In this chapter, we’ll guide you through the process of assembling and organizing points for your argument and writing the essay. Then we’ll give you some practice.

Anyone can learn to write an essay. Yes, anyone. You need a plan to follow (which we’ll give you in this chapter) and confidence (which will increase as you get more practice writing and evaluating your own work).

You can use our method to help you analyze the arguments you encounter in everyday life beyond the test, too. Try it the next time you get a message from someone urging you to buy something or do something. Switch into active reading (or active listening) mode right away and start looking for the main arguments and how well they’re supported. You’ll soon know if you should consider the request or not.

From studying the prompt (the test writers call it “unpacking the prompt”), you know what you need to do:

1. Analyze the arguments in the two passages to decide which author you think provides stronger support.

2. Write your own argument about which one is better supported, using evidence from the passages.

3. Be objective; consider the support, not the topic.

4. Do it in 45 minutes.

First, we’ll define each author’s argument using our active reading skills. Remember active reading from Chapter 5? That’s where you summarize and ask questions as you read, forcing the passage to give you what you need from it. And that’s where you’ll start assembling the points and evidence for your argument.

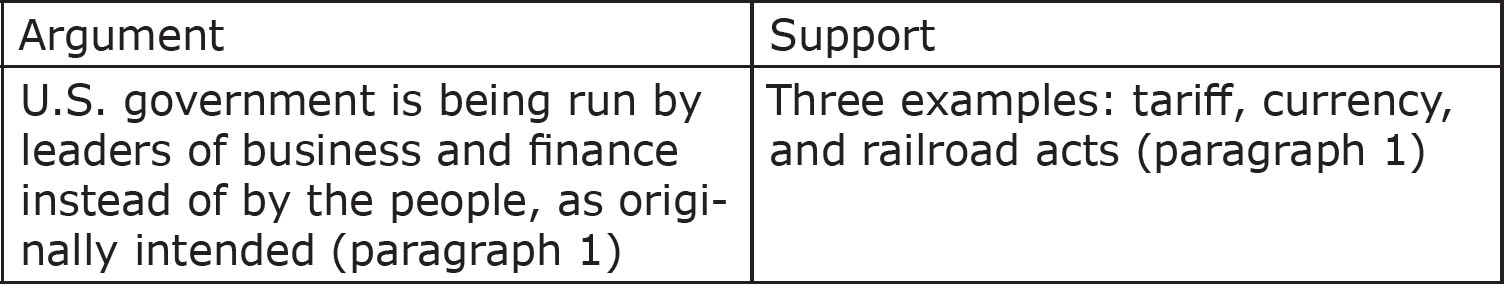

Let’s try active reading with a brief example. While you are reading the excerpt below (not after you’re done), determine the author’s argument and the support he provides for it, and note them briefly on your scratch paper. You’ll likely find it helpful to make a quick chart for yourself, such as this one:

Excerpt from The New Freedom, by Woodrow Wilson

For indeed, if you stop to think about it, nothing could be a greater departure from original Americanism, from faith in the ability of a confident, resourceful, and independent people, than the discouraging doctrine that somebody has got to provide prosperity for the rest of us. And yet that is exactly the doctrine on which the government of the United States has been conducted lately. Who have been consulted when important measures of government, like tariff acts, and currency acts, and railroad acts, were under consideration? The people whom the tariff chiefly affects, the people for whom the currency is supposed to exist, the people who pay the duties and ride on the railroads? Oh, no! What do they know about such matters! The gentlemen whose ideas have been sought are the big manufacturers, the bankers, and the heads of the great railroad combinations. The masters of the government of the United States are the combined capitalists and manufacturers of the United States.

That was published in 1913 so yes, the sentences are a bit long, but we can still define the author’s main points. Your chart might look like the one below:

On the test, of course, you’ll be working with several paragraphs in each passage, so you would also note the number of the paragraph that contains each point so you can find it again quickly. And since you’re under a strict time limit, your chart would contain short forms and abbreviations that are meaningful to you. You should note all three of the types of support outlined in Chapter 10, too: evidence, reasoning, and assumptions. (See this page.)

Apply the Strategy

Use active reading and scratch paper (or your note boards on test day) to boil the passage down to the evidence you need for your essay.

What’s the value of this chart? It boils an article, or a news release, or a letter—any of the different types of documents you might encounter in a passage—down to one common bare-bones list of the arguments and support points you need for your essay. It saves you the time of rereading and flipping from page to page just to find something again. And it gives you a clear picture of the support in each passage, making it easier to decide which one you think provides the best. That’s the topic of your essay, after all.

Later on in this chapter, we’ll give you some examples that will let you practice active reading and boiling the passages down into argument/support charts.

You’ve read both passages actively, and now you’ve got a couple of quick charts listing the authors’ arguments and the support for those arguments. You can make a clear case for which author provides better support for his or her position. In other words, you have the main points that you want your essay to hit. Now what?

Let’s work through an example of how you would organize and develop your essay. Suppose one of the two passages on the test is a letter to the editor from a local consumers’ group complaining about the large, unexplained car insurance rate increase imposed on drivers in that city. The other is a response from a local association of insurance brokers arguing that, after three years of flat rates, an increase was overdue.

First, let’s look at the template—or framework—for the essay. We’ll discuss the pieces in more detail later, but first we need a picture of what the whole structure looks like.

The Beginning

Introductory paragraph

Attention-getter

Thesis statement

Big picture list of evidence that proves the thesis statement

The Middle

One paragraph for each piece of evidence that proves the thesis statement

Topic sentence

Evidence from the passages

Explanation of how the evidence supports the thesis statement

The End

Restatement of the thesis in different words

Reminder of the pieces of evidence that prove the thesis

In 45 minutes, you won’t be able to produce a polished essay. Even the test writers regard this as an “on-demand draft” and expect that it will contain some errors. However, if you have a concept of how an ideal essay would be structured, you’ll have a plan for where to start and what to write in the limited time available.

The essay has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Well of course, you may say. However, it isn’t quite as simple as it sounds. The essay has a specific beginning, middle, and end. You might be familiar with the classic advice given to people who have to make a speech: “Tell them what you’re going to tell them, tell them, tell them what you told them.” That’s a pretty good outline of the beginning, middle, and end of the essay, too.

This is the first paragraph, which sets expectations about what readers will find in the rest of the essay. It has three components.

The Attention-Getter Ideally, the first paragraph begins with an attention-getter—something that would make a human reader want to see what’s in the rest of your essay. Although you don’t have a human reader for the GED® Extended Response, an attention-getter will still get your essay off to a strong start for the robo-reader. Remember, everything it knows, it learned from human graders.

What would capture a reader’s attention?

You could begin with a question—for example, “Why have car insurance rates gone up so much?”

You could start with what’s called the “startling fact”—for instance, “The average U.S. driver pays about $900 in car insurance premiums.” (You can probably find a good startling fact candidate in the two Extended Response passages.)

You could open with a quotation (if one pops into your head without spending time thinking of one). It doesn’t have to be a direct quote, using the exact words of whoever said it. You could paraphrase it instead. For example, a paraphrase such as “Abraham Lincoln claimed that it was impossible to fool everyone all of the time” would avoid trying to remember Lincoln’s exact words. In this example, you’d need to add a sentence tying that quote to the passages: “However, in its letter to the editor, the consumers’ group complains that car insurers seem to be trying to do just that—fool all of their customers into accepting unexplained rate hikes.”

The essay begins with a three-part paragraph.

An attention-getter, which makes the reader want to keep going

A thesis statement, which outlines what the essay will prove

A big picture outline of the arguments that prove the thesis statement

If you can’t think of an attention-getter quickly, then you could simply begin with a statement about the two passages: “Rising car insurance premiums are drawing complaints from consumers and forcing the industry to defend itself, as these two passages reveal.” This leads readers into the essay rather than hitting them over the head right at the start, and it’s a much stronger opening than “This essay will discuss…” or “The subject of this essay is….”

You’re not writing about car insurance premiums, though; you’re writing about which side (consumers or brokers) makes the stronger case in the passages. The thesis statement, which we’ll discuss next, makes the topic of your essay clear.

The Thesis Statement After the attention-getter comes the thesis statement, which makes the claim that you intend to prove in the rest of your essay. In this case, the claim is that passage X provides the stronger support for its position. The thesis statement might read as follows:

“In the dispute between drivers and insurance brokers, the consumers’ group provides stronger evidence for its position that the steep rise in car insurance premiums is both unfair and unnecessary.”

Depending on your attention-getter, you might need to add some type of transition sentence to tie that first sentence to the thesis statement.

Although it’s called a statement, the thesis can be more than one sentence long. It should be specific: The example above mentions the two sides, the subject of the dispute, and the stronger side’s position. It should also cover only what you will support with evidence in your essay.

The Big Picture Arguments Finally, the first paragraph ends with a high-level list of the evidence that supports your thesis statement and which you’ll explain in detail in the middle paragraphs. You’ve already got a list of this evidence (the authors’ arguments in the chart you made up during your active reading of the passages). Sticking with the car insurance topic, let’s say you found three pieces of evidence that make the “stronger” side’s support better. You would finish the introductory paragraph by listing those three arguments:

“As the consumers’ group points out, insurance companies made record profits last year, while the average driver had to cope with a 10 percent increase in gas prices but only a one percent rise in wages.”

In the next few paragraphs (likely the same number as the number of points you outlined in the “big picture arguments” part of the first paragraph), you’ll provide evidence to support each argument that proves your thesis. Be sure to explain why or how it proves your thesis. Remember, too, that you need to incorporate some evidence from the less-supported passage, too. Deal with one point per paragraph, and start each paragraph with a topic sentence.

The Topic Sentence The topic sentence is just what it says—a sentence that introduces the topic of the paragraph. Like transition and signal words (see this page in Chapter 5), it guides the reader through your essay and demonstrates your skill in organizing and developing your argument, traits on which you’ll be graded. It does not give details about the topic (such as dollar amounts or dates or specific examples). Those come later in the paragraph.

Let’s take the example of the consumers’ first argument in the car insurance case. They say that car insurance companies already made record profits last year. Read the paragraph below and see how you think it flows, not counting the bracketed words, which are just our own notes and would not be in the actual essay. Remember that it would be the next paragraph after the introductory paragraph.

The consumers’ argument that the car insurance industry recorded $10 billion in profits last year, more than any year in the past decade, proves that the insurance companies don’t really need extra money. The brokers’ position [here we’re drawing in some evidence from the less-supported passage, too] is much weaker because it doesn’t address the industry’s financial success. Three years of flat premiums do not justify raising prices, as the brokers argue, when the insurance companies have already made so much money.

The essay writer just jumped into that first argument. Now see how much more smoothly this writer glides into the argument by using a topic sentence before getting into specific details such as $10 billion in profits.

The consumer group refutes the brokers’ claim about cash-poor insurance companies. The consumers’ argument that the car insurance industry recorded $10 billion in profits last year….

The next paragraph (the third one), could then begin with a topic sentence introducing the consumers’ second argument and making a smooth transition to the new point.

On the other hand [this signals a transition], the consumers argue, they are already paying more to drive.

Following that topic sentence, you would provide details about this second argument (the 10 percent increase in gas prices), and point out what makes it stronger (likely the brokers ignored the issue).

The fourth paragraph would repeat this formula with the third argument, which says consumers’ wages haven’t increased enough to cover the extra driving costs they already face.

The Evidence The rest of each middle paragraph will give details about the “relevant and specific” (as the prompt says) piece of evidence you’re explaining in that particular paragraph. Again, this information is in the chart you made during the active reading phase. So, continuing on from the topic sentence, you’ll

describe the author’s argument and the support he or she provides for that argument in the passage; remember to be specific

explain why that evidence proves your thesis that one passage has the better support (in other words, explain why it’s relevant)

Be specific. If the passage says the price of cabbages fell by two percent, use that product and figure. Don’t be vague and say the price of vegetables is lower.

Here’s the complete paragraph describing the consumer group’s first argument, with notes pointing out what function each part of the paragraph performs.

The consumer group refutes the brokers’ claim about cash-poor insurance companies [the topic sentence]. The consumers’ argument that the car insurance industry recorded $10 billion in profits last year, more than any year in the past decade, [the argument and support for it] proves that the insurance companies don’t really need extra money [how this argument proves the thesis that the consumers’ case has better support]. The brokers’ position is much weaker because it doesn’t address the industry’s financial success [evidence brought in from the other passage]. Three years of flat premiums do not justify raising prices, as the brokers argue, when the insurance companies have already made so much money [how this argument is weaker, which again proves the thesis that the consumers’ case has better support].

Quoting and Paraphrasing Evidence How you incorporate evidence into your essay is important. You can’t quote directly from the passage unless you put the author’s words in quotation marks. Without the quotation marks, it’s called plagiarism. In many colleges, that earns you a black mark on your record the first time and expulsion the second. Adults well into their careers have lost their jobs when plagiarism from decades earlier was exposed. So it’s a good idea to get into the habit of avoiding plagiarism.

How do you include evidence from the passages, then? Most of the time, the answer is paraphrase—rephrase the evidence in your own words. For example, let’s say the brokers’ passage contains the following argument and support for the argument:

Insurance companies report little or no increase in average premiums during the past three years. However, claims payouts have risen, on average, by three percent in each of those years.

Try rephrasing that in your own words.

Did you end up with something like “The brokers argue that premium revenue has remained flat for three years, while claims expenses have kept increasing”?

Next, you need to explain why that paraphrased piece of evidence is important to your thesis.

The brokers weaken their own case by mentioning rising claims costs but failing to acknowledge the other side of the story: the record profits that more than cover the insurance companies’ higher claims payouts.

When should you use a direct quote (in quotation marks)?

When the passage author’s exact words are important for proving your thesis

When the author phrases an idea in such a unique way that a paraphrase wouldn’t convey its true meaning accurately

Both cases will be rare in the passages you’re likely to encounter in the Extended Response section, so you should usually count on paraphrasing your evidence. You would also be sure to mention which side of the debate offered the evidence you’re using.

Paraphrasing Exercise Imagine the following statements are made in a passage. Try paraphrasing them so you can use them as evidence in your essay. Some possible paraphrases are below the list of statements.

1. A landmark study conducted in Antarctica found that penguins were thriving despite the evidence of the toll taken by climate change on other facets of the environment.

2. In its report, the commission concluded, “We should all learn from the experiences of First Nations people, who are trying to strike a balance between their traditional customs and the change demanded by industrial development.”

3. Although fish farming increases the supply of fish, there is alarming evidence that it lowers the quality.

There is no one “correct” paraphrase. An acceptable paraphrase should be in your own words and should convey the content of the original statement accurately. Below are some possible ways to paraphrase these statements.

1. Penguins in Antarctica are flourishing, according to a pioneering study, even though climate change is causing environmental damage elsewhere on the continent.

2. The commission’s report highlighted the lessons to be learned from the conflict between the growth of new industries and the traditional way of life for First Nations.

3. Evidence suggests that fish farms lead to higher production but lower quality.

Ideally, the final paragraph concludes your argument by restating your thesis in different words, and reminding readers of the arguments that prove your thesis. Your final paragraph will be stronger if you simply say it and avoid starting with “In conclusion,…”

Because it considers both consumers and the insurance industry, and backs up its claims with actual figures, the consumer group’s letter to the editor provides the better support. (This topic sentence introduces the main arguments and restates the thesis.) The group draws a strong contrast between the industry’s record profits on the one hand and, on the other, a 10 percent increase in drivers’ fuel costs that must be financed with only a one percent average increase in wages. The brokers’ weak argument that a premium increase is overdue, and their failure to consider consumers’ financial hardship, make their position the weaker of the two. (These sentences remind readers of the main arguments in the passages.)

This is the classic template. You might even remember it from earlier years in school. The first paragraph is the introduction (the beginning described above). Along with the attention-getter and the thesis statement, it gives three high-level reasons why the thesis statement is true.

Each of the next three paragraphs provides details about one of those three reasons. The second paragraph begins with a topic sentence covering the first reason you mentioned, and explains details about it. The third paragraph does the same for the second reason, and the fourth paragraph for the third reason. Those paragraphs are the middle described above.

The fifth paragraph is the conclusion (the end). It wraps up the thesis statement and the details from the middle section, and concludes your argument neatly. It doesn’t simply restate the introduction, though, because by now you’ve added details that put meat on the bare bones of the introduction.

Of course, your essay doesn’t have to be five paragraphs. You might have four reasons for your thesis statement, or only two. There might be six reasons, but two of them are so weak they’re not worth discussing. There is an expectation that the essay will be more than one paragraph, but that’s the only guideline the test writers give. The essay can be as long or as short as the time and doing a good job of the prompt task allow.

There is no set length or number of paragraphs for your essay.

The template above gives you an organizational structure into which you can pour your essay (remember, organization is one of the traits on which you’ll be graded) and a plan to follow in developing your argument about which passage has stronger support.

You’ll save time and write a better essay if you spend five minutes planning.

The template also explains why you don’t just jump in and start writing. Your essay will sound like you just jumped in and started writing. For a coherent, persuasive essay that responds to the prompt, “hangs together” well, and gets a high score, you first need to plan it. That’s where prewriting comes in.

Understanding your task through upfront thinking and planning has a tremendous impact on the quality of the final product (your Extended Response, in this case). As one of the world’s great minds said,

“If I had an hour to solve a problem I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.”

—Albert Einstein

We’re certainly not advocating that you spend more than 90 percent of the time thinking about the task in the prompt, but do spend five minutes or so thinking about why one passage provides stronger support, and planning the order in which you’ll discuss the evidence from the passages. Use a note board to jot down any ideas you have for a strong opening paragraph and conclusion. Write a number beside each point in your argument/support chart to remind yourself which claim you want to cover first, second, and so on. You can cross off each one as you finish discussing it, so you’ll see the progress you’re making.

Taking a few of your 45 minutes to plan will save you from getting 40 minutes into writing and realizing you’re badly off track. It will also leave you a couple of minutes at the end to review your essay so you can improve it and fix errors. (There are no spelling or grammar checkers for the Extended Response section, so you’re on your own.)

Your goal with prewriting is to have the whole essay essentially done—in your head, in thin air, on your note boards, wherever. It’s just not written down yet, and that’s all you need to do with the next 30 or so minutes, leaving yourself a couple of minutes at the end to review and improve what you’ve written.

You already encountered several ways to improve your writing: the eight areas of language use targeted on the GED® test (see this page in Chapter 8) and the use of a topic sentence to begin each paragraph (see this page in this chapter).

Here are two more tips to make your writing stronger, more interesting, and easier to read.

5 minutes—Actively reading the two passages, noting the main arguments and supporting points on the chart

5 minutes—Prewriting

32 minutes—Writing

3 minutes—Reviewing and improving the essay

45 minutes

As the name implies, with an active verb, the subject is performing the action. With a passive verb, the subject is passive; the action is being done to it. Take a look at these stripped-down examples:

John closed the door. (That’s an active verb. The subject, John, is doing the closing.)

The door was closed by John. (That’s passive. The subject, the door, is getting the action done to it.)

Recognizing active and passive verbs gets a bit more complicated when phrases and clauses enter the picture:

Tired, cold, and hungry from their frightening adventure in the dark woods, the three boys began devising a plan to return home without attracting the attention of anyone in the house. (That’s active—the wayward boys are devising the plan.)

Although the antique mahogany piano weighed a ton and would have sold for a fortune, it was unloaded from the moving van quickly and carelessly, in complete defiance of its great value. (Here’s a passive verb—the subject, the piano, is getting the action of being unloaded done to it.)

There are a few cases in which you might want to use a passive verb. Let’s say the owner of the small company where you work forgot to pay the computer service contract fee last month, leading the service company to cancel its contract. What do you tell Sofia in accounting when she asks why she can’t get her computer fixed? Do you say, “Our idiot boss forgot to pay the computer service invoice last month”? (That’s an active verb, by the way—the subject is doing the forgetting.) No, not likely. You might say something like, “The bill wasn’t paid on time last month.” That’s passive—the subject is the one getting acted upon (in this case, not being paid). By using a passive verb, you can focus on the action and avoid blaming the one who carried out that action (the boss).

Cases in which a passive verb is a better choice are rare, though. Your writing will be stronger and more interesting to read if you use active verbs most of the time.

Try turning the passive verbs in the following sentences into active verbs. You’ll find answers below. After you’ve finished, compare the active and passive versions. Notice how much stronger and easier to read the active version is.

1. An umbrella was purchased by Juanita because of the weather forecast for several days of rain.

2. Since it was clearly dying, the tree was felled by city maintenance workers.

3. After receiving a prize for the best children’s book of the year, the author was honored at a lavish reception given by the local literary society.

4. The house was renovated during the winter by electricians, plumbers, and painters.

Here are some possible answers:

1. Juanita bought an umbrella because the weather forecast called for several days of rain.

2. City maintenance workers felled the tree because it was clearly dying.

3. The local literary society held a lavish reception to honor the author of the best children’s book of the year.

4. Electricians, plumbers, and painters renovated the house during the winter.

How many paragraphs like the one below could you read?

Carrots are a root vegetable. Carrots are healthy. Carrots contain beta-carotene. Beta-carotene is an antioxidant. Carrots have Vitamin A. Vitamin A is good for vision.

Are you tired of those short, choppy sentences yet? They’re all the same structure and all about the same length. They soon become boring, and they make the topic they’re describing sound boring, too.

Look what happens when you combine these short sentences in different ways, though. Now the subject is interesting and the writing is more engaging.

Carrots, a root vegetable, are healthy because they contain the antioxidant beta-carotene. They also have Vitamin A, which is good for vision.

Carrots are loaded with beta-carotene, an antioxidant. This root vegetable is also healthy because it contains Vitamin A, a vision-boosting nutrient.

Carrots, a member of the root vegetable family, provide the vision and health benefits of Vitamin A and the antioxidant beta-carotene.

Health and vision benefits come from carrots, a root vegetable, because of the beta-carotene (an antioxidant) and Vitamin A they provide.

As those examples show, you can combine short sentences into more interesting structures in several ways.

By coordinating or subordinating thoughts from two or more sentences (see this page in Chapter 8)

By using phrases (“Carrots, a member of the root vegetable family,…”)

By using a series of words (“…beta-carotene and Vitamin A”)

By using compound subjects or verbs (“Health and vision benefits come from carrots…”)

Try your hand at combining the following short sentences into more varied structures. See how many different solutions you can create. One possible answer is below the short sentences.

The house was painted white. The house was old. The paint was faded. The stairs were crooked. The porch floor had a hole. Some windows were broken. The house was empty. The house was not welcoming.

There are many possible ways to combine those sentences into a more interesting description of the house. Here’s just one way:

The old house, with its faded white paint and broken windows, stood empty. Its crooked stairs and unsafe porch floor made it seem unwelcoming.

Because you planned your essay before you started writing, you should have about three minutes left to review it. The test writers don’t expect a perfect job in 45 minutes (they probably couldn’t do a perfect job in 45 minutes, either). However, you should use the extra time to improve your essay as much as you can, revising and editing it as you read through it.

When you revise your work, you’re making changes to the content. No, you won’t have much time to do this, but you can check to make sure that you’ve supported each of your arguments with evidence drawn from the passages, and that you’ve explained how the evidence proves your thesis (that one passage is better supported than the other). If you notice a statement that seems unclear, see if there’s a better way to say what you intended.

Editing involves simply correcting language and spelling errors, without changing the content of your essay. Watch for the eight language use points explained in Chapter 8. (See this page.) Remember, too, that you can’t rely on spelling or grammar checkers in the test.

The test has no spelling or grammar checkers.

Let’s use a fairly straightforward example to work through the process of building and organizing an argument. The first passage is a flyer for a seminar at which modern urban cave dwellers can learn about the Paleo diet, the diet of the hunter-gatherers who roamed the earth before the birth of agriculture and the domestication of livestock. The second is a warning notice on the bulletin board of a sports medicine clinic that has many patients who do CrossFit training, a program that recommends the Paleo diet.

The summary (in the top right-hand corner of the screen) would read as follows:

While the seminar flyer promotes the benefits of the Paleo diet, the sports medicine clinic warns about its dangers.

The prompt (below the summary) would read as follows:

In your response, analyze both the flyer and the clinic’s warning to determine which position is better supported. Use relevant and specific evidence from both sources to support your argument.

Type your response in the box below. This task may require approximately 45 minutes to complete.

The passages will appear on the left side of the screen, spread across several pages, which are numbered in the tabs across the top.

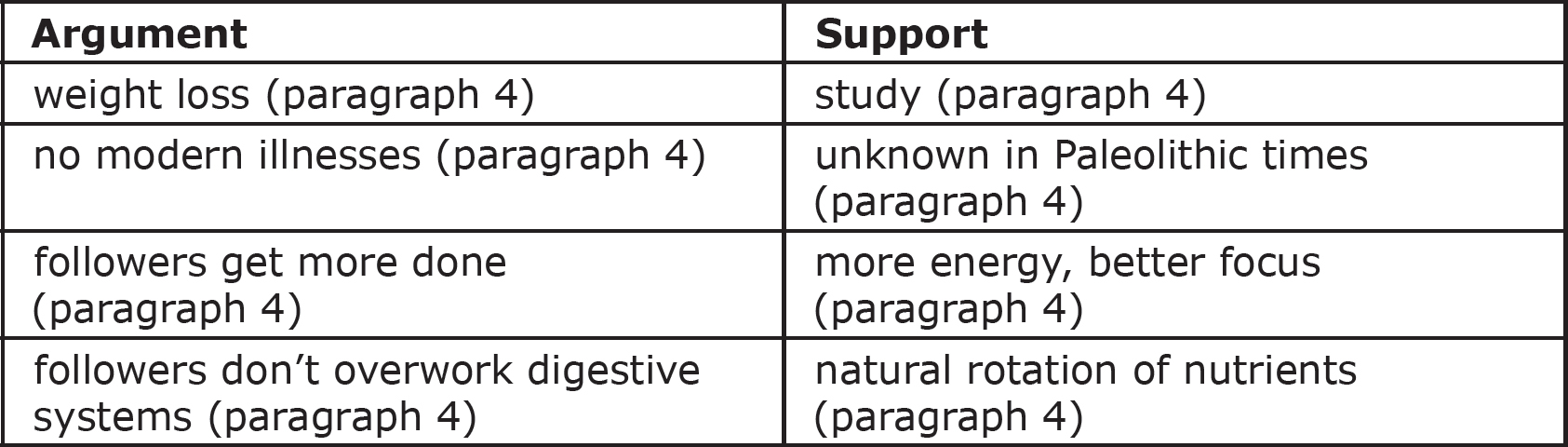

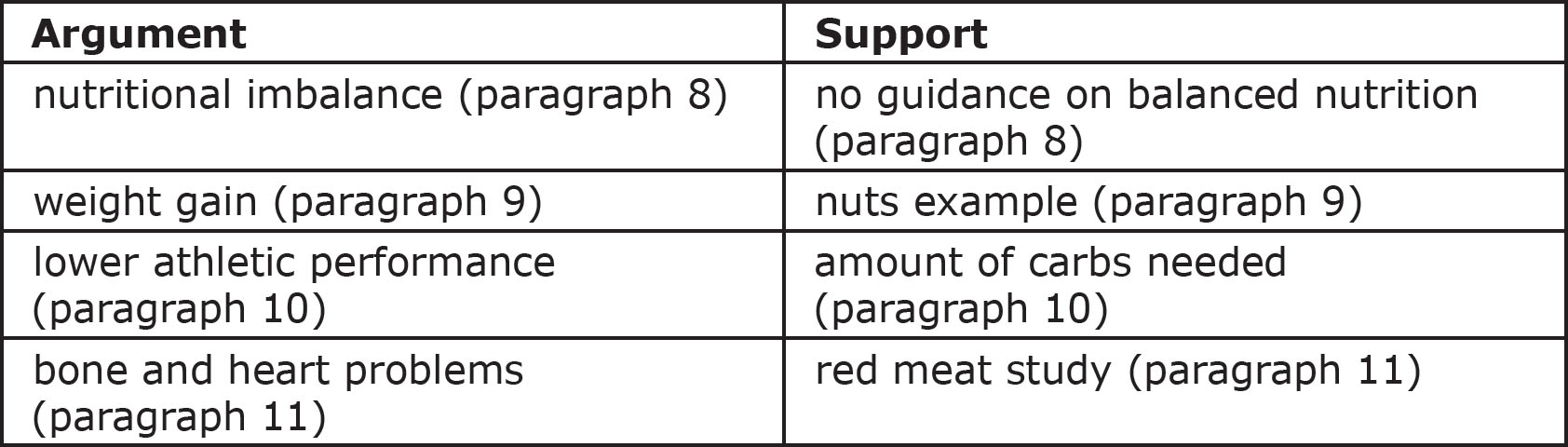

Use active reading to extract the authors’ arguments and support as you read, and note them in the chart. Then plan, write, and review your essay. Use the questions listed in Chapter 10 (see this page) to assess your own work. Then read the suggestions at the end of this example.

Passage A

Are you living in an unheated, unlit basement cave but still eating like it’s the 21st century?

1 Embrace the Paleo diet and harmonize your lifestyle!

What is the Paleo diet?

2 It’s a way of eating that’s close to that of primitive humans. It means eating the foods that our bodies evolved to consume.

3 The Paleo diet eliminates all foods that were not available in Paleolithic times. It avoids many staples of the modern American diet, such as grains, dairy, high-fat meats, starchy vegetables, legumes, sugars, salty foods, and processed foods. It includes foods that are as similar as possible to foods available to Paleolithic man. That means grass-fed beef and free-range bison instead of the corn-fed meat readily available at most grocery stores.

What makes it good for you?

4 • By eliminating legumes, grains, and processed foods, the Paleo diet results in a healthy weight loss for most people. In a study of 14 participants, those who followed a strict Paleo diet lost an average of five pounds after three weeks on the program.

• Debilitating diseases such as cancer, arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and diabetes are a modern problem, brought on partly by cultivated crops. These illnesses were unknown in Paleolithic times, when people ate a diet rich in meat and in the berries, fruits, and nuts that grew naturally around them.

• The Paleo diet is “clean.” It doesn’t contain additives, preservatives, or chemicals that have been linked to lower energy levels and problems focusing on detailed tasks. The plant nutrients in the Paleo diet have significant anti-inflammatory benefits, and the higher red meat intake leads to an increase in iron. Followers find they can accomplish more in their day.

• The Paleo diet promotes a natural rotation of nutrients in harmony with the seasons and the landscape. By eating only what would have been available in a particular season and location, people following the Paleo diet avoid overworking their digestive systems with out-of-synch foods, such as fresh oranges in the depths of the Wisconsin winter.

Want to learn more?

5 Join us for a free seminar to

• see the Paleo diet creator, Dr. Loren Cordain, on video as he explains the theory and benefits of eating the Paleolithic way

• hear real-life stories from fans who will never go back to a modern diet

• sample some Paleo staples

Tuesday night at 7:30 p.m.

Charming Gulf District School auditorium at the corner of Relling & 184th St

Don’t just live like our ancestors—eat like them too!

Passage B

6 The medical staff at Sutton Sports Medical Centre cautions patients about the harmful effects of the Paleo diet, which many of you are following.

7 The potential risks include:

8 Nutritional imbalance—Even with a very long list of allowed foods, the Paleo diet does not provide guidance on a balanced approach to nutrition. It also does not guarantee that people following the plan get enough of certain nutrients that are necessary to optimal health.

9 Weight gain—Because many of the allowed foods (such as nuts) are very high in calories, some people may find that following the Paleo diet actually causes weight gain instead of the rapid weight loss promised by the program. For instance, calorie consumption becomes a problem if a person eats five pounds of nuts in the course of one day.

10 Suboptimal athletic performance—The diet is restrictive in carbohydrates, which may be inadequate for athletes who use carbohydrates as a source of energy when exercising. Athletes need between three to six grams of carbs per pound of body weight per day; this is very difficult to achieve when consuming only the foods allowed by the Paleo diet. Thus, athletes may be faced with suboptimal performance.

11 Bone and heart problems—Removing all dairy products from your diet can cause a significant decrease in calcium and Vitamin D. A reduction in these essential nutrients can be harmful to bone health. In addition, the diet’s focus on red meat can cause heart problems; a 2012 study confirmed that red meat consumption is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

12 The clinic’s resident nutritionist, Dr. Arpad Geuin, is available to create a diet plan customized to your nutritional needs and athletic goals.

Here’s How to Crack It

Follow the steps we’ve explained.

1. Build your argument, using active reading to extract evidence (the authors’ arguments and how they support those arguments), and note them on the chart.

2. Decide on your thesis (which passage is best supported).

3. Plan how you will organize the evidence.

4. Fill in the essay template to write your essay.

5. Review and improve your work.

This example makes it easy to find the arguments each side uses to make its case. In most of the passages you’ll encounter in the Extended Response section, the arguments will be “buried” in text paragraphs instead of clearly laid out in bullet points.

The charts you filled in during your active reading might look like the ones below. (Of course, given the limited time you have on the test, yours would contain a lot of short forms and abbreviations.)

Pro side (flyer):

Con side (warning):

Now you have a bare bones list of the evidence you need. Each side presents four arguments, all of them supported. Two of the arguments are contradictory (weight loss/weight gain). Which passage is better supported?

Although an effective argument can be created for either passage, for this example let’s say you choose the warning. You might choose this one because it cites one study (as the flyer does), but also gives specific figures (the nuts and carbs) for two other arguments. Its author is familiar enough with the diet to know that it doesn’t include advice on balanced nutrition. (Showing an understanding of the other side’s position boosts credibility.) The warning’s support is more specific and credible than the support offered in the flyer, too. In two cases, the flyer supports arguments with only the vague experiences of unidentified “followers” of the diet.

The strongest reason for choosing the warning side, though, could lie in the authors and their purposes. The flyer’s author is trying to promote a seminar, and is making the assumption that urban cave dwellers want to eat like the real thing—not necessarily a valid assumption. The promotional tone of the flyer and the benefits offered (free food samples, video) undercut the credibility of the “pro” side’s argument. The warning’s author, on the other hand, has the credibility of being a medical professional. This author’s purpose is to prevent the clinic’s patients from damaging their health with a harmful diet, and the underlying assumption that patients are concerned about their health is valid.

From the chart, you can see that you’ll end up with a six-paragraph essay: the introduction (the beginning), one paragraph for each of the four arguments (the middle), and a conclusion (the end).

You have two choices for the order in which you’d discuss the arguments. You could stick with the order in which they’re listed in the better-supported passage you’ve chosen (the warning), or else start with the warning’s strongest argument (either the heart issue, which is supported with a specific study, or else the low athletic performance, which would be important to the warning’s audience). Here, too, there is no right or wrong answer; choose the order you think you could do the best job of covering in the middle four paragraphs. Remember to start each paragraph with a topic sentence and use transitions (such as “in addition” or “furthermore”) to guide readers smoothly through your discussion of the four pieces of evidence.

Now you’ve got everything you need to write your essay. You have your thesis (that the warning provides the best support), the evidence that supports your thesis (the arguments from the chart), and the template to follow in presenting your points. So let’s get started on the writing.

The Introduction This example would work well with a question attention-getter:

Should modern urban cave dwellers and athletes be eating like Paleolithic man?

Then you would tie that question to the topic of your essay, state your thesis, and give the big picture outline of the arguments:

The promoter of a Paleo diet seminar thinks they should. However, a sports medicine clinic’s warning about the diet’s nutritional, health, and athletic dangers is better supported than the arguments in favor of eating like our ancient ancestors.

The Middle Here you’d give the evidence from the passage (one argument per paragraph), and explain why it proves your thesis that the case against the Paleo diet is better supported.

For instance, if you’re following the order used by the better-supported side, you would begin with the evidence about nutritional imbalance, which is supported by a medical professional’s familiarity with the Paleo diet and its lack of guidance about nutrition. You could also point out the weakness of the corresponding argument from the seminar promoter: The vague statements about a natural rotation of nutrients and not overworking the digestive system aren’t credible from someone who isn’t a professional nutritionist.

The next three paragraphs would deal with the next three arguments, always explaining how each one contributes to proving your thesis that the warning is better supported.

The End Here you would restate your thesis in different words, and remind readers of the main pieces of evidence that prove your thesis. This concluding paragraph might say something like this:

Based on the credibility of the medical professional who wrote the warning and the specific support for the arguments given, the case against the Paleo diet is better supported. Detailed figures back up the arguments about health dangers (weight gain and cardiovascular problems) as well as the argument about lower athletic performance. This author has also made the effort to learn about the Paleo diet, and has noted its failure to provide nutritional guidance. The seminar promoter, on the other hand, cites only one study and is clearly trying to entice people to attend by mentioning the goodies that will be available.

Now, while you’re practicing, you have time to ask yourself the questions listed in Chapter 10 (see this page) to assess your own work. During the test, of course, you won’t. Then, you’ll simply be reviewing your essay to revise it (is something not clear? is there a better way to say it?) and edit it (correcting grammar or spelling errors).

Now you try building and organizing your argument and writing an essay on your own. There are two Extended Response tasks below. (Remember, the more practice you get, the better you’ll become at doing these essays.)

The first task, about electric vehicles, will give you some experience digging evidence out of the text paragraphs in two very different types of documents. The second, about antibiotics in farm animal feed, provides an example of unequally weighted evidence (one main argument on one side, several on the other). Depending on your opinion about this issue, it might also allow you to exercise the discipline of arguing for a position with which you don’t agree.

Use active reading to extract the authors’ arguments and support as you read, and note them in a chart. Then plan, write, and review your essay. Use the questions listed in Chapter 10 (see this page) to assess your own work. Then read the suggestions in Part VIII: Answer Key to Drills.

Below are two passages: a government document about the benefits of electric vehicles and a letter from a father to his daughter, urging her not to buy an electric car because of the dangers.

Passage summary:

While the U.S. Department of Energy lists the benefits of electric vehicles, the father’s letter to his daughter outlines the dangers.

The prompt:

In your response, analyze both the government document and the letter to determine which position is better supported. Use relevant and specific evidence from both sources to support your argument.

Type your response in the box below. This task may require approximately 45 minutes to complete.

Passage A

The following document uses these short forms (or acronyms) in discussing different types of vehicles powered by electricity: EV (electric vehicle), HEV (hybrid electric vehicle) and PHEV (plug-in hybrid electric vehicle).

Benefits and Considerations of Electricity as a Vehicle Fuel

1 Hybrid and plug-in electric vehicles can help increase energy security, improve fuel economy, lower fuel costs, and reduce emissions.

Energy Security

2 In 2012, the United States imported about 40% of the petroleum it consumed, and transportation was responsible for nearly three-quarters of total U.S. petroleum consumption. With much of the world’s petroleum reserves located in politically volatile countries, the United States is vulnerable to price spikes and supply disruptions.

3 Using hybrid and plug-in electric vehicles instead of conventional vehicles can help reduce U.S. reliance on imported petroleum and increase energy security.

Fuel Economy

4 HEVs typically achieve better fuel economy and have lower fuel costs than similar conventional vehicles.

5 PHEVs and EVs can reduce fuel costs dramatically because of the low cost of electricity relative to conventional fuel. Because they rely in whole or part on electric power, their fuel economy is measured differently than in conventional vehicles. Miles per gallon of gasoline equivalent (mpge) and kilowatt-hours (kWh) per 100 miles are common metrics. Depending on how they’re driven, today’s light-duty EVs (or PHEVs in electric mode) can exceed 100 mpge and can achieve 30–40 kWh per 100 miles.

Infrastructure Availability

6 PHEVs and EVs have the benefit of flexible fueling: They can charge overnight at a residence (or a fleet facility), at a workplace, or at public charging stations. PHEVs have added flexibility, because they can also refuel with gasoline or diesel.

7 Public charging stations are not as ubiquitous as gas stations, but charging equipment manufacturers, automakers, utilities, Clean Cities coalitions, municipalities, and government agencies are establishing a rapidly expanding network of charging infrastructure. The number of publicly accessible charging units surpassed 7,000 in 2012.

Costs

8 Although fuel costs for hybrid and plug-in electric vehicles are generally lower than for similar conventional vehicles, purchase prices can be significantly higher. However, prices are likely to decrease as production volumes increase. And initial costs can be offset by fuel cost savings, a federal tax credit, and state incentives.

Emissions

9 Hybrid and plug-in electric vehicles can have significant emissions benefits over conventional vehicles. HEV emissions benefits vary by vehicle model and type of hybrid power system. EVs produce zero tailpipe emissions, and PHEVs produce no tailpipe emissions when in all-electric mode.

Source: Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE), U.S. Department of Energy (Abridged)

Passage B

10 My dear Melissa:

11 I’m so proud of you for completing your dental technician course and graduating with such exceptional grades!

12 As promised when you first returned to school, I’m transferring enough money to your account to allow you to buy a reasonably priced new car. You deserve this reward for your perseverance and hard work.

13 The choice of car is up to you. However, I know you want to “live green” and I’m concerned you might be thinking of an electric vehicle. If you are, I want to urge you to buy a regular gasoline-powered car instead. Your safety is very important to me, and there are just too many dangers with an electric vehicle.

14 First, you could find yourself stranded on a dark highway in the middle of nowhere. Electric cars have such a limited range (an average of about 80 miles) and even the state with the most public charging stations, California, has only about 5,000. Assuming you can find a public charging post when you need one, a charge can take hours if it’s not a rapid-charge station. I have visions of you hanging around some station alone at night for up to eight hours.

15 Second, parts and repairs for electric cars are much more expensive. And the batteries need to be replaced after about five years, at a cost of thousands of dollars. That’s on top of the initial price of the car, which can be as much as twice the cost of a gasoline-powered car.

16 Third, with a top speed of about 70 miles per hour, electric cars aren’t safe for highway driving. What if you had to pass someone quickly, or speed up suddenly to get away from a dangerous situation? That means you wouldn’t be able to drive home to visit your mother and me.

17 And finally, I’ve been seeing news reports of a few electric vehicles catching on fire while they’re just sitting in the owner’s garage or driveway. No one seems to know what causes them to ignite, but I don’t want to be worrying about you every night asleep in your ground-floor apartment while your car is burning away just outside.

18 I hope you enjoy your well-deserved reward, and that you’ll use it wisely and choose a gasoline-powered car.

19 Your loving father.

Below are two passages: a government media release about a voluntary ban on antibiotics in farm animal feed, and a posting on a farmers’ online forum warning about the negative effects such a ban would have on farmers, consumers, and the economy.

Passage summary:

While the U.S. FDA media release explains why it wants to eliminate antibiotics in farm animal feed, the online forum posting urges readers to sign a petition against the ban.

The prompt:

In your response, analyze both the media release and the forum posting to determine which position is better supported. Use relevant and specific evidence from both sources to support your argument.

Type your response in the box below.

Passage A

1 The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is implementing a voluntary plan with industry to phase out the use of certain antibiotics for enhanced food production.

2 Antibiotics are added to the animal feed or drinking water of cattle, hogs, poultry, and other food-producing animals to help them gain weight faster or use less food to gain weight.

3 Because all uses of antimicrobial drugs, in both humans and animals, contribute to the development of antimicrobial resistance, it is important to use these drugs only when medically necessary. Governments around the world consider antimicrobial-resistant bacteria a major threat to public health. Illnesses caused by drug-resistant strains of bacteria are more likely to be potentially fatal when the medicines used to treat them are rendered less effective.

4 FDA is working to address the use of “medically important” antibiotics in food-producing animals for production uses, such as to enhance growth or improve feed efficiency. These drugs are deemed important because they are also used to treat human disease and might not work if the bacteria they target become resistant to the drugs’ effects.

5 “We need to be selective about the drugs we use in animals and when we use them,” says William Flynn, DVM, MS, deputy director for science policy at FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM). “Antimicrobial resistance may not be completely preventable, but we need to do what we can to slow it down.”

6 Once manufacturers voluntarily make these changes, the affected products can then be used only in food-producing animals to treat, prevent, or control disease under the order of or by prescription from a licensed veterinarian.

7 Bacteria evolve to survive threats to their existence. In both humans and animals, even appropriate therapeutic uses of antibiotics can promote the development of drug-resistant bacteria. When such bacteria enter the food supply, they can be transferred to the people who eat food from the treated animal.

Why Voluntary?

8 Flynn explains that the final guidance document made participation voluntary because it is the fastest, most efficient way to make these changes. FDA has been working with associations that include those representing drug companies, the feed industry, producers of beef, pork, and turkey, as well as veterinarians and consumer groups.

Source: U.S. Food and Drug Administration (Abridged)

Passage B

The following posting appeared on the FairToFarmers.org forum.

Ban the FDA’s Antibiotic Ban!

9 The FDA is banning the use of antibiotics in animal feed. Food producers will be barred from adding antibiotics to feed or water unless an animal is sick and threatens the health of the rest of the herd or flock. Even then, a veterinarian’s order will be required.

10 The FDA fails to realize that the regular use of antibiotics prevents disease, and prevention is much cheaper than curing an illness that has taken root on the farm. Antibiotics not only maintain animal health; they also promote faster growth, and therefore faster time to market. In addition, antibiotics lead to more efficient growth, since less feed is required to reach the desired weigh.

11 The FDA’s reasoning is that antibiotic use in food animals might contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant “superbugs.” Scientific studies have so far been inconclusive, and some point to doctors overprescribing antibiotics for human patients as the cause, together with unsafe food handling practices by consumers. The FDA made the ban voluntary for the present; but if the scientific evidence were clear, the ban would have been mandatory right away.

12 European countries that have banned antibiotics in animal feed have not seen a decline in antibiotic-resistant diseases, but they have seen a significant increase in meat and poultry prices and a reduction in export sales. Food animals take several days longer to reach the desired weight and consume more feed before they do, increasing farmers’ costs.

13 Each American farmer today feeds an average of 155 people, six times more than in 1960. Advances in agricultural practices, including the regular use of antibiotics in animal feed, have made that possible. Without antibiotics, American farmers will not be able to meet the food needs of a growing population.

14 Do people want enough food? Do they want affordable food? Do politicians want a thriving agricultural economy? Then we must end this voluntary ban on antibiotics in animal feed while we still can, before it becomes mandatory.

15 Add your voice to the petition to ban the FDA’s ban on antibiotics in animal feed. Simply click on the button below. The petition will be delivered to the FDA when we have 100,000 signatures.

Petition to Ban the FDA Ban on Antibiotics in Animal Feed

The Extended Response section combines the active reading, critical thinking, and language use skills that are required for the Reading and Language assessments.

You will have 45 minutes to

analyze two passages (about 650 words total) that present opposing sides of a “hot button” issue

decide which position is better supported

explain your choice in an essay, using evidence drawn from both passages

revise and edit your work

The essay is considered an “on demand draft” and is not expected to be completely free of errors.

There is no required length or number of paragraphs.

There are no spelling or grammar checkers. You can cut, copy, and paste within the text box where you type your essay, but you can’t copy text from the passage and paste it into your essay.

There is no right or wrong answer, as long as you build a credible case for the best-supported passage and back it up with evidence from the passages.

Look for evidence in the authors’ arguments for their positions and in the support (such as studies or statistics) they provide for their arguments. Also judge the authors’ reasoning and assumptions.

The essay is graded by an automated scoring engine that has “learned” how humans graded an extensive range of sample essays. If it doesn’t recognize the characteristics of an essay, it assigns the work to a human grader.

The essay is assessed on how well you

create your argument and use evidence from the passages

develop and organize your ideas

use language

Divide your time efficiently.

During the first five minutes, use active reading to build your case for which passage is better supported. Note each author’s arguments and how the authors support them.

Take the next five minutes to plan your essay.

Spend about 32 minutes writing what you planned.

Allow three minutes at the end to revise and edit your work.

Use an essay template to organize your ideas.

The Beginning

—Introductory paragraph

—Attention-getter (optional)

—Thesis statement (which passage is better supported)

—Big picture list of evidence that proves the thesis statement

The Middle

—One paragraph for each piece of evidence that proves the thesis statement

—Topic sentence

—Evidence from the passages

—Explanation of how the evidence supports the thesis statement

The End

—Restatement of the thesis in different words

—Reminder of the pieces of evidence that prove the thesis

Improve your writing by

reviewing the eight areas of language use explained in Chapter 8

starting each paragraph with a topic sentence

using active verbs

varying the structure and length of your sentences

revising and editing your work