Reel 9

Sturm und Drang

Sc. 1 Introduction

The excerpts reprinted in Reel Nine encapsulate something of the publication’s effort to establish credibility with readers, who would have known perfectly well that MSNL were professionals in motion picture sound, but amateurs in publishing. One agenda shared by the contributing team was to uphold MSNL as a noncommercial alternative to the marketing ballyhoo we observed in slick magazines. Whether promoting big studio blockbusters, the Hollywood star system (and our own generation’s misguided faith in Star Directors) or the cornucopia of new home entertainment hardware, the team counted it all shameless hype. With our Counterculture ideals, we thought readers didn’t need to participate as passive consumers and would want honest dialogue.

Ironically, the informal and breezy writing style we tried to emulate may have come unconsciously from some of the same popular movie magazines whose blatant commercialism we disdained. At times the style may have awkwardly impersonated the insider shorthand of Daily Variety. How could anyone schooled in English resist the provocatively encoded headlines (“HICKS NIX STICKS PIX”)? But Variety has been selling paper to the entertainment industry for 110 years. MSNL were just some kids who wanted to talk about soundtracks.

Sc. 2 Editorial Notices

Publishing When is a Newsletter Really a Journal? provided some relief from the self-imposed pressure to print on a schedule and attempted to divert us from the masthead’s implied claim to be timely in updating readers on the latest inventions and trends in movie sound.

When is a Newsletter Really a Journal? Published Fall, 1994 (Vol IV #1)

When is a Newsletter Really a Journal?

Sometime in the Summer of 1994, in an off-guard moment between film jobs, the editor and publisher realized that MSNL had quietly slipped past its fifth anniversary. We began twenty-eight issues ago, by attempting to alert readers in a timely way about exciting events unfolding in the new technology of motion picture sound, balanced with thoughtful pieces regarding quality and ethics in every element of the craft. We wanted to encourage readers to seek out and demand the best possible experience of projection in theaters, and we sought to stimulate dialogue about the misunderstood arts of making sound for movies.

With dialogue, we thought, would evolve some seminal ideas that may eventually gel into a shared aesthetic. Whenever we visit film classes to discuss our work, we are surprised at the misconceptions over the actual process of post-production work, yet we find that people have great theoretical ideas about sound. In the real world of sound work, one would be surprised to find a conscious thought about aesthetics on a theoretical level. Those high points we celebrate in sound crafts were reached by the accidental synchronicity of talented people working under the right conditions, on the right film. Sound people are not primitive artists, whose work will be assessed by a later generation of critics. Many of them are college graduates, even graduate scholars, working in an environment that often sports the trappings of blue collar industry, modified by fast-lane politics and the pressure that comes with high-stakes financial gambling. It is not a world that compares to anything familiar on planet Earth. It is Hollywood.

Carving Our Niche

A newspaper is a daily journal, from the French word for daily. A personal journal is a daily record of private thoughts. A journal of the arts is a collection of thoughtful essays and dialogue meant to enlighten the reader… however pleasing or angering the participants, it must certainly stimulate. It is the latter type of journal that MSNL wishes to emulate.

We will never compete with slick magazines, carrying heavy advertising from the audio hardware industry. We cannot publish quickly enough to give timely news of new technology before anyone else. For instant gratification junkies, there is a universe of factoids available on the Internet.

Although we place a high value on the immediacy of news when world events unfold before our eyes on CNN, we prefer to learn about the meaning of events by watching experts analyze them in a more remote context. The sound bite is not the event itself. What we have here exclusively is an inside track on the making of sound tracks.

So we would like you to consider us a journal, no matter what the registered name on the masthead implies.

“Responsible journalism is journalism responsible in the last analysis to the editor’s own conviction of what, whether interesting or only important, is in the public interest”

—Walter Lippman

Sc. 3 Opinion: Going to the Movies

Reel Nine continues with five (easy?) pieces, about experiencing sound from the point of view of professional moviegoers. Fascinating Foley, Picture Palace Etiquette, Made of Mud, Never Again Dep’t., and Pacific Venues deal respectively with the public’s being exposed to the still arcane and little-heralded art of Foley, the antisocial behavior of some audience members, and some inexcusably bad theater exhibition situations.

Presaging her later written work in The Foley Grail, Vanessa Ament shared her excitement that the craft was beginning to gain some recognition in the form of public presentations by her colleagues: in Los Angeles theaters, a New York Times article, and a segment on NBC-TV. She pointed out that, while those public relations exhibitions, fully in “show biz mode,” were less than objectively documentarian, they could be seen as useful promotion of the sound crafts. In Fascinating Foley, Ament applauds the Times for contextualizing sound in films, and the NBC piece for showing an unglamorous example of behind-the-scenes professionalism. Prof. Ament consistently emphasizes how Foley artists each do the things they do quite differently, (and twenty-three years later, The Foley Grail describes major differences both by regions in the U.S. and by Foley artists internationally) and she cheers on any efforts by news media to raise the general awareness of film sound for a curious audience.

Editorial: Fascinating Foley Published Winter, 1994 (Vol III #3)

Editorial: Fascinating Foley

It has been several years since the mainstream media has made Foley a focus for the general public. This summer has, to date, yielded three stories aimed at drawing attention to one of the less promoted aspects of movie sound. All three demonstrate the art of Foley as illustrated by several of our more prominent artists. The Los Angeles Times has a series of filmed promo spots shown in Southern California movie theaters prior to “Coming Attractions”, (pre-previews). The most recent one features John Roesch and Hilda Hodges demonstrating Foley techniques they use for enhancing and replacing sounds that are typically found in the Foley repertoire. This minute glimpse into the Foley world is, for viewing purposes, a more theatrically presented version of a day in the life. Still, professionals in the post-production world are always appreciative of any educative attempt to illuminate an important but lesser-known craft that has become an essential element of any self-respecting sound track.

The New York Times published an article by Brendan Bernhard (July 10, 1994), which describes the craft as performed by New York Foley Artists Brian Vancho, Elisha Birnbaum and Rick Wessler. Mr. Bernhard’s article presents a rather elementary perspective on the peculiar job of adding synchronized sound effects to a piece of film. It communicates very nicely to a lay audience that has previously been totally unaware of the Foley Artist’s contribution. Another valuable addition in this article is a perfunctory list of items any artist would need on a Foley stage.

On Dateline NBC (July 26, 1994), two Hollywood artists, Ken Duvfa and Dave Fein are shown in the nitty-gritty of daily “Foleydom”. We see them as they normally dress, doing what they do and have done every day for many years. The audience gets a sense of the environment, the required teamwork, and the reality of the task at hand. As veterans in the sound biz, we at MSNL found Dateline’s peek into the world of Foley to be fresh and relevant.

What is most fascinating is how the three stories utilize different approaches. The glitzy, bigger-than-life representation of the Foley Artist in the L.A. Times promo shows the attractive artists, nicely dressed and very cheerful. One gets the impression that they love their job and it is truly “magic time”. Mr. Roesch is shown throwing his body down on the ground repeatedly for the correct sound of a body fall. Ms. Hodges demonstrates body hits using a pad, some celery and a wet chamois. Of course, this piece is pure “show biz” and is meant to grab the attention of a movie watcher and get additional devotees to the newspaper. In reality, most Foley Artists dress comfortably in indestructible yet audibly imperceptible clothing which allows freedom of movement and no heartbreak if dirty water, mud or corn starch is covering the clothes at the end of the day. Also, although it is true that Mr. Roesch does, at times, do “Method Foley” when creating body fall sounds and other effects, it is a misrepresentation to imply that all of the legitimate artists adopt the same practices. The means to the end can be very different with any artist depending on the film, time allowed, sound effects library to be used by the sound editors, and of course, the particular perspective and talents of the artist. As with any art/craft, Foley is subjective and all artists bring a piece of themselves to it.

The strength of the New York Times piece’s simplicity is its distillation of the craft down to the generic basics. Any average person can understand from Mr. Bernhard’s article what the key parts to Foley in filmmaking addresses. One can relate to adding sounds to a movie after it has been filmed because of extraneous noise on the set or the need to enhance the sounds for dramatic purposes. Also, the particular peccadillos of directors are referred to, as well as the troublesome trend of sound tracks becoming bigger and less realistic almost daily.

As for Dateline’s attempt at realistic journalism (with a touch of hype to make it interesting to Middle America), it mostly succeeds. Mr. Duvfa and Mr. Fein are presented as they usually appear to be when creating Foley sound effects. Here are two professionals, working on another film together, as a team. There is no grandiosity or flash. They have a job to do which they are very used to. It has its rewards, its stresses, and its redundancies. They make it look easy, not because it is, but because a professional knows how to simplify the process so s/he can do it every day for years.

Several years ago there was a cycle of media pieces on Foley. It is a positive sign that the interest in it has increased rather than waned. These artists depicted in the media work very hard to add a positive contribution to the world of sound effects in movies. They drive through traffic, work very physically for long hours, are relied upon to be spontaneous and yet open to the sometimes over-ambitious directions of an editor or director, handle lots of odd and sometimes awkward or heavy props to “layer” sound on top of sound, get dirty and exhausted from the usually filthy Foley stage, and finally, after all that, clean up the stage with sweeping, putting away props, dumping broken glass, and reorganizing their shoes. They will be back tomorrow to do more of the same, with a cup of coffee, more “Foley-proof” clothes, and a smile. After all, they are lucky enough to have a job they like, which has its share of creativity, and a decent scale of pay. And sometimes, just sometimes, they are featured in a story which is highlighting the work to which they are committed.

—VTA

Editorial: Picture Palace Etiquette Published January, 1990 (Vol I #9)

Editorial: Picture Palace Etiquette

Every so often, we at MSNL have a theater experience which brings to mind an idea. Recently, while attending the re-release of Raging Bull, your editor and publisher noticed a behavior that is becoming all too frequent. After most of the people located seats and got settled in, a few other film goers entered late, sat directly in front of a couple (with many other seats available) blocking their view of the screen and causing a chain-effect, with a plethora of those previously seated anxiously moving around trying to renegotiate a viable seating arrangement. The musical chairs was particularly noticeable because the theater was small. This made one person’s change of seat an event for the entire group of people. Several people left for refreshments midstream then reentered the arena with a new seating arrangement, causing the domino effect to begin again. Thus, the first forty minutes was most distracting. Years ago, there would be a request on the movie screen for women to remove their hats. While hats are not fashionable enough to require that particular reminder, the spirit of it is still apropos. Perhaps we can all keep in mind the viewing pleasure of others when locating the optimum viewing spot for ourselves… just a thought.

—VTA

Editorial: Made of Mud

While exploring New Mexico recently, we discovered that, among the charms of the high-desert culture in Santa Fe one does not find big-sound movies. One theater was running Tremors in 35mm Dolby stereo, and we were told that it’s the only stereo venue in town, and they only installed stereo when Back To The Future II opened. In another theater, we asked one bright young man while he shoveled popcorn for the customers, where one goes to hear a good stereo soundtrack. “Stereo?” he replied, “Mister, this is Santa Fe. Everything’s made out of mud! We never heard of stereo!”

There are 16 screens in 8 locations in Santa Fe, including one en español. Santa Fe has nearly 200 restaurants and innumerable galleries. The clothing stores show some of the finest wearable art in the country. And the New Mexico Repertory actors perform in a handsome new high-tech theater, on a stage that is the pride of the state. What a shame there’s no equivalent theater for showing movies!

Santa Fe is the sort of town whose biggest box office is at the “art house” cinema, while run-down shopping center triplexes with maladjusted monaural sound struggle to survive the video era. They do enjoy their Bergman and Woody Allen pictures there, but with the cultural bias against entertainment movies, who gets to experience big-screen audio? Typically, people in areas with a high level of education work so hard to develop the classical arts, they throw the baby out with the bath water and tend to ignore popular or mainstream arts. Their perspective is narrowed down to only those events that fit their cultural paradigm. So the pleasure of big soundtracks is denied them. Intellectuals may be compelled to make judgments about popular culture, but does this mean that a market like Santa Fe will never have a place that specializes in 70mm extravaganzas?

The sense of a dichotomy between slick technique and film-as-art is a dangerous idea. Is Lawrence of Arabia less beautifully executed because it plays better in 70mm with six-track sound?

Culture fans began to appreciate motion pictures only by the time Silents had begun to look archaic. If talkies were mass entertainment, then everything silent could be given classical status, or so went the silly reasoning of some filmgoers. In the early days of color and wide screen, we lusted after anything shot in black and white. What kind of aesthetic is that? Do we mistake popular junk for art, just because it is technically dated?

Hollywood’s hype and ballyhoo make it an easy target for intellectual mockery. But high professional technique is no reason to dismiss a film as “lowbrow.” For example, to hear someone describe the simple premise of Die Hard or Lethal Weapon, you would think they were a couple of asinine shoot-’em-ups. To experience their originality and humor, especially in a big-screen environment, is something else again. Missing pictures like these is to miss the brash, uniquely American character of Hollywood. Wide screen, Technicolor, and high fidelity sound became standards of the industry because they involved us so deeply in the sights and sounds of fantasy. In all aspects of visual and aural excitement, big-budget movies excel. So even when mainstream movies are shallow they provide magic.… And big-scale soundtracks are very much a part of what we appreciate.

MSNL would really like to hear from South-Westerners who could show us that there are sound-oriented theaters we missed in Santa Fe. We technical filmmakers feel very forgotten in a town like that.

—DS

Editorial: Never Again Dep’t. Published July, 1990 (Vol I #13)

Editorial: Never again Dep’t

Our don’t-touch-it-with-a-ten-foot-pole award goes to the Pacific Theaters. Their theater in downtown Hollywood is an old picture palace cut into impossible pie shapes. Audiences don’t even face the screen squarely, as the seats still face what was the center of the old screen. Only corrupt, greedy-guts profiteering would create such an abortion out of the movie going experience. The new walls are too thin to keep out bass notes from the next room. In management’s defense, their Hollywood Boulevard location is something of a combat zone. Politely asking another audience member to stop talking or smoking might get you killed. The youngsters working in the theater seem to face the combat bravely. But there is such a slumlord mentality evident in the condition of the theater, it seems they have given up on standards, and don’t have one imaginative solution to their problems.

Editorial: Pacific Venues Published August, 1990 (Vol I #14)

Editorial: Pacific Venues

The ink was still wet on MSNL Vol I #13’s editorial (We took Pacific Theaters’ Hollywood theater to task for having been subdivided as many old Palaces have been, and for its run-down condition.) when we discovered something another Pacific house has done that we firmly applaud: The management at Pacific’s Sherman Oaks location has hired at least two retirement-aged women to sell tickets and concessions, jobs that usually go to the Clearasil set. Plenty of Seniors need a break like this, and have a solid work ethic and lots of life-experience to bring to the theater lobby. A minuscule step toward a more just society. Nice move, Pacific Sherman Oaks!

Sc. 4 Opinion: Colorizing, Restoration Standards

On the Colorization of Sound …

A shark swims more or less constantly to stay alive, as its gills pull oxygen from the water. Technology makes its headway through time, sometimes as mindlessly as a shark, and can be adopted by the film industry simply because its novelty is appealing. George Carlin notably reversed Plato’s aphorism when he observed, “Invention is the Mother of Necessity.”

New technology is an important part of how popular culture works to create new entertainment, but it also offers new choices for restoring and exhibiting older movies. Active cineastes understand that each experience we have with a movie is inextricably tied to the context of its particular edit, release format, and exhibition circumstances. We know we can see The Third Man (1949) for instance, every few years as reproduced on a new medium, with or without a theater audience, etc., and count each restoration and each viewing/audition as unique. For us, that is analogous to the theatergoer’s enjoying the same play on different nights.

Scale

With advances in A/V reproduction, classic movies re-enter the popular culture in different versions, sometimes restored for the best large-scale presentation to a full audience, and lately as iconic samples and clips in miniature, suitable for personal viewing. We should not be surprised soon to see internet vines being built from six-second loops of Jimmy Cagney shoving that grapefruit into Mae Clark’s face from The Public Enemy (1931), or to watch and hear Orson Welles pronouncing “Rosebud” ad infinitum as someone’s smart phone ring.1 Someday, those little entertainment loops will themselves become iconic and become imbedded in another layer of pop culture, just as happens to music samples, and younger people will have no idea where they might have originated.

Speed

Because movies have to aggregate more skills, technologies, and other arts than anything else, the medium itself will frequently become part of the message (to mangle Prof. McLuhan’s more complex idea momentarily). Early in the sound era, short subject comedies were outfitted with ridiculous sound effects (recordings of percussionist’s drum kits and whistles) to make them appealing to general audiences unwilling to sit still for silent film. Between that practice and the unforgivable failure of distributing companies to print at the correct speed,2 average audiences would have completely missed some of the nuance and subtlety of the great comedians’ work, the best of which had everything to do with timing.

Light

Much as the imposition of new technology on older films created offensive distortions of time, colorizing could do the same with light. The business of continued distribution of old movie titles, particularly for the evolving home theater of the 1980s and ‘90s, created that marketplace. What colorizing, screen ratio alterations,3 and synthetic stereo did to compromise the art of classic movies was often the subject of Moviesound Newsletter editorials and letters.

The colorization of classic black and white films struck our colleague film professionals as a revisionist outrage to the history of the art. When a colorized version of The Maltese Falcon (no, students, not the Millennium Falcon, but The Maltese Falcon, 1941) showed up on a friend’s television in the middle 1980s, the author attempted to adjust the TV’s color setting down to stark black and white. No true black and white adjustment being possible, we had to settle for a compromise: a kind of lightly color-tinted image, reminiscent of the water-color-tinted prints of studio production stills, often seen on theater lobby cards. Such an image revealed flaws and dirty patches in the costumes and set pieces in every scene, which would never have been exposed by black and white prints. Admittedly, Warner Bros. films noir were cheaply produced (that is part of their charm) but when Brigid O’Shaughnessy’s elegant apartment looks as dirty as Sam Spade’s shady office, something is off. The original photography is designed to ignore certain flaws inherent in recording light monochromatically, and the audience can suspend disbelief. The new technology has revealed production flaws that compromise the art.

The business of colorizing (exploiting the new marketplace for films on VHS tape) had the unintended consequence of stimulating restoration efforts of long-neglected black and white film negatives. MSNL thought to put the whole thing in context. Film restoration had been until then the exclusive purview of notfor-profit academic institutions: The Library of Congress, The American Film Institute, well-funded art museums, etc. It had taken the enormous research efforts of historians and expensive technical craftsmanship to save films (from nitrate deterioration, butchering by local projectionists,4 and the dumping of studio inventory to clear storage space) from obliteration. Today, we know that thousands of titles are gone forever, as bizarre as that may seem to students living in a bountiful forest of accessible media. At the end of the analog age, restoration had become something of a favorite charity to many of the “Film School Generation” directors: Coppola, Lucas, Scorsese, Spielberg, and others contributed time and funding to the academic efforts of film restoration scholars. MSNL writers had a growing awareness of the urgency of film restoration and how it compares to the painstaking work of art conservators and restorers who maintain the world’s great paintings, prints, and sculpture.

Experts curating classic works of visual art hold closely to their protocol that no modern application of repair pigment or plastering should visibly alter the original image, nor should the modern materials be in physical contact with the ancient layers. Instead, the new touch-ups are only in contact with a neutral and invisible protective layer. To put the urgency of this ethic in contemporary Star Trek terms, that protocol is well understood to be their “Prime Directive,” and something like it applies to film restoration, only with added complication:

Films are not completed artworks to be left in an entirely fixed state in perpetuity. Every edit creates a different presentation. Every screening adds unique qualities to the experience. In post-production sound work, late editorial changes have become customary. An old aphorism that said “A picture is locked when you can rent it at the video store,” assumed that was the point when a studio would stop tinkering and move on. But since the 1980s, beginning with Laser-discs and proliferating through the DVD era, later releases of Director’s Cuts and other alternate versions gives the lie to that little proverb.

Editorial: The Colorization of Sound Published April, 1989 (Vol I #3)

Sc. 5 Editorial: The Colorization of Sound

What would we do without Ted Turner? We would have less to talk about in the biz, that is for certain. Few of us have missed a viewing of Gone With the Wind either on television with the barely tolerable commercial breaks, on video, or if the universe is with us, in a real theater with good sound and polite neighbors. Recently, this reviewer was fortunate to revisit this old and beloved friend at the Nuart theater in Los Angeles with several hundred Scarlett and Rhett groupies. Some queries came to mind. Would the restoration of the color be vivid? Would the improved sound add to the spectacle? Well, Ashley, the truth is this is a mixed review. In some scenes the color was fabulous, in others, drab and inconsistent. Some of the scenes had mysterious ghosting of the characters and scenery. Casper and his buddies are not mentioned in the credits, so who can say whether this was a result of age or poor restoration? Sound-wise, Turner and his sound mavens took a mono dub from the ‘Thirties and tried to make it a stereo track from the ‘Eighties. Bad idea. Dialogue would jump from center screen to left or right and was both jarring and muddy. The added Foley was artistic but a bit overdone. Ted, old buddy, let’s do lunch and discuss the importance of maintaining integrity of an art form. A mono sound track that can be cleaned and restored with today’s technology would have been rich and thrilling. As it is, this sound track is unnatural and distracting. Mono sound and black and white photography are valuable art forms in themselves. So, let’s keep our egos out of other’s creative crafts.

—VTA

Colorizing Pays… For Restoration Published December, 1989 (Vol I #8)

Colorizing Pays… for Restoration

We just saw a brand-new 70mm print of West Side Story. You’ll be able to get the laser disc soon, and we heartily recommend it. But MSNL experienced something that only the Movie Theater can deliver. LA’s Century City Cineplex Odeon treated the picture like a treasure. This is the same venue that ran the restored Lawrence of Arabia (see MSNL #1 and 2) for an appreciative special-run audience early this year.

With the intelligent music of Leonard Bernstein, lyrics of Stephen Sondheim, and the modern choreography of Jerome Robbins, something exceptional was created for the stage and completely reinterpreted5 for the needs of the motion picture. It goes places no stage play could go, yet is faithful to the visual artifice of a stage play, and has a look that only 70mm can properly capture. If you have never seen a print of a 70mm shot on 65mm negative, you haven’t lived in a movie theater. When color, resolution, film grain are nearly perfect, the best sound editing, recording, transferring, and mixing have even more impact.

Among the ten Oscars® this 1961 production won was the one recognizing the Todd-AO and Samuel Goldwyn Sound Department sound. Murray Spivack, who gave sonic life to King Kong, supervised. This sound has been carefully retransferred to accommodate modern theaters.

Although some cost is recovered when a new version is released on video, projecting classic films is not profitable. Each print costs a fortune, and few prints are distributed. These efforts, like any cultural event (support of orchestras, art museums, public radio) depend upon an active public. Some super-star directors raised the money to restore Lawrence, and we were told that recent restorations of Gone With the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, (both 35mm productions from the MGM library) and now West Side Story were funded by Ted Turner.

When the popular audience watches Ted’s TV networks and rents colorized tapes, some of that money filters back to rescue classic film negatives (Black-and-white negatives have to be restored before films are colorized on video anyway). The permanent loss of film materials is a cultural crisis about which the American Film Institute has been warning us for years. Now we’re moving on to restoring the great 70mm films. Is this Turner’s debt to society, paying off the bad karma from all his colorizing? 70mm theaters with 6-track sound and THX playback specs come close to the “feelies” of Brave New World. But we don’t mean anything insidious is at hand. Complete sensory involvement is good at the movies. That’s why we go. Let us know if a 70 classic is shown in your area.

—DS

Restorations and Re-Releases Published October, 1990 (Vol I #15)

Sc. 6 Restorations and Re-Releases

We may be embarking on a Great Restoration Era for motion pictures. For a generation, scholars raised funds from the wealthy and educated to transfer movies from volatile nitrate negatives and reprint them on modern stock. The search for original negatives and missing scenes made many film historians into detectives and academic heroes. Our heritage of film was deteriorating faster than it could be saved. With financial resources being scarce, many common films would go to dust. Desperate scholars bailed out the ship, shouting “Classics and Rarities First!” With the same kind of support that keeps symphonies and art museums alive, elitism necessarily took over.

Many silent classics were saved first, sound being largely ignored until home video became a well-established business. Perhaps we are entering a Phase II now, when films benefiting from restoration money may not be the greatest examples of art, but hold their own as popular icons. Some popular films would never be restored until scholars first felt secure about classics of higher artistic worth, at least as was that worth was perceived.

The resurrected Lawrence of Arabia (MSNL #1 and 2) reminds us of the incredible power of 70mm as an enormous artist’s canvas. It can portray historical drama like nothing else. Ben Hur reminds cine-elitists that slick production technique has nothing to do with art.

Sc. 7 Opinion: Labor Relations, Personal Standards

On Waves of Change and Generations Working …

Entertainment involves large numbers of specialized artists and artisans, the particular value of whose skills rise and fall in history. Exemplified by changes in the photographic and laboratory skills that moved from black and white to color, hand-drawn animation to computer, silent to sound, and monaural to multichannel, the film industry is shaped by waves of change in highly skilled labor.

Sometimes entire generations encapsulate the beginning and end of entirely new professions. The author’s classroom talks will often analogize changes in sound crafts to the example of the animation industry’s cell inkers and painters: There was a population of women already in place, painting cells for the major studios’ animated short subjects. But Walt Disney’s risky production of an animated feature-length film in 19376 required a vast expansion of that labor pool. Scores more of young women in Los Angeles were hired and trained for this work. In the height of the Depression, the young women would be better able to support themselves, and many were young enough to be living with their parents, at a time when everyone was desperate for income. Many of those women carried their specialty craft into the 1970s, when they were elderly or reaching retirement age. Just at the end of their working lives, the difficult art of cell-inking was replaced by Xerographic reproduction on cells of the animators’ pencil drawings; and just a few years later, the process of painting color on the backs of acetate cells was replaced by computer painting “fill” commands.

Sound has benefitted greatly from specialization through the second half of the twentieth century, improving its impact on audiences as it evolved new ways for the specialties to interact. Participation of trade unions and professional guilds (which clarify the best practices of work flow and job jurisdiction as new techniques are introduced) is necessary to the intelligent partitioning of what otherwise might have overwhelmed Hollywood sound in chaos. Such simultaneous artistic and technological evolution has allowed craftspeople to enhance each other’s work and to better serve the individual film, amplifying any director’s narrative voice. Any subjective expression of personal artistry by a sound worker would be subsumed in the general impact of the soundtrack on audiences. Sound served the twentieth century movie best by the Fordist Hollywood process.

In the adolescence of the twenty-first century, new technology allows for more direct impact by sound supervisors who have the skills to edit, sound design, and mix. The best among these people are those who have already experienced making movie sound according to the older, more social model, and consequently have not only a variety of techniques on their palettes, but a clear sense of the broader needs of the narrative. They work as a primary artist-for-hire, as directly collaborative with a film director as was the traditional composer of music, and there usually will be additional sound editing crew whom they supervise. Among the growing number with more traditional experience, currently working in the smaller modern model, are Mark Mangini, Ren Klyce, Paul Otteson, Gary Rydstrom, and Skip Lievsay.

Busman’s Holiday is a little celebration by the author of the pro bono sound craftsmanship performed by Hollywood post-production people for the benefit of student and independent filmmakers. Few moviegoers could have known that professionals were in the habit, and still are, of “giving back” in this way.

From the Editor’s Bench: Busman’s Holiday Published February–March, 1991 (Vol I #17)

Sc. 8 Busman’s Holiday

Many post-production sound people are returning to work on feature films this February after one of the longest employment slumps of recent years. This Fall and Winter we saw quite a few colleagues actively engaged in sound pro bono work. It is impressive that professionals give away their work between paying jobs, helping student filmmakers or friends making directorial debuts on tiny budgets. Why do professionals labor on such projects with the same diligence they invest in Big Bucks movies? The cynical view is that today’s student director is tomorrow’s George Lucas, and the sound pro “giving it away” is gambling on the filmmaker’s future favor. While that’s smart politics, hacking away at strips of film, footsteps, or audio mixing boards in cluttered little rooms for days, nights and weekends is never a small commitment of time. Even if labor is donated for a very short spell compared to the usual working schedule, it requires concentrated effort.

When crafts people choose to work, there may be another agenda lurking underneath: Making movies is addicting in a positive way. Hollywood folks, if you ask about their work, express a love/hate involvement that one rarely hears about in other walks of life. The negative side of the addiction involves being seduced by the impossibly long hours, isolation, and other stresses. There are financial highs and lows that make insecurity the only thing they can depend upon. But most people in entertainment are happy to be working in the arts at all. “Freebies” provide a way of paying back the system that’s been good to them.

And in a world where the concept of community is being redefined; where towns, families, and businesses no longer provide the kind of social bonding they once did, Hollywood is a family of interdependent specialists. There is a mutual recognition of the love of filmmaking: That is the family identity.

For most of us, the act of synthesizing a coherent reality out of tiny pieces of recorded sight and sound has an astonishingly heady effect. Whatever the psychological bait may be, most filmmakers would rather do what they do for no money than not do it at all. Watching movies has always been the great popular escape from a harsh world. Few people realize that making movies, as grim and unglamorous a process as it is, can be just such an escape.

—DS

Sc. 9 On the Abuse …

MSNL’s July, 1989, piece on the short-lived union/non-union split between sound crews racing to support James Cameron’s spectacular underwater adventure, The Abyss, was a statement of concern critical to our professional subscribers. Here was an example of serious employment issues affecting the lives of our peers, which may never have come otherwise into the casual sound fan’s sphere of awareness. As major film projects required sudden expansion of their crews, and the reorganization of their specialties, it became a growing problem that producers had not learned to anticipate. Consequently, blockbusters often tested every boundary of the traditional workflows and of the personal lives of participating workers. Workaday gossip throughout post sound had created another title (it was the custom for editors to pin an epithet on their current jobs with a dose of gallows humor) for Cameron’s project: The Abuse. One of the jobs of the publication was to inform the outsider fans about internal controversies and simultaneously to provoke discussion within the narrow business community of post itself.

Editorial: Aby… Abbeh… Abbbah… Abbuh… Published July, 1989 (Vol I #5)

Sc. 10 Editorial: Aby… Abbeh… Abbbah… Abbuh…

That’s All, Folks!

Have you read all the negative ink that James Cameron’s big bubbler is getting? When The Abyss comes out, we’ll learn whether it’s been worth all the precarious production techniques. The movie mags are clucking that Ed Harris and another actor got the living shit scared out of them during a stunt without aqualungs just because Cameron didn’t trust them to act panic-stricken. There were complaints from all over the production about the director pushing people, exhausting them and setting a steel-hard, heroic example himself. That the innovative production will be visually and dramatically stirring, we have no doubt. We’re even looking forward to the underwater dialogue recorded in sync from mask radios.

But Cameron and producer Gale Hurd were very cheap about their post-production sound work, and they should be challenged about this. The ratio of dollars spent on sound to dollars spent on large-scale visuals is miniscule and shrinking fast. This is an illness all through Hollywood. Stars, writers, producers, and movie lawyers eat up so much money early in the game that, when it’s time to make sound effects, a lot of movies have moths in their pocketbooks. Cameron and Hurd evidently mistrust the Hollywood unions, and take their work out of town whenever possible. The Abyss is as we write, being mixed at Fox, by Don Bassman’s first-class crew (Project X, Predator, Die Hard), which will make the most of their material. But the financial pressure this time fell upon the sound editors, who have to prepare the tracks for Don and his mix masters.

The supervisors Dody Dorn and Blake Leyh had barely enough money from Hurd to hire a handful of inexperienced, non-union editors. Eager to please and make their mark on a “Big Movie”, they bravely faced an overwhelming pile of complex dialogue and big sound FX. As is common with this type of film, (which has become an editorial specialty for established sound shops,) incessant picture changes required the rookies to stay up many nights and weekends adjusting their tracks. A union crew would have been compensated for that time.

Eventually, five experienced ADR editors were added to the crew, creating a mixed (union/non-union) shop. Stay for the credits and see if they’re acknowledged. The Editors’ Guild stepped in and signed everyone into the union. The happy ending is that many of the neophytes joined local 776 and learned that they had a right not to be exploited again. Gale Hurd, you’re already a rich kid. Do you have to make craft people mess up their lives to make you richer? Jim Cameron, we know you’re a macho man, and yes, the people you hired are not as tough or as smart as you. But they are ostensibly professionals. That means they do their jobs for a lot of movies. Your movie does not, can not mean life or death to them as it does to you. Didn’t you learn anything from the tragedy on John Landis’ Twilight Zone? Well, it’s over. And not one sound editor drowned.

—DS

Sc. 11 Opinion: Credit for Movie Sound Workers

Film students may not yet understand the business of a production’s bestowing or a worker’s receiving proper and fair credit for their work. In the world of student and low-end independent production, the placement of up-front credit graphics and below-the-line credits on a movie crawl may be the only payment for voluntary work. Students seem to understand the value of professional credits on mainstream films, as they are keenly conscious of what it may take to establish a career. But it is possible that students imagine professional credits to be given as generously as they are in the student/indie world, when in fact printed credits are the result of individual contracts and collective-bargaining agreements. Somewhere behind every mainstream film credit lies the work of lawyers, agents, and bureaucrats.

A Note about the Internet Movie Database

It is the belief of many students and movie fans that credits displayed on the IMDB are gospel or empirically verifiable fact, but the IMDB is a child of the internet, a sibling to Wikipedia, and not exactly the vade mecum of film history. Along with our peers in the film school instruction business, the author frequently calls upon the IMDB for quick contextual reference during lively discussions. And like our peer post sound professionals, the author often chafes at the seemingly immutable misinformation abiding in it. But these mistakes are forgivably rare, comprising in the author’s case two or three film titles7 we never heard of, let alone worked on.

It should become more widely understood that the IMDB evolved in the earliest days of home video (VHS and Beta tape cassette formats here in the U.S.) when corner video rental shops were proliferating. The most probable history (which may be apocryphal) of its birth is the story that the British programmer who designed it was responding to some active online discussions, before the existence of the World Wide Web (it would have been on the bulletin board BBS systems of that period) between a few British film fans who simply transcribed credits by hand from the rented tapes on their VCRs. One version of the story has the initial seeds of the project generating from friendly arguments over who they thought were some of the “hottest” female stars of the 1940s and ‘50s. History, as is often the case, turns on such mundane events.

In the U.S., the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (A.M.P.A.S.) has begun a database of motion picture credits, which may be considered a more verifiable source than the IMDB. Run by the research people at the Academy’s Margaret Herrick Library, the Index to Motion Picture Credits trades off some lack of comprehensiveness in favor of absolute accuracy. All of these credits (there seem to be tens of thousands) come from vetted submissions for Academy Awards® consideration. Scholars outside of Los Angeles can take advantage of its accessible web page, but as of this writing, the records only work back to 1952. The Academy has a limited number of researchers at work. It should be understood by scholars of movie sound (as Ben Burtt has often noted) that the first century of Hollywood filmmaking saw Sound credited largely to the administrative heads of studio sound departments (such as the innovative Douglas Shearer, since the earliest days of movie sound), sometimes also to production mixers (with a variety of credit titles) or for other technological contributions to sound.

Editorial: Eighty-One Out! Published July, 1990 (Vol I #13)

Sc. 12 Editorial: Eighty-One Out!

The closing credits of Gremlins 2 omitted many names. Warner Bros., in their limitless legalistic wisdom, found reasons why every individual could not be acknowledged.

Director Joe Dante and Producer Mike Finnell personally took a full-page ad in Variety, in which they thanked eighty-one such individuals. Included were Bruce Botnick, who recorded the music, Tim Webb and Mike Haney, who handled the rerecording stage’s machine room, Foley artists John Roesch and Ellen Heuer, Ezra Dweck who recorded new sound effects, and the sound editing assistant team: Josie Nericcio, first assistant, and Oscar “Omit” Mitt, the second assistant. The logistical keystone of the sound editing process was the most glaring omission from the film’s sound credits: first assistant Sonya “Sonny” Pettijohn. A tip of the MSNL hat also to Demon Librarian Steve Lee and Special SFX designer John P.

Joe Dante and Mike Finnell have a high regard for the people who help make their movies, and have with their ad set an ethical example for other directors and producers to follow.

—ed.

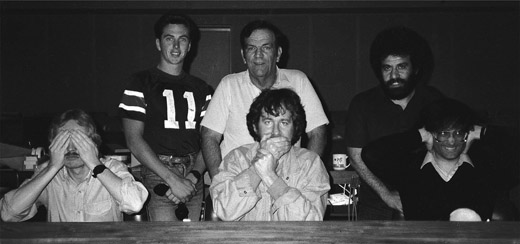

Standing at the Warner Hollywood Studios Stage D console, Gremlins (1984) Mixers Kevin O’Connell, Bill Varney, and Steve Maslow. Sitting: Producers Mike Finnell (see no evil) and Steven Spielberg (speak no evil) with Director Joe Dante (hear no evil). Collection of Kevin O’Connell.

Sc. 13 Thoughts from the Foley Stage

MSNL contributors and readers were witness to the slowly growing recognition of Foley and its mitosis apart from the other sound effects crafts. In an alternate universe, had they been formally represented by one of the Hollywood trade unions, the process may have moved a lot faster. Foley artists struggled for years to attain union representation. Another example of a new specialization born in the late decades of the twentieth century, it took nearly a generation of them working full-time to be recognized as a craft completely independent of sound editing. Much of this is discussed in Prof. Ament’s book The Foley Grail (the title was initially used in her Moviesound Newsletter pieces). Issues about pay and working hours would arise only as more soundtracks depended upon the new idea of “full Foley” through the 1980s. Foley had previously been an enhancement to soundtracks, but not a full-time job.

Warner-Hollywood Studios Foley stage, c. 1986–7, during post-production work for The Rosary Murders (1987) Photo by Vanessa Theme Ament.

Union representation was one struggle. Credits were another. The Index to Motion Picture Credits still does not list Foley Artists as a separate craft, though students will find them on the IMDB wherever films have them credited. But there has not been a rule incumbent on production companies to offer Foley artists and Foley mixers any screen credit, only the benevolence of producers, directors, or supervising sound editors willing to ask for it or fight for it. Studios have callously ignored some categories of post-production workers, because each line in the printed crawl costs them money.

In the 1980s, full-time Foley Artists were a small community, who set their suggested pay rates only by mutual consent. Unrepresented legally, it was only their cohesion as a social community that assured their daily rates. Freelance workers in competition may be easily exploited, as they are in independent film-making. Word-of-mouth kept the Foley Artist community somewhat in solidarity and at a distance from the exploiters, and consequently was able to elevate the craft to a professional level. They successfully achieved, for instance, the conversion of their scheduled night sessions from eight hours to six hours work for eight hours of pay. Supervising Sound editors routinely argued with parsimonious line producers that those six night hours provide much more productivity. Without the distractions of telephone calls, visiting editors, and lunch hours out of the studio stretched by Los Angeles traffic, Foley artists, Foley mixers, and Foley Recordists all worked nights with unprecedented focus and efficiency. Thus the working culture established new rules without the benefit of a legal collective bargaining agreement but with the benefit of strong social consensus.

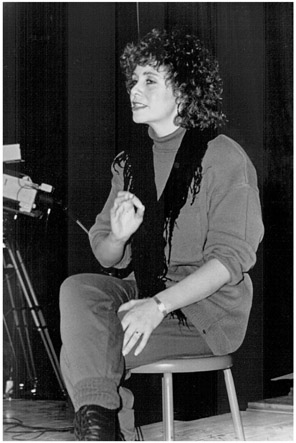

Vanessa Ament leading a discussion about Foley and post Sound at the Denver International Film Festival, 1989. Photo by Larry Laszlo.

Over the many years of Foley’s ascent to professional status in the industry, efforts were made and frustrated to attain representation by the Screen Actors’ Guild, The Directors’ Guild, The American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, and The Motion Picture Editors’ Guild. Even the Motion Picture Sound Editors’ Golden Reel award, given annually to a number of feature film and television sound crafts categories, had largely ignored Foley. After extensive advocacy by Vanessa Ament, the MPSE began to award Foley artists with a citation certificate (but not their statuette, which went only to editors) for certain film and TV titles. Eventually, the Editors’ Guild (IATSE Local 700) admitted Foley artists into full membership, which began their working under the legal collective bargaining contract attained by their film and sound editing peers.

Editorial: The Foley Grail Published April–May, 1991 (Vol I #18)

Sc. 14 Editorial: The Foley Grail

Many American households were tuned in to the Academy Awards® broadcast in March. The good news is that the viewers were able to watch Cecelia Hall and George Watters receive the Oscar® for sound effects in The Hunt for Red October (see MSNL #12.) As we have pointed out, sound effects does not receive an Oscar® every year, and this one was certainly well-deserved. The not so good news is that once again the Foley artists who created a large portion of the sound effects were never acknowledged while all the sound, dialogue, A.D.R. and Foley editors were publicly thanked. Only twice during the ceremonies have the Foley artists been included in Academy thank-you’s. In his acceptance speech for E.T., Charles Campbell thanked John Roesch and Joan Rowe. Last year, Ben Burtt and Richard Hymns thanked Dennie Thorpe for her work on Indy 3.

Sound effects are gaining public recognition, and we don’t intend to squelch their appreciation. We at MSNL are the first to champion the right of sound editors to get their deserved kudos. Rather, it is our intention to also champion another cause: the usually terribly underplayed contribution of the Foley artists who have created footstep character for the actors, enhanced the use of props and clothing movement, as well as substantially augmented the environmental and special effects sounds that in the past have only been in the editor’s domain. Simply put, as the Foley artist has gained more responsibility for the final soundtrack, it is only appropriate that s/he share in the recognition.

Sound editors often complain that they feel underappreciated by picture editors. The sentiment is that sound editors are treated like poor cousins although their talents and skills are called upon in many more creative and integral ways than previously. It is easy to overlook the growth and sophistication that a craft has undergone in the hub-bub of putting a complex film together. However, Foley artists have the same universal complaint about sound editors. Perhaps it is time the post-production film community reassess its process for completing a film and give credit where credit is due.

Congratulations to David Fein and Ken Dufva for outstanding Foley in The Hunt for Red October.

—VTA

Notes

1. A vine appeared after this chapter was written, which has Welles as the steely-eyed, dictatorial Kane applauding for his wife’s dismal operatic debut. The heavily charged handclaps make a perfect film loop cycle.

2. Shot inexactly at around 16 frames per second and played back routinely at 24, the newly standardized sound speed, these pictures should have been “step-printed” to add frames and at least come closer to the original speed of the action.

3. One of the first aesthetic casualties of television and video was the cinematographer’s art of composition. Film exhibition in widescreen was itself an effort to entice audiences away from their televisions throughout the 1950s. Cinemascope, VistaVision, Todd A-O, Cinerama, and other spectacularly wide formats offered immense visual relief, along with color, to filmgoers bored with the 1:1.33 (a.k.a. “4x3”) TV rectangle (which had been based on the traditional aspect ratio of Hollywood movies). Movies shot in widescreen and shown on television absolutely destroyed visual composition.

4. Many local projectionists had repaired broken reels of film poorly, or become self-appointed censors, or at least responded to the reckless injunctions of church groups and theater owners, early in film history.

5. Did MSNL fail to credit the great director Robert Wise? Shame on us.

6. Snow White and the Seven Dwarves was released in 1937 and must have been in production for three to five years before that. An animated feature-length film rival was Max and Dave Fleischer’s excellent Gulliver’s Travels, released in 1939. It probably overlapped Snow White in its production schedule, and must have employed hundreds of cell painters; presumably the work was not done in Los Angeles, but in the Fleischers’ Florida studios.

7. Personal notes: In the cases of Steel Dawn (1987) and Appointment with Fear (1985), my mistaken IMDB credit may have deprived another fellow with our obviously common name from a well-deserved credit. As to the first title’s credit, I have never mixed sound for an entire film, and as to the second, you wouldn’t want me even trying to hold a boom for two minutes. In the case of Options (1989), which looks to be a modest but pleasant comedy, I have possibly developed a case of professional amnesia. I don’t remember ever seeing this picture.