CHAPTER 6 VILLAGE INDIA

‘The villages are the cradle of [Indian] life and if we do not give them what is due to them, then we commit suicide.’

Rabindranath Tagore, great Indian poet

AS THE RELIGIOUS festival periods arrive through the year, streams of bright-green buses pour out of Indian cities such as Mumbai and Surat to hum onto the Golden Quadrilateral highway that now forges a high speed link right across the country. Every bus is packed solid with city workers, taking a brief respite from work in the city to return to their families in villages far away across India. The Golden Quadrilateral was intended mainly to speed business travel between India’s big four cities – Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata and Chennai. But it is beginning to open India up to another kind of traveller – the rural migrant worker, and the rural commuter.

Every month, more and more Indian villagers are getting on the bus and heading into the cities in the hunt for work. Often the distances they travel are huge. Poor farmers from Orissa, for instance, might travel nearly a thousand miles to Surat to get a job in the burgeoning textile and diamond industries there. Some of them will stay a short while. Others end up never going back. And the cities on Quadrilateral – cities such as Kanpur and Surat, as well as the big four – are sucking them in as they trawl for cheap, short-term labour to supply their industries.

Metro campers

Commentators have sometimes underestimated the pull of the cities for India’s rural poor. They look at the pace of urbanisation in countries such as China and India, and observe that India’s urban growth has been surprisingly sluggish. Between 1981 and 2001, the census years, the proportion of India’s population living in cities went up from 23.7 per cent to just 27.8 per cent. This is not quite what you’d expect from a rapidly growing economy. Even some European countries are urbanising as fast. But these simple figures disguise the real lure of India’s cities.

The main reason for this may be India’s labour market and labour laws that ensure there are very, very few formal jobs even in the cities. But the lack of formal jobs does not mean necessarily that there are few jobs. What it does mean, though, is that many workers from the country rarely bring their families as they make the big journey, because of the lack of job security. They simply camp out in the cities, with their vast and expanding range of cheap accommodation and slums, but return when they can – or when the work dries out – to their home villages. Such workers, of course, will not necessarily appear on the city’s population figures – and their families at home never will. But it means the ties between city and country are becoming ever stronger – and the number of Indians piling on to the green buses is soaring by the month.

For westerners visiting Indian cities, it can be hard to imagine how they can be such a draw. Why on earth would anyone want to leave behind a quiet village in the country, where the air is clean, and the only sounds are often lowing cows, for the appalling slums, filthy streets, foul air, constant din, spiralling crime and job insecurity that characterises the worst of Delhi and Mumbai? Even the best-intentioned Indians can’t quite understand it. Every now and then, the authorities make a sweep of the textile sweatshops in the city slums where young boys work long hours in dreadful conditions. They close the business, and carefully shepherd the boys back to their home village in the country. But instead of welcoming home their ‘rescued’ boy, the family weep at the tragedy that he has been caught – and it will probably not be long before he’ll be off to the city again. For young men, the pull is powerful.

Village India

For Mahatma Gandhi, India’s half a million or so villages, home to over seven hundred million people today, were its lifeblood. The village was where India’s soul resided. They had an almost spiritual hold on India’s imagination. For Gandhi, India’s cities were foreign implants – a cancer introduced by the British – and if India could only regenerate its villages, it would be healed and find its true way forward. When Independence came, the poet Rabindranath Tagore proclaimed, ‘We have started in India the work of village reconstruction. Its mission is to retard the process of vacant suicide.’

For many journalists and intellectuals, India’s love affair with its villages is over – or should be. But the elite – especially in the cities – keep alight their old flame of a rural idyll with a tenacity that is only made more intense by their distaste for the brash consumerism of India’s growing cities. And the reverence of the village is still very much alive in the paternal side of India, in India’s traditionally minded civil service – and even in the countless nobly intentioned charity organizations who try to bring succour to the rural poor.

THE VILLAGE COMMUNITY

To the casual observer, the Indian village presents the same simple picture it has done for thousands of years. A handful of mud-plastered huts or houses cluster beneath the shade of a few bedraggled trees in the midst of green or dusty fields. Rice, wheat, lentils, vegetables and fruit begin to burst through the dun-coloured soil, carefully nourished with irrigation water. Women in richly coloured flowing robes move gracefully by with pots or woven baskets on their heads, and men in loose baggy clothes amble hither and thither, while cattles low and oxcarts creak. Every now and then, the people of the village assemble around the village tank (the pond) or worship at the temple, which is often dedicated to a Hindu god unique to that village.

But this simple picture disguises a much more layered and less idyllic reality. Most Indian villages are small, with four out of five being home to fewer than a thousand people, but that tiny group of people may be divided into up to forty different castes. Factionalism and divisions dictate the pattern of life. Every one of these castes has its own place and its own tasks – carpenters, blacksmiths, barbers, weavers, potters, water carriers and so on. At the top are the upper castes who own most of the land – such as the Jats in the north-west, Hindu Thakurs and Muslim Pathans in the centre and Brahmans in the south. At the bottom are the landless labourers, the lower castes, and those so deprived they are beyond the caste system altogether. The rites and privileges of the different factions are protected fiercely, and many a low-caste member has found himself or his family beaten or even killed for taking water from the wrong place, trespassing or even less.

Rural prison

For the poor themselves, the village has never been any kind of idyll. They might be calm and tranquil places for the upper caste who own most of the land, and relax in their country villas. But for many other villagers, life in the village is life on the edge. For the lower castes especially life can be tough. They typically own little land and depend almost entirely on their meagre and occasional pay from the landowners. In fact, more than a hundred million of India’s rural poor own not even a scrap of land big enough to sit down on, let alone to grow a few vegetables. People such as these are especially hard hit by the frequent droughts and crop failures. Whereas the higher castes in the village can often ride out the worst, the lower-caste labourers are soon laid off and left to fend for themselves. India’s average income is pretty low anyway, at US$750 a year, but in many villages, the average drops to just US$150 – and some people experience a degree of poverty and deprivation that is beyond even what Africa can inflict.

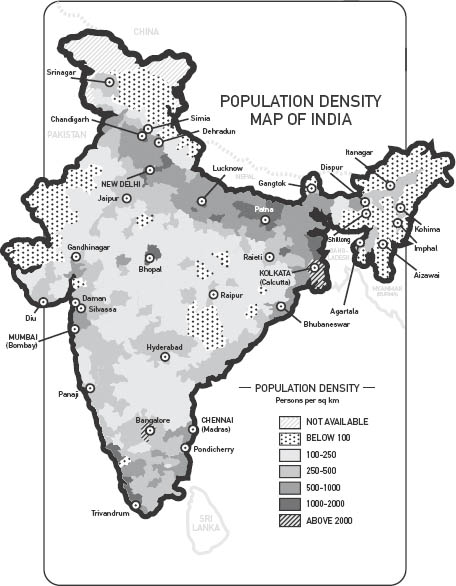

Source: Census of India, 2001

Dalit politician Bimrao Ambedkar recognised long ago how much of trap the villages are for the low castes, imprisoning them in poverty and servitude. They were for him ‘a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness and communalism’. In an article in the US Washington Post, Amy Waldman describes how a village migrant called Shankar Lal Rawat was happy to spend the nights sleeping on a tiny patch of pavement in the city of Udaipur, waiting for contractors to hire him as a porter or construction worker for just US$2 a day. He was from one of the ‘Backward’ groups, an Adivasis, and back home in his village, the caste system ensured that one upper-caste landlord, Jaswant Singh, had complete monopoly over most of the land, moneylending and even access to water. Jaswant Singh paid Mr Rawat just a dollar a day to work in his fields, and then took most of that back through exorbitant charges for water and for the loans they were forced to take out.

No wonder, then, that so many villagers are drawn to the cities, however difficult the transition. In the cities, a young man who lands any job, however arduous, can suddenly find himself earning a comparative fortune. There are now half a million people working in the diamond industry in Surat, where seven out of ten of the world’s diamonds are now polished, and they earn on average about US$2,400 a year – nearly five times the national average wage. A young man from a village may be earning fifteen to twenty times what he would get back home. Often a young man working in a good job in the city will be able to send home as much every month as his father earns in an entire year in the village. Of course, there are plenty of jobs in the city that pay absolutely rock bottom wages. But for many people from the villages, a job is a job – and at least there is money coming in, however little. Even beggars do better in the city.

The money-order village

India is developing a money-order economy, in which countless villagers are sustained by regular payments sent back by sons, fathers and brothers working in the cities. For many village families, these payments are a lifeline, protecting them just a little against the worst that droughts can throw at them. Often they can be much more, providing them with the kind of life improvements, such as proper houses, little luxuries like TVs and so on that they could not even dream of otherwise. Indeed, it seems likely that it is the city workers’ money-orders that are probably doing more to alleviate rural poverty than any number of government initiatives.

Interestingly, the metro migrants bring home to the villages when they return more than simply cash. They are bringing home new attitudes. Many villagers have sunk into a kind of lassitude or fatalism after centuries of hardship and caste discrimination, and often simply can’t find the motivation to make even the minor improvements in their lives that they could. Metro migrants returning from the cities with cash in their pockets and the fruits of hard labour bring a new kind of energy and drive to some back home – and a feeling of alienation to others.

The metro migrants are changed by their experience in other ways, too. They often learn to speak a new language. Hindi, the lingua franca of the cities, is rapidly displacing the regional languages spoken mainly in the villages. And they often gain a new outlook on life. Caste ties begin to become less important as they are thrown into the urban mix, and they begin to develop new mores.

Rural poverty

If there is any doubt as to why so many Indian villagers are sending family members to work in the cities, you have only to look at the figures for rural poverty in India. In 2001, more than a quarter of Indian’s population lived in what is described as ‘absolute poverty’. That was, remarkably, over 40 per cent down on the figure for 1991, so there is no doubt that India’s boom is spreading through the country, and India’s defenders are perhaps right to say that real progress is being made. Nor is the growing prosperity confined to the cities. Incomes are rising in the countryside, too – through mainly industry and services rather than farming. Tens of millions of rural dwellers now have access to pressure cookers and TVs, Scotch whisky and scooters.

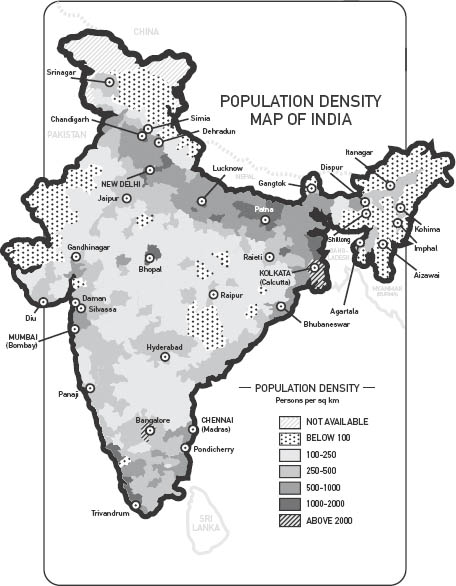

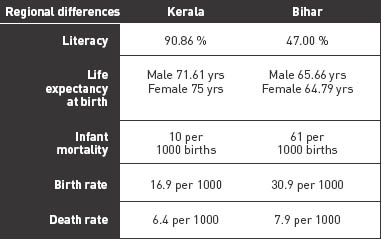

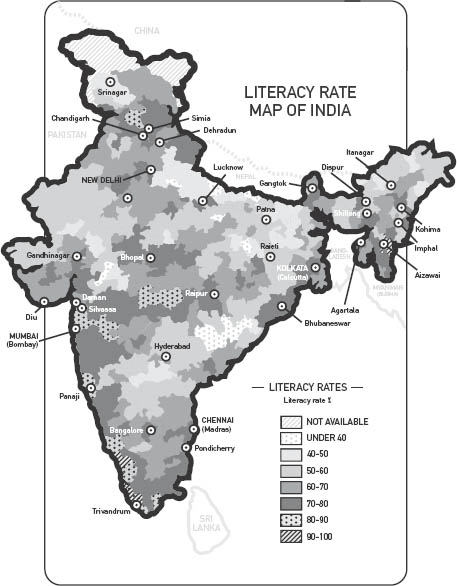

However, there are still many, many – hundreds of millions – in rural India for whom life is desperate. More than three hundred million people live on less than a dollar a day. Nearly half of all Indian children are malnourished. Half of all adult women suffer from anaemia. A massive 40 per cent of the world’s poorest people live in the Indian countryside. Over the last decade, infant mortality has progressed less than in Bangladesh. The adult literacy rate in some rural states is among the lowest in the world. The 2006 UN Human Development report, which ranks countries according to various measures of human health and welfare, put booming India 126th out of 177 countries – behind Equatorial Guinea and Tajikistan and barely ahead of Cambodia – despite the wealth and progress in the cities, because it is dragged down so far by rural deprivation. Most shockingly of all, just a few dozen miles outside Mumbai, where some people are living a highlife that rivals any in the world, there are at least a few children starving to death in almost every village. Such wealth gaps exist all over the world, from London to Sydney, but in India, they are extreme indeed. The upper and middle castes may be beginning to benefit from the trickle down, but all too many are being left higher and drier than ever.

Source: Census of India, 2001

The Singh initiative

To many people, India’s economic boom seems a members-only affair – leaving the bulk of India’s villagers far outside – and the defeat of the BJP-led coalition in the 2004 election was widely seen as a backlash against the exclusivity of the new wealth. Manmohan Singh came to power pledging to make a priority of tackling rural poverty, and the measures he has introduced in the last few years suggest he is serious.

Singh’s flagship scheme is the National Rural Guarantee Scheme, which is probably the most expensive rural support scheme ever launched in India. One of the problems for the landless poor is that, in poor years, they are simply not taken on by the landowners to work in the fields and they are left with no income for much of the year. The idea of the National Rural Guarantee Scheme is that one member from each of India’s sixty million rural households will be guaranteed one hundred days of work a year, and will receive 60 rupees (about £1) for every day they work. The wage is set low to ensure that only the genuinely desperate sign up. People employed will be set to work on projects such as building roads, filling in potholes, digging irrigation canals and working on water-conservation schemes.

Similar schemes have been tried before, but this is on an unprecedented scale. It started in 2006 in India’s two hundred poorest and least developed districts, but by 2009 should extend across the entire country. By then it will be costing many billions of pounds – maybe some 2 per cent of India’s GDP. Critics say the government does not have the funds for such a scheme, and that it will make little real difference – arguing that these patch-up schemes are no real substitute for real investment in rural infrastructure. But Manmohan Singh believes that the alleviation of the suffering of India’s poorest is essential – and putting just a little money – and a little pride – in the hands of these people may stimulate the economy more than grander schemes.

Farming in crisis

What’s interesting is that none of the jobs in Singh’s scheme is farmwork. The problem is that farming is no longer providing a real income for many of India’s country people. Over a third of India’s rural households now depend on non-farm income and the proportion is growing.

Until the 1960s, India was notorious for its dreadful famines, which wracked the country from time to time. As Amartya Sen (see here) has demonstrated, the causes of these famines were as much political as natural, but whatever the reasons they were one of the country’s great tragedies, and dealing with them was one of the government’s top priorities. The breakthrough came in 1968, thanks to Norman Borlaug, the Norwegian–American agronomist who introduced the idea of hybrid grains. Hybrid grains were created by deliberately adding the pollen of one strain of the crop to the seeds of another to combine their qualities. In this way, hybrid varieties of wheat, rice and corn with shorter stalks were created that grow very quickly and produce a heavy grain yield, since less of the plant’s energy goes into the stem.

When hybrid grains were introduced to India in 1968, the effects were immediate and dramatic, creating what has been called the Green Revolution. Annual wheat production soared almost overnight from 10 million tonnes to 17 million tonnes – and went on rising. Annual wheat production in 2006 was a staggering 73 million tonnes. Amazingly, grain production went on rising in line with India’s rising population and it began to seem as if the ghost of mass famine would never stalk India again as the country became completely self-sufficient in its staple foods. But in April 2006, an Australian ship, the Furnace Australia, docked in Chennai.

PROFILE: AMARTYA SEN

‘I thought it was a major defect of the Stalinist left not to recognise that establishing democracy in India had been an enormous step forward. There was a temptation to call this sham or bourgeois democracy. The left didn’t take seriously enough the lack of democracy in Communist countries.’

In England where he lives, few people outside academic circles have heard of Cambridge economist Amartya Sen. But in India where he was born in West Bengal in 1933, he is something of a star. When he won the Nobel Prize in 1998, he was dubbed the Mother Teresa of economics, and in India he was mobbed by crowds ‘wanting’, as historian Eric Hobsbawm has put it, ‘to touch his fountain pen’.

Amartya Sen has made major contributions across a wide range of social, economic and political studies, and has probably been given more honorary degrees (over fifty) than any other academic in the world. But it is his work on the economics of poverty that has makes him such an important figure.

Sen’s argument is that poverty is political. He believes that famines just don’t occur in democracies, because someone will ring the alarm bells before things reach crisis point. Sen makes a comparison between China and India. China is in many ways is better equipped to keep its people fed than India, and yet China suffered a terrible famine in the early 1960s that killed nearly forty million people. India, so prone to famine in the days of the Raj, has had none since it became a democracy in 1947. This is not a coincidence, Sen believes.

Sen is also revered for his work in creating the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI), a powerful system for comparing the social welfare and human condition between countries that is now widely accepted. Before Sen’s work, comparisons of things such as literacy rates seemed woolly and meaningless. Sen created a rigorous framework that has turned the HDI into a crucial tool not only for comparing the development status of different countries but also an essential guide to improving the lot of billions of people around the world.

Sen argues that poverty makes people as unfree as any other political tyranny, in that it stops people having any freedom of choice in their lives. Witnessing Hindu attacks on Muslims when he was young has also turned him against the tendency to champion community values – which is why, incidentally, he doesn’t believe that we should encourage pluralism in multicultural Britain.

Sen has been Master of Trinity College Cambridge since 1998 – the first Asian to become head of any Oxbridge college – and this may be one of the reasons he is so revered in India. For upper-caste Indians at least, he is someone who has made it in Britain.

The Green slowdown

The Furnace Australia looked no different from hundreds of other boats that dock in Chennai every week. What marked this boat out was that it was carrying 0.5 million tonnes of wheat. It was the first time for decades that India had needed to import wheat and a further 3.5 million tonnes was imported later in the year. Government spokesmen simply put the problem down to droughts and floods, which had reduced India’s normally abundant harvest. But other people began to ask questions.

First of all, people began to ask if the Green Revolution had finally run out of steam. India’s farmers have performed miracles in boosting harvests year by year as India’s population grew. But have their crops reached their limits? Many agronomists doubt if any higher yield can be squeezed out of the already hard-working grains.

Second, farmers are finding that it is harder and harder to make a decent income from growing staple crops. The real money in farming comes from growing ‘cash crops’ for export, such as coffee and cotton, mushrooms and sweet corn. An acre of mushrooms, for instance, may yield as much as 10 acres of wheat. Moreover, several mushroom and corn crops can be produced in a year, compared with one for wheat and rice.

Third, the Green Revolution has placed enormous stress on land resources that is beginning to affect yields. To keep these boom harvests going, farmers have begun to draw on deeper and deeper water resources – and the underground water in many places is now running out. To make matters worse, the quality of the water has deteriorated through the build-up of the intensive pesticide and fertiliser applications that have been needed to sustain high levels of productions. Hybrids, with their short stems, for instance, are far more vulnerable to pest infestation than traditional crops and so need copious pesticide treatment. This has a human cost, too. According to Amrita Chaudhry, agriculture correspondent of the Indian Express, there are entire villages in the south-west of the country where every family has at least one or two cancer cases, a possible side effect of excessive pesticide exposure.

Farmer suicides

For some commentators, though, the most distressing aspect of the aftermath of the Green Revolution has been the way it has undermined the Indian farmer’s self-sufficiency. Before the Green Revolution, each farmer would save some of the seeds from each year’s crop to plant next year’s. Hybrid seeds are infertile, so, each year, the farmer has to buy new seeds. And he must not only buy seeds, but also fertilisers and pesticides to make sure he gets the proper yield. The problem is that margins are tight, so in order to buy the seeds and the chemicals, farmers have had to borrow money – typically at the exorbitant rates of the village moneylenders. If the crop fails for any reason, as is often the case in India, with its unpredictable droughts and floods, then the farmer not only faces a food crisis, but also a cash crisis, because he has no income to repay his loan and no income to pay for next year’s seeds.

The result is that countless Indian farmers have been trapped into a spiralling web of debt from which they can see no escape. With no way of escaping, many of them are simply taking their own lives and India is now suffering a wave of farmer suicides. In 2003, the last year for which figures were available, 17,107 farmers were known to have committed suicide, and the basic statistics probably barely scratch the surface of those who simply died from hunger, illness and deprivation – or have simply had their lives blighted. The high rate of farmer suicides is a hot political potato, and the pressure on the government to do something about it has been growing.

Opposition has been steadily growing in India to the impact of American multinationals, which bring both new opportunities to India’s farmers and also land them deep in debt. Following on the heels of the grain traders such as Cargill are biotech companies such as Monsanto, which sell pesticide resistant, genetically modified (GM) seeds, and also the special pesticides needed to make them grow well, luring farmers into deeper debt. In 2005, sales of Monsanto’s Bt cotton (a type of cotton genetically modified so that it can produce its own pesticide) doubled in India, but in a landmark action in 2006 the government of Andhra Pradash forced Monsanto to slash the cost of its seeds. Monsanto is challenging the ruling in India’s supreme courts at the time of writing.

KARGIL WARS

US multinational Cargill is the world’s biggest grain trader, handling a staggering proportion of the world’s grain trade – and in 1999 it decided to move in on India. By a strange coincidence Cargill’s name is spelled in just the same way in Hindi as Kargil in Kashmir, where the Indian army was clashing that year in a bloody skirmish with a Pakistani force who had crossed the LOC. Cargill launched its ‘Nature Fresh’ flour in India in exactly the same week that the Indian army successfully stormed the Kargil heights. Both farmers and government officials were convinced it was some new deeply patriotic brand. [Not slow to miss a marketing trick, Monsanto (see below) named its hybrid maize seeds ‘Kargil’.]

Prosperity and poverty, satisfaction and discontent are all on the rise in India’s countryside – some people seeing a bright future, others a very dark one. None are quite as discontent as the Naxalites (a radical, sometimes violent revolutionary communist group), but whatever the days to come, few doubt that India’s age-old rural way of life, which has persisted since the days of the Harappans, is changing and changing dramatically.