On March 14, 1994, we shipped the final manuscript for Built to Last to our publisher. Like all authors, we had hopes and dreams for the book, but never dared allow these hopes to become predictions. We knew that for every successful book, ten or twenty equally good (or better) works languish in obscurity. Two years later, as we write this introduction to the paperback edition, we find ourselves somewhat astonished by the success of the book: more than forty printings worldwide, translation into thirteen languages, and best-seller status in North America, Japan, South America, and parts of Europe.

There are many ways to measure the success of a book, but for us the quality of our readership stands at the top of the list. Fueled initially by favorable coverage in a wide range of magazines and journals, the book quickly found an audience and ignited a word-of-mouth chain reaction among thoughtful readers. And that is a key word: readers. What is the true price of a book? Not the fifteen- to twenty-five-dollar cover price. For a busy person, the cover price pales in comparison to the hours required to read and digest a book, especially a research-based, idea-driven work like ours. Most people don’t read the books they buy, or at least not all of them. We’ve been pleasantly surprised not only by how many people have bought the book, but by how many have actually read it. From CEOs and senior executives to aspiring entrepreneurs, leaders of nonprofits, investors, journalists, and managers early in their careers, busy people have invested in Built to Last with their most precious resource—time.

We attribute this widespread readership to four primary factors. First, people feel inspired by the very notion of building an enduring, great company. We’ve met executives from all over the world who aspire to create something bigger and more lasting than themselves—an ongoing institution rooted in a set of timeless core values, that exists for a purpose beyond just making money, and that stands the test of time by virtue of the ability to continually renew itself from within.

We’ve seen this motivation not only in those who shoulder the responsibility of stewardship in large organizations, but also—and perhaps especially—in entrepreneurs and leaders of small to midsized companies. The examples set by people like David Packard, George Merck, Walt Disney, Masaru Ibuka, Paul Galvin, and William McKnight—the Thomas Jeffersons and James Madisons of the business world—set a high standard of values and performance that many feel compelled to try to live up to. Packard and his peers did not begin as corporate giants; they began as entrepreneurs and small business people. From there they built small, cash-strapped enterprises into some of the world’s most enduring and successful corporations. One executive of a small entrepreneurial company said, “To know that they did it gave us confidence and a model to follow.”

Second, thoughtful people crave time-tested fundamentals; they’re tired of the “fad of the year” boom-and-bust cycle of management thinking. Yes, the world changes—and continues to change at an accelerated pace—but that does not mean that we should abandon the quest for fundamental concepts that stand the test of time. On the contrary, we need them more than ever! Certainly, we always need to search for new ideas and solutions—invention and discovery move humankind forward—but the biggest problems facing organizations today stem not from a dearth of new management ideas (we’re inundated with them), but primarily from a lack of understanding the basic fundamentals and, most problematic, a failure to consistently apply those fundamentals. Most executives would contribute far more to their organizations by going back to basics rather than flitting off on yet another short-lived love affair with the next attractive, well-packaged management fad.

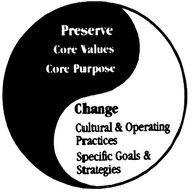

Third, executives at companies in transition find the concepts in Built to Last to be helpful in bringing about productive change without destroying the bedrock foundation of a great company (or, in some cases, building that bedrock for the first time). Contrary to popular wisdom, the proper first response to a changing world is not to ask, “How should we change?” but rather to ask, “What do we stand for and why do we exist?” This should never change. And then feel free to change everything else. Put another way, visionary companies distinguish their timeless core values and enduring purpose (which should never change) from their operating practices and business strategies (which should be changing constantly in response to a changing world). This distinction has proven to be profoundly useful to organizations amid dramatic transformation—defense companies like Rockwell facing the end of the Cold War, utilities like the Southern Company facing accelerating deregulation, tobacco companies like UST facing an increasingly hostile world, family companies like Cargill facing the first generation of nonfamily leadership, and companies with visionary founders like Advanced Micro Devices and Microsoft facing the need to transcend dependence on the founder.

Figure I.A

Continuity and Change in Visionary Companies

Even the visionary companies studied in Built to Last need to continually remind themselves of the crucial distinction between core and noncore, between what should never change and what should be open for change, between what is truly sacred and what is not. Hewlett-Packard executives, for example, speak frequently about this crucial distinction, helping HP people see that “change” in operating practices, cultural norms, and business strategies does not mean losing the spirit of the HP Way. Comparing the company to a gyroscope, HP’s 1995 annual report emphasizes this key idea: “Gyroscopes have been used for almost a century to guide ships, airplanes, and satellites. A gyroscope does this by combining the stability of an inner wheel with the free movement of a pivoting frame. In an analogous way, HP’s enduring character guides the company as we both lead and adapt to the evolution of technology and markets.” Johnson & Johnson used the concept to challenge its entire organization structure and revamp its processes while preserving the core ideals embodied in the Credo. 3M sold off entire chunks of its company that offered little opportunity for innovation—a dramatic move that surprised the business press—in order to refocus on its enduring purpose of solving unsolved problems innovatively. Indeed, if there is any one “secret” to an enduring great company, it is the ability to manage continuity and change—a discipline that must be consciously practiced, even by the most visionary of companies.

Fourth, there are many visionary companies out there, and they’ve found the book to be a welcome confirmation of their approach to business. The companies in our study represent only a small slice of the visionary company landscape. Visionary companies come in many packages: large and small, public and private, high profile and reclusive, stand-alone companies and subsidiaries. Well-known companies not in our original study such as Coca-Cola, L.L. Bean, Levi Strauss, McDonald’s, McKinsey, and State Farm almost certainly qualify as visionary companies, and others like Nike—not yet old enough—will probably enter that league. But there are also a large number of less well-known visionary companies, many of them private and somewhat reclusive. Some are older, well-established companies, such as Cargill, Edward D. Jones, Fannie Mae, Granite Rock, Molex, and Telecare. Others are up-and-coming companies, such as Bonneville International, Cypress, GSD&M, Landmark Communications, Manco, MBNA, Taylor Corporation, Sunrise Medical, and WL Gore. The business press tends to rivet our attention on the Icarus companies—high-profile firms either on the way up or the way down. We regularly come in contact with a very different group of companies—solid, paying attention to the fundamentals, shunning the limelight, creating jobs, generating wealth, and making a contribution to society. We feel optimistic as we see these companies—and there are a lot of them—make their way in the world.

BUILT TO LAST IN A GLOBAL, MULTICULTURAL WORLD

Given that seventeen of the eighteen visionary companies we studied for Built to Last have their headquarters in the United States, we were unsure how the basic concepts would play in the rest of the world. Since publication we’ve learned that the central concepts in Built to Last apply worldwide, across cultures and in multicultural environments. Between the two of us, we’ve traveled to every continent except Antarctica delivering seminars and lectures and working with companies. We’ve worked in a wide variety of countries with distinct cultures, including Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Holland, Israel, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, South Africa, Switzerland, Thailand, and Venezuela. And, although we have not yet traveled extensively in all parts of Asia, the book has had a strong reception there, with translations in Chinese, Korean, and Japanese.

The aspiration to build an enduring great company is not uniquely American; we’ve met clock-builders in every culture. Enlightened business leaders around the globe intuitively understand the importance of timeless core values and a purpose beyond just making money. They also exhibit the same relentless drive for progress we found in those who built the American visionary companies. We’ve seen BHAGs in Brazil, cult-like cultures in Scandinavia, “try a lot of stuff and keep what works” strategies in Israel, continuous self-improvement in South Africa. And the best organizations everywhere pay close attention to consistency and alignment.

The fact that we primarily studied U.S.-based firms for Built to Last reflects our research methodology more than the global corporate landscape (we assembled our list of visionary companies by surveying 700 CEOs of companies based in the United States). Established and up-and-coming visionary companies exist in many countries—FEMSA in Mexico, Husky in Canada, Odebrecht in Brazil, Sun International in England, Honda in Japan, to name a few. In a new research initiative designed to replicate the Built to Last analysis and systematically test the ideas in Europe, Jerry (in conjunction with OCC, a European consulting firm) has identified eighteen European visionary companies: ABB, BMW, Carrefour, Daimler Benz, Deutsche Bank, Ericsson, Fiat, Glaxo, ING, L’Oréal, Marks & Spencer, Nestlé, Nokia, Philips, Roche, Shell, Siemens, and Unilever.

We’ve also seen how the concepts apply to multinational or global companies that have many cultures within one organization. A global visionary company separates operating practices and business strategies (which should vary from country to country) from core values and purpose (which should be universal and enduring within the company, no matter where it does business). A visionary company exports its core values and purpose to all of its operations in every country, but tailors its practices and strategies to local cultural norms and market conditions. For example, Wal-Mart should export its core value that the customer is number one to all of its operations overseas, but should not necessarily export the Wal-Mart cheer (which is merely a cultural practice to reinforce the core value).

In our advisory work we’ve been able to help multinational companies discover and articulate a unifying, global core ideology. In one company with operations in twenty-eight countries, most of the executives—a cynical and skeptical group—simply didn’t believe it possible to find a shared set of core values and a common purpose that would be both global and meaningful. Through an intense process of introspection, beginning with each executive thinking about the core values he or she personally brings to his or her work, the group did indeed discover and articulate a shared core ideology. They also decided upon specific implementation steps to create alignment and bring the core to life on a consistent basis in all twenty-eight countries. The executives did not set new core values and purpose; they discovered a core that they already had in common but that had been obscured by misalignments and lack of dialogue. “For the first time in my fifteen years here,” said one executive, “I feel like we have a common identity. It feels good to know that my colleagues halfway around the globe hold the same fundamental ideals and principles, even though they may have very different operations and strategies. Diversity is a strength, especially when rooted in a common understanding of what we stand for and why we exist. Now we must make sure this permeates the entire institution and lasts over time.”

When operating at their best (which they don’t always do), enduring, great companies do not abandon their core values and high performance standards when doing business in different cultures. As the CEO of a more than one-hundred-year-old, privately-held, multibillion dollar visionary company explained: “It may take us longer to get established in a new culture, especially as we have difficulty finding people who fit with our value system. Take China and Russia, for example, where you’ll find rampant corruption and dishonesty. So, we move more slowly, and grow only as fast as we can find people who will uphold out standards. And we’re willing to forgo business opportunities that would force us to abandon our principles. We’re still here after one hundred years, doubling in size every six or seven years, when most of our competitors from fifty years ago don’t even exist anymore. Why? Because of the discipline to not compromise our standards for the sake of expediency. In everything we do, we take the long view. Always.”

BUILT TO LAST OUTSIDE OF CORPORATIONS

Given that we limited our original research to for-profit corporations, we did not know at the time how our findings would appeal to people outside of the corporate world. We’ve come to understand since publication that, ultimately, this is not a business book, but a book about building enduring, great human institutions of any type. People in a wide range of noncorporate situations report that they’ve found the concepts valuable—from for-cause organizations like the American Cancer Society to school districts, colleges, universities, churches, teams, governments, and even families and individuals.

Numerous healthcare organizations, for example, have found the concept of distinguishing their core values from their practices and strategies to be critical to maintaining their sense of social mission while adapting to the dramatic changes and increasing competitiveness of the world around them. A member of the board of trustees at a major university used the same idea to distinguish the timeless core value of intellectual freedom from the operating practice of academic tenure. “This distinction proved invaluable in helping me to facilitate needed changes in an increasingly archaic tenure system, while not losing sight of a very important core ideal,” he explained.

The concept of “clock building” an organization with a strong cult-like culture that transcends dependence on the original visionary founders has aided a number of social-cause organizations. One such entity is City Year, a community-service program that inspires hundreds of college-age youths to dedicate themselves to a year of communal effort on projects that improve America’s inner cities—a “domestic Peace Corps.” Like many social-cause organizations, City Year’s roots trace to inspired and visionary founders with a strong sense of social purpose. Alan Khazei, one of the founders, wanted his missionary zeal and vision to become a characteristic of the organization itself, independent of any individual leader, including himself. He made the shift from being a social visionary to building an organization with an enduring social purpose—the shift from being a time-teller to being a clock-builder. Social-cause organizations often begin in response to a specific problem, much as companies often begin in response to a specific great idea or timely market opportunity. But, just as any great idea or market opportunity eventually becomes obsolete, the founding goal of a social-cause organization can be met or become irrelevant. Looking for a deeper, more enduring purpose that goes beyond the original founding concept therefore becomes vitally important to building a lasting organization.

Conceptually, we see little difference between for-profit visionary companies and nonprofit visionary organizations. Both face the need to transcend dependence on any single leader or great idea. Both depend on a timeless set of core values and an enduring purpose beyond just making money. Both need to change in response to a changing world, while simultaneously preserving their core values and purpose. Both benefit from cult-like cultures and careful attention to succession planning. Both need mechanisms of forward progress, be they BHAGs (Big Hairy Audacious Goals), experimentation and entrepreneurship, or continuous self-improvement. Both need to create consistent alignment to preserve their core values and purpose and to stimulate progress. Certainly, the structures, strategies, competitive dynamics, and economics vary from for-profit to nonprofit institutions. But the essence of what it takes to build an enduring, great institution does not vary.

We’ve also begun to see how the concepts in Built to Last can be applied at the societal/governmental level. Japan and Israel, for example, have consciously tried to cultivate cohesive societies around a strong sense of purpose and core values, mechanisms of alignment, and national BHAGs. As historian Barbara Tuchman observed in her book Practicing History, “With all its problems, Israel has one commanding advantage: a sense of purpose. Israelis may not have affluence ... or the quiet life. But they have what affluence tends to smother: a motive.” This motive does not depend on the presence of a single charismatic visionary leader; it lies deep in the fabric of Israeli society, reinforced by powerful alignment mechanisms like universal military service. As a leading Israeli journalist described, “Unlike most nations, we actually have an enduring purpose that every Israeli knows: to provide a secure place on Earth for the Jewish people.”

In the United States, we have a strong set of national core values, beautifully articulated in the Declaration of Independence and the Gettysburg Address, but we need to gain better understanding of our enduring core purpose. Whereas the vast majority of Israeli citizens could tell you why Israel exists, we doubt we would find the same cohesiveness in modern-day America. The majority of American citizens also seem confused about how our timeless core values differ from practices, structures, and strategies. Is no gun control a core value or a practice? Is affirmative action a core value or a strategy? At a national level, we would benefit from rigorously applying the concept of “preserve the core/stimulate progress” to separate core values from practices and strategies so as to bring about productive change while preserving our national ideals.

Finally, and perhaps most intriguing, a significant number of people have reported to us that they’ve found the key concepts useful in their personal and family lives. Many have applied the yin and yang concept of “preserve the core/stimulate progress” to the fundamental human issues of self-identity and self-renewal. “Who am I? What do I stand for? What is my purpose? How do I maintain my sense of Self in this chaotic, unpredictable world? How do I infuse meaning into my life and work? How do I remain renewed, engaged, and stimulated?” These questions challenge us at least as much, or perhaps more so, today as ever before. With the demise of the myth of job security, the accelerating pace of change, and the increasing ambiguity and complexity of our world, people who depend on external structures to provide continuity and stability run the very real risk of having their moorings ripped away. The only truly reliable source of stability is a strong inner core and the willingness to change and adapt everything except that core. People cannot reliably predict where they are going and how their lives will unfold, especially in today’s unpredictable world. Those who built the visionary companies wisely understood that it is better to understand who you are than where you are going—for where you are going will almost certainly change. It is a lesson as relevant to our individual lives as to aspiring visionary companies.

ONGOING LEARNING AND FUTURE WORK

We’ve learned much since publication, and we have much more to learn. We’ve learned that time-tellers can become clock-builders, and we’re learning how to help time-tellers make the transition. We’ve learned that, if anything, we underestimated the importance of alignment, and we’re learning much about how to create alignment within organizations. We’ve learned that purpose—when properly conceived—has a profound effect upon an organization beyond what core values alone can do, and that organizations should put more effort into identifying their purpose. We’ve learned that mergers and acquisitions pose special problems for visionary companies, and we’re learning how to help organizations think about mergers and acquisitions within the Built to Last framework. We’ve learned much about how to apply the ideas across cultures and in noncorporate settings. We’ve learned that the enduring great companies of the twenty-first century will need to have radically different structures, strategies, practices, and mechanisms than in the twentieth century; yet the fundamental concepts we present in Built to Last will become, if anything, even more important as a framework within which to design the organization of the future.

We have an inner drive to learn and teach, and that drive does not end with this book; it is only a beginning. We continue our quest to gain new insights, develop new concepts and ideas, and create application tools that make a contribution. Jim has set up a learning laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, for ongoing research and work with organizations. Jerry continues to teach and research at the Stanford University Graduate School of Business, where he has created a new course on visionary companies. As part of our ongoing quest, we would enjoy hearing from our readers about their experiences and observations in working with the Built to Last material, or to raise questions, challenges, and issues that we should consider in our future work. We hope to hear from you.

Jim Collins

Boulder, CO

Jerry Porras

Stanford, CA