Chapter 4

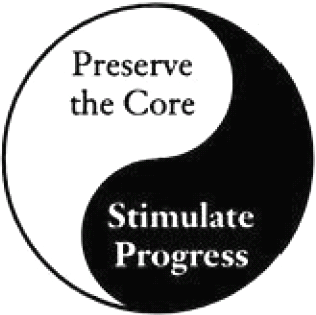

Preserve the Core/Stimulate Progress

Paul Galvin urged us to keep moving forward, to be in motion for motion’s sake... He urged continuous renewal... Change unto itself is essential. But, taken alone: it is limited. Yes, renewal is change. It calls for “do differently.” It is willing to replace and redo. But it also cherishes the proven basics.1

ROBERT W. GALVIN, FORMER CEO, MOTOROLA, 1991

It is the consistency of principle ... that gives us direction... [Certain principles] have been characteristics of P&G ever since our founding in 1837. While Procter & Gamble is oriented to progress and growth, it is vital that employees understand that the company is not only concerned with results, but how the results are obtained.2

ED HARNESS, FORMER PRESIDENT, PROCTER & GAMBLE, 1971

In the previous chapter, we presented core ideology as an essential component of a visionary company. But core ideology alone, as important as it is, does not—indeed cannot—make a visionary company. A company can have the world’s most deeply cherished and meaningful core ideology, but if it just sits still or refuses to change, the world will pass it by. As Sam Walton pointed out: “You can’t just keep doing what works one time, because everything around you is always changing. To succeed, you have to stay out in front of that change.”3 Similarly, Thomas J. Watson, Jr., embedded a huge caveat in his booklet A Business and Its Beliefs:

If an organization is to meet the challenges of a changing world, it must be prepared to change everything about itself except [its basic] beliefs as it moves through corporate life.... The only sacred cow in an organization should be its basic philosophy of doing business. [emphasis ours]4

We believe IBM began to lose its stature as a visionary company in the late 1980s and early 1990s in part because it lost sight of Watson’s incisive caveat. Nowhere in IBM’s “three basic beliefs”* do we see anything about white shirts, blue suits, specific policies, specific procedures, organizational hierarchies, mainframe computers—or computers at all, for that matter. Blue suits and white shirts are not core values. Mainframe computers are not core values. Specific policies, procedures, and practices are not core values. IBM should have much more vigorously changed everything about itself except its core values. Instead, it stuck too long to strategic and operating practices and cultural manifestations of the core values.

We’ve found that companies get into trouble by confusing core ideology with specific, noncore practices. By confusing core ideology with noncore practices, companies can cling too long to noncore items—things that should be changed in order for the company to adapt and move forward. This brings us to a crucial point: A visionary company carefully preserves and protects its core ideology, yet all the specific manifestations of its core ideology must be open for change and evolution. For example:

• HP’s “Respect and concern for individual employees” is a permanent, unchanging part of its core ideology; serving fruit and doughnuts to all employees at ten A.M. each day is a noncore practice that can change.

• Wal-Mart’s “Exceed customer expectations” is a permanent, unchanging part of its core ideology; customer greeters at the front door is a noncore practice that can change.

• Boeing’s “Being on the leading edge of aviation; being pioneers” is a permanent, unchanging part of its core ideology; commitment to building jumbo jets is part of a noncore strategy that can change.

• 3M’s “Respect for individual initiative” is a permanent, unchanging part of its core ideology; the 15 percent rule (where technical employees can spend 15 percent of their time on projects of their choosing) is a noncore practice that can change.

• Nordstrom’s “Service to the customer above all else” is a permanent, unchanging part of its core ideology; regional geographic focus, piano players in the lobby, and overstocked inventory management are non-core practices that can change.

• Merck’s “We are in the business of preserving and improving human life” is a permanent, unchanging part of its core ideology; its commitment to research targeted at specific diseases is part of a noncore strategy that can change.

It is absolutely essential to not confuse core ideology with culture, strategy, tactics, operations, policies, or other noncore practices. Over time, cultural norms must change; strategy must change; product lines must change; goals must change; competencies must change; administrative policies must change; organization structure must change; reward systems must change. Ultimately, the only thing a company should not change over time is its core ideology—that is, if it wants to be a visionary company.

This brings us to the central concept of this book: the underlying dynamic of “Preserve the core and stimulate progress” that’s the essence of a visionary company. This is a brief chapter to introduce this fundamental concept and to present an organizing framework that provides a backdrop for the dozens of detailed stories and specific examples that fill the remaining six chapters.

DRIVE FOR PROGRESS

Core ideology in a visionary company works hand in hand with a relentless drive for progress that impels change and forward movement in all that is not part of the core ideology. The drive for progress arises from a deep human urge—to explore, to create, to discover, to achieve, to change, to improve. The drive for progress is not a sterile, intellectual recognition that “progress is healthy in a changing world” or that “healthy organizations should change and improve” or that “we should have goals”; rather, it’s a deep, inner, compulsive—almost primal—drive.

It is the type of drive that led Sam Walton to spend time during the last precious few days of his life discussing sales figures for the week with a local store manager who dropped by his hospital room—a drive shared by J. Willard Marriott, who lived by the motto “Keep on being constructive, and doing constructive things, until it’s time to die ... make every day count, to the very end.”5

It is the drive that motivated Citicorp to set the goal to become the most pervasive financial institution in the world when it was still small enough that such an audacious goal would seem ludicrous, if not foolhardy. It is the type of drive that led Walt Disney to bet its reputation on Disneyland with no market data to indicate demand for such a wild dream. It is the type of drive that impelled Ford to stake its future on the audacious goal “to democratize the automobile” and thereby leave an indelible imprint on the world.

It is the type of drive that spurred Motorola to live by the motto “Be in motion for motion’s sake!” and propelled the company from battery eliminators and car radios to televisions, microprocessors, cellular communications, satellites circling the earth, and pursuit of the daunting “six sigma” quality standard (only 3.4 defects per million). Robert Galvin used the term “renewal” to describe Motorola’s inner drive for progress:

Renewal is the driving thrust of this company. Literally the day after my father founded the company to produce B Battery Eliminators in 1928, he had to commence the search for a replacement product because the Eliminator was predictably obsolete in 1930. He never stopped renewing. Nor have we.... Only those incultured with an elusive idea of renewal, which obliges a proliferation of new, creative ideas ... and an unstinting dedication to committing to the risk and promise of those unchartable ideas, will thrive.6

It is the drive for progress that pushed 3M to continually experiment and solve problems that other companies had not yet even recognized as problems, resulting in such pervasive innovations as waterproof sandpaper, Scotch tape, and Post-it notes. It compelled Procter & Gamble to adopt profit-sharing and stock ownership programs in the 1880s, long before such steps became fashionable, and urged Sony to prove it possible to commercialize transistor-based products in the early 1950s, when no other companies had done so. It is the drive that led Boeing to undertake some of the boldest gambles in business history, including the decision to build the B-747 in spite of highly uncertain market demand—a drive articulated by William E. Boeing during the early days, of the company:

It behooves no-one to dismiss any novel idea with the statement that it “can’t be done.” Our job is to keep everlastingly at research and experiment, to adapt our laboratories to production as soon as practicable, to let no new improvement in flying and flying equipment pass us by.7

Indeed, the drive for progress is never satisfied with the status quo, even when the status quo is working well. Like a persistent and incurable itch, the drive for progress in a highly visionary company can never be satisfied under any conditions, even if the company succeeds enormously: “We can always do better; we can always go further; we can always find new possibilities.” As Henry Ford said, “You have got to keep doing and going.”8

An Internal Drive

Like core ideology, the drive for progress is an internal force. The drive for progress doesn’t wait for the external world to say “It’s time to change” or “It’s time to improve” or “It’s time to invent something new.” No, like the drive inside a great artist or prolific inventor, it is simply there, pushing outward and onward. You don’t create Disneyland, build the 747, pursue six-sigma quality, invent 3M Post-it notes, institute employee stock ownership in the 1880s, or meet with a store manager on your deathbed because the outside environment demands it. These things arise out of an inner urge for progress. In a visionary company, the drive to go further, to do better, to create new possibilities needs no external justification.

Through the drive for progress, a highly visionary company displays a powerful mix of self-confidence combined with self-criticism. Self-confidence allows a visionary company to set audacious goals and make bold and daring moves, sometimes flying in the face of industry conventional wisdom or strategic prudence; it simply never occurs to a highly visionary company that it can’t beat the odds, achieve great things, and become something truly extraordinary. Self-criticism, on the other hand, pushes for self-induced change and improvement before the outside world imposes the need for change and improvement; a visionary company thereby becomes its own harshest critic. As such, the drive for progress pushes from within for continual change and forward movement in everything that is not part of the core ideology.

Notice the ruthless self-imposed discipline captured in Bruce Nordstrom’s response to the adulation the company had attained for its customer service standards: “We don’t want to talk about our service. We’re not as good as our reputation. It is a very fragile thing. You just have to do it every time, every day.”9 Notice the inner drive described by a Hewlett-Packard marketing manager who never let his people rest on their laurels:

We’re proud of our successes, and we celebrate them. But the real excitement comes in figuring out how we can do even better in the future. It’s a never-ending process of seeing how far we can go. There’s no ultimate finish line where we can say “we’ve arrived.” I never want us to be satisfied with our success, for that’s when we’ll begin to decline.10

PRESERVE THE CORE AND STIMULATE PROGRESS

Notice the dynamic interplay between core ideology and the drive for progress:

| Core Ideology | Drive for Progress |

| Provides continuity and stability. | Urges continual change (new directions, new methods, new strategies, and so on). |

| Plants a relatively fixed stake in the ground. | Impels constant movement (toward goals, improvement, an envisioned form, and so on). |

| Limits possibilities and directions for the company (to those consistent with the content of the ideology). | Expands the number and variety of possibilities that the company can consider. |

| Has clear content (“This is our core ideology and we will not breach it”). | Can be content-free (“Any progress is good, as long as it is consistent with our core”). |

| Installing a core ideology is, by its very nature, a conservative act. | Expressing the drive for progress can lead to dramatic, radical, and revolutionary change. |

The interplay between core and progress is one of the most important findings from our work. In the spirit of the “Genius of the AND,” a visionary company does not seek mere balance between core and progress; it seeks to be both highly ideological and highly progressive at the same time, all the time. Indeed, core ideology and the drive for progress exist together in a visionary company like yin and yang of Chinese dualistic philosophy; each element enables, complements, and reinforces the other:

• The core ideology enables progress by providing a base of continuity around which a visionary company can evolve, experiment, and change. By being clear about what is core (and therefore relatively fixed), a company can more easily seek variation and movement in all that is not core.

• The drive for progress enables the core ideology, for without continual change and forward movement, the company—the carrier of the core—will fall behind in an ever-changing world and cease to be strong, or perhaps even to exist.

Although the core ideology and drive for progress usually trace their roots to specific individuals, a highly visionary company institutionalizes them—weaving them into the very fabric of the organization. These elements do not exist solely as a prevailing ethos or “culture.” A highly visionary company does not simply have some vague set of intentions or passionate zeal around core and progress. To be sure, a highly visionary company does have these, but it also has concrete, tangible mechanisms to preserve the core ideology and to stimulate progress.

Walt Disney didn’t leave its core ideology up to chance; it created Disney University and required every single employee to attend “Disney Traditions” seminars. Hewlett-Packard didn’t just talk about the HP Way; it instituted a religious promote-from-within policy and translated its philosophy into the categories used for employee reviews and promotions, making it nearly impossible for anyone to become a senior executive without fitting tightly into the HP Way. Marriott didn’t just talk about its core values; it instituted rigorous employee screening mechanisms, indoctrination processes, and elaborate customer feedback loops. Nordstrom didn’t just philosophize about fanatical customer service; it created a cult of service reinforced by tangible rewards and penalties—“Nordies” who serve the customer well become well-paid heroes, and those who treat customers poorly get spit right out of the company.

Motorola didn’t just preach quality; it committed to a daunting six-sigma quality goal and pursued the Baldrige Quality Award. General Electric didn’t just pontificate about the importance of continuous technological innovation in the early 1900s; it created one of the world’s first industrial R&D laboratories. Boeing didn’t just dream about being on the leading edge of aviation; it made bold, irreversible commitments to audacious projects like the Boeing 747, in which failure could have literally killed the company. Procter & Gamble didn’t just think self-imposed progress was a good idea; it installed a structure that pitted P&G product lines in fierce competition with each other, thus using institutionalized internal competition as a powerful mechanism to stimulate progress. 3M didn’t just pay lip service to encouragement of individual initiative and innovation; it decentralized, gave researchers 15 percent of their time to pursue any project of their liking, created an internal venture capital fund, and instituted a rule that 25 percent of each division’s annual sales should come from products introduced in the previous five years.

Tangible. Concrete. Specific. Solid. Look inside a visionary company and you’ll see a ticking, bonging, humming, buzzing, whirring, clicking, clattering clock. You’ll see tangible manifestations of its core ideology and drive for progress everywhere.

INTENTIONS are all fine and good, but it is the translation of those intentions into concrete items—mechanisms with teeth—that can make the difference between becoming a visionary company or forever remaining a wannabe.

We’ve found that organizations often have great intentions and inspiring visions for themselves, but they don’t take the crucial step of translating their intentions into concrete items. Even worse, they often tolerate organization characteristics, strategies, and tactics that are misaligned with their admirable intentions, which creates confusion and cynicism. The gears and mechanisms of the ticking clock do not grind against each other but rather work in concert—in alignment with each other—to preserve the core and stimulate progress. The builders of visionary companies seek alignment in strategies, in tactics, in organization systems, in structure, in incentive systems, in building layout, in job design—in everything.

KEY CONCEPTS FOR CEOS, MANAGERS, AND ENTREPRENEURS

In working with practicing managers, we’ve found it useful to capture all of the key ideas from our findings into an overall framework that managers can use as a conceptual guide for diagnosing and designing their own organization.

Our framework, shown in Figure 4.A, has two layers. The top layer of the framework contains elements discussed in earlier chapters: a clock-building orientation (Chapter 2), the yin/yang symbol (No “Tyranny of the OR”), core ideology (Chapter 3), and the drive for progress (described earlier in this chapter). You can think of the top layer as a set of guiding intangibles that are necessary requirements to become a visionary company. However, as important as they are, these intangible elements alone are not sufficient for becoming a visionary company. To become a visionary company requires translating these intangibles down into the second layer of the framework, and this is where most companies just fail to make the grade.