Now, I want you to raise your right hand—and remember what we say at Wal-Mart, that a promise we make is a promise we keep—and I want you to repeat after me: From this day forward, I solemnly promise and declare that every time a customer comes within ten feet of me, I will smile, look him in the eye, and greet him. So help me Sam.

SAM WALTON, TO OVER ONE HUNDRED THOUSAND WAL-MART ASSOCIATES VIA TV SATELLITE LINK-UP, MID-1980S1

IBM is really good at motivating its people; I see that through Anne. [She] might be brainwashed by some people’s standards, but it’s a good brainwashing. They really do instill a loyalty and drive to work.

SPOUSE OF IBM EMPLOYEE, 19852

So why do you want to work at Nordstrom?” the interviewer asks.

“Because my friend, Laura, tells me it’s the best place she’s ever worked,” Robert responds. “She gushes about the excitement of working with the very best—being part of the elite of the elite. She’s almost a missionary for you folks. Very proud to call herself a Nordstrom employee. And she’s been rewarded well. Laura started in the stockroom eight years ago and now she gets to manage an entire store; she’s only twenty-nine.3 She told me that people here make a lot more than salespeople at other stores, and that the best salespeople working on the floor can make over $80,000 a year.”*4

“Yes, it’s true that you can make more money here than working at other department stores. Our salespeople generally make almost double the national average for retail sales clerks—and a few make a lot more than that.5 But you know, of course, not everyone has what it takes to really make it here as a member of the Nordstrom corporate family,” explains the interviewer. “We’re selective, and a lot don’t make it. You prove yourself at every level, or you leave.”6

“Yes. I’ve heard that 50 percent of new hires are gone after one year.”7

“Something like that. Those who don’t like the pressure and the hard work, and who don’t buy into our system and values, they’re gone. But if you have the drive, initiative, and—above all else—the ability to produce and serve the customer, then you’ll do well.8 The key question is whether Nordstrom is right for you. If not, you’ll probably hate it here, fail miserably, and leave.”9

“What positions would I be eligible for?”

“The same as every other new hire—you start at the bottom, working the stockroom and the sales floor.”

“But I have a bachelor’s degree, Phi Beta Kappa, from University of Washington. Other companies will let me begin as a management trainee.”

“Not here. Everybody starts at the bottom. Mr. Bruce, Mr. Jim, and Mr. John—the three Nordstrom brothers that make up the chairman’s office—they all started on the floor. Mr. Bruce likes to remind us that he and his brothers were all raised sitting on a shoe sales stool in front of the customer; it’s a literal and figurative posture that we all keep in mind.10 You get a lot of operational freedom here; no one will be directing your every move, and you’re only limited by your ability to perform (within the bounds of the Nordstrom way, of course). But if you’re not willing to do whatever it takes to make a customer happy—to personally deliver a suit to his hotel room, get down on your knees to fit a shoe, force yourself to smile when a customer is a real jerk—then you just don’t belong here, period. Nobody tells you to be a customer service hero; it’s just sort of expected.”11

Robert took the job at Nordstrom, excited at the prospect of joining something special, thrilled to be at the place to work. He was proud to receive personalized professional business cards, rather than a name tag.12 The handout depicting Nordstrom’s “Company Structure” as an upside down pyramid made him feel even more important.13

He also received a copy of Nordstrom’s employee handbook, which consisted of a single five-by-eight-inch card and read, in its entirety:14

WELCOME TO NORDSTROM

We’re glad to have you with our Company.

Our number one goal is to provide

outstanding customer service.

Set both your personal and professional goals high.

We have great confidence in your ability to achieve them.

Nordstrom Rules:

Rule #1: Use your good

judgment in all situations.

There will be no additional rules.

Please feel free to ask your department manager,

store manager or division general manager

any question at any time.

During his first few months, Robert became immersed in the world of a dedicated “Nordie,” as many employees called themselves.15 He found that he spent most of his time at the store, at Nordie functions, or socializing with other Nordies; they became his support group.16 He heard dozens of stories about heroic customer service: the Nordie who ironed a new-bought shirt for a customer who needed it for a meeting that afternoon; the Nordie who cheerfully gift wrapped products a customer bought at Macy’s; the Nordie who warmed customers’ cars in winter while the customers finished shopping; the Nordie who personally knit a shawl for an elderly customer who needed one of a special length that wouldn’t get caught in the spokes of her wheelchair; the Nordie who made a last-minute delivery of party clothes to a frantic hostess; and even the Nordie who refunded money for a set of tire chains—although Nordstrom doesn’t sell tire chains.17 He learned about the notes called “heroics” that Nordstrom salespeople wrote about each other, and that were used—along with customer letters and employee thank-you notes to customers—to determine which stores should receive monthly prizes for the best service.18

His manager explained about the all-important customer letters: “Customer letters are real important around here. You never, ever want to get a bad one; that’s a real sin. But good ones can lead you to become a ‘Customer Service All Star.’ You think Phi Beta Kappa was a big deal, but to become a Customer Service All Star, now that’s a really big deal. You get a personal handshake from one of the Nordstrom brothers, your picture goes on the wall, and you get prizes and discounts. It makes you the top of the top.19 And if you become a productivity winner, you become a Pacesetter, complete with new business cards so designated and 33 percent merchandise discounts.20 Only our very top people become Pacesetters.”

“How do I become a Pacesetter?” Robert asked.

“Simple. You set very high sales goals, and then you exceed them,”21 she explained. Then she asked, “By the way, what are your sales goals for today?”22

Sales goals. Productivity. Achievement. Robert noticed “reminders” posted on the walls in the employee back rooms: “Make a daily to do list!” or “List goals, set priorities!”23 or “Don’t let us down!” or “Be a top dog pacesetter; Go for the milk bones!”24

He learned quickly about the all important SPH (sales per hour) calculation. “If you exceed your target SPH, you’ll get a ten percent commission on net sales,” his manager explained. “If not, you’ll just get your base hourly wage rate. And if you have a high SPH, you’ll get to work more attractive hours and have better odds of being promoted. You can track your SPH on computer printouts we keep in the back office. We list all the SPHs in rank order, so you can keep track and make sure you’re not falling behind. Your SPH will also appear on your pay stub.”25

At the end of his first pay period, employees gathered around a bulletin board in the back room on which was posted a ranking of SPH by employee number; a few had dropped below a red line marked on the paper.26 Robert quickly understood that he should do all that he could to avoid falling behind. He woke up one night in a cold sweat from a vivid nightmare of walking into the back room and seeing his name at the bottom of the list. He worked furiously during the day to not be left behind by his peers.27

Soon after the first pay period, Robert noticed that one of the salespeople in his area had left work early. “Where’s John?” he asked.

“Sent home for the day . . . penalized for getting irritated with a customer,” said Bill, a fellow salesperson who had won a recent Smile Contest and thereby got his picture on the wall.28 “It’s kind of like being sent to your room without dinner. He’ll be back tomorrow, but they’ll be watching him closely for a few weeks.”29

At age twenty-six, Bill was already a five-year Nordstrom veteran, a Pacesetter, and an All Star. Bill clearly had that rare “what it takes” quality to thrive at Nordstrom. “When people shop at Nordstrom, they deserve the best attitude,” he explained. “I always have my smile, for anybody, everybody.”30 Bill dressed almost exclusively in Nordstrom clothes and, in addition to the Smile Contest, he’d also won a “Who Looks the Most Nordstrom Contest”31 the prior year. He basked in the glory of public praise one day as the store manager read aloud a letter about Bill from a satisfied customer—to the applause and cheers of fellow employees.

Bill loved his job at Nordstrom, always quick to point out, “Where else could I get paid so well and have so much autonomy? Nordstrom is one of the first places I’ve ever felt like I really belong to something special. Sure, I work really hard, but I like to work hard. No one tells me what to do, and I feel I can go as far as my dedication will take me. I feel like an entrepreneur.”32

Bill had earlier moved—along with over a hundred other Nordstrom people—from Nordstrom stores on the West Coast to one of its new store openings on the East Coast.33 “We wouldn’t want non-Nordies to open a new store, even if it’s all the way across the country,” he explained. He described the excitement of opening day: “Employees were clapping. Customers came in and they were clapping, too. There was so much energy and adrenaline flowing—it was an emotional ‘look what I’m part of’ atmosphere that made you feel really special.”34

Bill was a great Nordie role model for Robert. He told Robert about how he attended a Nordstrom motivational seminar, where he learned to write upbeat “affirmations,” which he repeated over and over to himself: “I feel proud to be a Pacesetter.” Bill had the goal of becoming a store manager, so he chanted to himself the affirmation “I enjoy being a store manager at Nordstrom . . . I enjoy being a store manager at Nordstrom . . . I enjoy being a store manager at Nordstrom.”35

Bill explained that being a Nordstrom manager would be tough and demanding. He described how store managers must publicly declare their sales goals at quarterly meetings. “Mr. John, he sometimes wears a sweater with a giant N on the front and stirs up the crowd. Then someone unveils the sales target for each store set by a secret committee. I’ve heard that those managers who set goals below those set by the secret committee get booed; those who set goals higher than the committee get cheered.”36

Bill was also a great source of information and guidance about the Nordstrom Way. “Be very careful about talking to outsiders,” Bill cautioned. “The company’s very sensitive about its privacy and likes to keep tight control on what information goes to the outside world. That comes from the very top. How we do things around here is not anybody else’s business.”37

“By the way,” Bill asked as they were closing up shop late one evening, “did you know that we had a ‘secret shopper’ in here today?”

“A what?”

“A secret shopper. That’s a Nordstrom employee who pretends to be a customer—secretly—and checks on your demeanor and service. She came by you today. I think you did fine, but watch the frown. You have a tendency to frown when you’re working hard. Just remember to smile; don’t frown. A frown can be a black mark in your file.”38

“Rule number two,” Robert thought to himself. “Don’t frown, be happy.”

Over the following six months, Robert found himself increasingly uncomfortable at Nordstrom. When he found himself at a seven A.M. department meeting with Nordies chanting “We’re number one!” and “We want to do it for Nordstrom!”39 he thought back to the opening paragraph of the write-up on Nordstrom in The Best 100 Companies to Work for in America, which said, “If you don’t like to work in a gung-ho atmosphere where people are always revved up, then this is not the place for you.”40 He found himself doing okay—never falling to the bottom of the SPH listings—but, tellingly, not great. He’d never received a handshake from Mr. Jim or Mr. John or Mr. Bruce. He had not become a Pacesetter or an All Star, and feared that he would once again frown for a secret shopper or that he might get a negative customer letter. And worst of all, he was being left behind by those who were just much more Nordstrom than he. They had the right Nordstrom stuff; he didn’t. He just didn’t fit.

Robert quit eleven months into his career at Nordstrom. A year later, however, he was thriving as a department manager at another store. “Nordstrom was a great experience, but it wasn’t for me,” he explained. “I know some of my friends are incredibly happy there; they really love it. And there’s no doubt about it—Nordstrom’s a really great company. But I fit better here.”

“EJECTED LIKE A VIRUS!”

When we began our research project, we speculated that our evidence would show the visionary companies to be great places to work (or at least better places to work than the comparison companies). However, we didn’t find this to be the case—at least not for everyone. Recall how well Bill and Laura fit and flourished at Nordstrom; for them, it was a truly great place to work. But notice how Robert just couldn’t fully buy in; for him, Nordstrom was not a great place to work. Nordstrom is only a great place to work for those truly dedicated—and well suited to—the Nordstrom way.

The same is true for many of the other visionary companies that we studied. If you’re not willing to enthusiastically adopt the HP Way, then you simply don’t belong at HP. If you’re not comfortable buying into Wal-Mart’s fanatical dedication to its customers, then you don’t belong at Wal-Mart. If you’re not willing to be “Procterized,” then you don’t belong at Procter & Gamble. If you don’t want to join in the crusade for quality (even if you happen to work in the cafeteria), then you don’t belong at Motorola and you certainly can’t become a true “Motorolan.”41 If you question the right of individuals to make their own decisions about what to buy (such as cigarettes), then you don’t belong at Philip Morris. If you’re not comfortable with the Mormon-influenced, clean-living, dedication-to-service atmosphere at Marriott, then you’d better stay away. If you can’t embrace the idea of “wholesomeness” and “magic” and “Pixie dust,” and make yourself into a “clean-cut zealot,”42 then you’d probably hate working at Disneyland.

We learned that you don’t need to create a “soft” or “comfortable” environment to build a visionary company. We found that the visionary companies tend to be more demanding of their people than other companies, both in terms of performance and congruence with the ideology.

“VISIONARY,” we learned, does not mean soft and undisciplined. Quite the contrary. Because the visionary companies have such clarity about who they are, what they’re all about, and what they’re trying to achieve, they tend to not have much room for people unwilling or unsuited to their demanding standards.

During a research team meeting, one of our research assistants made the observation, “Joining these companies reminds me of joining an extremely tight-knit group or society. And if you don’t fit, you’d better not join. If you’re willing to really buy in and dedicate yourself to what the company stands for, then you’ll be very satisfied and productive—probably couldn’t be happier. If not, however, you’ll probably flounder, feel miserable and out-of-place, and eventually leave—ejected like a virus. It’s binary: You’re either in or you’re out, and there seems to be no middle ground. It’s almost cult-like.”

The observation rang true enough that we decided to examine the literature on cults and see if the visionary companies have indeed had more characteristics in common with cults than the comparison companies. We found no universally accepted definition of cult in the literature; the most common definition is that a cult is a body of persons characterized by great or excessive devotion to some person, idea, or thing (which certainly describes many of the visionary companies). Nor did we find any universally accepted checklist of what separates cults from noncults. We did, however, find some common themes, and in particular we found four common characteristics of cults that the visionary companies display to a greater degree than the comparison companies.43

• Fervently held ideology (discussed earlier in our chapter on core ideology)

• Indoctrination

• Tightness of fit

• Elitism

Look at Nordstrom versus Melville. Notice the heavy-duty indoctrination processes at Nordstrom, beginning with the interview and continuing with Nordie customer service heroic stories, reminders on the walls, chanting affirmations, and cheering. Notice how Nordstrom gets its employees to write heroic stories about other employees and engages peers and immediate supervisors in the indoctrination process. (A common practice of cults is to actively engage recruits in the socializing of others into the cult.) Notice how the company seeks to hire young people, mold them into the Nordstrom way from early in their careers, and promote only those who closely reflect the core ideology. Notice how Nordstrom imposes a severe tightness of fit—employees that fit the Nordstrom way receive lots of positive reinforcement (pay, awards, recognition)—and those who don’t fit get negative reinforcement (being “left behind,” penalties, black marks). Notice how Nordstrom draws clear boundaries between who is “inside” and who is “outside” the organization, and how it portrays being “inside” as being part of something special and elite—again, a common practice of cults. Indeed, the very term “Nordie” has a cultish feel to it. We found no evidence that Melville cultivated and maintained through its history anywhere near such clear and consistent use of practices like these.

Nordstrom presents an excellent example of what we came to call “cultism”—a series of practices that create an almost cult-like environment around the core ideology in highly visionary companies. These practices tend to vigorously screen out those who do not fit with the ideology (either before hiring or early in their careers). They also instill an intense sense of loyalty and influence the behavior of those remaining inside the company to be congruent with the core ideology, consistent over time, and carried out zealously.

Please don’t misunderstand our point here. We’re not saying that visionary companies are cults. We’re saying that they are more cult-like, without actually being cults. The terms “cultism” and “cult-like” can conjure up a variety of negative images and connotations; they are much stronger words than “culture.” But to merely say that visionary companies have a culture tells us nothing new or interesting. All companies have a culture! We observed something much stronger than just “culture” at work. “Cultism” and “cult-like” are descriptive—not pejorative or prescriptive—terms to capture a set of practices that we saw more consistently in the visionary companies than the comparison companies. We’re saying that these characteristics play a key role in preserving the core ideology.

An analysis of the visionary versus comparison companies revealed the following (see Table A.6 in the Appendix 3):

• In eleven out of eighteen pairs, the evidence shows stronger indoctrination into a core ideology through the history of the visionary company than the comparison company.*

• In thirteen out of eighteen pairs, the evidence shows greater tightness of fit through the history of the visionary company than in the comparison company—people tend to either fit well with the company and its ideology or tend to not fit at all (“buy in or get out”).

• In thirteen out of eighteen pairs, the evidence shows greater elitism (a sense of belonging to something special and superior) through the history of the visionary company.

• Summing up across all three dimensions (indoctrination, tightness of fit, and elitism), the visionary companies have shown greater cultism through history than the comparison companies in fourteen out of eighteen pairs (four pairs are indistinguishable).

The following three examples—IBM, Disney, and Procter & Gamble—show these characteristics at work in the development of visionary companies.

IBM’S RISE TO GREATNESS

Thomas J. Watson, Jr., former IBM chief executive, described the environment at IBM during its rise to national prominence in the first half of the twentieth century as a “cult-like atmosphere.”44 This atmosphere traces back to 1914, when Watson’s father (Thomas J. Watson, Sr.) became chief executive of the small, struggling company, and consciously set about to create an organization of dedicated zealots.* Watson plastered the wall with slogans: “Time lost is time gone forever”; “There is no such thing as standing still”; “We must never feel satisfied”; “We sell service”; “A company is known by the men it keeps.” He instituted strict rules of personal conduct—he required salespeople to be well groomed and wear dark business suits, encouraged marriage (married people, in his view, worked harder and were more loyal because they had to provide for a family), discouraged smoking, and forbade alcohol. He instituted training programs to systematically indoctrinate new hires into the corporate philosophy, sought to hire young and impressionable people, and adhered to a strict promote-from-within practice. Later, he created IBM-managed country clubs to encourage IBMers to socialize primarily with other IBMers, not the outside world.45

Similar to Nordstrom, IBM sought to create a heroic mythology about employees who best exemplified the corporate ideology and placed their names and pictures—along with stories of their heroic deeds—in company publications. A few exemplars even had corporate songs composed in their honor!46 And, also like Nordstrom, IBM emphasized the importance of individual effort and initiative within the context of the collective effort.

By the 1930s, IBM had fully institutionalized its indoctrination process and created a full-fledged “schoolhouse” that it used to socialize and train future officers of the company. In Father, Son & Co., Watson, Jr., wrote:

Everything about the school was meant to inspire loyalty, enthusiasm, and high ideals, which IBM held out as the way to achieve success. The front door had [IBM’s ubiquitous] motto “THINK” written over it in two foot high letters. Just inside was a granite staircase that was supposed to put students in an aspiring frame of mind as they stepped up to the day’s classes.47

Veteran employees in “regulation IBM clothes” taught the classes and emphasized IBM values. Each morning, surrounded by posters with corporate mottos and slogans, students would rise and sing IBM songs out of the songbook Songs of the IBM, which included “The Star-Spangled Banner” and, on the facing page, IBM’s own anthem, “Ever Onward.”48 IBMers sang such lyrics as:49

March on with I.B.M.

Work hand in hand,

Stout hearted men go forth,

In every land.

Although IBM eventually evolved beyond singing corporate songs, it retained its intensely values-oriented training and socialization processes. Newly hired IBMers always learned the “three basic beliefs” (described in an earlier chapter) and experienced training classes that emphasized company philosophy as well as skills. IBMers learned language unique to the culture (“IBM-speak”) and were expected at all times to display IBM professionalism. In 1979, IBM completed a twenty-six-acre “Management Development Center” that, in IBM’s own words, “might pass for a monastic retreat—until you find yourself in its busy classrooms.”50

IBM’s profile in the 1985 edition of The 100 Best Companies to Work For described IBM as a company that “has institutionalized its beliefs the way a church does. . . . The result is a company filled with ardent believers. (If you’re not ardent, you may not be comfortable.). . . Some have compared joining IBM with joining a religious order or going into the military. . . . If you understand the Marines, you understand IBM. . . . You must be willing to give up some of your individual identity to survive.”51 A 1982 Wall Street Journal article noted that the IBM culture “is so pervasive that, as one nine-year [former] employee put it, ‘leaving the company was like emigrating.’”52

Indeed, throughout its history (at least to the time of this book), IBM imposed a severe tightness of fit with its ideology. Former IBM marketing vice president Buck Rodgers explained in his book The IBM Way:

IBM begins imbuing its employees with its . . . philosophy even before they’re hired, at the very first interview. To some, the word “imbuing” connotes brainwashing, but I don’t think there’s anything negative . . . in what is done. Basically, anyone who wants to work for IBM is told: “Look this is how we do business. . . . We have some very specific ideas about what that means—and if you work for us we’ll teach you how to treat customers. If our attitude about customers and service is incompatible with yours, we’ll part ways—and the quicker the better.”53

Elitism also ran throughout the entire history of the company. Beginning in 1914, long before the company had any national stature, Watson, Sr., sought to instill the perspective that the company was a superior and special place to work. “You cannot be a success in any business,” he exhorted, “without believing that it is the greatest business in the world.”54 (And recall from the BHAG chapter how he tangibly buttressed this elitist attitude by changing the name of the company from the dreary-sounding Computer Tabulating Recording Company to The International Business Machines Corporation.) In 1989, three-quarters of a century after Watson, Sr., initiated the company’s self-concept as something elite and special, Watson, Jr., came full circle to the same theme in an essay for a seventy-fifth anniversary publication entitled IBM: A Special Company:

If we believe that we’re working for just another company, then we’re going to be like another company. We have got to have a concept that IBM is special. Once you get that concept, it’s very easy to give the amount of drive to work toward making it continue to be true.55

You might be wondering whether IBM’s cult-like atmosphere and tight adherence to its three basic beliefs contributed to IBM’s difficulties in the early 1990s. Was cultism a primary cause of IBM’s difficulty to adapt to the dramatic changes in the computer industry? Upon close inspection, the evidence does not support this view. IBM was strongly cult-like in the 1920s, yet was able to adapt to the dramatic shift to automated accounting procedures. IBM was incredibly cult-like in the 1930s, yet was able to adapt to the demands of the Depression without a single layoff. IBM maintained its cult-like culture in the 1950s and 1960s, yet was able to adapt to the rise of computers, perhaps the most dramatic shift in IBM’s history. IBM still had a cultish feel in the early 1980s, yet—unlike any other old-line computer company—adapted to the personal computer revolution and established itself as a major player. If anything, IBM’s cult-like culture—its fanatical preservation of its core values—declined as the company headed toward trouble.

IBM attained its greatest success—and displayed its greatest ability to adapt to a changing world—during the same era that it displayed its strongest cult-like culture.

Furthermore, Burroughs (IBM’s comparison) displayed little of the cultism we saw in the history of IBM. It had no Burroughs indoctrination center to “imbue” employees with corporate values. We found no indication that Burroughs sought to impose severe tightness of fit around a central ideology, nor did we see any evidence that Burroughs saw itself as elite and special in the scheme of American enterprise. IBM gave itself a clear self-identity, however cult-like. Burroughs did not. And IBM consistently pulled ahead of Burroughs at critical junctures in the evolution of the industry, even though Burroughs had a better early start in life.

THE MAGIC OF WALT DISNEY

Like IBM and Nordstrom, the Walt Disney Company has made extensive use of indoctrination, tightness of fit, and elitism as key parts of preserving its core ideology.

Disney requires every single employee—no matter what level or position—to attend new employee orientation (also known as “Disney Traditions”) taught by the faculty of Disney University, the company’s own internal socialization and training organization.56 Disney designed the course so that “new members of the Disney team can be introduced to our traditions, philosophies, organization, and the way we do business.”57

Disney pays particular attention to thoroughly screen and socialize hourly workers into its theme parks. Potential recruits—even those being hired to sweep the floor—must pass at least two screenings by different interviewers.58 (In the 1960s, Disney required all applicants to take an extensive personality test.)59 Men with facial hair and women with dangling earrings or heavy makeup need not apply; Disney enforces a strict grooming code.60 (In 1991, members of the Disneyland staff went on strike to protest the grooming code; Disney fired the strike leader and kept the rule intact.)61 Even as far back as the 1960s, Disneyland imposed strict tightness-of-fit guidelines in hiring, as Richard Schickel described park employees in his 1967 book The Disney Version:

[They] present a rather standardized appearance. The girls are generally blonde, blue-eyed and self-effacing, all looking as if they stepped out of an ad for California sportswear and are heading for suburban motherhood. The boys . . . are outdoorsy, All-American types, the kind of vacuously pleasant lad your mother was always telling you to imitate.62

All new hires at Disneyland experience a multiday training program where they quickly learn a new language:

Employees are “cast members.”

Customers are “guests.”

A crowd is an “audience.”

A work shift is a “performance.”

A job is a “part.”

A job description is a “script.”

A uniform is a “costume.”

The personnel department is “casting.”

Being on duty is “onstage.”

Being off duty is “backstage.”

The special language reinforces the frame of mind Disney imposes via carefully scripted orientation seminars delivered by well-practiced “trainers” who drill new cast members with questions about Disney characters, history, and mythology, and who constantly reinforce the underlying ideology:

TRAINER: What business are we in? Everybody knows McDonald’s makes hamburgers. What does Disney make?

NEW HIRE: It makes people happy.

TRAINER: Yes, exactly! It makes people happy. It doesn’t matter who they are, what language they speak, what they do, where they come from, what color they are, or anything else. We’re here to make ’em happy. . . . Nobody’s been hired for a job. Everybody’s been cast for a role in our show.63

The orientation seminars take place in specially designed training rooms, plastered with pictures of founder Walt Disney and his most famous characters (such as Mickey Mouse, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs). They aim, in the words of a Tom Peters Group video, “to create the illusion that Walt himself is present in the room, welcoming the new hires to his personal domain. The object is to make these new employees feel like partners with the Park’s founder.”64 Employees read from the University Textbooks, which have included such exhortations as: “At Disneyland we get tired, but never bored, and even if it’s a rough day, we appear happy. You’ve got to have an honest smile. It’s got to come from within. . . . If nothing else helps, remember that you get paid for smiling.”65

After in-class orientation, each new cast member doubles up with an experienced peer who further socializes him or her into the nuances of the specific job. Throughout, Disney enforces strict codes of behavior and conduct, demanding that the cast member quickly sand off any personality quirks that do not fit their specific script.66 Training magazine observed: “At Disney there is no such thing as an unplanned moment for new hires. The first days following the Disney orientation program are filled with costume (uniform) fittings, script rehearsals (training) and meeting fellow cast members. And it is all as carefully orchestrated and thought-out as any performance staged for theme park guests.”67

Disney’s fanatical preservation of its self-image and ideology has shown itself most clearly in the theme parks, but it also extends far beyond the theme parks. All employees in the company must attend a Disney Traditions orientation seminar. A Stanford MBA who spent a summer at Disney doing financial analysis, strategic planning, and other similar work, described:

I recognized the magic of Walt’s vision on my first day at the Walt Disney Company. . . . At Disney University, through videos and “pixie dust,” Walt shared his dreams and the magic of Disney’s “world.” Disney archives treasure Walt’s history for cast members to enjoy. After orientation, I stopped at the corner of Mickey Avenue and Dopey Drive—I felt the magic, the sentimentality, the history. I believed in Walt’s dream and shared this belief with others in the organization.68

No employee anywhere in the company could cynically or flagrantly denounce the ideal of “wholesomeness” and survive.69 Company publications constantly emphasize that Disney is “special,” “different,” “unique,” “magical.” Even the company’s annual reports to shareholders have been peppered with such terms and phrases as “dreams,” “fun,” “excitement,” “joy,” “imagination,” and “magic is the essence of Disney.”70

Disney shrouds much of its inner workings in secrecy, which further contributes to a sense of mystery and elitism—only those deep on the “inside” get to peek behind the curtain to see the mechanics of the “magic.” No one except specific cast members (who are sworn to secrecy), for example, can observe the training of characters at Disneyland. Writers who cover Disney have encountered fiercely protective gatekeepers to the secrets of the Magic Kingdom. “Disney is a strangely closed corporation,” wrote one author. “It [has] a level of controlling paranoia I had never encountered in my years of writing about American business.”71

Disney’s intensive screening and indoctrination of employees, its obsession with secrecy and control, and its careful cultivation of a mythology and image as something special—and important—to the lives of children around the world, all help to create a cultish following that extends even to its customers. A loyal Disney customer once noticed a slightly discolored Disney character doll at a retail store and seethed, “If Uncle Walt saw that, he’d be ashamed.”72

Indeed, when examining Disney, it can be hard to keep in mind that it is a corporation, not a social or religious movement. Joe Fowler wrote in his book Prince of the Magic Kingdom:

This is not a corporate history. It is a history of a deeply human struggle over ideas, values, and hopes for which men and women were willing to give themselves over, values at times so evanescent that some people could dismiss them as silly, values so deep that others became students of them, dedicated their careers to making them come alive, became enraged and embittered when they seemed to be violated, and turned poetic and inspired in their defense. This is what is impressive about the name “Disney”: no one is neutral. . . . Walt Disney was a genius or a charlatan, a hypocrite or an exemplar, a snake-oil salesman or a beloved father figure to generations of children.73

The company’s cult-like culture does, in fact, trace to founder Walt Disney, who saw the relationship between himself and employees as like that between father and children.74 He expected complete dedication from Disney employees, and he demanded unblemished loyalty to the company and its values. A dedicated and—above all—loyal Disneyite could make honest mistakes and be given a second (and often, third, fourth, and fifth) chance.75 But to breach the sacred ideology or to display disloyalty. . . well, these were sins, punishable by immediate and unceremonious termination. According to Marc Eliot’s biography Walt Disney, “When someone did, on occasion, slip in Walt’s presence and use a four-letter word in mixed company, the result was always immediate dismissal, no matter what type of professional inconvenience the firing caused.”76 When Disney animators went on strike in 1941, Walt felt betrayed by his workers and saw the union not so much as an economic force but as an intrusion into his carefully controlled “family” of loyal Disneyites.77

Walt had a rage for order and control that he translated into tangible practices to maintain the essence of Disney. The personal grooming code, the recruiting and training processes, the fanatical attention to the tiniest details of physical layout, the concern with secrecy, the exacting rules about preserving the integrity and sanctity of each Disney character—these all trace their roots to Walt’s quest to keep the Disney Company completely within the bounds of its core ideology. Walt described the roots of the Disneyland processes:

The first year I leased out the parking concession, brought in the usual security guards—things like that. But I soon realized my mistake. I couldn’t have outside help and still get over my idea of hospitality. So now we recruit and train every one of our employees. I tell the security officers, for instance, that they are never to consider themselves cops. They are there to help people. . . . Once you get the policy going, it grows.78

And grow it did. Even though the company languished after Walt’s death, it never lost its core ideology, due in large part to the tangible processes laid in place before he died. And when Michael Eisner and the New Disney Team took over in 1984, the core—carefully preserved—formed the bedrock of Disney’s resurgence in the following decade.

Columbia Pictures, in contrast, had neither a core ideology nor any core preservation mechanisms in place after Cohn’s death in 1958. Walt didn’t build a perfectly ticking clock, but he did have a core ideology, and he did clock-build mechanisms (however cultish) to preserve the core ideology. Colin did not. Disney eventually rebounded after Walt’s death as an independent institution built on his legacy; Columbia Pictures ceased to exist as an independent company.

COMPLETE IMMERSION AT PROCTER & GAMBLE

Throughout most of its history, Procter & Gamble has preserved its core ideology through extensive use of indoctrination, tightness of fit, and elitism. P&G has long-standing practices of carefully screening potential new hires, hiring young people for entry-level jobs, rigorously molding them into P&G ways of thought and behavior, spitting out the misfits, and making middle and top slots available only to loyal P&Gers who grew up inside the company. The 100 Best Companies to Work for in America states:

Competition to get into P&G is tough. . . . Recruits, when they sign on, may feel they have joined an institution, rather than a company. . . . No one ever comes into P&G at a middle or top-management level who has garnered his or her experience at another company. It just doesn’t happen. This is an up-through-the-ranks company with a vengeance.79. . . There is a P&G way of doing things, and if you don’t master it or at least feel comfortable with it, you’re not going to be happy here, not to speak of being successful.80

Indoctrination processes are both formal and informal. P&G inducts new employees into the company with training and orientation sessions and expects them to read its official biography Eyes on Tomorrow (also known to insiders as “The Book”), which describes the company as “an integral part of the nation’s history” with “a spiritual inheritance” and “unchanging character . . . that [has] remained solidly based on the principle, the ethics, the morals so often pronounced by the founders [and] has become a lasting heritage.”81 Internal company publications, talks by executives, and formal orientation materials stress P&G’s history, values, and traditions.82 Employees cannot miss seeing the “Ivorydale Memorial” overlooking the Ivorydale plant—a life-size marble sculpture of William Cooper Procter, grandson of cofounder William Procter, striding forward from the inscribed words: “He lived a life of noble simplicity, believing in God and the inherent worthiness of his fellow men.”83

New hires—especially those in brand management (the central function of the company)—immediately find nearly all of their time occupied by working or socializing with other members of “the family,” from whom they further learn about the values and practices of P&G. The company’s relatively isolated location in a P&G-dominated city (Cincinnati) further reinforces the sense of complete immersion into the company. “You go to a strange town, work together all day, write memos all night, and see each other on weekends,” described one P&G alum.84 P&Gers are expected to socialize primarily with other P&Gers, belong to the same clubs, attend similar churches, and live in the same neighborhoods.85

P&G has a long historical track record of paternalistic and progressive employee pay and benefit programs, which bind its people closely to the company.86

• In 1887, P&G introduced a profit-sharing plan for workers, making it the oldest profit-sharing plan in continuous operation in American industry.

• In 1892, P&G introduced an employee stock ownership plan, one of the first in industrial history.

• In 1915, P&G introduced a comprehensive sickness-disability-retirement-life-insurance plan—again, one of the first companies to do so.

The company has used these programs not only as a means of rewarding employees, but also as mechanisms to influence behavior, gain commitment, and ensure tightness of fit. A P&G publication described how it used the early profit-sharing plan:

[William Cooper Procter] concluded that workers who showed indifference to the need for greater work effort should be deprived of their share of profits—that their shares should be turned over to those who cared. So he set up four classifications—based on the degree of a worker’s cooperation as decided by management. That helped considerably [to ensure the proper attitude]!87

By encouraging employees to purchase shares in the employee stock ownership program, the company garnered a high level of psychological commitment. After all, what better way to gain “buy in” to the organization than to have employees literally buy in with some of their own hard-earned income? In 1903, to further reinforce this buy-in process, P&G restricted its profit-sharing program only to those willing to make a significant stock purchase commitment:

Profit sharing would [henceforth] be tied directly to employee ownership of P&G common stock. To be eligible for profit sharing, an employee had to buy stock equivalent at current value to his annual wage [emphasis ours], but could spread payment over several years with a minimum payment of four percent of his annual wage. At the same time, the Company contributed 12 percent of the employee’s annual wage toward purchase of that stock.88

By 1915, fully 61 percent of employees had bought in to the stock program—and thereby bought full psychological membership in P&G. Throughout its history, P&G has used a myriad of tangible mechanisms to enforce desired behavior, ranging from strong dress codes and office layouts that allow little privacy to P&G’s famous “one-page memo”* that mandates consistency in communication style.

P&G’s tightness of fit applies across the company, at all locations, in all countries, and in all world cultures. An ex-employee who joined P&G directly out of business school to work in Europe and Asia commented: “Procter’s culture extends to all corners of the globe. When going overseas, it was made very clear to me that I must first and foremost adapt to the P&G culture, and secondarily adapt to the national culture. Belonging to P&G is like belonging to a nation unto itself.”89 At a company meeting in 1986, chief executive John Smale echoed a similar theme:

Procter & Gamble people all over the world share a common bond. In spite of cultural and individual differences, we speak the same language. When I meet with Procter & Gamble people—whether they are in Sales in Boston, Product Development at the Ivorydale Technical Center, or the Management Committee in Rome—I feel I am talking to the same kind of people. People I know. People I trust. Procter & Gamble people.90

Like Nordstrom, IBM, and Disney, Procter & Gamble has displayed an intense penchant for secrecy and control of information. Managers routinely admonish, scold, or penalize employees for working on airplanes, using luggage ID cards that reveal them as P&G employees, and for talking about business in public places. The 1991 management stock option plan stipulates that if the recipient of the options discloses unauthorized information about P&G to the outside world, the options will be revoked.91

The company’s secretive nature reinforces an elitism cultivated throughout much of its history. P&G people feel proud to be part of an organization that describes itself as “special,” “great,” “excellent,” “moral,” “self-disciplined,” full of “the best people,” “an institution,” and “unique among the world’s business organizations.”92 In describing a particularly difficult project, a P&G manager commented: “If there was one characteristic I saw demonstrated by everyone [throughout the project] it was the pride in being the best.”93

The contrast between P&G and Colgate is not as stark as between Nordstrom and Melville, IBM and Burroughs, or Disney and Columbia. For one thing, up until the early 1900s, Colgate placed great emphasis on a paternalistic culture built around the Colgate family values.94 Nonetheless, there is a difference, particularly over the past sixty years. We found no evidence that Colgate imposes the same rigorous screening or tightness-of-fit criteria upon new hires. Nor did we find any evidence of the same level of indoctrination into the “character” of P&G and the guiding principles laid down by its founders. Whereas P&G has always defined itself in terms of its own core ideology and deep heritage—constantly emphasizing its specialness and uniqueness—Colgate has increasingly defined itself in relation to P&G. Procter has continually reinforced a sense of being the elite of the elite; Colgate has come to see itself as “second to Procter” and on a quest to become “another P&G.”95

THE MESSAGE FOR CEOS, MANAGERS, AND ENTREPRENEURS

You might find yourself somewhat uncomfortable with the findings in this chapter. We share some of that discomfort, and we wish to be clear that we’re certainly not advocating (or even describing) the extreme Jim Jones, David Koresh, or Reverend Sun Myung Moon type of situation. It is important to understand that, unlike many religious sects or social movements which often revolve around a charismatic cult leader (a “cult of personality”), visionary companies tend to be cult-like around their ideologies. Notice, for example, how Nordstrom created a zealous and fanatical reverence for its core values, shaping a powerful mythology about the customer service heroics of its employees, rather than demanding slavish reverence for an individual leader. Disney’s zealous protection of its values transcended Walt and remained largely intact decades after his death. P&G remained tightly dedicated to its principles for over 150 years, through nine generations of top management. Cultism around an individual personality is time telling; creating an environment that reinforces dedication to an enduring core ideology is clock building.

THE point of this chapter is not that you should set out to create a cult of personality. That’s the last thing you should do.

Rather, the point is to build an organization that fervently preserves its core ideology in specific, concrete ways. The visionary companies translate their ideologies into tangible mechanisms aligned to send a consistent set of reinforcing signals. They indoctrinate people, impose tightness of fit, and create a sense of belonging to something special through such practical, concrete items as:

• Orientation and ongoing training programs that have ideological as well as practical content, teaching such things as values, norms, history, and tradition

• Internal “universities” and training centers

• On-the-job socialization by peers and immediate supervisors.

• Rigorous up-through-the-ranks policies—hiring young, promoting from within, and shaping the employee’s mind-set from a young age

• Exposure to a pervasive mythology of “heroic deeds” and corporate exemplars (for example, customer heroics letters, marble statues)

• Unique language and terminology (such as “cast members,” “Motorolans”) that reinforce a frame of reference and the sense of belonging to a special, elite group

• Corporate songs, cheers, affirmations, or pledges that reinforce psychological commitment

• Tight screening processes, either during hiring or within the first few years

• Incentive and advancement criteria explicitly linked to fit with the corporate ideology

• Awards, contests, and public recognition that reward those who display great effort consistent with the ideology. Tangible and visible penalties for those who break ideological boundaries

• Tolerance for honest mistakes that do not breach the company’s ideology (“non-sins”); severe penalties or termination for breaching the ideology (“sins”)

• “Buy-in” mechanisms (financial, time investment)

• Celebrations that reinforce successes, belonging, and specialness

• Plant and office layout that reinforces norms and ideals

• Constant verbal and written emphasis on corporate values, heritage, and the sense of being part of something special

Preserve the Core AND Stimulate Progress

At this point, you might thinking: But isn’t a tight, cult-like culture dangerous? Does it lead to group-think and stagnation? Does it drive away talented people? Does it stifle creativity and diversity? Does it inhibit change? Our answer: Yes, a cult-like culture can be dangerous and limiting if not complemented with the other side of the yin-yang. Cult-like cultures, which preserve the core, must be counterweighted with a huge dose of stimulating progress. In a visionary company, they go hand in hand, each side reinforcing the other.

A cult-like culture can actually enhance a company’s ability to pursue Big Hairy Audacious Goals, precisely because it creates that sense of being part of an elite organization that can accomplish just about anything. IBM’s cultish sense of itself contributed greatly to its ability to gamble on the IBM 360. Disney’s cult-like belief in its special role in the world enhanced its ability to launch such radical BHAGs as Disneyland and EPCOT center. Without Boeing’s dedication to being an organization of people who “live, breathe, eat and sleep what they are doing,” it could not have successfully launched the 707 and 747 projects. Without Sony’s almost fanatical belief that it was a unique organization with a special role to play in the world, it could not have taken its bold steps with transistors in the 1950s. Merck’s cult-like dedication to its ideology gave its people a sense that they were part of something more than just another corporation—and it is largely out of this sense that they were inspired to put forth the effort required to establish Merck as the preeminent pharmaceutical company in the world.

Furthermore, it’s important to understand that you can have a cult-like culture of innovation, or a cult-like culture of competition, or a cult-like culture of change. You can even have a cult-like culture of zaniness. We think that’s exactly what executives at Wal-Mart do through such actions as leading thousands of screaming associates in the Wal-Mart cheer: “Give Me a W! Give Me an A! Give Me an L! Give Me a Squiggly! (Employees twist and squiggle their hips.) Give me an M! Give Me an A! Give Me an R! Give Me a T! What’s that spell? Wal-Mart! What’s that spell? Wal-Mart! Who’s number one? THE CUSTOMER!”96

Cult-like tightness and diversity can also work hand in hand. Some of the most cult-like visionary companies have received accolades as being the best major corporations for women and minorities. Merck, for example, has a long track record of progressive equal opportunity programs. At Merck, diversity is a form of progress that nicely complements its deeply cherished core. You can be any color, size, shape, or gender at Merck—just as long as you believe in what the company stands for.

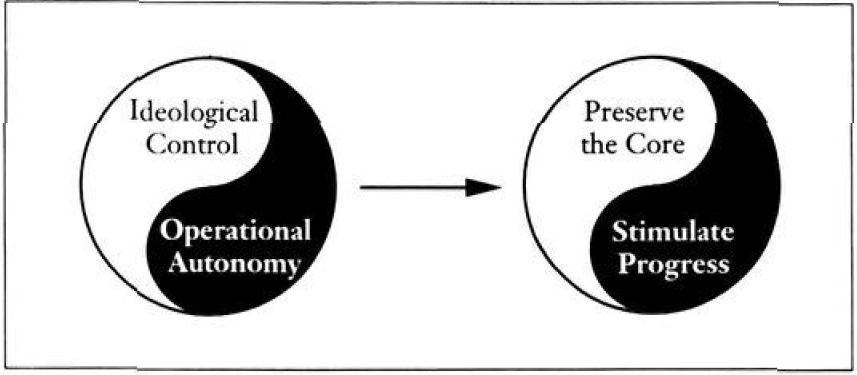

IDEOLOGICAL CONTROL/OPERATIONAL AUTONOMY

In a classic example of the “Genius of the AND” prevailing over the “Tyranny of the OR,” visionary companies impose tight ideological control and simultaneously provide wide operating autonomy that encourages individual initiative. In fact, as we will discuss in the next chapter, we found that the visionary companies were significantly more decentralized and granted greater operational autonomy than the comparison companies as a general pattern, even though they have been much more cult-like.97 Ideological control preserves the core while operational autonomy stimulates progress.

Recall the Nordstrom one-page employee handbook described at the beginning of this chapter. Notice how, on the one hand, the company constricts behavior to that consistent with the Nordstrom ideology. Yet, on the other hand, it grants immense operating discretion. When asked during a visit to a Stanford Business School class how a Nordstrom clerk would handle a customer attempting to return a dress that had obviously been worn, Jim Nordstrom replied:

I don’t know. That’s an honest answer. But I do have a high level of confidence that it would be handled in such a way that the customer would feel well treated and served. Whether that would involve taking the dress back would depend on the specific situation, and we want to give each clerk a lot of latitude in figuring out what to do. We view our people as sales professionals. They don’t need rules. They need basic guideposts, but not rules. You can do anything you need to at Nordstrom to get the job done, just so long as you live up to our basic values and standards.98

Nordstrom reminds us of the United States Marine Corps—tight, controlled, and disciplined, with little room for those who will not or cannot conform to the ideology. Yet, paradoxically, those without individual initiative and entrepreneurial instincts will just us likely fail at Nordstrom as those who do not share the ideological tenets. The same holds at other ideologically tight visionary companies like 3M, J&J, Merck, HP, and Wal-Mart.

This finding has massive practical implications. It means that companies seeking an “empowered” or decentralized work environment should first and foremost impose a tight ideology, screen and indoctrinate people into that ideology, eject the viruses, and give those who remain the tremendous sense of responsibility that comes with membership in an elite organization. It means getting the right actors on the stage, putting them in the right frame of mind, and then giving them the freedom to ad lib as they see fit. It means, in short, understanding that cult-like tightness around an ideology actually enables a company to turn people loose to experiment, change, adapt, and—above all—to act.

* “Robert”—a typical Nordstrom new hire—is a composite character, but the experience described is authentic. We created a description of Robert’s experience based on interviews with employees and ex-employees, transcript notes from an interview with co-chairman Jim Nordstrom, company documents, book excerpts, and articles.

* We found that the visionary companies put more emphasis on employee training in general. Not just ideological orientation, but also skills and professional development training. We will return to this point in a later chapter.

* NOTE: for an excellent account of IBM’s early history, see Robert Sobel, IBM: Colossus in Transition (New York: Truman Talley Books, 1981).

* All memos are supposed to be kept to one page, plus exhibits. Most P&Gers conform to this rule, although some P&Gers have in fact seen memos longer than one page.