In this chapter, you will learn how to

• Explain the need for and the importance of an investigative report, describe how a report is classified, discuss the salient features of a good report, and describe best practices for investigators

• Summarize the guidelines for writing a report, provide an overview of the investigative report format, and provide a layout for an investigative report

• Provide a computer forensic report template, show how to document a case report, and demonstrate how to write a report using FTK and ProDiscover

• Define an expert witness, explain the role of an expert witness, and describe various types of expert witnesses, as well as how to find a computer forensic expert

• Explain the differences between a technical witness and an expert witness, articulate the scope of expert witness testimony, and recall the rules pertaining to an expert witness’s qualifications

• Recall the steps involved in processing evidence and preparing a report

• Testify in court during direct and cross-examination and explain the general ethics applicable when testifying

There’s an old saying that “the job ain’t finished until the paperwork’s done.” This certainly is the case with digital investigations. As a digital forensics investigator (DFI), you’ve been assigned to investigate a particular situation and report your conclusions, regardless of whether you’ve been hired as an independent consultant, you’re a member of law enforcement, or you’re part of an investigative team for an organization. In some cases, your report may initially be a verbal response to a decision-maker, followed by a written report or presentation to upper-level management or to your peers. If you’ve been hired as part of legal proceedings, you may be asked to appear in court as a witness.

We’ve already discussed the format of a preliminary summary of findings, sometimes called a threshold assessment.1 Since these are preliminary reports, they may contain various avenues for further investigation, depending on evidence yet to be discovered. A formal investigative report will contain more details regarding the evidence, as well as firmer conclusions based on that. The key difference between a threshold assessment and an investigative report is that an investigative report will confine itself to the evidence discovered, while a threshold assessment will focus on other areas of investigation based on the evidence gathered to date. Figure 12-1 shows a common format for a threshold assessment.2

Figure 12-1 Threshold report format (Adapted from Casey, E. et. al., Digital Evidence and Computer Crime, 3rd ed. (MA: Elsevier, 2011).)

An interesting aspect of this report is the section on victimology, the “investigation and study of victim characteristics.”3 Understanding the characteristics of the victim may provide a clue to the perpetrator’s methods and predilections; the time just prior to the incident may reveal other activities of the suspect that may put them in contact with the victim. Another characteristic of a threshold report is that the investigation may be halted at that point. Enough evidence may have been found to support the case, or further investigation may be unwarranted because of cost or difficulty in obtaining more evidence.

Depending on the organization where you are employed as a DFI, you can reasonably expect to be called as a witness in a court case. Your role as a witness may be to act as a technical or evidentiary witness, or as an expert/scientific witness. Regardless of how and when you are testifying, presenting, or writing a report, always remember who your audience is. Your presentation and style can and should vary depending on whether you are presenting a paper at a technical conference, reporting information to an attorney, or testifying under oath. Are you attempting to communicate information, or are you attempting to persuade someone to adopt your point of view? Are you talking to your peers or to senior management?

As a technical/scientific witness, you are called to support the facts of the case. You will be asked to speak to the nature of the evidence, as well as how that evidence was obtained. You will not be asked to express an opinion or conclusions. (“Just the facts, ma’am,” as Jack Webb of TV’s Dragnet used to say.)

An expert witness has a very different role to play in legal proceedings. The phrase “expert witness” has a specific meaning within the legal profession. An expert witness is called specifically to offer an opinion of the evidence, as well as to draw conclusions based on that evidence. Although expert witnesses come in all shapes, sizes, and areas of expertise, the scope of the testimony of an expert witness should be solely within the bounds of his or her expertise. As a DFI, it’s not your job to explain the law or to detail the minutiae of why SHA-256 is different from MD5. In some engagements, appearing in court may not be necessary, in that you may be hired as a consultant who works with the attorney, and thereby act as a consulting witness. Regardless, you will need to generate a report, and you may be required to provide testimony in the form of a deposition during the discovery phase of the legal process or a testimony preservation deposition.

Two significant cases have defined the rules for expert witness testimony. The first case was Frye v. United States, 293 F. 1013 (D.C. Cir. 1923). In this case, the court ruled that testimony is inadmissible unless it is “testimony deduced from a well-recognized scientific principle or discovery; the thing from which the deduction is made must be sufficiently established to have gained general acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs.”4 The second case was Daubert v. Merrell Down Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1933). Daubert was significant in that it established a set of principles to use to determine if expert witness testimony was reliable.

Daubert set forth a nonexclusive checklist for trial courts to use in assessing the reliability of scientific expert testimony. The specific factors explicated by the Daubert Court are

1. whether the expert’s technique or theory can be or has been tested—that is, whether the expert’s theory can be challenged in some objective sense, or whether it is instead simply a subjective, conclusory approach that cannot reasonably be assessed for reliability;

2. whether the technique or theory has been subject to peer review and publication;

3. the known or potential rate of error of the technique or theory when applied;

4. the existence and maintenance of standards and controls; and

5. whether the technique or theory has been generally accepted in the scientific community.

The Court in Kumho (526 U.S. 137, 119 S.Ct 1167) held that these factors might also be applicable in assessing the reliability of nonscientific expert testimony, depending upon “the particular circumstances of the particular case at issue.”5

Depending on the state in which you practice, courts may use either Daubert or Frye as a standard for determining expert witness testimony.

EXAM TIP You will need to know the difference between Frye and Daubert. In essence, Daubert provides a set of criteria for determining whether scientific testimony is admissible; Frye is more general.

If you are going to testify as an expert witness, you will need to meet those standards set forth for expert witness testimony. These standards are outlined in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) 26(a)(2) and the Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) 702, 703, and 705. FRCP 26(a)(2) simply states that an attorney must specify the identity of someone they intend to call as a witness, as well as the evidence that the witness has available to them.

FRE articles 702, 703, and 705 address the qualifications of an expert witness and the basis of how the witness came to arrive at a particular conclusion. Rule 702 addresses the qualifications and the conditions under which a witness can testify:

A witness who is qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may testify in the form of an opinion or otherwise if:

a. the expert’s scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will help the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue;

b. the testimony is based on sufficient facts or data;

c. the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and

d. the expert has reliably applied the principles and methods to the facts of the case.

FRE 702 effectively summarizes the principles laid out in Daubert. FRE 703 lays out the basis for an expert witness’s opinion and testimony. I myself find it interesting that the opinion can be admitted as evidence even though facts or data are not!

An expert may base an opinion on facts or data in the case that the expert has been made aware of or personally observed. If experts in the particular field would reasonably rely on those kinds of facts or data in forming an opinion on the subject, they need not be admissible for the opinion to be admitted. Nevertheless, if the facts or data would otherwise be inadmissible, the proponent of the opinion may disclose them to the jury only if their probative value in helping the jury evaluate the opinion substantially outweighs their prejudicial effect.

Last, FRE 705 speaks to disclosing the facts or data underlying the expert opinion and clarifies FRE 203. “Unless the court orders otherwise, an expert may state an opinion—and give the reasons for it—without first testifying to the underlying facts or data. But the expert may be required to disclose those facts or data on cross-examination.”6

An expert witness is more than a subject matter expert (SME). FRCP 26(2)(b) defines who has to supply a written report and the contents of that report. We’ll address the content of the report later on this chapter. For now, we’ll focus on the applicable history and experience required for an expert witness. Items 4, 5, and 6 of 26(2)(b) indicate that the witness must provide a list of other cases in which they’ve testified/been deposed in the preceding four years and ten years of published writing, as well as any previous compensation they have received for testifying.

This means that an expert witness needs to have an up-to-date curriculum vitae (CV). The CV should demonstrate how the witness has enhanced their skills via “training, teaching, and experience.”7 The CV describes tasks that the witness has performed that demonstrate particular accomplishments, and it should contain a list of basic and advanced skills and how they were obtained. The CV also should include general and professional education, such as courses sponsored by people who train government agencies, courses offered or sponsored by professional organizations, and training to which the witness has either contributed or provided. A CV is similar to a resume, but doesn’t focus on a particular trial. Rather, the CV is more like a skills-focused resume that attests to skills, abilities, and knowledge rather than justifying one’s suitability for particular employment.

For civil cases, U.S. district courts require an expert witness to submit reports. Federal courts require that all scientific, technical, or expert witnesses must provide a report prior to trial in civil cases, as indicated in FRCP 26(2)(b). FRCP 26(2)(b) also states that a report must contain

• All opinions

• The basis for the opinions

• Information considered in forming those opinions

Appendices should include

• Related exhibits, such as photos or diagrams

• Expert witness’s CV

Actually preparing the report usually involves organizing your supporting evidence to write that report. Ensure that your CV is up to date. Organize the related exhibits into appendices that reflect the evidence used to support your opinions. For each stated opinion, make sure that you have the evidence available on which you based your opinion and any references to outside studies or techniques that you used to reach those opinions. Make sure as well that your outside sources or techniques meet the criteria laid out in Daubert for accuracy and acceptance by your peers.

The majority of work in preparing evidence for testimony should have been completed before you started writing the report and preparing your testimony. Two things need to be accomplished: preparing an examination plan and organizing the presentation materials for your testimony.

An examination plan is a guideline regarding the questions that you can expect your attorney to ask you in the process of testifying.8 One important aspect of this plan is that it allows you to make changes to the questions that the attorney may ask, and it allows your attorney to gain familiarity with digital forensics if they have no prior knowledge. Look at the examination plan as a way to improve communication between you and your attorney.

Depending on the results of the examination plan, you may decide to prepare some “visual aids” as part of your testimony. Diagrams, maps, photographs, and so on can support your verbal testimony by making it noteworthy.

Remember to use good presentation style: no more than 3 bullet points per slide, a font large enough to be seen anywhere in the room and no extraneous decorations. If permitted, provide handouts for judge, jury, and both attorneys. Make eye contact, and always face your audience.

Ethics are codes of professional conduct or responsibility. Ethics help you, as a professional, to control your bias. Everyone has a bias in one form or another; the key to managing those biases is to become aware of them and learn how to present evidence calmly and objectively.

Nelson lists three sources of ethics.9 Foremost are your internal values, derived from your upbringing, personal independent experience, religion, morals, culture, and so forth. Many professional certifying bodies also list a code of conduct or ethics, and many professional associations do as well. EC-Council has its own code of ethics for those who achieve their certifications, and these are listed here:

Three certifying organizations stand out for a DFI:

• The EC-Council offers the Computer Hacking Forensic Investigator (C|HFI) certification. The EC-Council Code of Ethics applies to anyone who earns one of their certifications, including the Certified Ethical Hacker (C|EH).

• The International Society of Forensic Computer Examiners (ISFCE) at www.isfce.com provides a Code of Ethics and Professional Responsibility. ISFCE offers the Certified Computer Examiner (CCE) examination both for individuals in law enforcement and for others.

• The International Association of Computer Investigative Specialist (IACIS) at www.iacis.com offers the Certified Forensic Computer Examiner (CFCE) certification and the Certified Advanced Windows Forensic Examiner (CAWFE) certification. Both of these exams include a written examination and a practical examination or assessment.

Other professional associations may be important to your career as a DFI, depending on your area of specialization. These associations include the American Bar Association (ABA), the American Medical Association (AMA), and American Psychological Association (APA). All of these associations have codes of conduct and ethical behavior, and it’s a good idea to know what these ethical standards mean for each of these professions since, as an expert witness, you may be working with other individuals from these professions.

In sum, a DFI has a duty to appear impartial and to present (or at least not ignore) any exculpatory evidence found during the investigation and analysis.

As an expert or technical witness, you can expect to participate in multiple phases of a court case. These phases are prior to the trial, during the trial, and after the trial has concluded (although the case may be appealed further). Although circumstances differ among these three phases, one aspect is clear: Don’t discuss the case with others except for your client (usually an attorney). These next two sections address concerns that are specific to the first two phases. We’ll look at after the trial a bit later on in this chapter.

Prior to Trial There are several things that you should observe in the preliminary events leading up to the actual trial. First, keep your own counsel (no pun intended): remember, your client is the attorney who hired you the case at which you will testify). Don’t discuss the case with other people or express your opinions. Practice saying “no comment” to members of the media. Avoid conflicts of interest: these could arise if you develop a personal relationship with the opposing attorney, or you become involved in activities where the outcome of the case could benefit you. Finally, get paid before you testify. If you don’t, the opposing attorney can suggest that you’re being paid based on the outcome of the case, and not for the work that you had done in preparation for testifying.

When actually testifying, your effect will be determined by both what you say and how you say it. Consider the following suggestions as best practices:

• Always remain professional in both dress and demeanor. That is, dress professionally based on the standards of the community in which you’re appearing. Cowboy boots may be acceptable attire in Austin, Texas; they would appear eccentric at best in Boston, Massachusetts. All night partying will demonstrate a lack of seriousness on your part, and a hung-over witness won’t appear credible.

• Practice beforehand. Prepare answers to standard questions based on your expertise and in consultation with your attorney.

• Address the audience directly, regardless of who it is (judge, jury, opposing counsel). Prepare for, and adjust your presentation to, your audience based on their educational and vocational background.

• Be prepared to stay within the scope of your expertise; if the question is outside that scope, say so. In addition, indicate if you weren’t asked to investigate a particular aspect of the case. If in doubt about the direction or intent or meaning of a question, simply ask that the question be repeated.

During the Trial Court testimony includes both direct examination and cross-examination. During direct examination, you can expect to present information, testify, or attest to facts based on three things11:

• Independent recollection (what you know about this case and others without prompting)

• Customary practice (procedures that are traditionally followed in similar cases)

• The documentation of the case (written records you’ve maintained)

As an expert witness, you don’t need to have been involved in the case from the beginning. Rather, you are basing your opinion on the evidence gathered as part of the investigation rather than direct participation in that investigation.

During cross-examination, don’t appear to be too friendly or too hostile with the opposing attorney. Maintain your composure. During the course of the trial, maintain a professional distance and a professional decorum. Don’t talk to anyone during a court recess; if you need to have a conversation with your attorney, do so in private so that your conversation doesn’t become an issue during cross-examination. If you should find exculpatory evidence during the trial, report it immediately to your attorney. Hopefully, any exculpatory evidence will be found well before the case goes to trial, but you have an ethical responsibility to report this evidence whenever it is discovered.

Other Proceedings You can participate in legal proceedings in other ways than appearing at a trial as a witness. You may be called to testify at a hearing, whether an administrative hearing or a judicial hearing. An administrative hearing takes place in front of an administrative agency, either state or federal. Judicial hearings usually occur prior to the case going to trial, and focus on whether evidence will be found to be admissible. These kinds of hearings are very much like testifying at a trial, and it’s particularly important that you have your methods of evidence collection and preservation down pat.

Depositions are yet another form of testifying. There are discovery depositions and testimony preservation depositions. As you might expect, the discovery deposition is part of the overall discovery process for a particular trial. Usually, both attorneys are present. Be aware that in the U.S. adversarial justice system, the opposing attorney may use several means to discredit your testimony. This can include peppering you with questions, asking complex hypothetical questions, or acting aggressively and combative. Keep in mind as well that an attorney will have access to testimony that you have provided in previous cases through services that provide access to libraries of testimony called deposition banks. Make sure that you haven’t refuted your own testimony! If your opinions have changed, be prepared to state why.

A testimony preservation deposition is a way of preserving testimony in case you would not be able to testify later. In some instances, the testimony may be videotaped; in other instances, the testimony preservation may take the form of a demonstration of techniques used to produce that evidence.

Regardless of when and where you provide testimony, follow these simple rules:

• Be professional and polite.

• Just the facts.

• Keep cool; don’t become flustered or rattled.

In addition, what is good, Phaedrus, and what is not good?

Need we ask anyone to tell us these things?12

Whether you have been hired simply to undertake an investigation or you are asked to appear as a witness, you will need to produce a report of your findings. The exact format of this report will vary depending on your audience and the method of delivery. Regardless of these conditions, a report must be effective. An effective report is one that provides the necessary supporting information to persuade a particular audience of the accuracy of the report’s conclusions. FRCP 26(2)(b) indicates that a report must include13

• A complete statement of all opinions the witness will express and the basis and reasons for them

• The facts or data considered by the witness in forming them

• Any exhibits that will be used to summarize or support them

Therefore, an effective report provides details that document and illustrate the investigation. Usually, the client (an attorney or another investigator) defines the goal of the investigation. An effective report ultimately supports that goal. A good report is thus an effective report, and a report is good when it covers the essential elements of the investigation.

Remember that the primary goal of a technical report is to communicate information. You can improve communication by using a simple format, avoiding slang or technical jargon, and taking care to expand a TLA when used (TLA stands for a three-letter acronym such as NSA, FBI, or DOJ). Avoid hypothetical questions, but do use theoretical questions as a way to structure your narrative and as a way to demonstrate how the evidence supports and answers this question.

Although you may use a particular template for all your reports, each report must be specific to a particular incident and uniquely identify that incident. Here’s where your documentation of the crime scene, the tagging and bagging of evidence, and your chain-of-custody documentation all come into play. These materials will help you provide a consistent and well-organized description of how the evidence was collected, preserved, and analyzed.

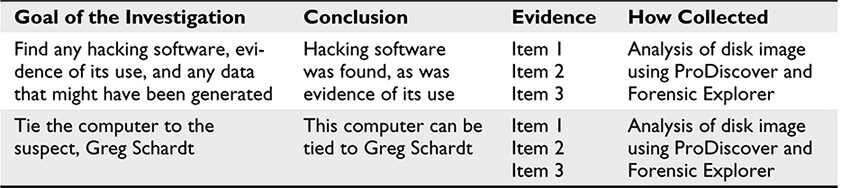

One effective technique for determining the consistency of reports is to match the goals of the investigation with the evidence that you’ve produced. Let’s return to the case of Greg Schardt, aka Mr. Evil. Our goals for that investigation were twofold: demonstrate that Greg Schardt and Mr. Evil were one and the same (putting the person, Greg Schardt, in front of the keyboard when logged in as Mr. Evil), and demonstrate that Mr. Schardt had been cracking wireless network traffic in order to gain login credentials and passwords.

We can express our results in Table 12-1, which is loosely based on the notion of a requirements traceability matrix from the software engineering discipline. A technique like this can provide you with assurance that you have addressed the goals of the investigation and your conclusions are supported by the evidence collected.

Table 12-1 Evidence Traceability Matrix

The EC-Council offers the following as an example of an investigative report template.14 I’ve taken the liberty of rearranging and editing the different topics to clarify the organization of the report.

I. Summary

1. Case number

2. Names and Social Security numbers of authors, investigators, and examiners

3. Purpose of investigation

5. Signature analysis

II. Objectives of the investigation

III. Incident description and collecting evidence

1. Date and time the incident allegedly occurred

2. Date and time the incident was reported to the agency’s personnel

3. Name of the person or persons working the investigation

4. Date and time investigation was assigned

5. Nature of claim and information provided to the investigators

6. Location of the evidence

7. List of the collected evidence

8. Collection of the evidence

9. Preservation of the evidence

10. Initial evaluation of the evidence

IV. Investigative techniques

V. Analysis of the computer evidence

VI. Relevant findings

VII. Supporting expert opinion

VIII. Other supporting details:

1. Attacker’s methodology

2. Users’ applications

3. Internet activity

IX. Recommendations

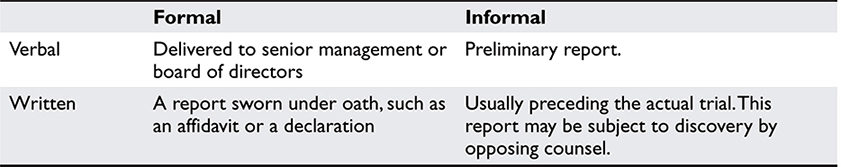

How you intend to deliver the report will affect the preparation. We can classify reports as formal or informal, verbal or written. Table 12-2 describes each type of report.

Table 12-2 Forensics Report Types

Formal reports are more structured and are more likely to follow a set format. If you are delivering a formal verbal report, make sure that it follows your examination plan. If you’re delivering a formal written report, such as what is required for submission to a court, make sure you follow the outline or format that is required for these documents. Once again, consistency is critical here.

TIP Choose a report format that you like and use it for all your reports. It’s better to label as section as “not applicable” (NA) and the reasons why you believe it’s inapplicable rather than skip the section entirely.

An example of an informal verbal report is a status report provided to someone in the attorney’s office. A written informal report could be a more detailed description of the entire case (an investigative report would fall under this heading). This kind of report is subject to discovery by an opposing attorney. Destroying the report might be considered destruction of or the concealment of evidence, also known as spoliation, defined as “the destruction or alteration of a document that destroys its value as evidence in a legal proceeding.”15

A well-written report tells a story that answers the 5WH (who, what, when, where, why, how) questions.16 Your narrative is supported by including figures, tables, data, and equations. All of these can and should be referenced in the text: In some cases, they can be inserted inline with the text itself. Each type of display should be numbered separately with a section identifier and an element number (for example, “Figure 5-2 shows the suspect’s desktop including the wireless router and the attached printer.”). Avoid using precise placement terms (preceding, following) because the display element may be repositioned when the report is actually printed.

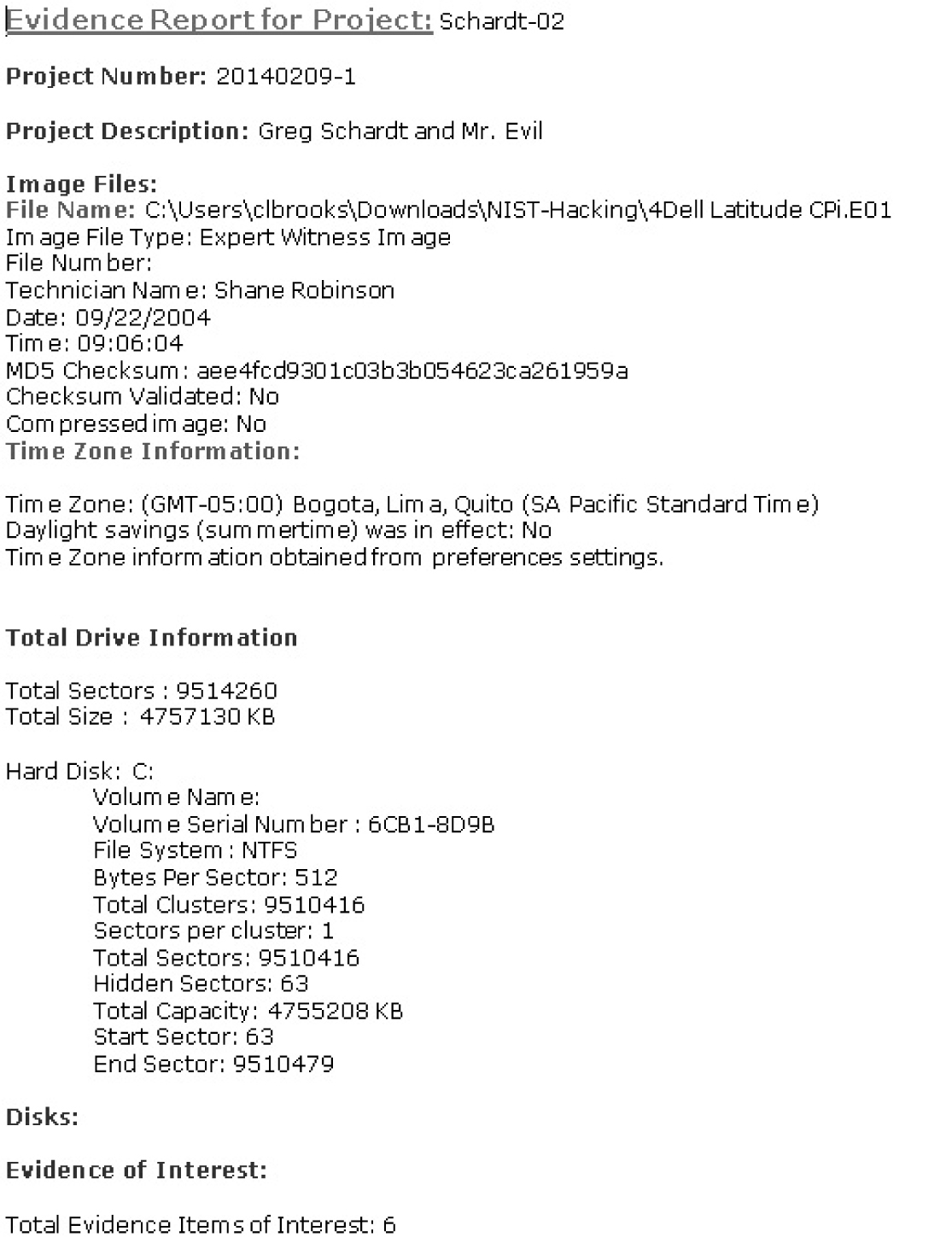

Figure 12-2 ProDiscover Basic report output

The key element in report preparation is consistency. Using a template can help you keep your presentation internally consistent, in addition to enforcing consistency across all reports. A very general template might include these sections17:

I. Abstract or summary

II. Table of contents

III. Body of report

IV. Conclusions

V. References

VI. Glossary

VII. Acknowledgments

Sections can be numbered using either a decimal numbering system, such as

1. Analysis

1.1. Preliminary analysis

1.1.1. Research

1.1.2. Examination plan

1.2. Onsite Investigation

2. Conclusions

or a legal-sequential numbering system, such as

I. Analysis

1. Preliminary analysis

2. Onsite investigation

II. Conclusions

Your client or your organization may have a preferred style for reporting, and you should use that format unless there is a very good reason not to (and be prepared to support your argument as to why the standard format isn’t suitable).

Looking back, we can see that the section labeled as the body of the report contains the important explication of the collection and analysis of the evidence. This section should contain information about methods used to solve the problem, including how the data was collected, special tools or techniques used, statistical methods used, and so on. Refer to any tools used to complete your calculations (MATLAB, for example, or the R statistical package).

The body of the report and the conclusions are the most important sections. Going backwards, a good report will present conclusions that have been supported by the description of collecting the evidence and performing the analysis. Written correctly, your conclusions will flow seamlessly from the presentation of the evidence, creating a story that can only have one ending.

The report body should address how you went about collecting and analyzing the data, including how the data was collected, any special tools or techniques used, statistical methods used, and so on. Make sure to refer to any tools used to complete your calculations (MATLAB, for example, or the R statistical package). Knowing the accuracy and reliability of the tools you’ve used is crucial to standing up to cross-examination from the opposing attorney. Your report should contain information on error analysis and how certain the results of that tool are. Addressing uncertainty enhances the integrity of your data and your presentation by establishing that you know the limitations of a particular tool. Timestamp analysis, for example, is uncertain because time stamps can be altered. Likewise, document metadata may be inconsistent or confusing (we may have lost the indication of who made the change between version 1 and version 3, for example). Establishing that immediately heightens your credibility because it indicates that you have taken this uncertainty into account while performing your analysis.

Collected evidence are of three kinds. General evidence is the description of who did what to whom, when, and where (that is, the date and time you visited the site, with whom you spoke, and so forth). Physical and demonstrative evidence is the actual digital forensics evidence you collected, and all the records associated with that evidence: what was seized, how it was protected, who had access (chain of custody). Finally, testimonial evidence is the record of your conversations with people: names, date and time, organization, their position within the organization. If you’re working with law enforcement, and the interviewee was a suspect, you should include a statement that the person received a Miranda warning.

Before submitting the report, make a final run-through. Only relevant material should be included. Make sure you have used a consistent structure and you haven’t repeated yourself. If possible, have someone unfamiliar with the case read the report as a test to determine if it can be understood by an outsider.18 Pay attention to the mechanics of the report: Check grammar, spelling, punctuation, and readability (most word processing programs can help you with this). Errors in the mechanics can leave the impression that the author is not concerned with details and can arouse suspicions that the investigator may have been less than thorough in the investigation.

All of the digital forensic frameworks that we discussed in previous chapters have a way to generate a report of findings. We’ll use an early demo version of AccessData’s Forensic Toolkit (FTK) and Technology Pathways’s ProDiscover Basic as examples.

ProDiscover Basic’s reporting capabilities are very easy to use. The generated report includes all items marked as items of interest, along with any case metadata provided by the investigator. Output formats are text and RTF (Rich Text Format): RTF-formatted files can be incorporated into Microsoft Word or other word processors for additional commentary, or as a separate section of a longer report. Figure 12-2 lists the first page of a report on the Greg Schardt case.

AccessData’s FTK provides the investigator with a report wizard that supports tailoring of a report. Information in the report includes both the investigator and the forensics investigator (assuming they are different individuals). Additional dialog boxes ask the examiner what categories of information should be included and what attributes of that information should be included. Figure 12-3 illustrates the evidence section of a report on the Greg Schardt case and clearly shows how the evidence includes both partitioned (NTFS) and unpartitioned space.

Figure 12-3 Evidence section of an FTK report

FTK also allows the investigator to include the case log file that records each action taken by the investigator. Figure 12-4 shows a portion of the log when the report was generated. Although not intended for the body of a report (trust me, it’s rather dry reading), providing the case log as an appendix would clearly demonstrate the actions of the investigator, and the log also serves as a reminder to the investigator as to exactly when and what was done.

Figure 12-4 FTK case log output

From a professional and ethical standpoint, a DFI is required to abide by a set of guidelines. The American Society of Digital Forensics and Electronic Discovery (ASD-FED) provides a code of ethics for its members (www.asdfed.com/domain3).19 Since ASDFED is more closely focused on the forensic examiner, they provide specific guidelines.

These criteria echo several themes that we’ve addressed earlier in this chapter: maintaining objectivity, presenting all facts to the client, avoiding conflict of interest, and so on. I find one of these admonitions very striking: Never knowingly undertake an assignment beyond your ability. A famous line from “Dirty Harry” Callahan (Clint Eastwood in the film Magnum Force) is “A man’s got to know his limitations.” Although it may be extremely difficult to turn down a high-paying and highly interesting case, acting ethically can contribute to convicting the guilty and exonerating the innocent—as well as bringing justice to the victims.

After the investigation is complete, you’ve written the report, and you have provided testimony, you should find a time to reflect on the “lessons learned” from the case, either by yourself or with other colleagues if you’re discussing tools and techniques of the investigation itself. In this instance, you might want to discuss some of the following.

• What improvements can you make in your investigation regarding the gathering of evidence and its analysis?

• Were there particular devices where it was difficult to actually obtain the digital data?

• Are new tools available to increase the speed and accuracy in obtaining the data?

• Are there other sources of corroborating evidence that you discovered, such as logs on remote devices or information stored within the seized evidence (such as new registry fields)?

A second topic for reflection is communicating your results, either via a report or as a witness. Would a different set of topics be more persuasive? Is there corroborating evidence that would make it easier to support a particular interpretation of events? Were there aspects of the presentation that confused your audience?

The ultimate goal of the “lessons learned” exercise is to make you more effective as an investigator. What could you have done differently? How could you have been more efficient (time = money)? How does your new knowledge contribute to preparing and conducting a future investigation? What skills do you need to acquire, and what new tools are available? Did opposing counsel ask questions that you couldn’t answer? And so on.

Digital technologies are ever changing and ever increasing. As a DFI, you need to keep current with these technologies, as well as with the laws that affect the collection of digital evidence. Your adversaries are certainly willing and able to take advantage of any changes that would improve their abilities to carry out their (illegal) activities. Standing still is effectively moving backward.

A DFI can be called as a testimonial or evidentiary witness, in which case their role is to recite the facts of the case regarding access to digital evidence and the results of their analysis. If called as an expert witness, their role is considerably expanded, and they will be able to present conclusions based on the evidence presented and on their own analysis and expertise. Two cases govern when expert witness testimony can be used: Frye and Daubert. Frye presented guidance that is more generic, while Daubert provided a checklist to determine if this testimony can be introduced.

Expert witnesses are required to present details of publications for the last ten years, cases in which they’ve testified/been deposed in the preceding four years, and any previous compensation they have received for testifying. Expert witnesses are also required to prepare and deliver reports. These reports can be formal or informal, verbal or written.

A DFI may testify in court at a trial, at a preliminary hearing, at a deposition, or at a testimony preservation deposition. Regardless of the situation, you should always maintain your composure, stick to the facts of the case, and behave and respond professionally—which may often mean maintaining a professional distance from all other persons involved with the case except for your client.

One measure of a good report is that it is effective in supporting the goals of the investigation and presenting the evidence in a compelling fashion. A good report will create a narrative where the reader or listener will be lead through the evidence discovered and its relevance in supporting the investigation. Conclusions must be supported by the evidence presented. A good report will include only the relevant facts and analysis results in a neutral manner without bias or personal opinion.

Make time after the case is closed (either after your investigation is complete or you have testified) to list the “lessons learned” from the case, whether it be new skills to acquire, new procedures to follow, or different ways of presenting to an audience.

1. How does an investigative report differ from a threshold report? Choose all that apply.

A. An investigative report will include all avenues of investigation, including those that led nowhere.

B. An investigative report contains more details.

C. An investigative report will include details on victimology.

D. An investigative report isn’t subject to discovery.

2. Which statements illustrate the differences between an expert witness and a technical witness? Choose all that apply.

A. Expert witnesses can offer an opinion regarding the evidence.

B. Technical witnesses will usually have been personally involved in the case.

C. Technical witnesses must always write a report for the court.

D. Technical witnesses always speak to the nature of the evidence and how it was obtained.

3. A testimony preservation deposition occurs when (choose all that apply):

A. A witness is not able to be deposed in person

B. The witness’s testimony needs to be preserved

C. An expert witness may not be able to appear in person at the trial

D. Testimony requires facilities only available in a particular laboratory environment

4. The National Institute of Standards’ (NIST’s) efforts to verify the output of various forensics software attempt to address which aspect of the Daubert ruling? Choose all that apply.

A. If the technique has been subject to peer review and publication

B. Whether the technique or theory can or has been tested

C. The known or potential error rate of the technique or theory

D. The existence of standards and controls

5. Which federal statute speaks to stating an opinion on the facts even if the facts are not admissible as testimony?

A. FRE 705

B. FRE 702

C. FRCP 26

D. FRCP 28

6. What should a CV not include?

A. Specific accomplishments

B. Justification for a particular trial

C. Professional education

D. Professional associations

7. Which critical case resulted in a checklist of qualifications that must be met in order for expert witness testimony to be included?

A. Frye

B. Daubert

C. Locard

D. Kumho

8. An expert witness needs to list the cases where they’ve been called to testify going back at least ______ years.

A. Seven

B. Ten

C. Four

D. Three

9. Diagrams, photographs, tables, and so forth should be ____________.

A. Placed in an appendix

B. Interspersed throughout the report

C. Included in a separate volume entirely

D. Preserved from submission if requested by the court

10. What is considered the most important aspect of an investigative report?

A. Organization

B. Narrative

C. Consistency

D. Coverage

1. B. An investigative report will contain more details than a threshold report.

2. A, B, C. All these statements are true. Technical witnesses are not required to write a report.

3. A, B, C, D. All these statements are true.

4. B, C. NIST tests forensics software to determine if it can detect known issues, thereby killing two birds with one stone.

5. A. FRE 705 indicates that expert opinion on the facts is admissible even if the evidence isn’t.

6. B. A CV should not list the trials at which you’ve appeared as a witness.

7. B. Daubert is the case where a checklist for expert testimony was first formulated.

8. C. An expert witness needs to list all cases at which they testified in the last four years.

9. A. Any demonstrative evidence such as photographs, drawings, maps, and so forth should be in an appendix of the report.

10. C. Consistency is the most important element of a report.

1. Casey, E. et al., Digital Evidence and Computer Crime, 3rd ed. (MA: Elsevier, 2011), pp. 273ff.

2. Casey, p. 273.

3. Casey, p. 266.

4. Retrieved from http://www.daubertontheweb.com/frye_opinion.htm.

5. “Rule 702: Testimony by an Expert Witness.” Retrieved from http://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/rule_702.

6. “Rule 705: Disclosing the Fact or Data Underlying an Expert.” Retrieved from www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/rule_705.

7. Nelson, W. et al., Guide to Computer Forensics and Investigations, 4th ed. (MA: Cengage Learning, 2011), p. 544.

8. Nelson, p. 517.

9. Nelson, p. 576.

10. Retrieved from www.eccouncil.org/Support/code-of-ethics.

11. Nelson, W. et al., Guide to Computer Forensics and Investigations, 4th (MA: Cengage, 2010), p. 552.

12. Pirsig, R., Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (NY: William Morrow, 1974), frontispiece.

13. “Rule 26: Duty to Disclose; General Provisions Concerning Discovery.” Retrieved from www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frcp/Rule26.htm.

14. EC-Council. Computer Forensics Investigation Procedures and Responses (NY: Cengage, 2010), p. 6-2.

15. “Spoliation Law & Legal Definition.” Retrieved from definitions.uslegal.com/s/spoliation/.

16. EC-Council, p. 6-5.

17. Ibid.

18. EC-Council, p. 6:128.

19. “Domain: Ethics and Code of Conduct.” Retrieved from www.asdfed.com/domain3.