Every time I try to recall that trip to Havana, the events get jumbled in my mind. I remember feeling all kinds of emotions, partly due to a lack of sleep. I was utterly exhausted, but it was more than that—I think I was now absorbing all the disturbing experiences of recent days and weeks. Whatever the case, I had now embarked on a particular road and I had no doubt it was the right course. It was a time of tremendous expectations and heightened emotions. Leaving Santa Clara in that impromptu convoy, I left behind many of my youthful dreams, although some were now becoming reality.

We made our first stop to refuel at dusk. I think this was in Los Arabos, but it might have been Coliseo. It was a place I knew, having passed through there during my time in the clandestine struggle. But what I could never have imagined was that this place would become so special to me for the rest of my life. In that small, apparently insignificant town, Che first declared his love for me.

We found ourselves sitting alone in the vehicle. He suddenly turned to me and told me he had realized he loved me that day in Santa Clara when the armored car suddenly came up behind us. He said he was dreadfully afraid that something might happen to me. I was exhausted and half asleep, so I was hardly listening to what he was saying. I didn’t even take it very seriously, as I still saw him as much older than I was. I had previously had professions of love from others. Moreover, he was my leader, someone I respected and admired. He might have expected some kind of response from me, but at that moment I couldn’t utter a word—I was so tired. Also, I thought perhaps I hadn’t heard him correctly and I didn’t want a repeat of the “Caterpillar” incident.

Looking back, I think Che didn’t exactly choose the best moment to declare his love, and I felt a bit upset later thinking he didn’t get the response he might have hoped for. But that was it. The others piled back into the jeep, and we were soon on our way again. But the ice had certainly been broken.

We stopped in the town of Matanzas that night. We met up with some of Camilo’s troops, and I recall us having something to eat. Che called Camilo from the old telephone company. Camilo was already at Camp Columbia in Havana, and they were able to update one another about the situation. The next day we set off again. A small group of Che’s Eighth Column led by Víctor Bordón had gone ahead with Camilo’s men, and another group stayed at the Matanzas regiment, under Julio Chaviano’s command, in order to maintain order. This was Che’s reason for passing through Matanzas on the way to Havana. A few days later, Chaviano joined us in Havana to report to Che about the situation in Matanzas.

Some of us still debate what happened on the next part of the trip to Havana, probably because most of us were from the country and not familiar with the route. My memory is that we stayed on the main highway, and we came into Havana via Cotorro, on the port road and through the tunnel near the bay.

We reached La Cabaña Fortress in the early morning hours of January 3. The head of the fort (Colonel Manuel Varela Castro) was waiting for us. He belonged to the group known as the “pure soldiers” that included José Ramón Fernández and others—soldiers who had been won over to supporting the revolution. Che was told about the unarmed troops stationed at the barracks and he decided not to go there. He went instead to the Military Club, where the non-commissioned officers and prisoners were being held. The officers still had their handguns.

As we made our way to the old army headquarters, there was an eerie calm about the city. After some discussion, we went to the army commander’s house in La Cabaña, where we met Lieutenant-Colonel Fernández Miranda (Batista’s brother-in-law) and several other high-profile Batista men.

What took place there was quite surreal. It was strange to be in such an enormous fort, watching the soldiers subordinate themselves to the rebel command. This revealed the low morale of Batista’s army. More importantly, it showed the trust in and respect for the new Rebel Army, which had proved it had the unconditional support of the Cuban people.

Che and others set up their command post in Fernández Miranda’s house, and we stayed the night there. Most of the men slept in the main room, while I was given the smallest separate room. I slept only a few hours as we still couldn’t allow ourselves much time to rest. A few of the women with us searched for a change of clothes among Fernández Miranda’s wife’s things. That morning Che set himself up to work in a small office in the house, but later transferred his office to the army headquarters within the fort. Walking around La Cabaña, we were in awe of the magnificent gardens and the view of the sea, marvelling at the incredible beauty of the place. We, the dispossessed, for the first time felt ourselves masters of our own destiny. But, as Che had always warned, from that moment the real revolutionary struggle would begin.

A new life began for all of us. The initial chaos gave way to order, and we took the first steps in organizing ourselves, occupying other houses within the fort. On January 5 we took a plane to Camagüey. I had no idea where we were going and even less who we would meet there. During the trip Che dictated some notes to me about the duties of a rebel soldier. This is how I began my first job with him, without it ever being officially decided. Che was aware of the need to jot down his thoughts to assist the process of the revolutionary transformation that had begun.

I stayed in the airport with Commander Manuel Piñeiro (Barbarroja)1 and Demetrio Montseny (Villa), and then we later returned to Havana with Che. The purpose of the trip, as I later discovered, was to meet with Fidel, who was coming in a triumphant cavalcade from Santiago to Havana. They discussed the next steps to be taken and what new orders should be issued. This meeting at the Camagüey airport was captured in a famous photograph that shows both men in a happy, relaxed mood.

A few days later, on January 7, we traveled by car to Matanzas, where Che again met with Fidel. I waited nearby and I met Celia Sánchez2 for the first time, and later that day Che introduced me to Fidel. I wanted to say so much to him, but somehow the words abandoned me. I wanted to say how much it meant to meet him and how I felt as though I had known him for a long time. He was the reason I felt my life had a purpose and meaning. I had so much to thank him for, not only because of what had happened historically, but also because if it hadn’t been for him I would never have met Che.

We returned to Havana that same day to wait for Fidel. On January 8 from our vantage point on the walls of La Cabaña Fortress, we watched Fidel arrive in Havana. Looking across the bay we could see the huge throng of people crowding around the rebels.

Gradually a certain measure of order was established, despite the excitement and turbulence of the revolution. I, too, began to create some kind of order in my personal life and to adapt to my new life in Havana.

I had to start to do normal, everyday things, or at least try to lead a normal life. I decided to abandon my guerrilla fatigues and dress like a woman. I went with Lupe (Núñez Jiménez’ wife) to her mother-in-law’s house. She was a dressmaker and she made me a pretty, fashionable dress. Lupe and I also went to the hairdresser together. I soon began to feel like my old self again. We walked around central Havana, acquainting ourselves with the beautiful parts of our capital city for the first time.

Che’s bodyguards accompanied him everywhere, on his way to work or if he and I took a stroll together along the Malecón, Havana’s famous sea wall. Neither of us knew our way around the city. We would often get lost or stop at a red light thinking it was a traffic light, only to realize it was the light of a pharmacy. We laughed a lot about this, paraphrasing the title of a film by referring to ourselves as the “campesinos in Havana.”3 We were simply two people in love, ruled by our feelings. Sometimes, if he was driving the car, he would ask me to fix the collar of his shirt or he would tell me his arm still hurt so could I fix his hair—these were his sly ways of getting me to caress him in public before we were married.

We lived every minute to the utmost. My friends from the Presbyterian Church invited me a couple of times to attend church with them. Once Che drove me to church in his car, and left me at the door, saying he would pick me up an hour later. I had a wonderful reunion with my old friends Faustino Pérez, Orestes González, Sergio Arce (who had been my pastor in Santa Clara) and the widow of Marcelo Salado. Che always respected my opinions and told me what he thought. Over time, with the impact of the social transformation taking place around me, and under Che’s influence, my attitude to religion changed.

I can’t recall who picked me up from the church that time. It was probably one of the bodyguards, and we then went to pick up Che from Ciudad Libertad, as Camp Columbia was now called. In those first days we spent quite a few nights there with Camilo. At other times, Camilo would come across to La Cabaña. Camilo had a reputation as a ladies man. One day he stopped by when Che wasn’t around and put me on the spot, bluntly asking me about my relationship with Che. I responded curtly that I was only his secretary. Backing off, he half-jokingly insisted he had only stopped by to see Che, and that was the end of it. Everyone loved Camilo and I took no offense.

La Cabaña Fortress became one of the crucial centers of the revolution, and Che began to emerge as one of the more able and charismatic leaders. The leadership of the new revolutionary government had to be created from a largely illiterate group of former guerrillas, who were not very well prepared for the challenges that lay ahead. Within a few days of Che’s arrival, La Cabaña was transformed into a sizable cadre school. Small factories and workshops were established there, similar to those he had organized in the Sierra Maestra. He saw the process of industrialization as an urgent priority for the country. A small magazine called Cabaña Libre was produced, promoting discussion of cultural issues. Events were organized at La Cabaña, attended by important national cultural personalities, such as the poet Nicolás Guillén and Carmina Benguría.

The main objective of these activities was the political and cultural development of the Rebel Army soldiers. A great emphasis was placed on literacy classes because the former rebels were often undisciplined and reluctant to study. During the war they had been courageous, an inspiration to others; but they now found it difficult to understand why so much was demanded of them.

This meant an extra burden for Che. Besides the multiple tasks of his daily work, he also committed himself to describing and analyzing the experiences of the revolutionary war in Cuba. He thought such an analysis might offer lessons to other revolutionary movements or national liberation struggles. By this time, Che’s talent for military strategy was widely recognized, but nothing was known about his remarkable grasp of revolutionary theory, despite his reputation as a communist.

Che’s speech at the cultural society Nuestro Tiempo, a few days after the triumph of the revolution, alerted both friends and enemies to his considerable intellect. In that speech he clearly outlined how he saw the Rebel Army as the vanguard and the source of future cadres for the revolution. As much as time would allow, he analyzed the Cuban revolution from a Marxist perspective—something he would go on to develop in greater detail. This became an important aspect of his legacy.

We all faced a daunting workload. The revolutionary tribunals, organized in January, put on trial those henchmen of the dictatorship who had not succeeded in fleeing with Batista. This was done in conjunction with an investigative commission, presided over by Miguel Angel Duque de Estrada, a lawyer and captain in the Rebel Army.

These tribunals have always been controversial, and the facts about them have often been greatly distorted by our enemies. For Cuba, they were a legitimate form of revolutionary justice, being neither without mercy nor spontaneous. The proper procedures were followed, and I recall that Che participated in some of the appeals, meeting with the families who came to beg for clemency. We adopted a humanitarian approach respectful of the prisoners. Although the process of the tribunals was just, it was, nevertheless, painful and distasteful. Che did not attend the trials nor was he present at any of the executions.

Oscar Fernández Mell, Adolfo Rodríguez de la Vega and Antonio Núñez Jiménez were Che’s assistants in La Cabaña. The military intelligence organization was created, and Arnaldo Rivero Alfonso was put in charge of monitoring the behavior of rebel soldiers.

The amount of work I faced was quite overwhelming. I had to attend to the needs and personal problems of the soldiers, according to Che’s instructions. I also had to try to control the number of personalities and journalists who came to Havana to interview Che. Among these national and international visitors were Herbert Matthews, Loló de la Torriente and women from many different professions, who sought an audience with Che. My role as Che’s personal assistant gained me the rather unjust reputation of being jealous and possessive. I also had to deal with the future girlfriends and wives of Che’s assistants and bodyguards.

Former combatants in the underground movement turned up to see for themselves the “communist” who had liberated Las Villas. Others came to see the legendary combatant, who had risked his life for a country not his own, like Máximo Gómez. Gómez was born in the Dominican Republic and came to Cuba to fight in the independence wars against the Spanish. Like Máximo Gómez, Che was declared a Cuban citizen after the revolution.

My temporary office at the residence was also my bedroom. I inherited the previous residents’ dog, which for some reason hated soldiers. I never figured out if he only hated our soldiers or if his dislike was more general. Along with the dog, a lot of other things had been left behind, including films of the family of the former military commander of the fort. When we left La Cabaña and moved to Tarará, we took the dog with us, and he remained with us until he died.

I began my role as “treasurer,” managing money we still had from the days in the Escambray. I still have those documents and receipts from that time. We maintained strict austerity with regard to our funds. Che ordered a distribution of 10 pesos to each soldier for their holidays.

I also handled Che’s personal correspondence. Around January 12 he asked me to read a letter he was sending Hilda (his former wife). He told her they needed an official divorce because he was going to marry a Cuban woman he had met during the struggle. I didn’t quite understand his handwriting, so I asked him who was the young woman he intended to marry. He looked at me with surprise and said it was me. The fact is, up until that moment, we had not discussed marriage. Without saying another word I processed the letter. Che’s answer surprised me. It wasn’t exactly unexpected, but at the same time I wondered why he hadn’t ever mentioned this before.

There were other letters, including one he sent to his beloved Aunt Beatriz, which we joked about. This aunt loved Che dearly and idolized her favorite nephew. When he told her he was separating from Hilda and was going to marry me, she wrote somewhat disparagingly about “the girl from the sticks,” in a tone that reflected the prejudice of the Argentine oligarchy to which she belonged. It was innocent enough, but demeaning to me. Sometime later, when I met Che’s parents at the airport, the first thing Che’s father asked him was whether I was “the girl from the sticks.”

By that time, our relationship had changed. During January we took a trip to San Antonio de los Banos. This time, we were both sitting in the back seat of the car, and for the first time Che took my hand. Not a word was spoken, but I felt my heart would jump out of my chest. I didn’t know what to do or say, but I realized then that there was absolutely no doubt I was in love with him.

Not long after that, on a memorable January night, barefoot and silent, Che came into my room in La Cabaña, and we consummated an already strong relationship. Che jokingly called that day, “the day the fortress was taken.” The expression is probably apt because, when you take over a fortress, you must first surround it, determining its weak points, before you decide on the attack. I was even more in love than I knew, so I “surrendered” without resistance.

Everything happened quickly after that. Che’s parents arrived on January 18, and we went to meet them at the airport. His father immediately asked who I was, and Che introduced me as the woman he intended to marry. We then went to the hotel where they were staying. It was a very emotional time because from the moment he saw his parents Che exuded happiness. It had been nearly six years since he left his home in Argentina.

During his parents’ visit we went to Santa Clara and El Pedrero. That place, where Che had invited me to get into his jeep and “shoot a few shots,” marked a decisive moment in my life.

On a personal level, not everything was entirely without difficulty. In the midst of the whirlwind of our lives in these first weeks of the revolution, Hilda arrived. No arrangements had been made for her accommodation. We still lived in the barracks at La Cabaña, with Batista’s former soldiers cooking and cleaning for us, and doing other chores around the place. Che was busy learning to fly a plane. Eliseo de la Campa had been his pilot and he owned the plane in which he was teaching Che. Che had planned a trip to the Isle of Pines and, when he heard the news of Hilda’s arrival, he came to see me. I was quite ill in bed with rubella. He invited me to join him on his trip. So I immediately got dressed and left with him.

Alberto Castellanos went to collect Hilda at the airport. Che’s parents were also waiting for her. When I returned from the trip, Hilda and I were not introduced, but I did manage to catch a glimpse of her. My illusions about her vanished, and my ego was somewhat boosted. In no way could I consider her my rival. I also felt less guilty because it was clear from the letters Che had sent to his family from Mexico (when I wasn’t even in the picture) that his relationship with Hilda had ended. We now only had to overcome a few obstacles Hilda had created. These problems were inevitable and, although I was upset at the time, now I can look back much more calmly.

Otherwise, life continued almost normally. We regularly visited the renamed hotel Havana Libre (previously the Havana Hilton), which had become a temporary central headquarters for the rebel troops. On one of those visits, when Che was meeting with Fidel at the hotel, I was waiting in one of the rooms. I was on the bed, chatting to Celia Sánchez and Pastorita Nuñez, when Fidel came in and told me I was in his spot. I was mortified and got up immediately. It was a joke, but at the time I didn’t know him well and I thought he was reprimanding me. That room was always packed with people, because many of our compañeros with different responsibilities would go there for meetings and often had to wait patiently for hours. I remember on one occasion I saw Augusto Martínez Sánchez sleeping on the floor while he waited his turn.

Another time, I was sitting on a chair next to the door of that room, and Fidel burst out suddenly with his bodyguards. On seeing me, he stopped for a moment, looked at me and asked—just to be sure—if I was “Che’s girl.” As you can imagine, I was embarrassed by the question and responded in my usual way saying, no, I was Che’s secretary. Sometimes I would say I was his assistant, as I was not in the military, only a former guerrilla. This lack of clarity created a lot of confusion.

During my time at La Cabaña, I received some personal tuition from Armando Hart, our very young, talented Minister for Education. Many people were aware I had completed the final year of my pedagogy course at the Central University in Las Villas. Therefore, Armando decided to honor me with the title of “Doctor of Pedagogy,” based on my “practical thesis” on the role of women in society, which I had achieved during the war. I have to admit this gave me much pleasure as I did feel I had earned it.

Many foreigners came to see Che, including a group of Haitians, who came to seek Cuban support for their efforts to overthrow the dictatorial regime of Duvalier. With hindsight I realize that even as early as February 1959 steps were being made to establish Cuba’s collaboration with liberation movements and other progressive struggles. I feel privileged to have witnessed this. As a result of those initial conversations with the Haitians, Che sent me to the Sumidero area in Pinar del Río with Hernández López, the captain who later married us in La Cabaña. He was a compañero from the underground struggle in Havana, and had first met Che in Fomento, where he had been sent by the July 26 Movement to work on propaganda. Hernando and his wife, Gloria Pérez, worked with Che until he left for the Congo.

The month of February came around, and so did my birthday. It was not a particularly happy time because Che was already showing symptoms of pulmonary emphysema, as a result of the privations of the war and the pressures of the first, hectic days after the revolution.

My old friend, Lolita Rosell, came by to wish me a happy birthday. I was sitting with Che in his room. She didn’t really need to ask; she only had to see us together to sense the intimacy between us.

In the first days of March we moved to a house in Tarará on the beach outside Havana, hoping Che would regain his health in a quieter place and have some respite from his never-ending responsibilities. His bodyguards, whom I always regarded as brothers, came with us. I often had to defend their lack of discipline, and occasionally I was complicit in their nightly escapades. I understood they were young men from the country, many of them from remote villages. They were totally awestruck at being in Havana for the first time—a glittering city of endless nights and beautiful women. They would often sneak out late at night to meet their girlfriends, taking the car. They would roll the car down the hill before starting the engine, so as to leave undetected. Che would ask me if I had heard a noise, probably because he knew what was going on. I would answer, no. I don’t think he believed me, but he would let it go at that.

I, too, did some pretty crazy things. I was a terrible driver, only just learning to drive. Roberto Cáceres (El Patojo or “Shorty”), a Guatemalan whom Che had met in Mexico, would often accompany me in the car. He had just arrived in Cuba. Tragically, he died some years later fighting for the liberation of his country. They were wild, romantic times. We were young and did things maybe we wouldn’t do in other circumstances. We drove around Havana in a huge Oldsmobile, without a clue as to where we were going, but somehow we always arrived at our destination.

We had a lot of fun in those days. Eliseo, Che’s pilot, once decided to land his plane in the streets of Tarará, much to everyone’s astonishment. I remember them all—Villegas, Hermes Peña, Argudín, Castellanos and others—with deep affection.

The house at Tarará was quite elegant, having previously belonged to a customs officer with links to the dictatorship. After we moved into the house, Che received a malicious letter that was published in the magazine Carteles. It asked where the money had come from for such luxurious living, the implication being that it could only be money stolen from the people.

It turned out we only lived in that house for two months and, although it never became much of a home, I have very happy memories of that time. We never had time for a proper rest and we didn’t spend a single day at the beach. But it was a wonderful time for Che and me, and was where we were able to achieve a greater sense of intimacy than ever before.

Che gave me his first personal gift there—a bottle of Flor de Roca perfume from Caron. In reality, we didn’t have a lot of time to ourselves; compañeros were always coming and going, working on various tasks that couldn’t wait. Relatives of those facing execution also came to see Che there. Even the sister-in-law of the former owner of the house showed up, saying she had never been invited there before.

Nevertheless, it was a comfortable house where Che was able to use his bedroom as an office. Being ill, he could remain in bed most of the day when he didn’t need to travel to La Cabaña. This gave me a lot of freedom. We breathed a different air; the house had large windows and was well ventilated. It had a small, separate office on the ground floor, and upstairs was Che’s large room next to a large bathroom. Because we were not yet married we had to make it appear we slept in separate rooms. So I had my own bedroom. The bodyguards slept in a room at the end of the hall.

There was a large room used for meetings, where many important discussions took place. The first Agrarian Reform Law document was drafted there. There was also a dining room and a modern kitchen, which led to the garage with a small storeroom where the previous owner had stored all kinds of delicacies.

Our household included Téllez, del Sol, Díaz the cook, and also Castillo, all of whom had come with us from La Cabaña. Some of these compañeros made up part of the permanent security garrison in our various houses over the next few years. Che implemented a disciplined regime for the men, including formal lessons with a teacher so that the soldiers of Che’s bodyguard could maintain their education program.

Che and I had a few misunderstandings. Once a group of Nicaraguans came to the house and, to my surprise, Che sent me out of the room while they met. I didn’t understand this because I had attended similar meetings with the Dominicans, Panamanians and Haitians. I left the room and started to cry, beginning to doubt whether Che trusted me. He explained later that he had expected it to be a very tense meeting, when unpleasant things would be said that he didn’t want me to hear. He apologized, saying he had expected the Nicaraguans to be quite agitated. I came to understand the importance of these meetings.

If I regret anything now, it would be my failure to understand the need to document such meetings for posterity, even by taking brief notes. None of us really understood the extent or real significance of what was happening, nor the transcendent nature of our role in the development of groups that came to lead liberation movements throughout Latin America. I wasn’t asked to take notes of those meetings, even though I was always present. Now, when I want to write about those events, I can’t remember everything because of the years that have passed.

One of the revolutionary laws most eagerly anticipated in Cuba—the Agrarian Reform Law—was drafted in that house in the little seaside town of Tarará. Che assumed this responsibility, mainly because Fidel had given him and Sorí Marín that task during the Sierra Maestra days. On reaching the Escambray Mountains, Che applied the law promulgated in the Sierra Maestra in the new territories under his command. The drafting meetings took place on a daily basis over many nights. Fidel was living nearby in Cojímar at the time and he came as often as he could. Others attending these meetings were Raúl and Vilma, Núñez Jiménez, Oscar Pino Santos and Alfredo Guevara. The final draft of the document was presented in May 1959.

Carlos Rafael Rodríguez4 would also visit our house regularly, and I remember his visits well. They would stay up practically the entire night discussing revolutionary theory and practice. These discussions preceded a debate on political economy and the transition to a post-capitalist society, a debate in which both Che and Carlos Rafael were key participants.5

Not everything went entirely smoothly in Tarará. There was a misunderstanding about my first pregnancy and miscarriage. I had gone to an event at the Capitolio, where I had a fall. That night I started to bleed and, as a result, I had to have an abortion the next day. I went to the hospital with Fernández Mell because Che, being such a well-known figure, felt he couldn’t take me, and he wanted to avoid the attention. Che was very upset about what had happened. He thought I had wanted an abortion because we weren’t yet married. I could not convince him that was not the case. I was not able to get pregnant again for another eight months, and he often joked that he, like the Shah of Iran, could not have children.

By the end of April, there was great excitement throughout the island. For the first time in Cuban history, we would have a May Day celebration that was a true expression of the Cuban workers’ power. Che had recovered from his illness, so we were able to travel to Santiago de Cuba for the celebration in the company of Calixto García, Manuel Piñeiro and compañeros of the Revolutionary Directorate. I can still see the people marching with joy, for the first time in their lives envisaging a better future. The weapons carried by the soldiers were no longer used to repress the Cuban people. Instead the rebel soldiers were mixed in with the masses who carried tools to be used in the construction of a new society. It was the exuberant expression of a united people, willing to defend what they had won.

On May 3 we traveled to Las Villas province, passing through Sancti Spiritus, where we met up with Camilo. That was where Che exchanged his beret for Camilo’s hat, an incident captured in a famous photograph. In Santa Clara, we met my family, whom I had not seen for some months. I stayed with them for a few days and then returned to Havana alone. A few weeks later, on May 29, Che came to tell me Hilda had finally signed the divorce papers. We could then commence the preparations for our wedding. He also officially informed my parents. We then moved to a new home, a rented farm house near Santiago de las Vegas, a pleasant location, slightly outside the city.

I returned to Santa Clara so that a friend could make my wedding dress, a very simple dress. I would often stay at Lolita’s house when I traveled to Santa Clara so that my parent’s traditional attitude was not challenged. The wedding took place on June 2, 1959, at La Cabaña Fortress. We wanted an informal ceremony, and Hilda had requested that no media attend the wedding. But when Raúl Castro found out, he took it upon himself to organize a party for us. I got dressed at Lupe’s home, and the marriage ceremony took place at Alberto Castellanos’s home in the fortress. Everything was modest, with only a few people officially invited. We thought there would be no celebration or toast, and only a small group of people. But others conspired against this and organized a big party, attended by Raúl and his wife Vilma, Celia Sánchez and her sisters, my family and some friends from Santa Clara, as well as compañeros from Che’s column. Later on Camilo and Efigenio Ameijeiras (who was chief of police and who, incidentally, got a speeding ticket that night), arrived bringing others I didn’t really know. Everyone signed the guest book. Unfortunately, nobody had told Fidel, the celebration having been organized in semi-clandestine manner. He showed up complaining he hadn’t been invited. He signed the guest book, and then he left shortly afterwards. That is how our wedding took place. The next day it was front page news.

The wedding was a natural step in our relationship, the culmination of the first stage in our life together—a brief, intense and extremely happy period. After the party, we returned to our home in Santiago de las Vegas for our honeymoon. Juan Almeida was waiting at the house to congratulate us, so we chatted with him for a while. Then, finally, we had time to ourselves. But it was very brief as early the next morning Che’s daughter, Hildita, arrived. Her mother had sent her as a wedding gift, maybe thinking we wouldn’t want to have Hildita living with us. But Che was always very happy to have his daughter with him. I remember he took some photos of Hildita, one with a cat we had at the time. This was the beginning of our married life.

We had some special moments at the Tarará house, and we also experienced wonderful times in our home in Santiago de las Vegas. The revolution was advancing at lightning speed. We were getting better organized and uniting all the revolutionary forces. Raúl Castro and Che held regular meetings with members of the Popular Socialist Party (the former communist party). These meetings were held in secret. They discussed how to overcome the anticommunist sentiment still very much alive in Cuba at the time. I have to admit I was still influenced by my rural background, and I told Che I didn’t trust Aníbal Escalante6 and some of the others who came to our house. It seemed like a conspiracy within another larger conspiracy.

I also met the Argentine Jorge Ricardo Masetti,7 who was encouraged by Che to form the news agency Prensa Latina. Che originally proposed that I become the head of the press agency. He said he would help me with the experience he had gained in Mexico and the Sierra Maestra. But I refused, thinking I was not ready for the role. Perhaps that is why I always admired Haydee Santamaría, who demonstrated not only intelligence but also a fine sensibility when she became head of the prestigious cultural institution, Casa de las Américas, despite her lack of formal education.

During those months of hectic activity, I somehow managed to focus on my personal life: I finally learned to drive properly, I exercised and read a lot. I started to read Russian and Soviet literature, and my political views slowly began to “redden” under Che’s influence—he always had great powers of persuasion. The more I came to know him, the more I understood his total dedication. He tried to convince me about communism, patiently clearing up my misconceptions, without me feeling that he was forcing his views on me. We talked about all kinds of things, including some of the issues that arose during the revolutionary war such as the relative importance of the urban underground movement and the guerrilla struggle in the mountains.8

Che had many responsibilities in the new revolutionary government. In May 1959, Fidel suggested Che travel to the countries comprising the Bandung Pact. This international alliance later formed the Movement of Nonaligned Countries. Fidel always placed great importance on our relationship with these countries, and their support for Cuba at the United Nations General Assembly was decisive. This also meant we dealt with representatives of those countries as equals. That trip led to Che becoming the principal representative of Cuba’s foreign policy.

Nevertheless, the trip came at a difficult time for me. Che left Cuba on June 12—only 10 days after our wedding—and he didn’t return until September. Due to the length of time he would be away, I suggested I go along as his secretary. He strongly rejected this idea. This taught me a lot. He argued that, apart from being his secretary, I was also his wife, and it would be seen as a privilege if I were to go on the trip with him, when other wives or girlfriends were not able to. Before he left, we went to see Fidel, and he also tried to convince Che to take me along. But Che would not be moved. I started to cry, and this made him angry. It was a difficult time for him, too, and I was making it worse. While Che was away on that extended trip, Fidel suggested I join him in Morocco or Japan; but Che would still not change his mind. Instead, he sent me postcards from those faraway, exotic places, describing his experiences. The first one arrived from Japan:

My darling,

Today I write to you from Hiroshima, where the bomb was dropped. On the catafalque that you can see are the names of more than 78,000 people who died, the total number is estimated to be 180,000.

It is good to visit this place so that we can fight for peace with more energy.

Big hug,

Che

Towards the end of the trip he wrote from Morocco, this time in a lighter tone, expressing his eagerness to return home:

Aleiducha,

From the last leg of the journey I send you a faithful marital hug. I had hoped to remain faithful, even with my thoughts. But the local Moorish women here are truly stunning...

Kisses,

Che

Perhaps because he felt slightly guilty about this trip, Che always spoke about us taking a trip together to Mexico, so that I could see for myself that country and its wonderful Mayan and Aztec cultures. This was, of course, just a fantasy because we faced such a huge workload. Nevertheless, the idea of traveling together remained our fantasy.

On his return from that first major overseas trip, Che quickly resumed his incredible workload. On August 7, 1959, he was designated head of the Department of Industry of the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA). He asked me to come and work for him as his personal secretary. I was reluctant at first, but when he told me, with an ironic grin, he had been assigned a pretty secretary, I changed my mind. I reported for work at his office the very next morning.

My future role had been decided in the first days of January when, on a trip around Havana, Raúl Castro asked Che what rank I would be honored with. Che bluntly replied, none, because I would be his wife. I accepted this, although some may not understand my position. I have never regretted the decision, which I think brought us closer together and helped reinforce our relationship, especially for Che, who had been alone for such a long time.

We wanted to make a home with children. I didn’t care about appearing in photos with famous celebrities. I was happy in my anonymity, always taking pleasure just in being by Che’s side. Was this because I suspected we might not have much time together? I know how happy he was in those days, in the few moments in which he could escape into our private world. In a letter he wrote to me years later from Paris (in 1965) he commented: “I am definitely getting old. I am more in love with you each day and my home beckons me—the children and the little world that I can only sense rather than experience. Sometimes, I think this is dangerous, diverting me from my duty. Moreover, you are so essential to me and I am only a habit for you...”

When I went to Che’s INRA office on that first day, despite what Che had told me, to my surprise I bumped into an extremely pretty girl, well-groomed according to the fashion of the time. I immediately asked who she was and what she was doing there. They explained she was the wife of Nuñez Jiménez (director of INRA) and he had assigned her to work as Che’s secretary. I requested she leave immediately because I was the only secretary Che needed. Everyone else in the office agreed and covered up the fact that I was responsible for the removal of the director’s wife.

When Che arrived, he made a sarcastic comment about his new secretary having disappeared, and he reminded me he was not the head of INRA. It wasn’t until many years later, when we were in Tanzania, that I finally confessed my part in the secretary’s disappearance. By that time I no longer experienced such bouts of jealousy, and he would actually complain I was no longer as jealous as I had been! He didn’t realize that by then I was far more secure in our relationship.

Despite my reputation as a jealous wife, in my role as his personal secretary I never read Che’s private letters; he knew this and trusted me completely. On one occasion, a compañero asked him why he had me as his secretary and why he would want to work with his wife. Che replied with good humor, and with no ill feeling, that the decision had been entirely his, and he was very happy to work with his wife.

The work piled up, especially after the revolutionary government’s Law No. 851 (Article III) passed on June 6, 1959, giving INRA responsibility for the Department of Industry. This responsibility included the Cuban Institute of Oil and the administration of all expropriated companies.

At this stage the first plans for industrialization were made, the main objective being to create industries that would save precious dollars by producing a range of urgently needed consumer goods that could substitute for imports.

Che recognized the importance of nickel mining. Cuba has large reserves of this metal, and processing plants had been built and exploited by US companies in Oriente province. In order to operate the plants, we needed special technology that the Yankees refused to share with us after the plants were expropriated.

Cuba not only needed skilled technicians, but also needed people to put their hearts and souls into meeting the challenge of industrialization, qualities Che had in abundance. He was greatly assisted by Demetrio Presilla, an engineer and the only technician who had stayed working at the Moa mine after the revolution. Given the importance of the mining industry, we traveled almost every weekend to that area in the far east of the island. The plant was eventually reopened and contributed significantly to the economic development of our country.

Che made a point of meeting some of the nickel miners to learn first hand about their appalling exploitation. They had a poor diet and little education. Their grueling physical labor, and its contribution to the economy, was not recognized. Gradually measures were taken to humanize their work, and the miners gained a sense of dignity. They were immediately provided with better food in workers’ meal rooms and they were allocated better housing. For the first time in their lives they were treated like human beings. Che took a great interest in these previously neglected mining communities. He even took photos of one place called Imías.

José Manuel Manresa worked at INRA’s Department of Industry as office manager, and El Patojo (Che’s Guatemalan friend) acted as his assistant. Other Latin Americans also collaborated with the department, including economists Juan Noyola, Carlos Romeo, Jaime Barrios, Álvaro Latoste, Raúl Maldonado and others, all of whom followed Che when he went to work at the National Bank. Most of them were advisers in the project that eventually became the Ministry of Industry. They also carried out tasks related to the nationalization of factories, the collection of taxes, assisting with queries and complaints, and dealing with large companies such as the sugar mills and tobacco manufacturers like Partagas.

Aside from reopening the key mining complex at Moa, in the first year of the revolution Che was also involved in the construction of the “Camilo Cienfuegos” school complex in El Caney de las Mercedes. This work was carried out by Che’s former column. In the months of June and July, part of the column was sent to Oriente and another part went to Santa Clara.

The construction of the school complex fulfilled one of Che’s dreams. He thoroughly enjoyed his visits there, laboring alongside his compañeros.

When Che was named president of the National Bank on November 29, 1959, we moved house again, this time to Ciudad Libertad, formerly Batista’s military camp (Camp Columbia), which was later transformed into a large school campus. Raúl Castro and his wife, Vilma, and other compañeros also lived in Ciudad Libertad at the time.

In the whirlwind of the first year of the revolution, Che played a part in the formation of the G-2 Cuban Intelligence Service, formed to guarantee the safety of the revolution. He was also in charge of the first delegations arriving from socialist countries, without ever neglecting his other multiple responsibilities.

Sometimes Che had to resolve minor problems involving the members of his bodyguard, for example when his compañero Harry Villegas accidentally fired a shot killing another compañero when the bullet ricocheted off a wall. Che sent Villegas to La Cabaña to be detained and serve his sentence. This showed that, for Che, discipline came first, with no exemptions for anyone.

Che’s work at the National Bank was very stressful, because it meant creating an entirely new kind of bank. This required a massive effort and substantial time. Che immediately proposed new measures to stop the flight of capital from the country, which included breaking ties with the International Monetary Fund to which Cuba belonged and was meant to contribute $25 million. The Economic and Social Development Bank was liquidated along with the National Finance Company and the Cuban Foreign Commerce Bank, institutions that represented a drain on national funds.

An official of Cuba’s National Bank was ordered to withdraw Cuba’s gold deposits held in the United States. US banks in Cuba, including the Chase Manhattan Bank, the First National Bank of Boston and Citibank of New York, were all nationalized. A law was later passed nationalizing all Cuban and foreign banks, with the exception of Canadian banks. Another 44 banking enterprises were also nationalized along with their 325 offices and branches at 96 locations throughout the country. We purchased the two remaining Canadian banks, and a successful currency exchange occurred in 1961. This became possible when the first contracts were signed with the socialist countries in 1960. The famous bank notes with the simple signature “Che” were printed in Czechoslovakia.

All of this activity emanated from the central office of the National Bank with its tiny staff that included José Manuel Manresa, a highly qualified bilingual secretary named Luisa (whose surname I forget) and me as personal secretary, along with a group of assistants. Some changes had to be made because the carpet in Che’s office aggravated his asthma. It was replaced with a linoleum floor. We enjoyed our time there, despite the enormous workload. We felt like a little family, eating breakfast and lunch together at the far end of the building, near Che’s office. We had no fixed routine: we might eat at 8:00 p.m. or 3:00 in the morning, when we would have a hot chocolate with toast. We always enjoyed the company of other Latin Americans, who would tell anecdotes about their countries. This helped us to get to know one another better. Among these visitors were Carlos Romeo, Jaime Barrios, Raúl Maldonado, José Santiestaben and Salvador Vilaseca, a Cuban who later became Che’s mathematics tutor and who remained with him until Che transferred to the Ministry of Industry.

Among our memorable visitors was the Soviet delegation led by Eugenio Kosarev, a loyal supporter of Cuba, who became one of Che’s close friends. Somehow a typewriter with Russian characters materialized so that he could type up his reports. It might have been Graciela Rivas who found that typewriter—she was incredibly efficient. She was Manuel Aspuru San Pedro’s attorney and always did her best to assist us.

Another of our regular visitors was Jaime Barrios, a Chilean collaborator, who later died alongside President Salvador Allende at La Moneda Palace, during the tragic events surrounding the military coup on September 11, 1973.

At this time Che began to attend the official government receptions, something he didn’t particularly relish. He also attended the new cadre school and he would get very annoyed if a compañero failed to attend classes. Wherever he went, Che always wore his olive green uniform, which by evening would look quite crumpled and sometimes even dirty, depending on what he had been doing that day.

I remember one particular reception when Regino Boti, our finance minister and a good friend of Che’s with a great sense of humor, urgently called me over to tell me something. He commented, in a low voice, on how elegant Che looked that night. I glanced over at Che whose boots looked scuffed, as they always did, and whose uniform looked the same, a little crumpled perhaps. I couldn’t discern anything unusual in his attire, so I asked Regino what he meant. “Look,” he said, “he has not one, not two, but three pens in his pocket!”

Often, when we were ready to leave work and go home in the early hours of the morning, Alberto Bayo would show up to play chess with Che. Che had so little leisure time and so few pastimes that I would let them be. But this usually meant we would leave the bank almost as the sun was rising and we would be in a bad mood the next day.

Che always made time in his busy schedule to follow the construction of the “Camilo Cienfuegos” school complex. We would go there every week, always with Eliseo, a skilled pilot but, nevertheless, not immune from accidents. One day we got caught in a storm that nearly brought the light aircraft down. After Camilo9 died in a plane crash, we were prohibited from flying in these little planes, and we had to travel in a Cessna with two motors.

For Che these trips in light aircraft had many purposes; he loved to fly and usually piloted the plane himself. Sometimes he would fly over central Cuba along the route from the Sierra Maestra to Santa Clara, recapturing his experiences during the revolutionary war. When we reached our destination, Che would be in a great mood, taking charge of everything, chatting to the soldiers of his former column and asking about everything in great detail. We stayed the night sometimes, sleeping in bunk beds; he would take the top bunk and bring his hand down to hold mine—we would fall asleep that way. Despite the fact we were working, these were most enjoyable trips.

On one of our last visits to the school, we met Sidroc Ramos, who had just been named as its director. His wife, Berarda Salabarría, also worked at the school. The children were yet to arrive. Then in the distance, we saw them coming toward us, led by Isabel Rielo, who had been the captain of the all-female “Mariana Grajales” squad in the Sierra Maestra. I found it very moving, recalling my own painful separation from my family when I had to go to Santa Clara to study. If I had any talent for painting, I would like to have painted that beautiful scene. The children came from some of the most remote parts of the island, and would never have had a chance to study without this school. Their parents were happy for their children to be educated and showed confidence in the revolution. I remember how those children saw electric lights for the first time, commenting with surprise that the stars seemed very low in the sky that night. Such experiences filled us all, especially Che, with a great sense of satisfaction.

In November 1959, as part of a large Cuban delegation of more than 80 women compañeras from all social spheres, I attended the Latin American Congress of Women held in Chile. The Federation of Cuban Women (FMC) and other mass organizations did not yet exist. Nevertheless, prior to the congress we worked in commissions on different themes, with the aim of explaining to others the work of our fledgling revolution.

Che came to see us off at the airport, convinced about the significance of this trip for Cuba and for all of us. This was my first trip abroad. He was not mistaken about the importance of the tour. Journalists followed our every move in Chile, asking us about what was happening in Cuba. I appeared on the front page of one paper as “Mrs. Guevara.” It was a real learning experience for us, as we met labor movement leaders from many different countries. We confidently and effectively explained Cuba’s revolutionary process to anyone who would listen.

Chileans approached us in the street, questioning us about the changes that were taking place in Cuba. We met Salvador Allende (then a member of parliament) and dined at his house, along with the leaders of other delegations. This gave me my first glimpse into the world of diplomacy. I have but one regret about that trip: that I didn’t get to meet Pablo Neruda, one of Che’s favorite poets.

We returned to Cuba via Lima, where we took advantage of the opportunity to see some of the city’s magnificent old colonial buildings with their beautiful balconies. We were anxious to get home, to relate our experiences and especially to be reunited with our partners. Most of us did not want long separations at that time.

The year came to an end, bringing a feeling of satisfaction about what we had accomplished and about the revolution itself. On December 31 we went to the home of our friends Armando Hart and Haydee Santamaría to celebrate New Year’s Eve. Spirits were extremely high that night. Haydee announced she would celebrate her birthday on that date from then on. That night Che danced with Adita, Haydee’s younger sister. To be honest, although he might have wanted to dance, he was a dreadful dancer. He danced in a clownish manner, radiating the joy we all felt. We went home at six in the morning.

The year 1959 had certainly brought about profound changes in our lives. With Che, I felt I was experiencing the best moments of my life—maybe not in the way my romantic novels ended, but I never doubted I belonged with him. Besides, every day I admired him more for his devotion, loyalty and integrity. The more time we spent together, the stronger was the attachment between us.

In a romantic mood, he sent me a postcard from Egypt in 1965, during the last of his extended trips overseas:

Madam,

Through these two doors, solitude escaped and went in search of your green island.

I don’t know if one day we’ll be able to hold hands, surrounded by children, admiring the view from some vestige of the past; if that’s not possible, let it be your dream.

I respectfully kiss your hand,

Your little husband

La Cabaña fortress, Havana, january 1959.

A rest break in La Cabana.

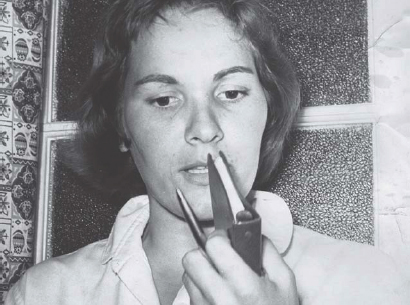

First statements to Bohemia magazine, 1959.

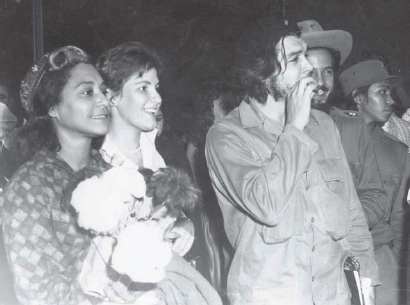

Matanzas, January 7, 1959, where Aleida met Fidel Castro for the first time.

In the Presidential Palace, Havana. (Photo taken by Camilo Cienfuegos.)

Trip to El pedrero with Che‘s parents.

During a 1959 trip to Sumidero, Pinar del Río, in western Cuba.

Che, Aleida (right), Manuel Piñeiro (left) and others in a parade on May 1, 1959, in Santiago de Cuba.

A trip to Minas del Frío, in the Sierra Maestra mountains.

Che and Aleida, with Vilma Espín (wife of Raúl Castro) and Alejandro, the first Soviet ambassador to Havana, during the visit of Soviet Deputy Prime Minister Anastas Mikoyan.

Che and Aleida’s wedding, June 2, 1959. From left, Raúl Castro and his wife Vilma Espín.

Che and Aleida’s wedding, June 2, 1959.

Che and Aleida’s wedding, June 2, 1959.

Che and Aleida’s wedding, June 2, 1959.

Che and Aleida’s wedding, June 2, 1959.

A trip to Bayamo.

Farewell at the airport when Che left on a trip to visit the Bandung Pact (nonaligned) countries, June 12, 1959.

Departure of the Cuban delegation to the Latin American Women’s Congress in Chile. Aleida was a member of that delegation.

Departure of the Cuban delegation to the Latin American Women’s Congress in Chile.

Che and Aleida at a political rally on January 28, 1960.

Aleida with Vilma Espín in Lima, Peru, on their return from the Latin American Women‘s Congress in Chile.

Aleida and Che at a political rally, January 1960.

At the Bellas Artes gallery, 1960.

At an event of the Federation of Cuban Women with Lidia Castro, Calixta Guiteras and Che’s mother Celia de la Serna (right).

Photo taken by Che.

On the way to Baracoa on the Toa River.

Postcard to Aleida sent by Che from Shanghai.

Ciudad Libertad, Havana, with a German delegation, 1960.

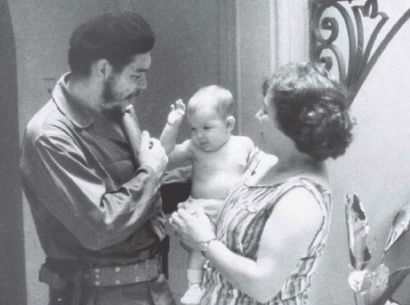

With Aleidita (their first child) in their home in Miramar (1961).

Voluntary work with a Chinese delegation.

Aleida during a 1961 trip to China, as head of a delegation of the Federation of Cuban Women.

During the 1961 Federation of Cuban Women’s trip to China.

During the 1961 Federation of Cuban Women’s trip to China.

During the 1961 Federation of Cuban Women’s trip to China.

During the 1961 Federation of Cuban Women’s trip to China.

Meeting Che at the airport on his return from one of his trips to the Soviet Union.

1. Manuel Piñeiro (Barbarroja or Red Beard) was head of the organization responsible for coordinating Cuba’s assistance to liberation and revolutionary movements in Latin America and elsewhere.

2. Celia Sánchez was a member of the Rebel Army’s general staff and Fidel Castro’s personal assistant).

3. A reference to a popular movie at the time, “Vampires in Havana.”

4. Carlos Rafael Rodríguez was a leader of the Popular Socialist Party (PSP).

5. See Ernesto Che Guevara et al: The Great Debate on Political Economy and Revolution (Ocean Press, 2012).

6. The main revolutionary forces that had opposed the Batista dictatorship were the July 26 Movement, the Revolutionary Directorate and the Popular Socialist Party (PSP). These three organizations fused into the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (ORI) in 1961. Aníbal Escalante, formerly the organization secretary of the PSP, later played a destructive role in the new party.

7. Jorge Ricardo Masetti, an Argentine journalist, was the founder and director of Prensa Latina news agency. He was killed in combat in a guerrilla action in Salta, northern Argentina, in April 1964.

8. This debate is often referred to as the Sierra (mountains) vs the Llano (plains).

9. Camilo Cienfuegos (1932–1959) was a Granma expeditionary. As commander of the Second Column “Antonio Maceo” he led the Rebel Army’s invasion of the northern region of Las Villas, central Cuba. After the revolution, he became head of the Rebel Army, but died in an airplane accident on October 28, 1959.