Chapter 9: Healthy Drinking Out: Nonalcoholic and Alcoholic Beverages

Your focus when you eat a restaurant meal is typically on the food; however, the type of beverage you choose and the amount you drink is another aspect of restaurant meals you need to deal with, whether you’re staring at the menu board in a fast-food restaurant or sitting down for an upscale meal. Yes, meals are typically partnered with a beverage or two. Your beverage choices, both nonalcoholic and alcoholic, deserve as much thought as your food choices. Beverages have the potential to dramatically escalate the calories in a meal . . . or not. Learn all about nonalcoholic and alcoholic beverages and how to order them wisely in this chapter. Specific guidance on drinking alcohol safely with diabetes is outlined in Chapter 5.

Nonalcoholic Beverages—Challenges and Choices

From fast-food burger-and-fries chains to coffee, bagel, and sandwich shops and walk-up-and-order ethnic restaurants, the thirst quenching options have exploded and sizes have grown. Healthy and less-than-healthy beverages abound. Water, from the tap or bottled, is no longer hard to find. Thank goodness, because it’s often the healthiest bet! Many of these restaurants serve both sugar-sweetened and diet sodas (carbonated soft drinks), either from the fountain or in bottles. Drinks from the fountain are typically available in at least three sizes, starting with small (which may well be relatively large at 16 ounces) and going up to large, or even extra-large or larger (in excess of 30 ounces). If restaurants stock bottled or canned beverages, they usually have an array of options, from water to fruit juice, sports drinks, teas, coffees, or sodas. Sometime there’s a choice of sugar-sweetened or diet. The sugar-sweetened beverages can pack in a load of carbohydrate grams and calories, yet offer nearly nil nutrition. If you want a hot beverage, most of this ilk of restaurants is at the ready to serve you a variety of coffees or teas, from the basic brew to the specialty types.

In the wide variety of sit-down restaurants, your meal often starts with a complimentary glass of water. But the first question the waitperson asks is typically, “What can I bring you to drink?” The nonalcoholic beverage options usually range from soda (both sugar-sweetened and diet) to milk, fruit juice, coffee, and tea.

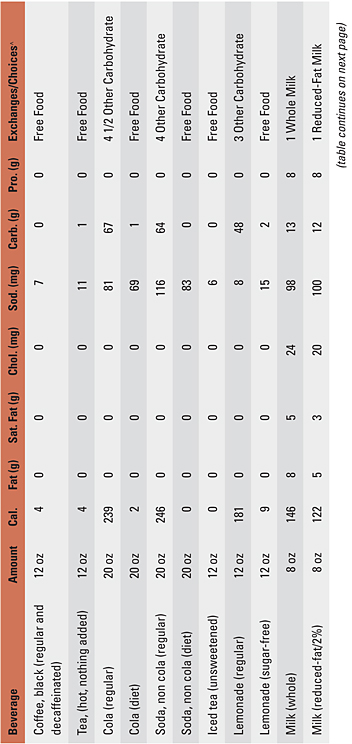

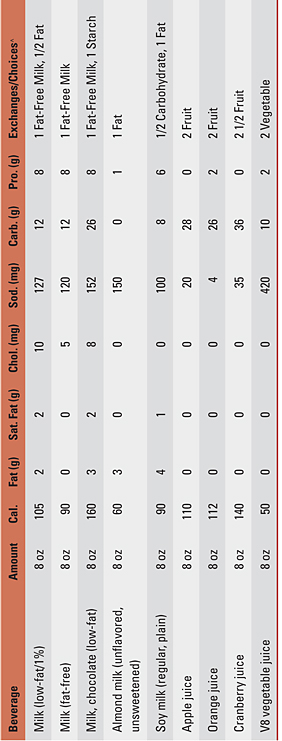

Regardless of the type of restaurant foods you eat, the more drinks you pay for, the more the restaurant likes it, because you’ll run up your bill on items that require minimal labor to serve. Making health- and calorie-conscious nonalcoholic beverage choices can assist with weight and diabetes control . . . and keep more money in your pocket. Similar nonalcoholic beverages are served in most restaurants. Table 9.2 at the end of this chapter contains key nutrition information for these beverages.

*Consider the nutrition information for these beverages as an estimate and not specific for the actual restaurant beverage you drink. Use specific information from the restaurant serving the beverage when it is available.

∧Calculated based on the information provided in American Diabetes Association and Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Choose Your Foods: Food Lists for Diabetes, 2014.

Nutrition and Diabetes Concerns

Before digging further into nonalcoholic beverages, here are a few of the health, nutrition, and diabetes-related concerns surrounding nonalcoholic beverages.

Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Epidemics—The Beverage Factor

Yes, there’s a strong correlation between the increase in availability, over the last few decades, of the types of beverages that contain added sugars (without much nutrition) and the increasing sizes of these beverages, and the expanding waistlines and high incidence rate of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, released by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Americans consume about 16% of our calories in the form of all sources of added sugars. That’s an average of 300–400 calories or 21 teaspoons of added sugars per day! Over a third of these calories are contributed through sugar-sweetened sodas, energy drinks, and sports drinks. The wider-than-ever variety of beverages like specialty coffee drinks, sweetened iced teas, and those thick smoothies, in large servings, contribute to this problem as well. Americans are sipping and slurping lots of calories without much nutrition bang. That’s why a key principle of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans is a focus on reducing the intake of added sugars from beverages in order to tighten our calorie-intake belts and hopefully our waistlines.

The easiest way to limit those added sugars (which are all grams of carbohydrate) and calories is to consume fewer and smaller portions of sugar-sweetened beverages—or none at all. People with diabetes who are monitoring grams of carbohydrate generally don’t have enough carbohydrate grams to spare on beverages with added sugars.

Chew Calories, Don’t Sip Them

Nutrition experts continue to debate whether people consume calories more easily if they’re sipped or slurped rather than chewed. When you think about it, it stands to reason that taking the time to chew solid foods, especially sources of carbohydrate, from vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and more, will be more satisfying than quickly and easily sipping them. Typically speaking, a beverage—say a 20-ounce sugar-sweetened soda at 250 calories—can be consumed much more quickly than a small, yet high-volume entrée salad with various ingredients and the same number of calories. And again, you should think about nutrition. High-calorie beverages with added sugars are light on nutrients and much needed fiber. Word to the wise: Chew your calories, don’t sip them.

What About High Fructose Corn Syrup and Diabetes?

There are many names for the calorie-containing sweeteners or added sugars used in our foods today. The main sweeteners used in sugar-sweetened beverages are high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) and sucrose from cane or beet sugar. HFCS is a corn-based sweetener that is a blend of glucose and fructose. The blend varies from 42–55% fructose, based on the product. Sucrose, like HFCS, contains equal parts glucose and fructose. Though there have been a number of studies in this area to date, the human studies, though short term and small, consistently show no different impact on measures of health when HFCS or sucrose is consumed compared with other types of sugars. The most recent American Diabetes Association’s Nutrition Therapy Recommendations for the Management of Adults With Diabetes contains a strong statement suggesting you limit or avoid sugar-sweetened beverages from any calorie-containing sweetener, including HFCS and sucrose, if you want to reduce weight gain and prevent increasing your risk for cardiovascular disease. The recommendations also note that consuming a small amount of fructose naturally occurring in foods like fruit is unlikely to raise triglycerides. High triglycerides can be a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

What About Sugar Substitutes and Diabetes?

The safety and effectiveness, when it comes to assisting with weight control, of sugar substitutes seems to always be a hot topic because of the potential for an increased use of these products by people looking to limit sugar, carbohydrate grams, and calories. According to the American Diabetes Association’s Nutrition Therapy Recommendations for the Management of Adults With Diabetes, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—the agency responsible for reviewing the safety of sugar substitutes in the U.S., both initially and over time—has approved seven sugar substitutes for the general public, which includes children and people with diabetes. The major approved sugar substitutes include, in chronological order of approval, saccharin, aspartame, acesulfame-k, sucralose, and stevia-based sweeteners. The most common sugar substitutes found in restaurants contain saccharin, aspartame, sucralose, and stevia. These sweeteners do not, the American Diabetes Association notes, cause a rise in blood glucose unless they are used in foods that contain other nutrients that raise blood glucose—think yogurt, hot cocoa, or fruit cups.

When it comes to their effectiveness in weight control, the American Diabetes Association and other organizations conclude that the jury is still out on whether the use of sugar substitutes assists with long-term weight control. It’s not that the research shows that sugar substitutes increase appetite, hunger, or cravings, which has at times been the accusation. The challenge with these products is that when people use beverages or products sweetened with sugar substitutes, they often then eat additional calories to compensate for the calories saved. The American Diabetes Association, other organizations, and nutrition experts conclude that the wise use of sugar substitutes, whether in beverages like diet soda or in other foods, can be part of a comprehensive and successful weight-control plan as long as (this is important!) you substitute the beverage or food containing a sugar substitute for a sugar-sweetened food.

How Much to Hydrate

For many years, experts preached the guideline of 8 ounces, eight times a day for beverages, but this guideline no longer holds water. In 2004, the Institute of Medicine (IOM), a government health advisory organization, offered an update. The IOM report suggests that fluid needs vary widely from person to person. They vary based on climate and food choices. Most people, the guidelines suggest, can stay hydrated by letting thirst be their guide. When it’s warm outside or you are participating in an activity that is causing you to sweat, drink more to stay hydrated. Their general recommendation for fluid is 91 ounces a day for women and 125 for men—about 11 and 16 (8-ounce) cups of liquid for women and men, respectively. The IOM didn’t specify how much of the fluid should come from water versus other beverages and foods. (Don’t forget that vegetables and fruits contain a good bit of fluid, so the more of these you eat, the more fluid you get.) The panel did note that both caffeinated and noncaffeinated beverages can provide the necessary fluids.

Nonalcoholic Beverage Categories

As you see, with all of these nonalcoholic beverage options, your answer to the question “What do you want to drink?” deserves some healthy contemplation.

Water

Water is likely the healthiest drink in town. It is calorie free, a helpful hydrator, inexpensive (if you drink it from the tap), and plentiful (at least for the moment). When it comes to restaurants, water, either from the tap or bottled, is very accessible. You can purchase a bottle of water in most restaurants that offer a bevy of bottled beverages. In restaurants that rely on fountain drinks, there’s usually a spigot you can press for water and they’re glad to give you a cup to do so for free. It may be a mini cup, but you’ll burn a few calories getting refills. Most sit-down restaurants offer water upon request. In upscale restaurants, they’ll pour you a glass, too. Rebuff the offer of bottled flat or sparkling water if you don’t want to pad your tab. But, if that’s your pleasure, go for it, these options are calorie free too.

Want to add some flavor to your glass of water? In most sit-down restaurants and even some walk-up-and-order spots, you can request a slice of lemon. In many sit-down restaurants, particularly upscale ones serving alcoholic beverages, your options will be a slice of lemon, lime, or orange. Encourage kids to flavor their water with an orange slice or make their own lemonade with lemon wedges and sugar substitute.

Water with gas, fizz, or bubbles has also become plentiful. There are carbonated mineral waters (like seltzer, Perrier, San Pellegrino, or others) or club soda. They’re all calorie free and can satisfy that desire for carbonation. Yes, fizz! A slice of lemon or lime or a splash of fruit juice can jazz up these beverages. Note that tonic water, mainly available at bars, contains calories. However diet tonic water, while not generally available in restaurants, contains zero calories.

Milk

Most restaurants, from fast-food to upscale, stock one or more varieties of milk as a beverage choice, with whole milk being more common than fat-free milk. However, with the push to feed kids more healthfully and to increase healthier beverage options, fat-free milk is becoming easier to find. There may be some ethnic restaurants, such as those serving Asian fare, that don’t stock milk because it’s not a commonly used ingredient in their food.

Nearly everyone in America could benefit from drinking more fat-free milk for the calcium, vitamin D, and other nutrients. Children and adults in this country have a large deficit of calcium and vitamin D. Milk consumption has dramatically decreased over the last few decades, even for children. One key reason? People eat more meals out and, though it is more plentiful in restaurants today, milk is not the beverage of choice. When it comes to children, start young and teach them to select fat-free milk as a beverage option at most restaurant meals (see Chapter 6 for more on this topic).

Most restaurants offer whole or low-fat (2%) milk, with fat-free milk also gaining favor. Choose fat-free if it’s available or low-fat if that’s your best option. Fat-free milk rings in at 90 calories for 8 ounces, while whole milk has 150 calories for the same amount. The extra calories are nothing but unhealthy fat and cholesterol. Soy milk is also showing up more often today, but it is mainly available in coffee shops as a whitener.

Fruit Juice

Fruit juice—that is, 100% fruit juice—is available at some restaurants. You’ll find it at restaurants serving a full breakfast. Sit-down restaurants that have a full bar will have an array of fruit juices as well, such as orange, cranberry, and grapefruit, because they are used as mixers in alcoholic drinks. They’ll also be able to pour you a glass of tomato juice or Bloody Mary mix. Fast-food restaurants and coffee and bagel shops typically stock at least orange juice. More recently you see an onslaught of bottled drinks with fruit juice blends, fruit smoothies, mixes of tea and fruit juices, and more. This new wave of drinks provides a range of calories. Both fruit and vegetable juices are healthy vitamin- and mineral-dense beverage choices when served in reasonable serving sizes, such as 4–8 ounces. However, a 12-ounce bottle of fruit juice, the common serving available for purchase in a breakfast or sandwich shop, can load on 160 calories. That’s a lot when you want a serving of fruit, which is equivalent to 4 ounces. Bottled juice drinks have a Nutrition Facts label, so to know for sure, read it.

While pure fruit juice or vegetable juice is healthy and nutrient packed, you’re better off eating your fruit, rather than gulping it. Other than to treat hypoglycemia, that is. Whole fruit provides volume and fiber and the satisfaction of chewing.

Noncarbonated Sugar-Sweetened Drinks

It’s hard to keep up with all the noncarbonated beverages that want to convince you with their healthy looking labels that they’re nutritious. However, unless they are made with 100% fruit juice, they’re likely not. Many of these beverages—from fruit drinks and punch, to lemonade, energy drinks, and sports drinks—are available in restaurants, mainly coffee, bagel, and sandwich shops, in bottles that range in size from about 16–20 ounces. Sweetened lemonade and fruit punch is also available from fountain spigots in some fast-food and sandwich shops. These drinks are aimed at the taste buds of kids.

The FDA requires that fruit drinks not be called fruit juice if they contain less than 10% fruit juice (and most of them do contain less). Typically, these beverages, like soda, are sweetened with high fructose corn syrup and provide no redeeming nutrition benefits or nutrients. They’ve got a couple hundred calories of pure refined carbohydrate. You may find the diet counterparts to these fruit drinks and related beverages available at a few types of restaurants. Do make sure you turn the bottle or can around and stare at the nutrition facts, particularly the total carbohydrate count. Make sure that the nutrition facts listed are for the total container rather than for an 8-ounce serving. Look for a drink that contains zero or very few calories per serving. These are most often sweetened with one or more sugar substitutes. If you enjoy a fruit-flavored drink, try to make sure it’s a diet variety.

Coffee

Never before has such a big fuss been made over coffee. Nor has it ever been whipped into so many concoctions. Numerous chains from coast to coast make coffee drinks the centerpiece of their menu; baked items and ready-to-eat sandwiches are an afterthought in these restaurants. The national, actually international, leader in this field is Starbucks. The east coast has Dunkin’ Donuts and the west coast has Caribou Coffee. Plus, other local and regional coffee chains serve the beverages that people drink all day. Find information about coffee and coffee drinks served in restaurants in Chapter 11.

The debates about the health benefits of coffee in general, and caffeine in particular, continue with no absolute conclusions. Some large human studies that have prospectively observed the eating behaviors of adults and their ensuing health, note benefits of drinking coffee (caffeinated or decaf), such as a lower risk of type 2 diabetes. However, there is no conclusion about the health benefits or health risks of caffeine (a component in caffeinated coffee and tea). Some people can handle caffeine until midafternoon and others can drink a cup of java at night before going to sleep with absolutely no effect.

Whether you go for the kick of caffeine or drink it decaf, coffee starts off with essentially zero calories. That’s true whether it’s a regular brew or deep dark espresso. The calories creep in when scoops of sugar (16 calories per teaspoon) and half-and-half (40 calories per ounce/2 tablespoons) are stirred in. Even more calories tally up when you add in flavored syrups, whipped cream, and (oh, yes) caramel topping. Check out the nutrition totals for a sampling of these drinks in the Health Busters section of Chapter 11 and an even longer list of Healthier Bets.

It’s easy enough to lighten the calorie, carbohydrate, and fat gram load in coffee. And because the drinks are nearly always made to order, you can get your drink as you need it. Start with unadulterated coffee and avoid the sugary blends that some of the drinks are made from. Next, choose a low-fat whitener, such as low-fat or fat-free milk or soy milk. Do make sure the restaurant uses calcium-fortified soy milk if it is your regular coffee whitener.

Enjoy some flavorings if they are sugar-free or contain nearly zero calories, which some do. Skip the half-and-half, cream, and/or whipped cream. Hold off on the caramel topping or high-calorie blended-in ingredients. These add calories and saturated fat. If you need a touch of sweetness, use a sugar substitute (whichever suits your taste buds).

Espresso, a rich, dark, thick coffee, is served as a shot or two to finish off a meal or to sip with a sweet treat. Today, espresso is also the coffee used to make many of the coffee shop coffee drinks, from cappuccinos, to lattes or even iced coffee. Espresso has its roots in Italy. Some would define espresso as “power-packed coffee,” which explains why it is typically served in a demitasse (small cup, about 3 ounces) with a twist of lemon to run over the brim and sugar cubes to cut the biting, bitter taste. Espresso, before anything is added, contains no calories, fat, or cholesterol. It can be a satisfying tasty treat to finish off a meal in an upscale or Middle Eastern restaurant.

Tea

The options for tea are wider than ever. Even though tea is one of the most widely consumed beverages in the world, over the years it has mainly been consumed as a hot beverage. Yes, that’s changed! Today, many types of tea—from green, black, and oolong to blends of tea like chai, from herbal teas, to fruit and tea blends (with flavors like lemonade, pomegranate, or raspberry)—are now available. Plus tea is available hot or iced and by the cup or in a bottle. Find more about the tea-based beverages served in restaurants in Chapter 11.

The debate about the health benefits of tea continues, much like the debate on coffee but not as robust. Since teas (besides herbal or decaffeinated teas) contain caffeine, tea becomes part of the caffeine discussion noted above under coffee. However, cup for cup, tea most often contains less caffeine than coffee unless you drink it very concentrated. Generally speaking, it’s a healthy beverage if you just consume the tea and not the extras, like fruit, milk, and calorie-containing sweeteners that up the calories. Some evidence, though not conclusive, touts the presence of some disease-preventing antioxidants and phytochemicals in various teas.

In coffee and bagel shops as well as upscale restaurants serving fusion or ethnic fare, you usually have your pick of 6–10 varieties of common tea blends. A few regulars with caffeine are available decaffeinated as well, such as Earl Grey, English Breakfast, and Darjeeling. Then there are usually a couple of decaffeinated herbal teas available, such as chamomile, lemon lift, raspberry zinger, or orange and spice. When going upscale, you often get to choose your tea from a wooden box.

Don’t forget chai, which has become popular thanks to the large coffee chains. “Chai” is the word for tea in many areas of the world, including Asia. Chai tea is traditionally made from rich black tea, heavy milk, a combination of various spices, and a calorie-containing sweetener. The current versions of chai tea mimic the traditional and typically contain a hefty hunk of calories.

Then there are many versions of tea mixed with fruit juice or lemonade, like you’ll see at Starbucks and other coffee shops served in large plastic cups. You’ll find these at bagel and sandwich shops, too. Both types have typically been mixed up with some variety of fruit or fruit juice and calorie-containing sweeteners. Do beware of their healthy-sounding names. When going to purchase one of these drinks, read the label on the bottle or search out the nutrition facts so you know exactly what you’ll be sipping.

By all means continue to drink calorie-free hot or iced tea. If you want to keep these drinks calorie free, don’t adulterate them with calorie-containing sweeteners, fruit juice, or whiteners. If you do whiten and/or sweeten your tea, follow the same recommendations provided for coffee. Check the nutrition info for a sampling of tea drinks in the Healthier Bets section of Chapter 11.

Soda/Carbonated Soft Drinks

Soda, soft drink, or pop—the name depends on where in the country you live—is the beverage people drink most frequently with restaurant foods, particularly at walk-up-and-order restaurants. These restaurants like to sell you the largest portion possible because the profit margin is high and gets higher the larger the volume of soda sold. Today, sugar-sweetened soda is typically sweetened with a calorie-containing sweetener called high fructose corn syrup (learn more about HFCS earlier in this chapter). Skip sugar-sweetened soda as much as humanly possible, unless it’s all you’ve got to treat hypoglycemia. Aside from its thirst-quenching properties, soda is simply calories with no nutrition. A 20-ounce bottle of soda contains around 250 calories!

Where there’s regular soda, there’s usually also diet available, whether from the fountain, cans, or bottles. If you’ve just got to have your fizz, by all means go for the diet option with zip calories. There’s nothing nutritionally redeeming about diet soda, but you’ll at least be in the zero column for calories. If a sparkling water or club soda with no calories is available, have at it. It’s likely an even healthier choice—it’s just water.

Smoothies

As more people look for quick-to-guzzle meals and snacks, more restaurants are whipping up smoothies by the blender full. These frothy drinks can be made from a mixture of healthy ingredients, such as low-fat milk or yogurt and pieces of real fruit. However, they’re more commonly blends of some healthy ingredients with fruit-flavored syrups or concentrates. They’re also generally served in LARGE portions. So, whether they’re made with healthy ingredients or not, they usually tip the calorie scale on the high side. Most of the calories in smoothies are from refined carbohydrate with zero fiber. Got to have a smoothie? Find a restaurant that makes them with milk or yogurt and fresh fruit. Then share a small serving with at least one or, better yet, two dining partners. Treat a portion of a smoothie as a sweet treat or snack rather than using it as a meal replacement. Find more on smoothies in Chapter 11. And see Table 9.2 for nutrition information for nonalcoholic beverages commonly available in restaurants.

Alcoholic Beverages: Challenges and Choices

Restaurant meals are a common time to consume alcoholic beverages. This is particularly true at sit-down restaurants, especially at upscale dining spots. People newly diagnosed with diabetes who enjoy alcohol commonly ask these questions:

• Can I continue to enjoy alcoholic beverages?

• Which alcoholic beverages are best for people with diabetes?

• How can I fit alcoholic beverages into my eating plan?

• What are the guidelines for staying safe when drinking alcohol?

You’ll find answers to these questions in this book. In this chapter you’ll find a discussion about the general and diabetes-specific perks and pitfalls of alcohol intake plus information on how much is safe and healthy to drink. More specific details and tips on how to balance alcoholic beverages, glucose, and restaurant meals are in Chapter 5.

For personalized answers about how much and what types of alcoholic beverages are healthy and safe for you to drink, talk directly with your health-care providers.

How Much Alcohol Is Just Enough

The recommendations for alcohol for the general public (from the Dietary Guidelines for Americans) and for people with diabetes (from the American Diabetes Association) are the same: no more than a “moderate” amount of alcohol in a single day. “Moderate” is defined as one drink or serving of alcohol (defined below) for women and two drinks/servings for men a day, and this is the maximum amount people should consume in a single day (not an average over a few days at a time). The guidelines encourage refraining from binge drinking, which is defined in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans as consuming four or more drinks for women and five or more drinks for men within a 2-hour period. Binge drinking is a particular risk for people with diabetes who take blood glucose–lowering medications that can cause hypoglycemia. To learn more read Chapter 5.

Last, but not least, though the recommendation to drink in moderation is a healthy behavior, neither American Diabetes Association nor the Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend you start to drink alcohol if you currently do not drink. There are many other actions you can take to help you get and stay healthy, such as eating healthier, not smoking, and being physically active.

People with a history of alcohol abuse, pregnant woman, people with some medical problems, such as liver disease, pancreatitis, advanced neuropathy (diabetes nerve disease), or severely elevated triglyceride levels, and people taking prescription or over-the-counter medications that can interact with alcohol, should not drink alcohol. Nursing mothers can consume alcohol on occasion, as long as they plan this around feeding times.

Does one type of alcohol provide more health benefits than another? For many years you’ve heard about the health attributes of red wine; however, research doesn’t seem to show that one type of alcohol conveys more health benefits than another. It’s simply the effect of drinking alcohol that is beneficial. So, drink the type or types of alcohol you enjoy in moderation.

Benefits and Pitfalls of Alcohol Consumption

Yes, there are health benefits of alcohol! But there are pitfalls, too.

Alcohol’s General Health Benefits

Studies show that light to moderate alcohol consumption over time can increase insulin sensitivity and decrease insulin resistance. This effect is at the center of alcohol’s beneficial impact on decreasing the risk of metabolic syndrome, prediabetes, and type 2 diabetes and conveying other circulatory benefits. Improved insulin sensitivity can lead to lower fasting glucose and lower risk of heart disease, strokes, death from all causes, and it can improve cognitive function (thinking). Moderate alcohol intake doesn’t seem to raise triglycerides (though alcohol is not recommended for people with very elevated triglyceride levels) and may minimally raise HDL (“good”) cholesterol. Pretty nice list of health benefits!

However, excess alcohol intake—upwards of three or four drinks a day—does quite the opposite, by increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes and circulatory problems. Once again, the message of moderation prevails.

Diabetes-Specific Benefits of Alcohol

Alcohol’s ability to increase insulin sensitivity offers a bit of help to people with prediabetes and those in the first few years of a type 2 diabetes diagnosis, when every little improvement in insulin sensitivity can lower fasting glucose levels. The positive impact of alcohol on heart disease and blood pressure—and the circulatory system in general—is a plus due to the greater risk of people with type 2 diabetes having these conditions. Moderate alcohol consumption, regardless of the type of alcohol, seems to have minimal immediate (acute) or long-term effects on glucose control.

Alcohol’s Pitfalls

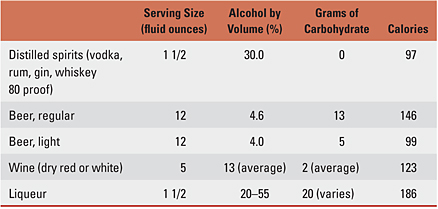

Yes, there are a few pitfalls to deal with as well. Alcohol contains calories (see Table 9.1) with next to no nutrition to speak of. However, studies show that people who drink in moderation don’t gain weight from alcohol. Heavy drinkers may. Calories from alcohol can add up quickly, as you see in Table 9.1. A couple of 12-ounce regular beers contain about 300 calories. If shedding weight is one of your goals, you’ll need to employ moderation. You simply can’t afford the calories of regular drinking. Plus it’s hard to fit nutrient-dense calories into your meal plan if alcohol is replacing them.

Adapted from American Diabetes Association Guide to Nutrition Therapy for Diabetes. 2nd ed. Franz MJ, Evert AB, Eds. Alexandria, VA, American Diabetes Association, 2012.

Safety is another concern with alcohol. Alcohol is enjoyable to many people due to its fairly rapid cerebral effect on the brain—it creates a loss of some inhibitions and helps some people relax and socialize. This is one reason it’s more common to drink alcohol when dining out and lingering over a meal or celebrating an occasion. But this effect on the brain can also impair judgment and physical and mental reactions, which raises concerns about drinking and driving. Bottom line: don’t drink and drive. For more specific details about how to manage consuming alcoholic beverages with restaurant meals, read Chapter 5.

Develop Your Alcoholic Beverage Plan

When you’d like to have a serving or two of alcohol, ask yourself these questions:

• When do you want to fit in an alcoholic beverage?

• Where do you want to consume it?

• What do you want to drink?

• How will you fit it into your eating and diabetes-control plan based on your priorities?

Maybe you decide to drink alcohol only when you dine out on the weekends or with one or two restaurants meals per week. Maybe at other restaurant meals you’ll drink nonalcoholic and noncaloric beverages. Or maybe you’ll drink alcohol only at home and not when you eat out. Maybe you’ll go for wine, beer, or a distilled beverage with no mixer. Or twice a week you’ll allot yourself a couple of glasses of wine before and during dinner and you’ll take a unit or two less insulin to compensate for the glucose-lowering effect of the alcohol. It’s up to you—but do figure out your alcoholic beverage game plan.

Tips to Limit Alcohol Intake

• Always have a noncaloric beverage by your side. Quench your thirst on this and slowly sip your alcoholic beverage to have it last longer.

• Need to have an nonalcoholic drink in hand that looks festive at a celebration? Order a club soda or diet tonic water with a splash of cranberry juice and a lime or lemon. Drinking alcohol too? Try alternating an alcoholic drink with a noncaloric, nonalcoholic one.

• Think about when you enjoy your one or two drinks the most during restaurant meals. Is it as you wait until the food arrives? As you enjoy your meal? To sip on as your meal concludes? As a sweet end to a meal (think a liqueur or dessert wine)? Order your alcoholic beverage when you enjoy it most. Don’t sip it down beforehand.

• Order alcohol in small quantities: wine by the glass rather than the bottle (unless you have enough people to share), beer by the can or 12-ounce glass rather than by the pint or pitcher.

Alcoholic Beverage Categories

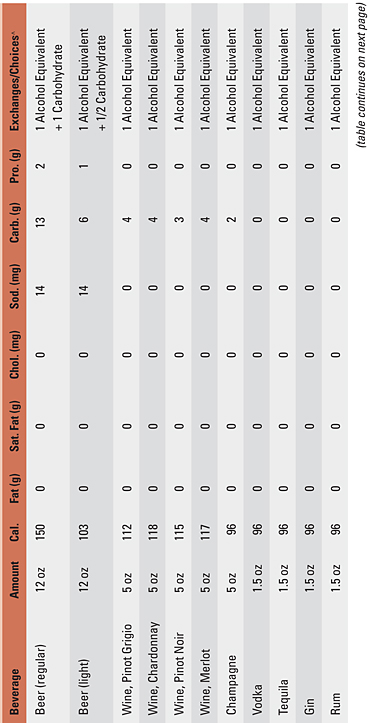

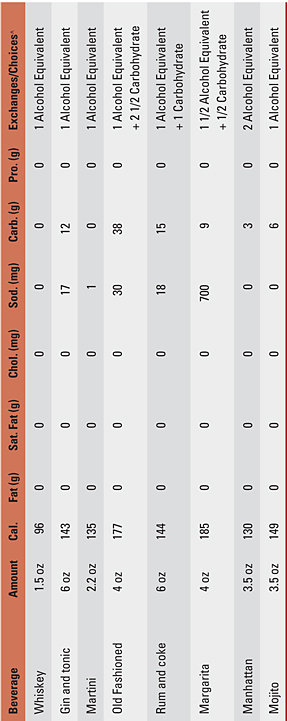

If a restaurant serves alcohol, the types they serve usually don’t differ much, other than variations in the types of wine, beer, and liqueurs they serve. Table 9.3 contains the calories and key nutrition information for common alcoholic beverages.

Beer

It might be labeled Singha in Thai restaurants, Dos Equis in Mexican dining spots, or Bud or Mick in a local American bar and grill. Beer is a brewed and fermented drink. Most beers are created by blending malted barley and other starches and flavoring them with hops. However, with microbreweries multiplying, new methods of brewing beer as well as new beer ingredients are being found. Though beer might be light, dark, or caramel in color and gutsy or mellow in taste, from a calorie stance, beer is beer. The calories can add up fast: 12 ounces of regular beer contain about 150 calories. Light beer (that is light in calories, not color) can cut calories down to about 100 calories for 12 ounces.

Wine

Whether it’s red, white, or rosé, domestic, French, or Italian, wine contains about 100 calories for 5 ounces. If you typically split a bottle of wine, you might want to reduce the quantity by ordering wine by the glass. Remember to order it at the time during the meal you most want it. One calorie-conscious strategy, if you enjoy it, is to order a wine spritzer with white, red, or rosé. But make sure the spritzer is made with noncaloric club soda rather than a clear sugar-sweetened soda. Ask the bartender to mix it half and half rather than the usual three-fourths wine and one-fourth soda.

Champagne

This beverage is classified as a wine and is named after its origins in Champagne, France. Champagne is slightly higher in calories than most wines, and the calories depend on its dryness. Drier champagne is slightly higher in calories. Champagne shows up at brunches in mimosas, where it is teamed with orange juice, or on its own as a celebratory drink to welcome a new couple into married life or to toast other life celebrations and accomplishments.

Distilled Beverages

Rum, gin, vodka, and whiskey are all classified as distilled spirits. Interestingly, like wine, they all contain about the same number of calories—about 100 calories per jigger (or 1 1/2 ounces) for 80-proof liquor. Many people have the misconception that rum, scotch, and other slightly sweeter distilled spirits are higher in calories. That’s not true. If hard liquor is what you prefer, enjoy it in moderation. Don’t get caught up in the misconception that wine and beer have many fewer calories than distilled liquor. You simply get more volume for your calories with wine and beer.

The problem with distilled spirits is that they are often mixed with other high-calorie nonalcoholic liquids, such as fruit juices, tonic water (regularly sweetened), milk or cream, syrups, or other high-calorie liqueurs. For example, a piña colada (5 ounces) has 250 calories and a Kahlua and cream (3 ounces) has 200 calories. It’s best to limit drinks that are combinations of distilled spirits, liqueurs, fruit juice, regular soda, tonic water, or cream unless you’ve got calories and grams of carbohydrate to spare. Order distilled spirits on the rocks with a splash of water, club soda, or diet soda.

Liqueur and Brandy

Another category of alcoholic beverages is liqueurs, cordials, and brandies. Liqueurs and cordials synonymously describe beverages such as the familiar Kahlua, Amaretto, Grand Marnier, Chambord, or one of the many brandies available. You sip these straight up or on the rocks as after-dinner drinks or in combination with other distilled spirits in a mixed drink. Brandy is created from distilled wine or the mash of fruit. The most familiar brandy is Cognac.

Liqueurs, cordials, and brandies ring in at about 185 calories per jigger (1 1/2 ounces). That’s a substantial number of calories for a small amount of liquid. A good way to enjoy liqueurs and get more ounces for your calories is to make liqueur part of a coffee drink, such as Irish coffee or Kahlua and coffee. By adding a shot of liqueur to black coffee, you increase the volume substantially. Ask the server to hold the whipped cream and sugar. One of these coffee drinks at the end of a meal may quench your sweet tooth. As others are downing their mega-calorie confections, you can sip your relatively low-calorie, no-fat dessert. Cheers! (See Table 9.3 for nutrition information for alcoholic beverages commonly available in restaurants.)

*Consider the nutrition information for these beverages as an estimate and not specific for the actual restaurant beverage you drink. Use specific information for the beverage served when it is available.

∧Calculated based on the information provided in American Diabetes Association and Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Choose Your Foods: Food Lists for Diabetes, 2014.