we smoke?’

Rabbi, benign: ‘Yes, of course!’

But at other times differences are maintained far more strictly:

A modern, orthodox Jewish couple, preparing for a religious wedding, meet with their rabbi. The rabbi asks if they have any last questions before they leave.

The man asks, ‘Rabbi, we realise it’s tradition for men to dance with men, and women to dance with women, at the reception. But we’d like your permission to dance together.’

‘Absolutely not,’ says the rabbi. ‘It’s immodest. Men and women always dance separately.’

‘So after the ceremony I can’t even dance with my own wife?’

‘No,’ answered the rabbi. ‘It’s forbidden.’

‘Well, OK,’ says the man, ‘what about sex? Can we finally have sex?’

‘Of course!’ replies the rabbi. ‘Sex is a mitzvah within marriage.’

‘What about different positions?’ asks the man.

‘No problem,’ says the rabbi. ‘It’s a mitzvah!’

‘Woman on top?’ the man asks.

‘Sure,’ says the rabbi. ‘Go for it!’

‘Doggy style?’

‘Sure! Another mitzvah!’

‘Yes, yes! A mitzvah!’

‘Can we do it standing up?’

‘No,’ says the rabbi.

‘Why not?’ asks the man.

‘It could lead to dancing!’

This obsession with telling the difference forms a big part of Alexander Portnoy’s complaint about a family endlessly invested in keeping up with the Cohens and telling their difference from the Joneses – not to mention their effort to keep up with the Joneses and tell their difference from the Cohens. And it was precisely this kind of pointscoring that Freud also identified and called ‘the narcissism of small differences’ (show-off). Lenny Bruce, meanwhile, tells the difference between Jewish and goyish differently – but still, the point is he tells it.

However if ‘How do you tell the difference?’ is the Jewish question par excellence, it’s also, as we’ve seen, the standard question of any number of classical jokes. So isn’t that telling? The joke we told earlier, for example, about how to tell the difference between a Jew and an anti-Semite ...

The anti-Semite thinks the Jews are a despicable race, but Cohen? He’s not too bad actually. Kushner? A stand-up guy. The Jew, on the other hand, believes his people are a light unto the nations, but Cohen? What a shmuck! Kushner? Don’t get me started!

... is a joke that gains its humour from the fact that this difference turns out to be a surprisingly subtle one. Yet it’s precisely the seeming smallness of the difference that shows us why the joke is Jewish rather than anti-Semitic. For while the anti-Semite may imagine that categories and people are so completely opposed that they have nothing whatsoever to do with each other, the Jewish joke understands that every self is fractured and run through with otherness. Everyone is split by something unassimilable or strange: the sense of difference within that puts each of us in an eternal double act with all others, including those others posing as ourselves. Consider, for instance, the words of Groucho Marx’s Captain Spaulding in the film Animal Crackers (1930):

Spaulding: Say, I used to know a fellow looked exactly like you, by the name of ... ah ... Emanuel Ravelli. Are you his brother?

Ravelli: I’m Emanuel Ravelli.

Spaulding: You’re Emanuel Ravelli?

Ravelli: I’m Emanuel Ravelli.

Spaulding: Well, no wonder you look like him ... But I still insist, there is a resemblance.

What Jewish jokes consistently reveal is much the same: there’s always some sort of doubleness at play in Jewish identity, just as there is in joking itself, or in language itself. And it’s this doubleness that makes even the truth a kind of lie (‘You say you’re going to Minsk and I happen to know you really are going to Minsk, so why are you lying to me?’), which is probably what’s so funny about the truth – the reason why it tickles us.

So what, then, is the difference between a Jewish person and a comedian? Is it simply a question of distinguishing the funny peculiar from the funny ha ha? Or might it be that those two types of funny are as inseparable from each other as are Laurel and Hardy, Laverne and Shirley,* or any other shlemiel/ shlimazel comedy double act? Besides, can we even tell if it’s the fall guy or the straight guy who we’re laughing at? What if the funny ha ha of the shlemiel’s various pratfalls is really just a cover story for exposing how funny peculiar the supposedly ‘straight guy’ is?

Even Emanuel Ravelli is only passing as Emanuel Ravelli, after all. And even those things we would most dearly like to believe are unquestionable, universal, and completely unmarked by differences, have a tendency to mislead us:

A non-Jewish maths teacher gets a job in a Jewish primary school.

‘Are you concerned at all, since you’re not Jewish yourself, about what it might be like teaching Jewish children?’ the head teacher asks him.

‘Not remotely,’ says the teacher. ‘I teach mathematics, and maths knows neither creed nor colour nor age nor gender – it’s a universal language, and that’s what makes it beautiful.’

Next day, the teacher teaches his first class. He draws a diagram on the blackboard and asks, ‘What’s two per cent?’

At which point a small boy in the front row opens out his palms, shrugs his shoulders and admits, ‘You’re right.’†

There are a great many things one could find to say about a young boy for whom mathematics is just another vernacular – a set of rules more practical than Platonic, a language of compromise, of give and take – but this joke is no more about mathematics than the joke about conversion is about Christianity, or the joke about queuing about communism. Rather, what all these Jewish jokes have in common is the conviction that universal claims, whether made in the name of religion, politics, science or even golf, always leave someone on the outside – someone who sees or hears things differently:

At Columbia University [this one’s meant to be a true anecdote] the great linguist J. L. Austin once gave a lecture about language in which he explained how many languages employ the double negative to denote a positive – ‘he is not unlike his sister’ for example. ‘But there exists no language in which the equivalent is true,’ said Austin. ‘There is no language that employs a double positive to make a negative.’ At this point the philosopher Sidney Morgenbesser, sitting at the back of the lecture theatre, could be heard audibly scoffing, ‘Yeah, yeah.’

Telling the difference, in other words, is a way of telling the truth about language – about how language is nothing but difference:

Before the war, there was a great international Esperanto convention in Geneva. Esperanto scholars came from all over the world to give papers about, and to praise the idea of, an international language. Every country on earth was represented at the convention, and all the papers were given in Esperanto. After the long meeting was finally concluded, the great scholars wandered amiably along the corridors, and at last they felt free to talk casually among themselves in their international language: ‘Nu, vos macht a yid?’

That, for those in the know, is a Yiddish ‘how do you do’. Indeed Esperanto, another modern utopian dream of a universal system – in this case the dream of a universal language – was invented by a Polish Jew, L. L. Zamenhof.‡ So what are we to make of this? That only those who’ve been forced to feel their differences would dream up such hare-brained schemes for overcoming them ...?

Possibly. And yet another Jewish philosopher, Jacques Derrida, doesn’t think differences can be overcome. In fact, for Derrida, all language tells of difference (and even the word difference is one he inflects with a subtle semantic difference, spelling it ‘différance’). Here, accordingly, is his take on another classic Jewish joke:

There are three people isolated on an island: a German citizen, a French citizen and a Jew, totally alone on this island. They don’t know when they will leave the island, and it is boring.

One of them says, ‘Well, we should do something. We should do something, the three of us. Why don’t we write something on the elephants?’ There were a number of elephants on the island. ‘Everyone should write something on the elephants and then we could compare the styles and the national idioms,’ and so on and so forth.

So the week after, the French one came, with a short, brilliant, witty essay on the sexual drive, or sexual appetite, of the elephants; very short, bright and brilliant essay, very, very superficial but very brilliant. Three months or three years after that, the German came with a heavy book on the ... let’s say a very positive scientific book on the comparison between two kinds of species, with a very scientific title, endless title for a very positive scientific book on the elephants and the ecology of the elephants on the island. And the two of them asked the Jew, ‘Well, when will you give us your book?’

‘Wait, it’s a very serious question. I need more time. I need more time.’

And they came again every year asking him for his book. Finally, after ten years, he came back with a book called ‘The Elephant and the Jewish Question’.

Faced with the Jewish question, the question of difference itself, you always need to defer the answer (Derrida’s ‘différance’ is a composite of difference and deferral). You always need more time – so much time, in fact, that the Jewish question has made something of a shaggy dog story out of Jewish history:

A young Jewish Frenchman brought his trousers to a tailor to have them altered. But by the next day France was occupied and it was too dangerous for Jews to appear in public. He hid underground. Soon enough he got involved in the Resistance. He eventually found his way to a boat and managed to escape the death camps of Europe. He settled in Israel. Ten years later he returned to France. While dressing, he reached into his jacket pocket and found the tailor’s receipt for his trousers. He went to look for the tailor’s shop and, amazingly, it was still there. He handed the tailor the receipt and asked, ‘Are my trousers here?’

‘Yes, of course,’ said the tailor. ‘Be ready next Tuesday.’

And yet the fact that the Jewish question, like the Jewish joke, endures, finding itself constantly repeated and recycled, as if no change in time or place or polity could make the blindest bit of difference, is also cause for a very Jewish kind of optimism:

On the eve of the Day of Atonement, when all Jews are asked to seek forgiveness, two Jews who hate one another see each other in shul.

One approaches the other and says, ‘I wish for you everything that you wish for me.’

The other replies, ‘Already, you’re starting again?’

Never forget the Dropkin fart! For it’s a joke to imagine the slate can be so easily wiped clean, just as it’s a folly to presume that hostilities can be easily upended or differences simply overcome. And Jewish jokes all pay homage to such a world: a world that’s complicated, non-homogeneous and full of irreconcilable differences.§ But yeah, yeah, who says repetition doesn’t make a difference? For though he may well have given up all hope of reconciliation because he finds his rival unbearable, each man in the Yom Kippur joke does briefly bear with the other man. And isn’t it precisely that bearable/unbearable coming together in an intimate space, where one doesn’t deny one’s contradictions, confusions and differences, the dynamic that’s at play in every good joke?

Just as tickling isn’t stroking, laughter has something of aggression in it. But given the capacity of the funny to sustain differences, contradictions and uncertainties rather than seeking their obliteration, it’s generally a better way of dealing with aggression than the alternatives. Thus, if Jews have, at certain points in their history, developed a particular appreciation for the funny side, it’s likely because they’ve needed to mitigate the terrors of a world in which differences are no longer tolerated.¶ One need only look at the fate of ‘the Jewish question’ for example. The questions faced by post-Enlightenment Jews – ‘What is the nature of your identity? What unites you as a group? What makes you different?’ – would prove so incredibly dangerous because Jews were unable to answer them in a manner that could satisfy their interrogators. What, their interrogators wanted to know, were they hiding? After all, nothing provokes aggression like the feeling that those one finds funny (peculiar) must be sharing some sort of secret joke with each other (ha ha). And there’s little worse than the thought that other people may be secretly or not so secretly laughing at us.

So it is that Jewish comedians have tended to cover their own backs with self-deprecation – because they get how nervous laughter is. Indeed, if Don DeLillo’s Lenny Bruce inspires increasingly nervous laughs by saying ‘We’re all gonna die!’ over and over again, the rabbi turned stand-up comedian Jackie Mason has been able to elicit equally manic laughter from his audiences by saying just one word over and over again:

Jew. Jew. Jew. Jew. Jew.

Clearly there isn’t, for Mason, all that much of a difference between a Jew and a joke. Not when it’s possible to pare down his act to this one lonely word, saying it over and over until the whole room is in hysterics. Or, rather, all the Jews are laughing, and all the non-Jews are wondering what the hell the Jews are laughing about (‘Hmmm, I always knew there was something funny about those peculiar people’).

But why is the word Jew sometimes funny? For if the same ‘joke’ were told by a non-Jew, wouldn’t a very different kind of audience be cracking up at it? The word or the joke would be exactly the same, but wouldn’t that comedy now be a kind of hate speech? So who gets to decide that the word Jew is or isn’t a joke? And how can you tell the difference between this joke when it’s told by a Jewish comedian or an anti-Semitic one?

What about when the (partly Jewish, though mostly lapsed Catholic) comedian Louis C.K. tells it for example - a comic who, as we mentioned before, is no stranger to causing offense? ‘Jew,’ C.K. notes in one of his sets, is ‘the only word that is the polite thing to call a group of people and the slur for the same group ... It’s the same word, just with a little stank on it, and it becomes a terrible thing to call a person.’ So not unlike Mason, and to similarly irrepressible laughter, C.K. has also tried out the good and the bad ‘Jew’ on audiences:

Jew. Jew. Jew. Jew. Jew.

Though it’s precisely because he enunciates it both ways that we needn’t presume that his Jewish joke is an anti-Semitic one.

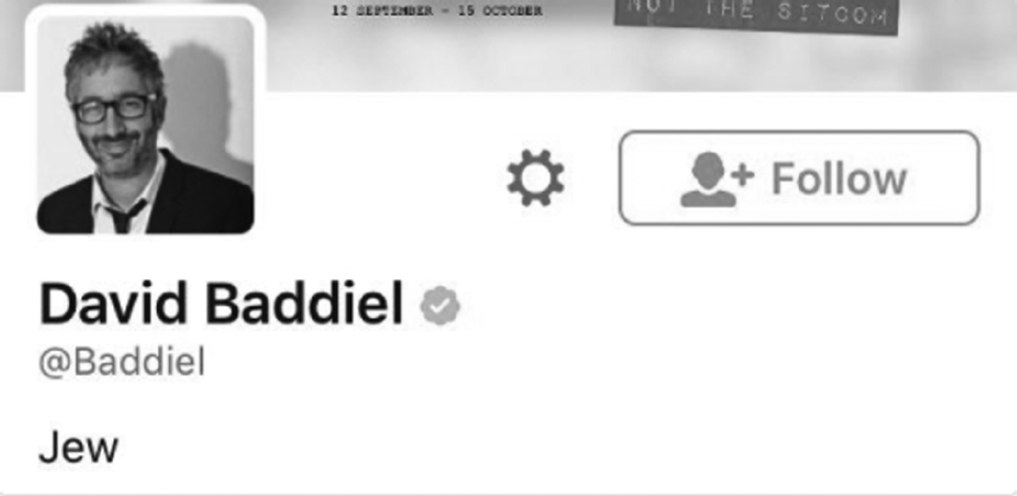

However for me the most perfect illustration of this same Jewish ‘joke’ comes to us via the Twitter account of a British comedian, David Baddiel, whose profile identifies him quite simply:

And that seeming banality has the odd effect of functioning like a kind of Rorschach test for the online hoards: at once literal and confounding, it manages somehow to troll the trolls even before they’ve arrived at the scene. Indeed, Twitter profiles don’t get much funnier. Thus, in his stand-up show My Family: Not the Sitcom (2016), Baddiel elicits roars of appreciative laughter from his audience when he projects an image of his Twitter by-line onto a large screen. No need, in other words, to follow convention and name his profession as a ‘comedian’ – by naming himself ‘Jew’ we can already tell he’s a comedian. So it is that Jews, as another British comic, Sacha Baron Cohen, confirms, ‘have a tendency to become comedians.’

To help us decipher this brainteaser, whereby the same word is both a joke and not a joke, both a cordiality and a slur, we might try telling the difference between the Jewish ‘Jew’ and the anti-Semitic ‘Jew’ this way: whereas an anti-Semite purports to know exactly what they mean when they say the word Jew, always with the intention of provoking derision or laughter, Jews couldn’t tell you what Jew means, they just know it’s funny. And what Jews find particularly funny about it is linked to the assumption that they must have some sort of insider’s knowledge as to why it’s funny. It’s the notion that they know what the difference is that gets them rolling in the aisles. Because they haven’t a clue! Thus knowing that you don’t know what Jewish means is what makes you Jew-ish, just as the repeated discovery of what you consistently fail to know – especially when it’s something you technically do: ‘We’re all gonna die!’ – is unfailing fodder for the enduring joke. The ha ha may make us laugh, in other words, but it’s the peculiar that makes us hysterical. Or, as the novelist Saul Bellow once put it:

In Jewish stories laughter and trembling are so curiously intermingled that it is not easy to determine the relation of the two.#

Such a curious intermingling is bound to make for a lot of nervous laughs, lol. But that’s not the whole of it. Failing to tell the difference between laughter and trembling also makes for something else: the shuddering sound of a laughter that, at certain points in life and history, does not quite tell its difference from a prayer.

PUNCHLINE

Oy vey! Look who thinks she knows she knows nothing.

* Laverne and Shirley were the female co-stars of an American sitcom in the late 1970s to early 1980s, whose theme song opened, ‘One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, shlemiel, shlimazel ...’

† Most jokes are best heard aloud, but this one especially.

‡ He was also responsible for writing the first published grammar of Yiddish.

§ Which is why the mainstreaming of Jewish humour in America especially should not be read as a trend towards universalising the joke, but should rather be understood the other way round: as a sign that more and more people may be feeling themselves outsiders.

¶ Of course, there are plenty of Jews who neither joke nor get tickled by jokes. Such humourlessness merits its own historical explanation. It’s not my purpose here to suggest one, but I will briefly draw attention to two different types of humourlessness hinted at in David Grossman’s unfunny book about a comedian. One of these is fair game for the caustic stand-up: ‘Have you ever seen a lefty laugh? ... they just can’t see the humour in the situation.’ You can poke fun at lefties, in other words, for their sententiousness, for their political correctness and for their implicit bad faith. But the novel also features a less partisan example: a disturbingly child-like looking older member of the audience who is always in earnest and who functions as a kind of conscience for the stand-up who will show no mercy to anyone except for this ‘tiny woman’ whom he dimly recalls from his own childhood as the other troubled kid on the block to become an object of derision and general punch-bag, but who never learned, as he did, to take on that sadism and use it as a tool of survival in a harsh and pitiless world.

# Saul Bellow’s essay ‘On Jewish storytelling’ appears in Hana Wirth-Nesher (ed.), What is Jewish Literature? (1994).