Theory of Economic Interdependence and War

THE INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER laid out the basic dimensions of the trade expectations approach and how it could be applied to the history of the modern great power system since 1790. This chapter constitutes a more in-depth look at both the existing literature on interdependence and war and the theory of trade expectations itself. My overall goal is a simple one: I hope to show the advantages of viewing the world through the lens of the trade expectations logic in order to demonstrate that it clears up most of the logical problems that have bedeviled current scholarship. In subsequent chapters, we can then see whether the new approach is actually confirmed by both large-N quantitative analysis and detailed historical case studies.

My main concern with the extant literature is not that it is wrong but rather that it is underspecified. By not examining the role of expectations of future trade and investment on the calculation of decision makers, the literature is trapped in deductive models that are static and backward looking. Existing scholarship almost invariably assumes that it is some factor existing in a snapshot of time—either in the present moment or in the recent past—that is driving leaders to do what they do. Leaders enjoy the past and current gains from trade, and are peaceful (traditional liberalism); they see their present vulnerability and they worry (economic realism); they underestimate the other’s present resolve and they push too hard (signaling arguments); they have long-standing unit-level grievances and pathologies that get unleashed when trade levels fall (traditional liberalism again). Such are the basic causal orientations of the current theories on interdependence and war. My approach is fundamentally different. In a very real way, it does not matter in the least whether past and current levels of trade and investment have been low, as long as leaders have strongly positive expectations for the future. It is their future orientation and expectations of a future stream of benefits that will likely make the leaders incline to peace. Likewise, it does not matter whether past and current levels of commerce have been high if leaders believe they are going to be cut off tomorrow or in the near future. It is their pessimism about the future that will probably drive these leaders to consider hard-line measures and even war to safeguard the long-term security of the state.

What this chapter is asking for, in short, is a basic reorientation of the thinking about interdependence and war away from theories of comparative statics and toward dynamic theories that incorporate the future within their core deductive logics.1 It is only by capturing how leaders really think, something that necessarily involves estimates and assessments of future possibilities and probabilities, that we can build causal theories that actually work in the real world. As we will see, existing scholarship either completely ignores the impact of future variables in constructing their deductive theories or it makes implicit, fixed assumptions about how the future will unfold. Liberal arguments about trade, for example, almost invariably assume that the economic cooperation that is going on today will continue to flourish into the future as long as both sides have an incentive to punish defections, simply because rational actors will see that the absolute benefits of working together (the “mutual cooperation” or CC box of basic game theory) are greater than the benefits of trade conflict (the “mutual defection” or DD box). Realist arguments, on the other hand, assume that dependent great powers know that others will eventually cut them from access to vital goods and markets, given the incentives in anarchic systems to play the game of great power politics hard.

These assumptions are simply indefensible stipulations about the future that have no place in a properly specified dynamic theory. Such a dynamic theory would recognize both the deductive and empirical point that leaders’ level of optimism or pessimism regarding the future will vary greatly over time, depending on a whole host of more ultimate causal factors. It is then the task of good theory to specify what kind of factors are likely to play important roles in shaping estimates of the future, and how these factors are logically likely to act—either alone or in concert—to drive leaders’ beliefs about the future security of their states. If this is done properly, we should be able to understand how great powers in the real world will react when the boundary conditions and parameters of their existential situations change without notice or without their full control. And if, when we open up the documents, we see great powers actually planning and reacting within historical cases as the theory anticipates that they will do, then we know we are on to something.

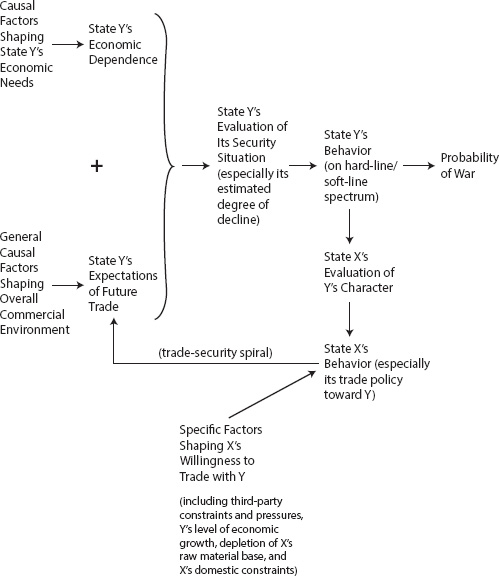

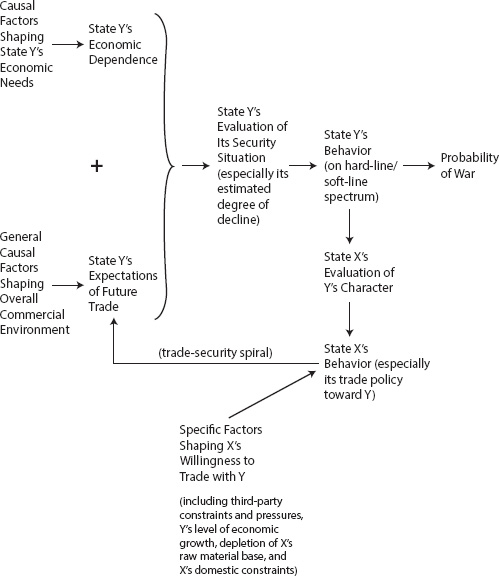

The task for the rest of this chapter is thus to provide this theoretical foundation for subsequent empirical analysis. I begin with a brief overview and critique of the current state of the literature. I also discuss the tricky question of why great powers would ever trade in the first place if they are driven primarily by security fears. This will set the stage for a more detailed explication of trade expectations theory. This process will take up most of the rest of the chapter. At the end of the chapter, I offer a quick review of how to test competing theories and a summary of my overall approach, drawing from an explanatory diagram that the reader may want to refer to as the chapter proceeds (figure 1.1). A discussion of my research method along with the value of quantitative approaches for the study of interdependence and conflict will be reserved until chapter 2.

OVERVIEW OF EXISTING THEORIES

The theories of international relations that explore the relationship between economic interdependence and war can be grouped according to three broad categories: liberalism, realism, and neo-Marxism. Many scholars might immediately contend that we should be moving beyond broad paradigmatic isms to focus on specific causal arguments, and I agree.2 In what follows, therefore, I will examine the specific causal claims that theorists make about how interdependence shapes the likelihood of war in world politics. Yet the broad labels of liberalism, realism, and neo-Marxism can still prove useful in grouping together theories that share a broad set of assumptions and assertions about what actors want from their policies (their ends), which individuals or domestic groups are most influential in driving policy (who matters), and the overall functional roles that trade and investment ties play in the onset of peace or war.

Liberal theories as a whole start with the assumption that actors, regardless of the level of analysis, are interested primarily in achieving material benefits for themselves. In short, actors seek to maximize utility defined in terms of the net material gains from peaceful commerce or war. The foundational model of liberalism, in this regard, is the “opportunity cost” model of trade and war. It begins with the premise that the state is a unitary, rational actor seeking to maximize the overall welfare of the nation as a whole. Trade provides valuable benefits, or gains from trade, to any particular state, as economic theory since the time of Adam Smith and David Ricardo has recognized. Any state that is dependent on trade should therefore seek to avoid war, since peaceful trading gives it all the benefits of close ties without any of the costs and risks associated with military conflict. In other words, the opportunity costs of waging war are high when trade levels are high, and this serves to restrain actors who might otherwise have an incentive for war.3 This straightforward logic supplied the foundation for the first wave of statistical correlational analyses in the field—studies that generally found that the higher a state’s trade level was relative to its GNP, the more peaceful its relations were with other states.4

Subsequent liberal theorists have expressed their dissatisfaction with the presumption that the state is a unitary actor, arguing that one cannot understand the causal processes underpinning the large-N finding that trade usually leads to peace without disaggregating the nation-state itself. Hence, over the last decade a number of scholars have opened up the black box of the state to explore exactly how a liberal commercial peace could arise, and what that might mean regarding the conditions for peace overall. Beth Simmons (2003), for instance, suggests that we examine how interdependence creates groups within polities that have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. Jonathan Kirshner (2007) asserts that open international financial flows makes bankers into a particular influential vested interest group, with bankers almost invariably wanting peace instead of war.5

Patrick McDonald (2007, 2009) has provided the most developed argument for the importance of domestic vested interests. He seeks to show that it is only a specific type of trading state that tends to have lower rates of militarized conflict—namely, the liberal capitalist one. McDonald maintains that capitalist states that operate through liberal economic institutions such as private property and competitive market structures are generally less aggressive. Exporters that have a vested interest in keeping peaceful trade going will operate as a powerful domestic group, exerting a strong check on any illiberal policy elites that happen to be running the state. Conversely, in more mercantilist states that do not respect private property or open trade, illiberal leaders with possibly aggressive intentions will have more autonomy to do nasty things, both because the export class is smaller and because higher tariffs supply them with more revenue to fund war.6

Both the initial liberal argument and its subsequent domestic-level offshoots revolve around the idea that trade provides high material benefits to certain groups of people—either the society as a whole or particular vested interests—and war therefore is avoided because of its high opportunity costs, namely, the loss of these benefits. Recently, formal modelers have sought to go after the opportunity cost logic while still upholding the overall liberal insight that high interdependence should tend to move the system toward peace. The essence of their critique is clear-cut. In any situation of asymmetrical interdependence, the high opportunity costs of war should give the more dependent state, state Y, a big reason to avoid war. But the less dependent state, state X, knowing Y’s desire to avoid war, has an incentive to coerce it into making concessions through the use of military threats. Whether interdependence will lead to less militarized conflict or in fact more is thus indeterminate when we consider the opportunity cost reasoning on its own. The modelers agree that state Y will be more peaceful. State X, however, will likely be more aggressive, precisely because of Y’s unwillingness to risk the current benefits of peace.7

In place of the opportunity cost logic, these critics offer another deductive reason for the liberal prediction that trade should be associated with peace. Drawing on insights from the bargaining model of war, they contend that wars are generally the result of the private information that actors have about the resolve of other states—that is, their willingness to pay the costs of war.8 High interdependence helps to foster peace by increasing the number of tools that states have in their toolbox for sending “costly signals” of their true resolve. Leaders of states that are dependent on trade and investment flows can deliberately impose sanctions that hurt their own people, thereby signaling that their nations are willing to suffer high costs to achieve their objectives. This should eliminate any underestimations of their resolve. In an environment of strong commercial ties, therefore, aggressive opportunists in the system will know not to push too hard, lowering the risk of an inadvertent spiraling into war.9

The economic realist argument seeks to turn the liberal perspective on its head. All the arguments we have seen so far can be classified as liberal since, in whatever their form, they begin with the assumption that interdependent actors are interested in maximizing their net material gains/utility and will have good absolute gains reasons not to fight when interdependence is high. Realists reject this starting point. In anarchy, realists assert, leaders must be primarily concerned with maximizing the security of the states for which they are responsible (Grieco 1988; Mearsheimer 1994–95). Given this, interdependence will only increase the chances of militarized conflict and war as interdependent states scramble to reduce the vulnerability that dependency brings. States concerned about security will dislike dependence, since it means not only that access to valuable export markets and foreign investments might be reduced by adversaries bent on hurting their relative power positions but also that crucial imported goods such as oil and raw materials could be cut off should relations turn sour.

Such uncertainty about their economic situations, realists assert, will push great powers to war or the use of military coercion to lower their dependency as well as to ensure the continued flow of trade and investment. As Kenneth Waltz (1979, 106) puts it, while actors in domestic politics have little reason to fear specialization, the anarchic structure of international politics forces states to worry about vulnerability, compelling them “to control what they depend on or to lessen the extent of their dependency.” It is this “simple thought” that explains “their imperial thrusts to widen the scope of their control.” John Mearsheimer (1992, 223) observes that states requiring vital goods, fearing cut off, will seek “to expand political control to the source of supply, giving rise to conflict with the source or with its other customers.”10 The Waltz and Mearsheimer thesis is founded on the assumption, most often associated with offensive realism, that states in anarchy must assume the worst case about the present and future intentions of the other. As such, when states find themselves in situations of dependence, they are forced to grab opportunities to reduce their vulnerability through war, at least when the chance to do so arises at low cost.11

The final group of arguments involves the neo-Marxist theories that link growing interdependence to war. Vladimir Lenin ([1917] 1996) has famously declared that capitalist trading states are more likely to engage in war against peripheral states in order to find cheap raw materials, export markets for their mass-produced goods, and places to invest surplus capital. The competition between capitalist great powers resulting from this struggle for colonial empires will eventually lead to war in the core system.12 Most post-1945 neo-Marxists scholars of imperialism have adopted this reasoning in one form or another.13 At its core, the neo-Marxist logic challenges the liberal domestic-level claim that capitalist sectors and firms dependent on the global economic system have a vested interest in peace. While agreeing with liberalism that such groups are driven primarily by the material gains from commerce, neo-Marxists contend (implicitly borrowing from realism) that the need for secure trade and investment ties makes these groups worry about their future control over their economic partners. Hence, powerful capitalist groups within the state will put pressure on political elites to project military forces into important regions, and use direct occupation or neocolonial coercion to ensure continued trade and investment flows.14

Despite the realist flavor of the neo-Marxist approach, it does differ significantly from economic realism and the theory that I will put forward below. Neo-Marxists see economic elites and interest groups pressuring political elites into war to further their narrow material concerns. Economic realism and trade expectations theory, on the other hand, maintain that political elites are autonomous actors who choose policies based on what is good for the security of the whole state, not based on the greedy interests of a few.15 This distinction in causal logic must be kept in mind when we look at the historical cases, given that neo-Marxism, realism, and trade expectations theory all expect that commerce will lead to war under certain conditions. Because the correlational prediction is frequently the same, the only way to test the superiority of one explanation over the other is to examine whether the specific causal claims of the theories were confirmed by the evidence.

COMMENTS ON THE MAIN THEORIES

The theories we have seen so far are, for the most part, deductively sound. They put forward causal logics that on the face of it sound plausible and could indeed play themselves out in the real world. It seems self-evidently true, for example, that actors that are receiving high benefits from staying at peace will want to avoid war, whether those actors are states as a whole or individual interest groups. Yet it also seems clear that actors that feel vulnerable to the loss of those benefits and the potential impact of large adjustment costs will want to project military power against the source of vulnerability. Both liberals and realists have a point. They just have not specified the conditions under which they might be right. The theory of trade expectations outlined below will help to resolve this problem.

The fact that liberals and realists are both on to something was demonstrated by the very divide that existed in the large-N quantitative scholarship by the end of the 1990s. On the one side, serving as standard-bearers for the liberal cause, were Bruce Russett and John Oneal, two scholars who seemed to show through a number of publications that trade dependence is on average strongly correlated with more peaceful behavior.16 On the other side, in support of realism, Katherine Barbieri (1996, 2002) revealed that when the data from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are included in the large-N analysis, and when different specifications of the key independent variable (trade dependence) are used, interdependence more often than not has led to more conflict and war, not less. This liberal-realist divide puzzled scholars for a few years, until the obvious conclusion began to emerge: interdependence can lead to both peace and war. Because the work of Russett and Oneal as well as Barbieri considered only general patterns and averages across thousands of data points, their analyses, through the use of different time frames and variable specifications, were inadvertently picking up the fact that interdependence, depending on the conditions, can push states to either moderate their behavior or take more aggressive actions.

Over the last decade, this fact has led to a veritable cottage industry of new and more complex large-N analyses, with most of them seeking the holy grail of that extra condition or set of conditions that determine whether interstate commerce is peace inducing or war inducing. Much of this work, as I discuss in chapter 2, has been extremely useful to the field as a whole, and has in the process challenged many of our cherished beliefs about the role of other noneconomic variables. The work of Patrick McDonald (2004, 2007, 2009, 2010) and Erik Gartzke (2007; Gartzke and Hewett 2010), for instance, has demonstrated that trade and investments between nations usually only have a dampening effect on war when those nations are advanced capitalist states. Michael Mousseau (2000, 2003, 2009) and Havard Hegre (2000) have reinforced this finding from another angle, suggesting that it is the overall level of economic development that makes commerce peace inducing. Christopher Gelpi and Joseph Grieco (2003a, 2003b) have argued that trade’s effects are conditioned on the existence of regime type: democracies with high trade are more peaceful, but autocracies are often made more aggressive by trade. Edward Mansfield and Jon Pevehouse (2001) have indicated that trade’s restraining effect on war is conditioned on the existence of regional trade pacts and institutions.17

The statistical work supporting these new findings is solid. Yet as I discuss further in chapter 2, the theoretical arguments used to explain the correlational findings are still underdeveloped and, in the absence of case studies, largely speculative. In short, we still do not know why these correlational results obtain when well-designed statistical studies such as these are undertaken. This chapter will provide this theoretical explanation, and chapters 3–8 will show its veracity through detailed case studies.

Before turning to the trade expectations argument, however, I need to say a word about the two other broad approaches—the signaling argument and neo-Marxism. Unlike the liberal opportunity cost logic and realist vulnerability argument, the deductive logics of both approaches suffer from internal tensions that make them unlikely to have much causal force in the real world. The signaling argument begins with the idea that the more dependent actor, state Y, will be pushed around by the less dependent actor, state X, given that X knows that Y does not want to give up the valuable benefits of peace. Yet the argument then goes on to suggest that because of its high dependence, Y has more tools to use in its effort to make costly signals of its resolve. These two elements work at cross-purposes. State Y may be more flexible in its ability to show its resolve. But it is also less likely to be resolved in the first place, given its fear that a war would end the trade benefits that it currently receives. The net result is a wash: we cannot know ahead of time which of these effects will prevail, even if the reasoning is right about the way interdependence helps the signaling process.18

Neo-Marxism also contains a tension that should limit its applicability. As David Landes (1961) noted half a century ago, the neo-Marxist logic for how capitalism leads to actual imperialist aggression (as opposed to, say, mere gunboat diplomacy) requires three things to be true. First, the business class must be united as a group, or at least have one part of it that is cohesive enough to act as a unit. Second, this class or subgroup within the capitalist economic elite must agree that military aggression against other states is in fact the best means to further its economic ends. Third, the business class or a subgroup within it must have a great deal of influence over the political elites—enough to be able to push these elites to choose war even when the action will cost the lives of thousands or perhaps millions of the nation’s citizens.

Each of these elements is a necessary condition for the neo-Marxist argument to have sway. If any one of them does not hold, the argument should fail to have causal force. And there are reasons to doubt that they will indeed hold. There are few groups other than broad umbrella organizations (for example, the national chambers of commerce) that can bring firms with diverse interests together. Much more likely is the fragmentation of firms into lobbying groups representing particular sectors, such as mining, oil, and manufacturing. Such diverse interests will be unlikely to agree on even a broad policy for tariff reform or infrastructural subsidies, let alone for a policy of war.19 Moreover, the neo-Marxist logic requires us to assume that elected leaders within capitalist democracies will risk the lives of the population—and thus their own chances for reelection—just to satisfy the needs of an especially energized sector of the economy. Such an assumption might work for small-scale actions, such as low-level US interventions during the Cold War (Guatemala 1954, Panama 1989, etc.).20 This book, however, is about wars between great powers or the crises that increase the chance of such wars. And here the costs and risks to the nation are high enough to make almost any politician pull back from the initiation of any war designed solely to protect the parochial material interests of a few. We will see in my empirical chapters that except in a few cases, neo-Marxism provides us with little insight into the causes of great power conflicts.

TRADE EXPECTATIONS THEORY

The trade expectations approach, as I have noted, is designed to resolve the fundamental tension between liberalism and realism, and in doing so, offer a causal logic that not only explains the correlational results of recent large-N analyses but also a vast amount of modern diplomatic history at the same time. It gains its leverage through the introduction of an additional variable—a dependent actor’s expectations of the future trade and investment environment—that determines when high dependence will push states toward either relatively peaceful behavior or hard-line policies and war.21 The introductory chapter laid out the core argument and some of its more important dimensions. My goal here is to show exactly how the argument works and add conceptual depth to the main deductive logic.

The trade expectations argument accepts the liberal point that trade and investment flows can lead to peace by giving states an incentive to avoid militarized conflicts and war. Yet at its foundation, as I stressed earlier, the theory is fundamentally realist rather than liberal. It starts with the assumption that leaders of states whose behavior we are trying to explain are primarily concerned with protecting the long-term security of their countries and that they operate in a realm of essential domestic autonomy. It then asks how any dependent state Y will be predicted to act given changes in the external conditions of its existential situation. The dependent state’s policies, as it seeks to maximize its security, will shift only in response to these external conditions. All unit-level variables within Y that might have salience for liberal and neo-Marxist scholars—including welfare- or profit-maximization drives, pressure group politics, and desires for reelection—are assumed to have no influence whatsoever on state Y’s decision making or behavior.22

Such a theoretical starting point is designed to keep the deductive logic “pure.” That is, it allows us to see how dependent states will operate in response to conditions even when they only want to survive the rough-and-tumble of anarchic great power politics. When it comes to actual cases, of course, the leadership of any particular state Y that we are interested in explaining will have many competing forces working on it, including the factors outlined by liberals and neo-Marxists. By assuming state Y is driven only by rational security maximization, however, we allow a direct test of trade expectations theory’s value versus its competitors: if it has explanatory and predictive power, we should see liberal and neo-Marxist variables having less causal salience in history than those outlined by the new approach. Balanced documentary analysis will undoubtedly reveal that domestic variables within Y sometimes had causal importance in explaining shifts to hard-line behavior across the historical cases. But if factors external to Y usually drove its behavior, and domestic variables are shown to be only occasionally determinative, then the advantage of building deductive theories with an assumption of rational security maximization is demonstrated.23

Political Economy Preliminaries

Before I turn to a detailed analysis of the argument, one question must be addressed up front. If this is a theory of great power politics, shouldn’t we expect that great powers will rarely trade heavily with other great powers or their spheres, and hence that interdependence will fall out as a crucial variable? Neorealists often make the argument that while interdependence is more likely to lead to war than to peace, it is usually not as salient a variable as relative power precisely because great powers have clear reasons not to trade with one another in the first place. This claim is founded on the dual logic that great powers have both relative gains concerns and a fear of vulnerability: they worry not only that they will lose relatively through trade cooperation but also that trade dependence, especially on vital goods such as oil and raw materials, will make them subject to cutoffs and coercive diplomacy down the road.24 As we saw in the introductory chapter, by the way trade works, these two points are almost always at odds with one another. If state Y is getting a large relative gain from trading with state X, then it is also giving X more bargaining leverage in the future, considering that Y has a greater relative need for the continuation of trade and will be more hurt than X by any severing of economic relations. Neorealists are mute regarding how great powers deal with this inherent tension or trade-off. The relatively gaining state is also the most vulnerable one in the relationship. Should Y reject trade cooperation to minimize vulnerability, even though it means giving up the relative gain? Should X reject cooperation because it helps Y grow in relative power, even though it means forgoing a chance to “leverage” Y’s vulnerability for its foreign policy ends?

The fact that such a tension exists helps explain an empirical reality that should make us automatically question the neorealist understanding of international political economy: that great powers in history do indeed trade with each other, and often at high levels. For the fifty years before World War I, for example, the great powers of Europe were regularly each other’s best trading and investment partners, even when they were adversaries on the foreign policy front. Germany traded heavily with Britain, Russia, and even France, and Britain continued strong economic relations with France and Russia after 1860 despite their ongoing colonial struggles in Africa and Asia. Inter-European trade rebounded in the 1920s, and it was only after 1930 that European states retreated into more autarkic realms of imperial preference.25 To be sure, the United States and Soviet Union did think more in neorealist terms during the first two decades of the Cold War, and trade was low between them. Yet as I show in chapter 6, this did not mean that the leaders of the two superpowers were unwilling to discuss much more active economic relations. These conversations even included the possibility of US government funding of Soviet purchases of American goods—surely the ultimate form of relative loss, since the less dependent state is essentially giving away its goods in the short term and receiving back only its own loaned money.

So if the neorealist view of international political economy is shot through with deductive tensions and empirical contradictions, how can we explain why great powers come to depend on each other and yet hold to the realist theoretical foundation at the heart of this study? The answer is surprisingly straightforward, and one that was traced in its outlines three to four decades ago by such realist scholars as Robert Gilpin and Klaus Knorr. Leaders of great powers understand that to sustain a strong level of military power, a state must have a vibrant and growing economy. Most important, leaders know that if other countries are industrializing and improving their technological sophistication, then they must do so too. Yet at the heart of advanced economies are three critical, unavoidable realities or, one might say, principles that push great powers to trade: economies of scale, diminishing marginal returns, and the proliferation of raw material inputs.

When economies of scale are present, as they almost always are with large industrial enterprises, it is necessary—if only to compete effectively with other firms and nations—to invest in large factories and enterprises that can reduce the per unit cost of production. Yet in building such phenomenal productive capability, firms require huge markets for their goods to make a profit, given the large fixed costs of modern industrial operations (“overhead”). Political elites understand this. Hence, it is in the larger interest of the nation to help its best and more efficient producers to find foreign markets for the country’s goods. Because other great powers are necessarily wealthier than less developed states, they have a lot of purchasing power. It makes good economic sense, then—and indeed it is critical to sustaining an advanced economic base—to allow trade to occur with other great powers and not just with small peripheral states. For a leader to deny opportunities to trade with other great powers, especially in multipolar environments of many large states, would be to allow those states that do decide to trade to capture the economies of scale and outperform one’s state over the long term.26

As advanced economies grow, however, there is also a good chance that they will start to experience diminishing marginal returns if they fail to trade extensively. Diminishing returns set in when firms try to expand one element or input into the production mix without increasing all the other elements/inputs simultaneously. With industrialized great powers, the problem is usually with the “land” side of the land, labor, and capital mix: if the country does not have open access to large quantities of the raw materials that go into mass production, then adding more capital (machines) and labor (number of workers and managers) will add to production levels, but at falling marginal rates. Unless there is a technological innovation that helps the country use fewer materials per product or synthesize the needed resources at low cost, the state’s economy as a whole will start to experience the latter part of the famous S-curve—perhaps still expanding in absolute terms, but at increasingly slower rates of growth.27 Since great power politics is a competitive game, this means that states that are indeed able to bring in vast quantities of resource inputs from abroad will gain relative to those that are trying to remain largely autarkic. The needs of survival in an anarchic world will thus push great powers to trade with whomever or whatever can provide them with cheap raw materials. To be sure, colonies and the small states within one’s sphere can sometimes play this role. Yet given the simple fact that raw materials are not evenly distributed around the world but rather concentrated in certain geographic areas, great powers will often by necessity have to trade with other great powers.

It is not just the reality that basic resources are frequently cheaper and in greater supply abroad that forces great powers to trade with other such powers. It is also that as economies increase in sophistication, the types of raw material inputs increase in variety. Consider, for example, the shift to the mass production of cars and airplanes after 1910 and especially after 1920. Even if political leaders only had been concerned about these items for civilian and not military use, they would have had to worry about the ongoing supply of such diverse inputs as nickel, manganese, aluminum, iron ore, and rubber just to get the manufactured goods out of the factory. Then of course there was the massive demand for oil to keep the factories running. Yet the greater the variety of inputs, the more likely it is that their natural source will be found outside the home territory of the great power. Moreover, as the economy grows, the more it will use up any internal sources, forcing the nation to go abroad for its vital goods.28 Neorealists may allege that the system forces great powers to rely on themselves, to remain relatively autarkic (Waltz 1979). Nevertheless, as we can see, the very pressures to maintain a fast-growing and economically advanced economy will typically have the exact opposite effect, forcing great powers to reject autarky and instead favor economic ties with a vast number of suppliers, including other great powers. Thus we can understand why Germany would depend on France for a large percentage of its imported iron ore before 1914, or Japan would accept the United States as its main supplier of oil from 1920 to 1940.

The above economic realities suggest just three of the reasons why great powers may have to trade with other great powers.29 But it is worth remembering that even if state Y tries to reduce its direct trade with state X, it will usually be forced by the above realities into trading with the smaller states within state X’s sphere of influence or empire system. Germany therefore traded extensively with British possessions and dominions prior to the First World War (a situation that got it into trouble, as we will see in chapter 3). And the Soviet Union and its bloc allies, even before the United States opened up more direct trade after 1970, had already been trading heavily with the United States’ Western European allies, often against the wishes of Washington.

We have seen that extensive trade with other major players and their spheres may be essential to maintaining the economic vitality of a great power, even though such trade increases its vulnerability, and hence the fear of cutoff and leveraged coercion. The life of a great power is about trade-offs, and this is one that great powers are frequently willing to make. To stay autarkic when other great powers are increasing their trade ties may reduce the vulnerability that comes with dependence, but it is almost always a self-defeating strategy. Given this, it is not surprisingly that we so often see a high level of intersphere dependence in world history, and why currently the only states that can “afford” relative autarky are dysfunctional failed ones such as Burma and Zimbabwe. China would not be the “new power” that it is today if it had held on to the failed autarkic policies of the Maoist era. Chinese leaders after 1979 were smart enough to see the necessity of trade, even if Waltz (1979) did not.

Theoretical Foundations

The above discussion shows why great powers, notwithstanding neorealist arguments, often become highly dependent on each other. We now need to consider in more detail how trade expectations theory can help to resolve the deductive problems of liberalism and realism as they currently stand. To begin to understand how trade and investment flows might shape the likelihood of war in a dynamic environment, it is best to start with the concept at the heart of our debate: economic interdependence. Liberals and realists both freely use the term “interdependence” to describe this core causal variable. It is important to note, however, that in making their deductive arguments, both derive predictions about behavior from how particular actors—typically nation-states—deal with their own specific levels of dependence.30 This allows both camps to deal with situations of asymmetrical dependence, where one state in a dyad is more dependent than the other. Their predictions are internally consistent, but opposed: liberals assert that the more dependent state in a relationship is less likely to initiate conflict, primarily because it has more to lose from breaking ties; realists maintain that this state is more likely to initiate conflict, mainly to escape its vulnerability.

Despite this common focus on the decision-making processes of the more dependent state, liberals and realists have incomplete notions of what it means to be dependent in the first place. Liberals concentrate on the benefits garnered from trade and investment as states move away from autarky; the opportunity costs of dependence are at most the loss of benefits if trade is ended.31 Realists emphasize something that is downplayed in liberal arguments: that after a state has restructured its economy around trade, there may be potentially large costs of adjustment should trade be later severed (Waltz 1970, 1979). A state cut off after basing its economic structure around imported oil, for example, may be put in a far worse situation than if it had never moved away from autarky in the first place.

That liberals downplay or ignore the realist concern with the costs of adjustment is evident. For instance, Richard Rosecrance (1986, 144–45, 233–36), whose writings on interdependence remain an important foundational statement of liberalism’s theoretical logic, directly tries to refute Waltz’s notion of dependence as a trading link that is “costly to break.” He contends that “to measure interdependence in this way misses the essence of the concept.” His subsequent analysis and supporting appendix underscore only the benefits that states give up if they choose not to trade (his “opportunity costs”), and makes no mention of any potentially severe costs of adjustment.32 It is clear why liberals such as Rosecrance are reluctant to acknowledge realist concerns: to do so would imply that dependent states might be more willing to go to war, as realists maintain, instead of less willing, as liberals argue.

This point highlights the liberal understanding of why wars ultimately occur. For liberals, interdependence does not have a downside that might push states into war, as realists contend. Rather, interdependence is seen to operate as a restraint on aggressive tendencies arising from the domestic or individual level. If interdependence falls, this restraint is taken away, unleashing domestic forces and pathologies that may be lurking in the background.33 Rosecrance, for example, ultimately falls back on social chaos, militarism, nationalist ambitions, and irrationality to explain why Germany in the twentieth century would start two world wars within a generation. Because trade had either fallen (by 1939) or its benefits were not properly understood (in 1914), Rosecrance (1986, 102–3, 106, 123, 150, 162) claims that trade offered no “mitigating” or “restraining” influence on unit-level motives for war. This view fits nicely with the overall liberal perspective that unit-level factors such as authoritarianism, ideology, and internal social conflict are the ultimate causes of war.34 The idea that economic factors by themselves can push states to aggress—an argument consistent with neorealism and my alternative approach—is outside the realm of liberal thought, since it would imply that purely systemic forces can be responsible for war, largely regardless of unit-level phenomena.

It is clear that liberals, by their very way of defining dependence, have made economic ties between great powers only a force for peace and not an explanation for war. To explain what propels an actor into initiating a war, liberals must fall back on unit-level factors. Yet it is equally clear that realists, or at least neorealists, have minimized the positive contribution to a state’s economic health generated by the gains from trade. Trade expectations theory seeks to bridge this divide by founding its analysis on a more comprehensive conceptualization of dependence. It then adds the dynamic element of expectations missing in both liberalism and realism.

Trade expectations theory’s deductive logic, as with liberalism and realism, centers on an individual state’s efforts to manage its own situation of dependence. For the sake of simplicity, I will continue to focus on a two-actor scenario of asymmetrical dependence, where state Y needs trade with state X more than X needs trade with Y. The assumption of asymmetry means that changes in the trading environment are more likely to affect Y’s decision for peace or conflict than X’s. This allows us to concentrate primarily on state Y’s decision calculus, given that it is the actor that most determines the probability of a war between the states (as all our main theories agree).35

If state Y moves away from autarky to trade freely with X, it will expect to receive the benefits of trade stressed by liberals.36 The process of opening oneself to trade leads state Y to specialize in the production of goods in which it enjoys a comparative advantage. Yet this restructuring of the economy can entail enormous costs of adjustment should trade be subsequently cut off, particularly if the state becomes dependent on foreign oil and raw materials that are crucial to the economy’s functioning. Hence, on a bilateral basis, state Y’s total level of dependence can be conceptualized as the sum of the benefits received from trade (versus autarky) and costs of being cut off from trade after having specialized (versus autarky). If a state Y of 100 units of GNP, for example, goes to 110 units after trading with X, but would fall to 85 if trade were to be severed, Y’s effective dependence level is 25 units (110 minus 85). This conceptual move brings together liberal and realist notions of dependence, offering a fuller sense of what is really at stake for state Y in its interactions with state X (and after considering Y’s alternative trade options).37

Yet in choosing between an aggressive or moderate grand strategy, state Y cannot refer simply to its dependence level. Rather, it must calculate its overall expected value of peaceful trade into the future and compare this to the value of the war/conflict option. Benefits of trade and the costs of severed trade on their own say nothing about this expected value. There is where dynamic expectations of the future must be brought in. If state Y has positive expectations that X will maintain free and open trade over the long term, then the expected value of trade will be close to that of the benefits of trade. On the other hand, if state Y, after having specialized, comes to expect that trade will be severed, then the expected value of trade may be negative—that is, close to the value of the costs of severed trade. In short, the expected value of trade can vary anywhere between the two extremes, depending on the crucial factor of a state’s expected probability of securing open trade or being cut off.38

From this, we can see how the new approach leads us to a different set of hypotheses regarding the conditions for hard- or soft-line grand strategies. We can predict that for any given expected value of conflict, the lower the expectations of future trade, the more a dependent state will worry about its long-term security situation, and thus the greater the likelihood that it will choose hard-line policies or all-out war.39 Yet when expectations of future trade are high and improving, the state will feel more confident about its security situation, and be more likely to prefer cooperative policies to conflict and war. Variations across time in the behavior of states, therefore, should be driven by shifts in expectations of future trade environments and not just by changing degrees of dependence.

The trade expectations argument thus provides a distinct departure from the static theories of liberalism and realism. These latter approaches derive their predictions solely from snapshots of a state’s level of dependence at any point in time (even as they provide only a partial conceptualization of this concept). They thereby remain inherently limited in their ability to explain the full scope of historical cases. A critic might counter that liberalism and realism do have at least an element of implicit dynamism to them, since in their empirical analyses liberals and realists sometimes refer to the future trading environment. This may be true for their studies of particular cases. But in constructing their overarching deductive logics, it is clear that the two approaches consider the future only within their ideological presuppositions. Liberals, assuming that states seek to maximize absolute welfare, argue that situations of high trade should continue off into the future as long as states are rational; such actors have no reason to forsake the benefits of trade, especially if defection from a trading arrangement will only lead to retaliation.40 Given this presupposition, liberals can argue that interdependence—as reflected in high trade at a specific moment in time—should foster peace. Realists, assuming states seek to maximize security, maintain that concerns for relative power and autonomy will eventually push some states to sever trade ties. States in anarchy must therefore assume the worst about other actors, including their trading partners. Hence, realists can insist that interdependence, again manifest as high trade at any moment in time, drives dependent states to grab opportunities to initiate war now in order to escape potential vulnerability later (Mearsheimer 1992, 2001; Buzan 1984).

For the purposes of forging strong theories, however, trading patterns cannot simply be assumed a priori to match the stipulations of either liberalism or realism. As the last two centuries have demonstrated, trade levels between great power spheres fluctuate significantly over time. Thus, we need a theory that incorporates how a state’s expectations of its future trading environment—either optimistic or pessimistic—affect its decision calculus for war or peace. This is where the new theory makes its most significant departure. By embedding this dynamic variable into the heart of the theory, the trade expectations logic undermines or qualifies much of the established thinking about interdependence and war. A dependent state’s estimation of its expected value of trade, and in turn the expected value of peace, will be based not on the level of trade at a particular moment but rather the stream of expected trade levels into the future. As I have stressed, it really does not matter that trade is high today, since if state Y knows that X will cut off trade tomorrow and shows no signs of being willing to restore it later, the expected value of trade and thus peace would be negative. Similarly, it does not matter if there is little or no trade at present, for if state Y is confident that X is committed to freer trade in the future, the expected value of trade and peace would be positive.

The fact that the expected value of trade can be negative even if present trade is high, due to low expectations for future trade, goes a long way toward resolving such manifest anomalies for liberal theory as Otto von Bismarck’s scramble for Africa in 1884–85 and Germany’s aggression in 1914. Despite high trade levels between the great powers in both cases, German leaders had good reason to believe that the other great powers were seeking to undermine this trade into the future. Hence, expansion to secure control over raw materials and markets was required for the long-term security of the German nation (see chapters 3 and 8). And because the expected value of trade can be positive even though present trade is low, due to positive expectations for future trade, we can also understand such important phenomena as the periods of détente in US-Soviet relations during the Cold War (1971–73 and after 1985). While East-West trade was still relatively low during these times, the Soviet need for Western technology, combined with a growing belief that large increases in trade with the West would be forthcoming, gave the Soviets a high enough expected value of trade to convince them to be more accommodating in superpower relations. Conversely, the failure of presidents Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy from 1957 to 1962 to make equivalent commitments to future trade with Russia exacerbated superpower tensions at a critical juncture when both sides had reasons to worry about the security of their second-strike capabilities (see chapter 6).

Of course, such examples beg the questions of why less dependent states begin to restrict the trade and investment flows of their more dependent partners despite the risks of military escalation, and why they sometimes try to ease tensions and reduce the likelihood of war by making commitments to future economic interchange. Indeed, the very fact that less dependent states have a major card to play in their pursuit of security—the offering of greater trade to more dependent actors in exchange for nicer behavior by their dependent adversaries—makes one wonder why great powers are not always holding out the carrot of commercial gains to reduce the probability of war. This issue is tied to the question of bargaining brought up in the introductory chapter—namely, why states that need each other for basic necessities and economic growth often cannot find a cooperative deal to help them avoid all the costs of great power war. The next section seeks to explain these puzzles.

Feedback Loops and the Question of Endogeneity

Up until now, this chapter has discussed state Y’s expectations for future trade as though they were largely exogenous—that is, as though they were essentially independent of the interaction between the two states. This may be a reasonable assumption in many situations. State X may have a raw material that state Y needs, for example, but X’s reserves of this vital good are becoming depleted, meaning that X will be less able to trade this good over the long term even if it wants to. States X and Y may also be constrained by external events that force a shift in trading practices. In the late 1930s, for instance, Japanese leaders recognized that American leaders would probably have to cut back on oil and iron exports to Japan as dwindling US reserves were needed to supply a military buildup against Germany as well as help aid Britain and the Soviet Union. Tokyo thus had certain exogenous reasons to be less optimistic about trade flows over the long run.

In many and perhaps most situations, however, leaders recognize that they can affect the beliefs of other actors by their actions. The trade expectations that drive state behavior are therefore rarely wholly exogenous; they can be affected by diplomatic interaction. This can happen in two primary ways. First, state X can send certain signals that help the dependent state Y to form a more accurate and positive estimate of X’s willingness to trade at high levels into the future. Such an updating of Y’s beliefs can lead it to increase its estimate of the expected value of trade, reducing its desire for conflict. Second, and equally important, state Y knows that its own behavior—the level of aggressiveness of its foreign policy—will affect state X’s assessment of Y’s character type: namely, whether Y is a reasonable and moderate actor, or one that is inherently hostile for security- or nonsecurity-driven reasons. This assessment will of course tend to shape X’s willingness to commit itself to future trade with Y. After all, if X comes to think of Y as an aggressive actor bent on expansion, X will be less inclined to want to trade freely with Y, especially if that trade is only facilitating Y’s ability to expand through a relative gain in power or through a larger absolute capacity to project power abroad.

This leads us directly to a consideration of the trade-security dilemma briefly described in the introductory chapter. At the crux of the trade-security dilemma is the problem of incomplete information—that is, the difficulty both states have in knowing the character of the other great power. In modern game theory, incomplete information has to do with the other’s current type along with its incentives to misrepresent who or what it is. Thus in the popular bargaining model of war, for example, uncertainty in the model typically revolves around the inability of state Y to know X’s “resolve” and vice versa—in other words, Y’s and X’s present willingness to take on the costs as well as risks of war should crisis escalation actually take both actors over the brink. Through such costly signaling measures as mobilization, public stands, and alliance formation, leaders on both sides can communicate their true characters, thereby helping to reveal a bargaining space that can lead to a compromise deal before war breaks out. If actors prove unable to signal their resolve, war can break out through one or both sides’ belief that by pushing both actors further out on the slippery slope to war, the other will concede to its demands (will “back down”).41 Other scholars extend this work to the efforts of states to signal their current military intentions, as opposed to resolve per se.42

From a dynamic perspective incorporating expectations of the future, though, this is a quite-limited view of how great power politics actually works. There are two other forms of uncertainty about character type that are typically much more problematic and much more likely to lead to war. The first is the uncertainty that X and Y have about the other’s future military intentions—namely, whether the other will have a strong desire to attack it later, perhaps many years down the road. The second is the uncertainty that X and Y have about the other’s future willingness to trade at high and largely unrestricted levels. Here the concern is not that the other will necessarily attack me but instead that it will so constrain my growth through economic sanctions that my country will fall by the wayside, and then be subject to the slow yet steady loss of its territory and sovereignty. This second uncertainty is clearly related to the first, since if the other is deliberately causing me to decline, there is probably a higher chance that it intends to invade later, or at least carve off key pieces of my territory or sphere for itself.

In such an environment of future uncertainty, states will be looking for signs that the other is committed to being a moderate and reasonable actor into the future. If state Y is the more dependent state in the relationship, for example, then it will be keenly attentive to signs that state X is either willing to keep the current high levels of trade and investment going, or if commerce is currently restricted, that it will be likely to open it up over the short and medium terms. Yet as I have stressed, state Y, by the very nature of its higher economic needs, is the state that is almost certainly getting the relative gain from more open trade and investment flows. Thus state X will be looking for signs that state Y, as it grows and develops through the trade relationship, will continue to be a moderate great power with little desire to expand against X’s territorial interests.43

This discussion immediately brings to the fore the pervasive reality of the commitment problem in international relations: the difficulty actors have in anarchy of promising now to be nice later, given that there is no higher authority to enforce the promises and prevent defection.44 As Robert Powell (2006) has demonstrated, in an environment of dynamic power change, the commitment problem can lead to war even when there is complete information about the other’s current type—that is, even when all the uncertainties about resolve are cleared up and actors know exactly whom they are dealing with in the present moment. For Powell, it is a concern about what the rising state will do in the future, after it has grown in power, not incomplete information in the present, that leads to war.

Powell’s argument nicely captures one dimension of the problem of relative decline that hangs over international politics. Yet the commitment problem is only one aspect of what in reality is the much deeper “problem of the future” (Copeland 2011a). The commitment problem, in formal terms, is about state Y’s leadership’s inability to convince X that Y will not defect later from promises made today (and vice versa). But what X is worried about is not just that Y’s current leadership might have a change of heart later once Y has more relative power. State X is also worried that Y might have a change of leadership through elections, coups, domestic instability, and the like that lead the new leaders in Y to adopt very different policies. This is the well-known problem of the changeability of actor type—the fear of backsliding and revolution—that leads realists to stress states’ uncertainty regarding future intentions.45

The problem of the future is even more potentially profound than that, though. State Y’s very growth through the economies of scale that trade engenders can also speed up the depletion rate of its internal resources, creating a positive feedback loop that forces Y to become even more dependent on outsiders merely to keep the industrial machine rolling. China over the last decade has experienced this problem, just as Germany did after 1890. Because the incentives that state Y has to project military power in order to protect trade access routes change as trade dependence grows, state Y may have a difficult time credibly convincing X that it will indeed be moderate at time t +10 or t +20, even if there is no question that state Y is indeed moderate now (time t). In addition, as I discuss below, states X and Y may have difficulty committing to cooperative policies simply because they remain uncertain about the future stability and character of important third parties.

The problem of the future in all its dimensions is what makes the trade-security dilemma such a complex and enigmatic phenomenon of great power politics, and such a difficult phenomenon to understand theoretically. To avert the outbreak of a trade-security spiral that can undermine dependent state Y’s expectations of future trade, Y has to convince X that it will most likely remain a moderate state over the long term if it is going to make the other lean toward an open trade policy. Yet because anarchy does make states want to prepare for unexpected events, Y’s efforts to increase its power projection capabilities can undermine the other’s confidence in Y’s future type and start the trade-security spiral rolling. State X, on the other hand, will know that trade sanctions against Y can cause it to become more hostile. This means that X, all things being equal, would like to convince Y that it will in fact remain a reliable and open trade partner into the foreseeable future. But state Y knows that X also has an incentive to cut Y off later after Y becomes overly dependent or at least to use its economic leverage to coerce Y into concessions Y has no interest in making.

What seems clear in all this is that states in international relations face tough trade-offs all along their historical paths, and that a leader’s decision to lean toward either hard- or soft-line policies involves a balancing of many different factors. Offensive realism tries to ignore the trade-offs by its simplifying stipulation that states must calculate according to worst-case scenarios. States that assume worst-case do not trade with each other, and if they do happen to become dependent (for reasons unexplained), then they are forced to grab any and all opportunities to expand through military power to reduce their dependence. While offensive realists rightly emphasize that dependent states have to worry about future trade access, history shows that they are off the mark when it comes to their prediction that great powers will not trade and will constantly grab opportunities to expand. Indeed, the very fact that for long stretches of time great powers trade heavily with each other rather than simply expanding their territorial spheres shows that they are able to “trust” the other’s type to at least some degree—that they are not assuming the worst.46

This is where my argument fuses defensive realist insights with an essentially offensive realist baseline. Offensive realists are correct to stress that anarchy forces actors to worry about the future power and intentions of others. Defensive realists, on the other hand, are right to assert that states think in probabilistic terms, looking at the likelihood of the other being nasty rather than nice in character as opposed to simply presuming it is the worst.47 Defensive realism allows us to explain why purely security-seeking great powers in anarchy might still be able to sustain high trade levels with other great powers, even though all of them have reasons to worry about the future. These great powers are making trade-offs and are leaning, at least in the short and medium terms, toward the soft-line end of the spectrum. They are engaging in trade cooperation to help build their economies while recognizing that such cooperation, if underpinned by positive expectations of future trade, is helping to stabilize the peace. They are also trying to signal that their characters are moderate so that the other side will have at least a modicum of confidence in their future behavior.

What is still not clear, however, is why a stable trading system between the great powers would ever break down. That is, why would either state X or Y decide to start inclining more to the hard-line end of the spectrum despite understanding—as my rationalist logic assumes they do—that such behavior poses risks of trade-security spirals and ultimately war? This is where exogenous factors outside the control of the political elites in both X and Y play their determining roles. My interest is in explaining the behavior of the more needy state in any relationship, so I will continue to assume that dependent state Y is a rational security-maximizing state whose leaders are unaffected by any domestic-level pressures and pathologies, and thus alter their behavior only in response to changes in either X’s behavior or Y’s external conditions (a non-trade-related fall in power, for example). This means we need to focus on how factors exogenous to X’s leadership are affecting X’s ability and willingness to keep trade relations with Y open and unrestricted.

There are six primary factors that can change X’s calculations of the trade-off between building a reputation as a reliable trade partner (at the cost of giving Y a relative gain) versus reducing trade with Y to curb its economic growth (at the risk of hurting Y’s confidence in X as a trade partner and increasing the chance of a trade-security spiral to war).48 Three of them involve various dimensions of the problem of third parties mentioned above. The first is the degree to which third-party concerns constrain X’s ability or strategic incentive to trade freely with Y into the future. If state Y is posing a threat to state Z, and X’s leaders are determined to help Z survive, then X may reduce its trade with Y in support of Z. As I show in chapter 5, President Roosevelt recognized in 1941 that he could not restore open trade to Japan if that increased the chance of Japan attacking the Soviet Union. Roosevelt needed to keep Russia strong in order to defeat the main threat to world peace, Hitler’s Germany. To avoid having Russia weakened by a two-front war, he maintained tight sanctions against Tokyo to reorient Japan southward and reduce its fighting power. A US-Japanese war was the result. In situations such as this, we can certainly ask why it was that state Y was targeting Z to begin with. In terms of understanding Y’s ultimate attack on X, though, Y’s declining trade expectations due to X’s behavior can take us a long way toward an explanation.

The second exogenous condition shaping X’s trade policy toward Y is the level of domestic instability in small third parties that both Y and X need for their ongoing economic viability. If internal problems within small state F cause state X to intervene to reestablish order, this can cause Y to worry about its future access to F. The formal occupation of F by X, or even simply the informal projection of X’s power into F’s domestic politics, can make dependent state Y believe that F will have to reorient its trade policies away from Y and toward its new great power protector, state X. Throughout the nineteenth century, for example, Turkey had periodic internal crises caused by revolts within the European part of its empire. In many of these crises, Russia feared that it might lose its commercial and naval access through the Turkish Straits if other powers such as Austria and Britain moved in to control the Balkan states. Russia’s efforts at power projection in turn troubled the other great powers of Europe, leading to destabilizing interstate crises and one large-scale war (1853–56). Domestic problems within small third parties also created the context for the imperialist scramble for Africa in the early 1880s: unrest along the Gold Coast and in North Africa encouraged France to push harder for formal control, which in turn led Britain to intervene in Egypt when civil strife broke out there. The Boer War of 1899–1902 was also partly sparked by unrest in third parties, as was the spiraling hostility between Washington and Moscow in 1943–45 that led to the Cold War.

The third exogenous factor is simply the unit-level drives of a third-party great power, state Z, whose actions against small state F cause X to intervene, which then forces dependent state Y to act. Italy after unification had strong nationalist reasons to carve out a small empire in northern Africa. When it readied itself to jump on an unstable Tunisia in 1881, the French felt compelled to jump first. These actions convinced Britain and then Germany that they, too, must reluctantly scramble for pieces of African territory or risk being left out of the game. Note that while domestic-level variables in the third-party great power start the ball rolling, our key players X and Y turn to imperialism not because of their own unit-level pathologies but instead because of their perceived need to protect their trade and investments abroad.

The fourth factor driving X’s trading behavior is Y’s overall level of economic growth, either because of Y’s sheer economic dynamism or because of the relative gains that Y can accrue through trade. State X may be willing to allow Y to grow for a while, especially if state Y starts from a low position in the relative economic power hierarchy. But if state Y can sustain its strong growth trend year after year, Y’s economic growth will start to pose an increasing threat to X, especially if it is being translated into increasing military power. And if X’s leaders come to believe that Y will rise to a point of dominance simply through peaceful engagement, they will be more inclined to turn to more restrictive economic measures to reduce or contain Y’s growth, despite the risks of setting off a trade-security spiral that increases the probability of war. In this sense, the level of asymmetry of dependence between X and Y can act as a crucial shaping force in X’s behavior: if Y gets much more out of the economic relationship than X, then X is not only more inclined to worry about long-term relative loss through continued trade but also sees that it will pay a lesser cost in restricting X-Y trade. The increasingly harsh economic restrictions imposed on the Soviet Union, beginning in 1945, illustrate both of these mechanisms. The US government had good reason to believe that the Soviet Union would grow rapidly after World War II even without trade. Yet it clearly understood that US-Soviet trade, given Moscow’s need for advanced technology, would make Russia’s relative economic rise even more rapid (chapter 6). French and British fears of continued German growth after 1890 also fit this pattern (chapter 3).49

The fifth factor involves the depletion of raw materials within X’s sphere that makes X not only less able to supply Y with such vital goods but also may encourage it to compete with Y for control of third parties.50 The primary example in the case studies is Roosevelt’s recognition in 1943–44 that with US oil supplies running out, the United States had to start intensifying its competition with Russia over dominance in Iran and the Middle East more generally. This factor captures an aspect of the economic realist logic: states that anticipate future dependency on key resources will begin to maneuver now for position, and that maneuvering can cause current trade partners to worry. The realist focus, however, is on X potentially going to war because of its expected future dependency. My focus is on X’s incentive to restrict other states’ access to resources and how that reshapes the expectations of a currently dependent state, Y, when it considers its own future.

Sixth, and finally, X’s leaders may be constrained from trading freely with Y by an exogenous factor arising from within their own state. In particular, X’s executive branch may keenly want to increase trade with Y, but find that the legislative branch is making this impossible. The classic case is US-Soviet relations from 1971 to 1975. Through linkage agreements in 1972, Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger were able to buy Soviet cooperation on a number of issues by extending US trade credits and promising more open trade. Unfortunately, the US executive, in the wake of Watergate, subsequently found itself unable to implement the policy that it wished to undertake: the US Congress negated Nixon’s détente policy through a series of amendments that undermined Moscow’s new, more positive expectations for future trade. We also saw a similar problem for the US executive arise with the passing of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, a legislative action that damaged Japanese confidence in the United States as a trading partner and helped usher in a decade of conflict in East Asia.51

The above exogenous factors can work together or independently to constrain state X’s ability or willingness to trade openly with state Y, thereby setting off a trade-security spiral that can lead both nations into conflict. These factors help us explain theoretically why states with no desire for war may still be unable to locate a bargain that helps them to avoid it. In their absence, however, long-term cooperation can obtain, as long as actors have reason to believe that their concerns regarding others’ commitments to trade and peace in the future are not as problematic as the invoking of a trade-security spiral due to overly assertive policies now.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT AND THE COMPETING HYPOTHESES

This chapter has added flesh to the bare bones of the argument laid out in the introductory chapter. We have seen that to explain fully the relationship between interdependence and war, we must move away from the static models of the traditional literature. It is a dependent state’s expectations of the future economic environment that determines whether its policies will be moderate or hard line, peace inducing or war inducing. Yet since expectations of future trade are often also shaped by the behavior of the actors themselves, we need to specify exactly what sorts of mechanisms are likely to keep great powers on the soft-line end of the spectrum—trading relatively freely across their spheres and avoiding spirals of hostility—and what factors are likely to drive them toward conflictual actions and ultimately war.

Figure 1.1 provides a diagrammatic summary of the basic causal logic of the trade expectations argument. As with both liberalism and realism, the analytic focus is on explaining the behavior of the more dependent state in a relationship—in this case, state Y. It is state Y’s behavior—either soft or hard line—that shapes the probability of war within the dyad. Building on the insights of realism, the trade expectations model maintains that state Y’s policies will be a function of its evaluation of its overall security situation and, most important, estimates of its long-term power position in the system.

This is where state Y’s dependence level and expectations of future trade play their main role. If Y’s leaders need access to the other’s sphere for raw materials, investment income, and markets, and if they have reason to believe its leaders will help facilitate that access into the future, then Y’s policies toward X should be quite peaceful. State Y, anticipating the future stream of benefits, will want to avoid jeopardizing the relationship via hard-line actions that might raise the other state’s mistrust of its future intentions. But if Y’s leaders see X cutting Y off from access to X’s sphere, or have reason to think that X will do so in the future, then the policies of Y will likely turn nasty. State X’s restrictive actions, by reducing current benefits and imposing costs of adjustment on Y’s economy, can cause Y to decline in economic power relative to X. If such decline kicks in, then Y’s leaders have an increased incentive to launch a war against X’s sphere to reestablish economic access and stabilize the state’s power position.

International politics, though, is not simply a matter of responding to expected trends on key economic and power variables. It is also an ongoing bargaining game of give-and-take, gesture and response. States recognize that their soft- and hard-line behaviors send signals to other actors about their levels of commitment to moderate future behavior as well as open trade. State X’s leadership will be watching Y’s behavior for signs that it is an undependable state that might pocket the benefits of trade and use them for future aggression. Part of what drives X’s economic policies toward Y, as figure 1.1 shows, is therefore X’s evaluation of Y’s character based on the latter’s past behavior. If X’s leaders evaluate that character negatively, then they may start to restrict Y’s access to resources, investments, and markets. Such moves could easily kick in a trade-security spiral, whereby X’s new, more restrictive posture on trade and commerce leads Y to undertake more assertive foreign policies against the former’s sphere or third parties, which in turn leads X to further restrict Y’s ability to trade freely. This self-reinforcing feedback loop could ultimately lead Y to initiate war, either against state X directly or smaller states within its sphere.

We have also seen that the awareness of leaders of the deleterious effects of the trade-security spiral should give both sides reasons to avoid overly provocative policies. Why, then, might either X or Y start to shift toward the hard-line end of the policy spectrum? One possibility is that Y observes that the general trade environment is now no longer working in its favor. Japan after 1929, for example, faced a situation where all the major powers were retreating into increasingly closed-off economic spheres. It is thus not surprising that Japanese expectations of future trade turned pessimistic. Yet in analyzing the X-Y relationship, we must focus more specifically on the factors that might cause X to reevaluate its own weighing of the relative benefits and risks of open trade with Y. This chapter laid out six main factors that can push X to restrict Y’s trade access: concerns about Y’s designs on a third-party great power; domestic instability in small states and X’s need to intervene; the drives of a third-party great power against a small state that forces X to act; X’s fear of Y’s overall economic growth; X’s depletion of key raw materials and its need to compete for future control of these resources elsewhere; and legislative resistance to the economic policies of X’s executive branch.