There are times when words are totally inadequate. It is almost impossible for me now to recall what happened, how Che left and my feelings at the time, partly because I always told myself I would never, ever talk about these things.

I do remember feeling that not only would our relationship change but also that I would never be the same again. When we parted, we assumed that communication would be slow and irregular, but thankfully this was not the case. In the first few months Che was in the Congo, we wrote to each other regularly, and that helped dissipate the uncertainty I felt. There were many compañeros who acted as emissaries, taking and delivering our letters. Osmany Cienfuegos, José Ramón Machado Ventura, Ulíses Estrada, Fernández Mell and Emilio Aragonés were some of those who traveled back and forth from Cuba to the Congo, or who were part of Che’s unit.

These letters remain among my most precious possessions, and reading them shows I wasn’t the only one being tested by our separation. Che, too, experienced great pain. I, at least, had the company of our children, and gained some consolation from them as the testimony of our love.

When I reread these letters now, so many years after they arrived from that distant land of the Congo, I can see the enormous sacrifice it was for Che to leave us behind.

His first letter sent from the Congo began:

To my only one in the world,

(I’ve borrowed this phrase from old Hickmet)1

What miracles you have performed with my poor old shell. I no longer want a real hug and I dream of the concave space in which you comfort me, your smell and your rough rural caresses.

This is another Sierra Maestra, but without the same sense of constructing something or the satisfaction of making it my own. Everything happens very slowly here, as if war was something to be done the day after next. For now, your fear of me being killed is as unfounded as your feelings of jealousy.

My work involves teaching several classes of French every day, learning Swahili and providing medical care. Within a few days I will begin the serious work of training. A sort of Minas del Frio from the war, not the one we visited together.

Give a tender kiss to each child (including Hildita).

Take a photo with all of them and send it to me. Not too big and another little one. Study French in preference to nursing and love me.

A long kiss, like our kiss when we are reunited.

I love you,

Tatu

He used the pseudonym Tatu, meaning “three” in Swahili, during his time in Africa. While I waited for him, I focused on the children, who were all very little, as well as my work in the FMC. I resisted taking any long-term responsibility in the FMC in order to be free to join Che when circumstances permitted.

He constantly expressed his pain at our separation, but asked me not to despair. He urged me to study French so that I could function more effectively if I went to the Congo. Although I tried to fill the void as best I could, I never really came to terms with life without Che.

While he was in the Congo, Che learned of the death of his mother, which affected him deeply, as they had been very close. In a sorrowful letter, he expressed the hope “she had not suffered physically and hopefully she hadn’t had time to think about me.”

He wrote one his most moving stories (“The Stone”) in memory of his mother. In it, he poured out his sense of loss, feeling “a physical need for my mother to be here so that I can rest my head in her bony lap. I need to hear her call me her ‘dear old fella’ with such tenderness, to feel her clumsy hand in my hair, caressing me in strokes, like a rag doll, the tenderness streaming from her eyes and voice, the broken channels no longer bearing it to the extremities. Her hands tremble and touch rather than caress, but the tenderness still flows from them. I feel so good, so small, so strong. There is no need to ask her for forgiveness. She understands everything. This is evident in her words ‘my dear old fella’...”2

This was the man whom some people thought severe. I knew him more intimately. Sometimes he had to show he was firm, although at the same time he could be tender and affectionate.

When I pleaded with him to let me come and join him, he replied:

Don’t try to blackmail me. You can’t come now or in three months’ time. Maybe in a year it will be different and then we’ll see. This has to be properly analyzed. The most important thing is that when you come you aren’t “the little wife” but rather a combatant. You must be prepared for that, at least in French...

A good part of my life has been like that: having to hold back the love I feel for other considerations. That’s why I might be regarded as a mechanical monster. Help me now Aleida, be strong, and don’t create problems that can’t be resolved. When we married, you knew who I was. You must do your part so that the road is easier; there is still a long road ahead.

Love me passionately, but with understanding; my path is laid out and nothing but death will stop me. Don’t feel sad for me; grab hold of life and make the best of it. Some journeys we will be able to take together. What drives me has nothing to do with a casual thirst for adventure and what that entails. I know that, and so should you.[...]

Educate the children. Don’t spoil them or pamper them too much, especially Camilo. Don’t think of abandoning them because it isn’t fair. They are part of us.

I give you a long and sweet embrace,

Your Tatu

Was I as strong as Che wanted me to be? I didn’t know for sure. Sometimes I felt like Dulcinea and at other times like Sancho Panza in my desire to follow the Quixote of modern times, with whom I had chosen to share my life. Like the fictional Quixote, Che was full of tenderness but he never hesitated in challenging new windmills.

I resigned myself to the wait. Events in the Congo, however, took an unexpected turn.3 Despite this, Che tried his best to keep the revolutionary forces intact. He maintained his personal discipline in his application to his intensive study program. He increased the number of books he requested, broadening his reading list. It is extraordinary how, in the midst of all the problems and hardships he experienced in the Congo, and the growing sense of disaster, he continued to study philosophy and other subjects he thought would help him understand better how the Third World could achieve socialism. He constantly asked me for more books; the list speaks for itself. Along with the titles that he requested, he often added comments in brackets:

Hymns Triumphant by Pindar

Tragedies by Aeschylus

Dramas and Tragedies by Sophocles

Dramas and Tragedies by Euripides

Complete Comedies by Aristophanes

The Histories by Herodotus

Greek History by Xenophon

Political Speeches by Demosthenes

Dialogues by Plato

Politics by Aristotle (especially this one)

Parallel Lives by Plutarch

Don Quixote of La Mancha

Complete Works by Racine

The Divine Comedy by Dante

Orlando Furious by Ariosto

Faust by Goethe

Complete Works by Shakespeare

Exercises in Analytical Geometry (from my sanctuary)

Despite his best efforts, the struggle in the Congo came to an unsuccessful conclusion. I received a letter from Che written in Tanzania on November 28, 1965, in which he explained what had happened, how he felt about it and his future plans. He tried to make me see a reunion would be very difficult at that time:

My darling,

Your last letter arrived. Everything turned out differently from what we had expected. Osmany can tell you about the sequence of events. I can only say that my troop made me proud; almost immediately, it became diluted, or rather, melted like lard in a fry pan, escaping from my grasp. I am returning, along the road of defeat, with an army of shadows. Now everything is over and the time has come for the last stage of my journey—the definitive one. Only a handful of select men will come with me—those with stars on their foreheads (the stars of Martí, not military ones).

Our separation was always going to be a long one. I had hoped to be able to see you during what I thought would be a long war, but it wasn’t possible. Now there will be a lot of hostile territory between us, and communication will be less frequent. I can’t see you before I leave because I must avoid all possibility of being detected. In the mountains I felt secure, with my weapon in my hand, but I don’t feel in my element in clandestinity. I have to be extra cautious.

Now comes the truly difficult time for everyone, and we must be prepared to bear it. I hope you know how. You must bear your cross with revolutionary fervor. If I reach my destination, and when they realize it, they will do everything to destroy us. Our security measures will then need to be even more rigid, and we will have to accept a greater isolation. I will always find ways to get a few lines to you; but if I can’t, please don’t imagine the worst. I will regain my spirits once I reach my destination, even though there will be problems at first.

It is hard for me to write this. The technical details are of no interest and memories of a past life will take time to recover. You know I’m a combination of adventurer and bourgeois, with a terrible yearning to come home, while at the same time, anxious to realize my dreams. When I was in my bureaucratic cave, I dreamed of doing what I have begun to do. Now, and for the rest of my journey, I will dream of you, while the children inevitably grow up. They must have such a strange vision of me. How difficult it will be for them one day to love me like a father and not regard me as some distant monster they are obliged to love.

When I leave, I will leave you some books and notes, please keep them. I have become so accustomed to reading and studying, it is now second nature to me—a great contrast to my adventurous spirit. As always, I wrote you a little verse and, as always, I tore it up. I am a better critic and I don’t want accidents like the last time. Now that I am a prisoner, with no enemies nearby, or injustices in my sights, my need for you is virulent and physiological, and cannot always be calmed by Karl Marx or Vladimir Ilyich.

Give the birthday girl a special kiss. I haven’t sent her anything because it is better for me to disappear altogether. I saw you standing on a platform; you looked really great, almost like in the good old days of Santa Clara. I, too, was almost restored to my former self, but now I am once again the insignificant Bald Samson.

Educate the children. I always worry about the boys, in particular. Tell the old man to visit them. Give a big hug to the good old folks you have there and receive an embrace yourself—not the last one, but with all my love and the desperation as if it was our last embrace.

A kiss,

Ramón

At this time, Fidel, who was always checking on our family, invited me to participate at the first graduation ceremony of doctors after the revolution. This was held at Turquino, the highest mountain in Cuba, situated in the Sierra Maestra.

The symbolism of the place was very strong, and many important events were held there. On arrival, we saw Sergio del Valle, an aide-de-camp and doctor in Camilo Cienfuegos’s Second Column, who was then chief of staff of the armed forces. He had come to tell Fidel about the withdrawal of Che’s troop from the Congo, which Che explained in greater detail in his letter to Fidel. Che wrote a comprehensive analysis of the experience in the Congo while he was in Tanzania, based on the diary he had kept. This has now been published as Congo Diary: Episodes of the Revolutionary War in the Congo. As soon as we knew the Cubans had withdrawn from the Congo, Fidel gave me permission to go and see Che. He acted as mediator between us as he had done in the past. I fervently hoped Che wouldn’t resist, and to my delight, this time he didn’t. My trip to Tanzania was confirmed in December 1965, making me extraordinarily happy. As I prepared for my departure, I decided this was the most eagerly awaited New Year celebration of my life.

Sometime around January 15, 1966, I landed in Prague. I stayed in an apartment that would later be used by Che and other compañeros while they prepared for their Latin America mission. I had traveled with Juan Carretero (Ariel), a compañero from the department of the Cuban Communist Party, headed by the legendary “Red Beard” (Manual Piñeiro), one of the key coordinators of Cuba’s links with the revolutionary movements in Latin America. From Prague, we traveled to Cairo and then on to Tanzania.

Che was waiting for me there, transformed into another character I almost didn’t recognize. He was clean shaven, not wearing the olive green uniform he always wore in Cuba. I, too, was incognito, extremely nervous, full of doubts. But all that vanished as soon as I recognized him and we were together again.

In order to travel, I had disguised myself with a black wig and glasses that made me look much older than I was. So two apparent strangers met in Tanzania, but our feelings for each other could not be disguised.

For a short time, we were able to be completely alone. Our solitary confinement was necessary for security reasons, but we couldn’t have been happier. I had a chance to look around the city briefly when I arrived and again when I left. Our accommodation was not particularly comfortable, but that hardly mattered. We had a single room in which we slept, ate and studied, and a bathroom, where Che developed some of the photographs he had taken with his professional quality camera. We also returned to our regular routine. After breakfast, I would read, always with Che’s guidance, and he would read or write. He also gave me French lessons, and I made some progress.

During this time in Tanzania he recorded himself reading stories for the children. These recordings became some of their most valued possessions. He also wrote Fidel a letter, asking me to deliver it. This was an analysis of the liberation movement in Guatemala.

We discussed many things. I remember his comments about his farewell letter to Fidel, and how important it was to him. He was clear, wherever he went to fight after the Congo, that he would always regard himself as representing the Cuban revolution, symbolized in the battle-cry: “Hasta la victoria siempre! Patria o muerte!” [Until victory, always! Homeland or death!]

Not everything was serious, of course. We reminisced about happy times and things we had experienced in our lives together. We also cleared up a few past misunderstandings, including the incident in the INRA office with the disappearing secretary. He said he had always thought I had asked her to leave because her role was superfluous, as I took care of all his personal affairs. Every time we had discussed this before, I denied my role. But now, after six years, I finally confessed. I explained it was not because I was jealous, or that I had a bad opinion of the young woman, but because, from a political point of view, I didn’t believe she was up to the task of being Che’s secretary. Che was satisfied with this explanation.

We discussed our friends, for example what had happened to my friend Lolita Rosell, to whom I had been close during our time in the underground struggle. After the revolution, Lolita became president of the FMC in Las Villas. She had some difficulties in her province with the sectarian faction in the party, led by Aníbal Escalante. She requested a meeting with Che to discuss this. He agreed on the condition that a number of others also attend the meeting. These were: Emilio Aragones, a member of the PURS4 and the head of the army in Las Villas; William Gálvez and a leader of the former PSP, compañero Luzardo, who was then Minister of Interior Commerce. I never heard about what had happened at that meeting, but Lolita told me she was happy with the outcome. In Tanzania, Che told me how Lolita had shown great integrity and courage. After that meeting, Che asked her to come to Havana to work in the newly created Ministry of the Sugar Industry.

Che’s next plans were becoming urgent. In spite of what had happened in the Congo, he still intended to proceed with his plan to extend the struggle for the liberation of Latin America, following in the footsteps of Simón Bolívar and José Martí.

I don’t quite remember when he left for Prague—maybe my mind refused to register it—but I think it was in the first few weeks of March. I found myself alone in the little room that had been our refuge. I was devastated, and not even reading distracted me. I hardly understood what I was reading.

Maybe I should have written down my thoughts but I couldn’t. I feared I would never see Che again, or maybe not for many years. I knew that I had to get used to the idea and live with the feeling that it might have been our last time together. We had several separations like this, and each time felt like it was final.

I always expected my life to be full of anxiety and uncertainty. This time, after experiencing such peace and pleasure at being reunited, I dreaded to think I might never hear from Che again. While he had been in the Congo we were able to communicate once a month. But now?

I returned to Cuba having been away for a month and half. I traveled from Cairo to Moscow with Oscar Fernández Padilla. My despairing mood was somewhat brightened when I was reunited with my children and able to give them the special gift of the tape-recorded stories read by their father.

A few days later Fidel’s office called, asking me to pick up a small notebook Che had sent me along with some personal notes. One of the pieces in the notebook was titled “Delivery,” reflecting the sadness and certainty he felt at the prospect we would not see each other for a long time:

My love,

The moment has come to send you a farewell tasting of earth (dry leaves, something far away and disused). I wanted to do this with lines that don’t reach the margins—often called poems—but I have failed.

There are so many intimate things for your ears only that words cannot express, only the shy algorithms that amuse my breaking wave. The noble trade of poet is not for me. It isn’t that I don’t have sweet things to say. If you only knew what is contained there in a whirl inside me. But the shell that contains them is too long, convoluted and narrow.

They emerge, exhausted from the journey, and in a bad mood, elusive; the sweetest ones are the most fragile and are left behind, shattered, disparate vibrations...

I’m a useless medium. I would disintegrate trying to convey everything at once. Let’s use everyday words to capture the moment.

[...] That is how I love you, remembering the bitter coffee every morning, the taste of the dimple in your knee, the ash of a cigar delicately balanced, the incoherent grumbling with which you defend your impregnable pillow.[...]

That is how I love you, watching the children grow, like a staircase with no history (and I suffer because I can’t witness those steps). Every day, it’s like a stabbing in my side, upbraiding the idler from its shell.

This will be a real farewell. Five years in the mire have aged me. Now there remains only one last step—the definitive one.

The siren songs have ended, and so has my inner conflict. Now the flag is raised for my last race. The speed will be such that screams will accompany me. The past has come to an end; I am the future in progress.

Don’t call me, because I won’t be able to hear you. But I will sense you on sunny days, under the renewed caress of bullets. [...]

I will keep a look out for you, in the way a dog remains alert while it’s resting, and I will imagine every part of you, piece by piece, and altogether.

If one day you feel the force of an overbearing presence, don’t turn around, don’t break the spell, just keep on preparing my coffee, and let me experience you in that instant, for always.

It so happened that fortune smiled on us again. After my constant complaints and Che’s continued resistance, in April 1966 we were reunited in Prague. In this undated letter, he wrote:

Two letters. It isn’t true that I don’t want to see you and I have not run away [...].

I came here to get things going and that is what has happened to some extent. I didn’t think it was appropriate for you to come. You might have been detected (by the Czechs or our enemies). Your absence from Cuba would be noticed immediately. Moreover, travel is expensive and this upsets me. If Fidel wants you to come, then that’s up to him (he can weigh up the factors) and he can decide[...].

Prague was an enchanting city; but the fact that we didn’t have much of an opportunity to enjoy it fully didn’t matter to us. We had to maintain strict discipline, functioning in absolute secrecy. It was enough for us to simply be together again.

We stayed in two places in that beautiful city: one was the apartment I had stayed in on my way to Tanzania. It was quite small, with only one room with a bed, and a bathroom that was also used as a kitchen and laundry. We stayed there for a week.

Then we moved to a large, comfortable country house. The owner lived there with her daughter, who had an intellectual disability. They cooked for us and we were there with other compañeros who were preparing to go to Bolivia with Che. These were Alberto Fernández Montes de Oca (Pacho), Harry Villegas (Pombo) and Carlos Coello (Tuma) and others, who visited for work reasons.

At night we played canasta to entertain ourselves. I didn’t particularly enjoy those card games because I always lost. Che would try to help me—whenever I was in a tight spot he came to my rescue. He was the same when we had target practice. He would stand behind me to correct my stance, never allowing me to look bad in any situation where I was being tested. This was his way of showing me his affection and support.

I could only ever manage to beat Coello in target practice. He was less dexterous than I was and a terrible shot. We enjoyed his jokes and his cheerful personality. We were all very fond of him. I would joke with him, saying I would take his place in the next struggle, repeating this often to see if anyone was paying attention.

If the day was fine, we would go on walks through a nearby pine forest; at weekends, we would return to the city at night with José Luis Ojalvo, the compañero who looked after us in Prague.

On odd occasions, we would break the rules and escape. Once we went to eat at a restaurant close to the apartment, and an amusing incident occurred. We generally ordered beef steak, and Che would put on his best Czech accent. But on that occasion, we wanted to try something different. Confident of his ability in French, Che ordered for us. We were very surprised when the waiter brought us “bistec anglisqui”—what we always ordered. We laughed so much at the waiter’s perfect French. We were happy, enjoying our time alone together and our adventures with the others. Once we went to a stadium to watch a game of soccer.

I especially remember a day trip we made to a rural area. On our return we stayed in a small, very friendly motel. There, we let ourselves dream a bit, making plans to return some day. But this was never possible. Yet again we had to forego our small pleasures. Similarly, we never got to see Karlovy Vary, a beautiful spa town Che very much wanted us to visit together.

At the end of May we learned of a possible attack on Cuba by the United States, following the assassination of one of our soldiers guarding the Guantánamo Naval Base, territory usurped by the United States from the time of Cuba’s so-called independence in 1902.

Due to the seriousness of the situation, Che brought forward the date of my departure, originally scheduled for June 2, the date of our wedding anniversary. I would be lying if I said I was happy to return. But of course I wanted to be with my children and had little choice in the matter. Che decided, in the case of a US attack against Cuba, he would return to Cuba to fight alongside his people.

The day before I left, I went to a store and bought him some cuff links to surprise him. They were quite small, and I knew he would always be able to carry them with him; and I believe he did, because no one has ever returned them to me. (It’s possible someone has held onto them as a war trophy.) He never knew the cuff links were a gift from me until he returned to Cuba in July 1966 to train the group that would go to Bolivia. He was then overjoyed.

Che had not considered returning to Cuba after the Congo mission. Again, he was convinced by Fidel’s great power of persuasion. Fidel wrote to Che in Prague, arguing that Cuba was the best place to complete the final phase of the training for Bolivia, assuring him of his total discretion:

Events have overtaken my plans for a letter [...]

It seems to me, given the delicate and worrying situation in which you find yourself there, that you should consider the usefulness of jumping back here.

I am well aware that you are especially reluctant to consider any option that involves a return to Cuba for the moment, unless it is in the quite exceptional circumstances mentioned above.

But analyzed in a sober and objective way, this actually hinders your objectives; worse, it puts them at risk. I find it very hard to accept the idea that this is right, or even that it can be justified from a revolutionary point of view. Your time at the so-called halfway point increases the risks; it makes extraordinarily more difficult the practical tasks that need to be carried out; and far from accelerating the plans, it delays their fulfillment; moreover, it subjects you to a period of unnecessarily anxious, uncertain and impatient waiting.

What can be the point of that? There is no question of principle, honor or revolutionary morality involved here that would prevent you from making effective and thorough use of facilities that you can certainly depend on to achieve your goal. No fraud, no deception, no tricking of the people of Cuba or the world is involved in making use of the objective advantages of being able to enter and leave here, to plan and coordinate, to select and train cadres, and to do everything from here that you can achieve only with great difficulty from where you are or somewhere similar. Neither today nor tomorrow, nor at any time in the future, could anyone consider it wrong—nor should you in all conscience. What would really be a grave, unforgivable error is to do things badly when they could be done well; to have a failure when all the possibilities are there for success.

I am not insinuating, not in the least, that you abandon or postpone your plans, nor am I letting myself be carried away by pessimistic considerations due to the difficulties that have arisen. On the contrary, the difficulties can be overcome, and more than ever we can count on having the experience, the conviction and the means to carry out those plans successfully. That is why I think we should make the best and most rational use of the knowledge, the resources and the facilities that we have at our disposal. Since first hatching your now old idea of further action in another setting, have you ever really had enough time to devote yourself entirely to this matter, to conceiving, organizing and executing your plans to the greatest possible extent? [...]

It is a huge advantage for you to be able to use what we have here, to have access to houses, isolated farms, mountains, cays and everything essential to organize and personally lead the project, devoting 100 percent of your time to this and drawing on the help of as many others as necessary, with only a very small number of people knowing your whereabouts. You know perfectly well that you can count on these facilities, that there is not the slightest possibility that you will encounter problems or interference for reasons of state or politics. The most difficult thing of all—the official disassociation—has already been done, not without paying a price in the form of slander, intrigues, etc. Is it right that we should not extract the maximum benefit from it? Has any revolutionary ever had such ideal conditions to fulfill their mission, and at a time when that mission acquires great importance for humanity, when the most crucial and decisive struggle for the victory of the peoples is breaking out? [...]

Why not do things well if we have every chance to do so? Why don’t we take the minimum time necessary, even while working at the greatest speed? [...]

I hope these lines won’t annoy or upset you. I know that if you analyze what I say seriously, your characteristic honesty will lead you to accept that I am right. But even if you come to a completely different decision, I won’t feel disappointed. I write to you with deep affection and the greatest and most sincere admiration for your brilliant and noble intelligence, your irreproachable conduct and your unyielding character of a whole-hearted revolutionary. The fact that you might see things differently won’t change these feelings one iota nor affect our collaboration in any way.5

I have always regarded this letter as testimony to the incredible bond of loyalty and respect that existed between these two men, two intransigent guerrilla fighters—an eloquent answer to the many lies and slanders spread about them.

I received a brief note from Che addressed to my nom de guerre. He reproached me for tearing out the page of his copy of El Ciervo on which the author, the Spanish poet León Felipe had written a dedication to him:

Josephine, my love,

I will soon experience another warm and salty shower, related to my clandestine status.6

You have mutilated my copy of El Ciervo and I cannot forgive you. If I get the chance, I’ll take my revenge.

A warm kiss, because it is very new and full of hope. Another big one for the children.

Your Ramón

Che returned to Cuba around the time of the July 26 celebrations when many visitors were arriving at the airport, making it less likely he would be identified by journalists. But as always there was a slight hitch. When he arrived, Santiago Alvarez had a crew filming the arrival of various celebrities. Two compañeros from Piñeiro’s office, Juan Carretero and Armando Campos, had to intervene and go to ICAIC to ensure that the film was destroyed.

Many years later, Santiago, a well-known documentary film maker, enjoyed narrating the story of how the two men had come to his studio and asked to see the film shot at the airport. With so many reels of film to watch, the search took a very long time. Moreover, poor Santiago didn’t know what they were looking for. Eventually, they found the images of Che in disguise, and those sections were cut from the reel. This remained a secret for decades.

In my view, this was probably unnecessary, because Che was totally unrecognizable. Before leaving Prague, he put on thick glasses and padding around his body, which made him look corpulent and slightly hunched over; he generally appeared much older than he was.

I can’t remember if it was that same day that Celia Sánchez called to tell me she would pick me up in a few minutes. If I wanted to, she said, I could bring Ernesto with me, our youngest child, whom Che had hardly had a chance to get to know. He was only one month old when Che left for the Congo. I didn’t need to be told where I was going.

I collected a few essential items while I waited for Celia to pick me up in her car. This was my first visit to San Andrés de Caiguanabo in Pinar del Río, an extraordinarily beautiful place Fidel had selected for the training of the small group of combatants that would accompany Che to Bolivia.

I had to return home the next day, because my prolonged absence would provoke rumors or questions. I was told I could return whenever circumstances allowed. At this point, it was critical that nothing should get in the way of the plans.

None of that worried me, of course, and I enjoyed our clandestine encounters. The most important thing for me was to have him nearby, away from danger and among compañeros and friends, beyond the reach of an enemy bullet or a breach of security that would undermine his project.

I traveled to see him whenever I could. Sometimes I stayed a bit longer, and Che allowed me to take part in the training exercises with the other compañeros. We went for long hikes in the strong sun; the men would be encumbered with their backpacks and weapons, and I would be as free as the wind, following Che as in the old days.

Sometimes we would compete with the rest of the group to see who arrived back first at the starting point. Che usually walked slowly, but without stopping to rest, and if we did stop, we did not sit down. In that way, we left many compañeros behind.

In August, I took little Celia with me. She was only three years old and was sick with a sore throat. Che was delighted to see her and enjoyed playing with her, even though she was unaware she was with her father. We took some beautiful photographs that day. In the last letter he wrote to the children, sent for Aliucha’s birthday, he wrote, “Celita, help your grandmother around the house and stay as lovely as you were when we said good-bye, do you remember? I bet you do.”

On one of our hikes in the mountains of Pinar del Río, as we descended a cliff, the rock I was holding onto came away and I fell backwards, landing about half a meter from the edge. Che quickly came to my rescue. Luckily, I only sustained a few scratches and we continued on our way, arriving back before the rest of the group. When they passed the spot where the accident had occurred and saw blood stains on the rocks, the compañeros became concerned. But they started joking around when they found us sitting waiting for them.

On another occasion, we went out at sunset on horseback with some compañeros. My horse suddenly slipped and I found myself hanging from a small tree, very close to a precipice. Somehow, the horse fell into the ravine. When he saw what had happened, Che had to rescue me again. He checked that I wasn’t injured, except for some scratches and torn pants, and went off to rescue the horse. I returned to the house on his horse.

To test the effectiveness of his transformation into “Ramón,”7 Che went to visit a group of his former soldiers. I wasn’t allowed to go with him, because they might then guess the identity of the stranger. So I stayed hidden behind a window in order to watch their reactions. Che was introduced as a Spanish instructor, a friend of Cuba. No one recognized him, even though he told some jokes, until one of them, Jesús Suárez Gayol, realized it was indeed Che.

Their faces reflected the euphoria they experienced, knowing that the troop would be led by their leader. It was a small, select group, many of whom had faithfully collaborated with Che, not only in war but also in the greater struggle, which was the construction of a new society. Some, like Octavio de la Concepción de la Pedraja (Moro) and Israel Zayas (Braulio) had been with Che in the Congo. Others, including José M. Martínez Tamayo (Papi), Harry Villegas (Pombo) and Carlos Coello (Tuma), were already in La Paz, preparing conditions for the arrival of the rest of group, those “with stars on their foreheads,” as Che described these most dedicated and courageous men.8

While the training proceeded in San Andrés, I sometimes cooked for the entire group and this brought everyone together as a happy family. A bit of affection and unity are always important in such moments. I particularly recall Moro. He was a little overweight and trying to diet; sometimes he would only get popcorn to eat. But when he saw the others feasting on what I had prepared, he abandoned his diet and ignored the many jokes made at his expense.

On some nights, when we weren’t too tired, we watched movies—usually westerns, because that’s what everyone liked. Those gatherings were often marred by the presence of hundreds of little frogs. I have always had an irrational fear of frogs. One time, one of them landed on my leg and Vilo Acuna (Joaquín) heroically came to my aid. It is strange how in extreme circumstances, we can overcome our fears. During my time as a guerrilla in the Escambray Mountains and in the actual training sessions at Pinar del Río, I was never bothered by those little animals.

A select group of compañeros came to visit at the farm. I remember Armando Hart sitting at the dinner table with Che for hours, discussing philosophy or arguing about Sigmund Freud’s theories. These discussions were prompted by Che’s letter to Armando (Minister for Education) in December 1965, in which he outlined a study guide on Marxism:

My dear secretary,

My congratulations for the opportunity they have given you to be God: you have six days.9

Before you finish and sit down to rest (unless you choose the wise road of the God before you, who rested earlier), I want to propose a few small ideas about developing the culture of our vanguard and our people in general.

In this long vacation period I have had my nose buried in philosophy, something I have wanted to do for some time. I came across the first problem: nothing is published in Cuba, if we exclude the hefty Soviet manuals, which have the drawback of not allowing you to think for yourself, because the party has already done it for you, and you just have to digest it. In terms of methodology, it is as anti-Marxist as can be and, moreover, the books tend to be very bad.

Second, and no less important, was my ignorance of philosophical language (I fought hard with Master Hegel, and in the first round bit the dust twice). So I made a study plan for myself, which I think could be looked at and improved a lot, but it might constitute the basis for a real school of thought. We have achieved a lot, but someday we will have to think for ourselves. My idea is a reading plan, naturally, but it could be expanded to bringing our serious works into the party publishing house.

[...]

This is a gigantic job, but Cuba deserves it, and I think it can be attempted. I won’t bother you any further with this chatter. I’ve written to you because I don’t know much about the people who are presently responsible for ideological work and it may not be prudent to write to them, for other reasons (not just ideological parrotry, which also counts).

Okay, illustrious colleague (in the philosophical sense), I wish you success. I hope we can meet on the seventh day. A hug to the huggables, including one from me to your dear and feisty better half.10

R.11

The days of preparing for Bolivia were coming to an end, and this time I resisted Che’s departure less, perhaps because I had participated in some of the activities and also because I imagined a reunion would not be too far off. I expected a long struggle, and I thought we might face five years of separation, but I firmly believed we would be reunited again. That is how I thought when Che left for Bolivia in October 1966.

Over the years, I have always dreaded the advent of the month of October because for Cubans, and for me in particular, this month does not bring good memories, and to describe my feelings is almost impossible.

When everything was ready for Bolivia, I asked, as I had done when he left for the Congo, if he should not stay for another year to complete some tasks that he had previously been assigned. But nothing would detain him. He was convinced that the pillars of the Cuban revolution were strong and he didn’t believe his presence in Cuba was essential. In Latin America, however, he saw there was much to be done, and he was eager to contribute to eliminating the evils that had prevailed there for centuries.

A few days before Che’s departure, with him now transformed into the old man “Ramón,” we went to a safe house in Havana, where he asked to see the children. It had to be that way because he feared that our older children might tell someone if they recognized him, and this could be a serious problem.

When the children arrived, I introduced them to a man I said was a Uruguayan friend of their father and who wanted to meet them. They could never have imagined that this man, who looked as though he was in his 60s, was their father. It was a difficult moment for us both, especially painful for Che because he loved his children but could not say much or treat them in the way he wanted to. This was one of the hardest tests he ever had to undergo.

For the children, it was a most enjoyable day. They played and did their best to amuse their father’s friend. They wanted to show him all the clever things they could do, even playing the piano for him, although it sounded more like banging to me. While she was running about, Aleidita, the eldest, hit her head, and Che went over to tend to her. He treated her so tenderly that, a little while later, she came up to me to tell me a secret: “Mommy, that man is in love with me!” Che heard her whisper to me. Neither of us could speak; we just became pale, overwhelmed by emotion.

He left for the airport from that house. He traveled first to Europe and then proceeded to his final destination, La Paz, Bolivia. Before he left, he wrote me a poem that I was told he wanted to write on a white handkerchief, but he couldn’t find one. The important thing is this time he did not tear up his poem, and he finally finished what he had long promised me. I hardly need to say I treasure this poem as one of the most cherished mementos Che left me. The final stanza reads:

Farewell, my only one,

do not tremble before the hungry wolves

nor in the cold steppes of absence;

I take you with me in my heart

and we will continue together until the road vanishes...

I wondered if we would experience yet another cycle of separation and reunion. I cried so much on the way home. I remember that I looked over some articles of clothing of Eliseo Reyes (Rolando) with the aim of removing any tags that could identify him as Cuban in preparing for his departure for Bolivia. I was searching for anything to do to ease my anguish. I had to get on and face life until I heard any news.

Once again there was uncertainty. News from Bolivia always came through a third person. The only letter I received was via the Peruvian Juan Pablo Chang (Chino), after his visit to the Ñancahuasú camp on December 2, 1966, and before he joined the guerrilla unit:

To my only one,

I take advantage of a friend’s trip to send you these words. They could be posted, but it is more intimate to use the “unofficial” route. I could say that I miss you to the point where I can no longer sleep, but I know you wouldn’t believe me, so I won’t tell you that. There are days when I feel so homesick, it takes a complete hold over me. Especially at Christmas and New Year, you can’t imagine how much I miss your ritual tears, under a star-filled sky that reminds me how little I have taken from life in a personal sense [...].

I can say nothing interesting about my life here. I like the work but it is tiring and excludes all else. I study when I have time, and occasionally I dream. I play chess with no serious opponents and I walk a great deal. I am losing weight, partly from longing, and partly from the work.

Give a kiss to the little pieces of my flesh and blood and to the others. For you, a kiss filled with sighs and sorrow from your poor, bald

Husband

In general, that was the tone of his correspondence, which was infrequent and offering few details, although he was usually optimistic about the prospects of the ELN (the National Liberation Army of Bolivia). In a way he was right to be optimistic; I later heard about the courageous actions they had carried out as a small group of combatants facing a better-equipped army with more men. It was this optimism that never allowed me to contemplate the final outcome.

Meanwhile, my life carried on as usual; the security garrison was now smaller, but was still next door to our house. Occasionally, Fidel would become worried about us and pay us a visit, always mindful of our needs. In fact, when Che wrote his “Message to the Tricontinental,” Fidel brought the document to my house to tell me what he thought of it. This was not really necessary, but that is how Fidel was with everything concerning Che. He never failed to update me on the progress of the guerrilla movement in Bolivia.

My commitments had changed somewhat. Before leaving for Bolivia, Che urged me to enroll at the university to study history, which I did in November 1966, and I must admit that he was not wrong. This proved to be a wise decision because I now used part of my time to study, clinging to it almost as a shipwrecked sailor clutches at his salvation.

I made a big effort, and took advantage of the opportunity I was presented with. I was studying with younger people, with the exception of María Luisa Rodríguez, who was older than me, and she became my study partner. She was very organized and capable; she was also the head of her household and didn’t want to stay at home. Despite her wealthy background and her privileged life, she responded like all Cuban women did to the demands of the times.

I studied with enthusiasm and tried to adapt myself to a study routine. Compared to the other students, I had far more life experience, but it was difficult for me to concentrate on my studies. My classmates and teachers helped me, showing me great kindness in a situation new to me. I was grateful to Che for encouraging me to step into a very different world and out of the isolation of my own little world.

The month of October came around again. I heard the terrible news from Fidel. He waited until the report from Bolivia had been verified. At the time, I was involved in some important research work in the Escambray Mountains as a history student.

Celia Sánchez traveled to Santa Clara, and from the airport she organized for me to be picked up and taken directly to Havana, where Fidel was waiting for me. He took me to his house, where I stayed on my own for one week. I then went to stay in another house for a while with my children. Fidel visited us every day. I can never forget the kindness and dedication he showed us during those days. He gave us so much of his time and helped to ease our pain. Appreciating his tenderness, I was aware that he, too, was deeply mourning the irreparable loss that Che’s passing represented.

Since that time, in spite of the fact I don’t see Fidel regularly because of the immense responsibilities he has borne, nothing has ever marred our mutual affection and the solid basis of our friendship. Everyone acknowledges the debt we Cubans owe him, but my debt is far greater on a personal level.

On October 18, 1967, a solemn vigil for Che was held in Revolution Plaza. Fidel was the only speaker. He asked me to be there, but I told him I didn’t have the strength to behave with the composure demanded of me in such a ceremony. I told him I would stay at home, watching the event on television, surrounded by my children, although they were not yet aware of what had happened.

The vigil in the plaza was a moving event for our people. I had never seen so much sadness reflected in the faces of the men and women, who came to the plaza in absolute silence to pay homage to the legendary guerrilla, the brother they had always felt was one of their own.

I returned to my own home in November, accompanied by my offspring, who were noisy and restless and allowed me little time to become absorbed in my grief. I had to get on with life, I had things to do. But there were the inevitable moments when I would hear the verses of the poem he had written for me:

My only one in the world:

I secretly extracted from Hickmet’s poems this sole romantic verse, to leave you with the exact dimension of my affection.

Nevertheless,

in the deepest labyrinth of the taciturn shell,

the poles of my spirit are united and repelled:

You and EVERYONE.

Everyone demands complete devotion from me

so that my lonely shadow fades on the road.

But, without ridiculing the rules of sublime love,

I hide you in my saddlebags.

(I carry you in my insatiable saddlebags, like our daily bread.)

I leave to build the springs of blood and mortar

and I leave in the vacuum of my absence

this kiss with no fixed address.

But the reserved seat was not assured

in the triumphant march of victory,

and the path that guides my travels

is overcast by ominous shadows.

If my destiny is an obscure seat of honor in the foundations,

just place it in the hazy archive of your memory,

to use during nights of tears and dreams...

Farewell, my only one,

do not tremble before the hungry wolves

nor in the cold steppes of absence;

I take you with me in my heart

and we will continue together until the road vanishes...

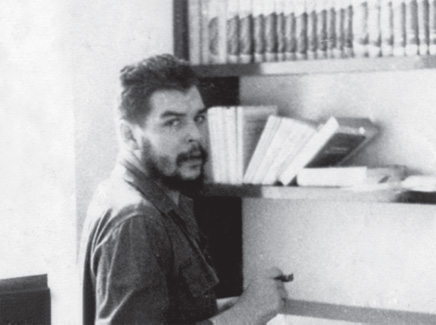

Che and Aleida during a trip around the Cuban provinces, 1959.

Aleida and Che organizing their office in their Nuevo Vedado home, 1963.

With Camilo, Che and Aleida’s first-born son.

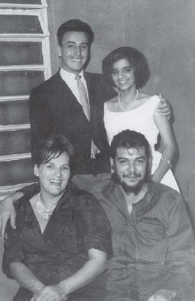

At the wedding of Aleida’s niece Miriam Moya March, 1965.

With Ernestico (Ernestio) their second son, in 1965.

With Celia, their third child, in 1964.

February 1965, with the newborn Ernesto.

With Fidel at a 1965 ceremony in Revolution Plaza.

Almendares Park, December 1964. Left to right: Camilo, Celia, Aleida and Aleidita.

March 1965, in front of their house in Nuevo Vedado, Havana, before Che left for the Congo. Children (from left): Ernesto, Camilo, Aleidita and Celia.

July 1965. From left: Aleida and Ernesto, Camilo, Hildita (Che’s daughter with Hilda Gadea) and Aleidita.

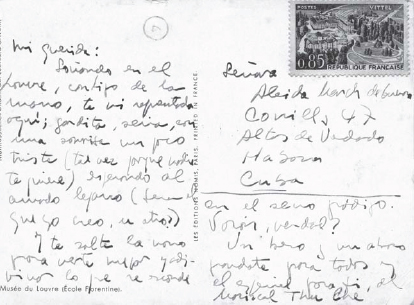

A postcard with a portrait of Lucrecia Crivelli, Che sent to Aleida from the Louvre Museum, Paris, in 1965.

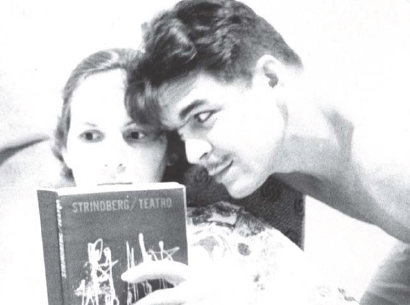

This 1965 family photo was sent to Che in the Congo.

Aleida with Fidel and Rosa E. Navarro at the end of 1965 at Turquino Peak, in the Sierra Maestra mountains.

Lunch at the home of Cuban Foreign Minister Raúl Roa (left).

January 1966: Aleida and Che disguised as Josefina and Romón, during their meeting in Tanzania after Che had been in the Cango, Africa. (Photos taken by Che.)

Aleida with Che in tanzania. (photo taken by Che.)

Tanzania. (Photo taken by Che.)

Aleida’s passport photo as Josefina González, January 1966.

The children with Che disguised as “old uncle Ramón” in Havana, October 1966, before he left for Bolivia.

Che, Aleida and their daughter Celia in San Andrés, Pinar del Río, 1966. (Photo taken by Che.)

Aleida with Celia, 1966. (Photo taken by Che.)

Che with Celia in San Andrés, Pinar del Río, 1966.

A rest break during training for Bolivia in San Andrés, Pinar del Río, 1966. (Photo taken by Che.)

With Che disguised as “old uncle Ramon” a few days before he left for Bolivia in 1966.

Family photo taken by Korda in May 1965. Children (from left to right): Hildita (Che’s daughter with Hilda Gadea), Aleidita, Camilo, baby Ernesto and Celia.

Aleida with the children, 1966.

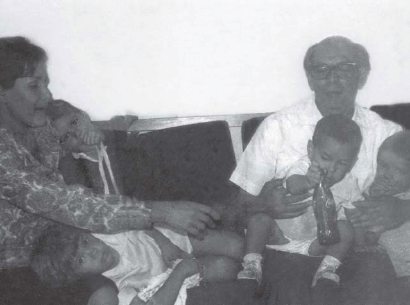

The children with their grandparents Juan and Eudoxia on Ernesto’s birthday, February 1968

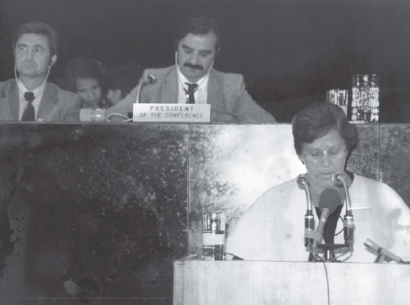

Aleida as a Cuban representative of the Inter-Parliamentary Group.

The children with their grandmother Eudoxia (Aleida’s mother).

Aleida with Fidel at Aleidita’s wedding.

Aleida with her friend Ernestina Mazón, her daughter Aleidita and some of her grandchildren.

Daughter Celia’s wedding.

Che and Aleida in Santiago de las Vegas, Cuba, 1959.

1. The Turkish poet Nazim Hickmet was one of Che’s favorite poets.

2. Che’s short story, “The Stone,” is included as an appendix to this book.

3. See Ernesto Che Guevara: Congo Diary. Episodes of the Revolutionary War in the Congo (Ocean Press, 2011).

4. The United Party of Socialist Revolution (PURS) developed out of the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (ORI). It was the forerunner of the Cuban Communist Party that was formed in 1965.

5. For the full text of this letter, see Ernesto Che Guevara: Congo Diary. Episodes of the Revolutionary War in the Congo (Ocean Press, 2011).

6. A reference to the fact that Che was expecting to return to Cuba.

7. Che disguised himself as an older man and used a passport in the name of Ramón Benítez for his clandestine trip to Bolivia to initiate the guerrilla struggle in Latin America.

8. Of all the Cubans who joined Che in Bolivia, only Harry Villegas and two others survived.

9. Armando Hart had just been appointed organization secretary of the newly formed Cuban Communist Party.

10. Haydee Santamaría was Armando Hart’s wife.

11. The full text of this letter is included in Ernesto Che Guevara: Self-Portrait (Ocean Press, 2004).