A verb shows the performance or occurrence of an action or the existence of a condition or a state of being, such as an emotion. A verb is the most essential part of speech—the only one that can express a full thought by itself (with the subject understood) {Run!} {Enjoy!} {Think!}. (One-word sentences such as Why? or Yes alone can express complete thoughts, but these are in fact elliptical sentences omitting a clause implied by context. {Why [did she do that]?} {Yes[, you may borrow that book].}. See § 313.)

Verbs act. Verbs move. Verbs do. Verbs strike, soothe, grin, cry, exasperate, decline, fly, hurt, and heal. Verbs make writing go, and they matter more to our language than any other part of speech.

—Donald Hall

Writing Well

138 Transitive and intransitive verbs.

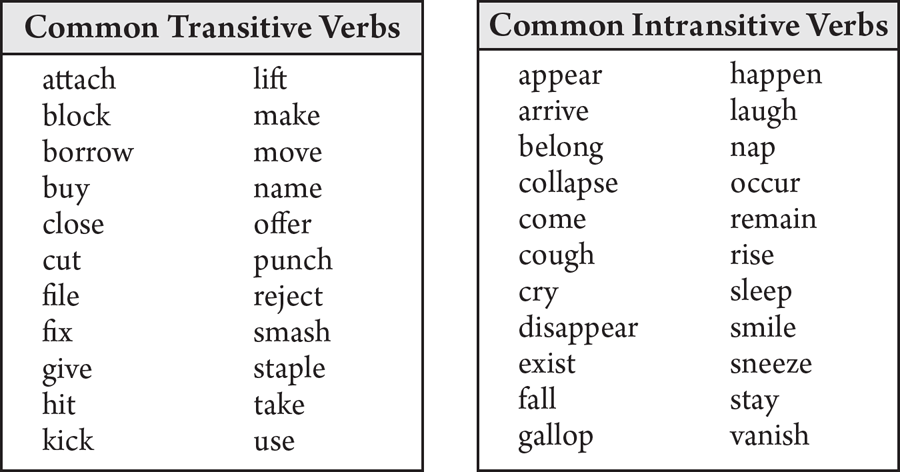

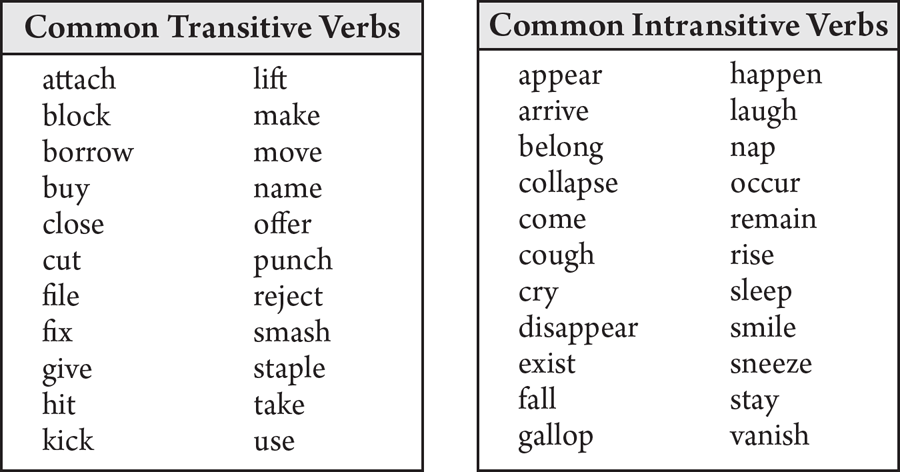

Depending on the presence or absence of an object, a verb is classified as transitive or intransitive. A transitive verb requires an object to express a complete thought; the verb indicates what action the subject exerts on the object. For example, the cyclist hit a curb states what the subject cyclist did to the object curb. (A few transitive verbs have what are called cognate objects, which are closely related etymologically to the verb {drink a drink} {build a building} {see the sights}.) An intransitive verb does not require an object to express a complete thought {the rescuer jumped}, although it may be followed by a prepositional phrase serving an adverbial function {the rescuer jumped to the ground}. Many verbs may be either transitive or intransitive, the different usages often distinguishing their meanings. For example, when used transitively, as in the king’s heir will succeed him, the verb succeed means “to follow and take the place of”; when used intransitively, as in the chemist will succeed in identifying the toxin, it means “to accomplish a task.” With some verbs, no such distinction is possible. For example, in I will walk; you ride, the verb ride is intransitive. In I will walk; you ride your bike, the verb ride is transitive, but its meaning is unchanged. A verb that is normally used transitively may sometimes be used intransitively to emphasize the verb and leave the object undefined or unknown {the patient eats poorly [how well the patient eats is more important than what the patient eats]}. The test for whether a given verb is transitive is to try it with various possible objects. For each sentence in which an object is plausible, the verb is being used transitively. If an object doesn’t work idiomatically, the verb is being used intransitively.

Some verbs, called ergative or ambitransitive verbs, can be used transitively or intransitively {the impact shattered the windshield} {the windshield shattered}. The noun that serves as the object when the verb’s use is transitive becomes the subject when the verb’s use is intransitive. For example, with the noun door and the verb open, one can say I opened the door (transitive) or the door opened (intransitive). Many verbs can undergo ergative shifts {the torpedo sank the boat} {the boat sank}. For example, the verb ship was once exclusively transitive {the company shipped the books on January 16}, but in commercial usage it is now often intransitive {the books shipped on January 16}. Likewise, grow (generally an intransitive verb) was transitive only in horticultural contexts {the family grew several types of crops}, but commercial usage now makes it transitive in many other contexts {how to grow your business}. Careful writers and editors employ such usages cautiously if at all, preferring well-established idioms.

140 Dynamic and stative verbs.

Verbs can be classified as either dynamic (or action) or stative (or nonaction). Dynamic verbs express actions that a subject can carry out {Jim wrote an article} {Maria bought a car}. Stative verbs, by contrast, express a state or condition, not an action {Jim has the article} {Maria owns a car}. Examples:

| Dynamic Verbs | Stative Verbs |

| argue | be |

| call | consider |

| drink | doubt |

| drive | dread |

| fly | enjoy |

| jump | exist |

| lift | hate |

| push | imagine |

| sew | imply |

| shout | know |

| sketch | need |

| taste | prefer |

| walk | seem |

| wash | suffer |

| watch | understand |

Only dynamic verbs can appear in the present-progressive tense {Jim is writing a book} and the past-progressive tense {Maria was buying a car}. Stative verbs simply don’t function idiomatically in those contexts.

141 Regular and irregular verbs.

The past-tense and past-participial forms of most English words are formed by appending -ed to the basic form {draft–drafted–drafted}. If the verb ends in -e, only a -d is appended {charge–charged–charged}. (Sometimes a final consonant is doubled: for the spelling rules of these regular forms, see § 174.) These verbs are classified as regular, or weak (the latter is a term used in philology to classify forms of conjugation).

But a few common verbs have maintained forms derived mostly from Old English roots {begin–began–begun} {bet–bet–bet} {bind–bound–bound} {bite–bit–bitten}. These verbs are called irregular or strong verbs. The various inflections of strong verbs defy simple classifications, but many past-tense and past-participial forms (1) change the vowel in the base verb (as begin), (2) keep the same form as the base verb (as bet), (3) share an irregular form (as bind), or (4) change endings (as bite). (The vowel change between cognate forms in category 1 is called an ablaut.) The verb be is highly irregular, with eight forms (is, are, was, were, been, being, be, and am). Because no system of useful classification is possible for irregular verbs, a reliable memory and a general dictionary are essential tools for using the correct forms consistently. Further complicating the spelling of irregular verbs is the fact that the form may vary according to the sense of the word. When used to mean “to offer a price,” for example, bid keeps the same form in the past tense and past participle, but when it means “to offer a greeting,” it forms bade (traditionally rhyming with glad) and bidden. The form may also depend on whether the verb is being used literally {wove a rug} or figuratively {weaved in traffic}. Finally, a few verbs that are considered regular have an alternative past tense and past participle that is formed by adding -t to the simple verb form {dream–dreamed} {dream–dreamt}. When these alternatives are available, AmE tends to prefer the forms ending in -ed (e.g., dreamed, learned, spelled), while BrE often prefers the forms ending in -t (dreamt, learnt, spelt).

The table below should be understood with those complications in mind. It lists only the irregular forms that are commonly used in Standard Written English. Words that may also take regular forms are italicized as a signal that the forms shown here may be incorrect in some usages. Irregular verbs are a closed word class, meaning that there is a finite number that can be exhaustively listed. (Other closed word classes include pronouns, articles, and auxiliary verbs. Regular verbs, on the other hand, are an example of an open word class—along with nouns, adjectives, and adverbs.) The list below, however, includes only the most common of the 270 or so irregular verbs. It also omits many words recently coined on the pattern of an old one (for instance, cablecast and simulcast, both formed on the analogy of broadcast). Those words almost always maintain the same inflections as the words they are built on.

It’s useful to read over this list with an eye to memorizing the inflections. Try the past-tense and past-participial forms in sentences that you can devise {I mistook your meaning}. Some may sound stuffy {I forbore attending the optional meeting}, but on the whole you’ll probably find it pleasing to be reminded of the standard inflections. Knowing them builds confidence in a speaker or writer.

A linking verb (also called a copula or connecting verb) is one that links the subject to a closely related word in the predicate—a subjective complement. The linking verb itself does not take an object because it expresses a state of being instead of an action {Mr. Block is the chief executive officer} {that snake is venomous} {his heart’s desire is to see his sister again}. There are two kinds of linking verbs: be-verbs and intransitive verbs that are used in a weakened sense, such as appear, become, feel, look, seem, smell, and taste. The weakened intransitive verbs often have a figurative sense akin to that of become, as in He fell heir to a large fortune (he didn’t physically fall on or into anything) or The river ran dry (a waterless river doesn’t run—it has dried up).

Some verbs only occasionally function as linking verbs—among them act {act weird}, get {get fat}, go {go bald}, grow {grow weary}, lie {lie fallow}, prove {prove untenable}, remain {remain quiet}, sit {sit still}, stay {stay trim}, turn {turn gray}, and wax {wax eloquent}. Also, some passive-voice constructions contain linking verbs {this band was judged best in the contest} {she was made sales-force manager}.

If a verb doesn’t have a subjective complement, then it doesn’t qualify as a linking verb in that particular construction. For instance, when a be-verb conveys the sense “to be situated” or “to exist,” it is not a linking verb {Kansas City, Kansas, is across the river} {there is an unfilled receptionist position}. Likewise, if a verb such as appear, feel, smell, sound, or taste is followed by an adverbial modifier instead of a subjective complement {he appeared in court} or a direct object {the dog smelled the scent}, it isn’t a linking verb.

A phrasal verb is usually a verb plus a preposition (or particle) {settle down} {act up} {phase out}. A phrasal verb is not hyphenated, even though its equivalent noun or phrasal adjective might be—e.g., compare to flare up with a flare-up, and compare to step up the pace with a stepped-up pace. Three rules apply: (1) if the phrasal verb has a sense distinct from the component words, use the entire phrase—e.g., hold up means “to rob” or “to delay,” and get rid of and do away with mean “to eliminate”; (2) avoid the phrasal verb if the verb alone conveys essentially the same meaning—e.g., rest up is equivalent to rest; and (3) don’t compress the phrase into a one-word verb, especially if it has a corresponding one-word noun form—e.g., one burns out (phrasal verb) and suffers burnout (noun).

Present-day phrasal verbs remain equally protean. A student who has had the maximum number of loans has “loaned out,” not the same as older “lend out” or more recent “max out” meaning “reach and pass one’s maximum performance”; cf. “veg [vej] out,” “become torpid as though in a vegetative state,” and “hulk out,” “go into a frenzy like the title character in the television series The Incredible Hulk.” A shampoo that “lathers in extra body and manageability” also exemplifies conversion (“lather” as verb) and phrasal verb. Phrasal verbs remain idiomatic, too: “in” and “out” are antonyms, but “fill in” and “fill out” (a blank or form) are virtually synonyms; while to be “all set up” is the opposite of “all upset.” Older “fall down” gives “downfall” but newer “melt down” and “fall out” give “meltdown” and “fallout”; likewise “breakthrough” and “kickback.” The verb/noun is “shoot out” but “shoot off” gives “offshoot.” The verb “take out” gives two nouns, “takeout” if it is food but “outtake” if it is edited film.

—W. F. Bolton

The Language of 1984

In a phrasal verb, the preposition is an integral part of the verb, serving as an adverb but often with a figurative, idiomatic sense:

• She turned up four new witnesses.

• Put out the candles.

• The interviewer took down everything she said verbatim. Although you might think at first that a preposition starts a prepositional phrase—that witnesses, candles, and everything are the objects of prepositions—that is not so. Grammatically, the nouns are direct objects of the verbs shaded in the above examples: in each sentence, the words up, out, and down could come after instead of before the noun:

• She turned four new witnesses up.

• Put the candles out.

• The interviewer took everything she said down verbatim.

Except in questions, prepositions can’t be switched around in this way. But in the following sentences, the preposition doesn’t function as part of the phrasal verb:

• She ran up the stairs.

• Several reporters walked out this door.

• He tumbled down the stairs.

Although an entire prepositional phrase can conceivably be moved {down the stairs he tumbled}, the single preposition can’t be moved in the way demonstrated above with phrasal verbs.

Although most phrasal verbs consist of two words {look over} {take up [= to begin as a hobby]}, many consist of three {get away with} {look up to} {put up with}.

144 Principal and auxiliary verbs.

Depending on its uses, a verb is classified as principal or auxiliary. A principal verb is one that can stand alone to express an act or state {he jogs} {I dreamed about Xanadu}. If combined with another verb, it expresses the combination’s leading thought {a tiger may roar}. An auxiliary verb is used with a principal verb to form a verb phrase that indicates mood, tense, or voice {you must study for the exam!} {I will go to the store} {the show was interrupted}. The most commonly used auxiliaries are be, can, do, have, may, must, ought, shall, and will. For more on auxiliary verbs, see §§ 198–209.

The combination of an auxiliary verb with a principal verb is a verb phrase, such as could happen, must go, or will be leaving. When a verb phrase is modified by an adverb, the modifier typically goes directly after the first auxiliary verb, as in could certainly happen, must always go, and will soon be leaving. The idea that verb phrases should not be “split” in this way is quite mistaken (see § 238). A verb phrase is negated by placing the negative adverb not after the first auxiliary {we have not called him}. In an interrogative sentence, the first auxiliary begins the sentence and is followed by the subject {must I repeat that?} {do you want more?}. An interrogative can be negated by placing not after the subject {do you not want more?}, but a contraction is often more natural {don’t you want more?}. Most negative forms can be contracted {we do not–we don’t} {I will not–I won’t} {he has not–he hasn’t} {she does not–she doesn’t}, but I am not is contracted to I’m not (never *I amn’t). The corresponding interrogative form is aren’t I? Sometimes the negative is emphasized if the auxiliary is contracted with the pronoun and the negative is left standing alone {he is not–he isn’t–he’s not} {we are not–we aren’t–we’re not} {they have not–they haven’t–they’ve not}.

Verb phrases are sometimes also called complete verbs. But this term can be ambiguous, since some grammarians use it instead for only the principal verb in a phrase. So in the sentence “We have not thanked him for working so hard,” complete verb could refer to have thanked or simply thanked. To further confuse the issue, others call any nonlinking finite verb a complete verb—meaning that working could also be a complete verb. Combine this ambiguity with the potential for conflating complete verb and complete predicate (see § 303), and it’s easy to see why this term is best avoided.

Most types of writing benefit from the use of contractions. If used thoughtfully, contractions in prose sound natural and relaxed, and make reading more enjoyable. Be-verbs and most of the auxiliary verbs are contracted when followed by not: are not–aren’t; was not–wasn’t; cannot–can’t; could not–couldn’t; do not–don’t; and so on. A few, such as ought not–oughtn’t, look or sound awkward and are best avoided. Pronouns can be contracted with auxiliaries, with forms of have, and with some be-verbs. Think before using one of the less common contractions, which often don’t work well in prose, except perhaps in dialogue or quotations. Some examples are I’d’ve (I would have), she’d’ve (she would have) it’d (it would), should’ve (should have), there’re (there are; there were), who’re (who are; who were), and would’ve (would have). Also, some contracted forms can have more than one meaning. For instance, there’s may be there is or there has, and I’d may be I had or I would. The particular meaning may not always be clear from the context.

Nouns can also form contractions with auxiliaries, have-verbs, and some be-verbs, but they often look and sound clumsy {you’d think the train’d be on time for once} {the stores’re sold out of fondue sets} {the DVDs’ve melted in the heat}. And nouns contracted with is may initially resemble possessives {Robin’s falling out of the tree} {Amalie’s firing the head chef right now}. Consider using a pronoun instead.

An infinitive verb, also called the verb’s root or stem, is a verb that in its principal uninflected form may be preceded by to {to dance} {to dive}. It is the basic form of the verb, the one listed in dictionary entries. The preposition to is sometimes called the “sign” of the infinitive {he tried to open the door}, and it is sometimes classed as an adverb (see § 210). In the active voice, to is generally dropped when the infinitive follows an auxiliary verb {you must flee} and can be dropped after several verbs, such as bid, dare, feel, hear, help, let, make, need, and see {you dare say that to me?}. But when the infinitive follows one of these verbs in the passive voice, to should be retained {he cannot be heard to deny it} {they cannot be made to listen}. The to should also be retained after ought and ought not (see § 203).

Although from about 1850 to 1925 many grammarians stated otherwise, it is now widely acknowledged that adverbs sometimes justifiably separate the to from the principal verb {they expect to more than double their income next year}. See § 238.

The infinitive has great versatility. It is sometimes called a verbal noun because it can function as part of a verb phrase {someone has to tell her} or a noun {to walk away now seems rash}. The infinitive also has limited uses as an adjective or an adverb. As a verb, it can take (1) a subject {we wanted the lesson to end}, (2) an object {try to throw the javelin higher}, (3) a predicate complement {want to race home?}, or (4) an adverbial modifier {you need to think quickly in chess}.

An infinitive takes on the role of principal verb when used with a finite verb whose sense doesn’t express a full thought, as often happens with dare, ought, am able, etc. {you ought to apologize to her} {I am finally able to laugh again}. Without the infinitive to express the specific obligation, ability, etc., such sentences make little sense. That’s why this use is termed the complementary infinitive: it completes the meaning of the finite verb, which takes on a modal quality {I am going to wash my hair tonight}. (This usage should not be confused with an infinitive operating as a subjective or objective complement, which is a noun or adjectival function.)

As a noun, the infinitive can perform as (1) the subject of a finite verb {to fly is a lofty goal} or (2) the object of a transitive verb or participle {I want to hire a new assistant}. An infinitive may be governed by a verb {cease to do evil}, a noun {we all have talents to be improved}, an adjective {she is eager to learn}, a participle {they are preparing to go}, or a pronoun {let him do it}.

An infinitive phrase can be used, often loosely, to modify a verb—in which case the sentence must have a grammatical subject (or an unexpressed subject of an imperative) that could logically perform the action of the infinitive. If there is none, then the sentence may be confusing. For example, in To repair your car properly, it must be sent to a mechanic, the infinitive repair does not have a logical subject; the infinitive phrase to repair your car is left dangling. But if the sentence is rewritten as To repair your car properly, you must take it to a mechanic, the logical subject is you.

A participle is a nonfinite verb that is not limited by person, number, or mood, but does have tense. Two participles are formed from the verb stem: the present participle invariably ends in -ing, and the past participle usually ends in -ed. See § 174.

The present participle consists of the present stem of the verb plus -ing {ask–asking}, sometimes with the final consonant of the stem doubled {spin–spinning}. It denotes the verb’s action as being in progress or incomplete at the time expressed by the sentence’s principal verb {watching intently for a mouse, the cat settled in to wait} {hearing his name, Jon turned to answer}.

The past participle is the third principal part of a verb. For a regular verb, it is formed by adding -d, -ed, or -t to the present stem and is identical with the past tense {call–called–called}. For irregular verbs, there are several patterns: the principal parts of the verb may be identical {slit–slit–slit}, the first and third parts may be identical {run–ran–run}, the second and third parts may be identical {spin–spun–spun}, or all three parts may be different {sing–sang–sung}. The past participle denotes the verb’s action as being completed {planted in the spring} {written last year}.

There are other types of participles as well. All verbs have a perfect participle {having called} and a perfect-progressive participle {having been calling}. Transitive verbs have passive forms of the present participle {being called} and of the perfect participle {having been called}.

Participles occur in many types of verb phrases. The past participle appears in the active-voice versions of the present perfect {have called}, the past perfect {had called}, and the future perfect {will have called}. It also appears in all tenses with the passive voice {was called} {were called} {am called}. See § 181 (verb conjugations with call).

152 Forming present participles.

The present participle is formed by adding -ing to the stem of the verb {reaping} {wandering}. If the stem ends in -ie, the -ie usually changes to -y before the -ing is added {die–dying} {tie–tying}. If the stem ends in a silent -e, that -e is usually dropped before the -ing is added {giving} {leaving}. There are two exceptions to this rule. The silent -e is retained when (1) the word ends with -oe {toe–toeing} {hoe–hoeing} {shoe–shoeing}, or (2) the verb has a participle that would resemble another word but for the distinguishing -e (e.g., dyeing means something different from dying, and singeing means something different from singing). The spelling rules for inflecting words that end in -y and for doubling final single consonants are the same as those given in § 174. Regular and irregular verbs both form the present participle in the same way. The present participle is the same for all persons and numbers.

With regular verbs, the past participle is formed in the same way as the past indicative—that is, the past-indicative and past-participial forms are always identical {stated–stated} {pulled–pulled}. For irregular verbs, the forms are sometimes the same {paid–paid} {sat–sat} and sometimes different {forsook–forsaken} {shrank–shrunk}. See § 141.

A participial phrase is made up of a participle plus any closely associated word or words, such as modifiers or complements. It can be used (1) as an adjective to modify a noun or pronoun {nailed to the roof, the slate stopped the leaks} {she pointed to the clerk drooping behind the counter}, or (2) as an absolute phrase {generally speaking, I prefer spicy dishes} {they having arrived, we went out on the lawn for our picnic}. For more on participial adjectives, see §§ 121–22, 129.

A gerund is a present participle used as a noun. It is not limited by person, number, or mood, but it does have tense. Being a noun, the gerund can be used as (1) the subject of a verb {complaining about it won’t help}; (2) the object of a verb {I don’t like your cooking}; (3) a predicate nominative or complement {his favorite pastime is sleeping}; or (4) the object of a preposition {reduce erosion by terracing the fields}. In some sentences, a gerund may substitute for an infinitive. Compare the use of the infinitive to lie as a noun {to lie is wrong} with the gerund lying {lying is wrong}.

Even though a gerund is always used as a noun, it retains some characteristics of a verb. Specifically, it can take an object {mailing letters kept her busy all day} and it can be modified by an adverb {preparing assiduously enabled him to succeed}.

A gerund phrase consists of a gerund, its object, and any modifiers that may be present {winning the bid amid so much competition made her proud}. The phrase in that example consists of the gerund winning, its object bid, the article (or adjective) the modifying bid, and the adverbial phrase amid so much competition. In addition to serving as the subject of a clause, a gerund phrase may function as:

• a direct object of a verb {we worried about his believing that idea};

• a subjective complement {that is throwing the baby out with the bathwater};

• an objective complement {we call this soldiering on};

• an adverbial objective {the offer is worth considering closely};

• the object of a preposition {they were amply rewarded for working overtime};

• an appositive {his strategy, being silent when there was no significant news, made everyone even more anxious}; or

• part of an absolute construction {her being honest about unpleasant facts having established trust with her opposite number, the two were able to proceed cooperatively}.

The same words may function as either a gerund phrase {knowing his own shortcomings made him more fearless as a competitor} or a participial phrase {knowing his own shortcomings, he decided to play it safe}.

157 Distinguishing between participles and gerunds.

Because participles and gerunds both derive from verbs, the difference between them depends on their function. A participle is used as a modifier {the running water} or as part of a verb phrase {the meter is running}; it can be modified only by an adverb {the swiftly running water}. A gerund is used as a noun {running is great exercise}; it can be modified only by an adjective {sporadic running and walking makes for a great workout}.

Along with infinitives, which can function as nouns {to lie is immoral} or modifiers {the decision to leave is always hard}, participles and gerunds are collectively called verbals. A phrase comprising more than one verbal is called a group verbal {hoping to change her mind was futile}.

As nouns, gerunds are modified by adjectives {double-parking is prohibited}, including possessive nouns and pronouns {Critt’s parking can be hazardous to pedestrians}. By contrast, a present participle is always modified (if at all) by an adverb, whether the participle serves as a verb {she’s parking the car now}, an adjective {I’ll be looking for a parking place}, or an adverb {finally parking, we saw that the store had already closed}. It is traditionally considered a linguistic fault (a fused participle) to use a nonpossessive noun or pronoun with a gerund:

Poor: *Me painting your fence depends on *you paying me first.

Better: My painting your fence depends on your paying me first.

In the poor example, me looks like the subject of the sentence, but it doesn’t agree with the verb depends. Instead, the subject is painting—a gerund, here seeming to be “modified” by me, a pronoun. In the predicate, you looks like the object of the preposition on, but the true object is the gerund paying.

There are times, however, when the possessive is unidiomatic. You usually have no choice but to use a fused participle with a nonpersonal noun {we’re not responsible for the jewelry having been mislaid}, a nonpersonal pronoun {we all insisted on something being done}, or a group of pronouns {the settlement depends on some of them agreeing to compromise}.

Both participles and gerunds are subject to dangling. A participle that has no syntactic relationship with the nearest subject is called a dangling participle or just a dangler. In effect, the participle ceases to function as a modifier and functions as a kind of preposition. Often the sentence is illogical, ambiguous, or even incoherent {*frequently used in early America, experts suggest that shaming is an effective punishment [used does not modify the closest noun, experts; it modifies shaming]} {*being a thoughtful mother, I believe Meg gives her children good advice [the writer at first seems to be attesting to his or her own thoughtfulness rather than Meg’s]}. Recasting the sentence so that the misplaced modifier is associated with the correct noun is the only effective cure {experts suggest that shaming, often used in early America, is an effective punishment} {I believe that because Meg is a thoughtful mother, she gives her children good advice}. Using passive voice in an independent clause can also produce a dangler. In *Finding that the questions were not ambiguous, the exam grades were not changed, the participle finding “dangles” because there is no logical subject to do the finding. The sentence can be corrected by using active voice instead of passive, so that the participle precedes the noun it modifies {finding that the questions were not ambiguous, the teacher did not change the exam grades}. Quite often writers will use it or there as the subject of the independent clause after a participial phrase, thereby producing a dangler without a logical subject {*reviewing the suggestions, it is clear that no consensus exists [a possible revision: Our review of the suggestions shows that no consensus exists]}.

When the participle in a dangling gerund is the object of a preposition, it functions as a noun rather than as a modifier. For example, *After finishing the research, the screenplay was easy to write (who did the research and who wrote the screenplay?). The best way to correct a dangling gerund is to revise the sentence. The example above could be revised as After Gero finished the research, the screenplay was easy to write, or After finishing the research, Gero found the screenplay easy to write. Dangling gerunds can result in improbable statements. Consider *while driving to San Antonio, my phone ran out of power. The phone wasn’t at the wheel, so driving is a dangling gerund that shouldn’t refer to my phone. Clarifying the subject of the gerund improves the sentence {while I was driving to San Antonio, my phone ran out of power}.

A verb has five properties: voice, mood, tense, person, and number. Verbs are conjugated (inflected) to show these properties.

Voice shows whether the subject acts (active voice) or is acted on (passive voice)—that is, whether the subject performs or receives the action of the verb. Only transitive verbs are said to have voice. The clause the judge levied a $50 fine is in the active voice because the subject judge is acting. But the tree’s branch was broken by the storm is in the passive voice because the subject branch does not break itself—it is acted on by the object storm. The passive voice is always formed by joining an inflected form of to be (or, in colloquial usage, get) with the verb’s past participle. Compare the ox pulls the cart (active voice) with the cart is pulled by the ox (passive voice). A passive-voice verb in a dependent clause often has an implied be-verb: in the advice given by the novelist, the implied words that was—omitted by what is known as a whiz-deletion (see § 315)—are understood to come before given; so the passive construction is was given. Although the be-verb is sometimes implied, the past participle must always be expressed. Sometimes the agent isn’t named {his tires were slashed}.

Passive voice will always have certain important uses, but remember that you must keep your eye on it at all times or it will drop its o and change swiftly from passive voice to passive vice.

—Lucille Vaughan Payne

The Lively Art of Writing

As a matter of style, passive voice {the matter will be given careful consideration} is typically, though not always, inferior to active voice {we will consider the matter carefully}. The choice between active and passive voice may depend on which point of view is desired. For instance, the mouse was caught by the cat describes the mouse’s experience, whereas the cat caught the mouse describes the cat’s.

What is important is to be able to identify passive voice reliably. Remember that be-verbs alone are not passive—hence he is thinking about his finances isn’t in the passive voice. It’s just a be-verb plus a present participle. To make it passive voice, you’d have to write his finances are thought about by him (an awkward sentence, to say the least). The two necessary elements are a be-verb (occasionally understood contextually) and a past participle:

Passive Voice

| is | misled |

| are | written |

| was | sent |

| were | demolished |

| been | built |

| being | completed |

| be | confirmed |

| am | bothered |

If the passive-voice verb is followed by the preposition by (plus the noun that performs the action), it is a long-passive construction. If the by-phrase is omitted, it is known as a short passive:

Long passive: Mistakes were made by our office.

Short passive: Mistakes were made.

Because of its vagueness, the short passive is sometimes (by no means always) used to evade or to deflect responsibility.

163 Progressive conjugation and voice.

If an inflected form of be is joined with a verb’s present participle, a progressive conjugation results {the ox is pulling the cart}. If the verb is transitive, the progressive conjugation is in active voice because the subject is performing the action, not being acted on. (See § 162.) But if both the principal verb and the auxiliary are be-verbs followed by a past participle {the cart is being pulled}, the result is a passive-voice construction.

Mood (or mode) indicates the manner in which the verb expresses an action or state of being. The three moods are indicative, imperative, and subjunctive.

The indicative mood is the most common in English. It is used to express facts and opinions and to ask questions {amethysts cost very little} {the botanist lives in a garden cottage} {does that bush produce yellow roses?}.

The imperative mood expresses commands {go away!}, direct requests {bring the tray in here}, and, sometimes, permission {come in!}. It is simply the verb’s stem used to make a command, a request, an exclamation, or the like {put it here!} {give me a clue} {help!}. The subject of the verb, you, is understood even though the sentence might include a direct address {give me the magazine} {Cindy, take good care of yourself [Cindy is a direct address, not the subject]}. Use the imperative mood cautiously: in some contexts it could be too blunt or unintentionally rude. You can soften the imperative by using a word such as please {please stop at the store}. If that isn’t satisfactory, you might recast the sentence in the indicative {will you stop at the store, please?}.

Although the subjunctive mood no longer appears with much frequency, it is useful when you want to express an action or a state not as a reality but as a mental conception. Typically, the subjunctive expresses an action or state as doubtful, imagined, desired, conditional, hypothetical, or otherwise contrary to fact. Despite its decline, the subjunctive mood persists in stock expressions such as perish the thought, heaven help us, or be that as it may. For particulars about subjunctive constructions, see the sections that follow.

168 Subjunctive vs. indicative mood.

The subjunctive mood signals a statement contrary to fact {if I were you}, including wishes {if I were a rich man}, conjectures {oh, were it so}, demands {the landlord insists that the dog go}, and suggestions {I recommend that she take a vacation}. Three errors often crop up with these constructions. First, writers sometimes use an indicative verb form when the subjunctive form is needed:

Poor: If it wasn’t for your help, I never would have found the place.

Better: If it weren’t for your help, I never would have found the place.

Second, indicative-mood sentences sometimes resemble these subjunctive constructions but aren’t statements contrary to fact:

Poor: I called to see whether she were in.

Better: I called to see whether she was in.

Third, one often sees *If I would have gone, I would . . . , with two conditionals, instead of If I had gone, I would. . . .

Although the subjunctive mood is often signaled by if, not every if takes a subjunctive verb. When the action or state might be true but the writer does not know, the indicative is called for instead of the subjunctive {if I am right about this, please call} {if Napoleon was in fact poisoned with arsenic, historians will need to reevaluate his associates}.

The present-tense subjunctive mood is formed by using the base form of the verb, such as be. This form of subjunctive often appears in suggestions or requirements {he recommended that we be ready at a moment’s notice} {we insist that he retain control of the accounting department}. The present-tense subjunctive is also expressed by using either be plus the simple-past form of the verb or a past-form auxiliary plus an infinitive {the chair proposed that the company be acquired by the employees through a stock-ownership plan} {today would be convenient for me to search for that missing file} {might he take down the decorations this afternoon?}.

Despite its label, the past-tense subjunctive mood refers to something in the present or future but contrary to fact. It is formed using the verb’s simple-past tense, except for be, which becomes were regardless of the subject’s number. For example, the declaration if only I had a chance expresses that the speaker has little or no chance. Similarly, I wish I were safe at home almost certainly means that the speaker is not at home and perhaps not safe—though it could also mean that the speaker is at home but quite unsafe.

This past-tense-but-present-sense subjunctive typically appears in the form if I (he, she, it) were {if I were king} {if she were any different}. That is, the subjunctive mood ordinarily uses a past-tense verb (e.g., were) to connote uncertainty, impossibility, or unreality where the present or future indicative would otherwise be used. Compare If I am threatened, I will quit (indicative) with If I were threatened, I would quit (subjunctive), or If the canary sings, I smile (indicative) with If the canary sang (or should sing, or were to sing), I would smile (subjunctive).

Just as the past subjunctive uses a verb’s simple-past-tense form to refer to the present or future, the past-perfect subjunctive uses a verb’s past-perfect form to refer to the past. The past-perfect subjunctive typically appears in the form if I (he, she, it) had been {if he had been there} {if I had gone}. That is, the subjunctive mood ordinarily uses a past-perfect verb (e.g., had been) to connote uncertainty or impossibility where the past or past-perfect indicative would otherwise be used. Compare If it arrived, it was not properly filed (indicative) with If it had arrived, it could have changed the course of history (subjunctive). The past-perfect subjunctive is identical in form to the past-perfect indicative, so the two can be distinguished only by context: if a past-perfect clause is followed by a conditional clause, the first clause is usually subjunctive as well. Compare If it had snowed the night before, then the children always made a snowman (indicative) with If it had snowed the night before, school would have been canceled (subjunctive).

Tense shows the time in which an act, state, or condition occurs or occurred. The three major divisions of time are present, past, and future. (Most modern grammarians hold that English has no future tense; see § 175.) Each division of time breaks down further into a perfect tense denoting a comparatively more remote time by indicating that the action has been completed: present perfect, past perfect, and future perfect. And all six of these tenses can be further divided into a progressive tense (also called imperfect or continuous), in which the action continues. (Rather than treating these as twelve distinct tenses, many modern grammarians classify the perfect and progressive as aspects, optional forms relating an action’s status—completed or ongoing—to the time expressed by one of the three main tenses.)

The present tense is the infinitive verb’s stem, also called the present indicative {walk} {drink}. It primarily denotes acts, conditions, or states that occur in the present {the dog howls} {the air is cold} {the water runs}. It is also used (1) to express a habitual action or general truth {cats prowl nightly} {polluted water is a health threat}; (2) to refer to timeless facts, such as memorable persons and works of the past that are still extant or enduring {Julius Caesar describes his strategies in The Gallic War} {the Pompeiian mosaics are exquisite}; and (3) to narrate a fictional work’s plot {the scene takes place aboard the Titanic}. The latter two uses are collectively referred to as the historical-present tense, and the third is especially important for those who write about literature. Characters in books, plays, and films do things—not did them. If you want to distinguish between present action and past action in literature, the present-perfect tense is helpful {Hamlet, who has spoken with his father’s ghost, reveals what he has learned to no one but Horatio}.

The present indicative is the verb stem for all persons, singular and plural, in the present tense—except for the third-person singular, which adds an -s to the stem {takes} {strolls} {says}. If the verb ends in -o, an -es is added {goes} {does} {torpedoes}. If the verb ends in a consonant followed by -y, the -y is changed to -i and then an -es is added {carry–carries} {identify–identifies} {multiply–multiplies}.

The past indicative denotes an act, state, or condition that occurred or existed at some explicit or implicit point in the past {the auction ended yesterday} {we returned the shawl}. For a regular verb, it is formed by adding -ed to its base form {jump–jumped} {spill–spilled}. If the verb ends in a silent -e, only a -d is added to form the past tense and past participle {bounce–bounced}. If it ends in -y preceded by a consonant, the -y changes to an -i before forming the past tense and past participle with -ed {hurry–hurried}. If it ends in a double consonant {block}, two vowels and a consonant {cook}, or a vowel other than -e {veto}, a regular verb forms the past tense and past participle by adding -ed to its simple form {block–blocked–blocked} {cook–cooked–cooked} {veto–vetoed–vetoed}.

If the verb ends in a single vowel before a consonant, several rules apply in determining whether the consonant is doubled. It is always doubled in one-syllable words {pat–patted–patted}. In words of more than one syllable, the final consonant is doubled if it is part of the syllable that is stressed both before and after the inflection {prefer–preferred–preferred}, but not otherwise {travel–traveled–traveled}. In BrE, there is no such distinction: all such consonants are doubled.

Irregular verbs form the past tense and past participle in various ways {give–gave–given} {hide–hid–hidden} {read–read–read}. See § 141.

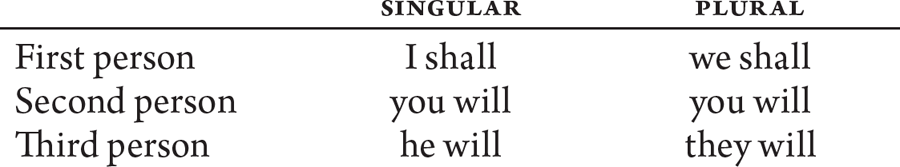

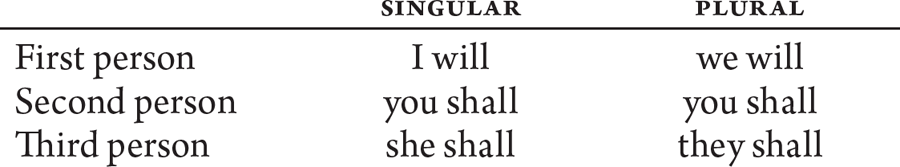

What is traditionally known as the future tense is formed by using will with the verb’s stem form {will walk} {will drink}. It refers to an expected act, state, or condition {the artist will design a wall mural} {the restaurant will open soon}. Shall may be used instead of will, but in AmE it typically appears only in first-person questions {shall we go?} and in legal requirements {the debtor shall pay within 30 days}. In most contexts, will is preferred—or must with legal requirements.

Two further points deserve mention here.

First, modern grammarians and linguists have generally repudiated the paradigm formerly taught in English grammar classes.

The Outmoded Shall–Will Paradigm

Simple Futurity

Determination, Promise, or Command

It was an artificial concoction that never reflected the actual English usage of any appreciable segment of English-speaking people.

Second, much more radically, most linguists are now convinced that, technically speaking, English has no future tense at all—that will is simply a modal verb that should be treated with all the others.4 Yet the future tense remains a part of traditional grammar and is discussed here in the familiar way.

The present-perfect tense is formed by using have or has with the principal verb’s past participle {have walked} {has drunk}. (Because all three perfect tenses use a form of have plus a past participle, they are called compound tenses.) It is formed the same way in both the indicative and subjunctive moods (see §§ 167–68), and in both it denotes an act, state, or condition that is now completed or continues up to the present {I have put away the clothes} {it has been a long day} {I will apologize, even if I have done nothing wrong}. The present perfect is distinguished from the past tense because it refers to (1) a time in the indefinite past {I have played golf there before} or (2) a past action that comes up to and touches the present {I have played cards for the last 18 hours}. The past tense, by contrast, indicates a more specific or a more remote time in the past.

The present-perfect tense is often used with the adverb always. “I have always hoped that he would behave better.” “I have always believed that good may come out of evil.” “I have always hoped that one day I may become rich.”

—W. P. Jowett

Chatting About English

The past-perfect (or pluperfect) tense is formed by using had with the principal verb’s past participle {had walked} {had drunk}. It refers to an act, state, or condition that was completed before another specified or implicit past time or past action {the engineer had driven the train to the roundhouse before we arrived} {by the time we stopped to check the map, the rain had begun falling} {the movie had already ended}.

The future-perfect tense is formed by using will have with the verb’s past participle {will have walked} {will have drunk}. It refers to an act, state, or condition that is expected to be completed before some other future act or time {the entomologist will have collected 60 more specimens before the semester ends} {the court will have adjourned by five o’clock}. Shall can also form the future perfect, but usually only for the first person, and in very few parts of the English-speaking world is it prevalent {I shall have finished by tomorrow} {we shall have written before we embark}.

The progressive tenses, also known as continuous tenses, show action that progresses or continues. With active-voice verbs, all six basic tenses can be made progressive by using the appropriate be-verb and the present participle of the main verb, as so:

• present progressive {he is playing tennis};

• present-perfect progressive {he has been playing tennis};

• past progressive {he was playing tennis};

• past-perfect progressive {he had been playing tennis};

• future progressive {he will be playing tennis}; and

• future-perfect progressive {he will have been playing tennis}.

Any such tense requiring additional words for its expression is considered an expanded tense.

With the passive voice, the present- and past-progressive tenses are made by using the appropriate be-verb with the present participle being, plus the past participle of the main verb, as so:

• present {I am being dealt the cards}; and

• past {I was being dealt the cards}.

Progressive tenses frequently appear in the posing and answering of questions {Are you studying? No, I’m answering e-mails}.

180 Backshifting in reported speech.

When one speaker or writer conveys the words of another, grammarians call the result reported speech. There are two types of reported speech: direct and indirect speech (also called direct and indirect discourse). Direct speech repeats another’s words verbatim (or at least purports to), usually in the form of a quotation {he said, “I’ve never come here by this route”}. Indirect speech, on the other hand, conveys the content but not the form—that is, it paraphrases the original utterance without quoting the exact words {he said he had never gone there by that route}.

Notice that in the second example, several words from the original statement have changed. That’s because indirect discourse reflects the reporting speaker’s deixis—the reporter’s perspective on identity, time, and place. So pointing elements in the original utterance shift accordingly: verbs and pronouns shift in person (I becomes he), and references to location shift in relation to distance (here becomes there; this becomes that; even come becomes go)—unless the identity or location of the reporter and the original speaker are the same. References to time usually become more remote (now becomes then)—unless the original utterance was a future reference to the time when something will be reported {“I’ll call you then” → she said she’d call me now} or the original speaking and the reporting happen in the same window of time {“I am here now” → he says he is here now}.

This shift in time is particularly important for verb tense. Indirect speech typically involves backshifting—the changing of present-tense to past-tense verbs when currently relating what someone earlier said in the present tense. Since the reporting clause uses the past tense (he said), the verbs in the original utterance must become more remote in the reported clause (the present-perfect have come becomes the past-perfect had gone). Grammarians call this relationship, in which the verb tense of the reporting clause governs that of the reported clause, the sequence of tenses. Exactly what tense a reported verb backshifts to is dictated by context. When the reporting clause is in the present tense, backshifting is unnecessary {“we want to leave” → they say they want to leave}. And sometimes the backshift is either impossible (past-perfect verbs cannot become any more remote) or optional. For instance, I have walked 12 miles today becomes (at a later time) he said he had walked 12 miles that day. But I have tried a thousand times could become either he said he had tried a thousand times or he said he has tried a thousand times. Backshifting also occurs in sentences with hypothetical conditional clauses (see § 312).

181 Conjugation of the regular verb “to call.”

Principal parts: call, called, called

| INFINITIVES | Active | Passive |

| Present | to call | to be called |

| Present progressive | to be calling | |

| Perfect (present perfect) | to have called | to have been called |

| Perfect progressive | to have been calling | |

| PARTICIPLES | Active | Passive |

| Present | calling | being called |

| Perfect (present perfect) | having called | having been called |

| Perfect progressive | having been calling | |

| Past | called | |

| GERUNDS | Active | Passive |

| Present | calling | being called |

| Perfect (present perfect) | having called | having been called |

| Perfect progressive | having been calling |

| Singular | Plural |

PRESENT TENSE

| I call | we call |

| you call | you call |

| he calls | they call |

PRESENT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I am calling | we are calling |

| you are calling | you are calling |

| he is calling | they are calling |

PRESENT-EMPHATIC TENSE

| I do call | we do call |

| you do call | you do call |

| he does call | they do call |

PRESENT-PERFECT TENSE

| I have called | we have called |

| you have called | you have called |

| he has called | they have called |

PRESENT-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I have been calling | we have been calling |

| you have been calling | you have been calling |

| he has been calling | they have been calling |

PAST TENSE

| I called | we called |

| you called | you called |

| he called | they called |

PAST-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I was calling | we were calling |

| you were calling | you were calling |

| he was calling | they were calling |

PAST-EMPHATIC TENSE

| I did call | we did call |

| you did call | you did call |

| he did call | they did call |

PAST-PERFECT TENSE

| I had called | we had called |

| you had called | you had called |

| he had called | they had called |

PAST-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I had been calling | we had been calling |

| you had been calling | you had been calling |

| he had been calling | they had been calling |

FUTURE TENSE

| I will call | we will call |

| you will call | you will call |

| he will call | they will call |

FUTURE-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I will be calling | we will be calling |

| you will be calling | you will be calling |

| he will be calling | they will be calling |

FUTURE-PERFECT TENSE

| I will have called | we will have called |

| you will have called | you will have called |

| he will have called | they will have called |

FUTURE-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I will have been calling | we will have been calling |

| you will have been calling | you will have been calling |

| he will have been calling | they will have been calling |

Indicative Mood, Passive Voice

PRESENT TENSE

| I am called | we are called |

| you are called | you are called |

| he is called | they are called |

PRESENT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I am being called | we are being called |

| you are being called | you are being called |

| he is being called | they are being called |

PRESENT-PERFECT TENSE

| I have been called | we have been called |

| you have been called | you have been called |

| he has been called | they have been called |

PAST TENSE

| I was called | we were called |

| you were called | you were called |

| he was called | they were called |

PAST-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I was being called | we were being called |

| you were being called | you were being called |

| he was being called | they were being called |

PAST-PERFECT TENSE

| I had been called | we had been called |

| you had been called | you had been called |

| he had been called | they had been called |

FUTURE TENSE

| I will be called | we will be called |

| you will be called | you will be called |

| he will be called | they will be called |

FUTURE-PERFECT TENSE

| I will have been called | we will have been called |

| you will have been called | you will have been called |

| he will have been called | they will have been called |

Imperative Mood, Active Voice

PRESENT TENSE

| call | call |

PRESENT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| be calling | be calling |

PRESENT-EMPHATIC TENSE

| do call | do call |

Imperative Mood, Passive Voice

PRESENT TENSE

| be called | be called |

Subjunctive Mood, Active Voice

| Singular | Plural |

PRESENT TENSE

| I call | we call |

| you call | you call |

| he call | they call |

PRESENT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I be calling | we be calling |

| you be calling | you be calling |

| he be calling | they be calling |

PRESENT-EMPHATIC TENSE

| I do call | we do call |

| you do call | you do call |

| he do call | they do call |

PRESENT-PERFECT TENSE

| I have called | we have called |

| you have called | you have called |

| he have called | they have called |

PRESENT-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I have been calling | we have been calling |

| you have been calling | you have been calling |

| he have been calling | they have been calling |

PAST TENSE

| I called | we called |

| you called | you called |

| he called | they called |

PAST-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I were calling | we were calling |

| you were calling | you were calling |

| he were calling | they were calling |

PAST-EMPHATIC TENSE

| I did call | we did call |

| you did call | you did call |

| he did call | they did call |

PAST-PERFECT TENSE

| I had called | we had called |

| you had called | you had called |

| he had called | they had called |

PAST-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I had been calling | we had been calling |

| you had been calling | you had been calling |

| he had been calling | they had been calling |

PAST-CONDITIONAL TENSE

| had I called | had we called |

| had you called | had you called |

| had he called | had they called |

FUTURE TENSE

| I should call | we should call |

| you should call | you should call |

| he should call | they should call |

FUTURE-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I should be calling | we should be calling |

| you should be calling | you should be calling |

| he should be calling | they should be calling |

FUTURE-PERFECT TENSE

| I should have called | we should have called |

| you should have called | you should have called |

| he should have called | they should have called |

FUTURE-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I should have been calling | we should have been calling |

| you should have been calling | you should have been calling |

| he should have been calling | they should have been calling |

Subjunctive Mood, Passive Voice

PRESENT TENSE

| I be called | we be called |

| you be called | you be called |

| he be called | they be called |

PRESENT-PERFECT TENSE

| I have been called | we have been called |

| you have been called | you have been called |

| he have been called | they have been called |

PAST TENSE

| I were called | we were called |

| you were called | you were called |

| he were called | they were called |

PAST-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I were being called | we were being called |

| you were being called | you were being called |

| he were being called | they were being called |

PAST-PERFECT TENSE

| I had been called | we had been called |

| you had been called | you had been called |

| he had been called | they had been called |

PAST-CONDITIONAL TENSE

| had I been called | had we been called |

| had you been called | had you been called |

| had he been called | had they been called |

FUTURE TENSE

| I should be called | we should be called |

| you should be called | you should be called |

| he should be called | they should be called |

FUTURE-PERFECT TENSE

| I should have been called | we should have been called |

| you should have been called | you should have been called |

| he should have been called | they should have been called |

182 Conjugation of the irregular verb “to hide.”

Principal parts: hide, hid, hidden

Indicative Mood, Active Voice

| Singular | Plural |

PRESENT TENSE

| I hide | we hide |

| you hide | you hide |

| he hides | they hide |

PRESENT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I am hiding | we are hiding |

| you are hiding | you are hiding |

| he is hiding | they are hiding |

PRESENT-EMPHATIC TENSE

| I do hide | we do hide |

| you do hide | you do hide |

| he does hide | they do hide |

PRESENT-PERFECT TENSE

| I have hidden | we have hidden |

| you have hidden | you have hidden |

| he has hidden | they have hidden |

PRESENT-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I have been hiding | we have been hiding |

| you have been hiding | you have been hiding |

| he has been hiding | they have been hiding |

PAST TENSE

| I hid | we hid |

| you hid | you hid |

| he hid | they hid |

PAST-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I was hiding | we were hiding |

| you were hiding | you were hiding |

| he was hiding | they were hiding |

PAST-EMPHATIC TENSE

| I did hide | we did hide |

| you did hide | you did hide |

| he did hide | they did hide |

PAST-PERFECT TENSE

| I had hidden | we had hidden |

| you had hidden | you had hidden |

| he had hidden | they had hidden |

PAST-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I had been hiding | we had been hiding |

| you had been hiding | you had been hiding |

| he had been hiding | they had been hiding |

FUTURE TENSE

| I will hide | we will hide |

| you will hide | you will hide |

| he will hide | they will hide |

FUTURE-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I will be hiding | we will be hiding |

| you will be hiding | you will be hiding |

| he will be hiding | they will be hiding |

FUTURE-PERFECT TENSE

| I will have hidden | we will have hidden |

| you will have hidden | you will have hidden |

| he will have hidden | they will have hidden |

FUTURE-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I will have been hiding | we will have been hiding |

| you will have been hiding | you will have been hiding |

| he will have been hiding | they will have been hiding |

Indicative Mood, Passive Voice

PRESENT TENSE

| I am hidden | we are hidden |

| you are hidden | you are hidden |

| he is hidden | they are hidden |

PRESENT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I am being hidden | we are being hidden |

| you are being hidden | you are being hidden |

| he is being hidden | they are being hidden |

PRESENT-PERFECT TENSE

| I have been hidden | we have been hidden |

| you have been hidden | you have been hidden |

| he has been hidden | they have been hidden |

PAST TENSE

| I was hidden | we were hidden |

| you were hidden | you were hidden |

| he was hidden | they were hidden |

PAST-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I was being hidden | we were being hidden |

| you were being hidden | you were being hidden |

| he was being hidden | they were being hidden |

PAST-PERFECT TENSE

| I had been hidden | we had been hidden |

| you had been hidden | you had been hidden |

| he had been hidden | they had been hidden |

FUTURE TENSE

| I will be hidden | we will be hidden |

| you will be hidden | you will be hidden |

| he will be hidden | they will be hidden |

FUTURE-PERFECT TENSE

| I will have been hidden | we will have been hidden |

| you will have been hidden | you will have been hidden |

| he will have been hidden | they will have been hidden |

Imperative Mood, Active Voice

PRESENT TENSE

| hide | hide |

PRESENT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| be hiding | be hiding |

PRESENT-EMPHATIC TENSE

| do hide | do hide |

Imperative Mood, Passive Voice

| Singular | Plural |

PRESENT TENSE

| be hidden | be hidden |

Subjunctive Mood, Active Voice

PRESENT TENSE

| I hide | we hide |

| you hide | you hide |

| he hide | they hide |

PRESENT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I be hiding | we be hiding |

| you be hiding | you be hiding |

| he be hiding | they be hiding |

PRESENT-EMPHATIC TENSE

| I do hide | we do hide |

| you do hide | you do hide |

| he do hide | they do hide |

PRESENT-PERFECT TENSE

| I have hidden | we have hidden |

| you have hidden | you have hidden |

| he have hidden | they have hidden |

PRESENT-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I have been hiding | we have been hiding |

| you have been hiding | you have been hiding |

| he have been hiding | they have been hiding |

PAST TENSE

| I hid | we hid |

| you hid | you hid |

| he hid | they hid |

PAST-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I were hiding | we were hiding |

| you were hiding | you were hiding |

| he were hiding | they were hiding |

PAST-EMPHATIC TENSE

| I did hide | we did hide |

| you did hide | you did hide |

| he did hide | they did hide |

PAST-PERFECT TENSE

| I had hidden | we had hidden |

| you had hidden | you had hidden |

| he had hidden | they had hidden |

PAST-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I had been hiding | we had been hiding |

| you had been hiding | you had been hiding |

| he had been hiding | they had been hiding |

PAST-CONDITIONAL TENSE

| had I hidden | had we hidden |

| had you hidden | had you hidden |

| had he hidden | had they hidden |

FUTURE TENSE

| I should hide | we should hide |

| you should hide | you should hide |

| he should hide | they should hide |

FUTURE-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I should be hiding | we should be hiding |

| you should be hiding | you should be hiding |

| he should be hiding | they should be hiding |

FUTURE-PERFECT TENSE

| I should have hidden | we should have hidden |

| you should have hidden | you should have hidden |

| he should have hidden | they should have hidden |

FUTURE-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I should have been hiding | we should have been hiding |

| you should have been hiding | you should have been hiding |

| he should have been hiding | they should have been hiding |

Subjunctive Mood, Passive Voice

| Singular | Plural |

PRESENT TENSE

| I be hidden | we be hidden |

| you be hidden | you be hidden |

| he be hidden | they be hidden |

PRESENT-PERFECT TENSE

| I have been hidden | we have been hidden |

| you have been hidden | you have been hidden |

| he have been hidden | they have been hidden |

PAST TENSE

| I were hidden | we were hidden |

| you were hidden | you were hidden |

| he were hidden | they were hidden |

PAST-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I were being hidden | we were being hidden |

| you were being hidden | you were being hidden |

| he were being hidden | they were being hidden |

PAST-PERFECT TENSE

| I had been hidden | we had been hidden |

| you had been hidden | you had been hidden |

| he had been hidden | they had been hidden |

PAST-CONDITIONAL TENSE

| had I been hidden | had we been hidden |

| had you been hidden | had you been hidden |

| had he been hidden | had they been hidden |

FUTURE TENSE

| I should be hidden | we should be hidden |

| you should be hidden | you should be hidden |

| he should be hidden | they should be hidden |

FUTURE-PERFECT TENSE

| I should have been hidden | we should have been hidden |

| you should have been hidden | you should have been hidden |

| he should have been hidden | they should have been hidden |

183 Conjugation of the verb “to be.”

The verb be has eight forms (be, is, are, was, were, been, being, and am) and has several special uses. First, it is sometimes a sentence’s principal verb meaning “exist” {I think, therefore I am}. Second, it is more often used as an auxiliary verb {I was born in Lubbock}. When joined with a verb’s present participle, it denotes continuing or progressive action {the train is coming} {the passenger was waiting}. When joined with a past participle, the verb becomes passive {a signal was given} {an earring was dropped} (see § 162). Often this type of construction can be advantageously changed to active voice {he gave the signal} {she dropped her earring}. Third, be is the most common linking verb that connects the subject with something affirmed of the subject {truth is beauty} {we are the champions}. Occasionally a be-verb is used as part of an adjective {a wannabe rock star [want to be]} {a would-be hero} or noun {a has-been}.

Be has some nuances in the way it’s conjugated. (1) The stem is not used in the present-indicative form. Instead, be has three forms: for the first-person singular, am; for the third-person singular, is; and for all other persons, are. (2) The present participle is formed by adding -ing to the root be {being}. It is the same for all persons, but the present progressive requires also using am, is, or are {I am being} {it is being} {you are being}. (3) The past indicative has two forms: the first- and third-person singular use was; all other persons use were {she was} {we were}. (4) The past participle for all persons is been {I have been} {they have been}. (5) The imperative is the verb’s stem {be yourself!}.

Principal parts: be, been, been

INFINITIVES

| Present | to be |

| Perfect (present perfect) | to have been |

PARTICIPLES

| Present | being |

| Perfect (present perfect) | having been |

| Past | been |

GERUNDS

| Present | being |

| Perfect (present perfect) | having been |

| Singular | Plural |

PRESENT TENSE

| I am | we are |

| you are | you are |

| he is | they are |

PRESENT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I am being | we are being |

| you are being | you are being |

| he is being | they are being |

PRESENT-PERFECT TENSE

| I have been | we have been |

| you have been | you have been |

| he has been | they have been |

PRESENT-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I have been being | we have been being |

| you have been being | you have been being |

| he has been being | they have been being |

PAST TENSE

| I was | we were |

| you were | you were |

| he was | they were |

PAST-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I was being | we were being |

| you were being | you were being |

| he was being | they were being |

PAST-PERFECT TENSE

| I had been | we had been |

| you had been | you had been |

| he had been | they had been |

PAST-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I had been being | we had been being |

| you had been being | you had been being |

| he had been being | they had been being |

FUTURE TENSE

| I will be | we will be |

| you will be | you will be |

| he will be | they will be |

FUTURE-PERFECT TENSE

| I will have been | we will have been |

| you will have been | you will have been |

| he will have been | they will have been |

Imperative Mood

PRESENT TENSE

| be | be |

Subjunctive Mood

PRESENT TENSE

| I be | we be |

| you be | you be |

| he be | they be |

PRESENT-PERFECT TENSE

| I have been | we have been |

| you have been | you have been |

| he have been | they have been |

PRESENT-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I have been being | we have been being |

| you have been being | you have been being |

| he have been being | they have been being |

PAST TENSE

| I were | we were |

| you were | you were |

| he were | they were |

PAST-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I were being | we were being |

| you were being | you were being |

| he were being | they were being |

PAST-PERFECT TENSE

| I had been | we had been |

| you had been | you had been |

| he had been | they had been |

PAST-PERFECT-PROGRESSIVE TENSE

| I had been being | we had been being |

| you had been being | you had been being |

| he had been being | they had been being |

FUTURE-PERFECT TENSE

| I should have been | we should have been |

| you should have been | you should have been |

| he should have been | they should have been |

FUTURE TENSE

| I should be | we should be |

| you should be | you should be |

| he should be | they should be |

CONDITIONAL TENSE

| had I been | had we been |

| had you been | had you been |

| had he been | had they been |

A verb’s person shows whether the act, state, or condition is that of (1) the person speaking (first person), (2) the person spoken to (second person), or (3) the person or thing spoken of (third person).

The number of a verb must agree with the number of the noun or pronoun used with it. In other words, the verb must be singular or plural. Only the third-person present-indicative singular changes form to indicate number and person {I sketch} {you sketch} {she sketches} {they sketch}. (Be changes form in a few other contexts, however [see § 183]. And most modal auxiliaries lack a distinct third-person-singular form.) The second-person verb is always plural in form, whether one person or more than one person is spoken to {you are a wonderful person} {you are wonderful people}.

186 Agreement in person and number.

A finite verb agrees with its subject in person and number—which is to say that a singular subject takes a singular verb {the solution works}, while a plural subject takes a plural verb {the solutions work}. When a verb has two or more subjects connected by and, it agrees with them jointly and is plural {Socrates and Plato were wise}. When a verb has two or more subjects connected by or or nor, the verb agrees with the last-named subject {Bob or his friends have your key} {neither the twins nor Jon is prepared to leave}. When the subject is a collective noun conveying the idea of unity or multitude, the verb is singular {the nation is powerful}. When the subject is a collective noun conveying the idea of plurality, the verb is plural {the faculty were divided in their sentiments}.

This last type of construction, in which meaning rather than strict grammar governs syntax, is called synesis or notional concord. In English, synesis occurs when a grammatically singular subject takes a plural verb. (Synesis applies to pronouns, too: note the use of their to refer to faculty above and to team, total, and bulk below.) This is more common in BrE than AmE, but it appears in all varieties of the language—most often with collective nouns {the team were honing their skills}. But many other nouns such as number, total, lot, multitude, myriad, and majority can also function as plural when followed by an of-phrase using a plural noun {a majority of senators support the bill} {a number of people were there} {a total of 37 students have voiced their concerns}. These nouns of multitude are usually treated as singular when they are preceded by the definite article, when the of-phrase uses a singular mass noun, or when they appear without an of-phrase {the number of people was staggering} {a lot of this chicken has gone bad} {a majority is more than we can hope for}.

But there are exceptions: sometimes the of-phrase is implied or displaced {over a hundred demonstrators turned out; a lot [of the demonstrators] were carrying signs} {of those present, only a minority were against the proposition}. And sometimes the sense is plural even when the precedes the noun {the bulk of librarians say their work is fulfilling}. The deciding factor is whether the focus is on the subject as a single cohesive entity or as a group of individual elements (though sometimes either option is appropriate {a multitude of options confront the customer [focusing on the individual options]} {a multitude of options confronts the customer [focusing on the total number of options]}). See §§ 10–13.

Likewise, a plural subject indicating a quantity of something considered as a unit takes a singular verb {three hundred dollars is a reasonable price} {six weeks is a long time to wait} {three-quarters of the grain was infested}. But if the plural subject represents a number of individual items, then the verb is plural {three hundred tourists were enrolled in the excursion} {six weeks have passed since the accident} {two-thirds of the flowers were destroyed}.

A book or film title incorporating a plural, or a plural word referred to as a word, is considered singular and takes a singular verb {The Replacements is her favorite movie} {errata is the plural of erratum}.

A gerund, an infinitive, or a clause used as a subject ordinarily requires a singular verb {her negotiating wins over many a client} {to succeed is to thrive} {what this house needs is a new coat of paint}. Some gerunds, however, have well-accepted plural forms that take plural verbs {beginnings always present a challenge} {her musings were a delight to everyone}.

187 Disjunctive compound subjects.

When two or more discrete subjects of mixed number (i.e., not all singular or plural) are joined with a disjunctive such as or, either–or, or neither–nor, the verb should agree with the nearest subject:

Poor: Either the teachers or the school board have the authority to act.

Better: Either the teachers or the school board has the authority to act.

Better: Either the school board or the teachers have the authority to act.

As the second “better” example shows, placing the plural subject closest to the verb makes the sentence sound more natural.

188 Conjunctive compound subjects.

When two singular subjects are joined by a conjunctive such as and, the verb should be plural. The common error here is to ignore the compound nature of the subject:

Poor: Public relations and recruiting is a big part of the coach’s job.

Better: Public relations and recruiting are a big part of the coach’s job.

Notice that the plural subject (public relations and recruiting) determines the number of the verb—not the singular complement (a big part).

Two exceptions. First, if the subjects are not discrete but instead refer to a single thing, use a singular verb {corned beef and cabbage is the traditional St. Patrick’s Day fare} {spaghetti and meatballs is her favorite dish}. A singular verb may also be appropriate when the subjects are rhetorically close {fame and fortune was her goal}. But this is often a matter of idiom {time and tide wait for no one}. Second, if each or every modifies singular subjects joined by and, the verb is singular {each box, suitcase, and handbag is inspected}.

189 Some other nuances of number involving conjunctions.