Chapter 8

Home-Grown Management

From now on, [choosing my successor) is the most important decision I’ll make. It occupies a considerable amount of thought almost every day.

JACK WELCH, CEO, GENERAL ELECTRIC, SPEAKING ABOUT SUCCESSION PLANNING IN 1991—NINE YEARS BEFORE HIS ANTICIPATED RETIREMENT.1

One responsibility [we] considered paramount is seeing to the continuity of capable senior leadership. We have always striven to have proven backup candidates available, employed transition training programs to best prepare the prime candidates, and been very open about [succession planning].. . We believe that continuity is immensely valuable.

ROBERT W. GALVIN, FORMER TEAM MEMBER OF THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICE, MOTOROLA CORPORATION, 19912

In 1981, Jack Welch became chief executive of the General Electric Company. A decade later, he had become legendary in his own time, “widely acknowledged,” according to Fortune magazine, “as the leading master of corporate change in our time.”3 To read the myriad of articles on Welch’s revolution, we might be tempted to picture him as a savior riding in on a white horse to rescue a severely troubled company that had not changed significantly since the invention of electricity. If we did not know Welch’s background or GE’s history, we might be lured into thinking that he must have been brought in from the outside as “new blood” to shake up a lumbering, complacent behemoth.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

For one thing, Welch was pure GE home-grown stock, having joined the company directly out of graduate school one month before his twenty-fifth birthday. It was his first full-time job, and he worked at GE for twenty consecutive years before becoming chief executive.4 Like every single one of his predecessors, Welch came from deep inside the company.

Nor did Welch inherit a grossly mismanaged company. Quite the opposite. Welch’s immediate predecessor, Reginald Jones, retired as “the most admired business leader in America.”5 A survey of his peers in U.S. News and World Report found Jones to be “the most influential person in business today”—not once, but twice, in 1979 and 1980. Similar surveys in the Wall Street Journal and Fortune magazine also listed Jones at the top, and a Gallup poll named Jones CEO of the Year in 1980.6 In financial terms, such as profit growth, return on equity, return on sales, and return on assets, GE performed as well under Jones’s eight-year tenure as during Welch’s first eight years.7

Furthermore, Welch is not the first change agent or management innovator in GE’s panoply of chief executives. Under Gerard Swope (1922–1939), GE moved dramatically into home appliances. Swope also introduced the idea of “enlightened management”—new at the time to GE—with balanced responsibilities to employees, shareholders, and customers.8 Under Ralph Cordiner (1950–1963) and his slogan “Go for it,” GE exploded into a vast array of new arenas—a twentyfold increase in the number of market segments served.9 Cordiner radically restructured and decentralized the company, instituted management by objective (one of the first companies in America to do so), created Crotonville (GE’s now-famous management training and indoctrination center), and wrote the influential book New Frontiers for Professional Managers.10 Fred Borch’s tenure (1964–1972) was “a time of creative ferment” and a willingness to make bold, risky investments in such areas as jet aircraft engines and computers.11 Reginald Jones (1973–1980) became a leader in changing the relationship between business and government.

Indeed, Welch comes from a long heritage of managerial excellence atop GE. Using pretax return on equity (ROE) as a basic benchmark of financial performance, GE under Welch’s predecessors performed as well on average since 1915 as GE during Welch’s first decade in office—26.29 percent for Welch and 28.29 percent for his predecessors.12 In fact, when we ranked GE chief executive eras by return, the Welch era came in fifth place out of seven. (Every single GE chief executive, including Welch, outperformed rival Westinghouse in ROE during their tenure.) Of course, a straight ROE calculation doesn’t take into account the ups and downs of industry cycles, wars, depressions, and the like. So we also rank-ordered GE chief executive eras in terms of average annual cumulative stock returns relative to the market and Westinghouse.13 On this basis, we found Welch in second and fifth* place, respectively, relative to his predecessors. An excellent performance, but not the best in GE history. (See Table A.9 in Appendix 3.)

This is no way detracts from Welch’s immense achievements. He ranks as one of the most effective chief executive officers in American business history. But—and this is the crucial point—so do his predecessors. Welch changed GE. So did his predecessors. Welch outperformed his counterparts at Westinghouse. So did his predecessors. Welch became widely admired by his peers—a “management guru” of his age. So did his predecessors. Welch laid the groundwork for the future prosperity of GE. So did his predecessors. We respect Welch for his remarkable track record. But we respect GE even more for its remarkable track record of continuity in top management excellence over the course of a hundred years.

TO have a Welch-caliber CEO is impressive. To have a century of Welch-caliber CEOs all grown from inside—well, that is one key reason why GE is a visionary company.

In fact, the entire selection process that resulted in Welch becoming CEO was traditional GE at its best. Welch is as much a reflection of GE’s heritage as he is a change agent for GE’s future. As longtime GE consultant Noel Tichy and Fortune magazine editor Stratford Sherman described in Control Your Own Destiny or Someone Else Will:†

The management-succession process that placed venerable General Electric in Welch’s hands exemplifies the best and most vital aspects of the old GE culture. [Prior CEO Reginald] Jones spent years selecting him from a group of candidates so highly qualified that almost all of them ended up heading major corporations. . . . Jones insisted on a long, laborious, exactingly thorough process that would carefully consider every eligible candidate, then rely on reason alone to select the best qualified. The result ranks among the finest examples of succession planning in corporate history.14

Jones took the first step in that process by creating a document entitled “A Road Map for CEO Succession” in 1974—seven years before Welch became CEO. After working closely with GE’s Executive Manpower Staff, he spent two years paring an initial list of ninety-six possibilities—all of them GE insiders—down to twelve, and then six prime candidates, including Welch. To test and observe the candidates, Jones appointed each of the six to be “sector executives,” reporting directly to the Corporate Executive Office. Over the next three years, he gradually narrowed the field, putting the candidates through a variety of rigorous challenges, interviews, essay contests, and evaluations.15 A key part of the process included the “airplane interviews,” wherein Jones asked each candidate: “You and I are flying in a company plane. It crashes. You and I are both killed. Who should be chairman of General Electric?” (Jones learned this technique from his predecessor, Fred Borch.)16 Welch eventually won the grueling endurance contest over a strong field; runner-up candidates went on to become president or CEO of such companies as GTE, Rubbermaid, Apollo Computer, and RCA.17 As an interesting aside, more GE alumni have become chief executives at American corporations than alumni of any other company.18

Westinghouse, in contrast to GE, has been rocked by periods of turmoil and discontinuity at the top. Westinghouse has had nearly twice as many CEOs as GE, some with tenure of less than two years. The average Westinghouse CEO remained in office eight years, compared to fourteen years at GE. Furthermore, Westinghouse has periodically resorted to hiring CEOs from the outside, rather than building on internal talent, as GE has always done. George Westinghouse was kicked out of the company in 1908 and replaced by two outsiders (both bankers) during a reorganization.19 In 1946, another outsider (again a banker) became CEO.20 Then in 1993, Westinghouse went outside yet again for a CEO—bringing in an ex-PepsiCo executive to run the company after it posted billion-dollar losses in 1991 and 1992.21

We would like to comment more explicitly about the internal succession process at Westinghouse, but we found scant material on this topic in outside publications or from the company itself. But that, too, is an interesting point. GE has paid such prominent, conscious attention to leadership continuity that both the company and outside observers have commented greatly on it. Westinghouse has paid significantly less attention to management development and succession planning.

PROMOTE FROM WITHIN TO PRESERVE THE CORE

Throughout this book, we’ve downplayed the role of leadership in a visionary company. Yet it would be outright wrong to state that top management doesn’t matter at all. It would be naive to suggest that any random person could become CEO of a visionary company, and it would still continue to tick along in top form. Top management will have an impact on an organization—in most cases, a significant impact. The question is, will it have the right kind of impact? Will management preserve the core while making its impact?

Visionary companies develop, promote, and carefully select managerial talent grown from inside the company to a greater degree than the comparison companies. They do this as a key step in preserving their core. Over the period 1806 to 1992, we found evidence that only two visionary companies (11.1 percent) ever hired a chief executive directly from outside the company, compared to thirteen (72.2 percent) of the comparison companies. Of 113 chief executives for which we have data in the visionary companies, only 3.5 percent came directly from outside the company, versus 22.1 percent of 140 CEOs at the comparison companies. In other words, the visionary companies were six times more likely to promote insiders to chief executive than the comparison companies. (See Table 8.1 in the text and Table A.8 in Appendix 3.)

PUT another way, across seventeen hundred years of combined history in the visionary companies, we found only four individual cases of an outsider coming directly into the role of chief executive.

In short, it is not the quality of leadership that most separates the visionary companies from the comparison companies. It is the continuity of quality leadership that matters—continuity that preserves the core. Both the visionary companies and the comparison companies have had excellent top management at certain points in their histories. But the visionary companies have had better management development and succession planning—key parts of a ticking clock. They thereby ensured greater continuity in leadership talent grown from within than the comparison companies in fifteen out of eighteen cases. (See Table A.8 in Appendix 3.)

Table 8.1

Companies that Put Outsiders into Chief Executive Roles22 1806–1992

| Visionary Companies | Comparison Companies |

| Philip Morris | Ames |

| Walt Disney | Burroughs |

| Chase Manhattan | |

| Colgate | |

| Columbia | |

| General Motors | |

| Howard Johnson | |

| Kenwood | |

| Norton | |

| R.J. Reynolds | |

| Wells Fargo | |

| Westinghouse | |

| Zenith | |

NOTE: IBM hired an outsider as CEO (Louis Gerstner) in 1993, the year after we cut off the data for our analysis. We did not count William Allen at Boeing as an outsider because he had been actively involved in major management decisions (such as reorganizations, R&D investments, financing structures, and business strategy) for twenty years as the company’s lawyer and fourteen years as a highly active director prior to becoming chief executive—a post he then held for twenty-three years. We are indebted to Morten Hansen for his background analysis for this table.

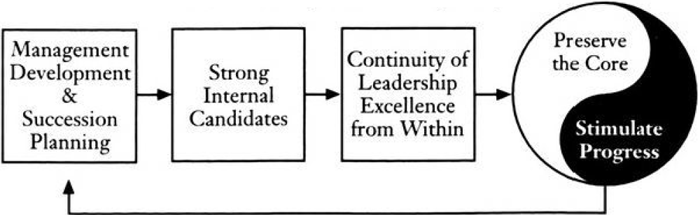

You can think of it as a continuous self-reinforcing process—a “leadership continuity loop”:

Leadership Continuity Loop

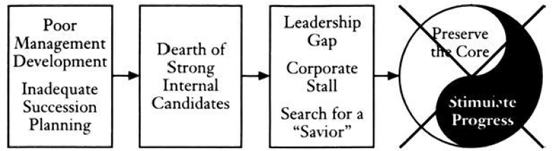

Absence of any of these elements can lead to management discontinuities that force a company to search outside for a chief executive—and therefore pull the company away from its core ideology. Such discontinuities can also impede progress, as a company stalls due to turmoil at the top. In fact, we saw a pattern common in the comparison companies that stands in contrast to the “management continuity loop” in the visionary companies. We came to call this pattern the “leadership gap and savior syndrome”:

Consider the following examples of Colgate versus P&G and Zenith versus Motorola.

Discontinuity at Colgate Versus Talent Stacked Like Cordwood at P&G

Up until the early 1900s, Colgate was an extraordinary company. Founded in 1806, the company had attained over a century of steady growth and was roughly the same size as P&G. It also had the strongest early statement of core ideology of any comparison company in our study, complete with core values and an enduring purpose articulated by Sidney Colgate.23 By the 1940s, however, Colgate had fallen to less than half the size and less than one-fourth the profitability of P&G, and remained at that ratio on average for the next four decades. It also drifted from its strong core ideology and became a company with a much weaker self-identity than Procter.

What happened? The answer lies partly in poor succession planning and resulting management discontinuities at Colgate relative to P&G. Colgate had been run entirely by insiders (all members of the Colgate family) for its first four generations of top management. However, the company failed in its management development and succession planning during the early 1900s. By the late 1920s, Colgate faced such a shortage of well-developed successors that it resorted to a merger with Palmolive-Peet which “put an alien management in office.”24 As a 1936 Fortune article described:

The brothers Colgate were getting old. Gilbert, the President, was seventy, Sidney was sixty-six. And Russell, who was only fifty-five, took no great part in the management. . . . Sidney’s son, Bayard Colgate, was. . . barely six years out of Yale. That, for a Colgate, was too young. So the brothers listened attentively when Charles Pearce offered to merge Palmolive-Peet with Colgate. . . . [After the merger], they resigned themselves to virtual retirement.

Pearce, who became chief executive of the combined company, proved to be a disaster. Driven by “a mania for expansion,”25 Pearce concentrated on an unsuccessful attempt to merge Colgate into a giant conglomerate with Standard Brands, Hershey, and Kraft. Distracted by his quest for sheer size, Pearce ignored the fundamentals of Colgate’s business and its basic values. He even moved headquarters from Jersey City, New Jersey (where it had resided close to the soap making operations for eighty-one years), to Chicago.26 During Pearce’s reign from 1928 to 1933, Colgate’s average return on sales declined by more than half (9.0 to 4.0 percent). During the same period P&G’s return on sales actually increased slightly (11.6 to 12.0 percent), despite the Depression.27

Pearce severely breached Colgate’s core ideology, especially its core value of fair dealing with retailers, customers, and employees.28 He drove such hard bargains with retailers that they revolted:

Druggists were especially irate: they had long been accustomed to the conservative dealings of the Colgates. The tactics of the Pearce . . . management pleased them not at all. And since Colgate . . . was depending on substantial profits from its toilet articles, . . . the defection of the druggists . . . was a ruinous blow.29

Finally, according to Fortune, the Colgate family “roused up from its lethargy to look astonished on what Charles Pearce had done.”30 Bayard Colgate (age thirty-six) replaced Pearce as chief executive, moved the headquarters back to New Jersey, and tried to reawaken the Colgate values and reestablish forward progress. However, Pearce’s reign of havoc made the CEO job particularly difficult for the young Colgate, who had not been prepared or groomed for such a role. He held the post for only five years, before passing the job to international sales manager Edward Little. Colgate fell behind P&G, never to catch up. During the decade immediately after the Pearce era, P&G grew twice as fast and attained four times the profits as Colgate.31

With the Pearce debacle, Colgate began a pattern of poorly handled top management succession. Edward Little (chief executive from 1938 to 1960) ran Colgate as a one-man show.32 “Colgate was dominated by [Little]—and ‘dominate’ is not too strong a term,” wrote Forbes.33 We found no evidence that Little could imagine Colgate without himself at the helm, or that the company had any succession plan in place. Finally, at age seventy-nine, Little retired, and Colgate had to call home one of its international vice presidents to ride in as a “White Knight” to turn around the company whose domestic operations were in serious trouble.34

In 1979, Colgate experienced yet another tumultuous transition at the top when chief executive David Foster was removed—against his will—by the Colgate board. Like his predecessors before him, Foster “carried on a tradition of one-man rule at Colgate, and it suited his temperament.”35 In fact, Foster actually impeded succession planning, according to an article in Fortune:

To the end, David Foster did his best to give his heir apparent the least possible power—or even visibility. . . . Foster [sought] an effective way to silence the board on the matter of succession. Colgate had an unwritten policy at the time calling for top executives to leave at sixty. Foster was then fifty-five and was saying he would adhere to the policy, but it is a telling comment that when [his potential heir] received an offer to become president of [another company], he took it.36

Rocked again by turmoil at the top, Colgate slid further behind P&G in both sales and profitability during the decade after Foster’s ouster, dropping to one-fourth the size of P&G in both sales and profits. Certainly factors other than chaotic management contributed to Colgate’s relative decline, including P&G’s superior R&D efforts and greater economies of scale. But—and this is the crucial point—Colgate first lost its chance to run even with P&G during the Pearce turmoil, and then continued with fits and stalls at critical transition points.

P&G, in contrast, suffered no lurches in management like those at Colgate, even though the two companies faced exactly the same challenge of moving beyond family governance at precisely the same point in history. During the 1920s, while the Colgate brothers neglected to develop worthy successors, Cooper Procter had been carefully preparing Richard Deupree—an insider who had joined P&G in 1909—to assume the role of chief executive.37 Under Cooper Procter’s watchful eye and coaching, Deupree assumed ever greater responsibility, eventually becoming chief operating officer in 1928 (the exact same year that Colgate “put an alien management in office”). In 1930, Deupree began a successful eighteen-year stint as chief executive—the first nonfamily CEO in P&G’s history. Then, like Procter before him, Deupree ensured continuity from generation to generation, as John Smale (CEO 1981–1989) described:

Deupree held a pivotal role in carrying out and handing down the character of the Company. He knew—and learned from—the only two people to precede him as Chief Executive Officer since Procter & Gamble was incorporated in 1890. And he also knew—and helped teach—the next four people to hold the job after him. I am one of these four people—only the seventh Chief Executive of this Company in the nearly 100 years since it’s been incorporated.38

P&G understood the importance of constantly developing managerial talent so as to never face gaps in succession at any level, and therefore to preserve its core throughout the company. Dun’s Review once commented that “P&G’s program for developing managers is so thoroughgoing and consistent that the company has talent stacked like cordwood—in every job and in every level.”39 All the way to senior management ranks, P&G aims at all times to “have two or three people equally capable of assuming responsibility of the next step up.”40 Deupree’s successor, Neil McElroy, explained: “Our [development] of people who. . . will be the management of the future goes on year after year, in good times and bad. If you don’t do it, X years from now we will have a gap. And we can’t stand a gap.”41

Leadership Gaps at Zenith Versus Motorola’s Deep Bench

“Commander” Eugene F. McDonald, Jr., the brilliant and domineering mastermind founder of Zenith Corporation, had developed no capable successors by the time he died in 1958. McDonald’s closest associate, Hugh Robertson, took over as chief executive, but he was already past the age of seventy. Fortune magazine commented in 1960, “Zenith is traveling largely on momentum imparted by . . . forceful personalities that belong to its past rather than its future.”42 Robertson held on for two years and passed the company to the highly conservative corporate counsel Joseph Wright, who allowed the company to drift away from its core value of fanatical dedication to high quality.43 Insider Sam Kaplan became chief executive in 1968, but died suddenly in 1970. Facing yet another management vacuum at the top, Zenith felt the need to find an outside savior to rescue the company. After an intensive search, Zenith hired John Nevin from Ford.44

After an unspectacular tenure and continued drift from the company’s original values, Nevin resigned in 1979, forcing ex-chairman Wright to come out of retirement at age sixty-eight “to try to put the company back on its feet.”45 Wright elevated Revone Kluckman to chief executive, but he—like Kaplan before him—died suddenly two years into his tenure, forcing yet another crisis transition.

In contrast, Motorola had none of the same turmoil—a model example of management continuity that preserves the core. Founder Paul Galvin began grooming his son Bob Galvin years before the formal transfer of power. The younger Galvin began work at Motorola in 1940 while still in high school, sixteen years before becoming president and nineteen years before becoming chief executive.46 Paul Galvin made sure that his son grew up from deep inside the business, having him begin as a stock clerk with a minimum of special privileges. When young Bob reported to the personnel office at seven A.M. to apply for a summer job, a manager offered to take him directly—out of turn—to see the head of personnel. Galvin declined. He wanted to go through the process from the bottom, just like every other Motorolan had to.47

Bob Galvin moved up through the business, finally sharing presidential duties for the three years preceding his father’s death. “In time, my father . . . announced we would act as one. Either of us could act on any issue. The other would support.”48 Paul Galvin’s biographer wrote that the transfer of experience from one generation to the next was a daily process that lasted years.49 Then, almost immediately after his father’s death in 1959, Bob Galvin began thinking about management development and succession planning for the next generation—a quarter of a century before he would pass the reins.

To reinforce the concept of leadership continuity from within, Bob Galvin discarded the traditional concept of a chief executive officer in favor of the concept of a Chief Executive Office occupied by “team members.” “Members” plural is not a misprint. Galvin envisioned an office held by multiple team members (usually three) at any one time, rather than a single leader. Galvin did this in part to ensure that the company would have capable insiders well positioned to assume leadership responsibility at any point in time. “There was always a private but clear understanding of succession hierarchy,” wrote Galvin. “We were prepared for unschedulable change throughout that quarter of a century [that I was a member of the Chief Executive Office.]”50

Motorola implemented this “Office Of” concept not only at the chief executive level, but also at lower levels (with two or three team members per office)—a key mechanism for management development and leadership continuity throughout the company. Aware that such an approach was controversial among management thinkers—not to mention awkward to manage—Galvin argued that the benefits far outweighed the costs, as he wrote in 1991:

If an Office Of at the top was to succeed, it needed candidates who had experienced and adapted to such a . . . role earlier in their career. It followed that the experience base had to be provided by similar assignments at business unit levels. . . . The Office Of has its disadvantages. Some incumbents just plain don’t prefer it. . . . Mixed signals can emanate from the office. . . . As a consequence, periodically some Office Ofs have not clicked. Some players departed or were benched. But it has worked well more often. . . . The proof is in the using. On balance it is a figure of merit. It has consistently provided the best informed succession answers. It absolutely helped to provide the proven source of Chief Executive Office candidates.51

In sixty-five years of history, Motorola has suffered no leadership discontinuities like those at Zenith. Motorola has continually reinvented itself (from battery repair for Sears radios to integrated circuits to satellite communications systems), yet displayed unbroken continuity in top management excellence steeped in its core values, even when it has unexpectedly lost top management talent. For example, in 1993, George Fisher—a key member of the Chief Executive Office—left Motorola to become chief executive at Kodak. At most companies, the unexpected departure of such a capable chief executive would cause disarray, turmoil, and a management gap—as happened at Zenith when CEOs died unexpectedly. But not at Motorola. The other two members of the chief executive office (Gary Tooker, age fifty-four, and Christopher Galvin, age forty-three) simply clicked into place to shoulder the extra responsibilities. Simultaneously, Motorola began an internal process to select a new third team member from its deep bench of well-trained managerial talent. In an article appropriately titled “Motorola Will Be Just Fine, Thanks,” the New York Times summed up: “Mr. Fisher had the luxury of making his move secure in the knowledge that Motorola could hardly be better positioned to absorb such a surprise.”52

Management Turmoil and Corporate Decline

Westinghouse, Colgate, and Zenith and are not the only examples of top management turmoil and discontinuity in our study. We found numerous such examples in the comparison companies.

It happened at Melville Corporation in the 1950s, when Ward Melville found he hadn’t adequately prepared any successors. Desperate to pass the company to somebody—anybody—because he was “anxious to retire,” Melville gave the job to a production manager who was ill prepared and didn’t even want the job. The company declined precipitously. “I was shocked to see how fast the numbers can deteriorate when the men are wrong,” Melville commented later.53 Melville then launched a year-long search for an outside CEO to come in and turn around the company. Fortunately, Melville had the wisdom to abandon the outside search and turn instead to developing a promising young insider who, over time, proved to be a very capable CEO.54

It happened at Douglas Aircraft in the late 1950s, as founder Donald Douglas turned his company over to an inadequately prepared Donald Douglas, Jr. “The younger Douglas could not possibly fill his old man’s shoes,” wrote one biographical account. “The son retaliated against those he considered his enemies [i.e., most of his father’s management], and . . . replaced experienced administrators with those who joined his team.”55 As Douglas, Jr., placed key friends in high positions, talented managers left the company when it needed them most to face the ever-growing onslaught from Boeing. During the early 1960s, the loss of managerial talent caught up with Douglas as it tried desperately—and unsuccessfully—to catch up to Boeing. Facing an epic crisis in 1966, Douglas, Jr., sought salvation in the form of a merger with McDonnell Aircraft.

It happened at R.J. Reynolds in the 1970s, as company director J. Paul Sticht—ex-president of Federated Department Stores—“helped torpedo the planned succession of an heir apparent, then maneuvered himself into the presidency,” according to Business Week.56 Sticht assumed chief executive responsibility and restocked the management team almost entirely with outsiders.57 Later, in one of the most famous senior management disasters in corporate history, Ross Johnson (a truly alien element to the company’s heritage) became CEO after RJR acquired Nabisco Brands in 1985. Well-documented in Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco by Bryan Burroughs and John Helyar, the Johnson era ended with a junk-bond-financed takeover by financiers Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co., who brought in yet another outside CEO.

It happened at Ames, as the founding family watched its creation destroyed by outsiders who were brought in due to lack of capable successors. It happened at Burroughs with its importation of outsider W. Michael Blumenthal from Bendix, when the company faced “an obvious gap in our management structure,” brought on because “new managers were not groomed during the years of [Ray W.] Macdonald’s dictatorial rule.”58 It also happened at Chase Manhattan, Howard Johnson, and Columbia Pictures.

It also happened at two recent high-profile cases in our visionary companies: Disney and IBM.

At Disney, Walt developed no capable successor, and the company floundered during the 1970s as managers ran around asking themselves, “What would Walt do?” To save the company, the board hired outsiders Michael Eisner and Frank Wells in 1984. We’d like to point out, however, that Disney consciously did its best to preserve ideological continuity even while selecting an outsider. Ray Watson, who guided the CEO search, wanted Eisner for the job not only because he had a stellar track record in the industry, but also because Eisner understood and appreciated—indeed, had unabashed enthusiasm for—the Disney values.59 As one Disneyite summed up: “Eisner turned out to be more Walt than Walt.”60

The Disney case illustrates an important point. If you’re involved with an organization that feels it must go outside for a top manager, then look for candidates who are highly compatible with the core ideology. They can be different in managerial style, but they should share the core values at a gut level.

What should one make of IBM’s 1993 decision to replace its internally grown CEO with Louis V. Gerstner—an outsider from R.J. Reynolds with no industry experience? How does this massive anomaly fit with what we’ve seen in our other visionary companies? It doesn’t fit. IBM’s decision simply doesn’t make any sense to us—at least not in the context of the seventeen hundred cumulative years of history we examined in the visionary companies.

Perhaps IBM’s board was operating under the assumption that dramatic change requires an outsider. To that assumption we respond simply: Jack Welch. The “leading master of corporate change in our time” spent his entire career inside the company that made him CEO. IBM has had one of the most thorough management development programs of any corporation on the planet. It has a long track record of hiring extraordinarily talented people. We simply cannot believe that IBM didn’t have at least one Welch-caliber change agent inside the company. Indeed, we would be surprised if there weren’t at least a dozen insiders equally capable as anyone IBM could attract from the outside.

AS companies like GE, Motorola, P&G, Boeing, Nordstrom, 3M, and HP have shown time and again, a visionary company absolutely does not need to hire top management from the outside in order to get change and fresh ideas.

IBM’s board and search committee wanted dramatic change and progress. With Mr. Gerstner, they’ll probably get it. But the real question for IBM—indeed, the pivotal issue over the next decade—is: Can Gerstner preserve the core ideals of IBM while simultaneously bringing about this momentous change? Can Gerstner be to IBM what Eisner has been to Disney? If so, then IBM might regain its revered place among the world’s most visionary companies.

THE MESSAGE FOR CEOS, MANAGERS, AND ENTREPRENEURS

Simply put, our research leads us to conclude that it is extraordinarily difficult to become and remain a highly visionary company by hiring top management from outside the organization. Equally important, there is absolutely no inconsistency between promoting from within and stimulating significant change.

If you’re the chief executive or board member at a large company, you can directly apply the lessons of this chapter. Your company should have management development processes and long-range succession planning in place to ensure a smooth transition from one generation to the next. We urge you to keep in mind how the Walt Disney Company—an American icon—got itself in a terrible fix because Walt neglected to build this vital part of a ticking clock. We urge you to not repeat the mistakes made at Colgate, Zenith, Melville, Ames, R.J. Reynolds, and Burroughs. Do not fall into the trap of thinking that the only way to bring about change and progress at the top is to bring in outsiders, who might dilute or destroy the core. The key is to develop and promote insiders who are highly capable of stimulating healthy change and progress, while preserving the core.

If you’re a manager, the essence of this chapter also applies to you. If you’re building a visionary department, division, or group within a larger company, you can also be thinking about management development and succession planning, albeit on a smaller scale. If you were hit by a bus, who could step into your role? What are you doing to help those people develop? What planning have you done to ensure a smooth and orderly transition when you move up to higher responsibilities? (You can also be asking those at higher levels what steps they have taken to ensure a smooth succession.) Finally, if you find a visionary company that you fit really well with, it might be worth your while to develop your skills within that company rather than job hop.

How does this chapter apply to smaller companies and entrepreneurs? Clearly, a small company cannot have a chief executive succession process that begins with ninety-six candidates, as happened at GE. Nonetheless, small to midsize companies can be developing managers and planning for succession. Motorola was still a small company when Paul Galvin began carefully grooming his son to become chief executive. The same holds true for family transitions during the early days of Merck, P&G, J&J, Nordstrom, and Marriott. Sam Walton began thinking about future management of the company before the company had even fifty stores.61 Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard began formal management development programs and thoughtful succession planning in the 1950s, when the company had five hundred employees.62

Interestingly, nearly all of the key early architects in the visionary companies remained in office for long periods of time (32.4 years on average), so few of the companies faced actual succession while still young and small. Nonetheless, many of them were planning for succession long before the actual moment of succession. If you’re a small-business person, this indicates taking a very long-term view. The entrepreneurial model of building a company around a great idea, growing quickly, cashing out, and passing the company off to outside professional managers will probably not produce the next Hewlett-Packard, Motorola, General Electric, or Merck.

From the perspective of building a visionary company, the issue is not only how well the company will do during the current generation. The crucial question is, how well will the company perform in the next generation, and the next generation after that, and the next generation after that? All individual leaders eventually die. But a visionary company can tick along for centuries, pursuing its purpose and expressing its core values long beyond the tenure of any individual leader.

* Given GE’s recent superb performance in the early 1990s and Westinghouse’s decline, we expect that the Welch era ranking will improve significantly on this dimension.

† Two books cover the Welch selection process in detail. One is Tichy and Sherman’s. The other is The New GE, by Robert Slater. In this section, we have drawn background data from both of these fine books.