Make the Moor thank me, love me, and reward me for making him egregiously an ass.

Iago

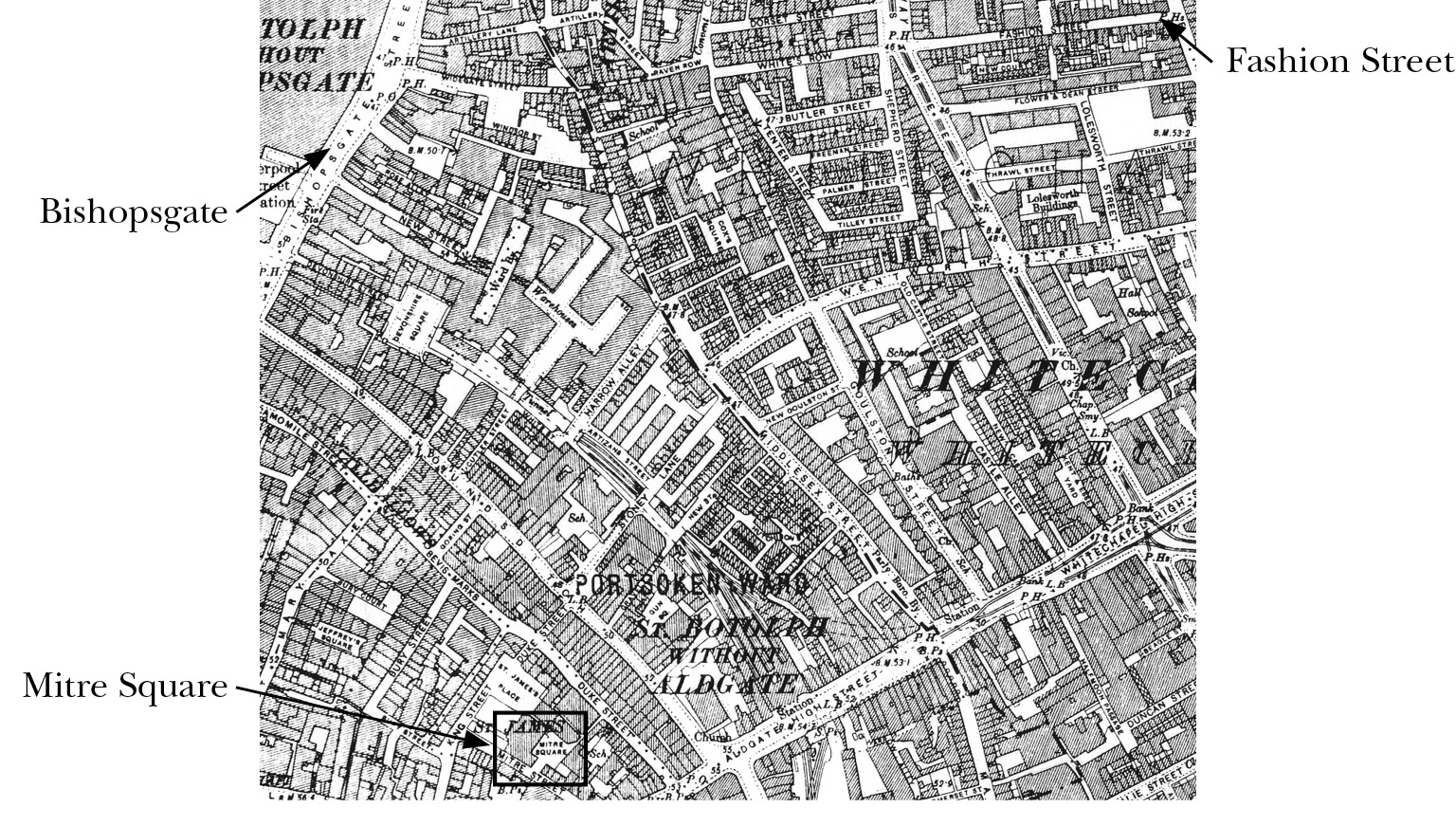

Complementing ‘Juwes’, there was another funny little Masonic jest for Charlie Warren about a mile away from Goulston Street. When Catherine Eddowes was released from her lock-up at Bishopsgate police station, she asked the duty officer what time it was. Just before one o’clock, he replied – ‘Too late for you to get another drink.’ Somewhat the worse for wear, she vanished out of the police station with the stated intention of going home.

Eddowes lived at number 6 Fashion Street, an inappropriately named Whitechapel slum directly east of Bishopsgate.1

By any assessment, the place of her death was not on her way home. Around some corner the most dangerous man in London was looking for just such a sweetheart, and in his company Eddowes walked away from Fashion Street and directly south. At any turn in this gloomy labyrinth he could have chosen to kill her. Instead he escorted her to a location of gaslight and multiple windows in which, if anything, he was actually more exposed.

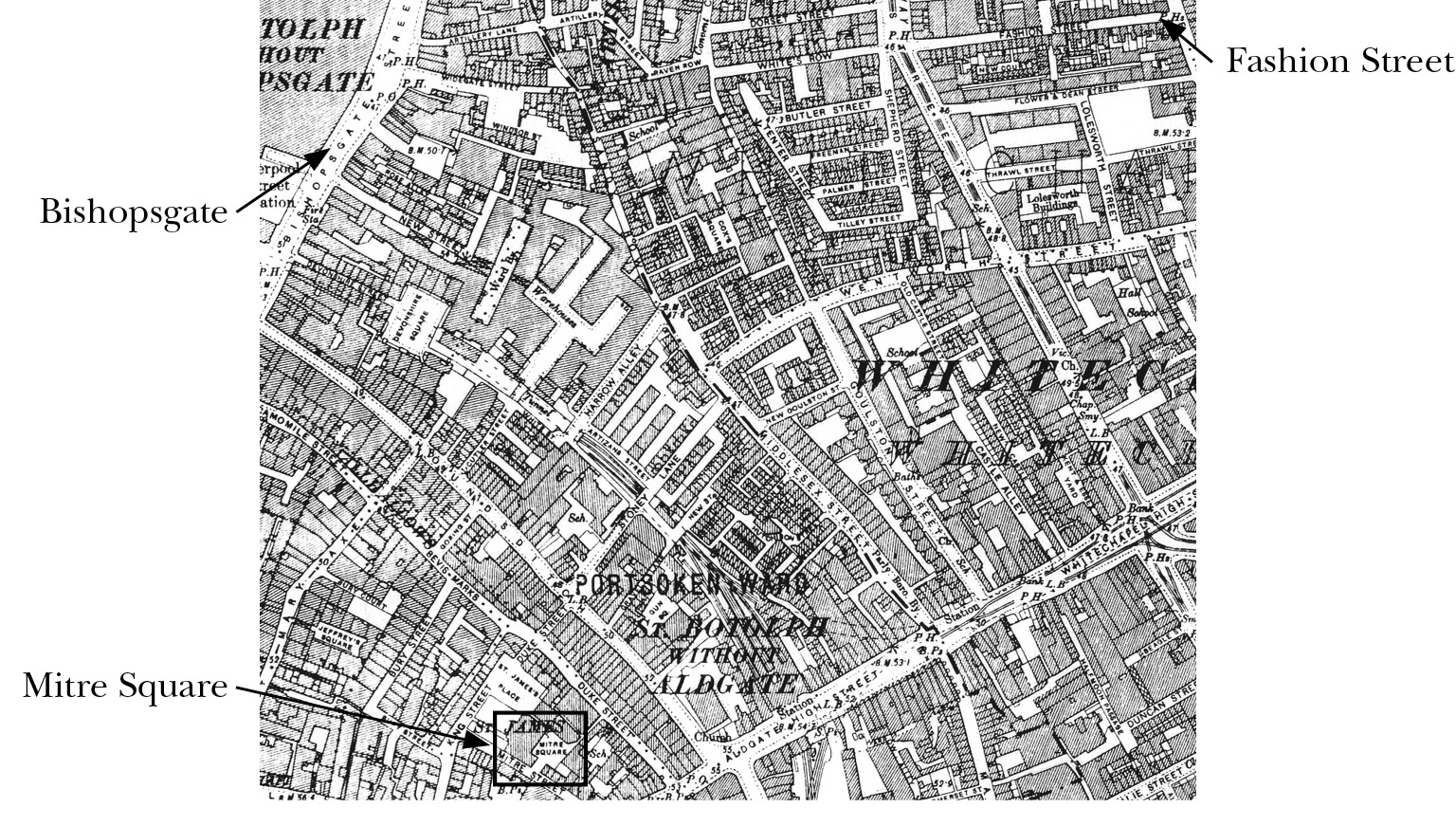

In my view, her assassin took her to Mitre Square ‘by design’, as a requisite of his ‘Funny Little Game’. Cutting compasses into her face up some anonymous back alley would not have conjured the symbolism he was after. What Jack wanted to leave as ‘his fearful sign manual’2 was the ubiquitous and most recognisable Masonic icon of them all, ‘compasses on the square’.

Eddowes was initiated into the ‘Funny Little Game’ with the full Jubelo – her throat cut across, entrails hauled out, and all metal removed. ‘The intestines were drawn out to a large extent and placed over the right shoulder,’ deposed Dr Gordon Brown at the inquest. ‘A piece of about two feet was quite detached from the body and placed between the body and the left arm.’

CITY SOLICITOR: By ‘placed’, do you mean put there by design?

BROWN: Yes.

Yet we’re enjoined to believe that the symbols carved into Eddowes’ face are a meaningless afterthought. That you can ‘design’ with flopping intestines, but not with the point of a knife. That you can carry a piece of this woman’s apron as a beacon for a message, and then write something above it of no discernible meaning or consequence, and that ‘Juwes’ and a Mason’s Mark are indecipherable abstractions.

Two slayings that night meant two concurrent but quite separate coroners’ courts. The City was an independent entity, responsible to the Corporation of London, and immune to interference from the Home Office and the Metropolitan Police. The Met couldn’t manipulate and control this court as it was to manipulate and make preposterous the inquest into the death of Elizabeth Stride.

City Coroner S.F. Langham, a sixty-five-year-old blueblood behind rectitudinous pince-nez, had spent his entire professional life listening to stories of the dead. First appointed Deputy Coroner for Westminster in 1849, he moved to the City, where he was promoted to Boss Coroner in 1884. His official address was ‘Coroner’s Office, City Mortuary, Golden Lane’,3 and it was here on 4 October 1888 that the inquest into the murder of Catherine Eddowes began. Proceedings were watched by Inspector McWilliam and Assistant Commissioner Smith himself.

The attendance of such eminent spectators is perhaps indicative of the importance the City attached to the case, further underlined by the presence of its thirty-eight-year-old star solicitor. Henry Homewood Crawford was one of the smartest brains on the block. A polyglot, a musician and a talented amateur actor, in the words of a contemporary biography, ‘He may fittingly be described as Attorney General of the City. He is legal advisor to the Right Hon the Lord Mayor, legal advisor to the Aldermen in their capacity as Justices to the City, and also to the Commissioner of Police. He is the City Public Prosecutor, and, apart from the recorder and Common Sergeant, is necessarily the active legal luminary in the Corporation.’4 In short, ‘the active legal luminary’ was no dope. Co-author of A Statement of the Origin, Constitution, Powers and Privileges of the Corporation of London, he knew his City business, and was one day to become its Lord Mayor. Although he began by seeking Langham’s consent to ask the occasional question, Crawford ended up asking almost all of them.

The proceedings at Golden Lane opened with the usual civilities, and a dispiriting traipse through those who had seen little – and most of them less than that. The coppers (and the nightwatchman) who had discovered Eddowes’ still-warm body came in and read from their notebooks. The jury heard from Inspector Collard and City Architect Frederick Foster, who had made drawings of the crime scene and drawn up a plan. Without depriving the narrative of substance, all can be dispensed with until we get to the deposition of Dr Gordon Brown. Brown’s contribution is replete with medical jargon, and is too long to reproduce in full here. I therefore use the version reported in The Times, supplementing the text from the original where necessary. ‘Frederick Gordon Brown, 17 Finsbury Circus, Surgeon of City of London Police, being sworn saith’:

I was called shortly after 2 o’clock. I reached [the Square] about 18 minutes past 2 my attention was called to the body of the Deceased … The body was on its back – the head turned to the left shoulder – the arms by the side of the body as if they had fallen there, both palms upwards – the fingers slightly bent, a thimble was lying off the finger on the right side. The clothes were drawn up above the abdomen, the thighs were naked, left leg extended in line with the body. There was great disfigurement of the face. The throat was cut across to the extent of 6 or 7 inches. The abdomen was all exposed. The intestines were drawn out to a large extent and placed over the right shoulder – they were smeared with some feculent matter. A piece of about two feet was quite detached from the body and placed between the body and the left arm, apparently by design.

Crawford’s question vis à vis ‘design’ has been quoted on a previous page. Dr Brown’s statement continued: ‘… The lobe and auricle of the right ear [my emphasis] were cut obliquely through; there was a quantity of clotted blood on the pavement, on the left side of the neck and upper part of the arm … The body was quite warm (no rigor mortis) and had only been there for a few minutes.’ ‘Before they removed the body’, he ‘suggested that Dr Phillips should be sent for, and that gentleman, who had seen some recent cases, came to the mortuary … Several buttons were found in the clotted blood after the body was removed … There was no blood on the front of the clothes. There were no traces of recent connection [i.e. no sponk]. When the body arrived at Golden Lane the clothes were taken off carefully from the body, a piece of the deceased’s ear dropped from the clothing.’5

This will prove of significance. Dr Brown had noticed at the crime scene that ‘the lobe and auricle of the right ear were cut obliquely through’ (i.e. the whole ear), but only a part of the ear, the lobe, was discovered on arrival at the mortuary. Where the auricle went, whether it was retrieved or had been taken away by the murderer, is not disclosed.

Brown then goes on to describe a truly astonishing catalogue of injuries. The assassin had ripped through Eddowes as if he was on his way to somewhere else: ‘The womb was cut through horizontally leaving a stump 3/4 of an inch, the rest of the womb had been taken away with some of the ligaments … the peritoneal lining [the internal surface of the abdomen] was cut through on the left side and the left kidney taken out and removed.’ (My emphasis.)

Crawford asks if the stolen organs could be used for any professional purpose. Brown’s answer was in the negative: ‘I cannot assign any reason for these parts being taken away.’ Crawford then asks: ‘About how long do you think it would take to inflict all these wounds, and perpetrate such a deed?’ The physician reckoned about five minutes, and confirmed his opinion that it was the work of one man only. He was then asked ‘as a professional man’ to account for the fact of no noise being heard by those in the immediate neighbourhood.

BROWN: The throat would be so instantaneously severed that I do not suppose there would be any time for the least sound being emitted.

CRAWFORD: Would you expect to find much blood on the person who inflicted the wounds?

No. He would not. But he could confirm that bloodspots on Eddowes’ apron (which was produced) were recent.

Crawford asked: ‘Have you formed any opinion as to the purpose for which the face was mutilated?’ This is an interesting question. Crawford suggests that the face may have been mutilated for a purpose. The doctor had no opinion, thinking it was ‘simply to disfigure the corpse’. He added that a sharp knife was used, ‘not much force required’.

If anyone on the jury had any questions about those inverted ‘V’ marks on Eddowes’ face, they were out of luck, because Coroner Langham here adjourned, reconvening the court one week hence.

The next few days gave Crawford time to reflect, perhaps even to dwell on the ‘purpose’ of the curious mutilations, and what they might mean in concert with the ritualistic mutilations of Annie Chapman. Crawford must have been as cynical as everyone else about the fabulous adventures of ‘the American Womb-Collector’, particularly when a doctor had just told him that the burgled organs would be useless for medical purposes.

So why would the coroner at Annie Chapman’s inquest, Baxter, countenance such hogwash? Was it in any way connected with Warren’s destruction of the writing on the wall? Was there some undisclosed reason for wanting it rubbed out? These were questions to ponder, albeit with answers which Crawford had already determined.

On Thursday, 11 October, The Times reported on the resumption of the inquest, claiming that a ‘good deal of fresh evidence’ was on the cards. ‘Since the adjournment,’ it continued, ‘Shelton, the Coroner’s Officer, has, with the assistance of City Police authorities, discovered several new witnesses.’ These included a couple of (briefly suspected) male associates of Eddowes, and even her long-lost daughter. No one paid much attention to this crew, and neither do I. But there were some new witnesses of interest.

At about 1.30 a.m. on the night of Eddowes’ murder, three gents left their club in Duke Street, and stepped out into the rain. The Imperial Club was an artisans’ night out, exclusively Jewish, catering to the upper echelons of the working class. Two of the men walked slightly in advance of the third. They were Joseph Levy, a butcher, resident just south of Aldgate, and Henry Harris, a furniture dealer of Castle Street, Whitechapel.

Mr Harris wasn’t called to give evidence at the inquest, because he said he saw nothing, and that his companions saw nothing either, ‘just the back of the man’. But one of them clearly did see something. He was a forty-one-year-old commercial traveller in the cigarette trade, by the name of Joseph Lawende.

Lawende had already attracted press attention. On 9 October, two days before the resumption of the inquest, the Evening News had published a summary of what the public might expect in respect of this trio’s exit from the Imperial Club: ‘They noticed a couple – a man and woman – standing by the iron post of the small passage that leads to Mitre Square. They have no doubt themselves that this was the murdered woman and her murderer. And on the first blush of it the fact is borne out by the police having taken exclusive care of Mr Joseph Lawende, to a certain extent having sequestrated him and having imposed a pledge on him of secrecy. They are paying all his expenses, and 1 if not 2 detectives are taking him about.’

It’s assumed by The Jack the Ripper A to Z that the City Police were protecting Lawende from the press. This may be so, but it’s obvious that they were also protecting him from the Met. They didn’t want anyone making – shall we say – unhelpful suggestions about what he may or may not have seen. This is corroborated by a Home Office minute later in the month. With quite startling hypocrisy, it states: ‘The City Police are wholly at fault as regards detection of the murderer. They evidently want to tell us nothing.’6

If I were the City Police – most particularly over the farce at Goulston Street – I wouldn’t want to tell the Home Office anything either. It’s clear, in respect of wash-it-off-Warren, that the City Police were attempting to protect the integrity of their witness.

Two days later, Levy and Lawende were in court. But this time there was an adjustment in approach from the ‘active legal luminary’. Crawford knew perfectly well why Warren had washed off that wall. He also knew about the article in the Evening News, and was about to prove it correct.

It had been pouring with rain on the night of the murders, and Joseph Levy told the court ‘he thought the spot was very badly lighted’, and that his ‘suspicions were not aroused by the two persons’: ‘He noticed a man and a woman standing together at the corner of Church Passage, but he passed on without taking any further notice of them. He did not look at them. From what he saw, the man might have been three inches taller than the woman. He could not give a description of either of them … he did not take much notice.’

What are we to make of so vacuous a deposition? It was what novelists call a filthy night in a poorly lit alleyway. Levy had a brim-down glimpse of a man and a woman. ‘From what he saw, the man might have been three inches taller’. Eddowes was a diminutive five feet, meaning her paramour ‘might’ have been five feet three inches. However, if he was a taller man, he ‘might’ have been leaning down to whisper sweet nothings in her ear. We cannot know, and certainly not from Levy, because ‘He did not look at them.’

Peripheral estimates such as his are worthless. An on-site witness, Abraham Heshburg, who actually saw Elizabeth Stride as she lay dead at Dutfield’s Yard, estimated her age as twenty-five to twenty-eight – she was forty-four, and Heshburg was about twenty years out.7 Predicated on the enormous variations of physical description, we can assume that the Ripper was between five and six feet tall, and between thirty and fifty years old – like virtually half the male population of London. It is only when a description is specific that it begins to have some worth, and this perhaps explains why Levy was not under police escort.

We now come to the man who was.

JOSEPH LAWENDE 45 Norfolk Road, being sworn saith:– On the night of the 29th I was at the Imperial Club. Mr Joseph Levy and Mr Harry Harris were with me. It was raining. We left there to go out at half past one and we left the house about five minutes later. I walked a little further from the others. Standing in the corner of Church Passage in Duke Street, which leads into Mitre Square, I saw a woman. She was standing with her face towards a man. I only saw her back. She had her hand on his chest. The man was taller than she was. She had a black jacket and a black bonnet. I have seen the articles which it is stated belonged to her at the police station. My belief is they were the same clothes which I had seen upon the Deceased. She appeared to me short. The man had a cloth cap on with a cloth peak. I have given a description of the man to the police.

But he isn’t giving it here, where only the man’s hat is described. ‘The man was taller than she was … She appeared to me short.’ Did she appear short because the man was much taller than her? It’s a question I would like to have asked, but Coroner Langham asked the question instead: ‘Can you tell us what sort of man it was with whom she was speaking?’

Lawende had clearly been warned off, and again described the man’s hat: ‘He had on a cloth cap with a peak.’ The jury had already heard that, and just in case anyone was looking for a little more description than a hat, Crawford interceded:

Unless the Jury wish it I have a special reason [my emphasis] why no further description on this man should be given now.

The City Police had been protecting Lawende, and now they shut him up. The jury ‘assented to Mr Crawford’s wish’, although I don’t imagine they realised it would be sustained for the next 130 years. Here was a witness who had information about the killer – height, age, whatever – under the ‘exclusive care’ of the City Police, who had imposed ‘a pledge of secrecy’.

Crawford had just defended the pledge, adding veracity to the Evening News report. Here was a man who, at a minimum, had had a glimpse of Jack the Ripper, yet his description was suppressed, and remains a secret to this day.

Cue the fairy dust.

On page 247 of his book, Mr Philip Sugden makes a convoluted and unsuccessful effort to explain away the description Crawford wanted kept secret. He would like us to believe that it is no secret at all, but was brought into the open by the Metropolitan Police on 19 October 1888. He refers us to a description in the Met’s own weekly newspaper, the Police Gazette. The Gazette was founded by Howard Vincent in 1884, and was brought into disrepute by Warren and his boys with the kind of casuistry proffered by Mr Sugden.

‘Lawende saw the man too,’ he writes energetically, ‘but the official transcript of his inquest deposition records only that he was taller than the woman and wore a cloth cap with a cloth peak. Press versions of the testimony, however, add the detail that “the man looked rather rough and shabby”, and reveal that the full description was suppressed at the request of Henry Crawford, the City Solicitor, who was attending the hearing on behalf of the [City] Police. Fortunately,’ he enthuses, ‘this deficiency in the record can be addressed from other sources. Lawende’s description of the man was fully published in the Police Gazette of October 19th 1888.’8

To which I add the word ‘Bollocks.’

Here is Mr Sugden’s historic breakthrough, as published in the Police Gazette on 19 October 1888: ‘… a MAN, aged 30, height 5ft 7 or 8 in., complexion fair, moustache fair, medium build, dress, pepper and salt colour loose jacket, grey cloth cap with peak of same material, reddish neckerchief tied in a knot; appearance of a sailor’. This description of 19 October, grasped by Mr Sugden, was in fact published in The Times on 2 October, more than a week before Lawende gave his evidence, and more than two weeks before its appearance in the Police Gazette. It therefore can have absolutely nothing whatever to do with the description Crawford suppressed at the inquest.

This is what The Times printed on 2 October: ‘… the man was observed in a court in Duke Street, leading to Mitre Square, about 1.40 a.m. on Sunday. He is described as of shabby appearance. About 30 years of age and 5ft 9in in height, of fair complexion, having a small fair moustache, and wearing a red neckerchief and a cap with a peak.’

Apart from knocking a useful inch or two off the height and adding a bit of nautical gibberish, the Police Gazette/Times descriptions are as near as makes no difference, red neckerchief and all. Thus Mr Sugden’s supposed revelation is no such thing, and certainly has nothing to do with the description Crawford suppressed.

I am aware of The Times’s description 130 years after it appeared. Are we to imagine that a man as sharp as Henry Crawford was ignorant of something published in The Times only nine days before? Crawford was a man of rare intellect, and it is simply ridiculous to imagine that he would try to suppress something that had recently been printed in 40,000 copies of the world’s most prestigious newspaper. Crawford would have to be as foolish as Sugden to suggest it. And the Evening News, despite The Times piece a week before, was very well aware on 9 October that the City Police were keeping something secret.

Unless Mr Sugden thinks a ‘pepper and salt’-coloured jacket glimpsed in darkness and rain is some kind of dramatic breakthrough, the Police Gazette has elucidated absolutely nothing. Sugden describes this grey jacket as ‘a fortunate addition to the deficiency of the record’. I call it worthless twaddle. This belated confection in the Police Gazette doesn’t explain Crawford’s imposition of secrecy, and has no value. It is simply a cooked-up, out-of-date newspaper reprint, another dispatch from the Land of Make Believe. If this description had any validity to the Metropolitan Police on 2 October, why not print it in the Police Gazette on that day? Or the 5th? Or the 9th? Or the 12th? Or the 16th? Why wait for the issue of 19 October?

The real reason the Met regurgitated this unsourced ‘description’ was to coincide with an internal report Bro Inspector Donald Swanson had prepared on the same date. Destined for the Home Office, this concoction of 19 October makes reference to the man with the red neckerchief, and since they’d never bothered with him before, it would look most untoward it they didn’t fabricate some interest now. Hence, seventeen days after his appearance in The Times ‘the Seafaring Man’ makes his debut in the Police Gazette, only to be dismissed on the very same day by Swanson himself. ‘I understand from the City Police,’ he wrote, ‘that Mr Lewin [sic] one of the men who identified the clothes only of the murdered woman Eddowes, which is a serious drawback to the value of the description of the man’ (which, incidentally, Lawende never publicly made).9

So despite a front page of the Met’s house journal, even Swanson thinks he’s got nothing on Jack, and only a description of Eddowes’ clothes. Crawford would have had to have been some kind of full-blown half-wit to want to conceal that.

Bye bye, sailor.

The problem with Mr Sugden is that he is all wallpaper and no wall. I sincerely have no desire to isolate him for criticism, but at every point of contention he’s there with his paste-pot and paper. It’s so frequent (not only from him, but from Ripperology in general) that it reads like a kind of corporate hypnotism.

But this description of the man with the ‘reddish’ neckerchief raises some questions. To have been published on 2 October, it must have been known to The Times on the 1st. Where did it get the information? Harris said he saw nothing. Levy said he saw nothing either. He therefore didn’t see a thirty-year-old, five-foot-nine-inch man with a fair moustache and a red neckerchief tied in a knot. Two of these three witnesses are thus dismissed as sources, and what Lawende saw was withheld ever after.

I think this nautical geezer with the red neckerchief is in the tradition of Metropolitan Police inventions (riots in Goulston Street, etc.), slipped by an unknown source to The Times. By this time the Met were under catastrophic pressure, and Warren was less than forty days from the exit. Swanson’s ‘report’ from Scotland Yard was three parts panic, and the rest distortion to fit the fiction Warren was committed to tell. We will never know from whence the seafarer and his neckerchief came, any more than we can know what description Crawford suppressed.

But I don’t like half-arsed ‘mysteries’, and though I might never be able to find out what Crawford withheld, I thought there was a better-than-odds-on chance of discovering why he withheld it. I got a red light about Crawford, and I think it was precisely the same red light he had about ‘Juwes’ and Jack.

If there really was a ‘special reason’ for stifling Lawende’s description, why was it not later revealed? Was it, in the short term, an effort to keep it secret from the Met? After the shenanigans at Goulston Street, it’s possible. Commissioner Smith never forgave Warren, calling his erasure of the writing on the wall ‘an unpardonable error’. Maybe he was determined to keep the slippery bastard out. But I was persuaded that there was a more complex dynamic to be discovered.

Immediately following Levy/Lawende, PC Long was the next witness to be called – a patsy put up to try to divert attention from the duplicity of the men who didn’t care to show themselves.

Long was the only representative of the Metropolitan Police to appear before the court. Neither Arnold nor Warren was called – the latter, according to the Pall Mall Gazette, because the court didn’t want to hold him to contempt. But contempt over what? It wasn’t yet widely known that London’s Commissioner of Police had colluded to conceal the identity of London’s most wanted killer. On 11 October the Evening News ran a report commenting on the court proceedings.

The words ‘The Jews are not the men who will be blamed for nothing,’ were almost certainly written by the murderer, who left at the spot the bloody portion of the woman’s apron as a sort of warranty of authenticity. On Police Constable Long’s report consultation was held and the decision taken to rub out the words [emphasis in the original]. Detective Halse of the City Police protested. A brother officer had gone to make arrangements to have the words photographed, but the zeal of the Metropolitans could not rest. They fear a riot against the Jews and out the words must come. And the only clue [my emphasis] to the murderer was destroyed calmly and deliberately, on the authority of those in high places.

Attempts to navigate the Juwes/apron débâcle were still high on the agenda of Warren’s hidden anti-detective work. On 3 October he had written to his City counterpart, Commissioner Colonel Sir James Frazer, attempting to solicit his blessing for a grab at the surreal. The ‘riot’ angle clearly lacked traction, so to accompany ‘the Nautical Man’ and ‘the Womb-Collector’ he conjured up the limpest suspect yet, ‘the Goulston Street Hoaxer’.

In a rambling text, Warren asks Frazer ‘If there is any proof that at the time the corpse was found the bib [sic] was found with the piece wanting that the piece was not lying about the yard [sic] at the time the corpse was found and taken to Goulston St by some of the lookers on as a hoax & that the piece found in Goulston St is without doubt, a portion of that which p’y was worn by the woman.’10

Never mind conflating Dutfield’s Yard with Mitre Square, implicit in this letter is Warren’s utter worthlessness as a common policeman, much less Commander in Chief of Scotland Yard.

Even though it was in ignorance of his letter to Frazer, the Evening News agreed. ‘We cannot blame the inferior police,’ it wrote (referencing one such constable, who now stood in front of Crawford), ‘but the public have a right to know who gave the order to efface the murderer’s traces. His proper place is not in the Criminal Enquiry department.’11

It was within Coroner Langham’s powers to insist that both Warren and Dr Phillips attend his court, but he didn’t insist, and they didn’t attend, although Phillips was actually scheduled to appear, and his name is on the witness list.

Maybe he had a head cold on the day in question? But that can’t be, because he was concurrently dissembling at the Elizabeth Stride inquest. Had he shown up, Crawford’s line of questioning would of necessity have had to include the discovery of the apron, and a timeline à propos of it. Long handed the apron to Phillips at five or ten minutes past 3 a.m. By 3.30 at the latest it was in the possession of Dr Brown (and Thomas Catling) at the Golden Lane morgue.

3.30 a.m. is a time to remember.

Meanwhile, Crawford had nobody to question about the provenance of the portion of Mrs Eddowes’ apron but the hapless Police Constable Alfred Long.

CRAWFORD: Had you been past that spot previous to your discovering the apron?

LONG: I passed it about 20 minutes past two o’clock.

And was it there then? No, it was not. Crawford had simply listened to the evidence from everybody else, but was actually interrogating PC Long.

CRAWFORD: As to the writing on the wall, have you not put ‘not’ in the wrong place? Were not the words ‘The Jews are not the men that will be blamed for nothing’?

LONG: I believe the words were as I stated.

CRAWFORD: How do you spell ‘Jews’?

LONG: J-E-W-S.

CRAWFORD: Now, was it not on the wall J-U-W-E-S? Is it not possible you are wrong?

LONG: It may be as to the spelling.

CRAWFORD: Why did you not tell us that in the first place? Did you make an entry of the words at the time?

LONG: Yes, in my pocket book.

CRAWFORD: As to the place where the word ‘not’ was put? Is it possible you have put the ‘not’ in the wrong place?

According to The Times, ‘Witness again read the words as before,’ although we are not told what he read them from. Whatever it was, it wasn’t satisfactory to the jury, its foreman making the point.

FOREMAN: Where is the pocket book in which you made the entry of the writing?

LONG: At Westminster.

FOREMAN: Is it possible to get it at once?

Crawford then asked Langham to direct that the book be fetched, and Long was sent scuttling to Westminster to get it.

I don’t imagine he’d forgotten his notebook by accident. A copper called to give information at an enquiry into a murder will have his book with him. But Long hadn’t thought to bring it.

No such deficiency was attendant on City Detective Halse, who was next to face Crawford’s questions. The solicitor covered the same ground as he had with Long, and everything was pretty much in sync until it came to the discovery of the writing on the wall.

HALSE: At 20 minutes past two o’clock I passed over the spot where the piece of apron was found, but I did not notice anything then. I should not necessarily have seen the piece of apron, because it was in the hall.

Halse’s deposition is in direct conflict with Warren’s. In order to enhance the apron’s incendiary credentials, Warren moved both it and the writing as near to the street as fiction would allow. In his 6 November concoction he wrote: ‘The writing was on the jamb of the open archway or doorway visible to anybody in the street.’ Except, apparently, at 2.20 a.m., when Long and Halse passed by. They stated respectively that the apron ‘was lying in a passage leading to the staircases’, and ‘the writing was in the passage of the building itself’. It’s noticeable that nowhere in this entire hearing is the name Warren mentioned, and of further note that henceforth Crawford spells the crucial word Jews as ‘Juwes’.

CRAWFORD: Did anyone suggest that it would be possible to take out the word ‘Juwes’ and leave the rest of the writing there?

HALSE: I suggested that the top line might be rubbed out, and the Metropolitan Police suggested the word ‘Juwes’.

It would seem that at least someone in the Met wanted to preserve the writing for the photographer – but he wasn’t the same member of the Metropolitan Police who wanted it rubbed out.

CRAWFORD: Read out the exact words you took in your book at the time.

HALSE: ‘The Juwes are not the men that will be blamed for nothing.’

CRAWFORD: Did the writing have the appearance of being recently done?

HALSE: Yes. It was written with white chalk on a black facia.

Not ‘blurred’, not ‘rubbed’, not ‘old’, as Mr Sugden might wish it. But here comes the killer question that Warren, and not a few of his apologists, might wish had never been asked.

FOREMAN: Why was the writing really rubbed out?12

Bang goes the twaddle about ‘riot’ – this member of the jury simply didn’t believe it. Not a ridiculous word of it. Why the writing was really rubbed out was precisely the point Crawford was trying to establish. Keeping his own counsel, the cautious solicitor allowed Detective Halse to answer the foreman’s question.

HALSE: The Metropolitan Police said it might cause a riot and it was on their ground.

It isn’t recorded whether the foreman thought he’d had a satisfactory answer, but to judge from the ensuing furore in the press, it would seem that he had not. Why this writing was really rubbed out has defined the life-blood of Bro Jack and the circus of smokescreens and moving mirrors ever since.

From the moment of its discovery there was an intense effort on the part of the Metropolitan Police to withhold, obfuscate, misrepresent, obscure and destroy any link between the writing on the wall and the butchery in Mitre Square. Nothing could be more important than this nexus, what the Evening News accurately described as ‘a warrant of authenticity’.

Such a warrant should surely have been the starting point of the subsequent investigation. Instead, like Laurel and Hardy in bizarre harmony with Freemasonry, the intention of Ripperology has been not to explore it, but, like Warren, to get rid of it. The initiative of the City Police is marginalised in favour of supporting the lunacy of Warren and his preposterous ‘riot’. The writing must be diminished into some kind of nonsensical ‘graffito’ that supposedly no one can understand. Well, Crawford understood it, and with the return of Constable Long, he was about to have his understanding confirmed.

The immediate question to be answered from Long’s retrieved notebook was the entry he made at the time concerning discovery of the writing on the wall.

CRAWFORD: What is the entry?

LONG: The words are, ‘The Jeuws are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.’

Contradicting Halse, he spells Jews ‘J-E-U-W-S’. Not good enough for Crawford, who referred him to an inspector’s report. Since this report was never written into the record, we don’t know who this inspector was. Was it the inspector PC Long brought hurrying from Commercial Road, or was it another report from another inspector?

CRAWFORD: Both here [in the notebook] and in your Inspector’s report, the word ‘Jews’ is spelled correctly?

LONG: Yes, but the Inspector remarked that the word was spelled ‘J-U-W-E-S’.

CRAWFORD: Why did you write ‘Jews’ then?

LONG: I made the entry before the Inspector made the remark.

CRAWFORD: Why did the Inspector write ‘Jews’?

Long couldn’t say; but Halse could, and Crawford chose the unequivocal spelling out of his more properly available notebook. It all would have been so much easier if the jury could have relied on photographic evidence. Be that as it may, the spelling confirmed in this court was ‘J-U-W-E-S’, and never mind what ‘respectable historians’ later tried to make of it.

Although the jury may not have understood why, it’s incontestable that the particularity of this spelling was of considerable importance to Crawford, albeit without the remotest interest in ill-fitting footwear or the distractions of anti-Semitic rioting.

He wasn’t investigating a potential riot, he was investigating an actual murder, and as was later pointed out, ‘Crawford was trying to prove something, and not that the Ripper was bad at spelling.’13

So what was this urbane and highly competent solicitor up to? What could he see in the spelling of ‘Juwes’ that Bro Charlie Warren apparently could not? And what was the difference for Crawford between ‘The Jews are not the men that will be blamed for nothing’ and ‘The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing’? Crawford was after accuracy because the two sentences mean starkly different things. The first may be interpreted as anti-Semitic, blaming a general race of men called Jews; the second narrows it down to a more specific group, blaming a particular type of man the Ripper elected to spell as ‘Juwes’.

Ripperologist Mr Paul Begg makes a point that misses the point as he makes it: ‘The erasure did not prevent the spelling of the word becoming known,’ he writes. ‘Moreover, even if the writing had been left, who – other than senior Masons – would have known the significance of the word, and would senior Masons have been any less anxious than Warren to keep the Masonic connection unrevealed?’14

No, they would not. Masons keep their mouths shut, so Mr Begg’s point is irrelevant. I’m not sure if he’s here acknowledging that only ‘senior Masons would have known the significance of the word’. If he is, I am in agreement, because the Commissioner of London’s police was a senior Mason.

But the conundrum – public or not – of ‘Juwes’ is not actually the point at issue. Of course its significance was apparent to anyone acquainted with Freemasonic ritual: examples of whom are Bro Jack the Ripper, Bro Sir Charles Warren, and City Solicitor Bro Henry Homewood Crawford.

Crawford knew what ‘Juwes’ meant, because he was a Mason, and what with the rest of it, he put it together just as fast as Warren had before he got out of bed. Crawford had confirmed what he already knew, and was now in the loop himself. A sentinel of the Establishment, and virulently conservative, he had taken the same oath as Warren, and was no less a subject of the Mystic Tie. Having done its business in Bro Baxter’s court, the ‘Mystic Miasma’ now relocates its hypnotic vapours to Langham’s.

Their effects are immediate, and as wondrous as anything achieved by any fairy godmother. Extraordinary as it is to behold, Crawford now begins a process of obfuscation himself, shifting his allegiance away from the jury and towards the Met. His tone respecting PC Long changes from accusatory to conciliatory; from now on Bro Crawford becomes no less defensive of the shenanigans at Goulston Street than Bro Sir Charles Warren himself.

JUROR: It seems strange that a police constable should have found this piece of apron and then for no enquiries to have been made in the building? There is a clue up to that point and then it is altogether lost?

Switching the substance of the question away from the Met, Bro Crawford answers one about the City that was never asked:

CRAWFORD: I have evidence that the City Police did make a careful search in the tenement, but it was not until after the fact had come to their knowledge. But unfortunately it did not come to their knowledge until two hours after. I’m afraid that will not meet the point raised by you [the juror]. There is the delay that took place. The man who found the piece of apron is a member of the Metropolitan Police.

JUROR: It is the man belonging to the Metropolitan Police that I’m complaining of.

Ignoring this criticism of the Met, Crawford again deflects to the City Police, investing them with a totally phoney timeframe: ‘Unfortunately,’ he said, ‘it did not come to their knowledge until two hours later.’

Not to put too fine a point on it, this is a lie. City Inspector McWilliam ordered photographs at 3.45 a.m., and ‘directed the officers to return at once to the model dwellings’. But Crawford would now have the jury believe that two hours had elapsed, meaning the City Police didn’t get to Goulston Street until 5.45 a.m., forty-five minutes after Warren had pitched up there.

Given what the jury had already heard, Crawford’s explanation is untenable, and as the juror was well aware, a search of the building was technically nothing to do with the City. Goulston Street was in Warren’s manor, and such a search was the responsibility of the Met. That they didn’t search the building was the reason the juror thought the clue ‘altogether lost’.

Indifferent to such trivialities, Crawford put a couple of already answered questions to Long before making the two-hour time leap himself. What time did Long leave Leman Street police station and return to the wall?

LONG: About five o’clock.

CRAWFORD: Had the writing been rubbed out then?

LONG: No, it was rubbed out in my presence at half past five.

CRAWFORD: Did you hear any one object to its being rubbed out?

LONG: No.

And Crawford lets him get away with it. He seems to have entirely forgotten the protest from City Detective Halse, amongst others, and the divisional friction over the preservation of this evidence that extended for half an hour (the half-hour Long says he was there). If Halse was still in court he must have thought Crawford had gone nuts – but then, he was unaware that this most excellent solicitor was subservient to a higher authority than a coroner’s court.

Bro Crawford had all but come to the end of his questions, and Langham was about to pay the traditional valediction to some person or persons unknown.

Coroner Langham’s closing speech is remarkable, paying not the slightest attention to any of the evidence his court had heard. In the spirit of Victorian orthodoxy, his summing-up ignored everything that didn’t suit the predetermined outcome. Observing that ‘the evidence had been of a most exhausting character’, he totally disregarded it. ‘It would be far better now,’ said the rented mouth, ‘to leave the matter in the hands of the police, to follow up with any clues they might obtain.’

Which brings us back to precisely where this charade started: with the Metropolitan Police. One can only blink at the peripheries of Wonderland at what ‘clues’ he had in mind. The verbiage he’d just ejaculated made no mention of a single clue the police already had. To summarise the summing-up: both ‘suspects’ (a couple of irrelevances who had formerly been associated with Eddowes, called Thomas Conway and John Kelly) had been eliminated, one of them proving to have been asleep at the time of the crime. It was also established that a day or two before her murder Eddowes had gone to Bermondsey, in South London, looking for her daughter. ‘Something might turn on the fact that she did not see her,’ announced the mouth, ‘but the daughter had left the address there without mentioning any other address to which she was going’ (Langham neglected to mention that this address was two years old, and that Eddowes hadn’t seen her daughter since 1886).

While the jury absorbed the implications of these forensic exactitudes, Langham came to his point. ‘There could be no doubt,’ he intoned, ‘that a vile murder had been committed.’ And doubtless grateful for the mention of it, the jury was dismissed.

This most eminent pie-baker declined to remind them of any evidence that might apply itself to the identity of the murderer. Where did he go during the missing forty-odd minutes between Mitre Square and Goulston Street? If the purpose of the severed apron was only to wipe his hands, why transport it over so great a distance? Was it really to try to blame the Jews (he could have blamed the Jews just as easily at Mitre Square), or for some other reason? Neither Jews nor riot appear to have had any relevance for Langham, and not an iota of comment is given on either. He declines even to consider the altercation over photographing the writing on the wall – as a matter of fact, he makes no mention of the writing at all. PC Long’s round trip to Westminster passes unremarked, as does the confirmation of the much-contested spelling of ‘Juwes’. The unanswered question over why the writing was ‘really rubbed out’ is of no concern, which probably explains why the piece of apron that came with it had entirely slipped Langham’s mind. Although such evidence could have hanged the Ripper, both it and its relationship with the murderer had vanished into thin air. Langham had quite forgotten it, making no mention of the apron, nor of the events preceding or following its discovery. PC Long’s beeline to Leman Street and his inexplicable languor on arrival there were no concern of this court.

Neither, apparently, were missing body parts. Was not Langham of a mind to remind the jury of them? Repudiating the comic gibberish regarding ‘the Womb-Collector’, Dr Gordon Brown determined that the stolen organs would have no professional utility. So for what reason were they taken? And what should be made of it if any of these organs (a kidney, for example) should be discovered, or in some way reappear?

A multitude of unanswered questions left the jury in a vacuum. What did ‘Juwes’ actually mean, and why was its precise spelling of such importance to Crawford? Why didn’t the Metropolitan Police search the model dwellings at Goulston Street – and where indeed were the Met’s senior detectives? Why were no photographs taken of the writing on the wall, why was it ‘really rubbed out’, and what kind of idiot could have demanded it? And lastly, who or what was Crawford concealing when he suppressed Joseph Lawende’s description of Jack the Ripper?

It remained only for Langham to ‘thank Mr Crawford’ on the jury’s behalf, ‘and the police for the assistance they had rendered the enquiry’.

Gratitude extended well beyond Langham’s little emporium. It was felt in the highest echelons of Scotland Yard, and in the apartment of a gentleman psychopath living in London NW.

The Ripper had made another convert, adjusting Crawford’s integrity to the level required. Just as Coroner Wynne Baxter had been subject to its gravity over Annie Chapman, so now had Crawford with a jury of his own to deceive. We are heading into a phenomenon that will reiterate itself with escalating duplicity in proportion to Establishment panic. At Chapman’s inquest, a Freemason suppressed evidence. At Goulston Street, a Freemason suppressed evidence. At Eddowes’ inquest, a Freemason suppressed evidence, including a description of the murderer himself.

The Victorian authorities knew perfectly well that they were looking for a Freemason (or rather, that they were protecting one). But they didn’t yet know who he was.

We shall never know what Joseph Lawende saw. Notwithstanding that, anyone scratching around Crawford and his ‘secret’ will discover some fascinating ancillary information.

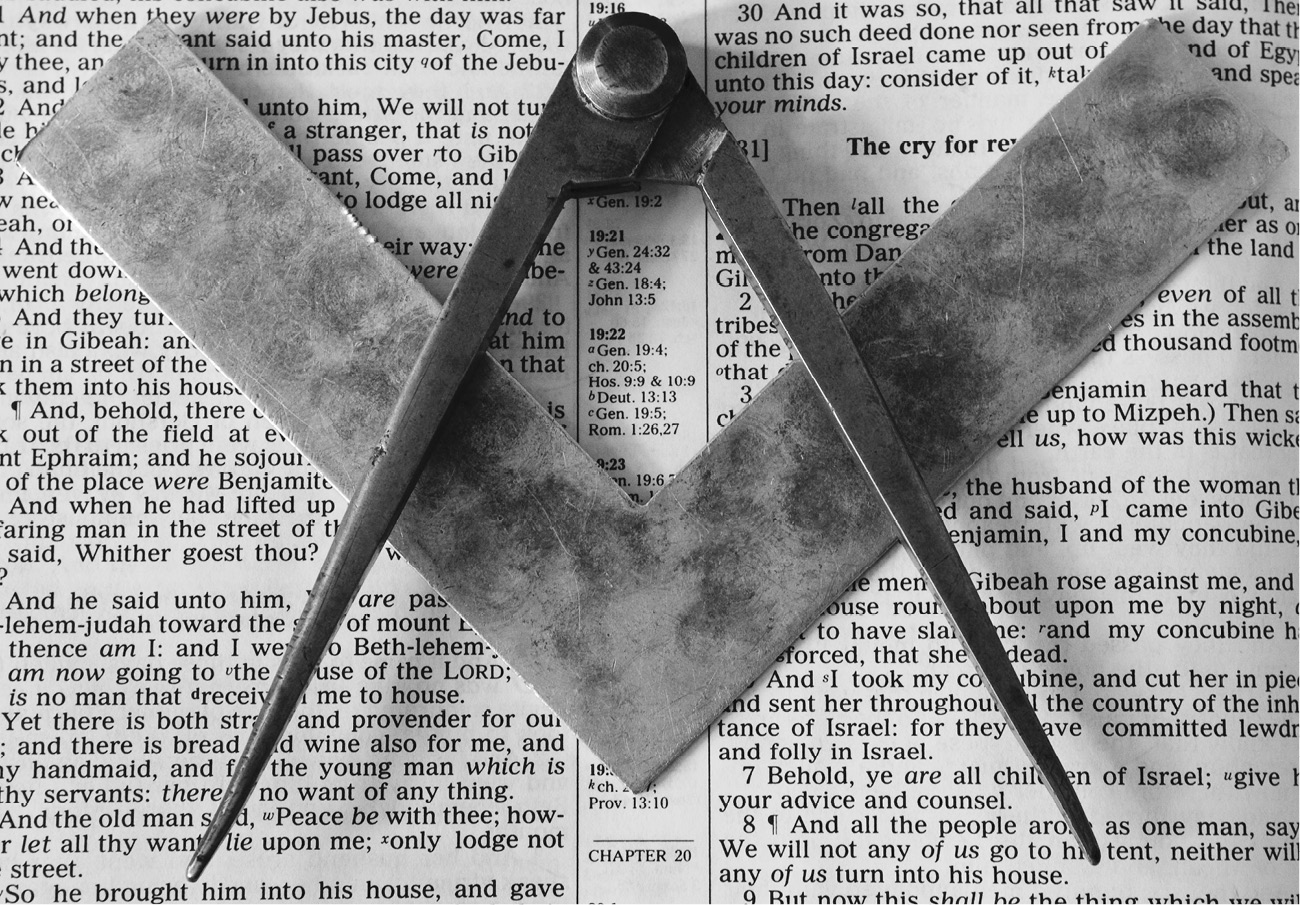

If not quite in the exalted league of Sir Charles Warren, Bro Henry Homewood Crawford was nevertheless well situated in the Masonic hierarchy. Founder of the Guildhall Lodge (3116), Past Master in Grand Master’s Lodge (No 1), and elevated into the Royal Arch in the same Chapter, in the spring of 1889 Crawford was appointed Grand Steward of the United Grand Lodge, and found himself among some distinguished company. It was a big day, followed by a big banquet, ‘most beautifully served’. A report of the proceedings can be found in the Freemason’s Chronicle:15

The festival, which is held, according to ancient custom, on the Wednesday next St. George’s Day, was preceded by a meeting of Grand Lodge, to which rulers of the Craft only were admitted [my emphasis]. The minutes respecting the Prince of Wales as Grand Master at the last Grand Lodge having been confirmed, Sir Albert Woods [Garter] King-at-Arms, proclaimed His Royal Highness, according to ancient form. The mandate of Grand Master was then read, reappointing the Earl of Carnarvon Pro Grand Master, and the Earl of Lathom as Deputy Grand Master. The other officers were invested as follows:

Henry Homewood Crawford was elected as a Grand Steward on the day my candidate was elected as Grand Organist. Once again, I make no sinister imputation towards members of this assembly who hadn’t the remotest idea of the assassin in their midst. But this is a yet further example of how Michael Maybrick was embedded in the Brotherhood he despised and was betraying.

At this august event, the fraternal associate of James and Michael Maybrick, Bro the Earl of Lathom, was reappointed as Deputy Grand Master. One or two of the names represented become faces in the engraving opposite. Celebrating Her Majesty’s fifty years of rule at her Jubilee in 1887, this montage displays the apogee of Masonic authority together with its indivisible association with the Crown. The woman in the picture wasn’t a Freemason, but in regal quid pro quo, Freemasonry couldn’t have existed without her. Her Majesty aside, at least three of these men are close associates, if not intimates, of Michael Maybrick: Woods, Lathom and Colonel Shadwell Clerke.

But let us stay with the list of revered ‘rulers’, not a few of whom were of no little importance in the Victorian hierarchy: Senior Warden Lord George Hamilton (First Lord of the Admiralty in Salisbury’s Cabinet); Junior Warden Sir John Eldon Gorst, MP for Chatham (Under Secretary for India 1886–91, Financial Secretary to the Treasury 1891–92, and ofttimes a resident at Toynbee Hall, the ‘university for the poor’ in London’s East End); Chaplain the Honourable and Reverend Francis Byng (Chaplain to Her Majesty Queen Victoria 1865–89); Senior Deacon Sir Polydore de Keyser (Crawford’s boss and Lord Mayor of London during the Ripper crisis, serving until 9 November 1888); Superintendent of Works Colonel Robert Edis (a leading light in ‘Mark Masonry’, close to Edward, Prince of Wales, as he was to Michael Maybrick, commanding officer of the 20th Middlesex Rifles, ‘the Artists Volunteers’, whose Honorary Colonel was one of Prince Edward’s closest personal friends, Sir Frederick Leighton, an unlikely overlord of a battalion we shall be hearing more of, and to which Captain Michael Maybrick belonged); Director of Ceremonies the ubiquitous Sir Albert Woods ‘Garter’ (and intimate of everyone worth the effort, with especial emphasis on the King to be). It was Woods who presided over Prince Edward’s investiture as Grand Master of English Masons in 1875. Sir Albert and his Prince can be seen in an engraving of more topical interest. Published in tangential coincidence with the beginning of the Ripper terror, it appeared in the Graphic, 4 August 1888.

Sir Albert stands next to Prince Albert Victor, the Duke of Clarence, who himself stands next to one of his father’s pals, the Earl of Lathom. The Prince of Wales wears the Holy Cloak; Sir John George stands at his side with sword raised in a tradition of fealty stretching back to the Crusades. And last but not least, we see Masonic historian and Commissioner of Metropolitan Police, Bro Sir Charles Warren.

Warren was well in favour with his future King, a house-guest at the country pile where Edward would guzzle, gamble, hunt, and fuck other people’s wives. In January 1888 ‘The Prince and Princess of Wales were present at a special meet of the West Norfolk Hunt at Sandringham, the principal guests of their Royal Highnesses taking part in the sport.’ The occasion was Clarence’s twenty-fourth birthday, and ‘Bro Sir Charles Warren arrived at Sandringham on a visit that same day’.16 Broadening the legal side of life, Edward’s intimates further included Lord Brampton, ‘the clever, witty, and eccentric judge’ better known as Sir Henry Hawkins (who had put Ernest Parke in prison), and the corpulent Sir Charles Russell, who, as already noted, was to become a star performer in the so-called ‘Maybrick Mystery’.

All were members of a self-regulating occult matrix in which everyone knew everyone, and everyone knew in which direction the bowing was done. ‘In every age monarchs themselves have been promoters of the Art; in return Freemasons have always shown an unshakable devotion to the Crown and its legal government.’17 Fealty was the name of the game, and somewhere inside it was a psychopathic bomb that could have shafted the lot of them.

Jack the Ripper had the guile of Satan, and would bring catastrophe to any who had a mind to challenge him. He was the embodiment of corruption, and corrupted whatever came into his sphere. Fear was his power, far beyond Whitechapel. It was an idiosyncratic fear with implications right to the top.

Was Warren – or anyone else – going to put the ruling elite at risk for a handful of whores? Endless falsehoods answer the question, endless nonsense underlines it. In order to protect themselves the Establishment would do anything in their power to brazen out any criticism, fix any court, and tell any lie.

Warren wasn’t an evil man, far from it, but presented with so unique an evil he became its supplicant. I have to admit to a momentary sympathy for Charlie – a man of his age – when faced with the momentous dilemma on that wall at Goulston Street. Never mind Commissioner Smith’s City Police photographs, the pictures below were etched into the very essence of Warren’s being.

Warren had less than forty days to survive as Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, and he devoted every one of them to breaking the law. Motivated by misplaced loyalty and authoritarian hubris, a coterie of senior officers at Scotland Yard conspired to create and coordinate an environment that couldn’t have been more favourable to the psychopath in their midst.

‘The Whitechapel Murderer is certainly a marvelous being,’ wrote the New York Tribune. ‘He is not only able to carry out his bloody work without molestation, but may even have it in his power to overturn a government.’18

Jack had a ‘Funny Little Game’, and survival was the name of Warren’s, articulated most succinctly by the Birkett Committee some sixty years later. ‘The detection and suppression of crime,’ it opined, ‘is essential to good government in any society, but not so fundamental as the security of the state itself.’19

Audi, Vide, Tace.