Quantitative Analysis and Qualitative Case Study Research

OVER THE LAST THIRTY YEARS, the study of economic interdependence and conflict has been driven empirically by scholars who use exclusively large-N quantitative methods to test the various competing hypotheses. In fact, one would be hard pressed to find more than a handful of scholars who have ever presented even a single in-depth case study based on the diplomatic-historical evidence, let alone attempted a detailed cross-case analysis of the competing arguments.1 The vast majority of the empirical studies focus simply on the statistical findings generated by elaborate mathematical models, and thus offer little sense of how the results might apply to particular cases or periods. The causal mechanisms that lead to peace or war will be inadequately understood if this is our sole or primary methodology, given that quantitative methods are inherently about correlations and associations between variables rather than causality per se. This book’s larger purpose is to rectify this situation. Starting in 1790 with the onset of the modern postrevolutionary period of world history, the book will plunge into the documentary evidence to show the relative salience of international economic variables for the onset of conflict between the great powers. Detailed case analysis will allow us to determine to what degree great power interdependence and commercial expectations actually drive world history relative to other potential causal factors, and when they do, which of our particular economically based theories is best supported.

Yet this does not mean that the quantitative analyses do not have an important place in the study of interdependence and war. Recent studies certainly have offered a number of new and critical insights into the impact of trade and commerce on international conflict, insights that have the potential to reorient the whole field of international relations. Most important, they reveal that key variables such as trade dependence and the level of mutual democracy do not, on their own, have consistently significant or predictable effects on the probability of interstate conflict. Their effects are conditioned on the presence of other variables such as development levels, the intensity of contracts, and the role of institutions and high-level contacts that determine when as well as to what extent dependence and democracy shift the likelihood of militarized conflict and war. Such findings, as we will see, undermine our confidence in the foundational assertions of liberals that commerce always tends to reduce the probability of conflict or that higher degrees of shared democracy necessarily create zones of “democratic peace.” The takeaway point from these recent large-N studies is a startling one for modern liberals: commerce not only can cut either way—pushing states toward peace or greater conflict—but the causal role of regime type can be often overridden by the powerful impact of trade and financial flows.

Subsequent chapters, through in-depth case study analysis, will show the strong historical support for these dramatic findings. I will demonstrate that the effect of economic interdependence is conditional on the expectations of future trade and financial flows that shape leaders’ confidence in their long-term power positions in the system. Indeed, as the recent quantitative studies confirm, expectations of the commercial environment can drive foreign policy behavior even when trade levels between states are low or nonexistent; it is leader expectations of the future combined with the underlying need for future commerce that drive state actions. The case studies also reveal just how weak regime type is as a causal variable that pushes states into war. Even for what should be “best cases” for the liberal claim that states with pathological goals and domestic structures are the initiators of war when trade is low, the documentary evidence indicates that the external pressures of a state’s economic situation are almost always more influential in the decision for conflict than unit-level propelling factors. As we will see, quantitative scholars nicely support this finding by observing that the likely basis for any democratic peace between modern liberal-democratic states is not domestic institutions or moral constraints but rather the economic structures that such states usually possess. Because large-N studies reveal correlations not causation, the exact causal mechanism that explains how and why these structures lower the risks of conflict is still up for debate between quantitativists. I will argue that the trade expectations logic provides the only coherent explanation across the diverse array of models presented in the quantitative literature.

The second half of this chapter discusses the research method used to explore the qualitative-historical cases and summarizes the findings of the six historical chapters. I look at a new approach to doing case study research when one is dealing with rare events. The phenomena I am studying in this book—destabilizing great power crises and war along with the changing probabilities of their onset across time—are fortunately rare occurrences in modern world history. Their rarity is a reflection of the complex number of factors that must come together before the events can arise. In-depth qualitative research has the advantage over quantitative methodologies in that it can unpack the exact mix of causes that go into particular cases. Yet traditional ways of doing case study work have tended to suffer from problems of selection bias and an inability to generalize beyond the cases considered. I show how the examination of the essential universe of cases across a bounded time frame and for a clearly defined set of actors can overcome these problems while focusing our attention on what is ultimately of most interest: how frequently it is the case that the factors of a particular theory are able to explain the phenomena in question, and with what degree of salience. True progress in international relations requires that scholars actively debate specific cases in order to establish general agreement as to how often and how well theories work across space and time. Toward the furthering of this end, the last part of the chapter provides a brief summary of the results of the next six chapters. This summary highlights not only the surprising salience of commercial factors in the onset of great power crisis and war but also that the trade expectations argument outperforms both the liberal and economic realist ones in explaining how such factors have shaped the likelihood of war and peace since 1790.

THE CONTRIBUTION OF QUANTITATIVE STUDIES

From the early 1980s to the late 1990s, the quantitative study of economic interdependence and war revolved around one simple question: whether higher levels of interdependence lead to a greater or lower probability of militarized conflict. Little effort was expended to explore whether the effect of commerce was conditioned by the presence of other important variables.2 In the initial stages of any new quantitative investigation, it makes sense to express the key research question in such straightforward terms. After all, one is trying to figure out whether the new variable of interest—in this case, economic interdependence—has any statistically significant effect relative to established causal variables (typically represented as control variables within the analysis), and if so, whether that effect is in the positive or negative direction.

Because of the simplicity of their setups, however, these early studies were bound to come up with conflicting or overly general answers that left the field more confused than enlightened. Oneal and Russett led the liberal charge, showing that increasing interdependence (typically measured by trade over GDP) is associated on average with a reduction in the likelihood of militarized interstate disputes and war. They were also able to support the larger liberal proposition that mutual democracy and the presence of international institutions, in conjunction with economic interdependence, all help to improve the chances for peace, with each element contributing a statistically significant benefit to the overall mix.3 Barbieri challenged Oneal and Russett’s quantitative results regarding interdependence. Starting from a largely realist framework, she demonstrated that with different conceptualizations of the key independent variable, one could show that interdependence either had no statistically significant effect on international conflict or in fact increased its probability rather than lowering it, as liberals assert.4 The decade of the 1990s ended with a fierce and largely inconclusive debate around which side, liberal or realist, was correct.5

By the turn of the new century, a host of scholars had come to the obvious realization that correlations between any single variable such as economic interdependence (however it is measured) and militarized conflict show only average relationships. In simple quantitative models, a great many of the data points will fall far from any “regression line,” indicating that a large number of the individual cases may be exhibiting the opposite causal relationship from what any average across the data points would seem to reveal. If that were the case here, then interdependence could be cutting both ways, sometimes leading to more conflict and sometimes to less conflict. Everything would then depend on the specification of further conditions that interact with economic interdependence to determine when trade and financial flows hurt or improve the chances for peace. Yet the initial quantitative models, because they were simply adding economic interdependence measures to the established host of largely noneconomic control variables, were not able to capture these conditional relationships.

Interactive variables were needed to transcend the dead end reached in the initial liberal-realist debate of the late 1990s. Simple quantitative models examine whether causal variable A and causal variable B have independent and additive effects on event E. In more complex models with interactive variables, though, an interactive term A × B is introduced to see to what extent A and B potentially feed off one another synergistically to determine E’s value across space and time. Depending on the signs of the coefficients, the inclusion of an interactive term, when read in conjunction with A and B on their own, can reveal conditional relationships that remain hidden in simple additive models (Friedrich 1982; Braumoeller 2004).

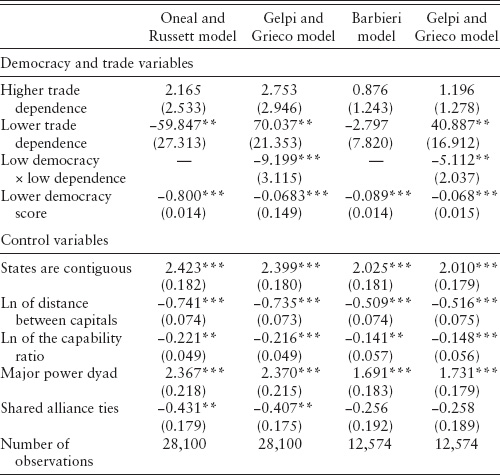

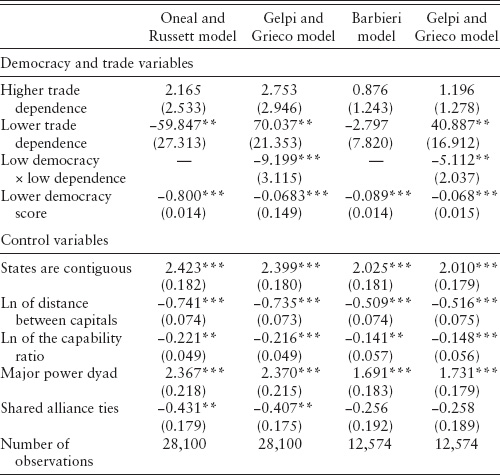

One of the first important contributions in this regard was Gelpi and Grieco’s (2003b, 51) reexamination of Oneal and Russett’s and Barbieri’s data sets, this time with an interactive term capturing the possible synergy between regime type (level of mutual democracy) and economic interdependence. Using a logit estimator designed to analyze rare events data, Gelpi and Grieco first reproduced the basic results of Oneal and Russett as well as Barbieri—namely, that interdependence either has a statistically significant negative effect on the probability of a militarized dispute (Oneal and Russett) or no statistically significant effect (Barbieri). Their results are reproduced in columns 1 and 3 of table 2.1. They then went on to show how the inclusion of an interaction term between regime type and interdependence dramatically changes our understanding of the variables (columns 2 and 4).6 When the interactive term is included, the trade dependence variable on its own stays significant, but switches from a negative to positive coefficient. The coefficient for the regime variable, democracy, remains, as liberals would expect, negative and significant, while the coefficient for the interaction term is also negative and significant. The implications of these results are profound. They suggest that interdependence only helps to reduce the probability of military conflict when both states are strongly democratic. When the level of joint democracy is low, however, growing interdependence can actually increase the risk of conflict.

Something in the simple liberal version of the commercial peace is clearly not quite right. Trade may reduce the probability of war for strong democracies. But between autocratic states, it makes conflict more likely, not less likely. Of course, as a set of computer-generated large-N correlations, Gelpi and Grieco’s results beg the obvious question: Why might this be so? Drawing on a fusion of classical liberal and selectorate theories, Gelpi and Grieco (2003b, 52–54) hypothesize that democratic leaders are more responsive to the larger population, and thus are sensitive to the opportunity costs of disrupted trade. Authoritarian leaders are less sensitive to these opportunity costs, and hence less constrained from initiating crises and wars.7 There is something incomplete about this explanation, though. While it might capture part of the reason why democratic states with high trade are loath to fight, it is less than satisfying as to why authoritarian states with high trade are more likely to fall into conflict than authoritarian states with low trade. Gelpi and Grieco’s explanation is based, like most liberal arguments, on the constraints provided by trade that hold states back from fighting. Democratic leaders may be more sensitive to these costs and therefore less desirous of conflict when trade is high. But by their own logic, authoritarian leaders either should be slightly less inclined to conflict (if at least somewhat sensitive to public opinion) as trade rises or unaffected by trade levels altogether. Why they might be propelled into conflict because of increasing trade is left unexplained by such an argument.

TABLE 2.1 Gelpi and Grieco’s Results on the Role of Democracy and Interdependence

(Dependent Variable: Onset of a Militarized Interstate Dispute)

Note: Gelpi and Grieco 2003a, 51, with some rounding of numbers and their four “Peace Year Splines” removed for space considerations. The number of observations is lower than the other works studied in this book, given Gelpi and Grieco’s use of rare-event logit analysis. Original note in Gelpi and Grieco (ibid.): Standard errors for coefficients appear in parentheses. Huber-White robust standard errors allowed for clustering on each dyad. All tests for statistical significance are two tailed. *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Gelpi and Grieco (2003b, 52, 54) are not unaware of this problem. Yet to deal with it, they simply assert that realists must have it right when it comes to authoritarian states—that is, that increasing commerce heightens their senses of vulnerability to any cutoffs in trade. This is an ad hoc fallback argument that does not tell us why realism only applies to authoritarian states or under what conditions a realist-like logic might apply to democracies as well, thereby offsetting the opportunity cost reasoning. A more plausible conceptual approach—one that would offer a consistent theoretical argument across all dyads—would start with the idea that it is the economic characteristics of democracies and authoritarian states, as opposed to their domestic institutional or moral qualities per se, that drive their likelihood of military conflict.

A trade expectations approach, for example, would interpret Gelpi and Grieco’s findings as follows. Democracies, because of their liberal economic structures and ideologies, are generally more oriented to free trade—or at least freer trade—than authoritarian states. As such, when two democracies have high trade they are likely to feel confident about the long-term prospects for open commerce. This should hold even when the tariffs and nontariff barriers to trade are occasionally raised, say, to punish other states for what are judged to be unfair trade practices in certain sectors. But if authoritarian states are seen, because of their economic orientations, as less committed to long-term “open-door” policies, increasing levels of trade dependence can actually increase the probability of militarized conflict. Uncertain or pessimistic trade expectations would push one or both sides to turn to military force to protect access to raw materials, investments, and markets. Adverse trade-security spirals might result that would only exacerbate mistrust and hostility. The democratic peace, in this reading, is therefore really an economic peace, based on the largely free-trading orientation that most democracies adopt. It is positive expectations about the future commercial environment that leads two democracies with increasing trade dependence to have a lower risk of a militarized conflict. And it is more pessimistic expectations about future commerce that makes dyads with authoritarian states more conflict prone.8

Studies by Hegre, Mousseau, Gartzke, and McDonald point strongly toward the idea that it is the economic characteristics of certain states—and what these characteristics say to the outside world—that really matter, and not their legislative or moral aspects per se.9 Hegre and Mousseau, in separate work, show that the effects of interdependence and those of joint democracy, respectively, on the likelihood of militarized conflict are conditioned by the levels of development that two states have reached. When statistical models that include interactive terms for interdependence and development as well as democracy and development are tested, the simple arguments for the liberal commercial peace and liberal democratic peace are overturned or highly qualified. Hegre (2000, 16) demonstrates that when the interactive term of interdependence × development is added to the baseline model, the coefficients for the interactive term and for the development variable on its own are significant and negative. The interdependence variable on its own, however, while it remains highly statistically significant, reverses its sign from negative to positive. This indicates that trade dependence only helps to reduce the likelihood of military conflict when both states are highly developed nations. When there is a low level of development between one or both states in a trading relationship, higher levels of interdependence can actually increase the probability of conflict. These results are reproduced in table 2.2.10

Mousseau’s (2003, table 1, 490, and table 2, 495) work is focused more on the possibility that it is the democratic peace, rather than the liberal commercial peace per se, that is conditioned by the level and nature of development. Nevertheless, his findings have dramatic implications for the study of economic interdependence and war. In the initial presentation of his research, he shows that once one introduces an interactive term for democracy and development, the coefficient for joint democracy goes from being negative to positive, even as the coefficient for the interactive term is negative. This suggests that joint democracy only helps to reduce the risk of conflict when both actors are developed nations. When development levels are low, joint democracy can actually increase the likelihood of a militarized conflict—a result that Mousseau confirms in a later article coauthored with Hegre and Oneal.11 All this builds the case for the intriguing proposition that the democratic peace is really an economic peace, not a political one.

TABLE 2.2 Hegre’s Results on the Role of Development and Interdependence

(Dependent Variable: Onset of a Fatal Militarized Interstate Dispute, 1950–92)

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Development and trade variables |

|

|

Interdependence |

−0.13*** |

0.87*** |

(residual from gravity model of trade) |

(0.39) |

(0.29) |

Development: GDP per capita |

−0.48*** |

−0.70*** |

|

(0.18) |

(0.16) |

Interdependence × development |

— |

−0.14*** |

|

|

(0.04) |

Control variables |

|

|

Two democracies |

0.28 |

0.34 |

|

(0.40) |

(0.39) |

Two autocracies |

0.019 |

−0.045 |

|

(0.26) |

(0.25) |

Missing regime data |

−0.91 |

−.076 |

|

(0.78) |

(0.76) |

Continguity |

3.03*** |

3.02*** |

|

(0.35) |

(0.34) |

Alliance |

0.06 |

0.007 |

|

(0.25) |

(0.25) |

One major power |

−0.14 |

−0.001 |

|

(0.37) |

(0.36) |

Two major powers |

0.52 |

0.47 |

|

(0.53) |

(0.53) |

Number of observations |

266,094 |

266,094 |

Note: Hegre 2000, 16, with size asymmetry and peace history control variables removed for space considerations. Models 1 and 2 above correspond to Hegre’s models 1b and 1c, respectively. Standard errors for coefficients appear in parentheses. All tests for statistical significance are two tailed. * p < 0.10; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

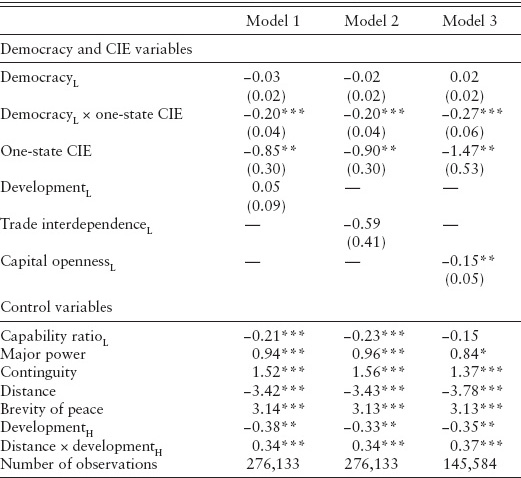

In his more recent work, Mousseau (2009, 61) seeks to unpack the causal reasons for why development, in correlational terms, seems to have these strong conditioning effects. He suggests that developed states are more able to foster what he calls contract-intensive economies (CIEs): economies where transactions are based around impersonal contracts backed by effective legal systems rather than on traditional social connections and personal contacts. When firms are conducting business within and between such CIEs, he argues, they are able to overcome problems of trust regarding the other’s true commitment to carrying out its expressed obligations into the future, problems that might otherwise impede their willingness to go forward. As he summarizes it, CIEs “foster the expectation that strangers will fulfill their contractual commitments,” implying that states with established CIEs will have “higher levels of impersonal trust than other nations.” In his empirical tests, the interactive term, joint democracy × CIE, is strongly significant and negative, while the coefficient on the joint democracy variable, depending on model specifications, is either negative or positive, but never reaches a level of statistical significance. This implies that joint democracy is only peace inducing when at least one of the states has a CIE. The finding, moreover, is robust: the interactive variable remains statistically significant and negative even after the introduction of competing economic variables, including trade interdependence and capital openness. These results are shown in table 2.3.12

Taken together, Hegre’s and Mousseau’s empirical work forces us to fundamentally rethink the liberal notions that increasing trade and joint democracy are, on their own, factors that necessarily lead to higher probabilities of peace. Yet we must return to the well-known point that quantitative findings, in and of themselves, are merely suggestive correlations; they cannot tell us anything directly about the causal mechanisms underlying the correlations. Conjectural interpretation is necessarily required. Our common scholarly goal must be this: to discover a plausible interpretation that covers as many of the findings as possible. In short, which of the causal explanations makes the most sense of all the diverse quantitative evidence?

TABLE 2.3 Mousseau’s Results on the Role of Democracy and a CIE

(Dependent Variable: Onset of a Fatal Militarized Interstate Dispute, 1961–2001)

Note: Mousseau 2009, 73. The subscript L indicates the choosing of the state in a dyad with the lower level of the particular variable (with subscript H the higher level). Standard errors for coefficients appear in parentheses (Mousseau does not report them for the control variables for reasons of space). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. CIE stands for contract- intensive economy. Models 1, 2, and 3 above correspond to Mousseau’s models 1, 2 and 6, respectively.

Hegre’s causal conjecture, borrowing from Rosecrance, is that higher development levels increase the costs of grabbing and holding territory, which might explain why higher trade only reduces the likelihood of militarized conflict when states are economically developed. This, however, can only be at best a partial explanation. Peter Liberman (1996a) has shown empirically that under a variety of conditions, even in the twentieth century, developed states can often effectively attack and then economically exploit other advanced economies. Mousseau’s argument points us in a different and potentially more fruitful direction. Developed economies are typically ones based on CIE structures that encourage higher levels of impersonal trust between strangers. Given this, their expectations regarding the future commercial environment are likely to be much more positive. In the language of this book’s theory, this implies that leaders in a CIE-rich environment will have much greater confidence that commercial partners will continue to have open access to raw materials, investments, and markets. Thus they will have more reason for optimism regarding their future power positions, and less reason for the initiation of preventive war or crises designed to coerce more raw material, investment, and market access at the point of a gun.

As I will now show, this interpretation is supported by a wide variety of other large-N tests conducted over the last decade, some of which directly employ the notion of commercial expectations to understand their results. Edward Mansfield, Jon Pevehouse, and David Bearce (1999–2000) demonstrate that preferential trading arrangements—a broad class of institutions that include free trade zones, common markets, and custom unions—have a statistically significant and negative effect on the likelihood of militarized interstate disputes. In a follow-up analysis, Mansfield and Pevehouse (2000, 788) show that the probability of a militarized interstate dispute is cut in half if the two states belong to a preferential trading arrangement than if they do not, and that these agreements have a conflict-dampening effect even when current trade is low or nonexistent. Drawing on trade expectations theory, these scholars offer a straightforward explanation for these findings: preferential trade arrangements “foster expectations of future economic gains” by reducing trade barriers while increasing the likelihood that participants will maintain minimal barriers off into the future. As such, they “enhance the credibility of commitments made by a state’s current administration to sustain open trade with selected trade partners” even as they help bind subsequent administrations that may be more protectionist in orientation (Mansfield, Pevehouse, and Bearce 1999–2000, 98).13 The commitment problem that makes trading states wonder about the other’s true willingness to maintain open trade into the future is therefore ameliorated, if not completely eliminated.

In subsequent work, Bearce (2001, 2003) backs up these conjectures through case studies. Examining three institutions that began life as regional trading arrangements—the Gulf Cooperation Council charter between Persian Gulf states, the Mercosur pact between states in the southern cone of South America, and the ECOWAS pact of West African states—he shows that expectations of future trade benefits helped to moderate incentives for militarized conflict.14 This proved to be true even when interstate trade levels were initially low, with positive expectations for the future giving states a stake in the present peace. Moreover, from Bearce’s perspective, it was not the mere existence of the regional pacts that helped foster better political relations. High-level meetings between state leaders and top officials were also critical to the establishment of greater degrees of trust regarding the others’ commitment to future trade and peace. In a large-N study that measures the degree of high-level meetings, Bearce and Sawa Omori (2005, 664, 671) go further. They show that high-level diplomatic contacts between states involved in preferential trade arrangements prove particularly important across a wide variety of model specification in dampening the likelihood of militarized conflict. Such contacts have a negative and statistically significant effect even in the presence of such alternative variables as the degree of economic integration and levels of trade interdependence. Bearce and Omori’s explanation is instructive. The more states engage in high-level contacts within a preferential trading arrangement, they suggest, the more state leaders can come to trust each other—with trust in their logic being defined as having “positive present expectations about the other actor’s future behavior.” As trust grows, actors come to believe that the other is indeed committed to maintaining their promises within the institutional structure.15

Commercial expectations also likely play a dominant role in the reality of any “capitalist peace” in world history. Such a peace has recently been asserted separately by Erik Gartzke and Patrick McDonald. Building on the idea that the democratic peace is more a reflection of economic structures than domestic institutions or liberal norms, Gartzke and McDonald seek to demonstrate that the statistical and substantive significance of joint democracy is either reduced or completely washed out once variables measuring degrees of joint capitalism are introduced. For Gartzke, capitalist states typically share higher levels of economic development, have common interests in maintaining valuable finance and trade flows, and are better able to signal their willingness to fight because the market repercussions associated with military conflict serve as costly signals of their resolve. These three elements together should make capitalist states less likely to become involved in a militarized interstate dispute.16 Table 2.4 reproduces some of Gartzke’s (2007, table 1, 177) key results.17 It illustrates that higher mutual financial openness, his primary measure of the level of market capitalism, has a negative and statistically significant effect on the likelihood of a militarized interstate dispute. Perhaps even more important, this variable’s addition to the baseline model has the effect of washing out the statistical significance of joint democracy. Gartzke thus concludes that any liberal peace is rooted not in the political institutions of democracy but instead in the economic openness that is associated with liberal democratic states.18

McDonald also puts forward an argument for a capitalist peace, but he comes at it from a different angle. He contends that when nations have high protectionist barriers to trade and the state itself owns a large percentage of key industries in the economy, leaders with aggressive intentions are less constrained from initiating military conflicts. With government coffers flush with tariff revenue and the profits from nationalized firms, and private businesses with foreign trade interests having less say in executive decisions, leaders are more able to initiate wars and expansionist policies when they so desire. Conversely, when trade barriers are low and government-owned firms constitute only a small part of the economy, leaders will be constrained from initiating conflicts both by the lack of financial resources and backlash from private business interests.

Table 2.4 Gartzke’s Results on the Role of Democracy and Capitalism (“Financial Openness”)

(Dependent Variable: Onset of a Militarized Interstate Dispute, 1950−92)

Note: Gartzke 2007, 177. The subscript L indicates the choosing of the state in a dyad with the lower level of the particular variable (with subscript H denoting the higher level). Continguity, major power, and alliance are dummy variables, while distance and capability ratio are logged variables. I have omitted Gartzke’s controls for region to save space. Standard errors for coefficients appear in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Models 1, 2, 3, and 4 correspond to Gartzke’s models 1, 2, 4, and 5, respectively.

McDonald’s empirical work seems to support these domestic-level explanations. His measures of protectionism and government ownership of the economy are both statistically significant as well as in the expected positive direction. That is, as protectionism and government ownership grow, there is a greater likelihood of a militarized interstate dispute. When no interactive terms are used, as depicted in table 2.5, trade dependence has no statistical significance. Something interesting happens, however, when McDonald introduces an interactive term, dependence × protectionism, to capture the possibility that trade’s effect is conditional on the level of tariff barriers. The interactive term is positive and statistically significant (as is the protectionist variable on its own), while the coefficient on dependence is negative and now shows statistical significance. These results, as McDonald (2009, tables 4.4 and 4.5, 102–5) presents them (i.e., without the control variables), are displayed in table 2.6.19

How do we interpret these findings? One implication, as McDonald (ibid., 104–6) notes, is that higher bilateral trade flows may only inhibit military conflict when both states have relatively low levels of import barriers. But the findings also indicate that even “when bilateral trade is absent between two members of a dyad, higher levels of regulatory barriers still increase the likelihood of military conflict.” Both of these empirical insights fit perfectly with the trade expectations argument. High protectionist barriers will propel states that are already dependent on trade toward the initiation of militarized policies or even war, knowing that such actions can help to reestablish access to vital resources, investments, and markets, thereby avoiding decline. We will see this logic unfold with a vengeance in the Japan 1941 case (chapter 5). Even when current trade is low or nonexistent, though, highly protectionist stances by state X can provoke militarized behavior by state Y if Y needs what X’s sphere can offer, but believes that there is little possibility of gaining access to that sphere. This, as chapter 6 discusses, was a major causal reason for ongoing Cold War tensions between the United States and Soviet Union after 1944 up to the late 1980s.

Interestingly, McDonald’s domestic-level argument has a difficult time explaining the second part of these findings. To be sure, when trade is high, large import barriers could well provide the revenue that is supposed to facilitate the aggressive policies of illiberal leaders according to McDonald’s logic. Yet when trade is low or nonexistent, trade barriers such as tariffs generate little or no revenue for the simple reason that trade is not flowing between the two states. By focusing only on the removal of constraining factors such as low government revenue while offering no propelling rationales for state aggression, McDonald’s theory cannot explain why states that have little or no current trade might still be pushed into conflict for economic reasons. If they have a strong unfulfilled need for trade, however, and each believes that the other is not likely to satisfy this need, then conflict, according to trade expectations theory, is likely. In short, a trade expectations approach can provide a parsimonious explanation for the impact of protectionism on militarized conflict that covers both dimensions of McDonald’s empirical findings, including the one left unexplained by his domestic-level argument.20

Table 2.5 McDonald’s Results on the Role of Protectionism and Government Ownership (“Public”)

(Dependent Variable: Onset of a Militarized Interstate Dispute, 1970−2001)

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Economic and domestic variables |

|

|

ProtectH (tariff levels) |

0.024*** |

0.020*** |

|

(0.007) |

(0.007) |

PublicH (government ownership) |

— |

0.014*** |

|

|

(0.004) |

DemocracyL |

−0.046*** |

−0.036** |

|

(0.013) |

(0.013) |

DependenceL |

−2.691 |

−3.415 |

|

(5.442) |

(5.158) |

Control variables |

|

|

Power preponderance |

−0.116* |

−0.112* |

|

(0.061) |

(0.060) |

Great power |

1.408*** |

1.445*** |

|

(0.210) |

(0.203) |

Interests |

−1.074** |

−0.998** |

|

(0.359) |

(0.352) |

Allies |

0.657** |

0.684** |

|

(0.205) |

(0.207) |

Distance |

−0.298*** |

−0.279*** |

|

(0.091) |

(0.094) |

Contiguous |

2.187*** |

2.211*** |

|

(0.282) |

(0.286) |

DevelopmentL |

1.9 × 10−4*** |

1.7 × 10−4*** |

|

(7.1 × 10−5) |

(7.0 × 10−5) |

Development2L |

1.2 × 10−8 |

** 1.2 × 10−8** |

|

(5.1 × 10−9) |

(4.9 × 10−9) |

Number of observations |

87,708 |

85,416 |

Note: McDonald 2009, 102. The subscript L indicates the choosing of the state in a dyad with the lower level of the particular variable (with subscript H denoting the higher level). Standard errors for coefficients appear in parentheses. *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. Models 1 and 2 above correspond to McDonald’s columns 1 and 3, respectively (his columns 2 and 4 provide an alternative specification of the protect variable). McDonald notes that splines were added to all models, but not shown.

Table 2.6 McDonald’s Results on the Interaction of Dependence and Protectionism

(Dependent Variable: Onset of a Militarized Interstate Dispute, 1970−2001)

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

ProtectH (tariff levels) |

0.019.** |

0.015* |

|

(0.008) |

(0.008) |

PublicH (government ownership) |

— |

0.014*** |

|

|

(0.004) |

DependenceL |

−24.483* |

−24.410* |

|

(14.210) |

(13.353) |

DependenceL × protectH |

3.737** |

3.615* |

|

(1.898) |

(1.850) |

Number of observations |

87,708 |

85,416 |

Note: McDonald 2009, 105. In his published version, McDonald does not include his control variables to save space (for the list, see my table 2.5). The subscript L indicates the choosing of the state in a dyad with the lower level of the particular variable (with subscript H denoting the higher level). Standard errors for coefficients appear in parentheses. *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. Models 1 and 2 above correspond to McDonald’s columns 1 and 3, respectively (his columns 2 and 4 provide an alternative specification of the protect variable). McDonald notes that splines were added to all models, but not shown.

McDonald’s other main large-N finding—that higher levels of government ownership in the economy are associated with increased risks of militarized conflict—is more directly consistent with his domestic logic. States in which the government runs much of the economy through state-owned enterprises are indeed more likely to have the revenue needed to prepare for and initiate war. Yet McDonald still has no explanation for why such states might be peaceful for many years before they decide to initiate war or dangerous crises. His case studies do not help him here, Number of observations given that he provides no examples of a state with high government ownership initiating a militarized crisis or war.21 As we will see in the remaining chapters, there is little evidence that leaders of great powers in the two centuries after 1790 saw strong government control over public enterprises as even a necessary condition for the initiation of conflict, let alone a sufficient one. When there was the rational need for conflict, great powers of all stripes proved more than willing and able to initiate hard-line policies, even when government ownership of the economy was minimal—as it was with such states as Britain and the United States, for instance. The remaining chapters show that great powers typically started conflicts only when they saw looming threats to their future access to raw materials, investments, and markets.22 In essence, it is declining confidence in the future commercial environment, not domestic economic structures, that best explains why states so often fall into war and militarized crises.

QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS: A NEW APPROACH AND A SUMMARY OF THE FINDINGS

The above look at recent quantitative work has shown how an expectational approach not only can supply a powerful explanation for many of the large-N results over the last decade but also explain anomalies that remain in the quantitative findings. Yet large-N analysis, even if it is the dominant methodology for testing claims about interdependence and conflict, is clearly not enough. As I discuss below, the approach has a number of important limitations inherent to its very setup, including its inability to directly measure leader expectations of the future and its difficulty in dealing with the specific causal roles played by different variables within situations of complex causality. In particular, quantitative approaches have a problem in dealing with rare events of a certain kind—namely, those phenomena such as war and crisis initiation where leaders, prior to such events, are aware of their own impact on the very factors that go into the mix of variables determining the rare event.

Still, the problems that may be inherent in large-N analysis do not imply that case study research, at least as it has been traditionally practiced, is necessarily a superior methodology. This research has generally suffered from two overlapping concerns: selection bias and a lack of generalizability. Qualitative research has always had one obvious advantage over large-N work: it can reveal the causal mechanisms that join independent variables to dependent ones, thereby helping explain why factor A or factor B is associated with event E (George and Bennett 2005). This goes beyond the inherently correlational analysis of quantitative methods. Yet it also leads qualitative researchers to select cases that are particularly useful in illustrating the way these causal mechanisms work in practice. Through in-depth process tracing, qualitative scholars can show to what extent the leaders acted for the reasons posed by one theory versus another, and how salient these reasons were in the context of all the factors shaping and constraining the actors at the time. But because the goal of traditional qualitative research has been to reveal why actors did indeed act, researchers tend to fall into the trap of picking cases that do a good job illustrating causal mechanisms while ignoring cases that do not fit the model. Even when such researchers can plausibly demonstrate that the cases chosen are “hard cases” for the theory being tested, or that they conform to the dictates of such techniques as John Stuart Mill’s methods of difference or agreement, there is still the problem of generalizability. We might have confidence for the cases selected, but we have no way of knowing how well the theory works or under what conditions for the broader population of cases.23

These related problems of selection bias and generalizability might seem inherent to qualitative case study research. As we will see, however, when dealing with rare events, it is possible, at least as an ideal, to lay out what is essentially the “universe” of cases within a particular time frame and for a certain type of actors (e.g., great powers). Setting forward this universe of cases forces a researcher to determine how well the theory or theories being tested do across the full scope of cases. In-depth analysis will still be required on cases that have the potential to support a scholar’s favored theory—after all, the scholar must still convince the reader that the theory does indeed explain particular cases. Yet by framing the cases that work within the larger context, we avoid the selection bias charge while also providing a sense of how well the theory travels across space as well as time. And most important, from a practical standpoint this approach tells us what we want to know: how often any specific theory explains the rare events of interest and how frequently it does not. This allows us to transcend stale debates about whether particular theories or factors “matter” to concentrate on more relevant questions: how often they matter, and with what relative force or salience.

A NEW APPROACH TO THE QUALITATIVE STUDY OF RARE EVENTS IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

Rare events in international relations such as the onset of crises and wars pose significant challenges for large-N researchers. The fact that there are so few positive cases of the phenomenon to be explained can play havoc with measures of coefficients and statistical significance. These methodological concerns can be mitigated to some degree by incorporating all the rare events but only a small randomized percentage of the cases of nonevents into the sample.24 From a qualitative researcher’s perspective, however, such large-N research is missing a key point: that rare events are rare for a reason. Rare events in international relations are typically situations where a complex set of factors must come together for the event to occur. Each of the particular factors is a necessary condition for the event, since without each factor the event would not happen. Yet when put together, they become sufficient to produce the event. This is the deductive logic of “individually necessary, jointly sufficient” (INJS), whereby factors A, B, and C must be included in a particular bundle of causal variables before event E can come about. And for almost all phenomena in international relations, there are multiple pathways to a specific type of event such as war or alliance formation. This means that other complex bundles of factors—perhaps A, D, and J, or D, K, L, and M—may also be sufficient for E to arise.25

Such complex conjunctural causality poses a problem for large-N research, given that regression analysis is designed to show the independent and additive impact of individual causal variables, not how factors might have to come together as necessary conditions before phenomenon E will occur. As we saw earlier, quantitative researchers can deal with complex conjunctural causality to some degree through the use of interactive variables, with a new variable A × B included in the regression model instead of A and B being treated only separately and additively (Friedrich 1982; Braumoeller 2004). There is a limit to this solution, though. If factor A operates within a causal bundle only as a threshold condition—having to reach a certain level before it has any important causal effect, but then having little or no additional effect after that threshold is achieved—then treating A as a part of multiplicative interactive variable will create significant distortions in the results. If we as researchers do not know this threshold level ahead of time, or if leaders themselves have different estimates of the threshold level, then large-N tests will frequently see no statistical significance for interactive variables despite the fact that A and B together are indeed crucial parts of the causal story. To take an obvious example, if leaders in state Y believe they need a certain level of domestic popularity—say, at least a 50 percent positive approval rating from the public—before they can contemplate launching a successful war against state X, then this threshold will operate as a necessary condition for war. Anything below 50 percent and the leaders will have to hold off from starting the conflict. But ratings above 50 percent may have no additional impact on the leaders’ predisposition to start a war, meaning that including domestic popularity as factor A in an interactive variable may lead to a statistically insignificant result for something that is in fact critical to the overall “mix” that the leader is considering. This would be especially true if leaders in states W and Z had different estimates for the domestic support threshold.26

There are additional problems, however, that quantitativists face in dealing with the complex conjunctural causality that is inherent to rare events in international relations. For one thing, while quantitative research can show that a factor is correlated with the emergence of a crisis or war, and can use interactive variables to capture some aspects of complex causality, it cannot say what causal role a particular factor played within any complex INJS pathway leading to E or not E. As scholars and as leaders, we need to know more than simply that factor A was associated with the arising of event E. We need to know whether factor A was propelling actors toward behaviors that led to E, or whether it played more of a facilitating or reinforcing role for other more primary propelling variables, or indeed whether it was constraining the actor from taking actions that might have otherwise produced E.

These are terms that are frequently thrown around in academic discourse but rarely defined. A propelling factor is one that directly involves an actor’s ultimate ends and desires or fears—its “reasons” for acting. A leader worried about the state’s future power because of a trade cutoff, for example, is propelled by the fear of the future and a concern for security into initiating a crisis or war. A facilitating factor is one that is incidental to the actor’s ends, but needs to be in place before the desired action can be carried out. The above-mentioned need of leaders to reach a threshold of domestic support before starting a war is an obvious instance of a facilitating factor: this support is not pushing the leader into war but instead must be achieved before the war can begin. A constraining factor is in some sense the flip side of a facilitating factor: if the public support is not there, then the leader is constrained from acting. More narrowly, though, a constraining factor is something that is pulling actors back from doing what they might otherwise want to do. We saw this with the liberal argument for why trade leads to peace—namely, that trade constrains leaders who might have unit-level reasons for wanting war by increasing the value of continued peace. A reinforcing factor is one that operates to make the potential effect of a key propelling factor that much more likely to occur. Take, for example, ethnic or ideological differences between dependent nation Y and the nation cutting it off from trade. Such differences might easily create an even greater desire for war, since Y has a stronger reason to fear the implications of the relative decline caused by the cutoff.27

When we are dealing with the complex conjunctural causality underpinning rare events, understanding the functional role played by a variable is critical. If we know that when A, B, and C come together, event E typically follows, it is important to know whether factor A was propelling state Y to war or simply facilitating the decision for war. Indeed, the very “support” or lack of support for a theory depends on it. In this book, for example, if a leader’s level of domestic popularity (or lack thereof) is actually propelling the actor to start a war, and the trade environment is acting as merely a constraining or facilitating factor, then liberal and neo-Marxist arguments for war are supported. Conversely, if the trade environment is actually propelling the leader to choose war to maximize the nation’s security, and domestic popularity is simply a constraining or facilitating factor, then economic realist and trade expectations arguments have potential explanatory force. Note that large-N quantitative work cannot help us here: in either scenario, all the factors are correlated with war, and thus all the theories seem equally plausible as explanations.

Another dimension that complicates large-N work on rare events in international relations is the specific nature of the endogeneity problem. Events such as crisis initiation and war are almost always a function of the decisions of a select few individuals at the heads of states X and Y. Such leaders are usually highly aware that they hold the fate of their nations in their hands, and that many of the conditions that can increase the likelihood of crisis and war depend on their “choices,” and therefore are a function of their own diplomatic and military behavior. Military and trade-security dilemmas of the kind discussed in the previous chapters are only two examples of the endogeneity concerns that leaders may be cognizant of. Quantitative methodologies have an inherent difficulty dealing with such concerns, since it is the leaders’ anticipations of future effects that is affecting their behavior now. Large-N data sets, at least in international relations, can only develop rough proxies for leaders’ anticipations of effects; there are, after all, no across-the-board historical surveys of leaders that can measure such beliefs. Documentary process tracing, on the other hand, does give a researcher at least some access to the inner thinking and planning of leaders as they grapple with their awareness of feedback loops and endogeneity. Moreover, in a book such as this one where expectations of the future are a fundamental variable said to be driving behavior, the best way to investigate leader expectations is ultimately through careful documentary analysis. Quantitative work of the kind studied in the first half of this chapter can allow us to infer that expectations of the future were at work across many cases, but such inferences will be indirect and thus ultimately unsatisfying. We need to go further, and that is where qualitative historical work shows its stuff.

This discussion of endogeneity and leader anticipations of the future leads to an additional point. In situations such as great power politics where a few key leaders have great influence over the destinies of nations, decision makers know that they have the ability to manipulate both the other’s beliefs and the characteristics of their social unit—in this case, the nation-state. This means that hard-line actions such as the initiation of war can be deferred until certain domestic or international conditions have been altered to facilitate a policy shift. These two facts play havoc with large-N analyses, since they create the possibility not only of feedback loops but also of leaders deliberately shaping key parameters before embarking on important actions that bring on rare events. As a result, the posited control variables in a large-N analysis will often not be independent of one another. Indeed, they will likely move together in a predictable direction just before the rare event arises. A war that is planned in advance, for instance, will likely see the build up of military power, tightening of alliances, mobilization of nationalism and domestic support, reduction of democratic rights, and development of offensive technologies just before the war is initiated. Any correlation of these variables with the dependent variable will be overstated by the fact of prewar planning, with the real propelling cause of both war and changes in these variables likely overlooked.28

For all these reasons, qualitative documentary analysis is the best method for studying rare events in international relations, at least when one has access to the documents that reveal the inner decision-making process of the actors in question. In-depth documentary work provides us with a window into the thinking of key decision makers as they make estimates of future realities, grapple with trade-offs associated with feedback loops and escalatory spirals, and adjust their behavior to alter the factors that will serve their ends. Yet the way qualitative case study analysis has been traditionally approached in international relations leaves much to be desired, precisely because researchers are prone to pick only a handful of examples from the larger population of cases. This leads to the above-mentioned charges of selection bias and lack of generalizability—charges that always seem to hamstring qualitative researchers when they try to show the value of their craft relative to quantitative methods.

Yet when dealing with rare events, these two concerns are easily overcome, at least in theory, by one simple move: the consideration, across a defined period, of as many of the rare events in question for which one can get adequate information.29 For practical reasons—including a researcher’s time and the availability of documents—boundaries for research have to be established. One might examine, say, all the initial formations of great power alliances since 1870 or all the onsets of civil war since 1918. Decisions on boundaries should also be guided by methodological considerations, including the type of actor being studied and whether the overall time frame can be said to favor or not favor the theories being tested. In this book, I look at the onset of essentially all the significant great power crises and wars from 1790 to 1991. The choice to focus on great powers is not just a practical one (i.e., the bounding of the number of rare events and the emphasizing of cases where documents are generally available). It is also a theoretical one, given that all the theories before us are ones that assume anarchy. Conflicts between smaller regional powers might be explained by such theories. Yet the fact that these powers can be shaped and constrained in their behavior by the overhanging influence of great powers makes the tests less reliable (Copeland 2012a).30

The time frame of 1790 to 1991 was chosen not just because of the availability of documents. The period is also one that is quite favorable to liberal theories that have dominated the study of interdependence and war, and generally less favorable for economic realist and trade expectations approaches. If I were to concentrate on the era from 1550 to 1750, for example, a critic could easily charge that economic realism and trade expectations theory are much more likely to work with regard to the heyday of great power mercantilism. During this time, leaders thought more in zero-sum terms, and did not yet have access to the liberal economic theories of Smith, Ricardo, and modern trade theory.31 From 1790 to 1991, in contrast, we should expect that liberal theories will do well, with leaders thinking increasingly in terms of the constraining effects of absolute gains from trade and less in terms of the outmoded arguments of early mercantilism. If liberalism does not do well during this modern period, and economic realism and trade expectations theory are supported, then there will be greater confidence that the latter theories have withstood a “hard period” for the upholding of their claims.

This approach of focusing on all the rare events within a certain time frame and for a certain type of actor may still seem to suffer from the bias of “selecting on the dependent variable”—that is, choosing cases based on the fact that event E occurred.32 There is a simple way to mitigate this concern. In addition to examining the immediate outbreak of a crisis or war, we can look at the periods leading up to the crises and wars of interest, to see if the planning for conflict, levels of tension, and probabilities of war changed as the core independent variables changed.33 Of course, because crises and wars are a function of complex bundles of factors, and because leaders will seek to manipulate these factors to facilitate the initiation of conflict under optimal circumstances, we cannot expect changes in individual independent variables to drive changes in conflict levels. Even if such variables are propelling factors, they are nested within sets of necessary facilitating factors that must be in place before leaders would be rational to start a crisis or war. Qualitative research thus needs to be subtle, looking at how the core independent variables specified by the main theories interacted with other supporting factors to either keep the peace or bring on conflict.

The above approach to rare event research has important implications for the way scholars orient themselves to the study of “evidence.” It is a self-evident point that rare events in international relations and comparative politics, such as crises, revolutions, and wars, will be a function not of a single complex bundle of INJS conditions but rather different bundles of factors operating with different causal force at different places and times. That is, even when we think in terms of complex conjunctural causality, we must still think in terms of multiple pathways to event E. Recognizing this starting point requires a critical shift in research focus. We must give up any search for a single “master explanation” for rare event E across time and space. Instead, we must look at the competing theories in terms of the competing bundles of variables said to drive E. Then we can look to see how often it is the case that a bundle from one theory will do a better job explaining the arising of E than a bundle from a competing theory.

Yet we must also move beyond stale debates in both quantitative and qualitative research where scholars seek to show that a factor or set of factors “matters” within a larger causal picture—in quantitative work, the demonstrating of statistical and substantive “significance” relative to established control variables; in case study research, the showing of a factor’s importance in select cases. Given that almost every factor identified in political science can be said to sometimes matter, any useful research agenda must revolve around the issue of how frequently a factor plays a critical causal role (propelling, reinforcing, etc.) within the complex causality that is producing event E.

More specifically, in this book I am interested in answering three key questions. How often is it the case that variables related to economic interdependence were important to the onset of crisis and war across the 1790 to 1991 period? If interdependence is indeed causally important, how frequently is it the case that the variables and causal logic of trade expectations theory do a better job explaining the onset of conflict than the variables and logic embedded within liberal arguments and economic realism? And given that factors having nothing to do with interdependence may be also at work in specific cases, what is the relative salience of a theory’s mechanisms compared to the factors posed by competing noncommercial theories? By covering the essential universe of cases during the specified time frame and scrutinizing the cases using documentary analysis, we can get a good handle on each of these three questions. As I summarize in the next section, economic interdependence not only plays a far more significant role in modern great power conflicts than has been previously appreciated but within those cases where interdependence is key, trade expectations theory and economic realism also do a solid job in explaining the vast majority of the cases.34

This section provides a broad overview of the results of the in-depth historical documentary work that is detailed in chapters 3–8. It serves two main purposes. First, it provides the reader with a handy reference tool for remembering the key findings of each of the forty case studies. Second, it offers a summary that can be dissected according to the guidelines for rare event qualitative research outlined above. We can determine, at least as a first cut at a broad swath of history, not only how important economic interdependence is to the ups and downs of great power conflict but also the role and salience of the trade expectations logic versus its competitors. Moreover, because the historical chapters cover essentially all the great power cases of crisis and war between 1790 and 1991—including ones having little to do with economic interdependence, the forty cases give us direct insight into the relative significance of systemic versus domestic-level factors for international politics at the highest level.

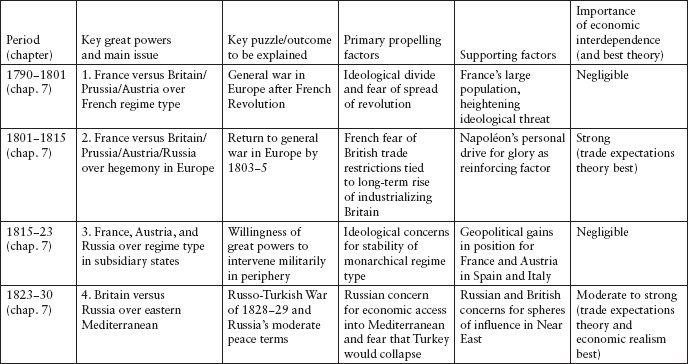

Table 2.7 lays out the results from these forty case studies. Each case can really be thought of as a “case period,” since I investigate the years and months leading up to a major event in great power relations (a crisis, a war, or in the case of US-Soviet relations, the ending of the Cold War) as well as the event itself. The first two columns of table 2.7 provide details on each case period in terms of the years investigated, great powers involved, and main issue being considered. A clear dividing line between case periods can, of course, be hard to establish. Three criteria were used to mark out the case periods. For one, the period had to be marked by a particularly salient issue or important event. Thus the wars from 1790 to 1815 are separated into two case periods, the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars, given that the battles of the first were directly related to the fall out of the French Revolution while those of the second were driven by the hegemonic calculations of a single French leader. This criteria alone, however, is not sufficient, considering that conflicts can revolve around a single large issue for decades, such as the British and Russian concerns for dominance in the eastern Mediterranean from 1820 to 1880. If a turn to a new dramatic event involves new great powers or has a distinctly different geographic focus, I treat this turn as a distinct case period. The period 1943–45, for example, is broken into two case periods: one for the US-Soviet dispute in 1943–44 over the control of Iranian oil and another for the US-Soviet struggle over the postwar European order in 1943–45. The first of these is of interest because of its distinct regional character. The second not only has a different regional focus but also ended up leading to the larger Cold War conflict that dominated the next four decades of great power history.35

A final criterion—the relative degree of independence of events—was used to ensure that the years of struggle between two or more great powers were not divided up too finely. It would make little sense, for instance, to treat the series of great power wars from 1803 to 1815 as “separate” case periods, since they were all shaped by one overarching factor: the hegemonic aspirations of Napoleonic France. Treating them as independent events would create a bias in favor of whichever theory does a good job for the 1803–15 period as a whole (giving it more “hits” than it deserves). The same is true for periods of peace that may involve multiple crises or disputes all tied to one larger geopolitical question or issue. From 1905 to 1914, for example, the Germans and their Austrian allies were involved in a series of crises over great power control of Morocco and the Balkans region. These crises, and whether they escalated or not, were all bound up in the larger issue of the German-Austrian alliance’s future position within the global economic and strategic system, as I show below and elsewhere (Copeland 2000b, chapters 3 and 4). Treating these individual crises as independent cases would again distort the results in favor of the theory that does the best job explaining World War I.36

The results in table 2.7 are designed to be self-explanatory, so I won’t go through them in any detail. Columns one and two describe each case period in terms of the key great powers in the struggle and the main issue animating the time period. The third column outlines the main historical outcome or puzzle for each case period that requires explanation, such as the outbreak of war between Japan and Russia in 1904, or why the Soviet Union sparked a crisis over Berlin in 1948. The fourth and fifth columns lay out the primary factors that went into the complex mix of variables that led to the main outcome for each case period. Column four is the crucial one here. It summarizes the findings on the primary propelling factor or factors that drove the great powers into conflict, or in the case of 1963–74 and 1984–91, helped them achieve a dramatic lessening of tensions.37 Column five depicts some of the supporting factors that served as reinforcing, facilitating, or constraining variables within the larger causal mix.

The sixth and final column provides the short answers to the first two of the three questions posed above. It tells us whether commercial variables were important in the case (question one), and if so, which of the main theories does the best job of explaining the causal role of these variables (question two). By assessing the significance of trade and finance within the case period on a scale from “negligible” to “moderate” to “strong,” this column, when read in conjunction with columns four and five, also indicates the relative salience of the commercial variables within the overall mix of factors driving the events (question three).

Table 2.7 thus offers the reader not only a quick overview of the findings of the chapters to follow but also a means of assessing how often economic interdependence matters and how frequently each of our main theories can explain the case periods at hand. As is to be expected in situations of complex causality with multiple pathways, there are many case periods that have little or nothing to do with economic interdependence per se. In ten of the forty cases, I found no real documentary evidence that interstate trade or financial variables drove the events of the case period. In such situations, none of the variables of our main theories had causal salience relative to noncommercial factors.38 Yet what is surprising, at least for traditional international relations scholars who tend to downplay the importance of commercial variables, is just how often interdependence was indeed important.39 In thirty of the forty case periods, or 75 percent, economic interdependence played a moderate to strong causal role in shaping the events. This does not mean, of course, that commercial variables were the only factors driving the events, and columns four and five give a sense of some of the other propelling, reinforcing, and facilitating factors at work within the cases. Still, the fact that interdependence had salience in three out of four case periods is prima facie evidence that the economic dimension of great power politics cannot be ignored.

Turning to the cases where economic interdependence was important, we see that trade expectations theory does well in head-to-head tests with its competitors. Trade expectations theory finds support in twenty-six of the thirty cases (86.7 percent), while economic realism is supported in eleven of thirty cases (36.7 percent) and liberalism in three of thirty cases (10 percent).40 What is most surprising about these results is just how poorly commercial liberalism performed across the two centuries considered.41 Even for the three cases in which liberalism was supported—Russia’s moderation in the 1839–40 eastern crisis, Bismarck’s decision to turn to imperialism in 1883–84, and Japan’s restraint over Manchuria in the late 1920s—it did not cover the case period on its own but instead worked only in conjunction with trade expectations theory, with each explaining differing aspects of the events. And for what should have been “most likely” cases of unit-level factors being unleashed as trade falls—German and Japanese behavior up to World War II, the Berlin Crisis of 1948, and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950—liberal arguments could not explain the driving forces for conflict.

Trade expectations theory and economic realism sometimes worked together within specific cases, such as the Venezuelan Crisis of 1895–96, with trade expectations theory explaining the behavior of one great power and economic realism the behavior of the other.42 Economic realism did well on its own for three important case periods: France’s behavior in the eastern Mediterranean in 1830–40, the Japanese war with China in 1894–95, and Japan’s moves against China and Russian Siberia from 1914 to 1922. Trade expectations theory, however, proves significantly stronger than economic realism across the broad sweep of case periods. It provides a strong explanation on its own for fourteen of the thirty cases involving economic interdependence, and its logic is at least as salient as economic realism for the nine cases where both trade expectations theory and economic realism help explain the events of the case period.

Needless to say, readers may disagree with the exact way that I characterize the case periods along with the propelling forces driving great power behavior. The proof is in the pudding, and it will be up to me to demonstrate in the following six chapters (and my follow-up volume on commerce and US foreign policy) that the documentary evidence justifies my understanding of each of the case periods. Within the context of the methodological setup outlined above, though, dissenting opinion is not a problem but instead a healthy and indeed necessary part of a research program’s long-term intellectual progress. It is only through back-and-forth discussion that the international relations field can reach relative consensus on the cases in this book, or on cases that are added from other time periods. And it is only through increasing consensus that we can say that there has been an “accumulation of knowledge” in international relations.

The case studies that follow, therefore, are first steps in an extended process and are meant to provoke scholars into debates that will hopefully achieve this long-term accumulation of knowledge. They are not designed to provide definitive interpretations of the case periods—an impossible task given the amount of documentary evidence available for the complex events discussed herein. This being said, I am still confident that readers will find the historical chapters not simply provocative but also plausible and even convincing. For each case period, I set my arguments against the main historical interpretations of diplomatic history, including both economic and noneconomic contentions. When the evidence suggests that economic interdependence had little causal role in the case period, I cover the events in short order, summarizing the key factors to ensure a broad picture of the overall salience of systemic versus unit-level variables across the forty cases. Yet when interdependence is important, I slow down to examine in depth the documentary evidence for the competing theories of interdependence and war. In this way, we can see not only the extent to which these theories explain the particular case periods but also the way their factors work with noncommercial variables to bring about the results. This allows us to reject or support certain key noneconomic interpretations of history put forward by diplomatic historians and political scientists as I focus on the competing economically based logics from chapter 1.

In the end, the diplomatic historical work of chapters 3–8 reveals the overriding importance of systemic variables and security fears in the ebb and flows of world history. Liberalism’s view that unit-level forces that favor conflict get unleashed when trade falls is rarely upheld. The great powers in these cases were almost always driven primarily by their fears of the future and the implications of external changes for their long-term security. Even in case periods where economic interdependence had no causal role to play, unit-level variables operated more as external factors that heightened leaders’ senses of national insecurity than as direct propelling forces “from within.”43 Ideological differences between monarchy and republicanism, for example, played critical roles in the 1790–99 and 1815–22 periods, but largely because they caused insecure leaders to worry about the future stability of their states.44 To be sure, in a number of the cases unit-level drives for status (“glory”) and wealth (“greed”) were important supporting factors in the outbreak of conflict. And who would want to deny that the personal motives of Napoléon, Bismarck, or Hitler played a role in leading such individuals to bring war down on their neighbors? Yet as the historical chapters suggest, such unit-level factors operated largely as reinforcing factors to the more salient external forces that propelled these actors and their supporters into conflict.45

I will close this chapter with the self-evident observation that my interpretations of the cases of chapters 3–8 are unquestionably shaped by my own theoretical framework. There is no escaping the impact that theoretical frameworks have on the filtering of one’s view of reality—not for this scholar, not for any scholar. The only thing one can do, therefore, is to seek to be as self-conscious as possible about such potential biases, and minimize distortions through the objective handling of documentary evidence and a careful methodological setup. By examining the universe of great power cases for a hard period (1790–1991), for example, this book was forced to deal with cases that do not work well for trade expectations theory. Moreover, I deliberately included potentially marginal cases such the Belgium Crisis of 1830–31 as well as the French and Austrian interventions of 1815–22 in order preempt charges of historical bias.46 Yet the evidence from the following chapters nonetheless shows the surprising power of the trade expectations logic across a wide variety of settings and time periods. Notwithstanding my efforts to address counter-arguments, my assertions for such controversial cases as US-Japan 1938–41 and the origins of the Cold War may still strike some readers as too one-sided. My hope, however, is that by the end of the book, even skeptics will not be able to return to well-known historical cases without a new appreciation of the role of trade expectations on the course of world history. And if such skeptics jump into the fray to adjust the interpretations in a way that builds a new consensus for each case period, or indeed to bring in new case periods to widen the historical scope, then a true accumulation of knowledge within the international relations field may yet be in sight.

_____________

1 Notable examples of those who do examine cross-case historical evidence include Ripsman and Blanchard 1995–96; Gholz and Press 2001, 2010; Papayoanou 1996, 1999; Bearce 2001, 2003; McDonald 2009.

2 Early studies include Polachek 1980, 1992; Polachek and McDonald 1992; Gasiorowski and Polachek 1982; Gasiorowski 1986.

3 Oneal and Russett 1997, 1999, 2001; Oneal, Oneal, Maoz, and Russett 1996; Oneal, Russett, and Davis 1998.

4 Barbieri 1996, 2002.

5 See, for example, the debate in the special issue of the Journal of Peace Research 36, no. 4 (1999).