Chapter 5: Dealing with Diabetes Restaurant Eating Dilemmas

Today many people who eat restaurant meals have concerns about their health and nutrition. It’s become commonplace to ask questions and make special requests. However, as a person with diabetes or a diabetes caregiver, you’ll deal with dilemmas and challenges in addition to unhealthy foods and ingredients, and large portions. This chapter offers guidance on three diabetes-specific dilemmas: delayed meals, alcohol consumption, and sweets and desserts.

Delayed Restaurant Meals

When it comes to restaurant meals, expect the unexpected. That’s tough for people with diabetes, especially when it comes to the potential risk of hypoglycemia. But, it’s the reality you’ve got to deal with. A restaurant might have lost your reservation or might not be able to seat you quickly, your meal-mate(s) might be late, the kitchen might be slow, there may be a mixup with your order, or your order might not come out right. And, as you know, the list of possible issues goes on. Your modus operandi should be, “better to be safe than sorry.”

A big challenge, if you take one or more blood glucose–lowering medication that can cause hypoglycemia, is how to manage delayed meals. For example, if you usually eat lunch between noon and 12:30 pm, and you take a mixture of intermediate-acting and rapid-acting insulin before breakfast, what steps can you take to safely delay your meal until 1:00 or 1:30 pm when your friends or business associates want to eat? Or what should you do if you want to dine at 8:00 pm on a Saturday night, when your usual dinner time during the week is 6:30 pm?

Blood Glucose–Lowering Medications and Delayed Meals

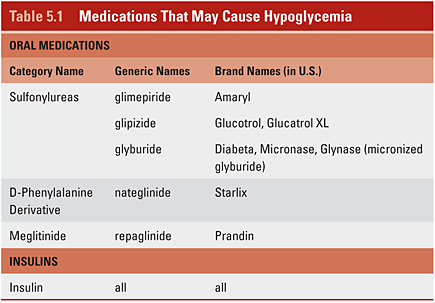

All types of insulin can cause hypoglycemia, as can a couple of categories of oral medications (see Table 5.1). If you take one or more of these medications, you’ll need to put a game plan in place to deal with delayed meals.

• Insulin: Everyone with type 1 diabetes takes insulin, as do millions of people with type 2 diabetes. These days, people typically take two types of insulin, either separately or in combination.

* Long-acting and rapid-acting insulin: Many people take one of the two currently available longer-acting insulins, such as detemir (Levimer) or glargine (Lantus), once or twice a day, either in the morning or before bed or at both times. Then they take one of the three rapid-acting insulins prior to eating. The rapid-acting insulins are: lispro (Humalog), aspart (Novolog), and glulisine (Apidra). These must be given as separate shots because the insulins can’t be mixed. These insulins can be taken using a pen, a patch (these are newer devices, such as V-Go or PaQ), or, the old-fashioned way, with vial of insulin and a syringe. People who use an insulin pump use only one type of insulin. Most often that’s rapid-acting insulin, but sometimes slower-acting U500 insulin is used. If you use rapid-acting insulin to manage the rise of glucose from meals (food), you can delay taking a dose until about 15 minutes before you eat your delayed meal (but follow what you know best keeps you safe). For pointers on using rapid-acting insulin with restaurant meals read the practical tips in this chapter.

* Pre-mixed insulin combinations: Some people take pre-mixed combinations of two types of insulin. These come in various ratios. Typically it’s a mixture of an intermediate-acting insulin (NPH) with a rapid-acting or short-acting insulin (Regular). The ratios for pre-mixed insulins range from 50% of each insulin to 70–75% of intermediate-acting insulin and the remainder (30–25%) of the rapid-acting or short-acting insulin. Typically people take two shots a day; one in the morning and one before dinner. A disadvantage of these insulin regimens is that they do not allow much adjustment of dose or flexibility in meal times. If you use one of the pre-mixed combinations, you’ll need to have a game plan to avoid hypoglycemia with delayed meals. If you find you regularly need more flexibility in your schedule, talk to your health-care providers about getting on a more flexible insulin regimen than pre-mixed dosing.

• Oral medications: Medications in the sulfonylureas category and the pills Prandin (repaglinide) and Starlix (nateglinide) can cause hypoglycemia (see Table 5.1). These pills work by making the pancreas put out more insulin. The sulfonylureas, which are taken once or twice a day, lower glucose more slowly than Prandin and Starlix. If you take a sulfonylurea, you’ll need to pay attention to your meal times and possibly put an action plan in place for delayed meals.

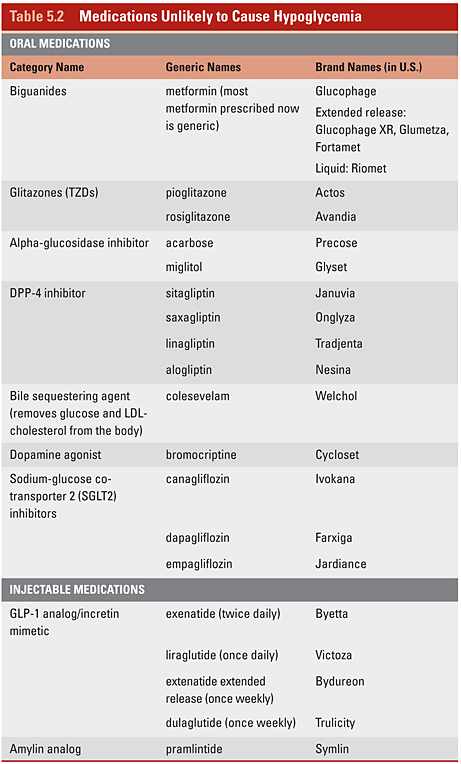

One positive aspect of the management of diabetes today is the availability of a slew of new oral blood glucose–lowering medicines (pills) and new types of insulin and other injectable medications that better mesh with the realities of life in the 21st century. Another big plus, as you’ll see in Table 5.2, is that many of these newer medications aren’t likely to cause hypoglycemia, even if you delay a meal. This can allow you the flexibility to manage your diabetes in the manner that best suits your needs and lifestyle. If your current blood glucose–lowering medication regimen is not in sync with your life schedule or style, speak up. Do the same if you aren’t meeting your glucose and A1C goals (see the table in Chapter 2). Learn about other glucose-lowering medications. Then talk with your health-care providers about your lifestyle and medication options. Don’t wait for them to ask you.

Have an Action Plan to Prevent Hypoglycemia

If you need to delay a meal and you take a glucose-lowering medication or a type of insulin that has the potential to cause your blood glucose to get too low, put a preventive action plan in place using the following guidelines:.

• Check your blood glucose at the usual time of your meal.

* If your blood glucose is high (>130 mg/dl), you can wait a short time before you eat without concern. But do check again if you develop symptoms of low blood glucose before your meal.

* If your blood glucose is around your premeal goal (70–130 mg/dl is the American Diabetes Association goal) and you feel it will fall too low before you get to eat, eat some carbohydrate (start with 15 grams) to make sure your blood glucose doesn’t go too low before your meal.

* If your blood glucose is lower than 70 mg/dl and/or you feel the symptoms of low blood glucose, then you can use 15 grams of some source of carbohydrate that you carry or is accessible to you, such as glucose tabs, gels, sugar-sweetened soda, or juice, to treat your hypoglycemia. Try to eat your meal soon after.

• If you delay your meal more than one hour and your blood glucose is around your premeal goal, you may need to eat more than 15 grams of carbohydrate to keep it from going too low before your meal. Then you may want to eat fewer grams of carbohydrate at the meal when you finally eat.

• Keep easy-to-carry and quick-to-eat foods that contain carbohydrate or a source of glucose, like tablets, gels, or liquid, in places such as your desk, briefcase, purse, locker, glove compartment, night stand, and any other places you may need it. These can come in handy with delayed meals or any time your glucose may be getting too low. A few suggestions for nonperishable foods to carry are: dried fruit, cans of juice, pretzels, lifesavers, gumdrops, gummy bears, or snack crackers. Try out a few items and learn what works best for you in a variety of situations. Check the Nutrition Facts label on the food to determine the serving size equivalent to 15 grams of carbohydrate.

These suggestions offer you general rules of thumb. Check with your health-care providers to learn the best alternatives for you based on your diabetes goals and the types of medication you take.

Practical Tips for Using Rapid-Acting Insulin with Restaurant Meals

Rapid-acting insulin came on the market in the mid-1990s. Prior to its availability, Regular (short-acting) insulin was the quickest acting insulin available. Though it’s called “rapid-acting” insulin and health-care providers initially encouraged people to take it right before eating (the advertisements still advise this for regulatory reasons), for most people it doesn’t get absorbed or lower blood glucose as quickly as you’d like it to. Today, diabetes experts agree that rapid-acting insulin doesn’t really start lowering glucose for a good 15–30 minutes after taking it. The maximum blood glucose–lowering effect of rapid-acting insulin occurs more often in the range of 90–120 minutes after it’s injected rather than around an hour after injection. People who wear a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) have made these observations as well.

Taking rapid-acting insulin 10–15 minutes before you eat and carefully calculating your dose according to the grams of carbohydrate you’ll eat is ideal for blood glucose control. However, this isn’t always possible and restaurant meals present a common challenge with dosing rapid-acting insulin. If you take rapid-acting insulin when you start to eat, or perhaps during or after eating, and find that your glucose rises quickly after you eat, then you may want to try to take at least some portion of your premeal insulin dose about 10–15 minutes before you eat and then take the rest of the dose once you know how much you’ll eat. In general, the best thing to do is test out what works best for you in various situations, with the goal of preventing hypoglycemia.

These practical tips can help you achieve better glucose control after eating a restaurant meal. Several of these suggestions are easier to implement if you wear an insulin patch or pump because, with these devices, no additional injections are necessary. Discuss these suggestions with your health-care provider. Your safety is top priority!

• High blood glucose before a meal: If you have high blood glucose prior to your meal, take some rapid-acting insulin about a half hour before your meal to give the insulin time to get your glucose coming back down. It might take longer than the time you have before you eat to come down, but at least it will be on the downswing.

• Uncertain carbohydrate intake: If you don’t know how much carbohydrate you will eat at a meal or you don’t quite know how fast the restaurant meal will be delivered, consider splitting your rapid-acting insulin dose. Take enough insulin 15 minutes before the meal to cover the minimum amount of carbohydrate that you know you will eat (say 30–45 grams) and to keep your glucose from rising high. Then, as the meal goes on and you know how much more carbohydrate you will eat, take the remaining amount of insulin you need to cover the carbohydrate.

• Long, lingering meals or food events: Pump users who plan to have a long, lingering meal (say at a cocktail party or celebratory event) or are eating a meal that is high in fat may want to use the bolus delivery tool that allows you to extend a bolus dose over an hour or more.

Most importantly, learn from your experiences. There is a large variation in individual blood glucose responses to food and insulin among people with diabetes. The more you check your glucose after eating and observe changes, the more you will learn and be able to fine-tune your control. Keep notes of your responses to various foods and activities. Everyone is unique. Create your history based on your unique experiences.

Alcohol—When, What, and How to Drink Safely

Restaurant meals are a common time to consume alcohol. Drinking alcohol can present a couple of dilemmas for people with diabetes. The number-one dilemma is the risk of hypoglycemia with excess alcohol consumption, especially if you take a blood glucose–lowering medication that can cause hypoglycemia, like insulin or a sulfonylurea (see Table 5.1). Dilemma number two is the challenge of excess calories from alcohol. All things considered, moderate consumption of alcohol, believe it or not, has health benefits. But excessive alcohol consumption can derail your eating plan and even endanger your health. Learn more about alcohol’s health benefits and pitfalls, the calorie and nutrition profile of alcoholic beverages, and tips to limit excess calories in Chapter 9.

Alcohol and Hypoglycemia: Preventive Steps

For people with diabetes who take insulin and/or a glucose-lowering medication that can cause hypoglycemia, excess alcohol intake can cause hypoglycemia up to 24 hours after it is consumed. For example, if someone has several alcoholic beverages at a special celebration one evening, hypoglycemia can occur shortly after drinking or in the wee hours of the night. Practice hypoglycemia prevention with these steps:

1) Limit excess alcohol intake.

2) Check glucose levels often when drinking alcohol, especially before going to sleep. If necessary, consume some carbohydrate-containing food before going to sleep.

3) Consume some source of carbohydrate, in the form of snacks or as part of a meal, along with the alcoholic beverages to keep your glucose from becoming too low. Never drink on an empty stomach.

How to Count Alcoholic Beverages in Your Eating Plan

Over the years the answer to the question, “How should I factor alcohol into my eating plan to account for the calories?” has changed. Today, the answer, according to the American Diabetes Association, is that you can drink a moderate amount of alcohol without making changes to your eating plan. You don’t need to omit foods to account for the alcohol. However, if you drink a moderate amount of alcohol daily and your weight is a concern or you want to lose weight, you’ll need to determine how many calories you can allot for alcohol. If any of your alcoholic beverages contain grams of carbohydrate from calorie-containing mixers, you need to count them.

Tips to Drink Alcohol Safely with Diabetes

• Check your blood glucose to help you decide whether you should drink and when you need to eat something.

• Don’t drink when your blood glucose is below 70 mg/dl and/or you have symptoms of hypoglycemia.

• Remember that alcohol can cause low blood glucose hours after you consume alcohol (see Alcohol and Hypoglycemia: Preventive Steps above).

• Wear (preferably) or carry identification that states you have diabetes. Keep in mind that signs of hypoglycemia can be mistaken for being drunk.

• Don’t drink on an empty stomach. Munch on a carbohydrate source (popcorn or pretzels) as you drink or wait to drink until you get your meal.

• Do not drive for several hours after you drink alcohol. Never drink and drive.

Sweets and Desserts

Nearly everyone has a sweet tooth or two! We’re born with an innate desire for sweets. You don’t all of a sudden lose your desire for sweets when you’re diagnosed with diabetes. Granted, some people like (some would even say “need”) sweets more than others. The advice for people with diabetes, historically, was no sweets or sugary foods. That is no longer the recommendation from the American Diabetes Association; in fact, that hasn’t been the advice about sweets for people with diabetes for a couple of decades.

The current Nutrition Therapy Recommendations for the Management of Adults With Diabetes from the American Diabetes Association suggest that if you want to integrate a small amount of sweets into your healthy eating plan, you should substitute these for other foods that contain carbohydrate. In small amounts and only eaten on special occasions, sweets won’t affect glucose or blood fat (lipid) levels. The amounts of sweets you choose to fit into your eating plan and how frequently you indulge will need to depend on your weight status and your glucose and lipid levels. It also depends on whether or not you use a blood glucose–lowering medication, like rapid-acting insulin, that you can take more of to compensate for the extra carbohydrate load from desserts. But do be careful of excess calories and weight gain. Talk to your health-care provider about how to fit sweets into your meal plan.

Sweets and desserts certainly make their appearance on all types of restaurant menus, from fast food to fine dining. It may be a fried apple pie, a brownie, or cookies the size of your face. At coffee shops there are breakfast pastries, donuts, and more. Most ethnic restaurants serve up the favorite sweet treats of their cuisine—think baklava in Middle Eastern restaurants and cannoli in Italian restaurants. You’ll see that dessert draws little attention in some cuisines, like Japanese and Chinese. Then there are fine dining restaurants where an award-winning pastry chef may be on staff to whip up delectable desserts. Sugary foods that aren’t desserts show up on menus as well, from a long list of sugar-sweetened beverages, to those more-prevalent-than-ever smoothies and sugar-laden sauces and syrups, such as maple syrup, barbecue sauce, and ketchup, to name a few. You’ll find information and guidance about desserts in the chapters in Sections 2 and 3.

When it comes to choosing the sweets you eat, here are two essential bits of advice. One, eat them in small portions. Two, make sure each and every morsel quenches your sweet tooth to the max. The more satisfied you are from a small amount of sweets, the easier time you’ll have following a healthy eating plan. Here are some other healthy eating tips and tactics for sweets and desserts:

• Prioritize your personal diabetes and nutrition goals. Which are most important to you and your health: blood glucose control, blood lipid control, and/or weight loss or maintenance? Your priorities should dictate how you strike a balance with sugars and sweets.

• Think about a few of your very favorite desserts, those that are mouthwatering to you! Think about where and when you eat these (perhaps you prepare and serve them at home or eat them on a special occasion or holiday). Decide how often you can eat them and how you can fit them into your healthy eating plan.

• It may be best for you to keep sweets and desserts out of your home (if possible, based on who else you’re living with) and just plan to enjoy them at an occasional and special restaurant meal.

• In ice cream and yogurt shops, don’t think kiddie- or junior-size servings are just for kids. Think of them as portion-controlled sizes for calorie and carbohydrate counters too.

• If you want a topping for your small serving of ice cream or frozen yogurt, go for nuts, fresh fruit, raisins, or granola. Steer clear of the toppings made from chopped-up candy.

• Order one dessert and two (or more, depending on the number of diners) spoons or forks. Quite often just a few bites of a fantastic dessert will quench your sweet tooth.

• Can’t find anyone to share with? Split it! Eat a portion of your dessert and take home the rest. But practice that “out of sight, out of mouth” tactic. Set aside the portion you’ll take home before you dig into the rest.

• Looking for the nutrition information for desserts, particularly calories and carbohydrate, total fat, and saturated fat grams? In Sections 2 and 3, at the end of most of the chapters, you’ll find the nutrition information for some sweet treats in the Health Busters and Healthier Bets tables. If you’re determined to find the nutrition information for desserts from your favorite ethnic and fine dining restaurants, do some extrapolating from websites and online recipes or recipe books loaded with nutrition information. Then put your guesstimating skills into action.

• When you do eat sweets, check your blood glucose 1–2 hours later to observe your body’s response. Do this repeatedly because different sweets will impact your glucose differently at different times.

• Keep an eye on your A1C (your average glucose measure over the past 2–3 months) and your blood fat (lipid) levels to see whether eating more sweets affects these numbers.

• Keep an eye on that scale. Excess sweets and desserts can make holding the line on your weight or losing weight more challenging.

Blood Glucose–Lowering Medications

Many people with diabetes, type 1 or 2, take several types of medications. One or more of these medications may be used to lower blood glucose. Others may reduce the risks of heart disease by lowering bad cholesterol or treating high blood pressure. Prior to 1995, there were only two categories of glucose-lowering medications to treat type 2 diabetes—sulfonylureas, like glyburide and glipizide, and various types of insulins. Much has changed since then! During the last couple of decades a number of new categories of these medications have been approved and added to the choices your health-care providers have to help you keep your glucose levels in control.

What’s particularly good news about these newer blood glucose–lowering medications is that most of them are unlikely to cause hypoglycemia, due to the way they work (unless they are taken with other medications that can cause hypoglycemia). It is common for people with type 2 diabetes to take more than one medication to lower blood glucose. This may mean two different pills or taking one pill that combines two categories of blood glucose–lowering medicine. Or you may take one or more pills and/or an injectable medicine, like insulin or a GLP-analog. It may be that one of the medications you take can cause hypoglycemia and another is unlikely to do so. Or it may be that none of the blood glucose–lowering medications you take may cause hypoglycemia. Learn the actions of the medications you take from your health-care providers, including your primary care provider, diabetes educators, or pharmacists and determine whether any of them put you at risks for hypoglycemia.

Several of the diabetes restaurant eating dilemmas detailed in this chapter revolve around how to stay safe. This mainly involves how to prevent or, if you experience it, treat hypoglycemia. It’s important to know which glucose-lowering medication(s) you take and whether or not any of them put you at risk of hypoglycemia. Tables 5.1 and 5.2 list the blood glucose–lowering medications currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and available on the U.S. market. Keep in mind, these days, this is changing rather frequently.